Abstract

Powerful generative models, particularly in natural language modelling, are commonly trained by maximizing a variational lower bound on the data log likelihood. These models often suffer from poor use of their latent variable, with ad-hoc annealing factors used to encourage retention of information in the latent variable. We discuss an alternative and general approach to latent variable modelling, based on an objective that encourages a perfect reconstruction by tying a stochastic autoencoder with a variational autoencoder (VAE). This ensures by design that the latent variable captures information about the observations, whilst retaining the ability to generate well. Interestingly, although our model is fundamentally different to a VAE, the lower bound attained is identical to the standard VAE bound but with the addition of a simple pre-factor; thus, providing a formal interpretation of the commonly used, ad-hoc pre-factors in training VAEs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Generative latent variable models are probabilistic models of observed data x of the form \(p(x,z)=p(x|z)p(z)\), where z is the latent variable. These models are widespread in machine learning and statistics. They are useful both because of their ability to generate new data and because the posterior p(z|x) provides insight into the low dimensional representation z corresponding to the high dimensional observation x. These latent z values are then often used in downstream tasks, such as topic modelling (Dieng et al. 2017), multi-modal language modeling (Kiros et al. 2014), and image captioning (Mansimov et al. 2016; Pu et al. 2016).

Latent variable models, particularly in the form of Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) (Kingma and Welling 2014; Rezende et al. 2014), have been successfully employed in natural language modelling tasks using varied architectures for both the encoder and the decoder (Bowman et al. 2016; Dieng et al. 2017; Semeniuta et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2017; Shah et al. 2017). However, an architecture that is able to effectively capture meaningful semantic information into its latent variables is yet to be discovered.

A VAE approach to language modelling was given by Bowman et al. (2016), the graphical model for which is shown in Fig. 1a. This forms a generative model p(x|z)p(z) of sentence x, based on latent variable z.

Since the integral \(p(x) = \int p(x|z)p(z){d}z\) is typically intractable, a common approach is to maximize the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) on the log likelihood,

where \(\langle {\cdot }\rangle _{q(z|x)}\) is the expectation with respect to the variational distribution q(z|x), and \(D_{\mathrm {KL}}[\cdot ||\cdot ]\) represents the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence. Summing over all datapoints x gives a lower bound on the likelihood of the full dataset.

In language modelling, typically both the generative model (decoder) p(x|z), and variational distribution (encoder) q(z|x), are parameterised using an LSTM recurrent neural network—see for example Bowman et al. (2016). This autoregressive generative model is so powerful that the maximum ELBO is achieved without making appreciable use of the latent variable in the model. Indeed, if trained using the SGVB algorithm (Kingma and Welling 2014), the model learns to ignore the latent representation and effectively relies solely on the decoder to generate good sentences. This is evidenced by the KL term in the objective function converging to zero, indicating that the approximate posterior distribution of the latent variable is trivially converging to its prior distribution.

The dependency between what is represented by latent variables, and the capacity of the decoding distribution (i.e., its ability to model the data without using the latent) is a general phenomenon. Yang et al. (2017) used a lower capacity dilated CNN decoder to generate sentences, preventing the KL term going to zero. Gulrajani et al. (2017) and Higgins et al. (2017) have discussed this in the context of image processing. A clear explanation of this phenomenon in terms of Bit-Back Coding is given in Chen et al. (2017).

A mechanism to avoid the model ignoring the latent entirely, while allowing a high capacity decoder is discussed in Bowman et al. (2016) and uses an alternative training procedure called “KL annealing”—slowly turning on the KL term in the ELBO during training. KL annealing allows the model to use its latent variable to some degree by forcing the model into a local maximum of its objective function. Modifying the training procedure in this way to preferentially obtain local maxima suggests that the objective function used in Bowman et al. (2016) may not be ideal for modelling language in such a way as to create a model that leverages its latent variables.

