Abstract

Since Kuno (1973), it has been widely acknowledged that the choice of Japanese demonstratives (the distal a-series, the medial so-series, and the proximal ko-series) in their anaphoric use is regulated by rules concerned with the speaker’s and the hearer’s knowledge of, or acquaintance with, the referent. In cross-linguistic discussions of anaphoric demonstratives, on the other hand, the effect of the interlocutors’ knowledge of the referent has hardly been acknowledged. This paper has the following goals. First, it critically reviews Kuno’s seminal analysis of Japanese anaphoric demonstratives, and presents a modified version of it. Second, it argues that the interlocutors’ knowledge of the referent is relevant to the choice of the English demonstratives this and that too. Third, it provides a formal semantic analysis of anaphoric demonstratives in the two languages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For the sake of simplicity, we will say “adnominal demonstrative X refers to Y” to mean “an NP with X refers to Y.”

Throughout the article, examples without specification of the source are constructed by the authors.

The question of what exactly counts as “know personally” will be taken up below.

The abbreviations in glosses are: Acc = accusative, Acc = accusative, Adv = adverb, Attr = attributive, Ben = benefactive auxiliary, Caus = causative, Cl = classifier, Cond = conditional, Cop = copula, Dat = dative, DAux = discourse auxiliary, DP = discourse particle, Evid = evidential particle, EvidAux = evidential auxiliary, Ger = gerund, Imp = imperative, Inf = infinitive, Loc = locative, Neg(Aux) = negation (auxiliary), Nmz = nominalizer, Nom = nominative, Npfv = nonperfective auxiliary, NSHon = non-subject honorific, Opt = optative, Pass = passive, Pfv = perfective auxiliary, Plt(Aux) = polite(ness auxiliary), Pot = potential, Pro = pronoun, PP = past participle, Prs = present, Pst = past, SHon = subject honorific, Top = topic, Vol = volitional. Subscript ko, so, and a in the glosses/translations indicate that the corresponding Japanese expression is a ko-, so-, and a-demonstrative, respectively.

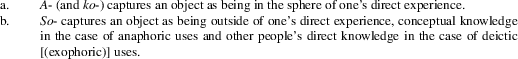

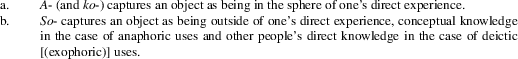

Kuroda (1979) puts forth the following characterizations of Japanese demonstratives (the translation and summary by Takubo and Kinsui 1997:753).

-

(i)

Kinsui and Takubo (1990) claim that a so-demonstrative, whether used exophorically or anaphorically, refers to an entity belonging to the hearer’s domain. Takubo and Kinsui (1997) propose that a speaker uses an anaphoric so-demonstrative to identify an object in the “indirect experience domain (I-domain)” in his mental database, which is linked to the temporary memory set up for the purpose of each discourse, and an anaphoric a-demonstrative to identify an object in the “direct experience domain (D-domain),” which is linked to the long-term memory. As we understand them, these accounts all fail to explain why the use of a so-demonstrative is felicitous in cases like (5A) and (6).

-

(i)

It is interesting to ask how various means of distant communication, such as letters/written notes, emails, phone calls, and video chats, factor into the establishment of the acquaintance relation. We leave this issue for future research.

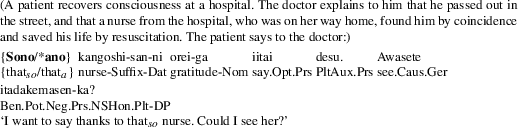

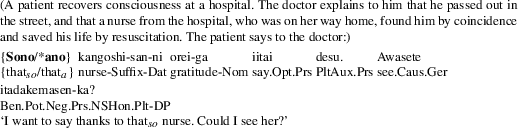

In a case where one has the knowledge that he has had contact with some referent x but did not directly perceive it, or does not remember directly perceiving it (e.g., the nurse in (i)), x is treated as “not recognized.”

-

(i)

-

(i)

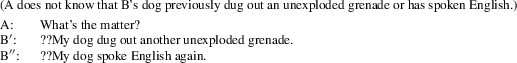

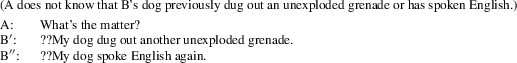

Pragmatic accommodation is relatively easy when the information to be accommodated is relatively typical or mundane, and more difficult when the information is surprising:

-

(i)

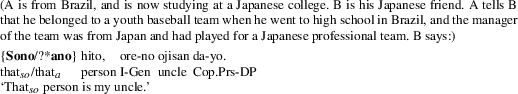

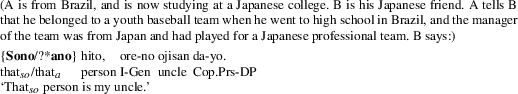

A similar effect can be observed with a Japanese anaphoric demonstrative.

-

(ii)

-

(i)

Kinsui and Takubo (1990:94–96) remark that exceptional usage of a-demonstratives is observed “in a certain kind of context where the speaker gives instructions to the hearer.”

Roberts (2002:122–124) suggests that anaphoric demonstratives are a kind of discourse-deictic demonstratives, and reference with them involves “demonstration in discourse”; we depart from her in not adopting this view.

