Abstract

This paper draws attention to various environments in Greek which show that imperatives convey possibility and not necessity as widely assumed in the literature. The interaction of imperatives with other operators reveals the presence of an existential operator. At the same time, however, it is shown that imperatives cannot be analysed as invariably conveying possibility. Instead, I suggest an analysis in which imperative verbal mood is semantically contentful, triggering a presupposition that results in a domain restriction for the set of evaluation worlds. Combining insights from both the modal (Schwager 2006; Kaufmann 2012) and the minimal approach (Portner 2004, 2007), I show that we can have a modalized minimal analysis if we take imperative verbal mood to be contentful at a presuppositional level. This twist allows us to capture the variable quantificational force of imperatives depending on the environment they appear in.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It is well-known that in many languages imperatives can vary in their contextual interpretation (Wilson and Sperber 1988; Han 2000; Schwager 2006; Portner 2007; Grosz 2011; Condoravdi and Lauer 2012; Kaufmann 2012; von Fintel and Iatridou 2017). To mention only some of the readings, the imperative in (1), depending on the context, can express command, plea, advice, permission, indifference as in (1a–e).

-

(1)

Sign this paper.

-

a.

As a command/request from the chief to the employee.

-

b.

As a plea from a child to her mother to sign a form which provides permission for school trips.

-

c.

As advice to somebody who wonders how to apply for daycare.

-

d.

As permission, although the speaker might not fully agree (…but you should know I don’t agree).

-

e.

As indifference, requiring a continuation like …burn this paper, eat this paper… I don’t really care…

-

a.

As I discuss in the following section, under most analyses the basic interpretation for imperatives is considered to be the strong one (command, request, strong advice) whereas the weak is derived via some additional mechanism. In this work, I draw evidence mostly from the behavior of imperatives in Greek and argue that the weak interpretation (acquiescence in von Fintel and Iatridou’s 2017 terms) is basic and that the stronger one is derived as an implicature. A variety of diagnostics provide evidence that the existential character of imperatives is much more pervasive than previously thought. First, I present scope ambiguities with the focus particle mono ‘only’ and the scalar particle akomi ke ‘even’ in Greek. Moreover, I discuss the distribution of Free Choice Items in imperatives showing that an all-universal analysis cannot straightforwardly account for all the data. These data indicate that imperatives, despite their apparent “imperative” character, can be best analysed as expressing possibility. However, as I show it is problematic to consider possibility as an integral part of the semantics of imperatives because, when imperatives combine with an overt adverbial modal in Greek, they acquire the force of the adverbial. This variability in force indicates that the imperative form does not involve an operator with fixed quantificational force.

In order to capture this flexibility in the interpretation of imperatives, I argue that the imperative consists of a mood-phrase taking as its argument a proposition (a function from worlds to truth values) with an imperative feature (+imp). The imperative feature is critical since it introduces certain presupposition restrictions on the world variable, in particular the world variable is restricted to worlds consistent with the speaker’s desires, thus resulting in a bouletic modal interpretation. By stripping the imperative form from the modal operator, the variability in the quantificational force of imperatives can be explained in a more flexible manner. If an imperative is embedded under a quantificational adverbial it acquires its force whereas in the absence of a quantificational operator existential closure applies, deriving a possibility modal interpretation.

While the analysis is designated to account for the facts presented for Greek imperatives, it can be extended to other languages in which imperatives are observed to have variable quantificational force, i.e. allow a variety of acquiescence readings in addition to the strong interpretation. Not all arguments can be extended to other languages. In Sect. 3.1.2 data from Hungarian and Serbian are discussed, replicating the scope ambiguities with only in Greek. In Sect. 3.2 an independent argument from Francis (2019) from the interaction of even with English imperatives is presented, suggesting that a weak existential analysis is extendable to English. A separate question concerns whether the strengthening mechanism suggested in Sect. 6 has to be the same across different languages. I will not get into this discussion as the language discussed is Greek, and strengthening is associated with certain prosodic patterns in Greek.

The paper proceeds as follows: in Sect. 2, I provide some background regarding previous approaches to imperatives focusing on their account for the observed polysemy. In Sect. 3, I present primary evidence mainly from Greek showing that the existential force is more prevalent than previously thought. In Sect. 4 I discuss imperatives which involve an overt adverbial showing that an all-existential analysis cannot account for the available combinations. In Sect. 5, I suggest that we can account for the entire range of data by treating the imperative as a mood-Phrase with a special imperative feature. In Sect. 6, I refer back to plain imperatives which can express command or request. I show that these cases can be best analysed as implicatures derived by exhaustification over focus alternatives. Section 7 concludes and puts forward new questions raised by the proposed analysis.

2 Previous approaches and their perspective towards polysemy

In this section, I present two distinct approaches, under which imperatives convey a strong interpretation. I follow a coarse dichotomy between the so-called minimal approach according to which there is no operator in the semantics, and the modal approach which argues in favor of a modal operator in the semantics (see Iatridou 2008; von Fintel and Iatridou 2017). This discussion will help us test the predictions that these theories make in view of the data presented in Sect. 3 and compare them with the proposed analysis in Sect. 5.

2.1 Minimal approach

The essence of a minimal approach to imperatives is that there is no operator in the semantics of an imperative clause (Hausser 1980; Portner 2004, 2007; Mastop 2005; Pak et al. 2008; Starr 2011; von Fintel and Iatridou 2017; Roberts 2018). The “directive” force of imperatives comes from the pragmatics. The difficulty is to define the exact mechanism that is responsible for turning a property or a proposition into a “directive.” Here I focus on Portner’s (2004, 2007) approach (but see also Starr 2011; von Fintel and Iatridou 2017).

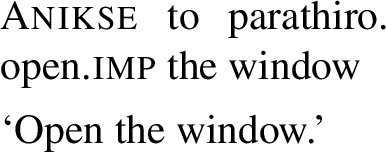

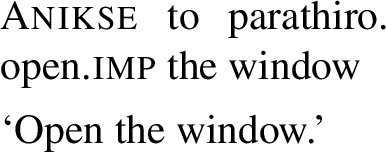

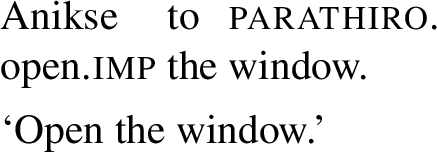

Portner (2004, 2007) suggests that the imperative is a different clause type along with declaratives and interrogatives. Following the Stalnakerian notion of Common Ground (CG), declaratives serve as updates of the information in the CG. Portner suggests a parallel function for imperatives; imperatives add properties to another stack dubbed To-Do-List for each addressee (cf. update of the plan set in Han 2000). The denotation of the imperative is just a property which holds of the addressee (A), as shown in (2) for an imperative clause like Open the window.

-

(2)

Imperative is a property restricted to A:

〚Open the window〛 = λw. λx: x = A. x opens the wnd in w

Similarly to the way in which a declarative proposition adds its content to the Common Ground (CG), and an interrogative to the Question Stack (Q), a successfully uttered imperative adds its content to A’s To-Do-list (T). In Portner (2007), this is formalized as in (3):

-

(3)

Pragmatic Function of Imperatives

-

a.

The To-Do-list function T assigns to each participant α in the conversation a set of properties T(α)

-

b.

The canonical discourse function of an imperative clause \(\phi _{\text{imp}}\) is to add \([\!\![\phi _{\text{imp}}]\!\!]\) to T(addressee). Where C is a context of the form 〈CG,Q,T〉:

C + \(\phi _{\text{imp}}\) = 〈[CG,Q,T(addressee)] ∪ \(\{[[\phi _{imp}]]\}\) 〉

-

a.

The Agent’s commitment principle guarantees that the addressee will try to fulfill as many properties as (s)he can from his To-Do-List. In addition, the To-Do-list imposes an ordering on the worlds compatible with the CG. Portner (2007) makes a direct comparison between what he calls priority modals and imperatives. In a similar fashion that the conversational backgrounds restrict the interpretation of the ordering source in modals, imperatives depend on conversational backgrounds in the context to get their bouletic, deontic or teleological flavor. In this sense, we can think of sub-To-Do Lists for each individual (e.g. a bouletic To-Do List, a deontic To-Do List, etc.). Although such an analysis accounts for the different imperative meanings such as advice vs. command, as Portner himself acknowledges permission readings cannot be derived. Portner (2010) suggests that permission readings arise from conflicting requirements on the To-Do List. Building on the general idea that permissions arise “in the context of a countervailing prohibition” (Kamp 1979), Portner argues that the context in which an imperative is interpreted as a permission typically contains a prohibition. For example, suppose that A’s To-Do List before the speaker utters the imperative eat a banana involves a property, ¬ eat a banana. After the update, A’s To-Do List involves two conflicting properties: eat a banana and ¬ eat a banana. This means that the updated To-Do List is inconsistent and therefore offers a choice to eat or not eat a banana.

However, as von Fintel and Iatridou (2017) discuss, there is an empirical issue with this analysis. In many cases conflicting requirements do not suggest that there is a possibility of choosing among them. Likewise, Portner (2010) acknowledges a similar problem in the following example:

-

(4)

Bring beer to the party tomorrow! Actually, bring wine!

The imperatives in (4) are inconsistent but they do not provide a real choice to the addressee as to whether he brings wine or beer. Portner suggests that in order to induce a choice among conflicting requirements the imperative has to be marked as being permission. In other words the default is that imperatives are interpreted as requirements, yet in some cases imperatives can be marked (by intonation, or by an overt expression like if you want, or by a morpheme in some languages) as permissions.

As von Fintel and Iatridou (2017) argue, this idea is not without problems as by introducing an additional requirement/permission feature, the approach largely loses its advantage over analyses that assume a covert operator. A potential amendment, suggested by von Fintel and Iatridou (2017), is that the property is not added automatically to A’s To-Do List but rather “it is put on the table as a possible addition to A’s To-Do List” (see also Condoravdi and Lauer 2012 on this point). Under this view, the level of endorsement can vary in different contexts. The default case is that speakers fully endorse what they say. However, as they discuss, even in declaratives, the speaker can indicate by rising intonation or a cleft, that (s)he is not entirely sure whether the information (s)he provides is true (cf. Farkas and Bruce 2010; Malamud and Stephenson 2014). Similarly, von Fintel and Iatridou’s (2017) suggestion is that imperatives can express lower endorsement via a rising intonation, or by clearly stating that the speaker has no preference (e.g. I don’t care.) Portner (2018a) proposes a similar distinction between rising and falling imperatives building on Gunlogson’s (2004) analysis of declaratives, suggesting that permission associates with rising intonation. However, all the cases of permission imperatives discussed in this paper are most naturally uttered with falling intonation. Also, Appendix B presents a perception study of imperatives in Greek with a falling boundary tone which can be perceived as permission. Similar data are reported for English by Oikonomou (2016). Although, rising intonation can favor a permission reading, especially in the case of providing advice, it is not a necessary nor a sufficient condition for the emergence of weak readings of imperatives.

2.2 Modal approach

The common thread in the modal analyses of imperatives is that they incorporate a modal operator into the semantics of an imperative clause (Schwager 2006; Crnič and Trinh 2009; Grosz 2011; Condoravdi and Lauer 2012; Kaufmann 2012; Keshet 2012; Keshet and Medeiros 2019).Footnote 1 The exact character of this operator differs across the different approaches. Here we focus on Kaufmann’s (2012) approach on which the present analysis largely builds.

Kaufmann, in her dissertation (Schwager 2006) and later in Kaufmann (2012), analyses the imperative operator as a universal modal. Under this approach the meaning of the imperative is identical to that of a universal modal as shown in (5):

-

(5)

∀-Modal approach:

\([\!\![\text{Open the window!}]\!\!]^{w} = \forall w^{\prime}\) ∈ ∩f(w) [A opens the window in \(w^{\prime}\)]

The fact that there is a modal operator in the semantics allows Kaufmann to use the machinery introduced by Kratzer (1981) in order to account for the variety of interpretations in imperatives. Roughly, by employing different conversational backgrounds for the ordering source, Kaufmann derives wishes (g = what the speaker wants), requests/commands (g = what the speaker orders) and advice (g = A’s preferences, or what is considered to be generally preferred) (see Kaufmann 2012, Sect. 4.1). However, permission and acquiescence readings once more present a puzzle because it is not a matter of a variable ordering source but of weaker force. Among the various types of acquiescence readings, Kaufmann (2012) considers For-example-advice as in (6), the most challenging for a universal analysis.

-

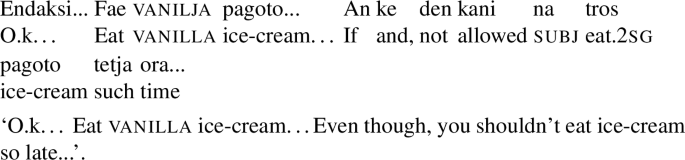

(6)

Examples like (6) as an answer to the question “How could I save money?” clearly convey possibility and not necessity. For these cases, Kaufmann suggests that the universal modal should be reduced to an existential one. The mechanism she suggests is of particular interest for the present analysis because it is a weakening mechanism mirroring the strengthening mechanism proposed in Sect. 6.

In a series of works (Schwager 2005, 2006; Kaufmann 2012), Kaufmann develops an analysis of examples like (6) as inexhaustive possibilities. This means that the default imperative is analysed as an instance of exhaustive possibility. A possibility is exhaustive if it is the only possibility (e.g. The only thing you can do to stop smoking is stop buying cigarettes; Kaufmann 2012: 181–183).

Building on Zimmermann (2000), Kaufmann shows that an exhaustive possibility amounts to a necessity. Under this idea, an imperative is treated as a possibility which is obligatorily exhaustified thus being equivalent to a necessity. Kaufmann (2012) assumes that a covert Exh-operator combined with a possibility modal operator, constitute together the imperative operator. Under this view, when we get a possibility reading there is some mechanism which removes the covert Exh-operator. Kaufmann (2012) takes expressions like for-example to act as anti-exhaustifiers, removing the Exh-operator and licensing a possibility reading. As Kaufmann herself points out, the nature of this exhaustive operator as well as the conditions under which anti-exhaustification occurs require further investigation. Moreover, this analysis raises the question why imperatives should always combine with an Exh-operator.

The idea I pursue here is, in fact, very similar to Kaufmann’s idea of exhaustified possibilities. The difference is that I take exhaustification to be the direct result of an implicature generation mechanism in the presence of alternatives. Under this view, exhaustification will apply when there are certain alternatives which depend on focus marking.

