Abstract

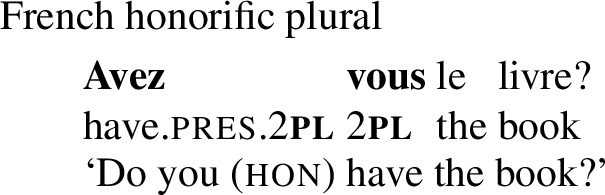

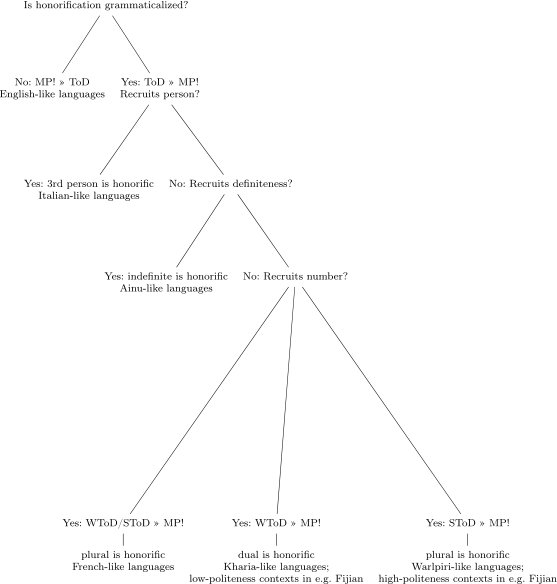

Honorifics are grammaticalized reflexes of politeness, often recruiting existing featural values (e.g. French recruits plural vous for polite address, and German, third person plural Sie). This paper aims to derive their cross-linguistic distribution and interpretation without [hon], an analytical feature present since Corbett (2000). The striking generalization that emerges from a cross-linguistic survey of 120 languages is that only certain featural values are ever recruited for honorification: plural, third person, and indefinite. I show that these values are precisely those which are semantically unmarked, or presuppositionless, allowing the speaker to consider an interlocutor’s negative face (Brown and Levinson 1978). I propose an alternative analysis based on the interaction between semantic markedness, an avoidance-based pragmatic maxim called the Taboo of Directness, and Maximize Presupposition! (Heim 1991) to derive honorific meaning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

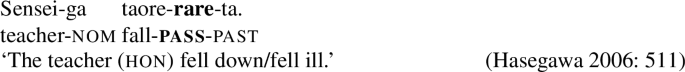

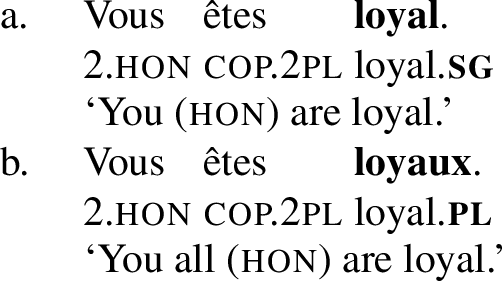

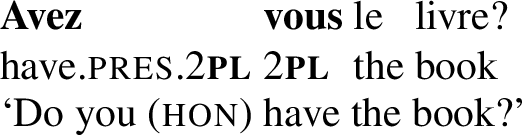

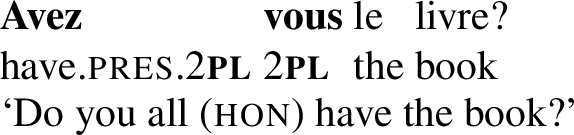

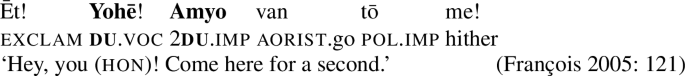

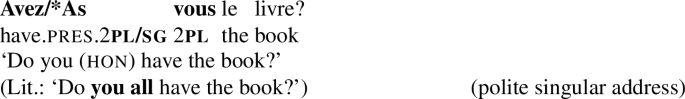

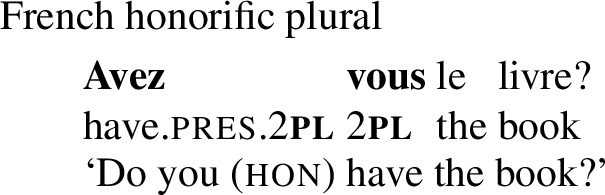

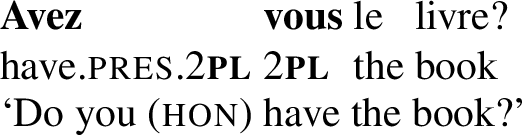

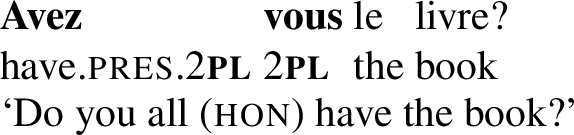

Honorifics are grammaticalized reflexes of politeness, a phenomenon present in many languages of the world. This can be illustrated with French. For one addressee, speakers use the singular pronoun tu for plain address (1) but the plural pronoun vous for polite address (2). (2) also shows that this is grammaticalized, as this usage of the plural for politeness obligatorily triggers corresponding plural verbal agreement.Footnote 1

-

(1)

-

(2)

Here, honorific vous triggers a number mismatch: even though vous is grammatically plural, it is referentially singular. We will see that honorifics display mismatches between a pronoun’s grammatical value and its referential value (this is often the means by which they are detectable). However, the expression of honorification is not limited to plural, as honorifics assume various guises in other languages.

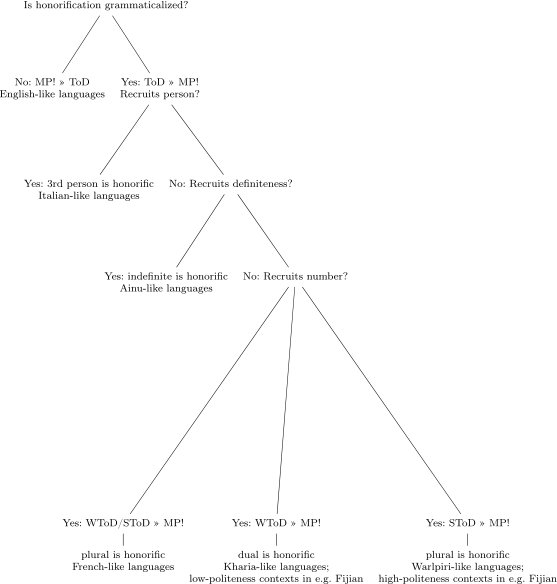

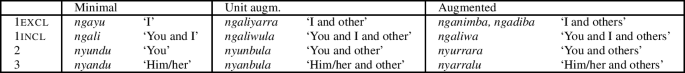

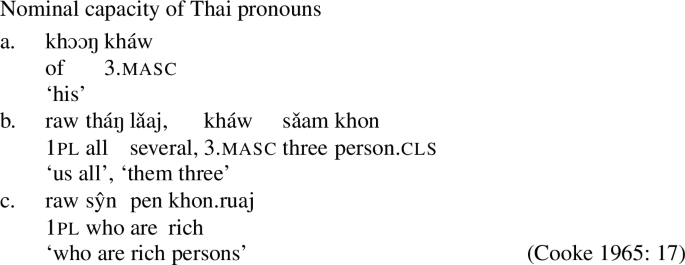

Section 2 illustrates mismatches in the categories of number, person, and definiteness across 90 languages. The main empirical contribution of this paper is the following. While honorifics have diverse manifestations, this diversity is neither random nor unconstrained. Languages have the choice between multiple grammatical categories, but only certain values within these categories are recruited for honorification: honorification systems are constrained to the profiles given in Table 1.

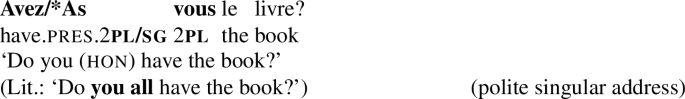

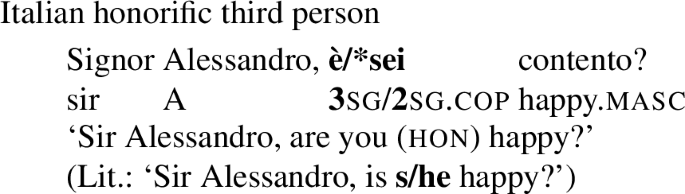

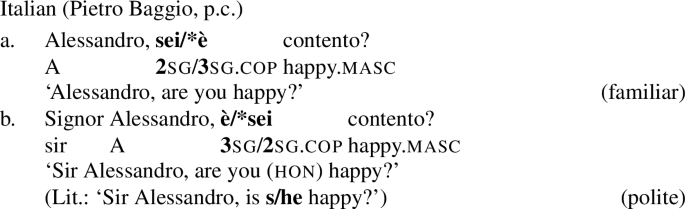

Thus, French is a language which recruits its number opposition for honorification: singular is used for familiar address (1), while plural is used for polite address (2). Languages like Italian recruit its person opposition: second person is used for familiar address (3a), but third person is used for polite address (3b). This is seen from person agreement on the verb, which requires third person agreement in the polite case, creating a person mismatch.

-

(3)

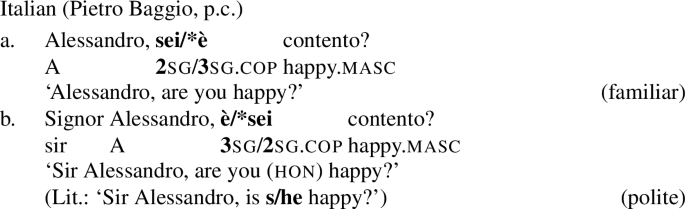

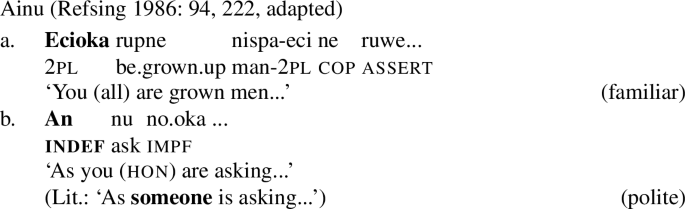

Languages like Ainu, on the other hand, recruit a definiteness opposition. Pronouns (necessarily definite elements) such as 2pl ecioka are used for familiar address (4a), but the indefinite pronoun an is used for polite address (4b).

-

(4)

The generalization that emerges is that languages widely recruit plural number, 3rd person, and indefinites for honorification, but never recruit singular number, first/second person, and definites for the same purposes.

I explain this generalization by observing that attested honorifics are precisely those grammatical values which are the semantically unmarked elements within their categories. Here, semantically unmarked elements are definitionally equivalent to presuppositionally weak elements, a property that allows them to be used in a wider range of contexts. When a speaker favors a semantically unmarked element over a semantically marked one, this avoidance of specificity creates a vagueness as to the speaker’s intended meaning. The preference of semantically unmarked (and hence vague) values is due to a social taboo, the Taboo of Directness (ToD), which militates against direct address/reference in all contexts requiring respect. The overall effect is that of social distancing, an effect that lies at “the heart of respect behavior” (Brown and Levinson 1978: 129).

The ToD proposal is extended to domains of politeness beyond respectful address in later sections—covering honorific reference, politeness in languages with articulated number systems (i.e. systems additionally containing dual and/or paucal), avoidance registers, and polite imperatives. This augments the number of total languages under consideration to 120. Each politeness phenomenon is supplemented with a table of languages exhibiting it, so that the phenomenon itself is illustrated along with its typological robustness.

Crucially, contra previous research, stipulations specific to the phenomenon of honorification, such as [hon], are unnecessary in this account. The cross-linguistic distribution and interpretation of honorifics are explained with existing concepts. This is the main desideratum of this account: extra grammatical machinery need not be utilized even though social meaning is, intuitively, extra-grammatical.

1.1 Delimiting empirical scope

Before the data is laid out, two delimitations are made regarding empirical scope. This paper focuses on the use of existing morphosyntactic features to encode politeness, that is, reappropriations of number and person. This is to be distinguished from politeness phenomena such as allocutive agreement and differentiated speech registers, which I merely outline here.

Firstly, politeness has several grammatical reflexes. Politeness can also take the form of “allocutive agreement,” clause-final agreement markers which signal politeness exclusively geared towards addressees. In Japanese, -masu signals politeness towards the addressee, and has been analyzed by Miyagawa (2017) as agreement at C.

-

(5)

In Souletin Basque (Oyharçabal 1993), politeness is not the only social factor indexed by allocutive agreement; the sex of the addressee may be encoded via the same means. While -ü- encodes politeness towards an addressee of either sex, -k- is used for addressing a male colloquially and -n- a female colloquially. Allocutive agreement is also found in a handful of other languages, including Jingpo (Myanmar, Tibeto-Burman; Zu 2013), Tamil (India/Sri Lanka, Dravidian; McFadden 2017), and Magahi (India, Indo-Aryan; Deepak and Baker 2018).

Allocutivity is set aside here because it is markedly different from honorific pronouns in the following ways. Allocutivity originates very high in the clause (as in Japanese (5)), while the polite pronouns can originate as low as within VPs (in simple clauses like French (2)). Morphologically, there is no phi-featural recruitment involved in allocutivity; allocutive markers are always specialized markers. Lastly, allocutive markers may additionally mark the addressee’s gender (as in Souletin Basque above), while honorific pronouns never make a gender distinction. Several scholars have acknowledged these differences, terming the two types of addressee-related phenomena utterance- vs. content-oriented markers of politeness (Portner et al. 2019), or referent vs. addressee honorifics (Comrie 1976), for example.

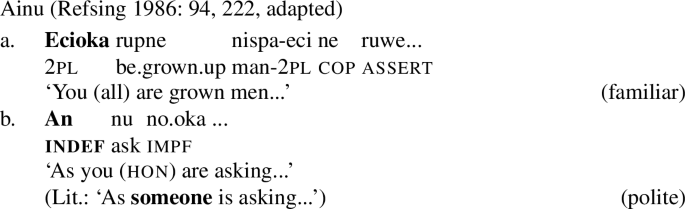

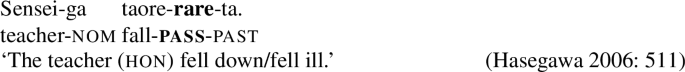

Returning to Japanese, allocutive agreement (which directs politeness towards addressees) exists in parallel with a system of referent honorification (which directs politeness towards referents). In Japanese, politeness can be signaled towards a subject referent via addition of the passive morpheme -(r)are to the verbal complex, as in (6).Footnote 2

-

(6)

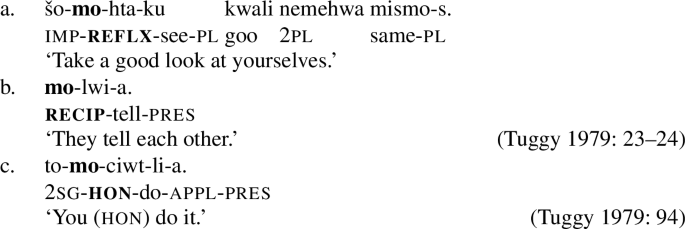

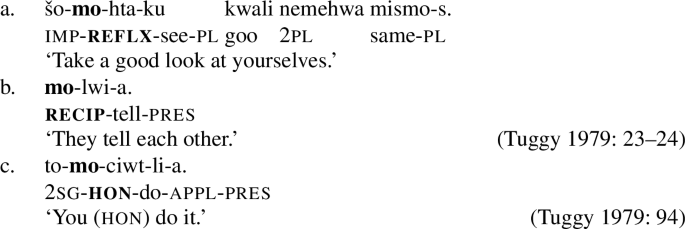

Other functional morphemes can also be recruited to signal politeness; for example, in Tetelcingo Nahuatl, mo- normally marks reflexivity (7a) or reciprocality (7b), but can also be recruited for honorification (7c).

