Abstract

Current phasal models of words differ from one another in two main ways: which heads are phasal and whether a phase head allows higher heads to access its complement. Through an investigation of verbs in Muskogee, this paper argues that in some languages, words have functional phase heads that divide them into two domains and that block all higher heads from access to morphemes. Specifically, Muskogee verbs contain aspectual phase heads (Asp0), which separate the verb into a sub-aspectual, VP-level domain—Phase One (Φ1)—and a superaspectual, InflP-level domain—Phase Two (Φ2). As previous work on Muskogee has shown, Φ1 (the ‘Stem’ in previous literature) and Φ2 form separate domains both in phonology, affecting stress and tone patterns, and in temporal semantics. This paper makes the novel observation that morphemes in Φ1 and Φ2 do not interact with each other in rules of allomorphy or allosemy, despite widespread interaction within each domain. An Asp0 phase head that follows the strong PIC1 accounts for the lack of interaction between Φ1 and Φ2. Categorizers, which are typically taken to be phase heads, behave differently from Asp0 in Muskogee, though their phasal status is unclear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Muskogee, also known as ‘Maskoke,’ ‘Creek,’ and ‘Seminole,’ is a member of the Muskogean language family spoken in the southern United States, originally in the current states of Alabama and Georgia. Muskogee is spoken in three different communities: by around 3,000 people in the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma, about 700 in the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, and about 200 in the Seminole Tribe of Florida (Martin 2011:17; numbers estimated from 2000, so may be different now). In the latter two communities, the dialects are known as “Oklahoma Seminole Creek” and “Florida Seminole Creek,” respectively.

Most of the data in this paper come from the Creek (Muskogee) Grammar, by Jack Martin with speakers Margaret McKane Mauldin and Juanita McGirt (cited as Martin 2011). Other data come from Hardy’s (1988) dissertation, Muskogee narratives in Gouge (2004), (Kimberly) Johnson’s (2018, 2019) work on Muskogee syntax and semantics, and personal communication with both Martin and Johnson. This paper is informed by Haas’ (1940, 1977) descriptive work on Muskogee morphology, temporal semantics and prosody, Nathan’s (1977) grammar of Florida Seminole Creek, Hardy’s (1988) investigation of verbal morphosyntax and semantics in Muskogee, Martin’s (1991) study of argument structure and transitivity, Martin and (Keith) Johnson’s (2002) acoustic study of prosody, and Martin’s (2010) and Johnson’s (2019) investigations of tense. This work is a revision and extension of the analysis of Muskogee in Guekguezian (2017:Sect. 3). Any sources of empirical disagreement are noted.

Muskogee also has periphrastic constructions using a main verb and an auxiliary verb, the most common of which is ‘be’ (/ooM/ in Hardy 1988, /om/ in Martin 2011: Sect. 32). The auxiliary ‘be’ /ooM, o:m/ has the effect of backgrounding the main verb (Hardy 1988:336) or asserting information (Martin 2011:300–301); it also has evidential uses (Johnson 2019). Other auxiliaries “express[] modality, evidentiality, or aspect” (Martin 2011:298).

The position of auxiliaries in the clausal structure requires more research. On the one hand, both the main verb and auxiliary verb have autosegmental morphology encoding aspect, which can be the same or different between the two verbs (Martin 2011:300). This suggests that auxiliary constructions are biclausal, with separate VP projections, as suggested by one reviewer. On the other hand, some Φ2 suffixes appear on the main verb and others on the auxiliary verb (Martin 2011:301–302). This suggests that the main verb and the auxiliary are in the same clause, with the auxiliary moving up into IP, as another reviewer suggests. The morphosyntax of auxiliaries is outside of the scope of this paper.

Thanks to Daniel Harbour for suggesting the term “allotypy”.

This Agr head is likely distinct from the patient agreement prefixes in Φ1 that agree with speech participant for person and number: /ca-/ 1st.sg, /po-/ 1st.pl, and /ci-/ 2nd (Martin 2011:168–170). These patient agreement prefixes may spell out either a separate Agr head or an pronominal argument in a specifier slot.

Tables 10–12 do not give full Muskogee verbs, but only the exponents of the root, transitivity, and number agreement (all taken from Martin 2011:Sects. 23–24); a complete verb requires aspect morphology (including /Ø/ irr) and an overt mood suffix (in matrix clauses) or switch-reference clitic (in embedded clauses).