2 High-fidelity latent variable modelling with AutoGen

We propose a new generative latent-variable model motivated by the autoencoder framework (Hinton and Zemel 1994; Hinton and Salakhutdinov 2006). Autoencoders are trained to reconstruct data through a low-dimensional bottleneck layer, and as a result, construct a dimensionally-reduced representation from which the data can be reconstructed. By encouraging reconstruction in our model, we force the latent variable to represent the input data, overcoming the issues faced by VAEs (Bowman et al. 2016) where the latent variable is ignored, as discussed in Sect. 1.

To autoencode in a probabilistic model, we start by considering a ‘stochastic autoencoder’ (SAE) in which we would need to maximize the likelihood of a reconstruction:

where \(x'\) represents the reconstruction and the training data is denoted by \(\{x_n\}\). Maximising this likelihood would encourage high-fidelity reconstruction from the stochastic embedding z by tying the input data x and the output \(x'\), much like an autoencoder. The associated graphical model is shown in Fig. 1b.

However, it is not immediately clear how to train such a model—constructing a lower bound on the likelihood using variational methods common in the VAE literature will give rise to an intractable p(x) term. This SAE would also not allow generation from a prior distribution, as in the case of VAEs. In order to leverage both prior generation and high-fidelity reconstruction from the latent variable, we propose to maximize the likelihood of a SAE and a VAE under a set of assumptions that tie the two models together:

The reconstruction term is given in Eq. 2, while we can write the generative term as

Crucially, maximizing \(\mathcal {L}_\mathrm{AutoGen}\) does not correspond to maximizing the log likelihood of the data as in the case of a VAE, nor would a lower bound on \(\mathcal {L}_\mathrm{AutoGen}\) correspond to the VAE ELBO (Eq. 1). Instead, we will see that \(\mathcal {L}_\mathrm{AutoGen}\) represents the log likelihood of a different model that combines both VAEs and SAEs.

As yet, we have not specified the relationship between the two terms in \(\mathcal {L}_\mathrm{AutoGen}\), Eqs. 2 and 4. Firstly, we assume that the generative model \(p_\text {VAE}(x=x_n |z)\) in the VAE is the same as the reconstruction model \(p_\text {SAE}(x'=x_n |z)\) in the SAE, and that the two models share a prior: \(p_\text {SAE}(z) = p_\text {VAE}(z)\). Under this equality assumption, it makes sense to denote these distributions identically as: \(p(x=x_n |z)\) and p(z), respectively. Secondly, we assume that the encoding and decoding distributions in the stochastic autoencoder are symmetric. Using Bayes’ rule, we write these assumptions as

These assumptions constrain the two otherwise-independent models, allowing AutoGen to demand both generation from the prior (like VAEs) and high-fidelity reconstructions from the latent (like autoencoders), all while specifying a single probability model, \(p(x=x_n|z)\).

Indeed, the equality assumption allows us to write \(p_\text {SAE}(x=x_n|z) = p(x=x_n|z)\) as well as \(p_\text {VAE}(x=x_n) = p(x=x_n)\). Thus, we can write Eq. 3 as:

Now applying Eq. 6 and combining the two logarithms, we find

In other words, AutoGen can be interpreted as the tying of two separate generations from the same model \(p(x=x_n|z)\). The graphical representation of this interpretation is shown in Fig. 1, where the dashed line corresponds to the tying (equality) of the two generations.

With the AutoGen assumptions, a simple lower bound for \(\mathcal {L}_\mathrm{AutoGen}\) can be derived following from Eq. 8 and the standard variational lower bound arguments:

2.1 Multiple reconstructions

We see that the variational lower bound derived for AutoGen in Eq. 9 is the same as that of the VAE (Kingma and Welling 2014; Rezende et al. 2014), but with a factor of 2 in the reconstruction term. It is important to emphasize, however, that the AutoGen objective is not a lower bound on the data log likelihood. Maximizing the lower bound in Eq. 9 represents a criterion for training a generative model p(x|z) that evenly balances both good spontaneous generation of the data \(p(x=x_n)\) as well as high-fidelity reconstruction \(p(x'=x_n|x=x_n)\), as it is a lower bound on the sum of those log likelihoods, Eq. 3.