Before closing this section, I will briefly introduce Condoravdi and Lauer’s (2012) approach to imperatives as Effective Preferences, as it differs both from the minimal and the modal approach in that it takes imperatives to always express preferences. The speaker-bouletic nature of imperatives is a basic characteristic that the present analysis shares with Condoravdi and Lauer’s (2012) proposal.

2.3 Condoravdi and Lauer (2012)

Condoravdi and Lauer (2012) analyse imperatives as preferential attitudes. The general idea is that imperatives express a speaker’s preference ordered with respect to other preferences. Under this view every individual has a set of desires, moral codes, obligations, which can be ranked with respect to their importance. Condoravdi and Lauer (2012) define this as a preference structure:

-

(7)

A preference structure relative to an information state W is a pair 〈P,≤〉 where P ⊆ ℘(W) and ≤ is a partial order on P.

Whereas a preference structure can consist of contradictory preferences, the moment an agent has to act he needs to resolve these conflicts. In other words, he needs to make his preference structure consistent. A consistent preference structure is called an effective preference structure. In this model, an imperative sentence expresses the speaker’s Effective Preference at time t (= utterance time). An Effective Preference is the preference which is ranked higher than the other preferences in a consistent preference structure. Therefore, an imperative such as Open the window is interpreted as in (8), in which \(PEP_{w}(Sp, p)\) means that the speaker in c (Sp) is publicly committed at w to act as though p is a maximal element of \(Sp's\) effective preference, i.e. the Sp is committed to the Effective Preference that the addressee in c (A) opens the window in u.

-

(8)

\([\!\![\text{Open the window}]\!\!]^{c} = \lambda \)w. [PEPw (Sp, λu [A opens the wnd in u])]

From this meaning a number of things follow regarding the addressee’s commitment to act as if he has the same effective preference as the speaker. However, treating imperatives as conveying ranked preferences also makes it difficult to account for cases in which imperatives express possibility.

All the analyses I have presented thus far, despite their notable differences, share a common characteristic; they all suggest a strong meaning for imperatives. In the following section, I show that a strong meaning cannot account for a range of environments which I take as evidence for the presence of a weaker operator in the semantics of imperatives.

3 Evidence for the existential character of imperatives

This section focuses on three data points from Greek illustrating the existential nature of imperatives. First, I show that imperatives interact with the particle mono ‘only’ in a similar way to existential modals and not like necessity modals. Thus, I take this as evidence against an underlying universal operator in imperatives. Second, I discuss the interaction of the scalar additive particle akomi ke ‘even’ with imperatives, showing that its interpretation can only be accounted if there is an underlying existential operator. These two environments also provide evidence for the existence of an operator in the semantics of imperatives against the minimal approach. The third argument involves the licensing of Free Choice Items (FCIs). These data converge to an existential analysis of imperatives which, in turn, raises new questions.

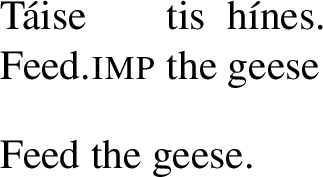

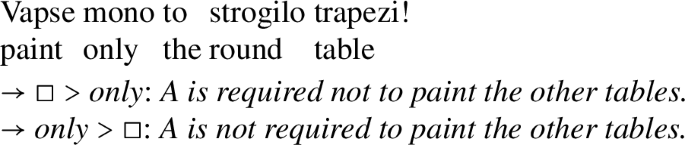

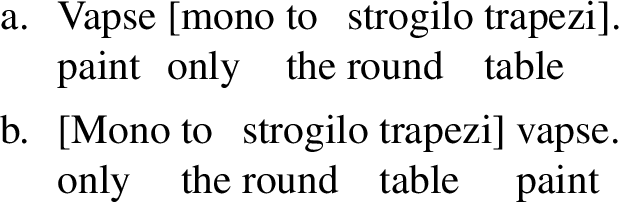

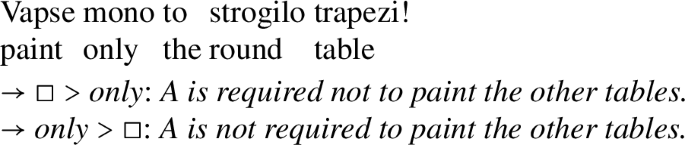

3.1 Only and imperatives

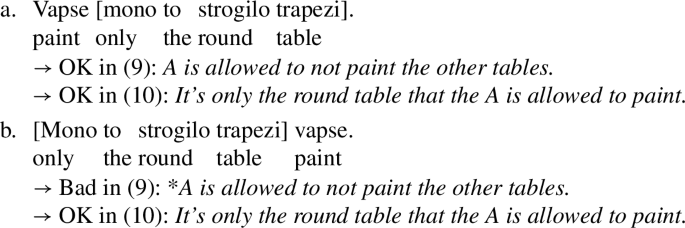

Haida and Repp (2012) show that an imperative containing only is ambiguous. The dialogue in (9), facilitates the reading that it’s OK to not paint the other tables whereas in (10) the most favored reading is that it’s OK to paint the round table but it’s not OK to paint the other tables. From now on I will refer to the reading in (9) as permissive and to the reading in (10) as prohibitive.

-

(9)

A: You’ve asked me to paint those tables but I’m really tired and don’t feel like doing something really useful today.

B: Only paint the round table.

-

(10)

A: Oh, I feel like doing something really useful today. I think I’ll paint the tables over there.

B: Only paint the round table.

(Haida and Repp 2012: 308)

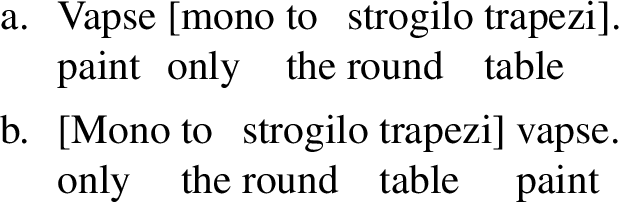

I argue that the ambiguity in (9–10) is best explained as a scopal ambiguity. Evidence for this comes from Greek, where overt focus movement is shown to resolve scope ambiguities. Building on the Greek data with movement, I argue that the ambiguity can be best explained if we treat the imperative modal operator as an existential modal.

3.1.1 Evidence from overt movement in Greek

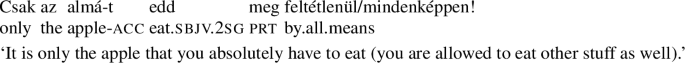

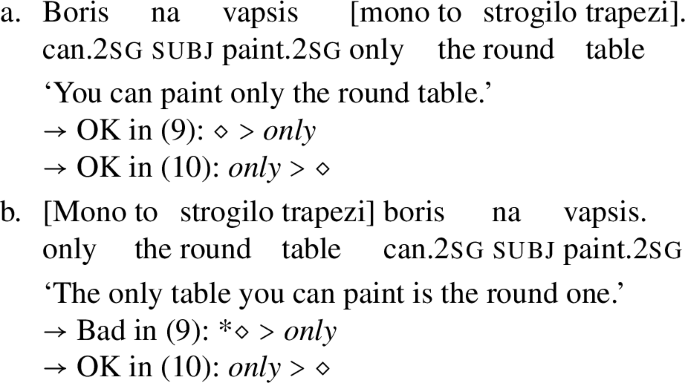

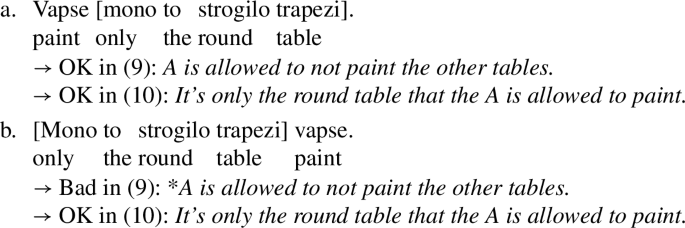

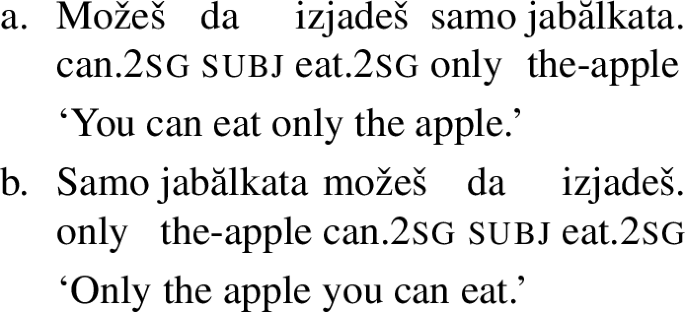

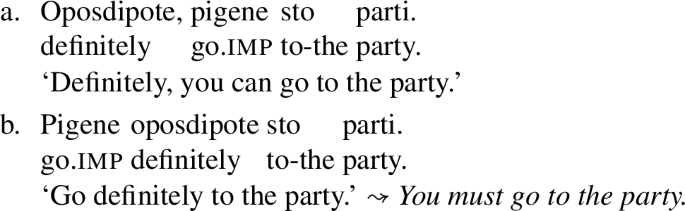

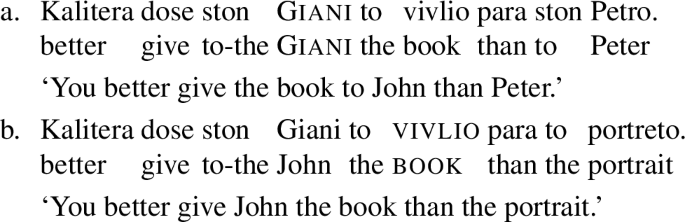

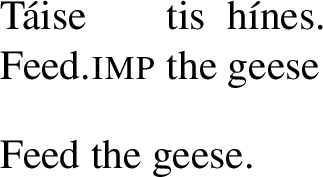

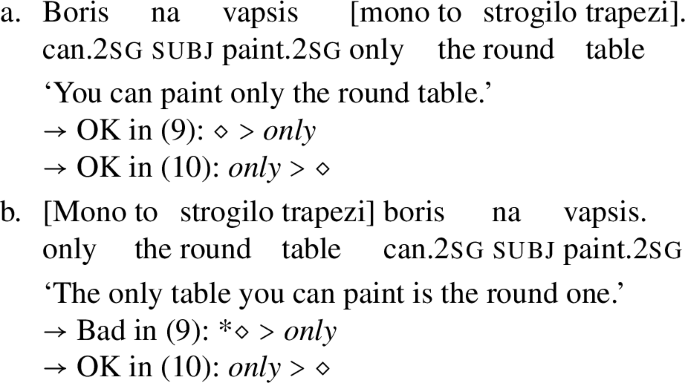

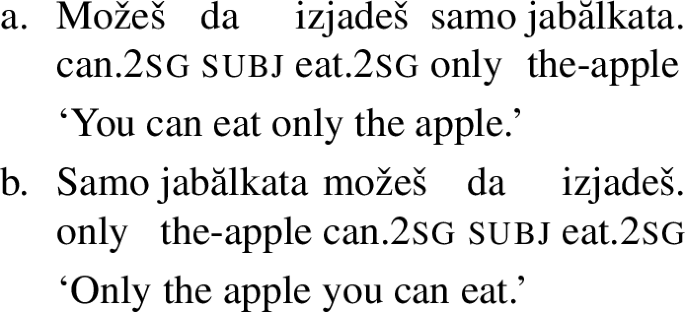

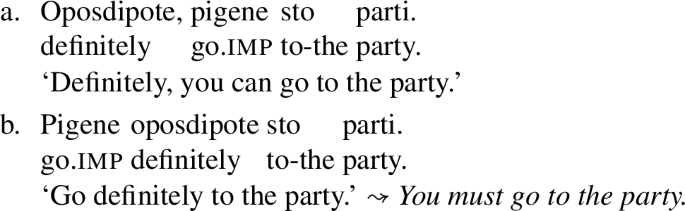

In Greek, the only-phrase can appear either in situ as in (11a) or fronted as in (11b). Fronting of the only-phrase resolves the scope ambiguity, in a way that it can only have a prohibitive interpretation, licensed as a response in (10, A). In what follows, I show that, when there is fronting, the imperative patterns with sentences involving an overt existential modal and not an overt necessity modal.

-

(11)

First I show that focus movement of the only-phrase above an overt modal operator in Greek, resolves the scope ambiguity, leading to a wide-scope interpretation of only (for a general discussion of focus movement in Greek see Tsimpli 1995; Baltazani 2002; Gryllia 2009).Footnote 2 I present scope resolution with an existential and a universal modal and I show that imperatives pattern with the existential modal rather than with the universal modal. I conclude that the underlying operator in this case should be an existential and not a universal.

Consider first the interaction of only with the overt existential modal in Greek. When only appears with its associate in-situ (12a), the sentence is ambiguous and, therefore, it is felicitous in both dialogues. When the only-phrase is preverbal (12b) only the wide scope (only > can) survives and therefore the sentence is good only in the dialogue in (10). (12b) has a prohibitive interpretation, i.e. it can only mean that the only table that A is allowed to paint is the round one (i.e. it’s not OK to paint the other tables).