If, on the other hand, the examples in (38) are cases of allotypic interaction, Asp0 can still be a phase head if /-ip/ spontaneous is included in the Asp projection. /-ip/ provides aspectual semantics and sits at the right edge of the Φ1 domain (Martin 2011, though cf. Hardy 1988). If /-ip/ is adjoined to Asp, in its specifier, or the exponent of a feature on Asp, /-ip/ would be phase-accessible to both Φ1 and Φ2 morphemes, similarly to Asp0 itself. While /-ip/ is clearly in the first phonological domain as defined by footing and tone (Sect. 3.1), this does not necessarily mean that /-ip/ cannot be in the Asp projection. For example, in Bošković’s (2016) proposal, PF domains contain the phase heads themselves, so that material in the Asp projection would sit in the first phonological domain (though see Sect. 5.2 for evidence that Asp morphology’s position in the first phonological domain is compatible with being spelled out at the second phase). The same account may work for /-aha:n/ prospective, which is similar to /-ip/ in position and aspectual semantics.

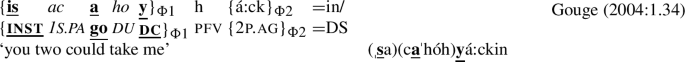

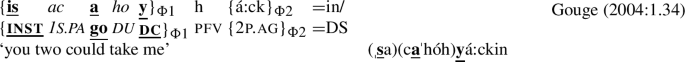

Similar conditions may obtain on the LF side if Martin is correct that /Ø/ (‘Zero-grade’) is a default form used when other, semantically contentful aspects are not appropriate (I have instead adopted Hardy’s (1988) proposal that /Ø/ Asp0 encodes irrealis). Under Martin’s analysis, /Ø/ Asp0 should not prevent linear adjacency for semantics, so Φ1–Φ2 allosemic interaction should be likely across /Ø/ Asp0. Allosemic interaction does occur between morphemes that are separated by agreement morphology. For example, in (i), the root ‘go’ has the alloseme ‘take’ in the context of /is-/ instrumental and /-y/ direct causative. In (i), the agreement markers /ac-/ and /-ho/ interrupt linear adjacency between the root /a/ ‘go’ and both /is-/ and /-y/, respectively.

-

(i)

Allosemy also occurs across agent agreement in Φ2: the Φ2 head durative has an ability meaning in the context of eventive aspect, no matter whether agreement intervenes (Martin 2011:249–251, 305). As an anonymous reviewer points out, agreement morphology does not affect the truth conditions and may be ignored at LF for purposes of linear adjacency (Marantz 2013; see Rice 2000 for Athabaskan).

-

(i)

An initially plausible argument against categorizers being phasal in Muskogee is that Φ1 morphemes above v interact with the root. As demonstrated in Sect. 3.1, Muskogee verbs exhibit considerable allomorphic interaction among the root and both transitivity and number agreement suffixes, which depend on the other two morphemes for VI insertion ((17)–(24), Tables 10–12). Under the assumption that only one of the two suffixes is v, the other suffix must be above v and should not be able to access the root if v were a phase head following PIC1. Moreover, other Φ1 morphemes trigger allosemy selection with the root, including the reciprocal, instrumental, and several locative prefixes ((26) above). These morphemes are higher than the categorizer v, so v does not block access to the root.

However, as multiple reviewers point out, there are several problems with this line of argumentation. First, if the root head-adjoins to its categorizer (following, e.g., Marantz 2013; Kastner 2016), it would not be the complement of v, and thus not be rendered inaccessible to other Φ1 morphemes by PIC1. Second, v may be null and the two overt suffixes higher: number agreement in AgrPat and transitivity in Voice. Since v is null, it would not block interaction between the root, Agr and Voice (see, e.g., Embick 2010, 2013, Marantz 2013 for interaction across null categorizers). Alternatively, number agreement may be a selectional feature on either the root or v, so that it is adjacent to both. Node-sprouting (Choi and Harley 2019) would then occur in the postsyntax so that the suffix can be inserted.