Of course, AutoGen does not force the latent variable to encode information in a particular way (e.g. semantic representation in language models), but it is a necessary condition that the latent represents the data well in order to reconstruct it. We discuss the relation between AutoGen and other efforts to influence the latent representation of VAEs in Sect. 4.

A natural generalisation of the AutoGen objective and assumptions is to maximize the log likelihoods of m independent-but-tied reconstructions, instead of just 1. The arguments above then lead to a lower bound with a factor of \(1+m\) in front of the generative term:

Larger m encourages better reconstructions at the expense of poorer generation. We discuss the impact of the choice of m in Sect. 3.

3 Experiments

We train four separate language models, all with LSTM encoder and decoder networks as in Bowman et al. (2016). Two of these models are VAEs—one such variant uses KL annealing, and the other does not. We then train our baseline AutoGen model, which uses the objective in Eq. 9, and train an AutoGen variant using the objective in Eq. 10 with \(m=2\).

All of the models were trained using the BookCorpus dataset (Zhu et al. 2015), which contains sentences from a collection of 11,038 books. We restrict our data to contain only sentences with length between 5 and 30 words, and restrict our vocabulary to the most common 20,000 words. We use 90% of the data for training and 10% for testing. After preprocessing, this equates to 58.8 million training sentences and 6.5 million test sentences. All models in this section are trained using word drop as in Bowman et al. (2016).

Neither AutoGen models are trained using KL annealing. We consider KL annealing to be an unprincipled approach, as it destroys the relevant lower bound during training. In contrast, AutoGen provides an unfettered lower bound throughout training. Despite not using KL annealing, we show that AutoGen improves latent-variable descriptiveness compared to VAEs both with and without KL annealing for completeness.

3.1 Optimization results

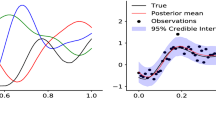

We train all models for 1 million iterations using mini-batches of 200 sentences. We use 500 hidden states for the LSTM cells in our encoder and decoder networks, and dimension 50 for our latent variable z. The objective functions differ between the four models, and so it is not meaningful to directly compare them. Instead, in Fig. 2 (left), we show the % of the objective function that is accounted for by the KL term. Despite the fact that AutoGen has a larger pre-factor in front of the \(\langle \log p(x|z) \rangle _{q(z|x)}\) term, the KL term becomes more and more significant with respect to the overall objective function for AutoGen with \(m=1\) and \(m=2\), as compared to the VAE. This suggests that the latent in AutoGen is putting less emphasis on matching the prior p(z), emphasizing instead the representation of the data.

(Left) \(-D_{\mathrm {KL}}[q(z|x_n)||p(z)]\) term as a % of overall objective for the four models throughout training. (Right) ELBO (log likelihood lower bound, Eq. 1) for the four models throughout training

To understand the impact of AutoGen on the log likelihood of the training data (which is the generation term in the AutoGen objective, Eq. 3), we compare the VAE ELBO in Eq. 1 of the four models during training. Since the ELBO is the objective function for the VAE, we expect it to be a relatively tight lower bound on the log likelihood. However, this only applies to the VAE. Indeed, if the VAE ELBO calculated with the AutoGen model is similar to that of the VAE, we can conclude that the AutoGen model is approximately concurrently maximizing the log likelihood as well as its reconstruction-specific objective.

In Fig. 2 (right) we show the ELBO for all four models. We see that, though the baseline AutoGen (\(m=1\)) ELBO is below that of the VAE, it tracks the VAE ELBO well and is non-decreasing. On the other hand, for the more aggressive AutoGen with \(m=2\), the ELBO starts decreasing early on in training and continues to do so as its objective function is maximized. Thus, for the baseline AutoGen with objective function corresponding to maximizing Eq. 3, we expect decent reconstructions without significantly compromising generation from the prior, whereas AutoGen (\(m=2\)) may have a much more degraded ability to generate well. In Sects. 3.2 and 3.3 we corroborate this expectation qualitatively by studying samples from the models.

