Abstract

Respiratory infections caused by fungal pathogens present a growing global health concern and are a major cause of death in immunocompromised patients. Worryingly, coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) resulting in acute respiratory distress syndrome has been shown to predispose some patients to airborne fungal co-infections. These include secondary pulmonary aspergillosis and mucormycosis. Aspergillosis is most commonly caused by the fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus and primarily treated using the triazole drug group, however in recent years, this fungus has been rapidly gaining resistance against these antifungals. This is of serious clinical concern as multi-azole resistant forms of aspergillosis have a higher risk of mortality when compared against azole-susceptible infections. With the increasing numbers of COVID-19 and other classes of immunocompromised patients, early diagnosis of fungal infections is critical to ensuring patient survival. However, time-limited diagnosis is difficult to achieve with current culture-based methods. Advances within fungal genomics have enabled molecular diagnostic methods to become a fast, reproducible, and cost-effective alternative for diagnosis of respiratory fungal pathogens and detection of antifungal resistance. Here, we describe what techniques are currently available within molecular diagnostics, how they work and when they have been used.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The global burden of human associated mycoses is increasing. Each year, fungi account for billions of human infections and claim over 1.5 million lives worldwide [1, 2]. Of all reported fungal deaths, 90% are attributed to the genera Cryptococcus, Candida, Histoplasma, Pneumocystis, and Aspergillus [3]. Yet, up to 80% of patients could be prevented from dying, if fungal diagnostics were universally available and antifungal agents remain effective [1].

Advances in medical treatments and the increased use of immunosuppressive drugs has dramatically increased life expectancy. Consequently, the number of immunocompromised and immunosuppressed individuals, who are overwhelmingly susceptible to opportunistic fungal infections, has also increased. Individuals at risk from opportunistic fungal infections include those undergoing solid organ transplantation, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and those with HIV/AIDS [4]. Moreover, patients diagnosed with chronic pulmonary disorders such as cystic fibrosis (CF) may undergo frequent hospitalisations due to cycles of lung inflammations from microbial colonizations and are at particular risk from opportunistic fungal infections. While bacterial colonizations are considered a primary concern, reports of yeasts and moulds in patient respiratory samples are increasing [5,6,7].

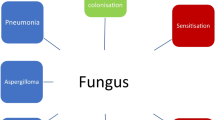

Although fungal pathogens can invade via any organ system, the primary route of infection into the body is via the respiratory tract [2]. Typically, in healthy individuals, conidia are quickly removed by mucocillary action, and those that are missed encounter neutrophils and alveolar macrophages [8], preventing attachment to the lung and subsequent infection. Continual exposure to microscopic fungi through daily inhalation of spores has the potential to cause a multitude of respiratory symptoms, which depending on the host’s immune response, can range from mild allergenic symptoms to life-threatening fungal invasions [2]. Such fungal invasions incur considerable economic burden on the health care system which is likely underestimated due to insensitive diagnostic techniques and lack of mycological surveillance [2].

The early diagnosis and implementation of effective antifungal therapy can benefit clinical outcomes [9,10,11,12]. However, the few classes of antifungals currently available are declining in efficacy due the emergence of drug-resistant fungal pathogens (Table 1). Continual exposure to antifungal compounds exerts selective pressures that can facilitate the evolution of resistance [13,14,15,16]. Additionally, fungi are equipped with intrinsic defence mechanisms, allowing them to overcome cellular stress and quickly adapt to tolerate hostile environments [17, 18]. Through adjusting cellular physiology and gaining beneficial mutations, fungi can thrive within the human lung, destroying crucial tissue, and invading vital organs. Research on the ecology, biochemistry, pathogenicity, and virulence of fungal infections is essential for the development of more efficient antifungal drugs. Yet fundamental challenges hamper the discovery of novel antifungal compounds that owe to the fundamental similarity in eukaryotic metabolism existing between fungi and humans [19] as well as a lack of fungal research initiatives and resource investment [20]. Considering this, preventative measures need to be implemented to reduce the risk of exposure to fungi in those most at risk from fungal infection. Several mycological surveillance studies have identified potential sources of contamination posing an increased risk for immunocompromised patients such as hospital construction, flower beds, and water systems [21,22,23].

This review focuses on the emergence of respiratory fungal infections with a particular focus on A. fumigatus. We highlight current and future molecular diagnostic tools for pathogen detection and surveillance. The rise in fungal respiratory infections and antifungal drug resistance mechanisms present significant challenges for health care systems. Among the respiratory diseases, Aspergillus infections are the most encountered. However, reports of non-Aspergillus, drug-resistant mould infections such as Mucormycosis, Fusarium, Scedosporium, Exophiala, and Rasamsonia are continuing to emerge in individuals at risk of fungal infections [24, 25]. Reports of fungal co-infection of the newly emerged cohort of high-risk COVID-19 patients are also of considerable clinical concern [26, 27]. Collectively, this means further research and routine surveillance is essential for understanding the epidemiology and clinical significance of emerging opportunistic fungal infections.

Fungal Respiratory Infections

Aspergillus fumigatus

Aspergillus fumigatus is a leading cause of aspergillosis and one of the most frequently occurring eukaryotes on the planet. The ubiquitous global distribution of this species has been facilitated by the aerosolisation of conidia that are able to tolerate a wide range of biotic stresses [28, 29]. It is currently estimated that more than 3 million people suffer from chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) and around 300,000 people suffer from Invasive Aspergillosis (IA) of which there is an overall 50% mortality rate [2, 30]. IA is a leading cause of death in immunocompromised patients, particularly individuals with haematological cancers and transplant patients undergoing corticosteroid therapy [31]. Currently, there are only three classes of antifungals that are recommended for use to treat aspergillosis: these are the azoles, polyenes, and echinocandins. For treatment of invasive or chronic aspergillosis the primary treatment is using the azole voriconazole, while polyenes and echinocandins are recommended as salvage therapies if the patient’s infection becomes refractory or intolerant to the primary treatment [32, 33]. In recent years, A. fumigatus has been rapidly gaining resistance to the azole drug group. Typically, azole resistant A. fumigatus (ARAf) is synonymous with substitution of specific amino acids within the cyp51A gene and the insertion of tandem repeats in the promoter region that lead its overexpression (Fig. 1) [34]. This is of great concern as the mortality rate for individuals infected with resistant isolates exceeds 80% [35, 36]. With the emergence of azole resistant phenotypes, surveillance studies are key for understanding the overall burden of azole resistance in health care settings and the environment. Genomic analysis of A. fumigatus isolates collected during nosocomial studies have identified a high prevalence of azole resistance of ~ 16% in CF patients [37] and up to 16% in soil in central London [29]. Importantly, some patients with chronic respiratory disease have never been exposed to antifungal therapy yet are infected with A. fumigatus carrying pre-adapted antifungal resistance mutations, indicating an environmental route of transmission [38]. Resistant alleles TR34/L98H and TR46/Y121F/T289A have also been shown to appears on both clonal backgrounds in the environment and in clinics [39].

It has been observed that influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis complicates the clinical progression of many patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [40,41,42]. The pulmonary epithelial damage caused by severe influenza and use of corticosteroids appear to be the main risk factors in developing IA co-infection [43, 44]. Several studies of co-infections during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009 and the Middle East Respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak in 2012 linked IA to higher mortality rates [42, 45, 46]. COVID-19 has been rapidly spreading across the world since late 2019, and to date, the number of confirmed cases exceeds 110 million people and has resulted in nearly 2.5 million deaths [47]. It has been shown that up to 40% of COVID-19 hospitalized patients can develop ARDS and are therefore potentially susceptible to co-infections caused by both bacteria and Aspergillus spp. [48,49,50]. Several reports of COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) have raised concerns that the fungal co-infection is a contributing factor to mortality [51,52,53,54] with estimates of mortality approximately 47–52% [55, 56]. Recently, published data from across Europe describe high incidence rates of 12–33% of CAPA in patients admitted to ICU with severe COVID-19 [51, 57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] and is likely to be associated with the use of corticosteroid use as a contributing risk-factor [64, 66, 67]. Given the difficulties in routine screening; overburdened health care system, handling of Hazard Group 3 samples and lack of testing capabilities, the true estimates of CAPA are likely to be grossly underestimated [66, 68, 69]. Timely surveillance and further research into the impact of Aspergillus co-infections in COVID-19 is essential for improving diagnosis, treatments, prophylaxis, and understanding the relationship with host immunological responses [66, 68].