-

(12)

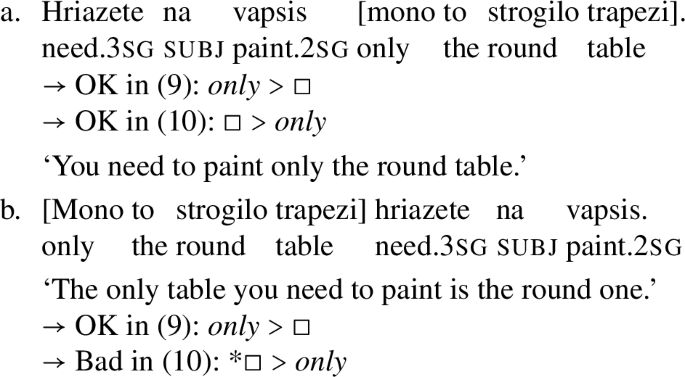

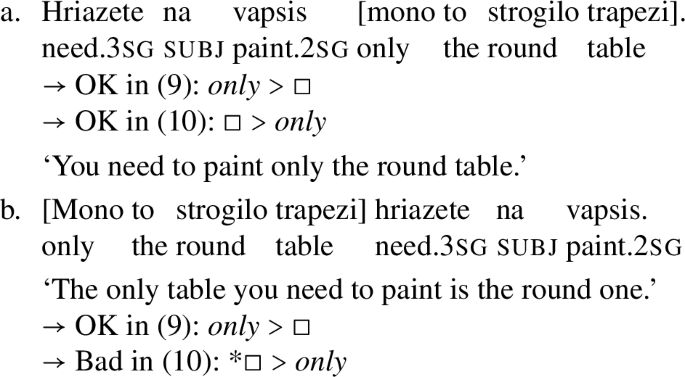

The same scope pattern is observed with the universal modal hriazete ‘need.’ When the only-phrase is in-situ as in (13a), both interpretations are available whereas when the only-phrase moves in front of the modal as in (13b) the most favored interpretation is that it is only the round table that is required to be painted. Notice that (13b) does not fit as a response to A’s sentence in (10) as it presupposes that the round table needs to be painted, which does not seem to be derived from what A says. (13b) would be a better response to A’s sentence in (9) suggesting a compromising solution.Footnote 3

-

(13)

Crucially, the imperative operator interacts with only in the exact same way that an existential modal does. In (14a), when the only-DP remains in situ, both the narrow-scope (imp > only) and the wide-scope (only > imp) reading is available. This is shown by the fact that (14a), just like its English counterpart, is good under both dialogues in (9–10). On the contrary, (14b), in which the only-DP undergoes focus movement, is felicitous only in (10) yielding a prohibitive interpretation that A is not allowed to paint the other tables. This indicates that the underlying operator in imperatives is a possibility and not a necessity modal.

-

(14)

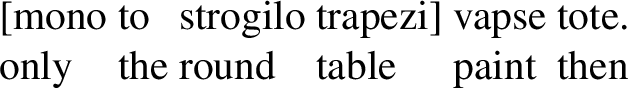

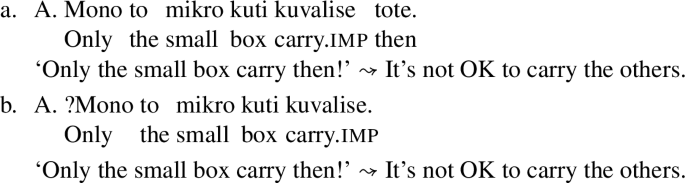

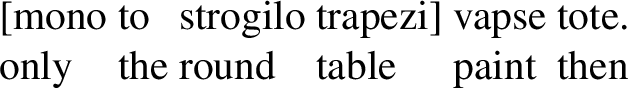

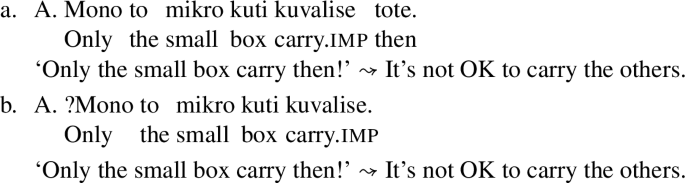

The data in (14) requires a bit more discussion. One reviewer points out that the facts with an imperative are not as clear as with the case of an overt modal. In particular the reviewer reports two groups of speakers, one group which indeed does not accept (14b) in a permissive context (e.g., (9)) as shown above, and one group which accepts (14b) even in a permissive context. In order to further investigate this hypothesis, I piloted a small study, in which speakers had to rate how natural they find the two variants (in a scale from 0 to 100) in a prohibitive and a permissive context. In addition, I elicited qualitative judgments from 6 native speakers (2 linguists and 4 non-linguists). 27 native speakers participated in the on-line study, and were shown four pairs of imperatives (with fronted and in-situ only) in a prohibitive context and six pairs of imperatives in a permissive context. Overall, sentences with a fronted only-phrase received a lower rating. Crucially, however, the mean naturalness rating was lower in the permissive (56.69%) than in the prohibitive context (82.37%) (see Appendix A). The fact that the speakers, in permissive contexts, rate the sentence with the fronted-only with an average 56.69% on the naturalness scale, shows, on the one hand, that they do not consider it very natural, but on the other hand, they do not evaluate the sentence as entirely unnatural in a permissive context. The responses from the qualitative study with 6 speakers shows that an imperative with fronted only becomes more acceptable in a context such as (9), if the person who utters the imperative sympathizes or accepts the objections of the addressee and prohibits them from doing more than they are willing to do. Thus, one possibility is that for some speakers the sentence retains its prohibitive meaning, as predicted by the current analysis, due to the speaker’s willingness to adopt the point of view of the addressee. This view is consistent with the observation by an anonymous reviewer, that these sentences become much better once we add the adverbial tote ‘then’ as in (15).

-

(15)

Tote ‘then’ refers to the objections raised by the addressee and signals that the speaker is willing to update his priorities given the new evidence. In this particular case, the speaker acknowledges the addressee’s difficult situation, and therefore only allows him to paint the round table. i.e. the sentence still induces a prohibition against painting the other tables. This function of tote ‘then’ becomes even more obvious in examples like the following in which the addressee explains that (s)he has a health issue. (16a) is quite natural with the interpretation that, given the addressee’s situation, the speaker does not allow him/her to carry more boxes. I find (16b) less plausible. However I can see how speakers can accommodate a covert tote ‘then’ and accept it in the given context.

-

(16)

A. We need to carry these boxes today.

B. Oh I have a terrible back-pain today...

An additional possibility, given the variation observed among participants (see the discussion in Appendix A), is that for some speakers there is no effect depending on the position of the only-phrase. This type of participant variation for scope judgements is a well attested phenomenon (see Oikonomou et al. 2020). Overall, based on the data presented in Appendix A and the qualitative judgements from native speakers we can say that when there is an effect of movement it goes in the direction expected by the current analysis. For the variation observed we need to further test the role of prosody among other factors.

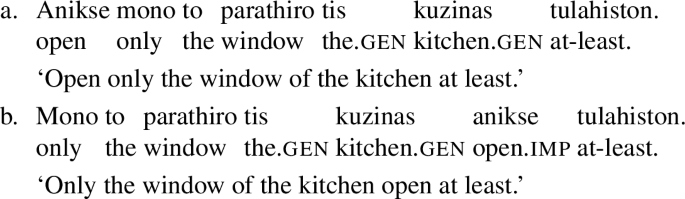

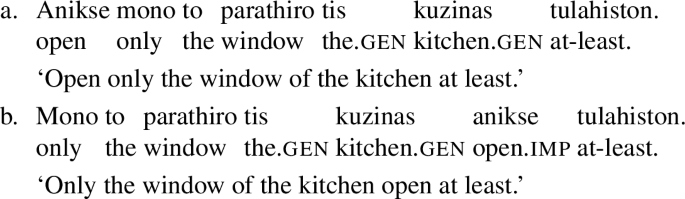

Finally, a reviewer also suggests that the sentences with fronted only can improve in the given permissive contexts if a different particle like tulahiston ‘at least’ or esto (concessive ‘even’) is added (for the at least-interpretation of esto in Greek see Giannakidou 2007). As the reviewer points out these particles clearly indicate a permissive context and, unlike tote ‘then’, they cannot be used to express prohibition. In order to test whether these particles are acceptable with the fronted only in permissive contexts I included three examples in the on-line study, two involving tulahiston and one with esto. In all of these cases the speakers rated the sentences with less than 50% in the naturalness scale which suggests that these particles are not consistent with a fronted only. For example, an imperative with fronted only and tulahiston ‘at least’ as in (17b) received mean rating 44.03% while the corresponding sentence with the in-situ only received mean rating 87.48% on a scale from 0 (=entirely unnatural) to 100 (=entirely natural).

-

(17)

The details of the study are discussed in Appendix A. While the results are to be interpreted cautiously, they do indicate that there is indeed a contrast between fronted and non-fronted only in permissive and prohibitive contexts. In addition, they suggest that, when there is an adverbial ensuring a permissive interpretation, the contrast becomes even stronger. While more research is necessary to corroborate the abovemade observation that fronting in only-sentences resolves scope ambiguity, some speaker variation is to be expected as it is usually the case with scope judgements in general.

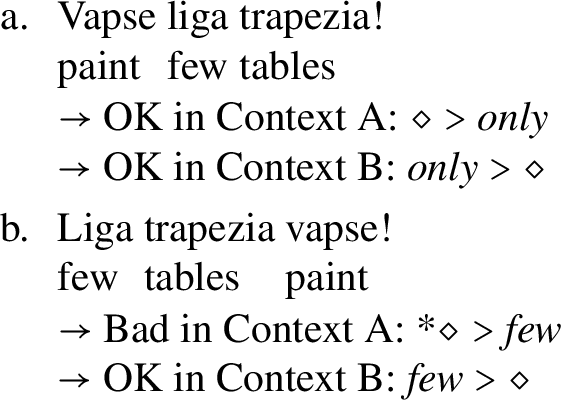

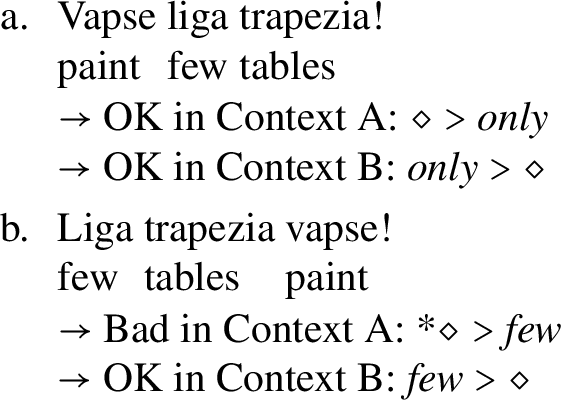

It is worth noticing that the scope ambiguity is not specific to the interaction with only, it is also attested with degree quantifiers such as few, fewer than.Footnote 4 (18a) in which few surfaces in-situ is felicitous in both Contexts A and B, whereas (18b), in which few has undergone overt movement, is only compatible with Context B. When few is interpreted below imp, the interpretation is that A is allowed to paint few tables (and it is OK to not paint all of them) whereas when few takes wide scope the interpretation is that there are few tables that A is allowed to paint (the rest of them he is not allowed to paint):

-

(18)

Before presenting how we can derive the scope ambiguity, I present in the next section data from Hungarian and Serbian which exhibit the same pattern.

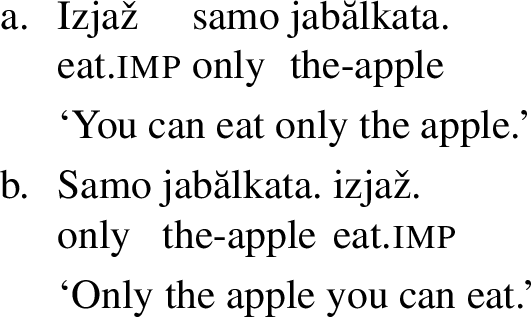

3.1.2 Scope facts in imperatives cross-linguistically

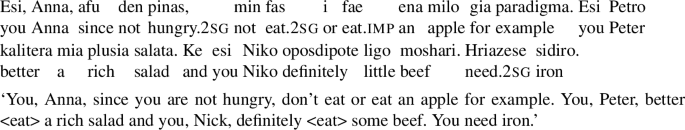

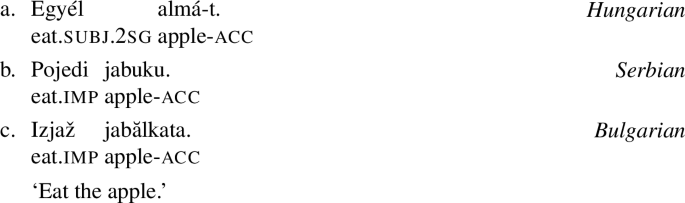

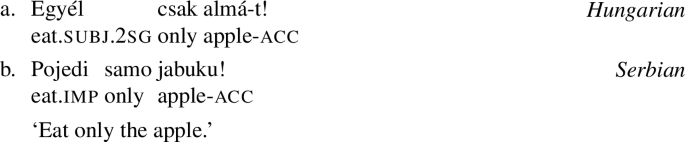

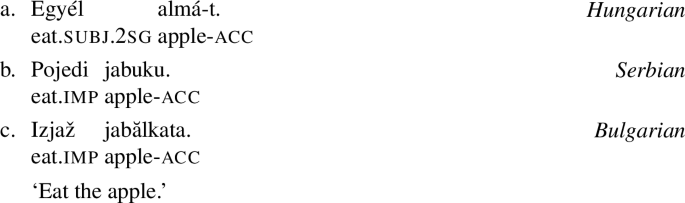

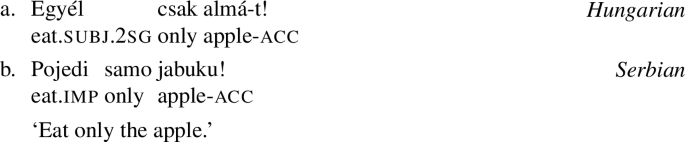

As a reviewer points out, one question is whether the scope facts with only can be replicated in other languages. In order to test this, it is necessary to look into languages which have overt focus movement with the particle only and additionally an imperative form which can have acquiescence interpretation. I was able to elicit data from three such languages, Bulgarian, Hungarian and Serbian.Footnote 5 In all of these languages the imperative can have acquiescence interpretations providing permission or weak advice. In particular the plain imperatives in (19) can be uttered as permission, weak advice or as a command, strong advice:

-

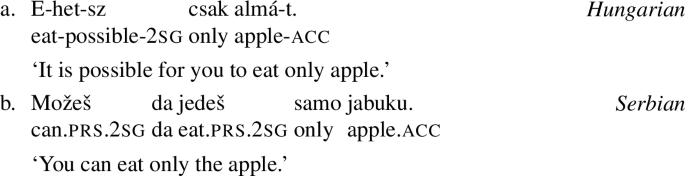

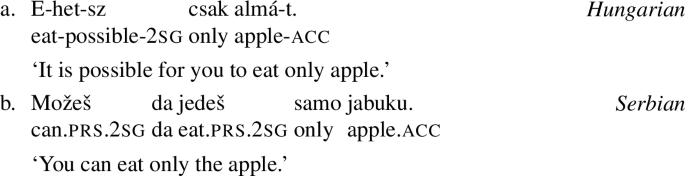

(19)

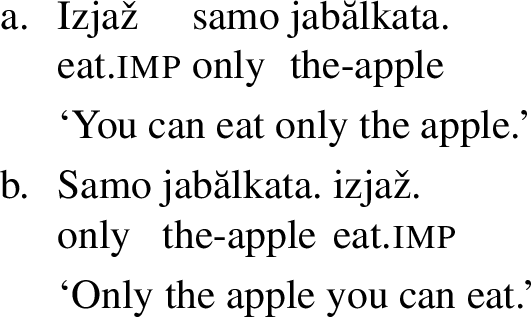

For the interaction of only with the imperative, the speakers in Hungarian (p.c. Éva Dékány) and Serbian (p.c. Ivona Ilić) reported the same pattern that I discuss for Greek in the previous section. The situation in Bulgarian seems to be less straightforward. One of the two speakers I consulted takes the effect of fronting with the overt modal but not with the imperative and for the other speaker fronting does not affect scope in either of the two cases. First, I present the facts for Hungarian and Serbian and then I discuss the Bulgarian data.