-

(7)

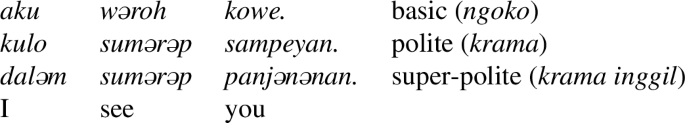

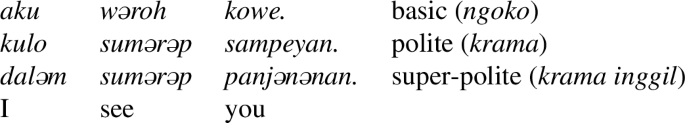

Politeness may also have lexical reflexes, which are found in languages with speech levels. Javanese distinguishes basic (ngoko), polite (krama), and super-polite (krama inggil) speech styles, with an intermediate style (madya). The forms of pronouns and certain predicates differ across speech styles. This is illustrated with variants of the sentence ‘I see you,’ which are truth-conditionally equivalent but not socially so (Suharno 1982: 113, adapted):

-

(8)

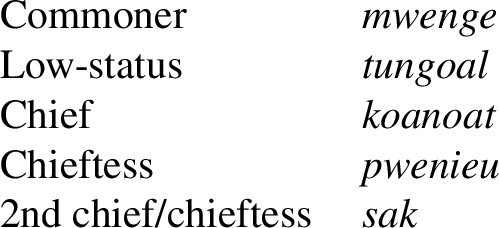

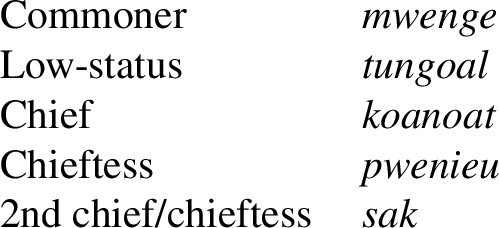

In the honorific register of Pohnpeian (Oceanic), certain predicates differ lexically depending on the social status of the addressee. This is shown for ‘to eat’ below (Keating and Duranti 2006: 151):

-

(9)

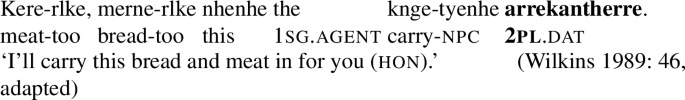

Moreover, the socio-cultural conditions governing the use of honorifics is highly variable. In most European languages, the honorific form is used towards individuals of higher social standing and/or non-intimates. In other languages, the use of honorifics may be additionally governed by factors such as age (e.g. in Korean, Acehnese), caste (e.g. in South India), discourse context (whether the conversation takes place in a casual, formal, or ceremonial setting), familiarity (e.g. in Polish), and kinship relations (e.g. in Aboriginal Australia). Hence, while speakers of French direct honorifics towards persons of higher social standing and non-intimates, speakers of Guugu Yimidhirr, for example, only do so towards fathers-in-law and brothers-in-law. Alternatively, honorifics may be directed towards situations instead of individuals: speakers of Warlpiri use certain honorifics only in ceremonial contexts (specifically, in initiation ceremonies, where boys are formally initiated into manhood). Moreover, the use of honorifics may be either reciprocal (e.g. in in-law avoidance registers) or non-reciprocal (e.g. in South India). In all cases, though, the absence of an expected honorific is deemed inappropriate or offensive.

With regard to diversity of forms, this paper restricts its empirical scope to morphosyntactic reflexes of politeness, that is, honorific uses of morphosyntactic features like number and person. With regard to the socio-cultural factors conditioning the use of such honorifics, I merely touch upon these aspects; focusing instead on deriving the formal representation and interpretation of honorifics.

Section 2 presents novel cross-linguistic data from my typology of honorific pronouns, showing that plural, third person, and indefinite pronouns are widely recruited for honorification; conversely, singular, first/second person, and definite pronouns are never recruited. Section 3 briefly reviews previous analyses based on [hon] and highlights some inadequacies. Section 4 proposes an alternative analysis based on the interaction between semantic markedness, an avoidance-based pragmatic maxim called the Taboo of Directness, and Maximize Presupposition!. Honorificity is thus not derived from a [hon] feature, but from a morphopragmatic algorithm. Section 5 extends the basic proposal beyond singular-plural number systems to articulated number systems further using dual and/or paucal for honorification. Section 6 highlights open challenges and avenues of future work. Section 7 concludes and outlines a new research agenda.

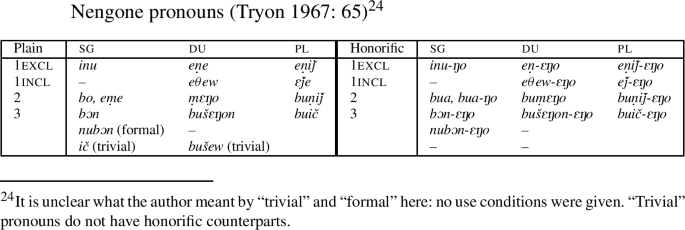

2 The typological picture

This section presents a typology of morphosyntactic honorification strategies in the pronominal domain, totaling 90 languages from >35 genera. The honorific uses of number, person, and definiteness will be illustrated in turn. It was mainly informed by descriptive grammars, typological overviews, and anthropological studies; native speakers were consulted whenever possible.

The main empirical contribution of this typology is as follows: the expression of honorification does not have dedicated exponents, but recruits certain values of existing grammatical categories in these languages. Only plural number, third person, and indefinites may be recruited for honorification.

The following sections present each strategy in turn: honorific uses of plural, third person, and indefiniteness.

2.1 Honorific uses of number

Recall (2), repeated below as (10), showing that plural number is recruited for honorification in French. For polite address towards a singular addressee, the 2pl pronoun vous is used, creating a mismatch between literal meaning (plural) and conveyed meaning (singular and honorific).

-

(10)

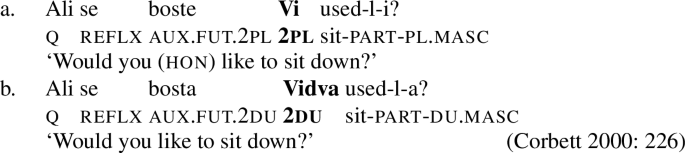

This pattern is well attested for several other European languages, where 2pl pronouns can be used to respectfully address one person. In some cases, the respectful form is capitalized in the orthography. Such pronouns include Lithuanian jūs; Swedish Ni; Russian Vy; Slovenian Vi, Sorbian wy; Czech, Slovak, Bosnian vy; Serbian vi; Italian (southern dialects) voi; Belarusian vei; Ukrainian, Macedonian, Bulgarian vie; and Finnish te.

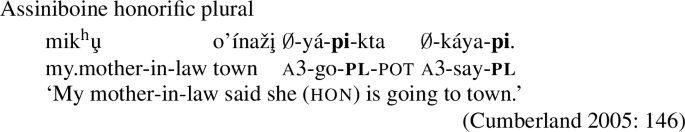

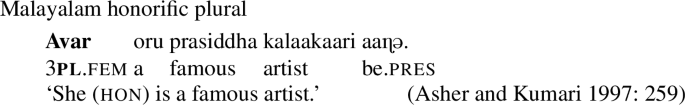

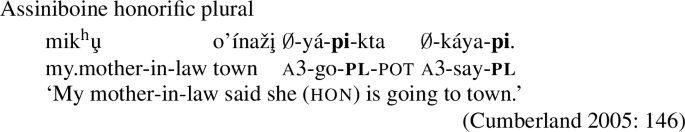

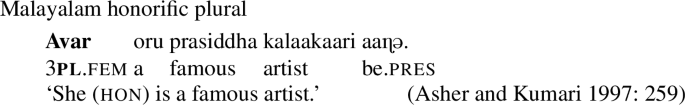

However, honorific plural is not just restricted to Europe. It is in fact a cross-linguistic trend, being the most frequent honorification strategy across the world’s languages, found in geographically and genetically unrelated languages. In Assiniboine (Canada/USA, Siouan), plural is recruited for honorific reference towards in-laws (11); in Malayalam (India, Dravidian), for honorific reference towards respected persons (12); in Koromfé (Burkina Faso, Volta-Congo) for village chiefs (13).

-

(11)

-

(12)

-

(13)

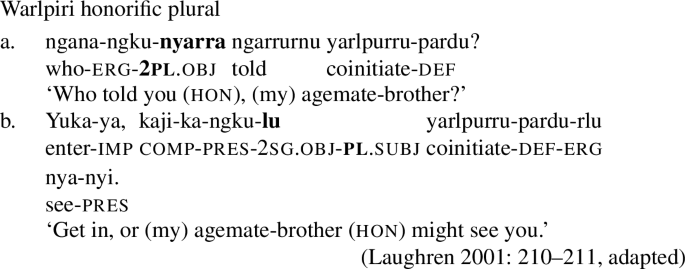

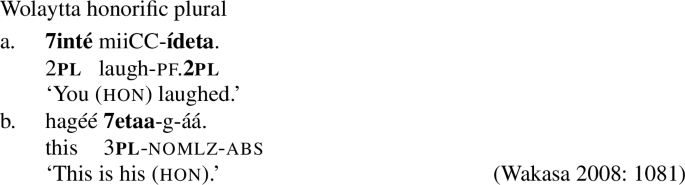

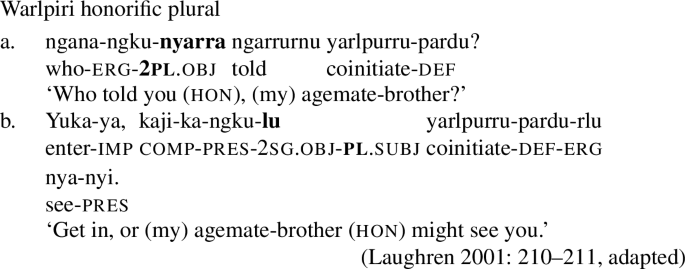

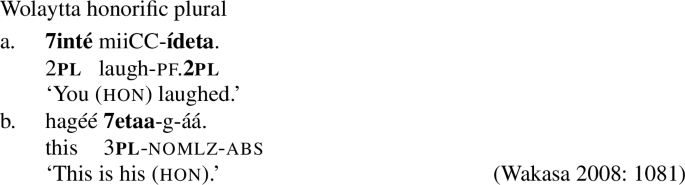

In Warlpiri (Australia, Pama-Nyungan), plural can be recruited for either honorific address (14a) or honorific reference (14b) towards coinitiates. The same pertains for Wolaytta (Ethiopia, Omotic), where plural is used for honorific address (15)[a] or honorific reference (15)[b].

-

(14)

-

(15)

Table 2 shows that honorific plural is very well represented, robustly present in a geographically and genetically diverse group of languages. Thus, the honorific use of plural is by no means an isolated accident, but a typological trend.

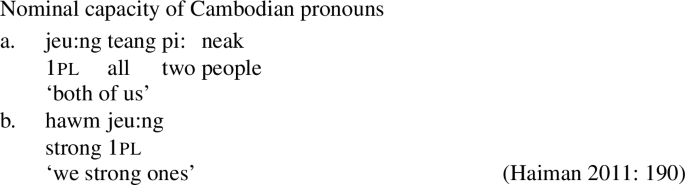

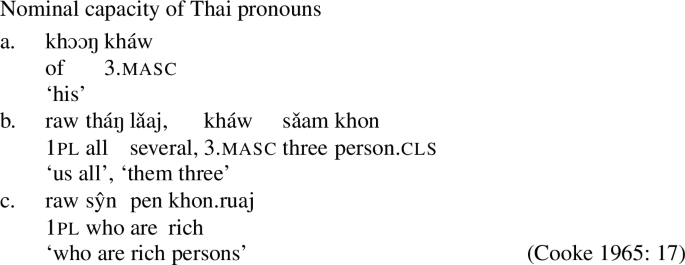

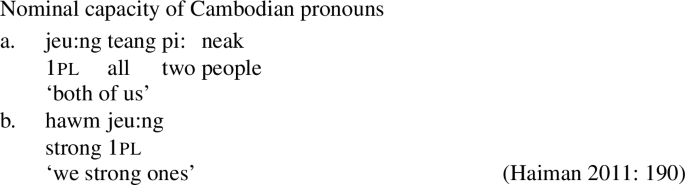

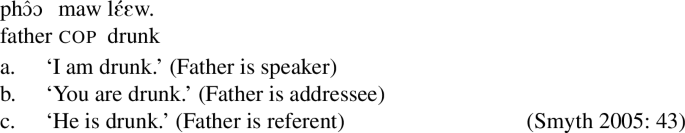

Languages differ on whether honorific plural may be used for self-address, address, and/or reference. Tinrin allows honorific plural for singular address, but not honorific reference. Indian languages such as Kashmiri (Koul and Wali 2006: 51), Kannada (Schiffman 1983: 38), and Malayalam (Asher and Kumari 1997) allow for both. In some languages, the plural of majesty is used for honorific self-reference (cf. “royal we” in English). This is also found in Thai, for example, where the first person plural pronoun jeu:ng can only be used by royalty for self-reference.