Scedosporidium

After Aspergillus, Scedosporium ranks second as the most common fungi associated with chronic airway colonization in CF patients [70]. Molecular taxonomy has identified the most clinically relevant species as Scedosporium apiospermum, Scedosporium boydii, Scedosporium aurantiacum, Scedosporium dehoogii and Scedosporium minutisporum [71, 72]. Large variations in frequency in CF are often reported, partly due to difficulties in detection methods [73]. Positive diagnosis is largely reliant on the detection of fungal growth from clinical samples. However, the species complex is typically slow growing with an incubation period of up to 4 weeks and often out competed by high frequencies of rapidly growing fungi. [74]. The development of selective media such as SceSel + [74] and nucleic acid sequencing-based techniques [75] has vastly improved the detection of culture sensitive species. Scedosporium have shown resistance to a wide range of antifungals including polyenes (amphotericin B and nystatin) and azoles (fluconazole, itraconazole, and isavuconazole) and a reduced susceptibility to the echinocandins (caspofungin and anidulafungin) [76,77,78,79,80,81]. Furthermore, antifungal susceptibility varies between species which often makes treatment difficult [82, 83]. Species identification and susceptibility testing is highly recommended for effective treatment [81]. A draft whole genome sequence, which could be used as a reference genome, of Scedosporium boydii was only produced in 2017 [84]. Another reference genome was generated in 2020, this time of Scedosporium apiospermum [84]. While obviously a clinically relevant fungal pathogen, there is a lack of studies applying whole genome sequencing (WGS) to outbreaks of this disease, highlighting an urgent need. It is imperative that WGS is applied to other Scedosporium spp. in a bid to elucidate the mechanisms for antifungal tolerance.

Mucormycosis

Mucormycosis is a rare, aggressive infection caused by the filamentous fungi of the order Mucorales and is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality when found. Owing to the rarity of the disease, data regarding diagnosis, treatment and epidemiology are often lacking [85, 86]. The most frequent causal agents of mucormycosis include Rhizopus spp., Lichtheimia spp., Apophysomyces spp., Rhizomucor spp., Mucor spp. and Cunninghamella spp. [86, 87] and are commonly detected in patients with prolonged neutropenia and recipients of solid organ or haematopoietic stem cell transplants [88, 89]. Patients with diabetes mellitus, prolonged neutropenia and solid organ transplants are particularly at risk of developing mucormycosis infections [90]. Recently, outbreaks of mucormycosis have been reported in COVID-19 patients that have the associated risk factors diabetes mellitus and corticosteroid therapy, especially in the Indian subcontinent [27, 91,92,93]. Due to its rapid clinical progression, early diagnosis is essential for the implementation of therapeutic plans and prevention of angioinvasion and tissue necrosis [94]. However, diagnosis is limited by low culture sensitivity and often relies on the identification of hyphae in lung biopsies [90]. Furthermore, treatment can be difficult due to resistance to several of the available antifungals such as voriconazole and the echinocandins [95, 96]. Posaconazole and isavuconazole have shown in vitro efficacy but typically amphotericin B is recommended for first line therapy with possible surgical intervention [90, 97, 98]. Recently, whole genome sequencing (WGS) has been used effectively to resolve outbreaks of Mucorales spp. in hospitals. In 2019, an outbreak of mucormycosis was reported within heart and lung transplant patients over a 6 month period [99]; WGS was used to determine linkage of patients during traditional epidemiological investigations, surmising that the patients were unlikely to have been infected from a common source due to the disparate nature of the isolates. Similarly, a larger outbreak, this time of M. circinelloides f. circinelloides within a burns unit used WGS to resolve what appeared to be genotypically divergent isolates according to ITS sequencing [100]. WGS analysis provided additional insight into the nature of the outbreak, revealing that the patients were again not infected from a clonal strain, but from a pool of diverse strains in the environment. These analyses also concluded that direct transmission was also unlikely.

Fusaria

The genus Fusarium harbours important plant pathogens that are known for their wide variety of infection mechanisms [101, 102]. Opportunistically acquired Fusarium are also responsible for causing a broad spectrum of respiratory diseases in immunocompromised hosts, including allergic sinusitis [103], chronic non-invasive sinusitis [104] and disseminated infections in severely immunocompromised patients. Nosocomial surveillance studies have recovered Fusarium species from hospital water systems, and hospital air investigations into the molecular relatedness between the patient and environmental isolates identified the dispersion of conidia through showering can lead to the transmission of airborne conidia to the immunocompromised host [23]. Treatment of fusariosis, in particular infections caused by Fusarium solani, is made difficult by intrinsic resistance to many antifungal drugs, including echinocandins [105] and azoles [106, 227]. The polyene antifungal, natamycin is active against Fusarium spp. and is often used in combination with voriconazole for Fusarium-associated fungal keratitis [105, 107]. Acquired resistance mechanisms, including efflux pump overexpression and cyp51 overexpression have been linked to elevated resistance to agricultural fungicides in plant pathogenic Fusarium spp. [108] and phenotypes displaying cross-resistance to medical antifungals has been observed [109]. While WGS has been used to investigate the population structure and architecture of the Fusarium genome, this technology is yet to be applied (to the authors knowledge) to human infections. Given the large estimated global burden of Fusarium infections (approximately 1–1.2 million cases annually) [2], this is large public health concern which would benefit from applications of WGS, as demonstrated effectively in other clinical fungal infections.

Exophiala

The melanized yeast-like fungus, Exophiala dermatitidis, is a globally distributed ascomycete fungus found naturally in soil and plant debris, but also in very humid environments such as kitchens and dishwashers, where it occurs on rubber seals assisted by the formation of biofilms [110]. Generally, incidence of infection in humans caused by Exophiala spp. are uncommon, however there has been an increase in the reporting of E. dermatitidis as a causative agent of human disease in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts [111,112,113,114,115]. Infections that are caused by E. dermatitidis can be subdivided into three groups: superficial, cutaneous and subcutaneous, and systemic or visceral. Superficial infections often relate to surgical operation or trauma and non-superficial infections occur in patients with predisposing illness [116]. CF patients have displayed a high rate of E. dermatidis where it can be commonly found in respiratory tracts [117] and is thought to be pathogenic [118] Identification of Exophiala spp. is commonly established through the isolation of strains using either Sabouraud agar (SAB) or erythritol chloramphenicol agar (ECA), followed by sequencing of the fungal-specific ITS marker regions (ITS1, ITS2) [119]. Very little is known about the true susceptibility status of Exophiala spp. to antifungal agents, however these infections appear to be susceptible to a range of azoles including voriconazole, itraconazole, and posaconazole, but show reduced susceptibility to echinocandins and fluconazole [119, 120].

While the Exophiala species complex is large, a considerable number of studies have applied WGS to both environmental and clinical Exophiala isolates. Notably, a study produced in 2020 analysed both the genomes and transcriptomes of E. dermatitidis isolates, indicating that some strains of this species are able to alter their transcriptomes to cope with moderate stress, before returning to the original state [121]. This could provide a mechanism of adaptation to the human host. This was corroborated by an additional study using long read sequencing and transcriptomics, revealing adaptive strategies within E. spinifera. It is possible that Exophiala spp. are therefore able to adapt to habitat choice and cause infection in susceptible patient populations. Future studies employing WGS, in addition to transcriptomics, will be useful to explore these adaptive strategies and mechanisms of pathogenicity further [122].

Cryptococcus gattii/neoformans species complexes

Pulmonary cryptococcosis is a lung infection that may cause acute pneumonia progressing to ARDS and, if dissemination occurs, fungal meningitis. The disease is caused by encapsulated yeasts C. neoformans/gattii that belong to the phylum Basidomycota. These yeasts are commonly found associated with trees, animals, birds, and their faeces and cause infection following inhalation. In the lower airways, pulmonary macrophages engulf and kill Cryptococcus however in some cases (often associated with risk factors such as HIV-AIDs), yeasts can survive to cause pulmonary infection, ARDS and onwards dissemination to the meninges [123]. Radiological diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis is difficult as the inflammatory changes and nodules are similar to those associated with other infections including mycobacteria and viruses, as well as malignancies. Laboratory diagnosis of the infection traditionally relies on visualizing the characteristic encapsulated yeasts in respiratory samples or direct culture. However, detection of cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) using lateral flow tests has recently revolutionized the diagnosis of this disease in a variety of clinical settings.