With verbal nouns in /-ka/, the direct causative suffix /y/ is dropped. For example, in (49c), the typical allomorph of v/VoiceDC used with the root /itipo/ ‘fight’, /y/, is not present (though Martin 2011 does not say so, it seems possible that the Φ1 /itipo-y/ contains /iti-/ reflexive). While Martin takes /y/ to be an allomorph of v/VoiceDC, Hardy gives it as a “morphophoneme variant conditioned by a following vowel” when the root (+ Agr) ends in a vowel. Almost all following suffixes begin in a vowel, so that /y/ is almost always present in such cases. Other allomorphs of v/VoiceDC, like /ic/ in (49a), are present with /-ka/, which thus cannot attach, below v/Voice. On Martin’s analysis, /y/ is deleted (or /Ø/ is inserted) in the context of /-ka/, while on Hardy’s analysis /y/ is inserted in the context of other morphemes (or in the context of following vowels). Alternatively, /y/’s appearance is governed by context-dependent readjustment rules. Since on a categorizing phase analysis, both v and n are phase heads, the allomorphic interaction between /-ka/ gerundive and /-y/ v/VoiceDC is allowed by the Activity Corollary (Embick 2013:6).

There are two possible counterarguments to there being an Asp0 phase head in agentive nominalizations. First, Martin gives glosses of agentive nominalizations with specialized meanings, like [famí:c-a] ‘muskmelon, cantaloupe’ from /famic/ ‘scented’ (2011:108). These are likely not cases of allosemy, but instead conventionalized specializations of the agentive’s basic meaning of “one who does/is X all the time.” E.g., [fami:c-a] may mean “one that smells all the time,” but be restricted in actual usage to the stinky fruit. See Marantz (2013:105–106) for the distinction between allosemy, which must be phase-local, and special or idiomatic meanings, which do not have to be.

Second, Martin states that agentive nominalizations have a single phonological domain: “agent nominalizations are accented like nouns. ‘Long’ verbs in the lengthened grade generally have two accents (opóna:y-ís ‘he/she is speaking’), but agent nominalizations do not (oponá:y-a ‘speaker’)” (2011:108). However, independent phonological considerations may rule out two accents in agentive nominalizations, such as clash avoidance *[(o.pó).(ná:).ya)] or the final light syllable, which cannot be footed by itself *[(o.pó).(na:).(yá)]. Because agentives always consist of a Φ1 domain with a final heavy syllable and are followed by the single, light vowel [-a], it is unclear whether these forms have one or two phonological domains. This applies to all agentive nominalizations as far as I am aware, not only agentives where the Φ1 domain has the same shape as /oponay/.

References

Abels, Klaus. 2003. Successive cyclicity, anti-locality, and adposition stranding. PhD diss., University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Arad, Maya. 2003. Locality constraints in the interpretation of roots: The case of Hebrew denominal verbs. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 21: 737–778.

Baker, Mark. 1986. The mirror principle and morphosyntactic explanation. Linguistic Inquiry 16(3): 373–415.

Bobaljik, Jonathan. 2000. The ins and outs of contextual allomorphy. University of Maryland Working Papers in Linguistics 10: 35–71.

Bobaljik, Jonathan, and Susi Wurmbrand. 2013. Suspension by domain. In Distributed morphology today: Morphemes for Morris Halle, eds. Alec Marantz and Ora Matushansky, 185–198. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Borer, Hagit. 2005. Structuring sense. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bošković, Željko. 2014. Now I’m a phase, now I’m not a phase: On the variability of phases with extraction and ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 45: 27–89.

Bošković, Željko. 2016. Contextual phasehood and the ban on extraction from complements of lexical heads: When does X become a phase?. In Phase theory and its consequences, eds. M. Yasui and M. Mizuguchi, 5–39. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

Caha, Pavel. 2009. The nanosyntax of case. PhD diss., University of Tromsø.

Cheng, Lisa, and Laura Downing. 2012. Prosodic domains do not match spell-out domains. McGill Working Papers in Linguistics 22(1).

Cheng, Lisa, and Laura Downing. 2016. Phasal syntax = cyclic phonology? Syntax 19(2): 156–191.

Choi, Jaehoon, and Heidi Harley. 2019. Locality domains and morphological rules. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 37(4): 1319–1365.

Chomsky, Noam. 1993. A minimalist program for linguistic theory. In The view from building 20: Essays in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, eds. Ken Hale and Samuel Keyser, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Minimalist essays in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–115. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2004. Beyond explanatory adequacy. In Structures and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structures, ed. Adriana Belletti. Vol. 3, 104–131. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistics theory, eds. Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta, 133–166. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Davidson, Donald. 1980. Essays on actions and events. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Demirdache, Hamida, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria. 2000. The primitives of temporal relations. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 157–186. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Demirdache, Hamida, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria. 2003. The syntax of time adverbs. In The syntax of time, eds. Jacqueline Gueron and Jacqueline Lecarme, 143–179. Cambridge: MIT Press.

den Dikken, Marcel. 2007. Phase extension: Contours of a theory of the role of head movement in phrasal extraction. Theoretical Linguistics 33: 1–41.