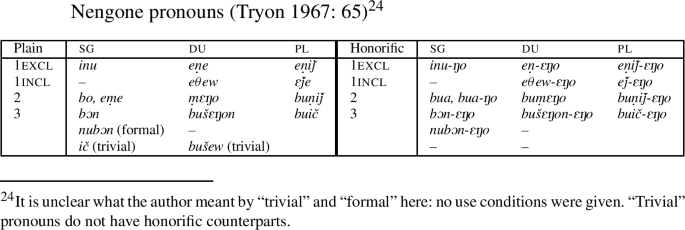

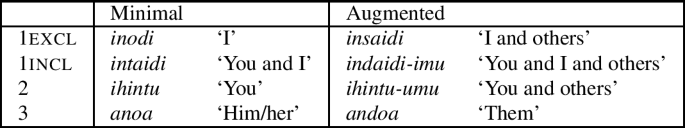

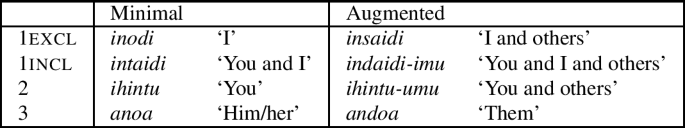

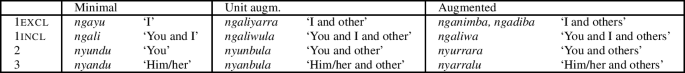

The diacritics on several languages in Table 2 mark number systems aside from singular-plural: number systems can be more articulated, with multiple nonsingulars such as dual (for ‘two’) and paucal (for ‘a few’). * indicates that the language has a singular-dual-plural system, ** a singular-dual-paucal-plural system, *** a singular-dual-paucal-greater paucal-plural system, + a minimal-augmented system, and ++ a minimal-unit augmented-augmented system.Footnote 3

Recent work in number theory captures the diversity of number systems with different featural representations for each number system (since Hale 1973; Silverstein 1976; Noyer 1992; more recently Harbour 2014). If this line of thinking is on the right track, then Table 2 also shows the featural diversity of honorific plural: the “plurals” that are put to honorific uses do not stem from identical formal origins. Since these plurals are featurally distinct, this suggests that the phenomenon of honorific plural is not dependent on how a particular language’s number system is formally derived.

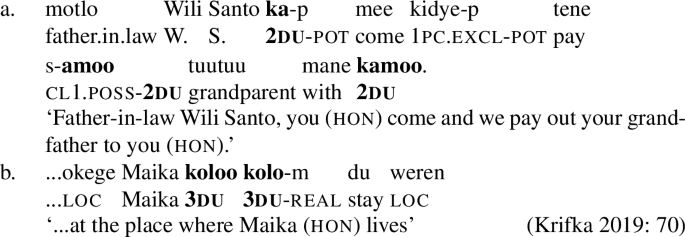

So far, we have seen that the familiar-polite opposition is encoded with the singular-plural opposition. However, further-refined honorification systems can be encoded in systems with more grammatical numbers. This is the case in many Oceanic languages, which have a dual if not a paucal as well.

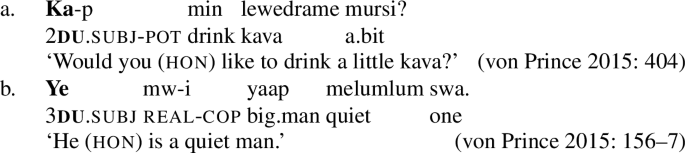

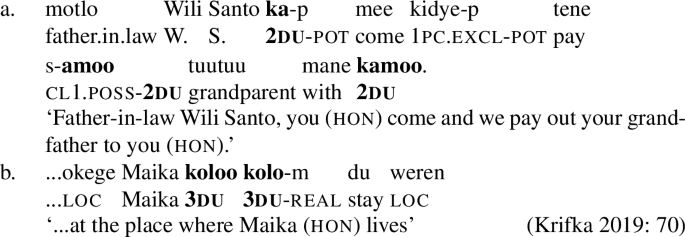

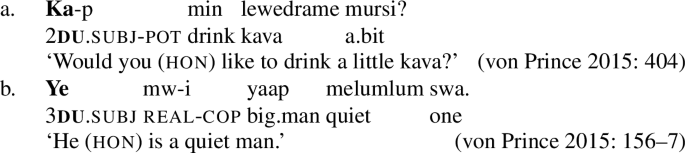

In Daakaka (Vanuatu, Oceanic), dual is used for polite address or reference, skipping plural for honorification. In (16a), polite address towards a single in-law shows 2du ka being used instead of 2sg ko. In (16b), polite reference towards a single respected person shows 3du ye instead of 3sg ∅; note also the mismatch with the numeral swa ‘one.’

-

(16)

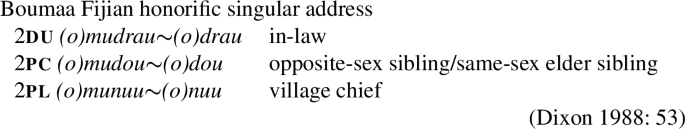

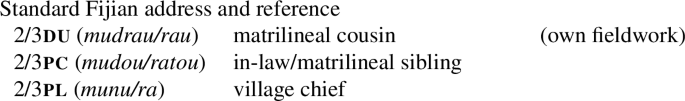

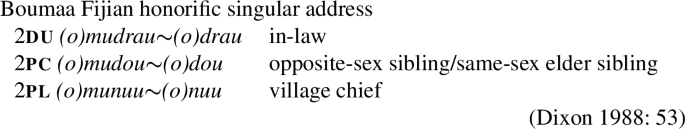

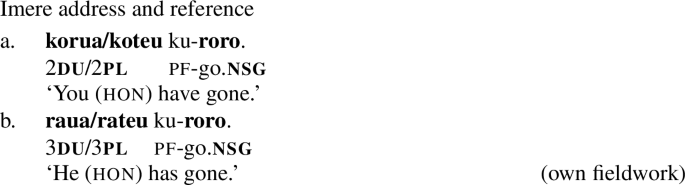

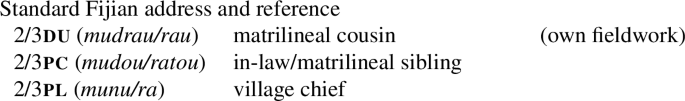

There are also honorification systems which use all nonsingulars for honorification. In Boumaa Fijian (Fiji, Oceanic) (17), the use of higher grammatical numbers is accompanied by an escalating cline in the social hierarchy. In ascending social rank, the respected persons in Fijian society are in-laws, matrilineal kin, and the village chief. The lowest nonsingular, dual, can be used for the address or reference of an in-law, but the highest nonsingular, plural, is exclusively reserved for the village chief.

-

(17)

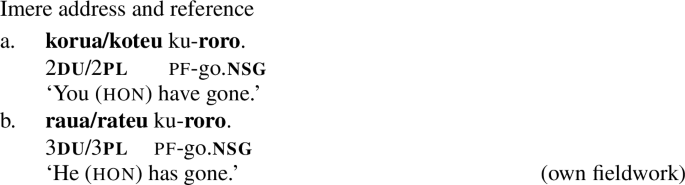

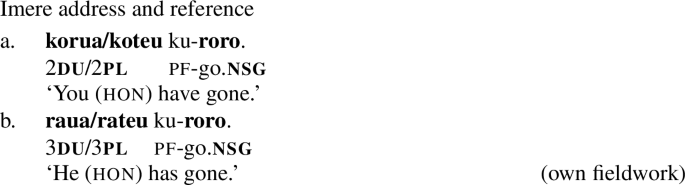

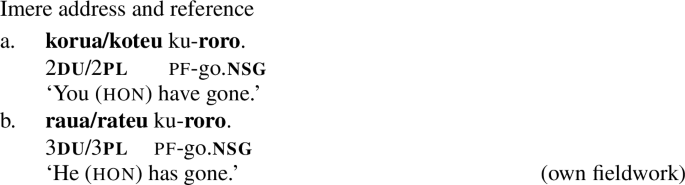

Similarly, either nonsingular can be respectfully used in Imere (Vanuatu, Oceanic), where either dual or plural can be used for respectful address (18a) or respectful reference (18b). This is also shown with the number-suppletive stem ‘go’: only the nonsingular stem roro is grammatical in both examples and the singular stem fano is ungrammatical. No additional honorific meaning is indicated with the use of the plural over the dual.

-

(18)

Such “articulated” honorification systems provide a rich and nuanced source of typological variation, informing the final proposal in important ways. They are the focus of Sect. 5.

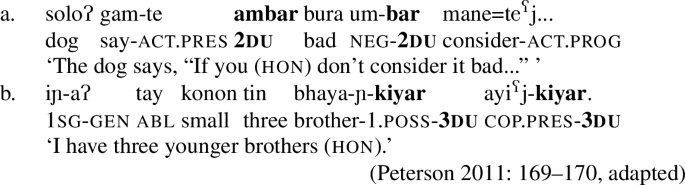

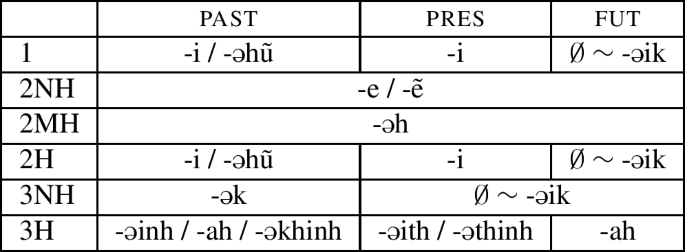

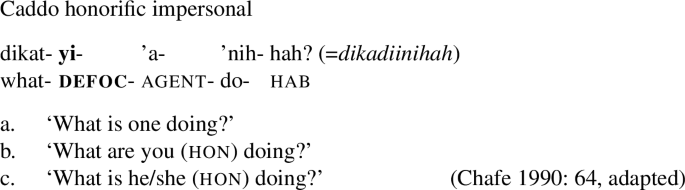

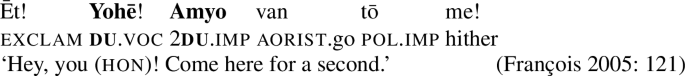

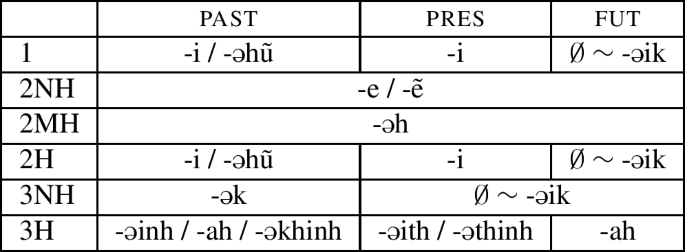

2.2 Honorific uses of person

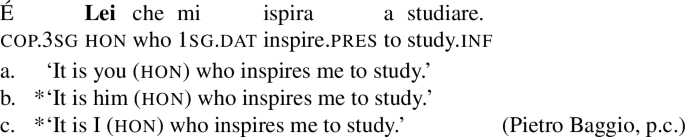

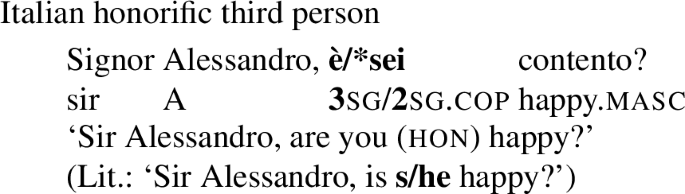

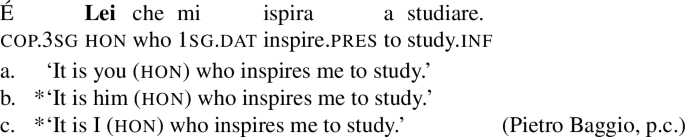

Another grammatical category recruited for honorification is person. Italian, for example, uses third person for honorification, where the verbal agreement is obligatorily 3sg for honorific address. This creates a person mismatch between literal meaning (third person) and conveyed meaning (second person and honorific). This is illustrated in (19).

-

(19)

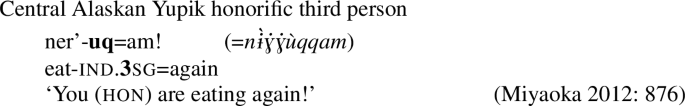

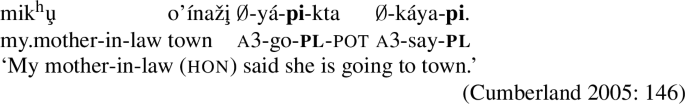

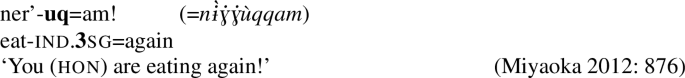

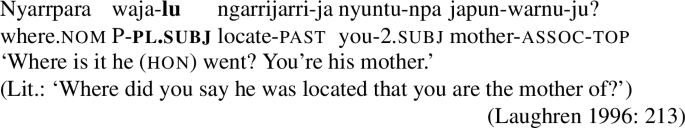

The same pattern is also found in Central Alaskan Yupik (Alaska, Yupik) (20).

-

(20)

The number of languages which use honorific third person are fewer than those which use honorific plural. Nonetheless, the relevant languages do not constitute a geographically or genetically homogeneous group, as Table 3 shows.

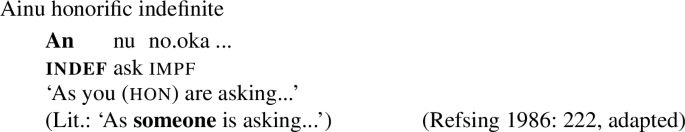

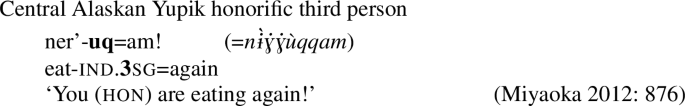

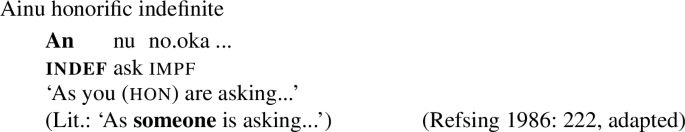

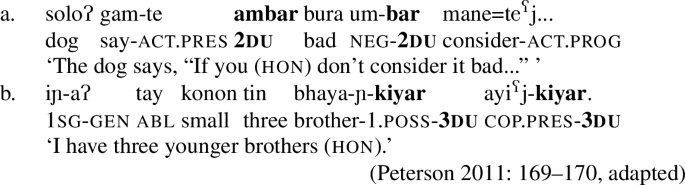

2.3 Honorific uses of indefiniteness

The last type of honorification strategy to be presented here is that of honorific indefiniteness. In this strategy, a specific, respected person is referred to with an indefinite, creating a mismatch between literal meaning (indefinite) and conveyed meaning (definite and honorific). This is illustrated for Ainu (Hokkaido, isolate), where the indefinite pronoun an can be recruited for honorific meaning (21).