3.2 Sentence reconstruction

Indications that AutoGen should more powerfully encode information into its latent variable were given theoretically in the construction of AutoGen in Sect. 2 as well as in Sect. 3.1 from the optimization results. To see what this means for explicit samples, we perform a study of the sentences reconstructed by the VAE as compared to those by AutoGen.

In Table 1, an input sentence x is taken from our test set, and a reconstruction is presented that maximizes p(x|z), as determined using beam search. We sample \(z\sim q(z|x)\) in this process, meaning we find different reconstructions every time from the same input sentence, despite the beam search procedure in the reconstruction.

AutoGen is qualitatively better at reconstructing sentences than the VAE. Indeed, even when the input sentence is not reconstructed verbatim, AutoGen is able to generate a coherent sentence with a similar meaning by using semantically similar words. For example in the last sentence, by replacing “some people” with “our parents”, and “never learn” with “never exist”. On the other hand, the VAE reconstructions regularly produce sentences that have little relation to the input. Note that without annealing, the VAE regularly ignores the latent, producing short, high-probability sentences reconstructed from the prior.

To make these results more quantitative, we ran three versions of a survey in which respondents were asked to judge the best reconstructions from two models. In the first survey, we received responses from 6 people who compared 120 pairs of reconstructions from the VAE and the VAE with annealing. The second survey received responses from 13 people over 260 sentences and compared reconstructions from the VAE with annealing to AutoGen (\(m=1\)). The third compared AutoGen (\(m=1\)) to AutoGen (\(m=2\)) and received 23 responses over 575 sentences. None of the respondents in these surveys were authors of this paper. The surveys were designed in this way to provide an easy binary question for the respondents. They provide a suitable test of the models due to the transitive nature of the comparisons.

Our survey results are shown in Table 2. We can clearly see that AutoGen with \(m=2\) outperforms AutoGen with \(m=1\), as expected. Similarly, AutoGen with \(m=1\) outperforms the VAE with annealing, and the VAE with annealing outperforms the VAE. All results have greater than 99% confidence.

3.3 Sentence generation

The objective function of AutoGen encourages the generation of higher-fidelity reconstructions from its approximate posterior. The fundamental trade-off is that it may be less capable of generating sentences from its prior.

To investigate the qualitative impact of this trade-off, we now generate samples from the prior \(z \sim \mathcal {N}(0,\text {I})\) of the VAE and AutoGen. For a given latent z, we generate sentences \(x'\) as in Sect. 3.2. Results are shown in Table 3, where we see that both models appear to generate similarly coherent sentences; there appears to be no obvious qualitative difference between the VAE and AutoGen.

To be more quantitative, we ran a survey of 23 people—none of which were the authors—considering 392 sentences generated from the priors of all four of the models under consideration. We applied the same sentence filters to these generated sentences as we did to those generated in Table 3. We then asked the respondents whether or not a given sentence “made sense”, maintaining the binary nature of the question, but allowing the respondent to interpret the meaning of a sentence “making sense”. To minimize systematic effects, each respondent saw a maximum of 20 questions, evenly distributed between the four models. All sentences in the surveys were randomly shuffled with the model information obfuscated.

The results of our survey are shown in Table 4. Since the VAE generates systematically shorter sentences than the training data, which are inherently more likely to be meaningful, we split our results into short and long sentences (with length \(\le 10\) and \(>10\) tokens, respectively). We conclude that the VAE with annealing is better at generating short sentences than AutoGen (\(m=1\)). However, both models achieve equal results on generation quality for longer sentences. We also see that AutoGen (\(m=2\)) generates significantly worse sentences than other models, as expected. All results that differ by more 1 percentage point in the table are statistically significant with confidence greater than \(99\%\).

3.4 Latent manifold structure

Finally, with high-fidelity reconstructions from the latent, one would expect to be able to witness the smoothness of the latent space well. This seems to be the case, as can be seen in Table 5, where we show the reconstructions of a linear interpolation between two encoded sentences for VAE with annealing and for AutoGen (\(m=1\)). The AutoGen interpolation seems to be qualitatively smoother: while neighbouring sentences are more similar, there are fewer instances of reconstructing the same sentences at subsequent interpolation steps.