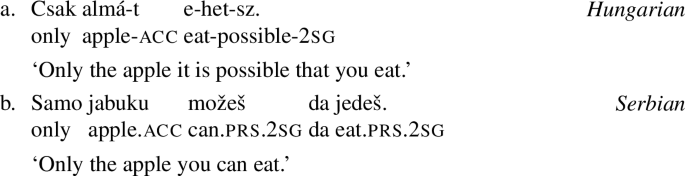

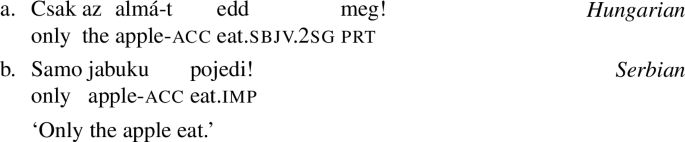

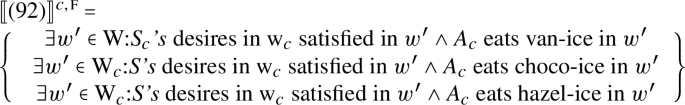

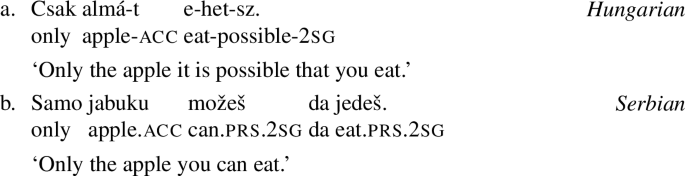

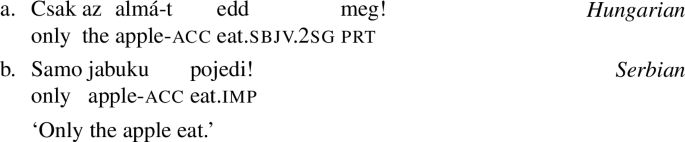

In both Hungarian and Serbian it is replicated that when the only-phrase moves above an overt possibility modal a prohibitive interpretation is derived for the relevant alternatives. This is shown in (21a) for Hungarian and in (21b) for Serbian. The sentence with the only-phrase in situ is consistent with an interpretation in which permission is provided to eat the apple and not eat other stuff. For example, the in-situ sentences in (20a) and (20b) are good in a context in which a child doesn’t like fruits, but his mom wants him to eat fruits, and in the end she compromises and says OK,“you can eat only the apple.” By contrast, the sentences with the fronted only-phrase in (21a–21b) are good only as prohibiting the alternatives, thus they cannot be uttered in the previous context. Instead, a context in which Mama is preparing a tart, and the child sees the fruits in the plate and he says “oooo I’ll eat the fruits!” makes the sentences with fronted only felicitous.

-

(20)

Permissive Interpretation:

-

(21)

Prohibitive Interpretation: ⇝ You are not allowed to eat other stuff.

In Hungarian and Serbian, the speakers report the same behavior for imperatives. The fronted only-phrase is licensed only in prohibitive contexts as the one with the tart, while the in-situ only can have a permissive interpretation:Footnote 6

-

(22)

Permissive Interpretation: → It’s OK to not eat the other stuff.

-

(23)

Prohibitive Interpretation: → You are not allowed to eat other stuff.

In Bulgarian, however, focus fronting does not have the same effect. According to Roumi Pancheva, focus fronting does indeed yield a prohibitive interpretation with the overt modal (24b) but not with the imperative (25b). That is, both variants in the imperative seem to be ambiguous. For Snejana Iovtcheva, focus fronting does not yield a prohibitive interpretation either with an overt modal or with an imperative.

-

(24)

-

(25)

The data in all languages require further exploration. For the lack of effect in Bulgarian, different possibilities arise. One possibility suggested by the reviewer is that there are two groups of speakers. A different possibility suggested to me by Snejana Iovtcheva is that in Bulgarian fronting of the only-phrase is not necessarily focus movement but can also illustrate a topic dislocation, which would then allow a strengthened interpretation of the imperative. Further investigation into the cross-linguistic patterns is necessary. However, the common behavior of Greek, Hungarian and Serbian lends support to the current hypothesis. The fact that we do not find the opposite pattern, i.e. imperatives patterning with necessity modals under focus fronting, is suggestive.

In what follows, I show how we can derive the observed pattern assuming that the imperative operator has existential force. Assuming universal force derives the wrong meaning in the case of overt movement. If there is no operator at all, it becomes impossible to account for the scope interaction with overt movement.

3.1.3 Deriving the scope ambiguity

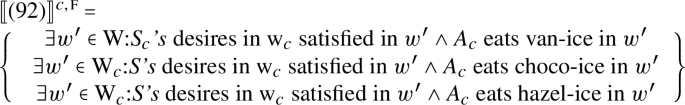

For the purposes of the discussion here, I follow a version of Horn’s (1969) analysis of only as a presupposition trigger; only takes as its argument a proposition p, presupposes that p is true and asserts the negation of all alternatives of p. Following Rooth (1992), the alternatives of p are computed by substituting the focused constituent round with the relevant alternatives in (9–10) (i.e. square/triangle). Let us assume that imp functions as an existential modal operator which takes as its argument a proposition from worlds to truth values deriving the meaning in (26) that there is a possible world \(\mathit{w}^{\prime}\) in which the speaker’s desires are satisfied and the prejacent is true in \(\mathit{w}^{\prime}\).Footnote 7

-

(26)

\([\!\![\textit{Open the window}]\!\!]^{w,c} = \exists{w^{\prime}}\) ∈ W. Sc’s desires in w are satisfied in w′ ∧ Ac opens the window in w′

Later on I will propose a decomposition of the imperative operator (imp) into two components: i) imperative mood restricting the worlds of evaluation and, ii) an existential operator which binds the open world variable. However, this decomposition of imp does not affect the line of argument here. The main explanation relies on whether the only-phrase is interpreted above or below imp. In particular, for our original example in (14), if only is interpreted above imp and imp has existential force, then we expect a prohibitive interpretation for the alternatives, since they are negated under Horn’s (1969) analysis (not allowed to paint round/square table). By contrast, if the only-phrase is interpreted below imp, then we expect a permissive interpretation that the addressee is allowed to not paint the rest of the tables.

The two patterns are shown below. When only has narrow scope, it attaches to the prejacent (below imp) yielding the LF in (27a) and the corresponding alternatives (A paints the round/square/triangle table). When only has wide-scope, it merges above imp, deriving the LF in (27b) and the alternatives that \(\exists{w^{\prime}}\) ∈ W. S’s desires in w are satisfied in w′ ∧ A paints the round/square/triangle table in w′:

-

(27)

-

a.

LF(\(\diamond _{imp}\) > only): [\(\diamond _{imp}\) [[only(C) roundF table ] [λx [you paint x]]]]

-

b.

LF(only > \(\diamond _{imp}\)): [only(C) roundF table] [λx [\(\diamond _{imp}\) [you paint x]]]

-

a.

Based on this, when only is interpreted below imp, we get the meaning in (28a) that there is a world consistent with S’s desires and A doesn’t paint the square/triangle table in this world. When only takes scope above imp, we get the interpretation in (28b) that there is no world consistent with S’s desires in which A paints the square/triangle table:

-

(28)

-

a.

\(\exists{w^{\prime}}\) ∈ W. S’s desires in w are satisfied in w′ ∧ ¬ [A paints the sqr/trg table in w′]

→ A is allowed to not paint the other tables.

-

b.

¬ \(\exists{w^{\prime}}\) ∈ W. S’s desires in w are satisfied in w′ ∧ A paints the sqr/trg table in w′

→ A is not allowed to paint the other tables.

-

a.

The data from Greek show that when the only-DP overtly moves, we get a wide scope reading. The interpretation of wide-scope only in imperatives reveals an existential operator. In the following section, it is shown that assuming a universal operator makes it hard to account for the case in which the only-phrase moves overtly.

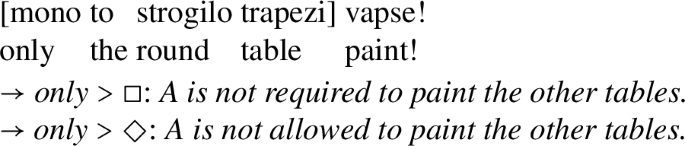

3.1.4 Scope facts under a universal analysis of imp

Under a universal analysis of the imperative operator, we can derive the expected interpretation for the examples in which only is in-situ, but we derive the wrong reading for the examples in which only-DP moves overtly. With a universal modal, when only is in-situ, two interpretations are derived. The surface scope interpretation is that the addressee is required to not paint the other tables, which fits the dialogue in (10). The inverse scope interpretation in which only scopes above the universal modal would be that there is no requirement for the addressee to paint the other tables which fits the dialogue in (9).

-

(29)

However, when the only-phrase moves, only the wide scope reading (only > □) is expected to survive. This interpretation is infelicitous as a response to A’s utternace in (10) (Oh, I feel like doing something really useful today. I think I’ll paint the tables over there.), because it conveys that A is not required to paint the other tables, whereas the desired interpretation is that A is required to not paint the other tables.

If we assume an ambiguous analysis of imperatives, argued by Grosz (2011), we would expect two possible readings for the example with overt focus movement:

-

(30)

The absence of the reading in which only has wide scope above a universal modal suggests that the imperative operator must bear existential force. Unless there is some mysterious condition under which overt movement blocks the universal reading, it is difficult to explain the interpretation of (30) assuming an ambiguity analysis.

3.1.5 Scope facts under a minimal approach

Assuming that there is no operator in the semantics, it is not possible to explain the facts as a scope ambiguity. Haida and Repp (2012) attempt to explain the ambiguity of the English data, not as a scope ambiguity, but as an ambiguity which arises by the imperative being interpreted as command or permission. However, the Greek overt movement data show that the ambiguity is scopal in nature.

One solution would be to postulate a speech act operator (as in Han’s 1998 analysis and unlike Portner’s 2004 proposal). In this case however, it is under question whether only could scope as high as a speech act operator (see Krifka 2001; Iatridou and Tatevosov 2016). A different alternative, suggested by a reviewer, would be to postulate a mapping rule between word order and interpretation but in this case, we could not explain why fronting has the same effect with overt existential modals.

In what follows, I present two more environments which reveal the existential character of imperatives: interaction with the scalar particle akomi ke ‘even’ and Free Choice licensing.

3.2 Imperatives and akomi ke ‘even’

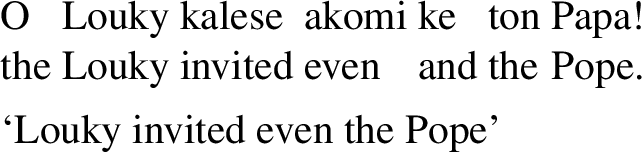

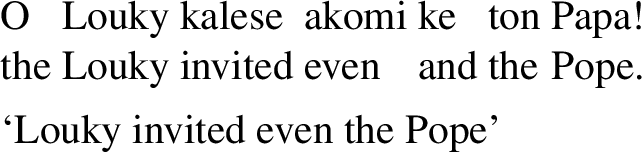

Additional evidence for the existential character of the imperative comes from the licensing of the Greek scalar additive particle akomi ke ‘even.’ Below, I show that the licensing requirements for akomi ke are such that in some cases its compatibility with an imperative reveals the presence of an existential operator.

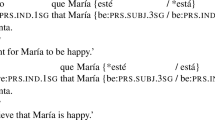

Akomi ke can be analysed, similarly to even, as a propositional operator which gives rise to two presuppositions; it presupposes that i) the proposition is less likely than its alternatives (scalar presupposition) and ii) that some proposition from the contextual alternatives is also true (additive presupposition) (see Giannakidou 2007; Barouni 2018). For example, for a sentence like (31) we get two presuppositions as in (32):

-

(31)

-

(32)

-

a.

Scalar presupposition: The Pope is the least likely to be invited by Louky.

-

b.

Additive presupposition: Someone else other than the Pope has been invited by Louky.

-

a.

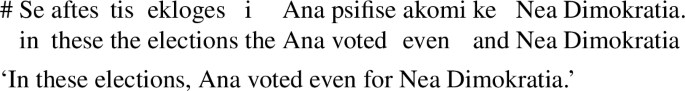

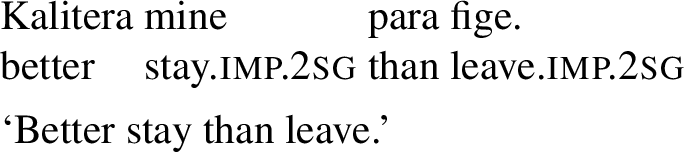

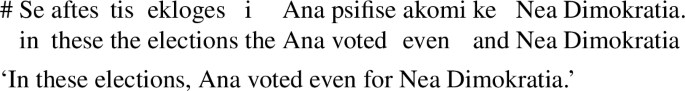

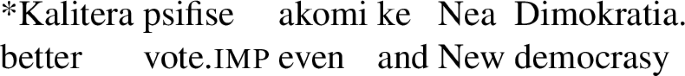

Crucially, akomi ke is not licensed with predicates like vote in episodic contexts. The additive presupposition cannot be satisfied because world knowledge tells us that we can vote only for one party. As a result the sentence in (33), like its English counterpart, is judged infelicitous by native speakers:

-

(33)

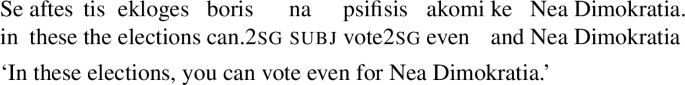

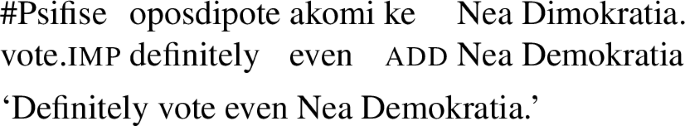

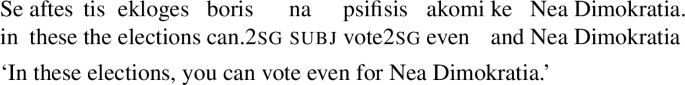

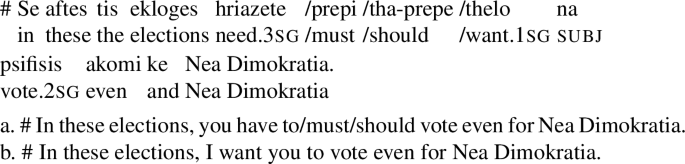

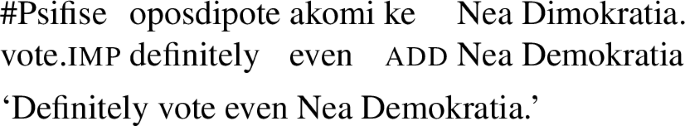

However, in the presence of an existential modal operator, the sentence becomes fine since the additive can take wide scope above the modal. Consider a context in which the speaker generally supports left-wing parties, but in this case there are some local elections of no importance. In this case the sentence in (34) expresses that it’s OK to vote for the right-wing party Nea Dimokratia, thus providing permission or consent.