-

(21)

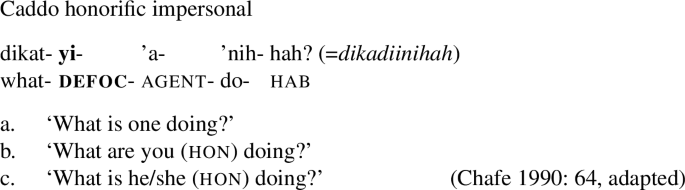

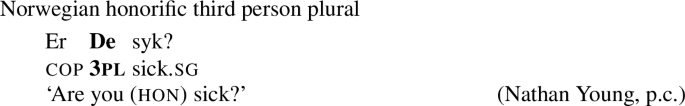

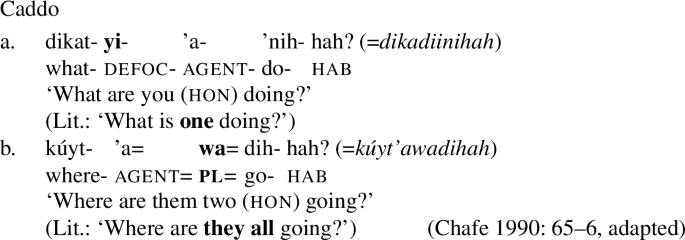

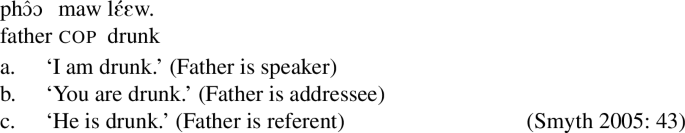

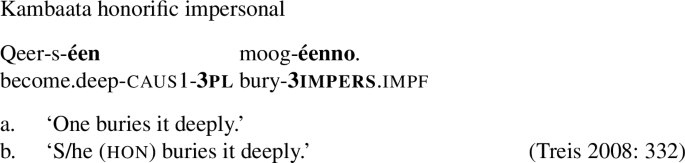

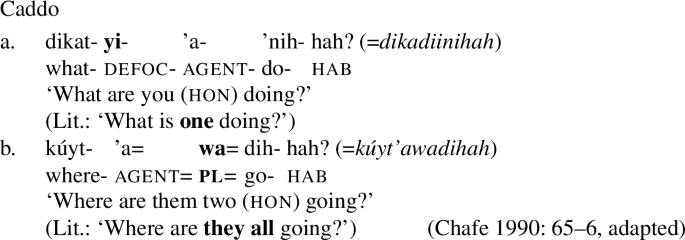

What I am terming honorific “indefiniteness” here also includes instances of honorific uses of impersonals. In Caddo, the “defocusing prefix” may be used towards an impersonal reading (22a). However, such a sentence has two more possible interpretations: honorifying an addressee (22b) or a referent (22c).

-

(22)

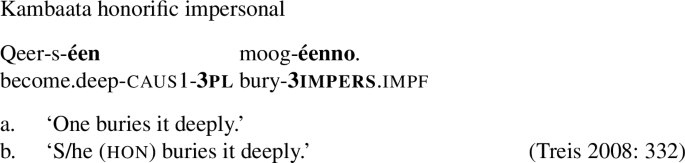

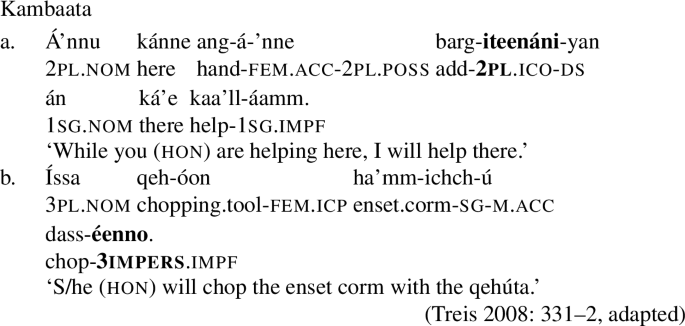

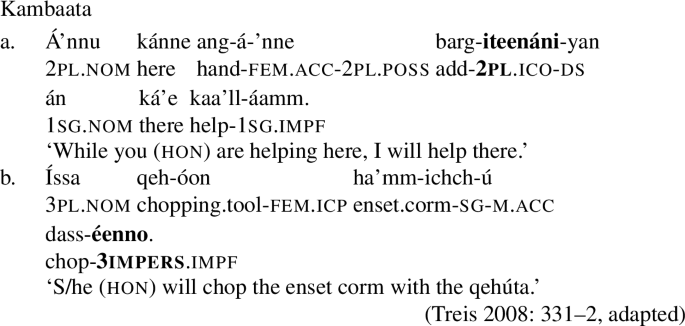

Kambaata exhibits a similar ambiguity. First note that Kambaata has an honorific plural, so that 3pl verbal agreement is used for a respected referent. When this occurs, as in (23) below, then the agreement used for impersonal subjects also appears. The resulting sentence has both impersonal (23a) and honorific (23b) interpretations. (The example below is one with pro-drop, and is thus only compatible with previously mentioned referents.)

-

(23)

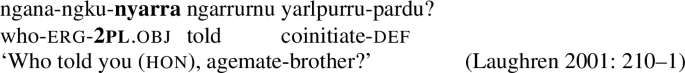

Honorific indefiniteness has also been reported for several Athabaskan languages, where the category of “fourth person” (normally used for generic statements, indefinite referents, and/or absent referents) is recruited for honorification. This is found in Navajo (Goossen 1995: 53, 283), Western Apache (De Reuse and Goode 2006: 348), and Wailaki (Begay 2017: 174). Unfortunately, no examples were provided, and I cannot replicate any for the reader here.

Table 4 summarizes the known uses of honorific indefiniteness found in my survey. It is again notable that these languages are geographically and genetically heterogeneous.

2.4 Combinations across, and within, languages

Cross-linguistic data shows that honorifics do not have their own exponents. Rather, plural, third person, and indefiniteness—grammatical categories which independently have non-honorific meanings—are recruited as honorification strategies in these languages.

Strikingly, we find more elaborated honorific systems which provide further support for the reality of these recruitment patterns. In one type of system, the two strategies of honorific plural and honorific third person are combined. The result is that 3pl pronouns are used for honorific address. In another type of system, more than one strategy is active in tandem for different social contexts requiring honorifics. For example, honorific plural is used for one respected category of persons, but honorific third person is used for another. I will go through each type of system in turn.

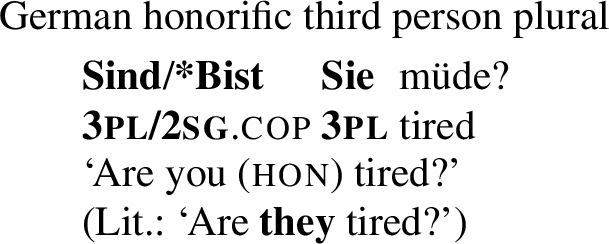

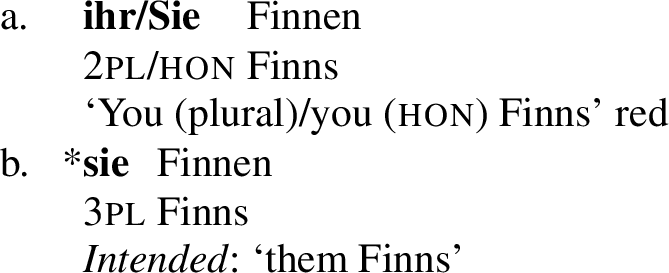

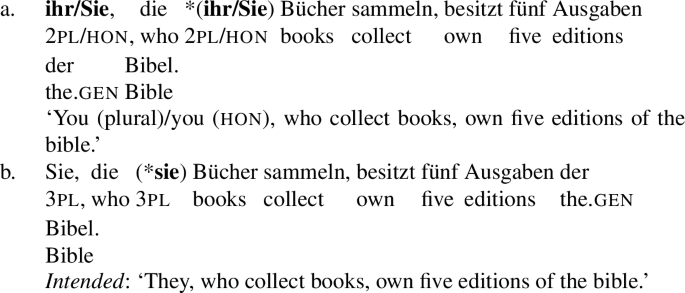

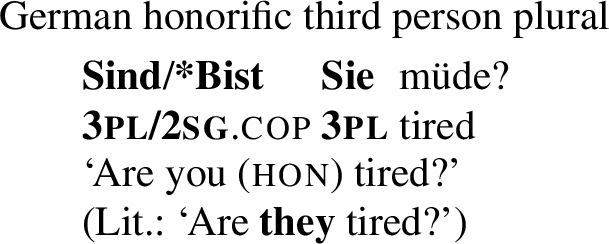

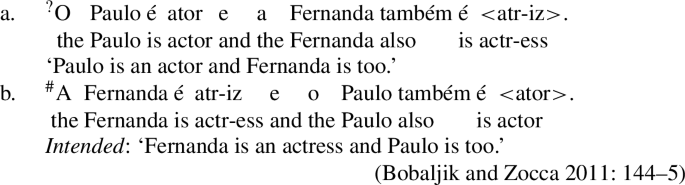

German is a language which combines the two strategies of honorific plural and honorific third person. Its 3pl pronoun Sie is recruited for honorific address, which obligatorily triggers 3pl verbal agreement (24). This creates a person and number mismatch between literal meaning (third person plural) and conveyed meaning (second person singular and honorific).Footnote 4

-

(24)

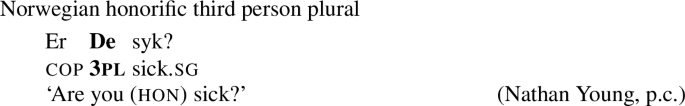

The same pattern is found in Norwegian (Norway, Germanic), where its 3pl pronoun, De, is recruited for honorific address.

-

(25)

In my survey, other instances of honorific third person plural are found in certain dialects of Slovenian (Slovenia, Slavic) and Tagalog (Philippines, Polynesian).

Readers might notice that Tagalog was already listed as a language which uses honorific plural in Table 2. This is because Tagalog uses honorific plural and honorific third person plural in tandem: both are equally available options. Thus, for honorific address, both 2pl kayó and 3pl silá are valid polite substitutions for 2sg ikáw (Schachter and Otanes 1972: 90–91).

Resembling Tagalog in this regard are Slovenian (mainly spoken in Slovenia, Slavic) and Ilocano (Philippines, Polynesian). In Slovenian, the 2pl pronoun Vi is used for honorific singular address, and Priestly (1993: 414–415) notes that 3pl Onikanje is also a valid substitution in some dialects.Footnote 5 In Ilocano, both 2pl dakayo and 3pl isuda can be used for honorific singular address (Rubino 1999: 52), where the 3pl substitution is considered more formal than the 2pl one.

In addition to combining number with person for the purposes of honorification, languages can also combine number with indefiniteness. Exemplifying this is Caddo, where honorific indefiniteness is used for one in-law (26a), but honorific plural is used for two in-laws (26b). The following example illustrates this for honorific reference, but the same pertains for honorific address as well.

-

(26)

Also combining honorific uses of phi-features with indefinites is Kambaata (S. Ethiopia, Afro-Asiatic): it exhibits 2pl verbal agreement for honorific address, but impersonal verbal agreement for honorific reference.

-

(27)

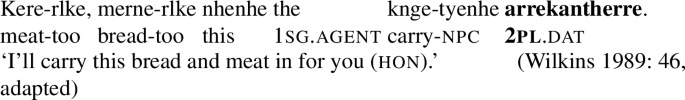

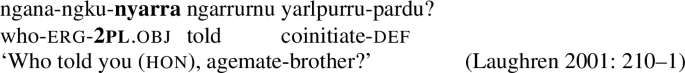

Lastly, languages can also have distinct honorification strategies operating in tandem, each reserved for different interactional contexts. Exemplifying this is Warlpiri (Laughren 2001), where honorific plural and honorific third person are both active. The strategy of honorific third person is used only if the interaction is taking place within a ceremonial context; for example, in initiation rituals, where boys are initiated into manhood. Within such ceremonies, the speaker addresses other participants with a 3sg pronoun. In contrast, the strategy of honorific plural is used for everyday contexts where politeness is required; for example, if the speaker is addressing anyone related by marriage, or anyone who was co-initiated with the speaker.

This concludes the main empirical section of this paper. Many other strategies (such as reflexivization, passivization) also formed small typologies (n<10), but these are not so robustly attested, and are left for future work.Footnote 6

2.5 Generalizations

In the previous sections, we have seen that honorifics may recruit values across a range of categories spanning person, number, and definiteness. Strikingly, certain values within these categories are never recruited for honorification. Hence, languages show considerable diversity in the grammatical features recruited for honorification, but this diversity is constrained and non-arbitrary. Generalizations that emerge from the typology are stated below:

-

(28)

Unattested honorifics

-

a.

Singular is never recruited for honorification.

-

b.

First person and second person are never recruited for honorification.

-

c.

Definites are never recruited for honorification.

-

a.

To appreciate these generalizations, consider the potential empirical profiles of unattested honorification systems.

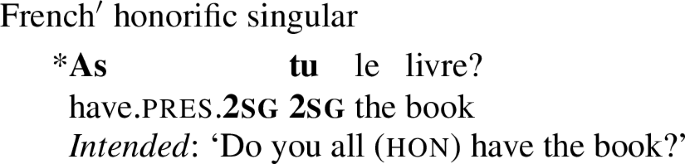

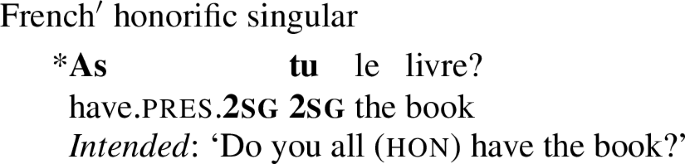

For number, recall that French uses plural vous for honorifying a single addressee (it can also be used to honorify multiple addressees). However, we never find a language French′, where the second singular pronoun is used for doing so, which would resemble (29).

-

(29)

Neither do we find languages where third person singular pronouns are used to honorify multiple referents. Such gaps are captured by (28a): singular is never recruited for honorification.

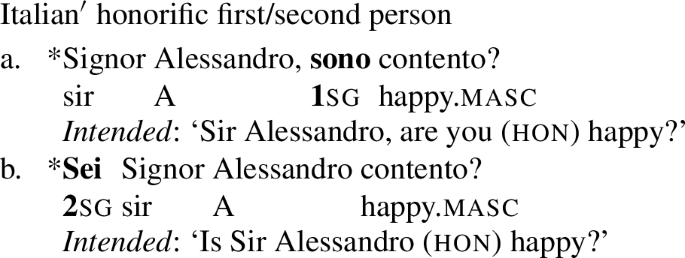

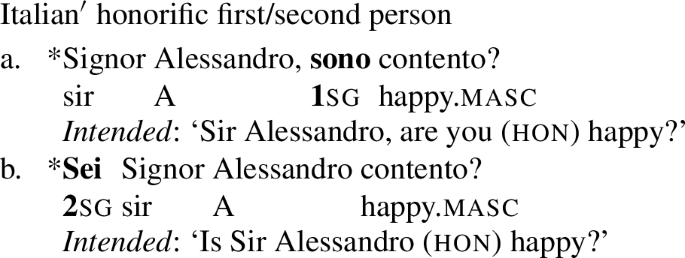

For person, recall that Italian uses third person for honorific address. But we never find a language like Italian′, where first person is used for honorific address, which would look like (30a). Moreover, we never find second person used for honorific reference, which would resemble (30b).