The use of genomics has been key to our understanding of the epidemiology of cryptococcosis and has a substantial body of literature owing to the use of genomics in this area. The use of WGS from serially collected isolates of C. neoformans was integral for determining whether HIV/AIDS patients were undergoing recurrence of infection due to relapse of the original infecting isolate, or re-infection with a different isolate. The study by Rhodes et al. [124], demonstrated that patients were most likely experiencing recurrent infections due to a relapse of the original infecting isolate, due to the clonal relationship and low genetic diversity between serially collected isolates. However, this study also utilized WGS to show that some isolates displaying high levels of genetic heterogeneity due to nonsense mutations within MSH2, the gene encoding DNA mismatch repair, leading to a hypermutator state, allowing evolution to antifungal drugs. Further, experimental studies have confirmed that the hypermutator state within the closely related Cryptococcus deuterogattii also allows within-host adaptation [125]; it is therefore plausible that the C. neoformans hypermutator state could similarly lead to within-host adaptation.

Later, studies using serially collected C. neoformans isolates have investigated the evolution to antifungal drugs further; a study by Stone et al. [126] used WGS to conclude that aneuploidy within C. neoformans drives heteroresistance to fluconazole-only drug therapy. This finding is clinically relevant and has real-world implications in the treatment of cryptococcosis, which encourages the use of combination drug therapy.

Genomics has also proved useful when investigating outbreak of C. neoformans; an outbreak in a Glaswegian hospital in 2018 was investigated with genomic epidemiology and found that isolates were genetically distinct. Genomic analyses were crucial to identifying that patients likely acquired the infection independently, rather than direct transmission of a clonal isolate [127].

Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP)

Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) is a serious respiratory infection caused by the yeast-like fungus Pneumocystis jirovecii. It is the major causative agent of a life-threatening pneumonia in immunosuppressed patients [128, 129]. Incidence of P. jirovecii infection in healthy people ranges between 0 and 20% [130]; although lung autopsies of individuals that died accidentally, followed by a nested PCR approach, found that an asymptomatic P. jirovecii pulmonary infection is prevalent in more than half of the general population [131].

Pneumocystis jirovecii infection becomes much more serious in patients with prior medical conditions that has weakened their immune system. Notably, the prevalence of PCP suddenly spiked in the 1980s in homosexual men in the USA, trigging the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco, prior to the identification of HIV [132]. PCP is now often described as the AIDS-defining illness in patients with HIV [133]. Typically, 40–75% of AIDS patients will acquire PCP at some stage during their illness [134, 135]. The use of antiviral drugs, in combination with effective prophylaxis using trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole [133] has decreased the incidence and mortality rate, resulting in reports of a significantly higher mortality rate for immunosuppressed non-AIDS patients when compared to AIDS patients [135, 136]. Nevertheless, reports of resistance to trimethoprim, facilitated by mutations in the drugs target, have been identified in patients with PCP, raising concerns about their continued effectiveness [137].

The draft of P. jirovecii genome was first sequenced in 2012 from a single bronchoalveolar lavage of a patient with pneumonia [138]. However, the contiguous construction of this genome was limited due to sequence repetition, including large expansions of gene families encoding major surface glycoproteins [128]. More recently, high depth short read sequencing and long read sequencing have been utilized to improve the resolution of the P. jirovecii genomes [128, 129, 139]. Using comparative genomics of Pneumocystis spp. that infect humans and rodents, mechanisms of adaptation have been identified that allow the pathogen to thrive in mammalian hosts and evade both the innate and acquired immune defences [128]. For example, using gene-prediction tools and biochemical assays, one study has shown that Pneumocystis spp. lack two key fungal cell wall components: chitin and outer chain N-mannans, which may allow the organism to evade host defences [128]. Moreover, population level genome resequencing has also shown that natural populations of P. jjrovecii are widely distributed and display high genetic diversity, despite being associated predominantly with mammalian lung environments. This diversity may provide a selective advantage in avoiding detection of the host immune system [140].

Current Diagnostic Methods Available

Current Non-Molecular Clinical Diagnostics

Respiratory fungal diseases remain hard to diagnose in patients that are immunocompromised as it is often difficult to differentiate between fungal species that cause pulmonary infections through radiography [141]. For identification of invasive fungal infections, histopathology is considered one of the criteria for diagnosis [142]. However, histopathology may require the biopsy of deep tissues which exposes immunosuppressed patients to a high level of risk of infection [143]. Therefore, conventional diagnostic techniques such as culture and phenotypic analysis are regularly used to confirm Aspergillus spp., Cryptococcus spp., Fusarium spp., and Scedosporeium spp. [144] as well as to detect antifungal resistance in sputum from patients [145]. However, due to the poor sensitivity of fungal cultures, and multiple resistance phenotypes requiring multiple resistance testing, a relatively high level of mycology training is required for accurate diagnosis. Culture methods also take several days to yield any results [146] and epidemiological cut-off point, at which there is a relationship between in vitro azole susceptibility in fungal culture and clinical outcomes, have also been shown to be unclear [147]. Serum antigen assays are a more sensitive non-molecular diagnostic which can be used in conjunction with culture techniques to flag for fungal infections [146]. Such examples include assays for the biomarker β-d-glucan, a major component in the fungal cell wall [148] and assays for galactomannan, a polysaccharide released by Aspergillus spp. during growth [149]. β-D-Glucan can be found in the sera of patients infected by Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp., and Pneumocystis spp., and therefore although sensitive these assays are not specific [146]. β-d-Glucan assays are also unable to detect Mucor or Rhizopus species as they do not have β-D-Glucan within their cell walls [150]. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) that target fungal-specific IgG have also been developed to detect fungal infection from patient samples [151, 152]. Although ELISA leads to quicker diagnosis than culture methods, antibody detection methods can have low specificity and associate with other closely related fungal species. Another limitation is that immunosuppressed patients, who are some of the most susceptible individuals to fungal respiratory disease, will show reduced sensitivity for these assays and do not test for antifungal resistance [153]. Therefore, as azole resistance in filamentous fungi such as A. fumigatus continues to emerge worldwide [154], the need for rapid and specific diagnostics using molecular-based detection becomes more apparent. Consequently, this has accelerated the development of molecular diagnostics for the detection of azole resistance in culture-negative patients.

Current Molecular Diagnostics

When using PCR to detect A. fumigatus within a sample, common PCR targets that are used include the 18S rRNA gene, 28S rRNA gene and the internal transcribed spacers (ITS) [155]. Combining PCR and Sanger sequencing of cyp51A can detect drug resistance mutations. An advantage of using PCR over fungal culture is therefore the ability to simultaneously and quickly screen clinical samples for both A. fumigatus DNA and for mutations that are associated with azole resistance. This can be done by using multiplex PCRs which are able to detect multiple clinically relevant Aspergillus species in one assay [156]. For example, the commercially available MycoGENIE A. fumigatus real-time PCR kit detects the 28S rRNA gene as well as TR34 and L98H mutations that are associated with azole resistance within the cyp51A gene [157]. As well as the MycoGENIE A. fumigatus kit there are also several other commercial products available for the detection of ARAf, such as PathoNostics AsperGenius assay (PathoNostics, Maastricht, Netherlands) and Fungiplex® Aspergillus Azole-R in vitro diagnostics (IVD) PCR (Bruker Daltonik 75 GmbH, Bremen, Germany). However, the most recent guidelines suggest that diagnostic PCR is only used on a case-by-case basis in clinical practice. This is due to the lack of conclusive validation of commercially available assays, and the range of different methodologies currently found within literature [33]. To try and face this issue, the European Aspergillus PCR initiative (EAPCRI) was founded, with the aim to begin and standardize Aspergillus PCR methodology and validate PCR methodologies in clinical trials [158]. PCR kits have also shown poor sensitivity for detection of azole resistance directly on sputum samples and therefore still require the need for culture [159].

As is with Aspergillus spp., detection of fungal DNA as a means of diagnostics is a tempting approach for detection of other respiratory fungal diseases. This is especially true for infections such as P. jirovecii which cannot be cultured, and diagnosis is traditionally based using staining methods or fluorescent microscopy. However, these methods can often be subjective leading to low sensitivity [160]. In contrast, PCR of PCP respiratory specimens have shown as high sensitivity as 100% and can play an important role in the early diagnostics of PCP [161]. However, standard PCR cannot distinguish between airway colonization by P. jirovecii and pneumonia.This is a considerable challenge as sub-clinical Pneumocystis airway colonization occurs in up to 22% of high-risk patients and therefore the significance of a positive PCR test may be dubious [162]. This obstacle was overcome after it was found that PCP patients had a substantially higher concentrations of Pneumocystis DNA within Broncho Alveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) when compared to individuals with colonization or sub-clinical infection [163]. This allows for the fungal burden to be estimated from cycle threshold values obtained through qualitative PCR in order to differentiate between pneumonia and sub-clinical infection [164]. Furthermore, commercial qPCR assays have been developed by PathNostics (Maastricht, Netherlands) to aid the detection of Pneumocystosis directly from BAL samples with high sensitivity and a sample to result in less than 3 h.