The reconstructions from the VAE without annealing have little dependence on the latent, and AutoGen (\(m=2\)) struggles to generate from the prior. As a consequence, both of these models show highly non-smooth interpolations with little similarity between subsequent sentences. The results for these models have therefore been omitted.

We have provided only a single sample interpolation, and though it was not cherry picked, we do not attempt to make a statistically significant statement on the smoothness of the latent space. Given the theoretical construction of AutoGen, and the robust results shown in previous sections, we consider smoothness to be expected. The sample shown is consistent with our expectations, though we do not consider it a definite empirical result.

4 Discussion

We have seen that AutoGen successfully improves the fidelity of reconstructions from the latent variable as compared to VAEs. It does so in a principled way, by explicitly modelling both generation of the data and high-fidelity reconstruction. This is especially useful when the generative model is powerful, such as the autoregressive LSTM in Bowman et al. (2016).

Other work toward enabling latent variables in VAE models to learn meaningful representations has focused on managing the structure of the representation, such as ensuring disentanglement. A detailed discussion of disentanglement in the context of VAEs is given by Higgins et al. (2017) and its references. An example of disentangling representations in the context of image generation is Gulrajani et al. (2017), where the authors restrict the decoding model to describe only local information in the image (e.g., texture, shading), allowing their latents to describe global information (e.g., object geometry, overall color).

Demanding high-fidelity reconstructions from latent variables in a model (e.g., AutoGen) is in tension with demanding specific information to be stored in the latent variables (e.g., disentanglement). This can be seen very clearly by comparing our work to Higgins et al. (2017), where the authors introduce an ad-hoc factor of \(\beta \) in front of the KL-divergence term of the VAE objective function, the ELBO. They find that \(\beta > 1\) is required to improve the disentanglement of their latent representations.

Interestingly, \(\beta > 1\) corresponds analytically to \(-1<m<0\) in Eq. 10, since the overall normalization of the objective function does not impact the location of its extrema. That is, Eq. 10 is equivalent to the \(\beta \)-VAE objective function with \(\beta = (1+m)^{-1}\).

Since m in AutoGen represents the number of times a high-fidelity reconstruction is demanded (in addition to a single generation from the prior), \(\beta \)-VAE with \(\beta > 1\) is analytically equivalent to demanding a negative number of high-fidelity reconstructions. As an analytic function of m, with larger m corresponding to higher-fidelity reconstructions, negative m would correspond to a deprecation of the reconstruction quality. This is indeed what the authors in Higgins et al. (2017) find and discuss. They view \(\beta \)-VAE as a technique to trade off more disentangled representations at the cost of lower-fidelity reconstructions, in contrast to our view of AutoGen as a technique to trade off higher-fidelity reconstructions at the cost of slightly inferior generation from the prior.

In connecting to \(\beta \)-VAE, we have considered AutoGen with m as a real number. Practically, m could take positive real values, and can be seen as a hyperparameter that requires task-specific tuning. From our results, we expect \(m\approx 1\) to be a useful ballpark value, with smaller m improving generation from the prior, and larger m improving reconstruction fidelity. The advantage of tuning m as described is that it has a principled interpretation at integer values; namely that of demanding m exact reconstructions from the latent, as derived in Sect. 2.

In this light, KL annealing amounts to starting with \(m=\infty \) at the beginning, and smoothly reducing m down to 0 during training. Thus, it is equivalent to optimizing the AutoGen lower bound given in Eq. 10 with varying m during training. However, AutoGen should never require KL annealing.

Scaling of the ELBO is common in multimodal generation, where the reconstruction terms are typically of different orders of magnitude (Vedantam et al. 2018; Wu and Goodman 2018). AutoGen can be adapted to provide a bound on a meaningful objective function in multimodal generation with well-scaled terms, by requiring a larger number of reconstructions for one data modality than the other. Autogen thus has broader applications in generative modelling, which the authors leave to future work.