-

(30)

The absence of the patterns in (30) exemplifies (28b): first and second persons are never recruited for honorification.

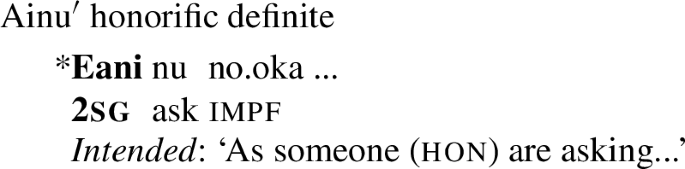

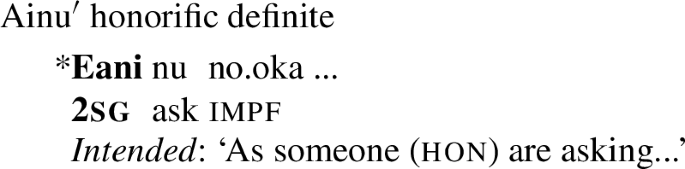

Lastly, for indefiniteness, recall that Ainu uses the indefinite pronoun an for honorific address. But again, never do we find a language like Ainu′, where pronouns (which are necessarily definite) are used to honorify indefinite persons, as in (31).

-

(31)

This is due to (28c): definites are never recruited for honorification.

Even in languages with combinations of distinct honorification strategies, the attested combinations do not deviate from the generalizations in (28). For combinations of honorific plural and third person, recall that German uses 3pl for honorific address. There is no language German′, which uses 1pl or 1sg for doing so which would defy (28a) and (28b). For combinations of honorific plural and indefiniteness, neither is there a language Caddo′, which uses demonstratives to honorify one in-law, and 2sg to honorify two in-laws. This is because definites and singular number are never recruited for honorification, and hence form an illicit combination, which would defy (28a) and (28c).

Rather, the only options in these grammatical domains are honorific uses of nonsingulars (Sect. 2.1), third person (Sect. 2.2), indefiniteness (Sect. 2.3), or combinations of these (Sect. 2.4). Even though other honorification systems are logically possible, they are never attested in these languages. The distribution of honorifics, then, is highly restricted despite the wide range of grammatical categories recruited. This restriction will be the main explicandum of this paper. Section 3 briefly reviews previous proposals. Section 4 works towards a principled analysis of honorifics, arguing that honorifics actually form a natural class, consisting only of elements which are semantically unmarked.

3 Previous analyses

Previous analyses of honorific pronouns typically assume a feature specialized for honorification: for example, Simon (2003) and Ackema and Neeleman (2018) assume [hon] in their representations of honorific pronouns. Macaulay (2015a) takes a similar stance, assuming the feature [status]; with Portner, Pak and Zanuttini (2019) proposing [formal].

Corbett (2012) takes a more cautious approach, considering a [hon] feature only for a handful of languages (some of these are illustrated in Sect. 6.4). Others do not situate their honorific feature in the morphosyntax, but in the expressive dimension within a multidimensional semantics (e.g. Potts 2005; McCready 2019). Non-generativist perspectives (e.g. Listen 1999: 44) use conceptual metaphors such as POWERFUL IS PLURAL to capture honorific uses of plural.

Here, I review two recent proposals in detail: the impoverishment-based proposal of Ackema and Neeleman (2018), and the agreement-based one of Portner, Pak and Zanuttini (2019). Both assume a grammatical feature dedicated to honorification, and are critiqued in light of the typological findings from Sect. 2.

3.1 Ackema and Neeleman (2018): Impoverishment

For Ackema and Neeleman (2018) (henceforth A&N), the grammatical feature [hon] is included in the representation of all honorific pronouns, formally distinguishing plain from honorific pronouns. [hon] is on par with other pronominal features, such as those of number and person. However, [hon] does not affect reference, merely indicating that the members in its set are honorable. (A&N develop their own features for person and number, but their analysis of honorifics is fairly theory-neutral.)

As we have extensively seen, a hallmark of an honorific pronoun is the mismatch it creates. A&N explain such mismatches with impoverishment, where [hon] conditions deletion of the offending feature, either at LF or PF.

Consider how this works for, say, French honorific vous, which exhibits a number mismatch. A&N assume that, whereas plain vous contains features for a second person plural denotation, honorific vous additionally contains a [hon] feature. In honorific contexts, [hon] triggers deletion of the plural feature. This is termed LF impoverishment, which conditions deletion of features after syntax but before interpretation, as in (32).

-

(32)

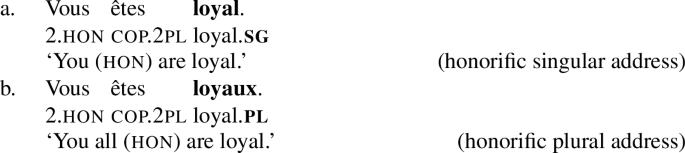

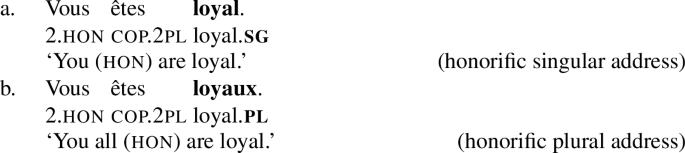

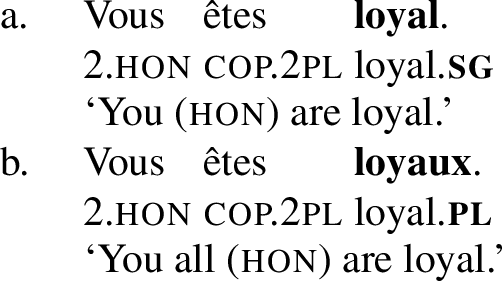

The resulting pronoun is number-neutral, concordant with the interpretation of honorific vous: it can be used respectfully towards one or more addressees. This can be seen from variable number agreement on the adjective. If vous is respectfully directed towards one addressee, adjectival agreement is singular (33a). Towards multiple addressees, adjectival agreement is plural (33b).

-

(33)

This also explains why honorific vous obligatorily triggers plural verbal agreement, as this impoverishment happens at LF, after syntactic agreement has taken place. The variable adjectival agreement is taken to be semantic agreement (see Ackema 2014; also Wechsler 2011 on notional agreement).

Consider further how this would work for German honorific Sie, which creates both number and person mismatches when deployed for honorific address. Whereas plain sie contains features for a third person plural denotation, honorific Sie additionally contains a [hon] feature. In this case, impoverishment takes place at PF. [hon] triggers impoverishment of the feature responsible for a second person interpretation (in their framework, the [prox(imal)] feature) at PF (34a), so the resulting pronoun is phonologically identical to the third person plural pronoun sie. This eliminates the person mismatch. Another dose of impoverishment, this time at LF (34b), derives the desired number-neutrality, eliminating the number mismatch.

-

(34)

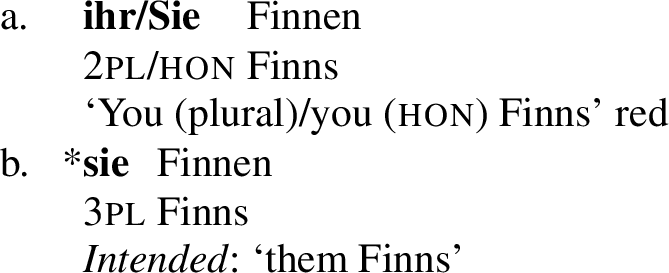

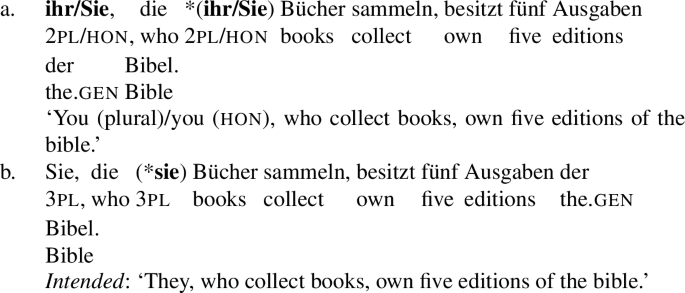

PF impoverishment allows honorific Sie to lead a double life: it is phonologically identical to third person plural, but syntactically identical to a second person plural. This is because PF impoverishment only establishes a surface similarity to 3pl sie: the authors cite Simon (2003) in observing that honorific Sie syntactically behaves like the second person plural pronoun, ihr, rather than the third person plural pronoun, sie. Evidence is given from close appositions (35a–b) and relative clauses (36). In both constructions, the distribution of honorific Sie patterns with that of 2pl ihr, away from that of 3pl sie.

-

(35)

-

(36)

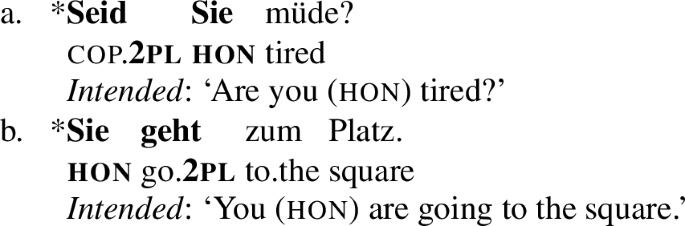

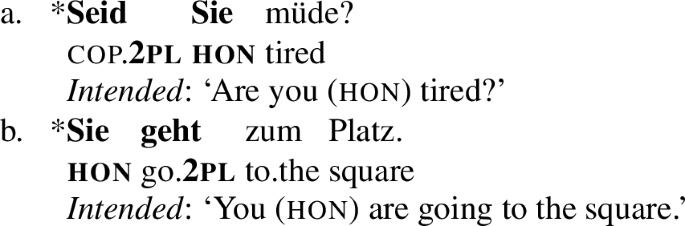

Although, it remains a mystery under A&N’s account as to why honorific Sie is incompatible with second person plural verbal agreement (37).

-

(37)

In sum, A&N’s proposal of recruited honorifics rests on the assumption that [hon]-conditioned impoverishment (at LF or PF) resolves the mismatches that recruited honorifics create.

A&N’s account does have adequate empirical coverage, as it ensures that certain values can never be a target of impoverishment for the following reasons. (It remains a mystery as to why definites are never recruited for honorification (28c), but honorific uses of indefiniteness were not within their empirical scope.) The privative view of number adopted by A&N accounts for (28a) naturally. Plural forms are specified via a pl feature. The absence of a feature has interpretative effects, so that the absence of plural implies singular. Since singular is never specified in syntax, it can never be the target of impoverishment. This explains why singular pronouns are never recruited for honorifics.

As to why first and second persons are never recruited for honorification, A&N give functional explanations. Second person singular pronouns are never recruited for honorific singular address, as the intended respectful effect would not be detectable via a mismatch. Neither are first person singular pronouns, due to learnability considerations: a mismatch is necessary for a pronoun to be interpreted as honorific. But a mismatch is never possible for the first singular, as it is always interpreted as the speaker, making its acquisition as a honorific “difficult if not impossible” (Ackema and Neeleman 2018: 46). Since honorification is definitionally equivalent to grammaticalized social meaning, this social meaning would be difficult to detect if there were no grammatical indications in the form of a mismatch.

However, such explanations are not fully satisfactory. A mismatch would be detectable if second person pronouns were recruited for honorific reference (honoring a third person), but this is unattested. Two further aspects of the proposal are problematic: [hon] is an unusual morphosyntactic feature, having none of the typical properties of its ilk, and the impoverishment approach derives unattested honorification systems. I turn to these below.

3.2 An unusual feature, an unusual operation

By assuming that [hon] triggers impoverishment, A&N is able to account for why mismatches are typical for honorifics. Here, I review the consequences of assuming [hon], and the impoverishment operation it triggers. We start by observing that [hon] is highly unusual as a grammatical feature, patterning away from other well-established features with regard to its phonological and syntactic properties.

Let us first consider phonological properties, comparing [hon] to better-established features such as [pl]. In many languages, plurality has dedicated exponence, whether they are pronominal or nominal markers of plurality. A few examples of pronominal plural markers are Yauyos Quechua -kuna (Shimelman 2017), Tok Pisin -pela (Wurm and Mühlhäusler 1985: 343), Vietnamese chúng, Burmese -tyev (Cooke 1965); examples of nominal plural markers are Vietnamese nhung, Burmese dowq (Cooke 1965).

However, Sect. 2 showed that this is not the case for [hon]; rather, languages extensively recruit existing exponents. Thus, there is little phonological basis for assuming [hon] as a dedicated grammatical feature, if we assume that syntactic features generally have their own exponents.

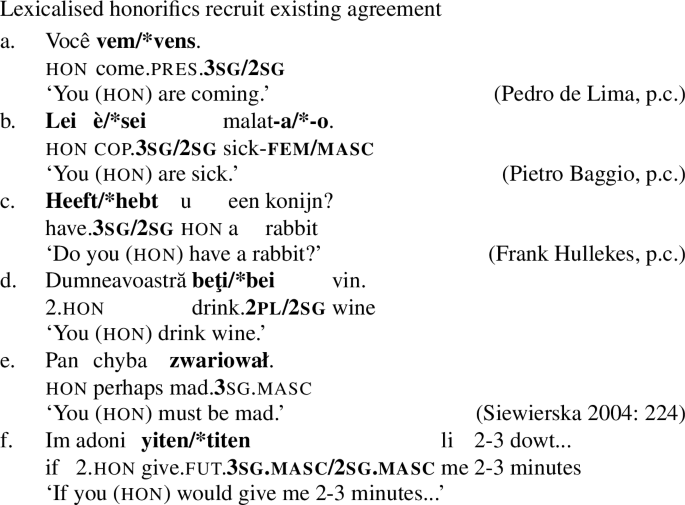

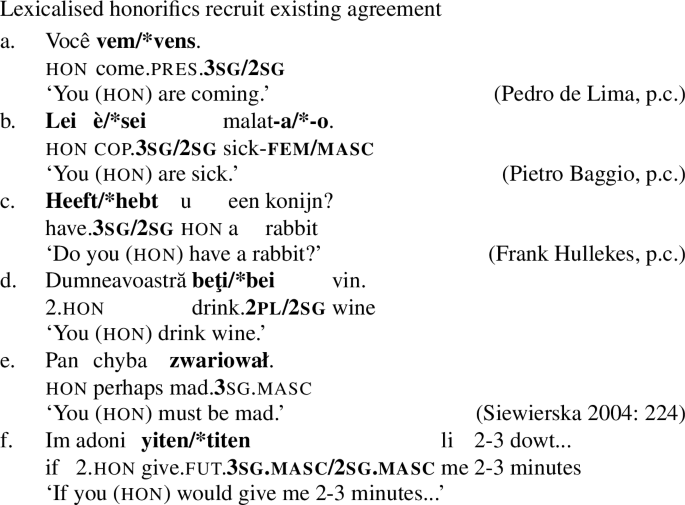

What about languages which do have dedicated exponents for honorification? In many European languages, the pronoun for honorific address is not recruited from any existing part of the pronominal paradigm. Well-known examples include Spanish usted, Portuguese Você, Romanian dumneavoastră, Dutch/Afrikaans u, Polish Pan/Pani. For such pronouns, it seems reasonable to assume that [hon] serves to formally distinguish them from their non-honorific counterparts. Indeed, A&N assume dedicated spell-out rules for these honorifics without making use of impoverishment. Let us call such forms lexicalised honorifics.