Diagnosis of mucormycosis can also benefit from PCR as Mucorales which are difficult to culture. Mucorales are also often mistaken for A. fumigatus in histopathology, and there are no serological tests that are commercially available [90, 165, 166]. An attractive approach is to test for Mucorales DNA in BALF or serum using PCR. Several retrospective studies, using three qPCR assays to target 18S rDNA in rhizomucor, Mucor/Rhizopus and Lichtheimia within patient serum samples, have shown Mucorales DNA can be detected on average 9 days (up to 68 days) before mucormycosis could be confirmed by culture or histopathology and up to 3 days before radiographic features were observed on CT scans [167, 168]. Currently, PCR assays cannot be used cannot be recommended as diagnosis of mucormycosis without culture and/or histological evidence [166]; however, it is hoped that with the commercial release of real-time PCR assays for the detection of clinically relevant Mucor species by PathoNostics (MucorGenius; Maastricht, Netherlands) will start to standardize assays between clinical laboratories.

PCR diagnostic techniques have also been developed to detect other fungal diseases that cause respiratory infection including Fusarium spp. [169], Scedosporium spp. [170], and Exophiala spp. [171]. However, analysis of larger numbers of patient samples are still needed to assess the prevalence of these assays in clinical samples before they can be accepted for regular clinical diagnostics in the near future. Nested PCR has also been designed Cryptococcus spp. [172] however as there are already serologic assays which have high specificity and sensitivity for Cryptococcus spp. [173], reducing the urgency for clinical molecular diagnostics.

Future Directions

Loop Mediated Isothermal AMPlification (LAMP)

PCR is often still viewed as the gold standard for quick diagnosis of fungal respiratory pathogens. However, PCR needs to be conducted in a well-equipped laboratory setting with trained personnel and can therefore not be easily deployed at a point-of-care or in an environmental setting [174]. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) offers an attractive alternative to PCR as it does not require temperature cycling and shows both high speed and specificity [175]. LAMP is a one-step isothermal amplification reaction which uses a DNA polymerase with a high strand displacement activity and four specific primers (two internal and two external), to produce an amplicon with a cauliflower-like structure [176]. The addition of loop primers is also able to significantly reduce the LAMP amplification time, by up to 30 min [177]. Recently, a LAMP-based assay was developed that can detect A. fumigatus containing the TR34 and TR46 azole resistance allele with high sensitivity, positively detecting down to 10 genomic copies/reaction in under 30 min [178, 179]. This assay was developed so it could be performed on a “lab-on-chip” platform, a diagnostic platform which uses a silicon nitride layer to bind protons released during the incorporation of nucleic acids into DNA to track DNA amplification. This data can then be sent to a smartphone device via Bluetooth which theoretically allows for easy use at a point-of-care. The application of LAMP has also been incorporated into the detection other clinically significant fungi such as Exophiala and Scedosporium species [180]. It has also been shown to be an effective point-of-care tool for Chagas disease [181] and Salmonella [182] and is being developed and used extensively throughout the COVID-19 pandemic to identify infections early and prevent the spread of the disease [183,184,185]. The only main disadvantages of LAMP are that the primers used in the assay need to be kept cold while working in the field, and even though the assay itself is easy to operate, the design of the primers themselves for detection of specific species and alleles requires expertise and detailed understanding of the target pathogen genome [174].

Whole Genome Sequencing

Next generation sequencing technologies have allowed whole genome sequencing (WGS) to become a valuable tool within the field of mycology. WGS allows for entire genome sequencing at a cost comparable to traditional methods, such as multi-locus sequencing typing (MLST) [186]. However, MLST techniques and short tandem repeat (STR) assay methods, do still provide a fast, reproducible, inexpensive and easy method of examining population genetics of a large quantity of isolates [187]. Case in point, researchers recently analysed the genetic relatedness of 4,089 A. fumigatus isolates from a worldwide collection, genotyped at 9 microsatellite locations, to demonstrate, through hierarchical clustering that the species population could be divided into two clades [154]. Resistant genotypes TR34/L98H and TR46/Y121F/T289A were found to be unevenly distributed across the clades and showed to have less diverse genetic backgrounds than wild-type isolates, with identical clonal isolates being found worldwide. To allow clinicians and researchers to make informed decisions on drug administration and epidemiological infection studies this analysis has now been incorporated into a free interactive R shiny application (AfumID) to permit quick characterization of A. fumigatus isolates. However, WGS is becoming the method of choice for molecular epidemiological studies due to the high resolution of data it generates, at a comparatively low labour and monetary expense [188]. The application of WGS is not just limited to genotyping clinical and environmental genomes but can be used in screening for antifungal resistance, analysing of patterns of natural selection and gene flow in nature and addressing developing outbreaks of respiratory fungal diseases [189,190,191]. The recent development of sequencing devices such as the Oxford MinION nanopore sequencing has allowed for the rapid real-time sequencing of epidemics in resource limiting settings, which have been fully utilized in bacterial and viral outbreaks [192,193,194]. Real-time sequencing of fungal pathogens has also been attempted and could prove to be a promising tool to monitor future outbreaks [195]. As with other sequencing technologies, nanopore sequencing does not require previous knowledge of a pathogens genome and can be used to help construct reference genomes [196]. Coupled with its ease of portability (weighing less than 100 g) enabling quicker response times, detection of potentially unknown pathogens and can be used at point of care or in the field as demonstrated for Ebola and Zika [193, 194, 197], although it should be noted that even though the sequencing device is portable other consumables and laboratory equipment will be needed for DNA extraction. In 2018, the largest outbreak of Candida auris in the UK at the time was retrospectively analysed using nanopore sequencing for rapid WGS to examine the genomic epidemiology. WGS established that resistance was unlikely to have developed from multiple sources and identified isolates that had reduced susceptibility to specific antifungal drugs [191]. This was the first time that the nanopore sequencing had been used on a human fungal pathogen and the techniques illustrated here could be transferred to allow analysis of future outbreaks of human respiratory fungal pathogens. However, one of the potential difficulties that may be encountered when using nanopore for sequencing of A. fumigatus is that mould gDNA is prone to fragmentation [198]. Therefore, DNA extraction may first need to be optimized to in order to overcome this.

Nanopore sequencing and other WGS technologies can also be used for outbreak management, which was demonstrated in another C. auris outbreak within an intensive care unit (ICU) in Oxford (U.K.). Genomic analyses in this study confirmed that C. auris isolates on equipment within the hospital were more closely related to those collected from patients. This led to the removal of reusable temperature probes which was subsequently followed by a reduction in patient infection and control of the outbreak [199].

WGS has been increasingly used within mycology for sequencing of different Aspergillus species. One of its most beneficial uses is the ability to detect mutations within the cyp51A gene which are associated with A. fumigatus resistance to azoles and therefore can be used to predict drug resistance to first line therapies within a clinical setting [200]. WGS can also be used to enable high-resolution single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) analysis to observe evolution and selection for antifungal resistance and potentially uncover new mechanisms of resistance [188]. Whole genome comparisons of 13 A. fumigatus strains with increasing azole resistance, collected from a single patient undergoing azole and echinocandin combination therapy, over a 2-year period identified 248 non-synonymous SNPs [201]. Of the isolates, nine were shown to have acquired SNPs within the cyp51A gene, likely as a result of azole induced pressure. However, in most of these isolates, the cyp51A SNPs did not fully explain the resistance profiles that were observed therefore suggests that the presence of some non-cyp51A SNPs are partially responsible for mediating azole tolerance through novel mechanisms [201].

Metagenomics

The advent of next generation sequencing (NGS) has also allowed for metagenomic approaches to become an emerging option for clinical diagnosis. Unlike most molecular assays used for diagnosis of infectious disease, which only target a limited number of pathogens with specific primers/probes, approaches such as untargeted metagenomic NGS use shotgun sequencing to survey a proportion of DNA and/or RNA from within a sample without bias. Theoretically, using this method, in a single assay nearly all bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses can be identified within a sample [202]. However, when using this method typically < 1% of reads will be non-human of which only a subset will correspond to the causative pathogen [203]. Therefore, targeted approaches can be used to increase the proportion of reads from pathogens within the sequence data. This can be done by using primers for a highly conserved region, such as 18S ribosomal RNA, TEF1α and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) in fungi, for universal PCR amplification and then using NGS of the amplicon to identify potential pathogens [204]. However, before metagenomic techniques can be adopted to identify fungal pathogens in clinical samples, there are several factors which cause inaccuracies that must first be overcome. These include pre-PCR biases that occur during DNA extraction due to contamination or choice of extraction kits or storage buffers and PCR biases caused by varying lengths of amplicons or primer mismatches [205]. Another limitation is the lack of a well-curated reference databases with correct taxonomic for fungal species, this can lead to misidentification and cross-talk between fungal sequences [206]. Clinical metagenomics is also exceedingly expensive to setup and could cost up to one million pounds once computer infrastructure, personnel and sequencing facilities have been considered [207].