5 Conclusions

In this paper, we introduced AutoGen: a novel modelling approach to improve the descriptiveness of latent variables in generative models, by combining the log likelihood of m high-fidelity reconstructions via a stochastic autoencoder, with the log likelihood of a VAE. This approach is theoretically principled in that it retains a bound on a meaningful objective, and computationally amounts to a simple factor of \((1+m)\) in front of the reconstruction term in the standard ELBO. We find that the most natural version of AutoGen (with \(m=1\)) provides significantly better reconstructions than the VAE approach to language modelling, and only minimally deprecates generation from the prior.

References

Bowman, S. R., Vilnis, L., Vinyals, O., Dai, A., Jozefowicz, R., & Bengio, S. (2016) Generating sentences from a continuous space. In Conference on computational natural language learning.

Chen, X., Kingma, D. P., Salimans, T., Duan, Y., Dhariwal, P., Schulman, J., et al. (2017). Variational lossy autoencoder. In International conference on learning representations.

Dieng, A. B., Wang, C., Gao, J., & Paisley J. (2017). TopicRNN: A recurrent neural network with long-range semantic dependency. In International conference on learning representations.

Gulrajani, I., Kumar, K., Ahmed, F., Taiga, A. A., Visin, F., Vazquez, D., & Courville, A. (2017). PixelVAE: A latent variable model for natural images. In International conference on learning representations.

Higgins, I., Matthey, L., Pal, A., Burgess, C., Glorot, X., Botvinick, M., Mohamed, S., & Lerchner, A. (2017). beta-VAE: Learning basic visual concepts with a constrained variational framework. In International conference on learning representations.

Hinton, G. E., & Salakhutdinov, R. R. (2006). Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science, 313(5786), 504–507.

Hinton, G. E., & Zemel, R. S. (1994). Autoencoders, minimum description length and helmholtz free energy. In Advances in neural information processing systems.

Kingma, D. P., & Welling, M. (2014). Auto-encoding variational Bayes. In International conference on learning representations.

Kiros, R., Salakhutdinov, R., & Zemel, R. (2014). Multimodal neural language models. In International conference on machine learning.

Mansimov, E., Parisotto, E., Ba, J. L., & Salakhutdinov, R. (2016). Generating images from captions with attention. In International conference on learning representations.

Pu, Y., Gan, Z., Henao, R., Yuan, X., Li, C., Stevens, A., & Carin, L. (2016). Variational autoencoder for deep learning of images, labels and captions. In Advances in neural information processing systems.

Rezende, D. J., Mohamed, S., & Wierstra, D. (2014). Stochastic backpropagation and approximate inference in deep generative models. In International conference on machine learning.

Semeniuta, S., Severyn, A., & Barth, E. (2017). A hybrid convolutional variational autoencoder for text generation. In Conference on empirical methods in natural language processing.

Shah, H., Zheng, B., & Barber, D. (2017). Generating sentences using a dynamic canvas. In Association for the advancement of artificial intelligence.

Vedantam, R., Fischer, I., Huang, J., & Murphy, K. (2018). Generative models of visually grounded imagination. In International conference on learning representations.

Wu, M., & Goodman, N. (2018). Multimodal generative models for scalable weakly-supervised learning. Preprint arXiv:1802.05335.

Yang, Z., Hu, Z., Salakhutdinov, R., & Berg-Kirkpatrick, T. (2017). Improved variational autoencoders for text modeling using dilated convolutions. In International conference on machine learning.

Zhu, Y., Kiros, R., Zemel, R., Salakhutdinov, R., Urtasun, R., Torralba, A., & Fidler, S. (2015). Aligning books and movies: Towards story-like visual explanations by watching movies and reading books. In International conference on computer vision.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Alan Turing Institute under the EPSRC Grant EP/N510129/1 and by AWS Cloud Credits for Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Editors: Karsten Borgwardt, Po-Ling Loh, Evimaria Terzi and Antti Ukkonen.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mansbridge, A., Fierimonte, R., Feige, I. et al. Improving latent variable descriptiveness by modelling rather than ad-hoc factors. Mach Learn 108, 1601–1611 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-019-05830-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-019-05830-1