Despite the dedicated exponence, dedicated syntactic reflexes are still lacking. Syntactic features usually drive many formal operations (e.g. movement, concord, agreement). For example, [wh] triggers wh-movement. Plural is well-known for having syntactic effects, such as triggering plural concord. Plural number also participates in omnivorous agreement, where one plural marker may cross-reference more than one plural argument (e.g. Nevins 2011), a phenomenon exclusive to singular number.

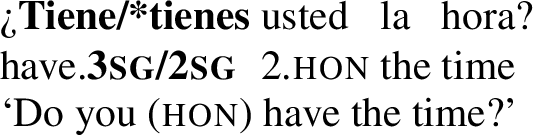

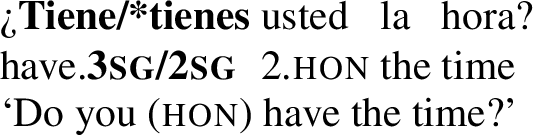

[hon] does not have any of these syntactic repercussions. As far as I know, no language exhibits syntactic movement triggered by the presence of a honorific pronoun. When a language recruits a pronoun for honorification, the language does not display specialized honorific agreement either.Footnote 7 Consider Spanish usted: when used for honorific address, it obligatorily triggers 3sg agreement, creating a now-familiar person mismatch (38). For such pronouns, then, A&N must assume that impoverishment selectively targets verbal agreement, but not the pronoun itself.

-

(38)

However, the lack of dedicated honorific agreement is due to the fact that many European honorific pronouns originate from nominals referring to purported traits or virtues, such as ‘grace,’ ‘lordship,’ or ‘holiness.’ Lexical material is recruited and subsequently grammaticalized. (Since I only mention their diachronic history here, I return to the question of their synchronic representation in Sect. 6.3.) Penny (1991: 125) documents this in detail for Spanish, where the expression Vuestra Merced ‘your mercy’ reduced gradually into the present-day pronoun usted, used for singular honorific address: Vuestra Merced > vuessa merced > vuessarced > vuessansted > vuessasted > voarced > vuested > usted.

This process derived pronouns from similar expressions for honorific singular address in related languages, as shown in (39). Note that even though these pronouns were meant for singular address, in many cases the plural possessive pronoun was used, instantiating further instances of plural being recruited for honorification.

-

(39)

Diachronies of lexicalised honorifics

-

a.

Portuguese Você (from Vossemecê < Vossa Mercê ‘your.pl mercy’)

-

b.

Italian Lei (from La Vostra Signoria ‘your lordship.fem’)

-

c.

Dutch u (from Uwe Edelheid ‘your nobility’)

-

d.

Romanian variations on dumneavoastră and dumneata (from Dumnia Voastra ‘your.pl grace’ and Dumnia Ta ‘your.sg grace’ respectively)

-

e.

Polish variations on Pan (from moj miłościwy Pan ‘my merciful Lord’)Footnote 8

-

f.

Hebrew adoni (from adon-i ‘my master’)

-

a.

These honorifics do not trigger unique honorific agreement, but trigger the agreement that accurately reflects their nominal origins. Such mismatches systematically pertain with Portuguese (40a), Italian (40b), Dutch u (40c), Romanian dumneavoastră (40d), Polish Pan (40e), Hebrew adoni (40f). In the Italian example (39b), there is an additional mismatch in gender if it is directed towards a male addressee. This is because Lei is grammatically feminine, a remnant effect of the possessive pronoun undergoing gender concord with its feminine head noun Signoria ‘lordship.fem.’

-

(40)

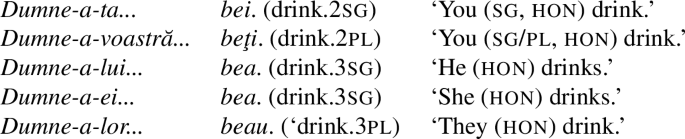

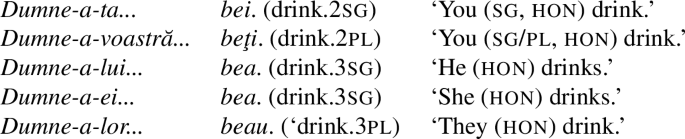

For instance, Romanian dumneavoastră, being derived from Dumne ‘lord’ and avoastră 2pl.poss, was grammatically 2pl, and so triggers 2pl agreement in (40d). In fact, Romanian has developed a whole host of honorific pronouns which are obviously not dedicated as they vary systematically in person, number, and gender (Stavinschi 2015: 36), in accord with the possessive suffixes which are attached to the feminine noun dumne ‘lord’ via the possessive article -a. The agreement of each form reflects their diachronic origins, exemplified for all honorific pronouns as subjects of a bea ‘to drink’ in (41).

-

(41)

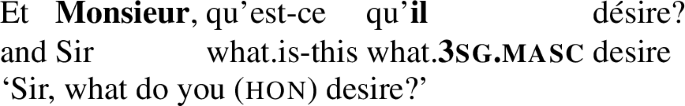

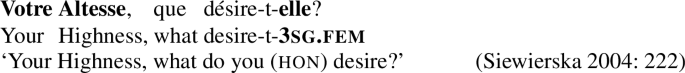

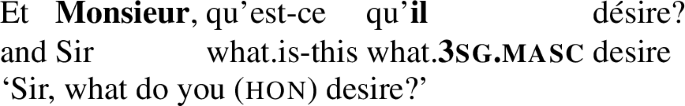

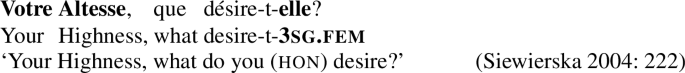

In French, a level of politeness higher than vous (albeit stilted) is possible with these abstractions, which trigger third person agreement. (42) shows that use of the title Monsieur ‘sir’ for honorific address requires the third person pronoun il for co-reference, creating a now-familiar person mismatch. (43) additionally shows that the grammatically feminine abstraction Votre Altesse ‘your highness’ for honorific address towards a man requires the feminine pronoun elle for co-reference, creating mismatches in both person and gender.

-

(42)

-

(43)

We see that lexicalised honorifics never trigger dedicated honorific agreement. Rather, agreement simply reflects the original featural specification of the nominal. This also explains why (37) was ungrammatical: agreement with the German honorific Sie cannot be second person plural, as Sie is third person plural, contrary to what A&N predict.

Thus, [hon] has a very limited range of applications: it triggers impoverishment of certain features on certain pronouns and verbs, but not movement, concord, or agreement, essentially leaving no morphosyntactic trace behind. In fact, the only operation that [hon] is assumed to trigger—impoverishment—requires some very specific stipulations so that it derives only and all the attested patterns. In particular, LF impoverishment must only target number features, while PF impoverishment must only target person features. I say must here, because the two other logical possibilities for impoverishment (that PF impoverishment targets number features; LF impoverishment targets person features) would derive unattested properties of honorifics. I pursue these possibilities below.

Let us first explore LF impoverishment of person, illustrating with Italian. Recall that Italian uses a third person singular pronoun Lei for honorific address. Imagine that [hon] conditions LF impoverishment of the third person feature. In A&N’s theory of person, impoverishment of the third person feature would result in a bare person node, so that the resulting honorific pronoun would be one which is person-neutral: such a pronoun can be flexibly used for honorific self-address, honorific address or honorific reference.

However, person-neutral honorific pronouns are unattested. Italian’s third person pronoun Lei may only be used for honorific address (44a), but not for honorific reference (44b) or honorific self-reference (44c). (Since Italian is a pro-drop language, the following cleft forces an overt pronoun to appear.)

-

(44)

Note that the impossibility of (44c) is not due to a mere error in verbal agreement. This is because even in the grammatical sentence (44a), there is already a mismatch between the values reflected in verbal agreement (3sg) and the referential force (2sg).

Honorification systems where a honorific pronoun has flexible person designations are unattested—there are no languages in which a honorific pronoun has available all three interpretations in (44a–c).

Next, consider PF impoverishment of number, illustrating with French (a language which would normally require LF impoverishment of plural). [hon] would condition PF impoverishment of the plural feature, establishing a surface similarity with plural vous. However, since LF impoverishment has not applied, this pronoun would not be number-neutral, and would only have a plural denotation. The lack of number-neutrality is not the case for French vous, as (33) demonstrates (repeated below as (45)).

-

(45)

We do not find any language where a plural pronoun recruited for honorification is used exclusively towards multiple respected addressees. This is not an attested honorification system. Either a language has two unique honorific forms for singular and plural address (as in Spanish usted/ustedes), or a recruited form is number-neutral (as in French vous, German Sie).

In principle, to pair a type of phi-feature with a type of impoverishment is licit. However, once the “wrong” feature is targeted at the “wrong” level of interpretation, then we derive unattested honorification patterns: namely, honorific pronouns which are person-neutral or exclusively plural. These are ad hoc stipulations required for an impoverishment analysis for honorifics.

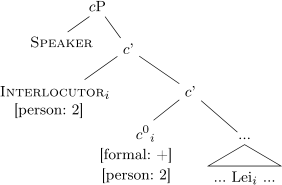

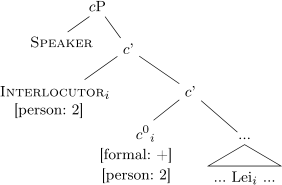

3.3 Portner, Pak and Zanuttini (2019): Agreement

Similar in spirit to A&N’s impoverishment analysis is Portner, Pak and Zanuttini (2019) (henceforth PPZ), who also propose a dedicated feature for honorification, [formal], sensitive to whether the interaction calls for formality or not.

Like much previous work on speaker-addressee relations, components of the speech act are assumed to be syntactically encoded (e.g. Speas and Tenny 2003; Haegeman and Hill 2013) so that syntax makes available the (null) abstract representations of Speaker and Interlocutor. PPZ’s feature [formal] originates on \(c^{0}\), a high functional head above CP, so that \(c^{0}\)P is the syntactic locus for utterance-level meanings. [formal] can be copied onto bound pronouns in the domain of \(c^{0}\) via an operation similar to Kratzer’s (2009) Feature Transmission.

In this analysis, all second person pronouns are bound by Interlocutor via operator-variable agreement (the operator being Interlocutor, and the variable being the pronoun). \(c^{0}\) is the functional head mediating this agreement. Having this agreement relationship with Interlocutor is what makes a pronoun second person, as PPZ assume that pronouns are minimally specified when they enter the derivation (à la Kratzer 2009). This configuration is illustrated in (46) with the Italian honorific pronoun Lei. The honorific, the Interlocutor head, and the \(c^{0}\) head are all in an agreement relation involving a [formal] feature.

-

(46)

What determines the form of the honorific pronoun is a set of spell-out rules sensitive to the specification of the binary feature [formal]. When a pronoun is bound by Interlocutor, and c is valued [-formal], it is spelled out as tu. When a pronoun is bound by Interlocutor, and c is valued [+formal], it is spelled out as Lei. This is schematized in (47).

-

(47)

-

a.

(pronoun) → tu / Interlocutori ... \(c^{0}_{[\mathtt{-formal}]}\) ... __

-

b.

(pronoun) → Lei / Interlocutori ... \(c^{0}_{[\mathtt{-formal}]}\) ... __

-

a.

However, this denies any relationship between polite second person Lei and the homophonous informal third person lei in Italian. Recall from Sect. 2.2 that Lei is a recruitment of third person, but this recruitment is left unexplained in this analysis. As PPZ’s analysis relies on highly specific spellout rules for the honorific pronouns of each language, it becomes ad hoc as to which pronoun can be bound in the honorificity-producing configuration in (47b). In principle, it is possible for first-person pronouns to be recruited for addressee honorification, but this is typologically unattested, as shown in Sect. 2.5.Footnote 9

As a result, PPZ do not explain the robust typological trends in recruitment; the authors themselves state that their analysis “can’t provide a detailed discussion of the mapping between the abstract features and the features on the [polite] pronouns” (Portner et al. 2019: 31). While this was never an analytical goal of [hon]- or [formal]-based theories, leaving the typological trend unacknowledged is an unparsimonious move.

Hence, whether an analysis of honorific pronouns is based on impoverishment triggered by [hon], or agreement involving [formal], a feature dedicated for honorification does not capture—or explain—significant typological trends regarding the shape of honorific pronouns. In some cases, the operation proposed may derive typologically unattested forms. Avoiding dedicated features for honorification, the next section proposes an alternative analysis.

4 Proposal: Honorifics without [hon]

This section puts forward a proposal of honorifics without [hon] or [formal]. The proposal consists of two main ingredients: semantic markedness (Sect. 4.1), and the introduction of an avoidance-based pragmatic maxim, the Taboo of Directness (Sect. 4.2). The analysis is shown to extend to both honorific reference (Sect. 4.3) and to non-pronominal domains (Sect. 4.4). Such an account is shown to have empirical, analytical, and theoretical advantages (Sect. 4.5).

4.1 The emergence of the semantically unmarked

Section 2 showed that plural number, third person, and indefinites are consistently recruited for honorification cross-linguistically. Conversely, singular number, first/second person, and definites are never recruited for honorification.

Here, I show that honorifics do not recruit random values, but semantically unmarked values. In what follows, I will show that plural, third person, and indefinites are semantically unmarked. Of course, what is unmarked in a given language may be subject to language-specific variation, but for ease of exposition, I will mostly illustrate with English (although, to establish this in any given language requires detailed semantic fieldwork with the aim of establishing semantic markedness clines, which has not yet been conducted for many other languages).

A semantically unmarked element is said to have default or neutral interpretations (e.g. Sauerland 2008b). This means that, given a pair of values in the same category (e.g. sg versus pl in the category of number), the less marked element is compatible with a wider range of contexts because it carries a weaker presupposition than its marked counterpart.