Communication

With new genome sequencing projects being able to produce vast quantities of sequencing data, it is crucial that genomic data is deposited in short read archives with associated metadata so that data can be synthesized across sequencing projects in order to accelerate genomic epidemiologic analysis [208]. It is also important that data can be presented in a format that will be understood by a large ranging audience [209]; This has led to the development of flexible web-browser enabled applications such as Microreact [209] which is able to display phylogeographical and temporal representation of fungal genomic analysis within the context of its own metadata, and allows for the data to be interactively visualized in the form of maps, phylogenetic trees and timelines.

Concluding Remarks

Significant advances in fungal genomics in recent years have undoubtably enhanced the future of nucleic acid diagnostic technologies in the field of fungal respiratory disease. Currently, conventional diagnostic techniques such as culture, microscopy and phenotypic analysis are still recommended for clinical diagnosis of fungal respiratory diseases [33]. However, molecular diagnostics and sequencing technologies offer a reproducible, cost-effective option for generating rapid data that can accelerate the epidemiology of mycoses. These technologies will increasingly be used more for medical diagnosis of fungal infections as their use within clinical laboratories increases and methodologies become standardized (Fig. 2).

References

Bongomin F, Gago S, Oladele RO, Denning DW. Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases—estimate precision. J Fungi. 2017;3:57.

Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NAR, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. Hidden killers: Human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:165rv13.

Rauseo AM, Coler-Reilly A, Larson L, Spec A. Hope on the horizon: novel fungal treatments in development. Open forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa016.

Richardson MD. Changing patterns and trends in systemic fungal infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:i5-11.

Blyth CC, Middleton PG, Harun A, Sorrell TC, Meyer W, Chen SCA. Clinical associations and prevalence of Scedosporium spp. in Australian cystic fibrosis patients: Identification of novel risk factors? Med Mycol. 2010;48:Sz37–44.

Chotirmall SH, O’Donoghue E, Bennett K, Gunaratnam C, O’Neill SJ, McElvaney NG. Sputum Candida albicans presages FEV1 decline and hospital-treated exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2010;138:1186–95.

Kondori N, Gilljam M, Lindblad A, Jönsson B, Moore ERB, Wennerås C. High rate of Exophiala dermatitidis recovery in the airways of patients with cystic fibrosis is associated with pancreatic insufficiency. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1004–9.

Dagenais TRT, Keller NP. Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in invasive aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:447–65.

Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: Outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:531–40.

Khalafallah A, Maiwald M, Hannan T, Abell S, Staker J, Supperamohan A. Early implementation of antifungal therapy in the management of febrile neutropenia is associated with favourable outcome during induction chemotherapy for acute leukaemias. Intern Med J. 2012;42:131–6.

Morrell M, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. Delaying the empiric treatment of Candida bloodstream infection until positive blood culture results are obtained: A potential risk factor for hospital mortality. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3640–5.

Garey KW, Rege M, Pai MP, Mingo DE, Suda KJ, Turpin RS, et al. Time to initiation of fluconazole therapy impacts mortality in patients with candidemia: A multi-institutional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:25–31.

Zhang J, Snelders E, Zwaan BJ, Schoustra SE, Meis JF, Van Dijk K, et al. A novel environmental azole resistance mutation in Aspergillus fumigatus and a possible role of sexual reproduction in its emergence. MBio. 2017;8.

Faria-Ramos I, Farinha S, Neves-Maia J, Tavares PR, Miranda IM, Estevinho LM, et al. Development of cross-resistance by Aspergillus fumigatus to clinical azoles following exposure to prochloraz, an agricultural azole. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:1–5.

Snelders E, Camps SMT, Karawajczyk A, Schaftenaar G, Kema GHJ, van der Lee HA, et al. Triazole fungicides can induce cross-resistance to medical triazoles in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31801.

Chowdhary A, Kathuria S, Xu J, Meis JF. Emergence of Azole-Resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains due to Agricultural Azole use creates an increasing threat to human health. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003633.

Du Pré S, Beckmann N, Almeida MC, Sibley GEM, Law D, Brand AC, et al. Effect of the novel antifungal drug F901318 (olorofim) on growth and viability of Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62.

Berman J, Krysan DJ. Drug resistance and tolerance in fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:319–31.

Perfect JR. The antifungal pipeline: A reality check. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:603–16.

Fisher MC, Hawkins NJ, Sanglard D, Gurr SJ. Worldwide emergence of resistance to antifungal drugs challenges human health and food security. Science (80-. ). American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2018. p. 739–42.

Kanamori H, Rutala WA, Sickbert-Bennett EE, Weber DJ. Review of fungal outbreaks and infection prevention in healthcare settings during construction and renovation. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:433–44.

Godeau C, Reboux G, Scherer E, Laboissiere A, Lechenault-Bergerot C, Millon L, et al. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in the hospital: Surveillance from flower beds to corridors. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:702–4.

Anaissie EJ, Kuchar RT, Rex JH, Francesconi A, Kasai M, Müller FMC, et al. Fusariosis associated with pathogenic Fusarium species colonization of a hospital water system: A new paradigm for the epidemiology of opportunistic mold infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1871–8.

Salehi E, Hedayati MT, Zoll J, Rafati H, Ghasemi M, Doroudinia A, et al. Discrimination of aspergillosis, mucormycosis, fusariosis, and scedosporiosis in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue specimens by use of multiple real-time quantitative PCR assays. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:2798–803.

Park BJ, Pappas PG, Wannemuehler KA, Alexander BD, Anaissie EJ, Andes DR, et al. Invasive non-Aspergillus mold infections in transplant recipients, United States, 2001–2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1855.

Hoenigl M, Salmanton-García J, Walsh TJ, Nucci M, Neoh CF, Jenks JD, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of rare mould infections: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology and the American Society for Microbiolo. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021

Hoenigl M, Seidel D, Carvalho A, Rudramurthy SM, Arastehfar A, Gangneux JP, et al. The Emergence of COVID-19 Associated Mucormycosis: Analysis of Cases From 18 Countries. SSRN Electron J. 2021.

Pringle A, Baker DM, Platt JL, Wares JP, Latgé JP, Taylor JW. Cryptic speciation in the cosmopolitan and clonal human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Evolution (N Y). 2005;59:1886–99.

Sewell TR, Zhang Y, Brackin AP, Shelton JMG, Rhodes J, Fisher MC. Elevated prevalence of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in urban versus rural environments in the United Kingdom. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. American Society for Microbiology; 2019;63.

Osherov N, Kontoyiannis DP. The anti-Aspergillus drug pipeline: is the glass half full or empty? Sabouraudia. 2016;55:118–24.

Fukuda T, Boeckh M, Carter RA, Sandmaier BM, Maris MB, Maloney DG, et al. Risks and outcomes of invasive fungal infections in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood Am Soc Hematol. 2003;102:827–33.

Dockrell DH. Salvage therapy for invasive aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:i41–4.

Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e1-60.

Rivero-Menendez O, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Mellado E, Cuenca-Estrella M. Triazole resistance in Aspergillus spp.: a worldwide problem? J Fungi. 2016;2:21.

Steinmann J, Hamprecht A, Vehreschild M, Cornely OA, Buchheidt D, Spiess B, et al. Emergence of azole-resistant invasive aspergillosis in HSCT recipients in Germany. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:1522–6.

Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Kathuria S, Hagen F, Meis JF. Prevalence and mechanism of triazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus in a referral chest hospital in Delhi, India and an update of the situation in Asia. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:428.

Abdolrasouli A, Scourfield A, Rhodes J, Shah A, Elborn JS, Fisher MC, et al. High prevalence of triazole resistance in clinical Aspergillus fumigatus isolates in a specialist cardiothoracic centre. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52:637–42.

Dauchy C, Bautin N, Nseir S, Reboux G, Wintjens R, Le Rouzic O, et al. Emergence of Aspergillus fumigatus azole resistance in azole-naïve patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their homes. Indoor Air. 2018;28:298–306.

Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Meis JF. Azole-resistant aspergillosis: Epidemiology, molecular mechanisms, and treatment. J Infect Dis. 2017;216:S436–44.

Alobaid K, Alfoudri H, Jeragh A. Influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in a patient on ECMO. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2020;27:36–8.