Embick, David. 2010. Localism versus globalism in morphology and phonology. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Embick, David. 2013. Locality across domains: From morphemes to structures to sounds. North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 44: 18–20.

Ernst, Thomas. 2002. The syntax of adjuncts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ershova, Ksenia. 2019. Two paths to polysynthesis: Evidence from West Circassian nominalizations. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 38: 425–475.

Gallego, Ángel. 2010. Phase theory. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Gouge, Earnest. 2004. Totkv mocvse/new fire: Creek folktales. Edited and translated by Jack B. Martin, Margaret McKane Mauldin, and Juanita McGirt. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Guekguezian, Peter. 2017. Prosodic recursion and syntactic cyclicity inside the word, PhD diss., University of Southern California.

Haas, Mary. 1940. Ablaut and its function in Muskogee. Language 16: 141–150.

Haas, Mary. 1977. Tonal accent in Creek. In Studies in stress and accent, Southern California occasional papers in linguistics 4, ed. Larry Hyman, 195–208. Los Angeles: University of Southern California.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20: Essays in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, eds. Ken Hale and Samuel Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Halle, Morris, and Jean-Roger Vergnaud. 1978. Metrical structures in phonology, Ms., MIT.

Halle, Morris, and Jean-Roger Vergnaud. 1987. An essay on stress. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hardy, Donald E. 1988. The semantics of Creek morphosyntax, PhD diss., Rice University.

Harley, Heidi. 2013. External arguments and the mirror principle: On the distinctness of voice and v. Lingua 125: 34–57.

Harley, Heidi, and Mercedes Tubino-Blanco. 2013. Cycles, vocabulary items, and stem forms in Hiaki. In Distributed morphology today: Morphemes for Morris Halle, eds. Alec Marantz and Ora Matushansky, 117–134. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harwood, Will. 2013. Being progressive is just a phase: Dividing the functional hierarchy. PhD diss., University of Gent.

Hayes, Bruce. 1995. Metrical stress theory: Principles and case studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hinterhölzl, Roland. 2006. The phase condition and cyclic spell-out: Evidence from VP-topicalization. In Phases of interpretation, ed. Mara Frascarelli, 237–259. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Iatridou, Sabine, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Roumyana Izvorski. 2001. Observations about the form and meaning of the perfect. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 189–238. Cambridge: MIT Press. Reprinted in Perfect explorations, ed. Artemis Alexiadou, Monika Rathert and Arnim von Stechow. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Johnson, Kimberly. 2018. Optional case in Muskogee Creek: Phase sensitive morphology. Ms., UMass Amherst.

Johnson, Kimberly. 2019. Graded and evidential tenses in Mvskoke (Creek). Ms., UMass Amherst.

Kastner, Itamar. 2016. Form and meaning in the Hebrew verb. PhD diss., NYU.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1996. Severing the external argument from its verb. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, eds. Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 109–138. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Marantz, Alec. 2001. Words and things. Handout: MIT.

Marantz, Alec. 2007. Phases and words. In Phases in the theory of grammar, ed. S-H. Choe, 196–226. Seoul: Dong-in.

Marantz, Alec. 2013. Locality domains for contextual allomorphy across the interfaces. In Distributed morphology today: Morphemes for Morris Halle, eds. Alec Marantz and Ora Matushansky, 95–115. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Martin, Jack. 1991. Lexical and syntactic aspects of Creek causatives. International Journal of American Linguistics 57(2): 194–229.

Martin, Jack. 2010. How to tell a Creek story in five past tenses. International Journal of American Linguistics 76(1): 43–70.

Martin, Jack. 2011. A grammar of Creek (Muskogee). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Martin, Jack, and Keith Johnson. 2002. An acoustic study of “tonal accent” in Greek. International Journal of American Linguistics 68(1): 28–50.

Marvin, Tatjana. 2002. Topics in the stress and syntax of words. PhD diss., MIT.

McCloskey, James. 1997. Subjecthood and subject positions. In Elements of grammar, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 197–235. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Merchant, Jason. 2015. How much context is enough? Two cases of span-conditioned stem allomorphy. Linguistic Inquiry 46(2): 273–303.

Nathan, Michele. 1977. Grammatical description of the Florida Seminole dialect of Creek. PhD diss., Tulane University.