Before we illustrate this notion for phi-features, it is important to clarify that the concept of semantic markedness is independent from that of morphological or syntactic markedness. Morphological markedness relates to the presence of overt encoding of some grammatical feature. For instance, plural is said to be morphologically marked, as it is often overt (like English -s). On the other hand, syntactically marked categories trigger exceptional syntactic behavior; for instance, plural triggers omnivorous agreement (e.g. in Georgian; Nevins 2011), is susceptible to ϕ-neutralization (e.g. Long Distance Agreement in Basque; Etxepare 2006) and is also more susceptible to agreement errors (e.g. Eberhard 1997; Tucker et al. 2015). Thus, across these distinct notions of “markedness,” some form of extra complexity is involved (Haspelmath 2006: 26).

Importantly, it is the notion of semantic markedness which is relevant to this proposal. This is an empirical issue: there are no languages in the sample that recruit the morphologically or syntactically unmarked option for honorification. For instance, no language recruits the singular, which is both syntactically and morphologically unmarked.

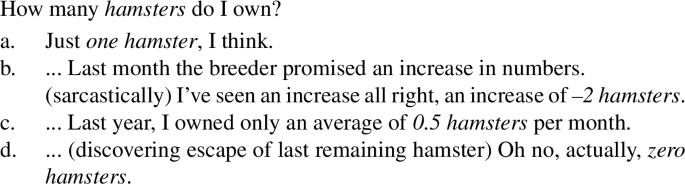

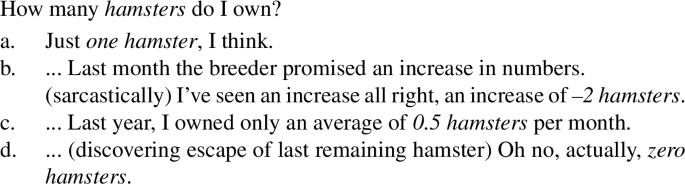

In singular-plural number systems, plural is said to be semantically unmarked (Krifka 1989; Croft 2003; Sauerland 2003, 2008b; Sauerland et al. 2005; Spector 2007; Zweig 2009; Bale et al. 2011; a.o.).Footnote 10 This is because the denotation of the plural can entail singular meanings, giving rise to inclusive interpretations of the plural (one or more). This shows that plurals are not restricted to exclusive interpretations (more than one) as traditionally thought. Consider the monologue in (48), where the speaker is contemplating pet hamsters past and present.

-

(48)

(48a) contains a singular NP (one hamster). Yet, it is still a felicitous answer to the question containing a plural noun (hamsters), showing that the plural form can be felicitously used to inquire about individuals. (48b–d) are also possible answers: even though they denote neither pluralities nor individuals (–2 hamsters, 0.5 hamsters, 0 hamsters), plural marking is obligatory. This shows that plural is compatible with a wider range of uses, while singular marking is only compatible with a cardinality of 1 as in (48a).

This number-neutrality of plural forms fits with the observation that honorific pronouns are number-neutral: they can be used to indicate respect towards one or multiple persons. For example, this is the case for French vous, as was demonstrated in (33).

Quantificational contexts are also useful here. In scenarios involving mixed categories, the semantically unmarked value surfaces under quantification. Consider (49) with the universal every:

-

(49)

Every girl owns hamsters.

(49) is compatible with a scenario where each girl owns exactly one hamster. However, it is also compatible with a mixed scenario, where some girls own exactly one hamster and other girls own multiple hamsters. In such a mixed scenario, plural marking is obligatory, again showing that plural is less marked.

Thus, (48) and (49) show that the denotation of plural contains that of the singular: plural can refer to and quantify over both non-atomic and atomic individuals, but singular may only refer to and quantify over atomic individuals. Thus, plural is less marked than singular in the category of number.

The quantification test can also be applied to the category of person. In scenarios involving mixed persons, third person agreement surfaces under quantification, showing that third person is the least marked person. Imagine (50) was uttered in a scenario where us denotes a mixed-person group of the speaker, the addressee, and a third person. Here, the anaphoric pronoun can only be in third person (his/her).

-

(50)

Every one of us has to call his/her/*my/*your mother. (Sauerland 2008b: 72, adapted)

Consider also imposter phenomena (e.g. Collins and Postal 2012; Podobryaev 2017), where third-person expressions can take on first or second person reference. (51) shows that the third-person nominal, the authors, may point to first person:

-

(51)

[At a conference] The authors will now show that...

Similarly, (52) shows that another third-person nominal, my one and only, may point to second person:

-

(52)

[To her boyfriend on Valentine’s Day] I give this rose to my one and only.

Crucially, imposters cannot be of any other person: first and second person expressions cannot take on non-canonical points of reference; only third person expressions can. This restriction on the shape of imposters suggest that third person is the least marked person.

Moving onto definiteness, it is widely assumed that definites contain additional presuppositions of uniqueness and/or familiarity compared to their indefinite counterparts (e.g. Strawson 1950; Heim and Kratzer 1998; Heim 2011). (53) illustrates this briefly. The definite article in English can only be felicitously used in a context where there is a salient or previously-mentioned hamster in the discourse (53a). Otherwise, its indefinite counterpart must be used (53b).

-

(53)

-

a.

I’ve picked up the new hamster from the store.

-

b.

I’ve picked up a new hamster from the store.

-

a.

We see that indefinites are less marked, as they carry weaker presuppositions and can thus be felicitously used in a wider range of contexts.

Since the typology mostly consists of non-European languages, readers may wonder about the validity of the previous examples which were exclusively given in English. Since the proposal is typologically motivated, a note on the universality of these markedness clines is in order. Given practical constraints, I cannot present language-specific markedness diagnostics for all 120 languages that are eventually considered. In principle, to formulate any language universal is an unattainable goal, given the impossibility of covering all languages and of obtaining negative evidence for each language. However, stipulations of this type are necessary for theoretical work of this type to progress. It is important to note here that the universality of these markedness clines is an assumption, not a proven fact.

However, making this assumption is neither controversial nor futile. It is not controversial: all existing work on cross-linguistic semantic markedness, while not comprehensive, finds that plural is semantically unmarked. For instance, Yatsushiro et al. (2017) present experimental evidence supporting the hypothesis that the plural is semantically unmarked across 18 European languages. (Owing to a dearth of relevant work, the universality of third person and indefinites as semantically unmarked is not so clear.) It is not futile: once the uniformity of markedness clines is assumed, the proposal is able to make concrete and testable predictions for possible cross-linguistic variation. Later sections show that my predictions are indeed borne out for all languages in the sample.

Since I claim a close connection between semantic markedness and honorification, I make the following typological predictions: all languages which recruit plural for their honorifics are languages with semantically unmarked plural; all languages which recruit third person for their honorifics are languages with semantically unmarked third person; all languages which recruit indefinites for their honorifics are languages with semantically unmarked indefinites. The semantic unmarkedness of plural, third person, and indefinites are assumed to be universal (modulo the disclaimer above).

Summing up, plural number, third person, and indefinites have more inclusive interpretations, as they are more permissive in the range of possible interpretations compared to their counterparts. A formalization of markedness is given below in terms of presuppositional strength. The presuppositions carried by phi-features are given below using Heim’s (2008) notation, where presuppositions are stated after a colon. Plural, third person, and indefinites are the semantically unmarked elements, carrying no presupposition.

-

(54)

Presuppositions on number

-

a.

〚pl〛 = λ\(x_{e}\) . x

-

b.

〚sg〛 = λ\(x_{e}\) : |x| = 1 . x

-

a.

-

(55)

Presuppositions on person

-

a.

〚3〛 = \(\lambda x_{e}\) . x

-

b.

〚2〛 = \(\lambda x_{e}\) : x is the hearer of the discourse . x

-

c.

〚1〛 = \(\lambda x_{e}\) : x is the speaker of the discourse . x

-

a.

-

(56)

Presuppositions on (in)definites

-

a.

〚indef〛 = \(\lambda x_{e}\) . x

-

b.

〚def〛 = \(\lambda x_{e}\) : x is familiar or unique in the discourse . x

-

a.

Significantly, it is precisely the semantically unmarked values—and only these values—that are co-opted for honorification, leading to an emergence of the semantically unmarked in honorific contexts. What enables semantically unmarked elements to be co-opted in this way? The next section addresses this.

4.2 Whence honorific meaning?

It is a common intuition that avoidance, or social distancing, forms the core of polite behaviors. Interactions with respected persons are typically characterized by avoidance behaviors: refraining from direct eye contact and/or physical contact, hedging, circumlocution, being vague, and so forth. Such strategies have been formalized in previous anthropological research by Brown and Levinson (1978) as strategies addressing negative face: “the basic claim to territories, personal preserves, rights to non-distraction—i.e. to freedom of action and freedom from imposition” (Brown and Levinson 1978: 61). In this way, negative politeness strategies maximize autonomy to the addressee and minimize any potential obstruction that the speaker imposes.

Here I formalize honorific meaning as the result of an interaction between semantically unmarked forms, social taboo, and Maximize Presupposition (Heim 1991). The resulting account introduces a morphopragmatic algorithm to derive honorific meaning, in a way that links semantic unmarkedness to negative politeness.

We have seen that cross-linguistically, honorifics are realized by semantically unmarked forms. The present step is to assume that, in contexts requiring respect, there exists a social taboo that militates against direct behaviors, in favor of avoidance behaviors. Call this the Taboo of Directness (ToD), a pragmatic maxim for politeness, formalized in (57):

-

(57)

Taboo of Directness (ToD): In respect contexts, use the form with the weakest presupposition.

When applied to morphosyntactic features, then, ToD will favor the use of semantically unmarked forms over use of semantically marked forms. Recall that semantic markedness was cashed out in terms of presuppositional strength: semantically marked elements carry stronger presuppositions than their unmarked counterparts; making plural, third person, and indefinites semantically unmarked as stated in (54)–(56) above.

ToD derives avoidance behavior as follows. Less semantically marked forms are more compatible with politeness because they have wider denotations and are thus compatible with a wider range of contexts. When a semantically unmarked form is used, then, there is a certain ambiguity as to the precise denotation that the speaker intends. Conversely, if the speaker had chosen to use a more semantically marked form, then there would be no such vagueness: the intended denotation is more precise because the more marked forms are only compatible with specific contexts. This vagueness (via choice of the less marked form), combined with the taboo against specificity (resulting in relinquishment of the more marked form), allows ToD to formally capture the intuition that avoidance is a key component of respect.

Let us illustrate how honorific meaning is derived via use of honorific plural in French vous (2), repeated below as (58).

-

(58)

As (56) was uttered in a context requiring respect (in French, this might be a student addressing a professor), ToD applies. In French, ToD is parameterized to apply to the domain of number, where it militates against the use of the singular form (since it is more semantically marked). The speaker must then resort to the remaining alternative, the plural form (since it is less semantically marked). As a pragmatic maxim which picks out the form with the weakest presupposition, ToD shrinks the set of available forms from sg, pl to pl. The plural verbal agreement which appears is treated as a mere reflex of dependency with plural vous. Since ToD enforces the use of vous for honorification, agreement upstream will be plural also.

This vagueness is costly, however, particularly because ToD forces the speaker to choose the less marked form whenever possible, regardless of the real-world denotation. Even though the speaker in (2) is aware that her addressee is singular, ToD forces her to use a plural form. By doing so, ToD conflicts with another, more general pragmatic maxim, Maximize Presupposition! (henceforth MP!). MP! states that the form carrying the strongest presupposition should be used whenever possible (59):

-

(59)

Maximize Presupposition! (Heim 1991) Choose the strongest presupposition compatible with what is assumed in the conversation.

MP! requires the speaker to choose the singular form, because it is the singular which carries the strongest presupposition compatible for the following reason. In the context of one addressee, only the singular form presupposes a cardinality of one; the plural has inclusive semantics and carries no presuppositions about cardinality. If MP! did indeed hold in honorific contexts, we would find none of the mismatches which characterize honorifics.

This means that MP! is flouted in honorific contexts, the culprit being the politeness consideration that is ToD. While featural mismatches have been used throughout the paper to illustrate instances of honorific meaning, a mismatch is not necessary to trigger an honorific inference. Rather, what is necessary is the following ranking between the two pragmatic maxims, such that ToD >> MP!. Thus, honorific meaning arises from the interaction between these two pragmatic maxims.

Since this suggests that the ranking ToD >> MP! is sufficient to trigger an honorific inference, it may be instructive to consider cases where the rankings ToD >> MP! and MP! >> ToD are indistinguishable from one another. This concerns “ceiling” cases, where honorific plural overlaps with actual plural cardinality, resulting in no featural mismatch. For instance, French honorific vous is number-neutral: it can be felicitously used for honorification towards a plural addressee (60).

-

(60)

Here, I claim that the honorific inference is still present. Featural mismatches have been used extensively throughout this paper because they are characteristic of honorification, presenting a starting puzzle with the phi-featural mismatches that honorification creates. However, while mismatch is characteristic of honorification, it is not necessary. I propose that the interaction of ToD and MP! in cases of mismatch eventually leads to conventionalization, so that the use of the presuppositionally weaker feature is taken to indicate honorification across the board, even when no mismatch pertains.Footnote 11 (Such conventionalization also drives the diachronic development of honorifics, which is covered later in Sects. 3.2 and 6.3.)

It is worth emphasizing that the notion relevant to ToD is that of semantic markedness, as neither syntactic nor morphological markedness bears on the range of meanings an element may have. What matters for the pragmatic maxim being proposed is presuppositional strength, not morphological complexity (as honorifics are form-identical to the features they recruit), or syntactic exceptionality (as honorific meaning does not appear or disappear with the type of construction used; neither does honorificity trigger certain syntactic operations).Footnote 12

We can now relate the typological patterns laid out in Sect. 2 to the current proposal. Since honorifics take on such diverse forms, parameterization determines which phi-category is relevant for ToD in a certain language. For languages with honorific plural, ToD pertains to number; for those with honorific third person, ToD pertains to person; for those with honorific indefinites, ToD pertains to definiteness. Which phi-feature is targeted by ToD is arbitrary; more detail on this is given in Sect. 5.2. Despite this degree of arbitrariness, ToD does not derive unattested typological patterns: it is impossible to apply ToD such that honorific singular, honorific local person, or honorific definites result. This is because ToD >> MP! in all honorific contexts, and ToD enforces the use of the least semantically marked form.

ToD is meant as a universal; for languages without grammatical honorification, I assume that ToD does not target any of the aforementioned phi-features. This does not necessarily mean that ToD is entirely dormant: again, it may target any grammatical category exhibiting a presuppositional cline, not just the categories of number, person, and definiteness. So far, pronouns have been used to illustrate the bulk of honorificity phenomena, but only as proxies for illustrating the phi-featural presuppositions located on them. Thus, the domain of ToD is not restricted to pronouns, or even phi-features located on pronouns; in principle, the effects of ToD may be found wherever presuppositional clines exist.Footnote 13 Indeed, its effects on lexical presuppositions and imperatives are later presented in Sect. 4.4.