Vehreschild JJ, Bröckelmann PJ, Bangard C, Verheyen J, Vehreschild M, Michels G, et al. Pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection coinciding with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in neutropenic patients. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:1848–52.

Schauwvlieghe AFAD, Rijnders BJA, Philips N, Verwijs R, Vanderbeke L, Van Tienen C, et al. Invasive aspergillosis in patients admitted to the intensive care unit with severe influenza: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:782–92.

Lat A, Bhadelia N, Miko B, Furuya EY, Thompson GR. Invasive aspergillosis after pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:971–3.

Wauters J, Baar I, Meersseman P, Meersseman W, Dams K, De Paep R, et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is a frequent complication of critically ill H1N1 patients: A retrospective study. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1761–8.

Ku YH, Chan KS, Yang CC, Tan CK, Chuang YC, Yu WL. Higher mortality of severe influenza patients with probable aspergillosis than those with and without other coinfections. J Formos Med Assoc. 2017;116:660–70.

Van De Veerdonk FL, Kolwijck E, Lestrade PPA, Hodiamont CJ, Rijnders BJA, Van Paassen J, et al. Influenza-associated aspergillosis in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:524–7.

Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:533–4.

Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk Factors Associated with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan. China JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:934–43.

Chen X, Zhao B, Qu Y, Chen Y, Xiong J, Feng Y, et al. Detectable serum severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 viral load (RNAemia) is closely correlated with drastically elevated interleukin 6 level in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:1937–42.

Zhu X, Ge Y, Wu T, Zhao K, Chen Y, Wu B, et al. Co-infection with respiratory pathogens among COVID-2019 cases. Virus Res. 2020;285:198005.

Koehler P, Cornely OA, Böttiger BW, Dusse F, Eichenauer DA, Fuchs F, et al. COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2020;63:528–34.

Arastehfar A, Carvalho A, van de Veerdonk FL, Jenks JD, Koehler P, Krause R, et al. COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA)—from immunology to treatment. J Fungi. 2020;6:91.

Nasir N, Farooqi J, Mahmood SF, Jabeen K. COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) in patients admitted with severe COVID-19 pneumonia: An observational study from Pakistan. Mycoses. 2020;63:766–70.

Koehler P, Bassetti M, Chakrabarti A, Chen SCA, Colombo AL, Hoenigl M, et al. Defining and managing COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: the 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus criteria for research and clinical guidance. Lancet Infect Dis: Elsevier; 2020.

Meijer EFJ, Dofferhoff ASM, Hoiting O, Meis JF. COVID‐19‐associated pulmonary aspergillosis: a prospective single‐center dual case series. Mycoses. 2021;1–8.

Salmanton-García J, Sprute R, Stemler J, Bartoletti M, Dupont D, Valerio M, et al. COVID-19-Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis, March-August 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1077.

White PL, Dhillon R, Cordey A, Hughes H, Faggian F, Soni S, et al. A National Strategy to Diagnose Coronavirus Disease 2019–Associated Invasive Fungal Disease in the Intensive Care Unit. Clin Infect Dis. 2020.

Borman AM, Palmer MD, Fraser M, Patterson Z, Mann C, Oliver D, et al. COVID-19-associated invasive aspergillosis: Data from the UK national mycology reference laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59.

van Arkel ALE, Rijpstra TA, Belderbos HNA, van Wijngaarden P, Verweij PE, Bentvelsen RG. COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:132–5.

Van Biesen S, Kwa D, Bosman RJ, Juffermans NP. Detection of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in COVID-19 with nondirected BAL. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:1171–3.

Rutsaert L, Steinfort N, Van Hunsel T, Bomans P, Naesens R, Mertes H, et al. COVID-19-associated invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:1–4.

Bartoletti M, Pascale R, Cricca M, Rinaldi M, Maccaro A, Bussini L, et al. Epidemiology of Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis Among Intubated Patients With COVID-19: A Prospective Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;

Dupont D, Menotti J, Turc J, Miossec C, Wallet F, Richard J-C, et al. Pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Med Mycol. 2021;59:110–4.

Alanio A, Dellière S, Fodil S, Bretagne S, Mégarbane B. Prevalence of putative invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e48–9.

Helleberg M, Steensen M, Arendrup MC. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:147–8.

Armstrong-James D, Youngs J, Bicanic T, Abdolrasouli A, Denning DW, Johnson E, et al. Confronting and mitigating the risk of COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Eur Respir J. 2020;56.

Chauvet P, Mallat J, Arumadura C, Vangrunderbeek N, Dupre C, Pauquet P, et al. Risk Factors for Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Critically Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019-Induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Explor. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2020;2:e0244.

Verweij PE, Alanio A. Fungal infections should be part of the core outcome set for COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;

Thompson GR, Cornely OA, Pappas PG, Patterson TF, Hoenigl M, Jenks JD, et al. Invasive aspergillosis as an under-recognized superinfection in COVID-19. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa242.

Cimon B, Carrère J, Vinatier JF, Chazalette JP, Chabasse D, Bouchara JP. Clinical significance of Scedosporium apiospermum in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:53–6.

Rougeron A, Giraud S, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cano-Lira J, Rainer J, Mouhajir A, et al. Ecology of Scedosporium Species: Present knowledge and future research. Mycopathologia. 2018;183:185–200.

Chen M, Zeng J, De Hoog GS, Stielow B, Gerrits Van Den Ende AHG, Liao W, et al. The “species complex” issue in clinically relevant fungi: A case study in Scedosporium apiospermum. Fungal Biol. 2016;120:137–46.

Bouchara JP, Le Govic Y, Kabbara S, Cimon B, Zouhair R, Hamze M, et al. Advances in understanding and managing Scedosporium respiratory infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2020;14:259–73.

Blyth CC, Harun A, Middleton PG, Sleiman S, Lee O, Sorrell TC, et al. Detection of occult scedosporium species in respiratory tract specimens from patients with cystic fibrosis by use of selective media. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:314–6.

Lu Q, van den Ende AHGG, Bakkers J, Sun J, Lackner M, Najafzadeh MJ, et al. Identification of Pseudallescheria and Scedosporium species by three molecular methods. J Clin Microbiol Am Soc Microbiol. 2011;49:960–7.

Cuenca-Estrella M, Ruiz-Díez B, Martínez-Suárez JV, Monzón A, Rodríguez-Tudela JL. Comparative in-vitro activity of voriconazole (UK-109,496) and six other antifungal agents against clinical isolates of Scedosporium prolificans and Scedosporium apiospermum. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:149–51.

Sedlacek L, Graf B, Schwarz C, Albert F, Peter S, Würstl B, et al. Prevalence of Scedosporium species and Lomentospora prolificans in patients with cystic fibrosis in a multicenter trial by use of a selective medium. J Cyst Fibros. 2015;14:237–41.

Gilgado F, Serena C, Cano J, Gené J, Guarro J. Antifungal susceptibilities of the species of the Pseudallescheria boydii complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:4211–3.

Carrillo AJ, Guarro J. In vitro activities of four Novel Triazoles against Scedosporium spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2151–3.

Lackner M, De Hoog GS, Verweij PE, Najafzadeh MJ, Curfs-Breuker I, Klaassen CH, et al. Species-specific antifungal susceptibility patterns of Scedosporium and Pseudallescheria species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2635–42.

Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, van Diepeningen A, Caira M, Munoz P, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:27–46.

Lackner M, Klaassen CH, Meis JF, van den Ende AHGG, De Hoog GS. Molecular identification tools for sibling species of Scedosporium and Pseudallescheria. Sabouraudia. 2012;50:497–508.

Schwarz C, Brandt C, Melichar V, Runge C, Heuer E, Sahly H, et al. Combined antifungal therapy is superior to monotherapy in pulmonary scedosporiosis in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18:227–32.

Duvaux L, Shiller J, Vandeputte P, de Bernonville TD, Thornton C, Papon N, et al. Draft genome sequence of the human-pathogenic fungus Scedosporium boydii. Genome Announc. 2017;5.

Prakash H, Chakrabarti A. Global epidemiology of mucormycosis. J Fungi. 2019;5:26.

Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, Knudsen TA, Sarkisova TA, Schaufele RL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: A review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634–53.

Jeong W, Keighley C, Wolfe R, Lee WL, Slavin MA, Kong DCM, et al. The epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case reports. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:26–34.

Farmakiotis D, Kontoyiannis DP. Mucormycoses. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:143–63.

Chamilos G, Marom EM, Lewis RE, Lionakis MS, Kontoyiannis DP. Predictors of pulmonary zygomycosis versus invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:60–6.

Cornely OA, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Arenz D, Chen SCA, Dannaoui E, Hochhegger B, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Lancet Infect Dis Elsevier. 2019;19:e405–21.