-

(34)

Assuming that in this context the possibility modal boris ‘can’ provides permission and has a bouletic character (see Lauer 2015), the sentence conveys that:

-

(35)

-

a.

There is a possible world compatible with the speaker’s desires in which the addressee votes for Nea Dimokratia (assertion).

-

b.

Nea Dimokratia is the least likely party that there is a possible world compatible with the speaker’s desires in which the addressee votes for it (scalar presupposition).

-

c.

There is another party different from Nea Dimokratia such that there is a possible world compatible with the speaker’s desires in which the addressee votes for this party (e.g. a left-wing party) (additive presupposition).

-

a.

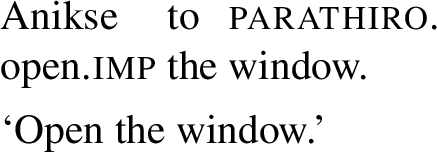

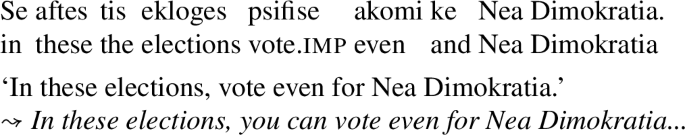

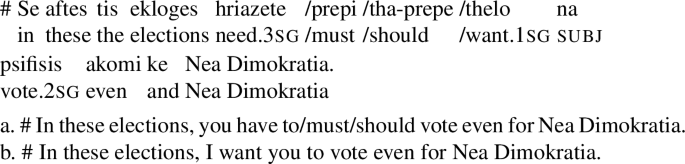

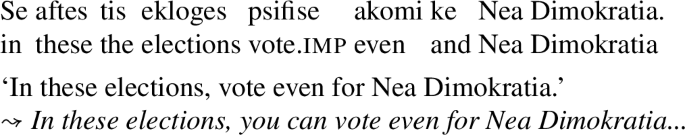

Crucially, we can have exactly the same interpretation in the same context with an imperative as shown in (36). This can only be explained if there is an operator above which akomi ke ‘even’ can take scope and also if this operator is a possibility modal operator.

Context: Mary generally supports the left-wing parties and she tries to convince people to vote for a left party. However, this time there are some local elections of no importance. In this context, she can utter the imperative in (36) conveying that it’s OK for her even if the addressee votes for the right wing party Nea Dimokratia:

-

(36)

These data converge with the evidence from the previous section, that imperatives involve an existential modal.

Notice that under a universal modal hypothesis the licensing of akomi ke ‘even’ is harder to explain. A universal modal operator is not licensed in this context. The modals hriazete, prepi, tha prepe and the bouletic attitude verb thelo ‘want’ do not license akomi ke ‘even’:Footnote 8

-

(37)

An ambiguity approach can also account for the licensing of akomi ke ‘even’ but as we saw in the previous section an ambiguity hypothesis is not supported by the scope facts with mono ‘only.’

English differs from Greek in the interaction of even with imperatives and the judgements for sentences like (36) vary among different speakers. For some speakers the translation in (36) is completely out and for others it is only marginally accepted.Footnote 9 Although, it is not clear to me what the source of difference is between English and Greek, there is independent evidence from the interaction of the imperative with even in English supporting the underlyingly existential character of imperatives.

Francis (2019) shows that when even associates with the prejacent proposition (broad focus even), the imperative must be interpreted as providing permission, i.e. it can only have a weak possibility modal interpretation. This is illustrated in (38–39). In (38), where the context foregrounds a command interpretation, a broad focus even yields infelicity, whereas in (39) it is perfectly fine with a permission-interpretation.

Context: Prof. X is invigilating an exam and orders the students to stop writing.

-

(38)

Put down your pens. [Close your exam papers]F #even.

Context: Prof. Y is telling students who have been writing an exam that the test will no longer count toward their grades and they are free to do whatever they like.

-

(39)

Francis (2019) builds on a version of the current proposal, analysing imperatives as involving an existential modal which can be strengthened to convey necessity by exhaustifying over the alternatives. When even takes wide scope over the entire proposition, it predicts an additive presupposition for the prejacent and the alternatives. In this case it is presupposed that the addressees are simultaneously required to close and not close their papers. Thus, Francis (2019) derives the infelicity of broad focus even with imperatives as one of additive presupposition.

These data cannot be tested in Greek, as Greek akomi ke cannot take broad focus based on judgements from six speakers who I have consulted on Greek akomi ke.

Despite the differences between the Greek and English additive scalar particles, evidence converges with the conclusion derived in the previous section regarding the interaction of the exhaustive particle mono ‘only’ with imperatives. These facts present evidence for the presence of an operator in the semantics (otherwise scope interactions are difficult to explain) which must be existential in nature. Further evidence comes from Free Choice Items (FCIs) with imperatives both in English and Greek.

3.3 FCIs and imperatives

As it is well-discussed, imperatives license Free Choice Items (FCIs) (Schwager 2006; Aloni 2007; Kaufmann 2012; a.o.):

-

(40)

-

a.

Pick any flower!

-

b.

Read any book!

-

a.

Given that unmodified FCIs are licensed with existential (41) but not with universal (42) modals, the compatibility of FCIs with imperatives can be taken as a supporting argument in favor of an existential analysis and against a universal analysis of imperatives.

-

(41)

-

a.

You may pick any flower!

-

b.

You may read any book!

-

a.

-

(42)

-

a.

*You must/should pick any flower!

-

b.

*You must/should read any book!

-

a.

However, such a conclusion is disputed in the literature (Han 2000; Kaufmann 2012), arguing that the data are more complex, supporting the universal approach. I briefly discuss their points showing that the first impression that imperatives behave as involving an existential modal in these contexts, is the right one.

Kaufmann (2012) argues that an imperative involving a FCI is not in fact interpreted as the corresponding sentence with an overt existential modal. In particular, she analyses an example like (40a) as having the interpretation that the addressee must pick a flower and that the speaker is indifferent as to which flower the addressee will pick (e.g. you must pick a flower but I don’t care which).

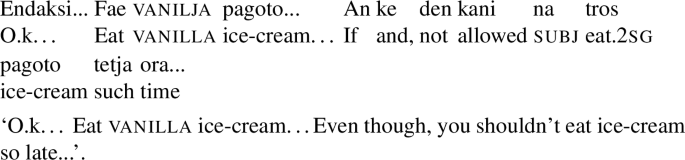

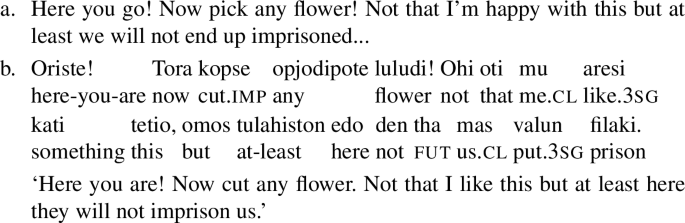

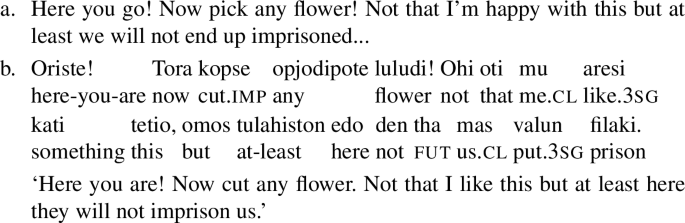

However, this intuition is contradicted by the following examples where the continuation clearly indicates that the prejacent of the imperative is not taken to be a requirement by the speaker:

Context: A mother and her five-year-old son are visiting the botanical garden ‘Jardin des plantes’ in Paris. Her son, who aspires to become a gardener, wants to cut some rare lilies to plant in his small garden. His mom, manages to convince him not to but he stays grumpy the entire time. When they arrive at her sister’s place which has a small garden, his mom says:

-

(43)

In this example, it is clear that the parent imposes no obligation to the child to pick a flower and yet the FCI imperative is perfectly fine in this context.

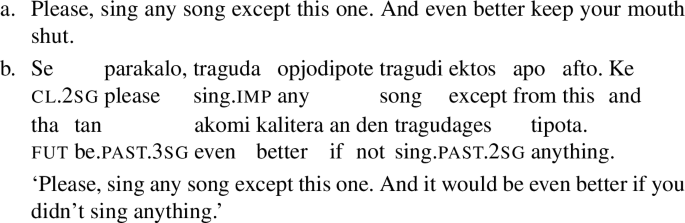

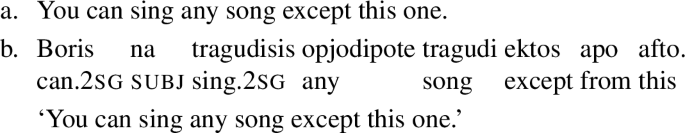

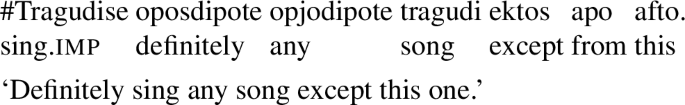

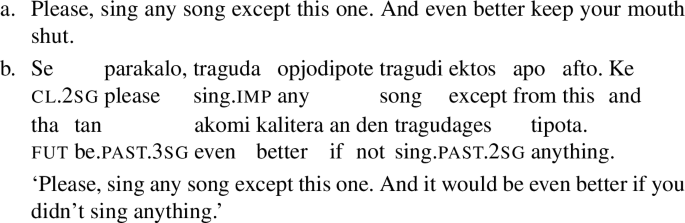

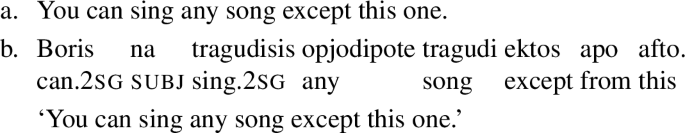

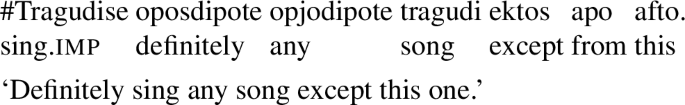

The existential character of the imperative becomes even clearer when a FCI combines with an exceptive as in (44). In this example, the speaker would prefer that the addressee doesn’t sing any song as the continuation suggests. The meaning that we get is that the addressee is allowed to sing any song except a particular one. It cannot mean that he is obliged to sing a song.

-

(44)

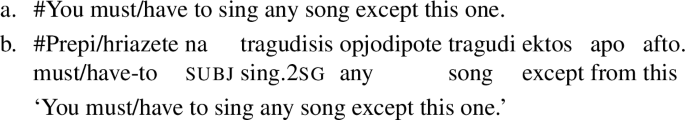

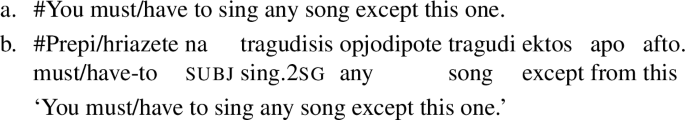

Notice that any sort of universal modal combined with an exceptive FCI sounds odd:Footnote 10

-

(45)

A possibility modal is, of course, compatible and the interpretation is very similar to the one we get with imperatives:

-

(46)

Free choice phenomena have received different analyses varying in the proposed force and the position of the FCI (see Chierchia 2013; Dayal 2013; Menendez-Benito 2005, 2010; a.o.). Under a common approach, FCIs have universal force (cf. Menendez-Benito 2010). Under this hypothesis, imperative sentences with FCIs can be analysed as involving a possibility modal operator which is in the scope of a universal quantifier. Giannakidou (2001), who analyses free choice items as indefinites, treats free choice imperatives as in (43) as involving a possibility operator. Assuming that imperatives involve a universal operator, it would be hard to account for FCI licensing. Notice, however, that these data can also be accounted for under an ambiguity analysis of imperatives.

Although we cannot do justice to the topic of Free Choice in imperatives in the scope of the present discussion, the data we saw suggest that the distribution of FCIs remains a good reason to doubt an all-universal analysis of imperatives (see Menendez-Benito 2005 for a similar argument in favor of an existential analysis of generic sentences).

3.4 Interim summary

In this section, I presented evidence from the interaction of imperatives with mono ‘only’ and akomi ke ‘even’ as well as from the distribution of FCIs in favor of the existential character of imperatives. The question arising is whether we can formulate an analysis which can capture these facts without ignoring the possible stronger meanings of imperatives.

Stronger imperatives come in two varieties: the first type involves plain imperatives which can express request, command or strong advice as we saw in (1). As will be shown in Sect. 6, this type can be derived from a primarily existential meaning. However, there is a second type of strong imperative which cannot be captured if we analyse imperatives as always involving an existential operator. These are cases in which the imperative combines with a modal adverb expressing necessity or graded modality, which are discussed in detail in the next section.