It is interesting to ask whether the relation of “recognize” (“acquainted with”) is to be taken as a primitive, as it is here, or should be formulated with a more general apparatus for belief ascriptions. An attempt at such decomposition, which utilizes a DRT-style formulation of attitudes with anchoring functions, was made in Oshima and McCready (2014).

https://guidedbycereal.com/europe/london/ (Accessed 2 June 2014).

“ ‘Get off your asses for these old broads!’: Elizabeth Taylor, aging and the television comeback movie,” an article on Celebrity Studies 3(1) (published in 2012; doi:10.1080/19392397.2012.644717).

References

Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2004. Evidentiality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, Stephen R., and Edward L. Keenan. 1985. Deixis. In Language typology and syntactic description, Vol. 3: Grammatical categories and the lexicon, ed. Timothy Shoppen, 259–308. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Büring, Daniel. 2011. Pronouns. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. Klaus von Heusinger, Caludia Maienborn, and Paul Portner, Vol. 2, 971–996. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Corbett, Greville. 1991. Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Diessel, Holger. 1999. Demonstratives: Form, function and grammaticalization. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Evans, Gareth. 1977. Pronouns, quantifiers, and relative clauses. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 7: 467–536.

Gundel, Jeanette, Nancy Hedberg, and Ron Zacharski. 1993. Cognitive status and the form of referring expressions in discourse. Language 69: 274–307.

Heim, Irene. 1982. The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Heim, Irene. 1992. Presupposition projection and the semantics of attitude verbs. Journal of Semantics 9: 183–221.

Himmelmann, Nikolaus A. 1996. Demonstratives in narrative discourse: A taxonomy of universal uses. In Studies in anaphora, ed. Barbara A. Fox, 205–254. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Hirose, Yukio. 1995. Direct and indirect speech as quotations of public and private expression. Lingua 95: 223–238.

Hoji, Hajime, Satoshi Kinsui, Yukinori Takubo, and Ayumi Ueyama. 2003. The demonstratives in modern Japanese. In Functional structure(s), form and interpretation: Perspectives from East Asian languages, eds. Yen-hui Audrey Li and Andrew Simpson, 97–128. New York: Routledge.

Iori, Isao. 1996. Shiji to daiyoo: Bunmyaku shiji ni okeru shiji hyoogen no kinoo no chigai. Gendai Nihongo Kenkyuu 3: 73–91.

Kaplan, David. 1989. Demonstratives. In Themes from Kaplan, eds. Joseph Almog, John Perry, and Howard Wettstein, 481–563. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kennedy, Christopher. 2007. Vagueness and grammar: The semantics of relative and absolute gradable adjectives. Linguistics and Philosophy 30: 1–45.

Kinsui, Satoshi, and Yukinori Takubo. 1990. Danwa kanri riron kara mita nihongo no shijishi. In Ninchi kagaku no hatten, ed. Japanese Cognitive Science Society, Vol. 3, 85–116. Tokyo: Kodansha.

Kuno, Susumu. 1973. The structure of the Japanese language. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kuroda, Shigeyuki. 1979. (Ko)/so/a ni tsuite. In Eigo to nihongo to: Hayashi Eiichi kyooju kanreki kinen ronbunshuu, 41–59. Tokyo: Kurosio Publishers.

Lakoff, Robin. 1974. Remarks on ‘this’ and ‘that’. In 10th annual meeting of Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS), 345–356.

Littell, Patrick, Lisa Matthewson, and Tyler Peterson. 2010. On the semantics of conjectural questions: Evidence from evidentials. In University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 28, 89–104. British Columbia: de Gruyter.

Miyazaki, Kazuhito, Taro Adachi, Harumi Noda, and Shino Takanashi. 2002. Modaritii. Tokyo: Kurosio Publishers.

Noguchi, Tohru. 1997. Two types of pronouns and variable binding. Language 73: 770–797.

Oshima, David Y. 2016. The meanings of perspectival verbs and their implications on the taxonomy of projective content/conventional implicature. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 26, 43–60. Ithaca: CLC.

Oshima, David Y., and Elin McCready. 2014. How mutual knowledge constrains the choice of anaphoric demonstratives in Japanese and English. In 28th Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation (PACLIC), 214–223.

Potts, Christopher, and Florian Schwarz. 2009. Affective ‘this’. Linguistic Issues in Language Technology 5: 1–29.

Roberts, Craige. 2002. Demonstratives as definites. In Information sharing: Reference and presupposition in language generation and interpretation, eds. Kees van Deemter and Roger Kibble, 89–196. Stanford: CSLI.

Schlenker, Phillippe. 2012. Maximize presupposition and Gricean reasoning. Natural Language Semantics 20: 391–429.

Stirling, Leslie, and Rodney Huddleston. 2002. Deixis and anaphora. In The Cambridge grammar of the English language, eds. Rodney Huddleston and Geoffrey K. Pullum, 1449–1564. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Takubo, Yukinori, and Satoshi Kinsui. 1996. Fukusuu no shinteki ryooiki ni yoru danwa kanri. Ninchi Kagaku 3: 59–74.

Takubo, Yukinori, and Satoshi Kinsui. 1997. Discourse management in terms of mental domains. Journal of Pragmatics 28: 741–758.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for valuable comments to the four anonymous reviewers and the editor Julie Anne Legate. Some materials in this article were presented at PACLIC 28 and published in Oshima and McCready (2014); thanks also to the audience there for helpful feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oshima, D.Y., McCready, E. Anaphoric demonstratives and mutual knowledge. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 35, 801–837 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-016-9356-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-016-9356-6