Mehta S, Pandey A. Rhino-orbital mucormycosis associated with COVID-19. Cureus. Cureus Inc.; 2020;12.

Werthman-Ehrenreich A. Mucormycosis with orbital compartment syndrome in a patient with COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;42:264.e5-264.e8.

Khan N, Gutierrez CG, Martinez DV, Proud KC. A case report of COVID-19 associated pulmonary mucormycosis. Arch Clin Cases. 2021;7:2020–7.

Chamilos G, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Delaying amphotericin B-based frontline therapy significantly increases mortality among patients with hematologic malignancy who have zygomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:503–9.

Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Castelli MV, Cuesta I, Zaragoza O, Monzón A, Mellado E, et al. In vitro activity of antifungals against zygomycetes. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:71–6.

Guinea J, Peláez T, Recio S, Torres-Narbona M, Bouza E. In vitro antifungal activities of isavuconazole (BAL4815), voriconazole, and fluconazole against 1,007 isolates of zygomycete, Candida, Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Scedosporium species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1396–400.

Tissot F, Agrawal S, Pagano L, Petrikkos G, Groll AH, Skiada A, et al. ECIL-6 guidelines for the treatment of invasive candidiasis, aspergillosis and mucormycosis in leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Haematologica. 2017;102:433.

Brunet K, Rammaert B. Mucormycosis treatment: recommendations, latest advances, and perspectives. J Mycol Med. 2020;101007.

Marek C, Croxen MA, Dingle TC, Bharat A, Schwartz IS, Wiens R, et al. The use of genome sequencing to investigate an outbreak of hospital‐acquired mucormycosis in transplant patients. Transpl Infect Dis. Wiley Online Library; 2019;21:e13163.

Garcia-Hermoso D, Criscuolo A, Lee SC, Legrand M, Chaouat M, Denis B, et al. Outbreak of invasive wound mucormycosis in a burn unit due to multiple strains of Mucor circinelloides f. circinelloides resolved by whole-genome sequencing. MBio. Am Soc Microbiol; 2018;9:e00573–18.

Goswami RS, Kistler HC. Heading for disaster: Fusarium graminearum on cereal crops. Mol Plant Pathol. 2004;5:515–25.

Nelson PE, Dignani MC, Anaissie EJ. Taxonomy, biology, and clinical aspects of Fusarium species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:479–504.

Correll DP, Luzi SA, Nelson BL. Allergic fungal sinusitis. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:488–91.

Kurien M, Anandi V, Raman R, Brahmadathan KN. Maxillary sinus fusariosis in immunocompetent hosts. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106:733–6.

Al-Hatmi AMS, Bonifaz A, Ranque S, Sybren de Hoog G, Verweij PE, Meis JF. Current antifungal treatment of fusariosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;51:326–32.

Homa M, Galgóczy L, Manikandan P, Narendran V, Sinka R, Csernetics Á, et al. South Indian Isolates of the Fusarium solani species complex from clinical and environmental samples: Identification, antifungal susceptibilities, and virulence. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1052.

Sharma S, Das S, Virdi A, Fernandes M, Sahu SK, Koday NK, et al. Re-appraisal of topical 1% voriconazole and 5% natamycin in the treatment of fungal keratitis in a randomised trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:1190–5.

Price CL, Parker JE, Warrilow AG, Kelly DE, Kelly SL. Azole fungicides - understanding resistance mechanisms in agricultural fungal pathogens. Pest Manag Sci. 2015;71:1054–8.

Dalhoff A. Does the use of antifungal agents in agriculture and food foster polyene resistance development? A reason for concern. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;13:40–8.

Zupančič J, Novak Babič M, Zalar P, Gunde-Cimerman N. The black yeast Exophiala dermatitidis and other selected opportunistic human fungal pathogens spread from dishwashers to kitchens. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148166.

Hiruma M, Kawada A, Ohata H, Ohnishi Y, Takahashi H, Yamazaki M, et al. Systemic phaeohyphomycosis caused by Exophiala dermatitidis Systemische Phäohyphomykose verursacht durch Exophiala dermatitidis. Mycoses. 1993;36:1–7.

Ajanee N, Alam M, Holmberg K, Khan J. Brain abscess caused by Wangiella dermatitidis: Case report. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:197–8.

Ozawa Y, Suda T, Kaida Y, Kato M, Hasegaw H, Fujii M, et al. A case of bronchial infection of Wangiella dermatitidis. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi= J Japanese Respir Soc. 2007;45:907–11.

Alabaz D, Kibar F, Arikan S, Sancak B, Celik U, Aksaray N, et al. Systemic phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala (Wangiella) in an immunocompetent child. Med Mycol. 2009;47:653–7.

Chang X, Li R, Yu J, Bao X, Qin J. Phaeohyphomycosis of the central nervous system caused by Exophiala dermatitidis in a 3-year-old immunocompetent host. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:342–5.

Suzuki K, Nakamura A, Fujieda A, Nakase K, Katayama N. Pulmonary infection caused by Exophiala dermatitidis in a patient with multiple myeloma: A case report and a review of the literature. Med Mycol Case Rep Elsevier. 2012;1:95–8.

Griffard EA, Guajardo JR, Cooperstock MS, Scoville CL. Isolation of Exophiala dermatitidis from pigmented sputum in a cystic fibrosis patient. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45:508–10.

Kondori N, Lindblad A, Welinder-Olsson C, Wennerås C, Gilljam M. Development of IgG antibodies to Exophiala dermatitidis is associated with inflammatory responses in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13:391–9.

Silva WC, Gonçalves SS, Santos DWCL, Padovan ACB, Bizerra FC, Melo ASA. Species diversity, antifungal susceptibility and phenotypic and genotypic characterisation of Exophiala spp. infecting patients in different medical centres in Brazil. Mycoses. 2017;60:328–37.

Badali H, De Hoog GS, Sudhadham M, Meis JF. Microdilution in vitro antifungal susceptibility of Exophiala dermatitidis, a systemic opportunist. Med Mycol. 2011;49:819–24.

Malo ME, Schultzhaus Z, Frank C, Romsdahl J, Wang Z, Dadachova E. Transcriptomic and genomic changes associated with radioadaptation in Exophiala dermatitidis. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:196–205.

Song Y, Du M, Menezes da Silva N, Yang E, Vicente VA, Sybren de Hoog G, et al. Comparative Analysis of Clinical and Environmental Strains of Exophiala spinifera by Long-Reads Sequencing and RNAseq Reveal Adaptive Strategies. Front Microbiol Frontiers; 2020;11:1880.

Setianingrum F, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Denning DW. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: a review of pathobiology and clinical aspects. Med Mycol. 2019;57:133–50.

Rhodes J, Beale MA, Vanhove M, Jarvis JN, Kannambath S, Simpson JA, et al. A population genomics approach to assessing the genetic basis of within-host microevolution underlying recurrent cryptococcal meningitis infection. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2017;7:1165–76.

Billmyre RB, Clancey SA, Heitman J. Natural mismatch repair mutations mediate phenotypic diversity and drug resistance in Cryptococcus deuterogattii. Elife. eLife Sciences Publications Limited; 2017;6:e28802.

Stone NRH, Rhodes J, Fisher MC, Mfinanga S, Kivuyo S, Rugemalila J, et al. Dynamic ploidy changes drive fluconazole resistance in human cryptococcal meningitis. J Clin Invest. Am Soc Clin Investig; 2019;129:999–1014.

Farrer RA, Borman AM, Inkster T, Fisher MC, Johnson EM, Cuomo CA, Genomic epidemiology of a Cryptococcus neoformans case cluster in Glasgow, Scotland, . Microb Genomics. Microbiol Soc. 2018;2021:537.

Ma L, Chen Z, Kutty G, Ishihara M, Wang H, Abouelleil A, et al. Genome analysis of three Pneumocystis species reveals adaptation mechanisms to life exclusively in mammalian hosts. Nat Commun Nature Publishing Group. 2016;7:1–14.

Cissé OH, Hauser PM. Genomics and evolution of Pneumocystis species. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;65:308–20.

Nevez G, Magois E, Duwat H, Gouilleux V, Jounieaux V, Totet A. Apparent absence of Pneumocystis jirovecii in healthy subjects. Clin Infect Dis. The University of Chicago Press; 2006;42:e99–101.

Ponce CA, Gallo M, Bustamante R, Vargas SL. Pneumocystis colonization is highly prevalent in the autopsied lungs of the general population. Clin Infect Dis. The University of Chicago Press; 2010;50:347–53.