In some cases, verbal agreement was exclusively used to diagnose honorificity; for instance, for Assiniboine’s honorific plural (11) and for Central Alaskan Yupik’s honorific third person (20) (both repeated below).

-

(61)

-

(62)

Here, the locus of honorificity is not located on a pronoun but on an agreement morpheme. The approach to verbal agreement goes along the same lines of reasoning: since ToD acts on presuppositional clines, it does not matter that the cline is located in the verbal domain. Since bound agreement morphemes index phi-features just as pronouns do, they are not exempt from ToD.Footnote 14

Readers might recall from Sect. 3.2 that A&N overgenerate honorific pronouns used exclusively for plural antecedents, and person-neutral honorific pronouns. First, since plural is the presuppositionally weakest number, it would be very surprising on this account if plural honorification had a dedicated marker: this would mean that different forms are used to honorify plural antecedents and singular antecedents. The number recruited for honorification, whether for plural or singular antecedents, is predicted to be plural and plural only.

However, this account does not rule out the existence of person-neutral honorific pronouns either. Since third person is the presuppositionally weakest person, recruiting a third person form to span honorific reference, honorific address, and honorific self-address should be plausible, resulting in ceiling cases pertaining to person. As mentioned in the critique of A&N earlier, these are not attested. Under this account, though, this may be due to a purely empirical gap (since person-recruiting honorification systems are much less attested in the typology than number-recruiting honorification systems are). This might also be due to an economy consideration: in the number-related ceiling cases, plural spans two feature values (singular, plural); while for hypothetical person-related ceiling cases, third person would span three feature values (first, second, third person). Since the present account already places an emphasis on feature economy by eschewing a dedicated feature [hon] in favor of repurposing existing features, the latter explanation for the inexistence of person-neutral honorifics is adopted here.

Importantly, no machinery specific to honorification is assumed in this account. Semantic markedness and MP! are well-established tools and have been proposed for wide-ranging phenomena elsewhere in formal semantics/pragmatics. ToD is indeed an innovation, but note that it simply reflects Brown and Levinson’s (1978) notion of negative politeness.

4.3 Honorific reference

Given that ToD is a grammatical manifestation of negative politeness, which confers autonomy and independence to an interlocutor, it is important to consider how honorific reference is derived, in addition to honorific address. When a speaker is merely referring to a third person who is not present, one might wonder if the considerations of taboo and avoidance still apply.

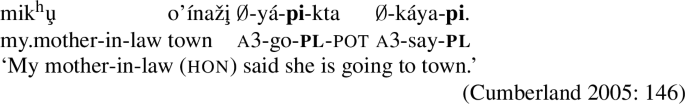

I propose that honorific reference is derived exactly parallel to honorific address. Once a tabooed relation is established, it is equally prohibitive to refer to that relation as it is to address them. Both linguistic and anthropological work highlight this feature of taboo, particularly those of in-law taboos. Rushforth (1981:35–36) notes the following rules of in-law avoidance in the Northeast Athabaskan-speaking Bear Lake Dene community. At all times, one is to avoid unnecessary conversation with an in-law. If conversation is necessitated, it should be done indirectly, through an appropriate proxy. If an appropriate proxy cannot be found, only then can one speak directly to an in-law, but only in the affinal speech style, characterized by use of the honorific plural. Rushforth explicitly notes the “importance of restraint, individual autonomy, and independence,” a striking parallel to the notion of negative politeness which ToD reflects. Previous studies about the Dene ethnographic group in general (Helm 1965; Savishinsky 1970) are concordant regarding this practice.

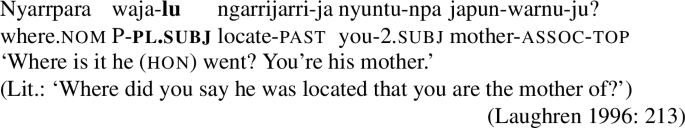

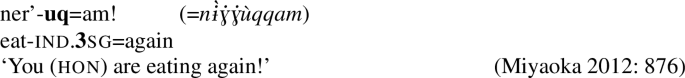

Similar taboos can be found in many other language communities. In Guugu Yimidhirr, brothers-in-law “not only use the respectful vocabulary; they sit far apart, orient their bodies so as not to face one another, and avoid direct eye contact” (Haviland 1979: 170). In Warlpiri, tabooed relations are identified as in-laws, co-initiates, and opposite-sex relations. These taboos are arbitrated by honorific plural, regardless of whether the recipient is an addressee or a referent. Laughren (1996: 192) notes that speakers “use the plural pronoun nyurrurla and not the singular nyuntu(lu) to address or refer to a different sex sibling.” Furthermore, plural is used to refer to in-laws, as in (63) where the speaker asks after his son-in-law with the plural. Note also his explicit avoidance to the “son-in-law” relation, which is only alluded to by pointing out that his addressee is his son-in-law’s mother.

-

(63)

The reader might recall that Warlpiri has been used to illustrate honorific address towards a co-initiate in (14) above. This shows that honorific plural pertains for both address (14) and reference (63), and the act of “conferring independence” does not depend on whether an interlocutor is in direct earshot or not.

There are also languages where the taboo in place affects honorific self-address (i.e. self-humbling), honorific address, and honorific reference, affecting all three grammatical persons. In Iduna (Papua New Guinea, Oceanic), honorific use is driven by matriarchy, and “a woman who is a mother is addressed, responds and is referred to in the plural” (Huckett 1974: 74). This pervasiveness of taboo across grammatical persons can also be found in two Austroasiatic languages, Jahai (Fleming 2017: 109) and Ho (Anderson et al. 2008: 209).

Table 5 summarizes the languages in my typology which display honorific reference, the taboos driving honorific reference, and whether the taboo also extends to humbling self-address and/or honorific address. In all cases below, the honorification strategy involves honorific number.

A more compelling case for the pervasiveness of taboo may be found with “bystander honorifics,” used towards tabooed relations who are mere bystanders to the discourse. In Dyirbal (Aboriginal Australia, Pama-Nyungan), a speaker must switch to the avoidance register if a tabooed kin is within earshot, even if the speaker was neither addressing nor referring to the kin (Dixon 1972: 32). Bunuba is similar, with mother-in-laws being the bystander to consider (Rumsey 1982: 161). Keating and Duranti (2006: 148) note for Ponapean that “when the chief or some other high status person is present, the use of honorifics becomes relevant on that basis alone. Radio announcements are therefore made using honorific forms.”

Hence, the use of honorific registers is driven by the speaker’s relation to the recipient, and does not depend on whether the recipient is an addressee, a referent, or a bystander. Thus, the notion of negative politeness driving ToD can still be maintained, if we agree with previous anthropological studies that social taboos are pervasive enough so that “mere” reference is also considered an infringement of autonomy. If we expand the notion of conferring autonomy so that it also respects the sovereignty of the individual (the right to one’s bodily integrity and to one’s exclusive control of their social life), then negative politeness is still in effect, whether it grants autonomy (in the case of honorific address) or sovereignty (in the case of honorific reference).

4.4 Further support: ToD in other domains

4.4.1 Lexical

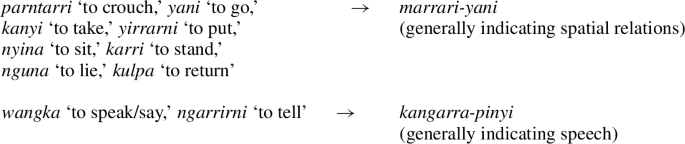

Languages can also deploy ToD on lexical presuppositions. To illustrate this, we turn to semantic bleaching, the phenomenon whereby multiple, lexically distinct verbs in the ordinary register are replaced wholesale by a vaguer “catch-all” verb in the avoidance register. Here, I illustrate with the in-law avoidance registers of Aboriginal Australia.

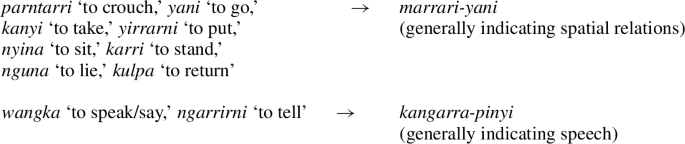

(64) exhibits the semantic bleaching in the avoidance register of Warlpiri. Multiple lexically distinct verbs in the ordinary register are conflated into one verb in the avoidance register used with brothers-in-law (Laughren 2001:205).

-

(64)

(65) shows semantic bleaching in the Guugu Yimidhirr (Australia, Pama-Nyungan) avoidance register, with the same many-to-one correspondence between the ordinary and brother-in-law registers (Haviland 1979: 218).

-

(65)

Semantic bleaching in avoidance registers makes fewer lexical presuppositions about the action carried out by honorified referents. For instance, both ‘to go’ and ‘to paddle’ presuppose motion, but only ‘to paddle’ carries the additional presupposition that this motion was via water, and accomplished with some instrument. This suggests that ToD is also active in non-pronominal domains. Semantic bleaching serves the same purpose as using presuppositionless forms for honorific pronouns: both strategies avoid individuation of the referent, thereby respecting negative face.

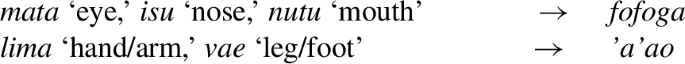

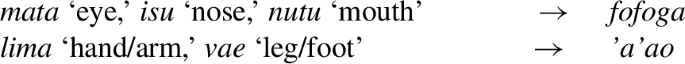

This phenomenon can be also found in Australasia. In Samoan (Polynesia, Oceanic), there are distinct common vs. high-status registers, with the high-status register exhibiting avoidance-based polysemy in the nominal domain (Keating and Duranti 2006: 153):

-

(66)

Semantic bleaching is a typologically robust phenomenon, found the languages shown in Table 6.Footnote 15

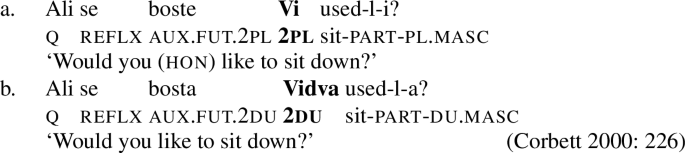

4.4.2 Imperatives

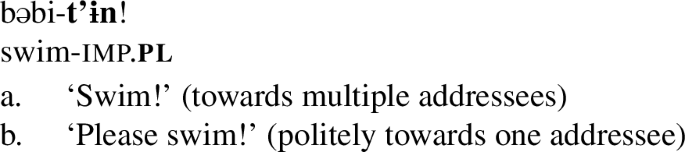

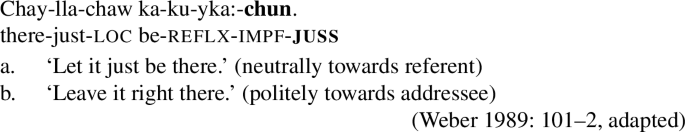

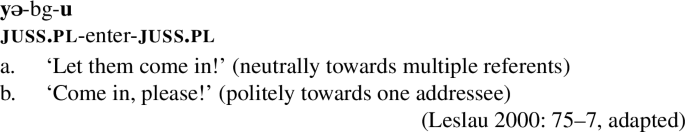

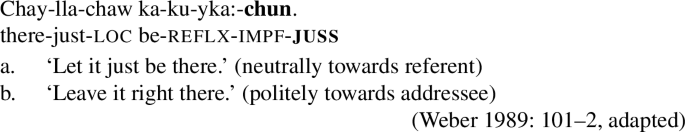

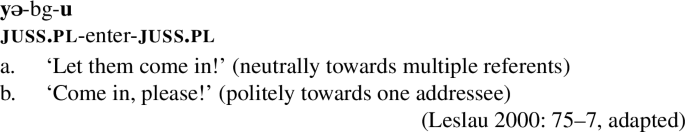

Politeness considerations are especially salient in imperatives, as imperatives are manipulative speech acts. A preliminary survey of polite imperatives finds that the same patterns hold: only plural, third person, and the combination of third person plural are attested as imperative softening strategies.

Languages may distinguish singular from plural imperatives (see WALS, Chap. 70), so that they morphologically distinguish imperatives directed towards one vs. multiple addressees. It is to such languages that we now turn, as it is only in these languages where honorific plural is discernible in imperatives.Footnote 16

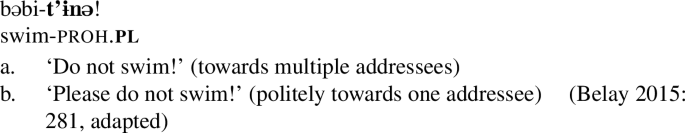

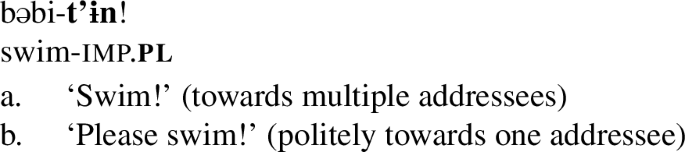

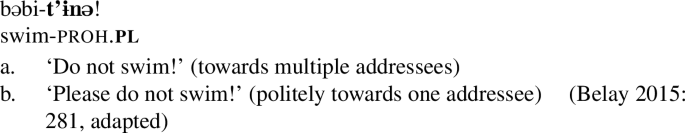

In Xamtanga (Ethiopia, Cushitic), the singular imperative is null-marked, distinguishing from the plural imperative which is marked with -t’ɨn. For a polite imperative towards one addressee, it is the plural form which is used, resulting in the ambiguity in (67a–b). Such ambiguity is also exhibited in the prohibitive, as in (68)[a–b].

-

(67)

-

(68)

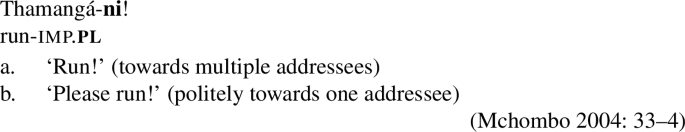

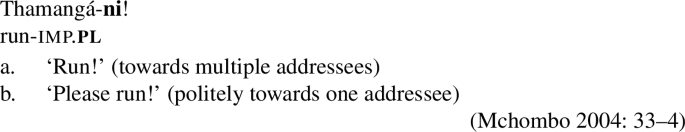

Chichewa (South/East Africa, Bantu) also employs honorific plural in its imperatives. Singular imperatives consist of the bare verb stem, while plural imperatives add the enclitic -ni. As in Xamtanga, the Chichewa plural imperative may also be used politely towards one addressee:Footnote 17

-

(69)