4 Imperatives combined with modal adverbs

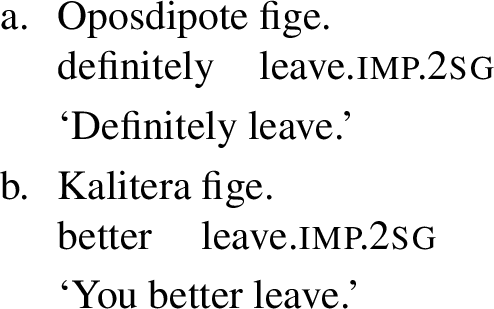

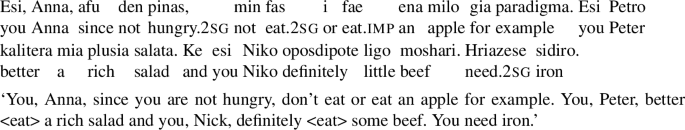

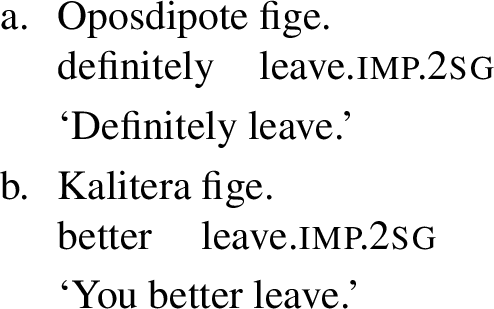

This section presents two types of imperatives whose force seems to be dependent on a specific adverbial. Imperatives in Greek can combine with an adverbial expressing universal force and derive an unambiguously strong (command) interpretation as in (47a) or with an adverbial encoding a comparative preference as in (47b).Footnote 11 The latter has also a counterpart in English, better:

-

(47)

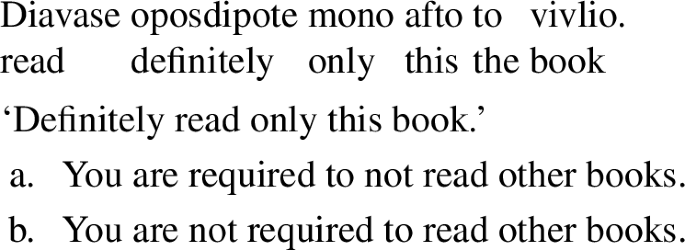

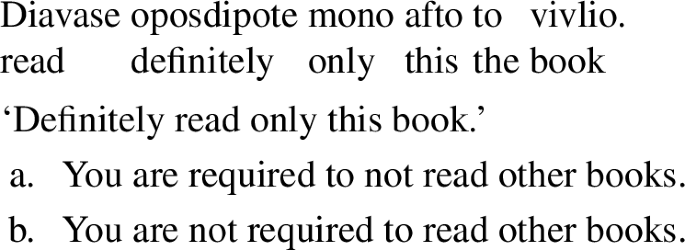

Interestingly, the interpretation of (47a) cannot be derived under an existential analysis whereas (47b) is not consistent with either an existential or a universal analysis. This is important because it suggests that we need to refine our analysis of imperatives in a way that the existential operator is not always present in imperatives. This will lead us to Sect. 5, which develops an analysis for the observed variation without resorting to polysemy.

In what follows, I present the properties of oposdipote- and kalitera-imperatives.

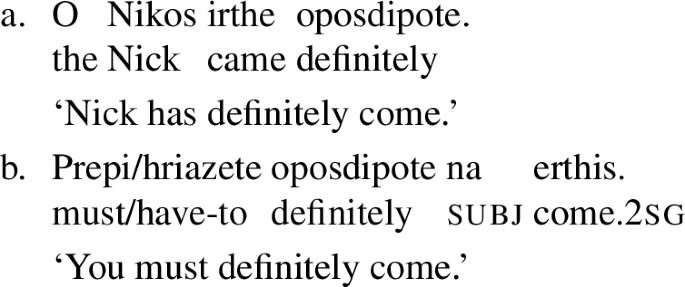

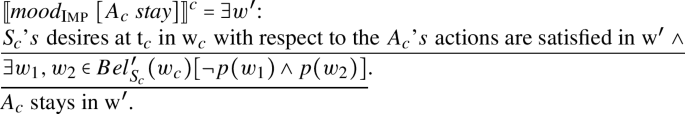

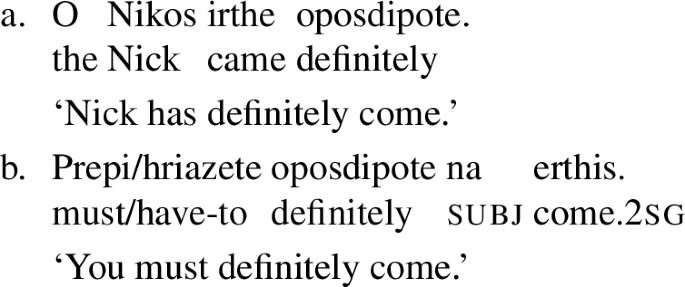

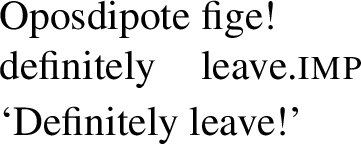

4.1 Oposdipote-imperatives

The adverbial oposdipote is generally used to express necessity and it is compatible both with epistemic and deontic/bouletic necessity as shown in (48a) and (48b) respectively.Footnote 12

-

(48)

When oposdipote is used with a possibility modal or even a weak necessity modal, the sentence is interpreted as involving two modal operators: a possibility or a weak necessity modal, and then on top of it, a necessity modal which, as shown in the following examples, expresses epistemic necessity. For example, the speaker given what he knows (e.g. that the work has finished, that nobody else is going to call) provides permission or reports that the addressee can leave. In this case, however, oposdipote must appear either in the beginning or in the end of the clause with an intonational break between oposdipote and the prejacent.

-

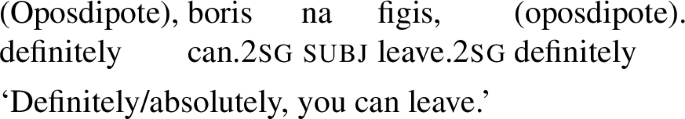

(49)

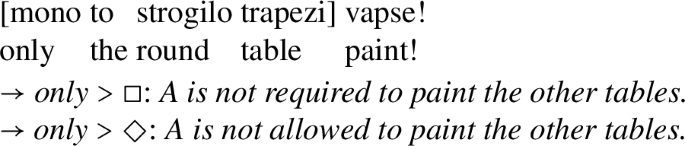

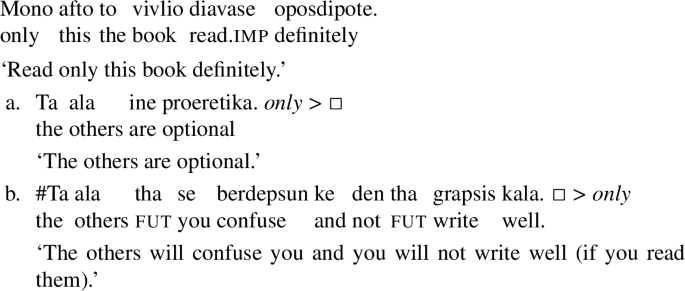

Similarly, if there is an intonational break between oposdipote and the imperative, it results in an epistemic necessity modal on top of the existential, as predicted by the hypothesis that imperatives involve an existential modal. In these cases, oposdipote has to either precede or follow the imperative proposition. However, when there is no intonational break or when the adverbial appears inside the clause (50b), the imperative is unambiguously interpreted as a command, i.e. inducing a requirement. This is illustrated by applying the same tests we used in Sect. 3 to argue in favor of the existential character of plain imperatives.

-

(50)

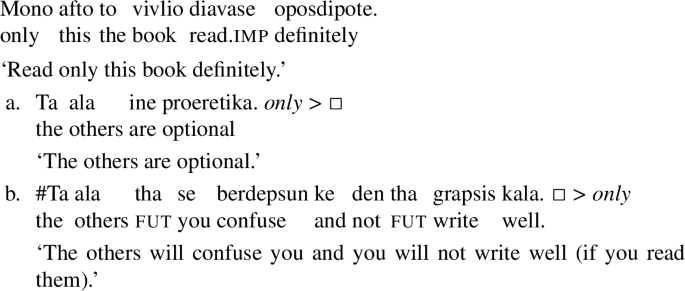

First, when we have both oposdipote and only in a sentence, we observe that when the only-phrase precedes the verb and oposdipote as in (51), we get an interpretation that for the other books it’s not necessary that A reads them. The compatibility of the continuation in (51a) as opposed to the continuation in (51b) shows that only here takes scope above a necessity modal:

-

(51)

When ‘only’ appears below the verb and oposdipote, the b-continuation becomes immediately felicitous, and the interpretation we get is that it’s necessary to read only this book and not read the other ones. In this case, however, when the only-phrase is in-situ the wide scope interpretation of only is also possible (especially with certain intonation) thus rendering the a-continuation of (51) felicitous as well.Footnote 13

-

(52)

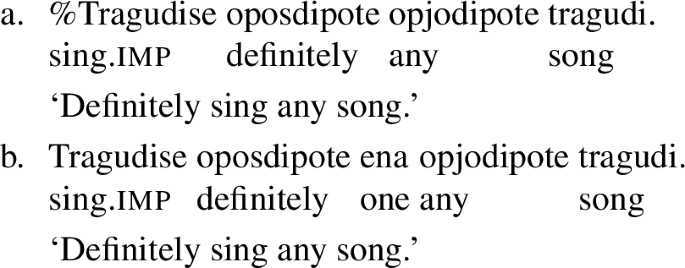

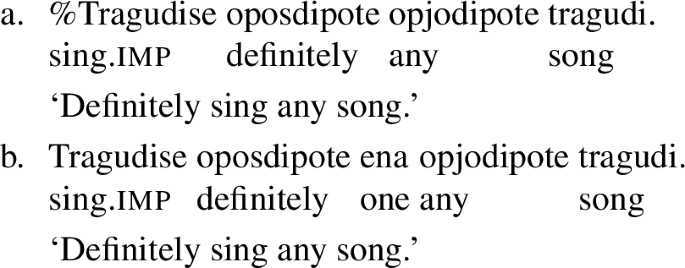

The necessity character of oposdipote-imperatives is also instantiated by the fact that they do not license FCIs as opposed to plain imperatives. To the extent that (53a) is felicitous, it is only under the reading of the existential FCI expressing indiscriminacy as discussed in detail in Vlachou (2007). This reading is better expressed with the indefinite ena as in (53b) (see also fn. 10).

-

(53)

Similarly, a FCI combined with an exceptive phrase is not felicitous with oposdipote:

-

(54)

Under all diagnostics oposdipote-imperatives pattern with universal modals. This is further shown by the fact that the scalar additive particle akomi ke is inconsistent with an oposdipote-imperative as in (55).

-

(55)

The only way to interpret (55) is to read it as having two sentences but in this case a long pause is necessary after oposdipote. As a reviewer points out, in this case the second sentence involving the scalar particle akomi ke will involve an elided imperative psifise ‘vote.’ Crucially, under the account I present in Sect. 5, we predict that the imperative in the second clause can express possibility because what is elided is of unspecified quantificational force (see fn. 15).

Having shown that imperatives which combine with oposdipote obligatorily get a necessity interpretation, we can now turn to the interpretation of imperatives which combine with kalitera ‘better.’

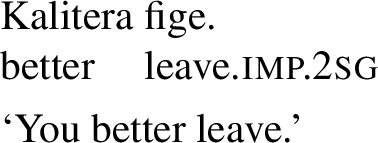

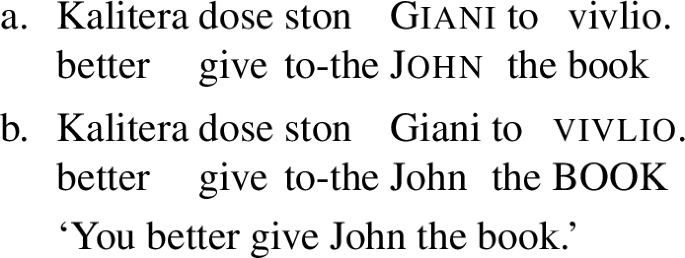

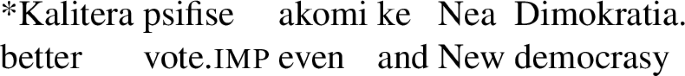

4.2 Kalitera/(better)-imperatives

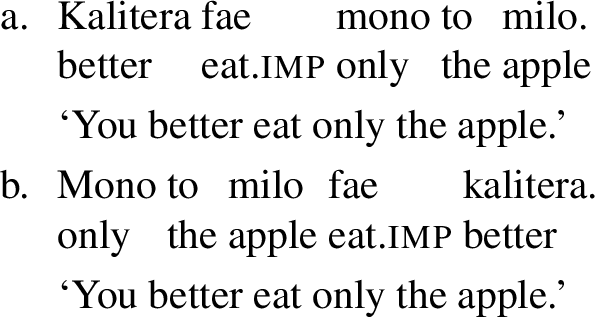

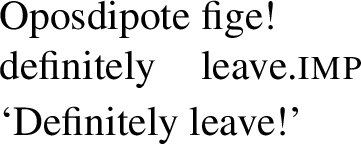

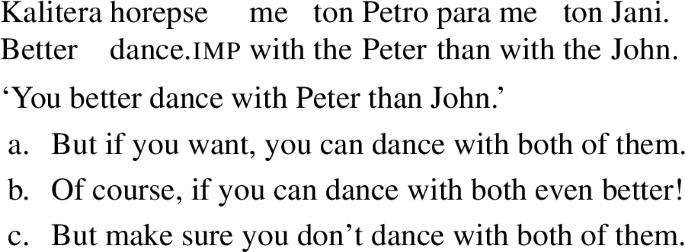

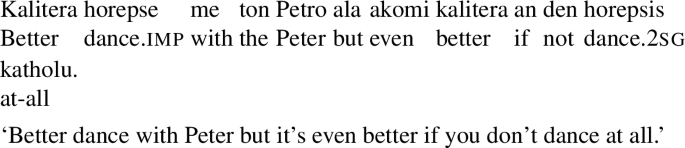

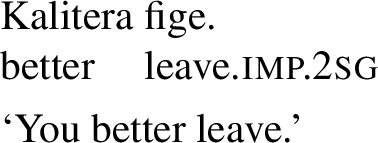

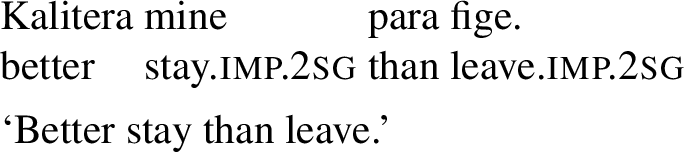

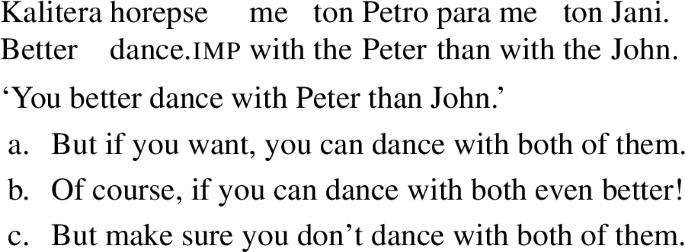

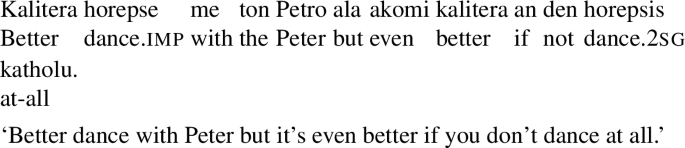

When kalitera ‘better’ combines with an imperative as it does in (56), it compares two alternatives and states that one is better than the other. In particular, we get the interpretation that the speaker believes that it’s better for the addressee to leave than stay.