Gottlieb MS, Schanker HM, Fan PT, Saxon A, Weisman JD, Pozalski I. Pneumocystis pneumonia—Los Angeles. MMWR. 1981;30:250–2.

Thomas Jr CF, Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med. Mass Medical Soc; 2004;350:2487–98.

Leigh TR, Kangro HO, Gazzard BG, Jeffries DJ, Collins JV. DNA amplification by the polymerase chain reaction to detect sub-clinical Pneumocystis carinii colonization in HIV-positive and HIV-negative male homosexuals with and without respiratory symptoms. Respir Med. 1993;87:525–9.

Roux A, Canet E, Valade S, Gangneux-Robert F, Hamane S, Lafabrie A, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with or without AIDS, France. Emerg Infect Dis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014;20:1490.

Crothers K, Huang L, Goulet JL, Goetz MB, Brown ST, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, et al. HIV infection and risk for incident pulmonary diseases in the combination antiretroviral therapy era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. American Thoracic Society; 2011;183:388–95.

Nahimana A, Rabodonirina M, Bille J, Francioli P, Hauser PM. Mutations of Pneumocystis jirovecii dihydrofolate reductase associated with failure of prophylaxis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother Am Soc Microbiol. 2004;48:4301–5.

Cissé OH, Pagni M, Hauser PM. De novo assembly of the Pneumocystis jirovecii genome from a single bronchoalveolar lavage fluid specimen from a patient. MBio. Am Soc Microbiol; 2013;4.

Schmid-Siegert E, Richard S, Luraschi A, Mühlethaler K, Pagni M, Hauser PM. Mechanisms of surface antigenic variation in the human pathogenic fungus Pneumocystis jirovecii. MBio. 2017;8.

Cissé OH, Ma L, Khil PP, Dekker JP, Kutty G, Bishop L, et al. Comparative population genomics analysis of the mammalian fungal pathogen Pneumocystis. MBio. Am Soc Microbiol; 2018;9.

Hope WW, Walsh TJ, Denning DW. Laboratory diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:609–22.

Shah AA, Hazen KC. Diagnostic accuracy of histopathologic and cytopathologic examination of Aspergillus species. Am J Clin Pathol. Oxford University Press Oxford, UK; 2013;139:55–61.

Kozel TR, Wickes B. Fungal diagnostics. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2014;4:a019299.

Lass-Flörl C. Current challenges in the diagnosis of fungal infections. Hum Fungal Pathog Identif. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 3–15.

Ostrosky-Zeichner L. Invasive mycoses: diagnostic challenges. Am J Med. 2012;125:S14-24.

Arvanitis M, Anagnostou T, Fuchs BB, Caliendo AM, Mylonakis E. Molecular and nonmolecular diagnostic methods for invasive fungal infections. Clin Microbiol Rev Am Soc Microbiol. 2014;27:490–526.

Andes DR, Ghannoum MA, Mukherjee PK, Kovanda LL, Lu Q, Jones ME, et al. Outcomes by MIC values for patients treated with isavuconazole or voriconazole for invasive aspergillosis in the phase 3 seCURE and vital trials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63.

Miyazaki T, Kohno S, Mitsutake K, Maesaki S, Tanaka K, Ishikawa N, et al. Plasma (1–> 3)-beta-D-glucan and fungal antigenemia in patients with candidemia, aspergillosis, and cryptococcosis. J Clin Microbiol Am Soc Microbiol. 1995;33:3115–8.

Klont RR, Mennink-Kersten MASH, Verweij PE. Utility of Aspergillus antigen detection in specimens other than serum specimens. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1467–74.

Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Alexander BD, Kett DH, Vazquez J, Pappas PG, Saeki F, et al. Multicenter clinical evaluation of the (1→ 3) β-D-glucan assay as an aid to diagnosis of fungal infections in humans. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:654–9.

Martin-Souto L, Buldain I, Areitio M, Aparicio-Fernandez L, Antoran A, Bouchara J-P, et al. ELISA test for the serological detection of Scedosporium/Lomentospora in Cystic Fibrosis patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. Frontiers Media SA; 2020;10:602089.

Page ID, Baxter C, Hennequin C, Richardson MD, van Hoeyveld E, van Toorenenbergen AW, et al. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of four Aspergillus-specific IgG assays for the diagnosis of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;91:47–51.

Ramanan P, Wengenack NL, Theel ES. Laboratory diagnostics for fungal infections: a review of current and future diagnostic assays. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38:535–54.

Sewell TR, Zhu J, Rhodes J, Hagen F, Meis JF, Fisher MC, et al. Nonrandom distribution of azole resistance across the global population of Aspergillus fumigatus. MBio American Soc Microbiol. 2019;10:e00392-e419.

Morton CO, White PL, Barnes RA, Klingspor L, Cuenca-Estrella M, Lagrou K, et al. Determining the analytical specificity of PCR-based assays for the diagnosis of IA: What is Aspergillus? Med Mycol. 2017;55:402–13.

White PL, Posso RB, Barnes RA. Analytical and clinical evaluation of the pathonostics aspergenius assay for detection of invasive aspergillosis and resistance to azole antifungal drugs directly from plasma samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:2356–66.

Dannaoui E, Gabriel F, Gaboyard M, Lagardere G, Audebert L, Quesne G, et al. Molecular diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis and detection of azole resistance by a newly commercialized PCR kit. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:3210–8.

Egger M, Jenks JD, Hoenigl M, Prattes J. Blood Aspergillus PCR: the good, the bad, and the ugly. J Fungi. 2020;6:18.

Guegan H, Chevrier S, Belleguic C, Deneuville E, Robert-Gangneux F, Gangneux JP. Performance of molecular approaches for Aspergillus detection and azole resistance surveillance in cystic fibrosis. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:531.

Morris A, Norris KA. Colonization by Pneumocystis jirovecii and its role in disease. Clin Microbiol Rev Am Soc Microbiol. 2012;25:297–317.

Flori P, Bellete B, Durand F, Raberin H, Cazorla C, Hafid J, et al. Comparison between real-time PCR, conventional PCR and different staining techniques for diagnosing Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia from bronchoalveolar lavage specimens. J Med Microbiol Microbiol Soc. 2004;53:603–7.

Khodadadi H, Mirhendi H, Mohebali M, Kordbacheh P, Zarrinfar H, Makimura K. Pneumocystis jirovecii colonization in non-HIV-infected patients based on nested-PCR detection in bronchoalveolar lavage samples. Iran J Public Health. Tehran University of Medical Sciences; 2013;42:298–305.

Etoh K. Evaluation of a real-time PCR assay for the diagnosis of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Kurume Med J. Kurume University School of Medicine; 2009;55:55–62.

Fauchier T, Hasseine L, Gari-Toussaint M, Casanova V, Marty PM, Pomares C. Detection of Pneumocystis jirovecii by quantitative PCR to differentiate colonization and pneumonia in immunocompromised HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients. J Clin Microbiol Am Soc Microbiol. 2016;54:1487–95.

Badiee P, Arastefar A, Jafarian H. Comparison of histopathological analysis, culture and polymerase chain reaction assays to detect mucormycosis in biopsy and blood specimens. Iran J Microbiol. 2013;5:406–10.

Lackner M, Caramalho R, Lass-Flörl C. Laboratory diagnosis of mucormycosis: current status and future perspectives. Future Microbiol Future Med. 2014;9:683–95.

Millon L, Herbrecht R, Grenouillet F, Morio F, Alanio A, Letscher-Bru V, et al. Early diagnosis and monitoring of mucormycosis by detection of circulating DNA in serum: retrospective analysis of 44 cases collected through the French Surveillance Network of Invasive Fungal Infections (RESSIF). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:810-e1.

Millon L, Larosa F, Lepiller Q, Legrand F, Rocchi S, Daguindau E, et al. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction detection of circulating DNA in serum for early diagnosis of mucormycosis in immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:e95-101.

Muraosa Y, Schreiber AZ, Trabasso P, Matsuzawa T, Taguchi H, Moretti ML, et al. Development of cycling probe-based real-time PCR system to detect Fusarium species and Fusarium solani species complex (FSSC). Int J Med Microbiol. 2014;304:505–11.

Castelli MV, Buitrago MJ, Bernal-Martinez L, Gomez-Lopez A, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M. Development and validation of a quantitative PCR assay for diagnosis of scedosporiosis. J Clin Microbiol Am Soc Microbiol. 2008;46:3412–6.

Nagano Y, Elborn JS, Millar BC, Goldsmith CE, Rendall J, Moore JE. Development of a novel PCR assay for the identification of the black yeast, Exophiala (Wangiella) dermatitidis from adult patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). J Cyst Fibros. 2008;7:576–80.