Newell, Heather. 2008. Aspects of the morphology and phonology of phases. PhD diss., McGill University.

Newell, Heather. 2014. Phonological persistence. Paper presented at the 8th North American phonology conference. Montreal: Concordia University.

Nissenbaum, Jon. 2000. Investigations of covert phrase movement. PhD diss., MIT.

Noyer, Rolf. 1997. Features, positions and affixes in autonomous morphological structure. New York: Garland.

Pancheva, Roumyana. 2003. The aspectual makeup of perfect participles and the interpretations of the perfect. In Perfect explorations, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Monkia Rathert, and Arnim von Stechow, 277–306. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1989. Verb movement, universal grammar, and the structure of IP. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 365–424.

Prince, Alan. 1983. Relating to the grid. Linguistic Inquiry 14(1): 19–100.

Pylkkänen, Liina. 2008. Introducing arguments. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ramchand, Gillian. 2008. Verb meaning and the lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rice, Keren. 2000. Morpheme order and semantic scope. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ritter, Elizabeth, and Martina Wiltschko. 2014. The composition of INFL. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32(4): 1331–1386.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar, 281–337. Dordrecht: Springer.

Samuels, Bridget. 2010. Phonological derivation by phase: Evidence from Basque. In University of Pennsylvania working papers in linguistics: Proceedings of the 33rd Penn linguistics colloquium, ed. Jon Scott Stevens, 166–175. University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia

Smith, Carlota. 1991. The parameter of aspect. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Starke, Michal. 2010. Nanosyntax: A short primer to a new approach to language. Nordlyd 36(1): 1–6.

Stowell, Tim. 1993. The syntax of tense. Ms., UCLA.

Šurkalović, Dragana. 2015. The no-reference hypothesis: A modular approach to the syntax-phonology interface. PhD diss., University of Tromsø/CASTL.

Svenonius, Peter. 2004. On the edge. In Peripheries, eds. David Adger, Cecile de Cat, and George Tsoulas, 259–287. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Svenonius, Peter. 2012. Spanning. Ms., University of Tromsø, CASTL.

Taraldsen, Knut Tarald. 2010. The nanosyntax of Nguni noun class prefixes and concords. Lingua 120: 1522–1548.

Travis, Lisa. 2010. Inner aspect: The articulation of VP. Dordrecht: Springer.

Wurmbrand, Susi. 2014. Tense and aspect in English infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry 45: 403–447.

Zagona, Karen. 1990. Times as temporal argument structure. Talk given at the Time in language conference, MIT.

Zanuttini, Raffaella. 1997. Negation and clausal structure: A comparative study of Romance languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the following people who have supported and improved the work in this paper. Jack Martin has graciously provided detailed answers to my numerous questions about the phonology and morphology of Muskogee verbs over the past few years. Moreover, without Jack’s decades of fieldwork on Muskogee and subsequent grammar, this paper would not have been possible. I also thank Kimberly Johnson both for discussion of her own fieldwork on Muskogee and for her insights into Muskogee morphosyntax and semantics. I am indebted to the other linguists who have worked on Muskogee over the last several decades, especially Mary Haas and Donald Hardy, and of course their Muskogee language consultants, without whom neither their work nor mine would be possible.

My postdoctoral adviser at University of Rochester, Joyce McDonough, has provided extensive and constructive feedback on my examination of morphological constituency in Muskogee. Joyce has consistently kept me focused on finding empirical generalizations in the data. The entire Department of Linguistics and Center for Language Sciences at the University of Rochester has supported and influenced my work on Muskogee over the last two years. Solveiga Armoškaitė and Katy McKinney-Bock have both pored over drafts of this work at different stages; their cogent critiques have vastly improved both my account and my exposition. Hossep Dolatian has also offered helpful ideas that have benefited this paper. I further appreciate the feedback on earlier stages of this work by my dissertation committee at the University of Southern California: my adviser, Karen Jesney, and my other committee members, Rachel Walker, Roumyana Pancheva, Maria Luisa Zubizarreta, and Mario Saltarelli. I acknowledge the valuable input on previous versions of this work from the audience at MoMOT 2018. Lastly, I thank the constructive feedback given by three anonymous reviewers and the associate editor, Daniel Harbour, on previous versions of this paper. Any and all errors in the work are solely my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guekguezian, P.A. Aspectual phase heads in Muskogee verbs. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 39, 1129–1172 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09495-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09495-7