-

(56)

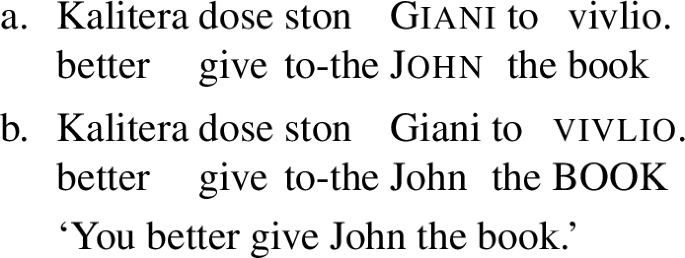

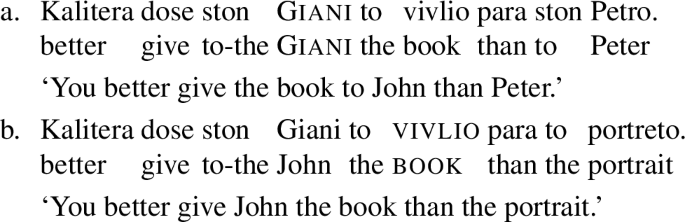

In more complex sentences we can see that the alternatives depend on focus alternatives. For example, in (57a) the indirect object is focused deriving alternatives of the form better give x the book whereas in (57b) the direct object is focused deriving alternatives of the form better give John x:

-

(57)

The alternative can also be overtly represented with a comparative than-phrase.

-

(58)

In Greek the overt alternative can often involve an imperative verb, suggesting that the complement to the than-phrase is also an imperative clause. This will be important when the internal structure of kalitera-imperatives is discussed in Sect. 5.4.

-

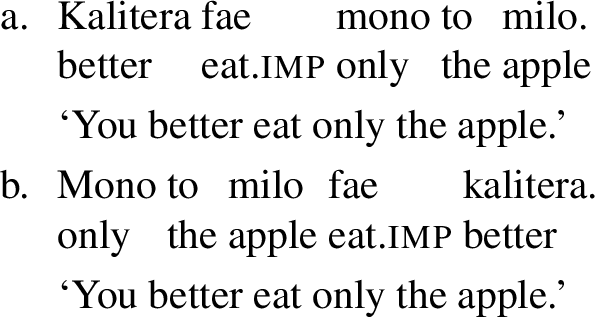

(59)

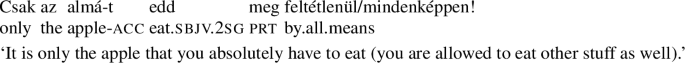

Kalitera-imperatives are different from plain imperatives as they cannot be used in permission/invitation contexts or in command/requests in which a plain imperative gets a strong interpretation. Moreover, the tests that we presented for the existential character of imperatives do not work for kalitera-imperatives. FCIs are not licensed and it is not possible for mono ‘only’ to scope above kalitera. Mono ‘only’ must be in the scope of kalitera ‘better’ as shown in (60). In both sentences kalitera is interpreted above only, yielding the interpretation that it is better to eat the apple and not eat something else.

-

(60)

Similarly, the scalar element akomi ke ‘even’ cannot scope above kalitera ‘better’ and generate a sensible interpretation, as illustrated in (61):

-

(61)

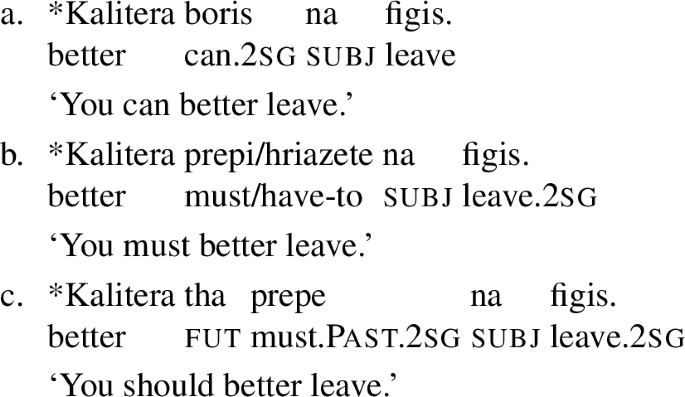

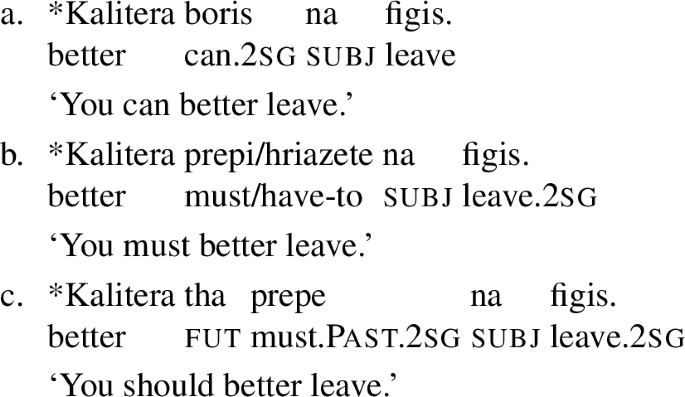

Kalitera ‘better’ is only licensed with imperatives and root subjunctives. It cannot combine with possibility (62a), necessity (62b) or weak necessity modals (62c). This is true for Greek and for English. Some English speakers marginally accept better with weak necessity modals but they still consider them degraded, using a different construction instead.Footnote 14

-

(62)

It is clear that we are dealing with three different creatures:

-

i.

Plain imperatives → Existential force

-

ii.

Oposdipote-imperatives → Universal force

-

iii.

Kalitera-imperatives → Comparative modality

This variability in meaning can be explained either assuming that imperatives are truly polysemous or under a unified analysis in which variation arises due to the presence of oposdipote and kalitera respectively.Footnote 15 In this paper, I endorse the latter option arguing that the imperative construction has a basic unified meaning which is enriched depending on the environment it appears in.

5 Imperatives are minimal but modalized

In this section, I develop an analysis in which the imperative form per se does not involve a modal operator. Instead, I suggest that the imperative form, at least in Greek and other languages with imperative morphology, corresponds to imperative verbal mood with a special [+imp]-feature (see Rivero and Terzi 1995 a.o.).Footnote 16 While [+imp]-mood carries certain presuppositions which enforce a modal interpretation, it does not contribute a special quantificational force. In this way, the complex facts we presented in the previous sections will be accounted for. On the one hand, the scope facts revealed an underlying possibility operator in imperatives while, on the other hand, in the presence of an overt quantificational operator imperatives acquire the force of this operator.

In what follows, I show that the underlying possibility meaning of an imperative like ‘Open the window’ in (26) repeated in (63), can be derived in two different steps.

-

(63)

\([\!\![\textit{Open the window}]\!\!]^{c} = \exists{w^{\prime}}\) ∈ W. Sc’s desires in wc are satisfied in w′ ∧ Ac opens the window in w′

First, it is necessary to consider the internal make-up of an imperative clause. Suppose that the imperative form only involves a mood-Phrase with an imperative feature as in (64):

-

(64)

[\(_{MoodP}\) Mood\(_{\textsc{Imp}}\) [\(_{TP}\) T [\(_{VP}\) ...]]]

The meaning derived at the level of MoodP is the propositional content plus whatever the semantic contribution of Mood\(_{\textsc{Imp}}\) is. Our next task is to define the role of imperative mood (Mood\(_{\textsc{imp}}\)) which is critical for the derivation of the imperative meaning. For this, I introduce some necessary background on verbal mood.

5.1 Background on verbal mood

Verbal mood is usually discussed in relation to the distribution of indicative vs. subjunctive in embedded contexts. In most cases, imperative verbal mood is either not discussed at all, or it is taken to be the verbal mood of the imperative sentence mood. It is not possible within the scope of this paper to review all previous theories of verbal mood (Farkas 1992b, 2003; Portner 1997, 2011, 2018b; Schlenker 2005; Quer 2009; Portner and Rubinstein 2012; Giannakidou 2015; Silk 2018). There are good reasons to think that imperative mood shares many features with subjunctive (as opposed to indicative); however in this paper I will not get into their relation (see e.g. Huntley 1984; Portner 1997, 2015; Oikonomou 2016; Stegovec 2016). Instead, I focus solely on the imperative.

There are various ways in which the contribution of verbal mood has been described. A fruitful way put forth in various works with different perspectives (Portner 1997; Schlenker 2005; Matthewson 2010; Silk 2018) is to think of verbal mood as involving a feature which triggers a presuppositional restriction. The analysis of imperative mood developed here largely builds on Schlenker’s view of mood as introducing a presupposition on world-denoting variables (Schlenker 2005: 1).

5.1.1 Schlenker’s (2005) analysis of mood

Schlenker (2005) builds on the idea that mood can be analyzed on a par with tense and pronouns (see Stone 1997; Iatridou 2000; von Stechow 2002 for earlier parallelisms of this sort) as presuppositions on the value of certain terms or variables. Within this framework, he analyses indicative mood as carrying a marked feature triggering a presupposition that a proposition marked with indicative denotes a world that lies in the Context Set of the speech act. The notion of Context Set is introduced from Stalnaker (1975) and it refers to the set of the worlds which are compatible with what the speaker presupposes. Schlenker (2005) also argues that the subjunctive in French is the default, and therefore does not trigger a presupposition. As I said, we are not going to discuss the indicative-subjunctive debate in this paper (see Portner and Rubinstein 2012 for an overview and some problems with Schlenker’s (2005) analysis of indicative mood). What is rather interesting for our purposes is Schlenker’s rather short and rough account of the contribution of imperative mood.

According to Schlenker (2005) imperative mood introduces a presupposition on the value of a term w indicating that the term w denotes a world which is compatible with what the speaker requires at the time and in the world of utterance (Schlenker 2005: 12).

In addition, he assumes that there is a covert operator in imperatives roughly meaning I (=speaker) require that p. Under this view, the meaning of an imperative clause with the contribution of the presupposition is that each world compatible with what the speaker requires at the time and in the world of utterance is compatible with... what the speaker requires at the time and in the world of utterance. As Schlenker (2005) points out this is vacuously true but the presupposition is satisfied.Footnote 17

For the rest of this section, I invite you to consider what would happen if there is no covert operator in the first place as part of the imperative clause, and instead we only have a presupposition triggered by the imperative mood, similar to the one suggested by Schlenker (2005).

5.2 Imperative mood as triggering a presupposition

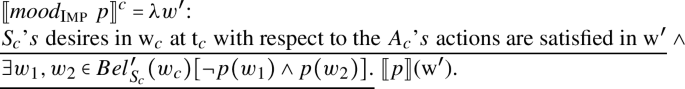

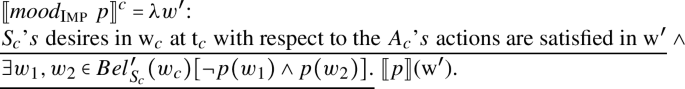

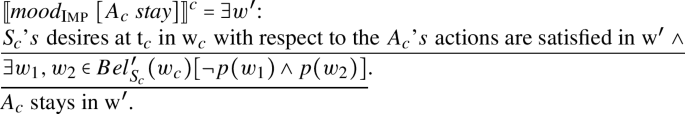

In many works, special imperative morphology has been associated with imperative verbal mood which carries a special [+imp] mood feature. Following Schlenker’s (2005) insight, I argue that imperative mood triggers a presupposition restricting the reference of the world term w. In particular, imperative mood restricts the reference of the world term to worlds consistent with what the speaker desires at the utterance context c, which is defined by a quadruple containing a speaker Sc, an addressee Ac, a time tc and a world wc:

-

(65)

\([\!\![\textit{mood}_{\textsc{Imp}}]\!\!]^{c} = \lambda \)p ∈ D\(_{\langle{\mathit{st}}\rangle}\). \(\lambda{w^{\prime}}\): Sc’s desires in wc at tc with respect to the Ac’s actions are satisfied in w′. p(w′) = 1

Mood\(_{\textsc{Imp}}\) is then a propositional operator which contributes only a presupposition. The meaning we derive now at the level of mood\(_{\textsc{Imp}}\)P is a partial function from worlds to truth values:

-

(66)

\([\!\![\textit{mood}_{\textsc{Imp}}\ p]\!\!]^{c} = \lambda{w^{\prime}}\): Sc’s desires in wc at tc with respect to the Ac’s actions are satisfied in w′. 〚p〛(w′).

Now at the level of mood\(_{\textsc{Imp}}\) there are different possibilities for the interpretation of the world term. One of these possibilities is for the world variable to be restricted by the world of the utterance context c, which is usually the actual world. This would mean that it is presupposed that the speaker’s desires are satisfied in the actual world and the prejacent holds in the actual world. However, we want to exclude this reading because as we know imperatives cannot express statements about the actual world. To illustrate, consider the contrast in (67):

-

(67)

-

a.

#Stay! I know you will.

-

b.

I want you to stay and I know you will stay.

-

a.

On the contrary, the speaker needs to encounter both the prejacent and its negation to be viable possibilities. This is formalized in Kaufmann (2012) as the Epistemic Uncertainty Condition:

-

(68)

An utterance of an imperative p in context c is felicitous only if the speaker takes both p and ¬p to be possible.

Although there are different ways to incorporate this intuition into the contribution of imperative mood, following Kaufmann’s original intuition, I model this as an additional presupposition triggered by mood\(_{\textsc{Imp}}\). Given the Epistemic Uncertainty Condition, we add to the denotation in (66) that the set of worlds consistent with the Speaker’s beliefs in \(w_{c}\) (\(Bel^{\prime} _{Sc}\)) contains \(w_{1}\) and \(w_{2}\) such that p is false in \(w_{1}\) and true in \(w_{2}\).

-

(69)

Given the second presupposition in (69), we can exclude the possibility that the world variable is restricted by the world of the utterance context c, since this would amount to an assertion of p which is contradicted by the presupposition (the speaker takes both p and not p to be possible).Footnote 18 Given that the world variable cannot be valued in context c, and in the absence of a quantificational operator to bind it, existential closure applies to bind the world variable similarly to the existential closure in other cases (e.g. event variable, individual variable in passives).Footnote 19

In this case, the meaning we get for an imperative like stay is that there is a world \(w^{\prime}\) in which the addressee stays in \(w^{\prime}\). The presuppositions will ensure that the relevant worlds are restricted to those consistent with the speaker’s desires regarding the addressee’s actions and, in addition, via the uncertainty presupposition, it is ensured that the speaker considers both alternatives (A stay, ¬stay) possible.

-

(70)

The formulation in (69) allows us to detach the information regarding the force of imperatives from the meaning of imperative mood, thus providing us with the flexibility we need to account for the cases when the imperative combines with adverbials encoding specific force like kalitera ‘better’ and oposdipote ‘definitely.’ Before moving on to see how we can derive the interpretations for these cases, let me go through some questions raised by the current proposal. Some of these questions constitute long-standing puzzles in the literature of imperatives, like the issue of the flavor of imperatives (i.e. bouletic, teleological, deontic) or the way to derive performativity in imperatives, especially under a modal approach. Before addressing these more general issues, I would like to elaborate on an issue specific to the present analysis, namely the way the presupposition of imperative mood projects (Heim 1983, 1992; Schlenker 2011).

Empirically, in order to derive the desired interpretation that there is some world which satisfies the speaker’s desires, and not the impossible reading, that all possible worlds are consistent with the speaker’s desires, either we need to have local accommodation or alternatively we can assume that the presupposition enforces an implicit domain restriction to those worlds which are consistent with the speaker’s desires. In the case of existential closure either approach would work. However for the cases of oposdipote- and kalitera-imperatives, local accommodation is not straightforward.Footnote 20 Thus, I take it that in all environments the weak inference we derive is not due to local accommodation but rather due to an implicit domain restriction enforced by the presupposition. Since contextual domain restriction in quantifiers is highly frequent especially when the domain broadly refers to a large set of individuals (e.g. child below), a presupposition can join the domain restriction of the quantifier. To illustrate, in a sentence like Every child who walks his/her dog..., we do not get a presupposition that every child has a dog rather we restrict the domain of quantification into children who have dogs. Similarly in the case of imperative mood, I will assume from now on that the presupposition results in contextual domain restriction, such that we now quantify over worlds that are consistent with the speaker’s desires.Footnote 21

Now we can turn to the actual content of the presupposition. In the present paper, imperatives have a bouletic/prioritizing character such that the prejacent is at least, consistent with the speaker’s desires/priorities (for the bouletic character of imperatives see also Bierwisch 1980; Wilson and Sperber 1988; Condoravdi and Lauer 2012; Stegovec 2019). On the one hand, this captures the empirical observation that imperatives require that the speaker is not against the actualization of the event described by the prejacent (speaker endorsement in Kaufmann 2012). On the other hand, there are uses of imperatives which pose a challenge for an analysis of imperatives as expressing the speaker’s desires or priorities. For example, the case of disinterested advice (Kaufmann 2016) as in (71), in which the speaker (S) has no interest or preference for the addressee (A) to take the train:

-

(71)

A: How can I get to Nuremberg from Berlin?

S: Take the train.

Condoravdi and Lauer (2012) explain cases like (71) by general pragmatic principles. According to a general cooperative principle, the speaker adopts the addressee’s goals/preferences as long as they do not contradict his/her own (thus satisfying speaker endorsement). I follow Condoravdi and Lauer’s (2012) analysis in this respect, arguing that in cases of disinterested advice in which the addressee’s priorities contradict the priorities of the speaker, advising fails as in the case of the dialogue in (72). This example also starts out as disinterested advice but ends up in different opinions between B and A, such that B doesn’t seem willing to adopt A’s view, despite not having a particular interest or preference in the given situation.

-

(72)

A. How do I cut the expenses of my company?

B. Fire all the employees who take high salaries.

A. But you know I’d rather go bankrupt instead of doing this.

B. I know but this is my opinion. In any case, I don’t care. You can do whatever you want.

A second puzzle is how to derive performativity in imperatives. This is especially challenging for modal approaches to imperatives which are truth-conditional like the one developed here. As it has long been noticed we cannot judge an imperative as true or false. We can challenge an imperative as in (73a) but not directly target its truth or falsity with an expression like This is not true/You are lying, etc. (73b).

-

(73)

Invite Meli!

-

a.

Wait a minute! I thought you don’t want me to invite Meli.

-

b.

#This is not true. / #You are lying. You don’t want me to invite Meli.

-

a.

In order to account for the performativity effect, I follow Kaufmann (2012, 2016) who argues that performativity of modal verbs such as must and the imperative should be treated in tandem and derived from the context they appear in. In particular a performative interpretation arises when i) a priority modal provides an answer to a Question under Discussion (QUD) that expresses a decision problemFootnote 22 and ii) the speaker has epistemic authority over the issue. For example, an imperative such as Eat the apple can be understood as an answer to a decision problem in different ways, depending on the context, e.g. it could be that the addressee wants to eat something but he does not know what or he is not sure whether he is allowed to eat an apple. In this case, it is expected that the addressee will follow the advice provided for the decision problem, therefore resulting in the addressee taking action. What is crucial for the difference between typical deontic modals and imperatives is that imperatives presuppose (i) and (ii), therefore guaranteeing that they are always performative. Adapting Kaufmann (2012)’s analysis into the present analysis, we can integrate the requirement for a practical context as a presupposition, such that mood\(_{\textsc{imp}}\) is defined only if it occurs in a practical context.Footnote 23 Now that we have tackled the basic issues with the meaning of imperatives we turn to the analysis of imperatives which combine with an overt adverbial.

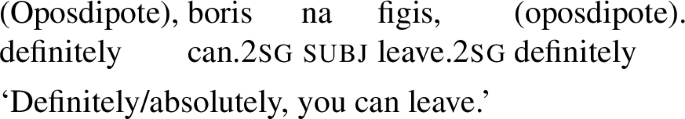

5.3 Oposdipote-imperatives

As we saw in Sect. 5.1, imperatives combining with oposdipote ‘definitely’ yield an unambiguously necessity reading. Given that oposdipote on its own is analysed as an adverbial conveying necessity, it is natural, under the present analysis, to analyse it as a quantificational operator which, upon merging with the imperative, binds the world variable and yields a universal reading.

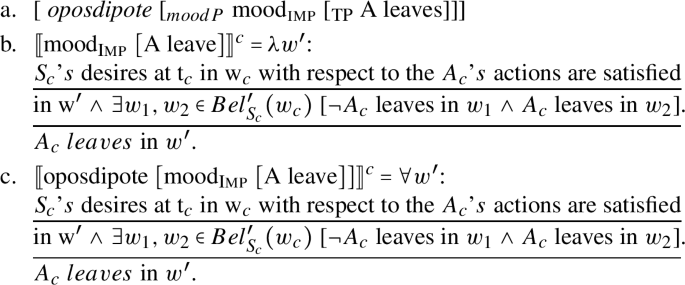

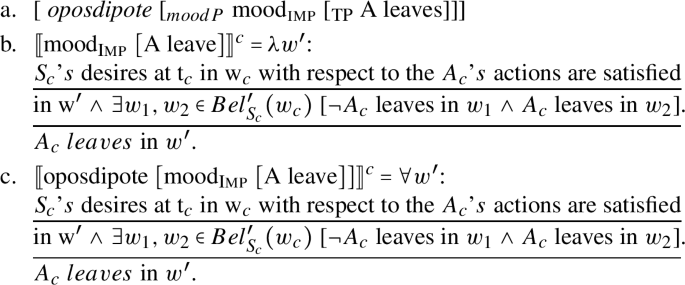

In particular, oposdipote combines with a partial function from worlds to truth values and universally quantifies over the world variable. The domain condition in (74) guarantees that the worlds of evaluation will be the worlds of evaluation in p. This means that whatever restriction is introduced in the embedded proposition is projected in the entire proposition. Thus, when oposdipote combines with an imperative, mood\(_{\textsc{imp}}\)P as in (75), it universally quantifies over the world variable, and it ends up with the same domain restriction that imperative mood enforces by presupposing that the worlds of evaluation are consistent with the speaker’s desires and the Epistemic Uncertainty Condition. The meaning we derive by combining oposdipote with the imperative proposition as in (76b) is that in all worlds in which the speaker’s desires with respect to the addressee’s actions are satisfied, the prejacent is true as shown in (76c).

-

(74)

\([\!\![\text{oposdipote}]\!\!]^{c} = \lambda p_{\langle st\rangle}\). \(\forall{w^{\prime}}\): \(w^{\prime}\) ∈ dom(p). \(p(w^{\prime})=1\)

-

(75)

-

(76)

Under this analysis, oposdipote is treated as a quantificational adverbial quantifying over worlds. The domain restriction ensures that the worlds are restricted to those consistent with the speaker’s desires as required by the semantic contribution of imperative mood.

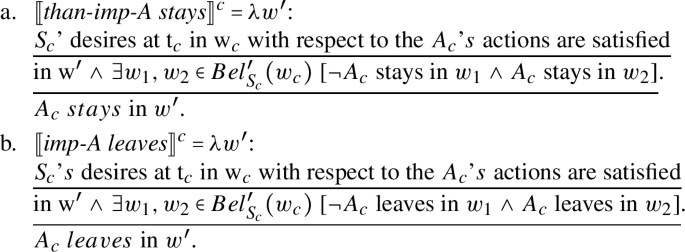

5.4 Kalitera-imperatives

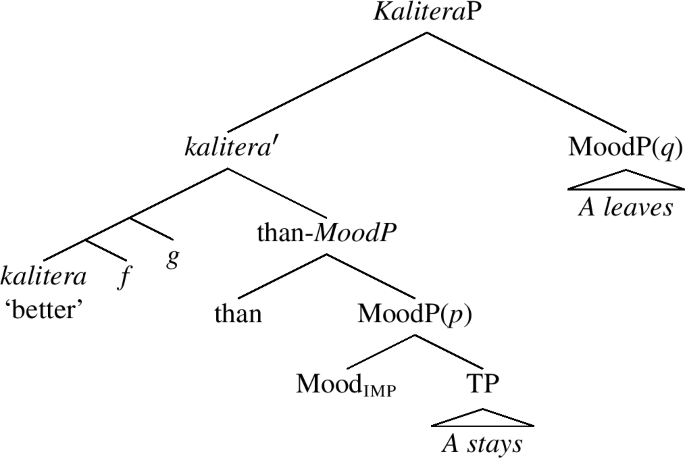

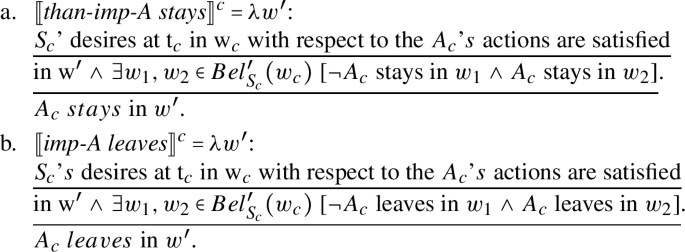

The adverbial kalitera ‘better’ involves a comparison between two alternatives, suggesting that one is better than the other. Formalizing this intuition, kalitera can be analysed as a comparative operator which takes two propositions, p and q, as its arguments and establishes a comparative relation between the two.Footnote 24 Notably, kalitera ‘better’ seems to have a modal flavor on its own, since it always gives rise to prioritizing modal interpretations. Therefore, I propose that a doxastic modal base f and a bouletic ordering source g is part of its meaning (cf. von Fintel 1999 for want). Otherwise, it would be expected that kalitera ‘better’ could be consistent with an epistemic interpretation (like oposdipote) which is never the case.

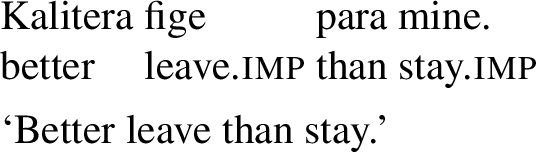

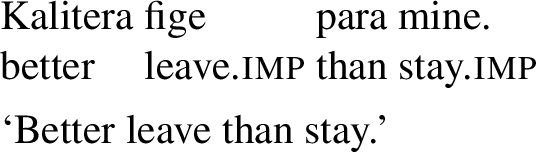

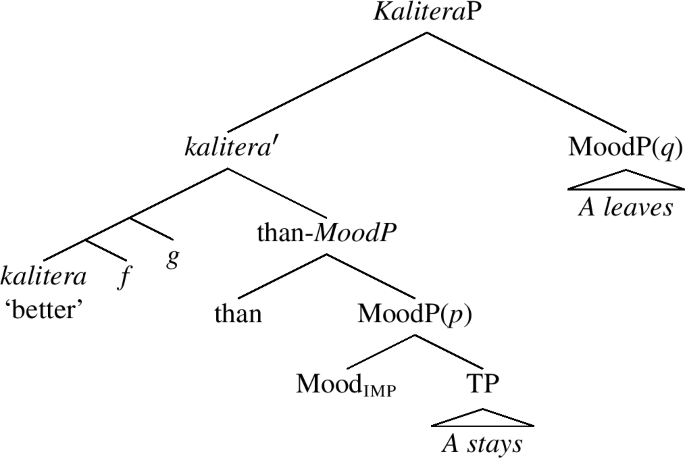

Syntactically, kalitera-imperatives involve two clauses. The than-clause is the internal argument of kalitera and it can be realized overtly as shown in (77), repeated from (59), or covertly.Footnote 25 As shown in (78) kalitera combines with two mood\(_{\textsc{imp}}\)Ps, which is evident from the fact that a morphological imperative can appear in the than-clause.

-

(77)

-

(78)

kalitera-imperatives