Abstract

Students with disability tend to report lower levels of school engagement. To date, research has focused on building students’ extrinsic motivation and self-regulation with limited consideration of the impact of instructional barriers. In this mixed-methods study, we investigated the effect of teachers’ participation in the Accessible Pedagogies™ Program of Learning on the classroom experiences and engagement of 56 Year 10 students with disabilities impacting language and information processing. When asked in interviews what their teacher did to help them pay attention and to understand, students described teachers’ increased use of practices that were the focus of the program. Self-report questionnaire data revealed a positive, statistically significant increase in cognitive engagement for students whose teachers participated in Accessible Pedagogies™. No increase was observed for a Comparison Group. Findings suggest that the reduction of extraneous language and cognitive load through teachers’ use of Accessible Pedagogies™ may have helped students deploy available mental effort to engage in learning, rather than expend that effort to overcome unnecessary instructional barriers. Future research will investigate the impact of Accessible Pedagogies™ with larger samples and a wider range of students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last forty years, the United Nations have sought to coordinate international action to promote inclusion, equality, and prosperity of all persons. This aim was first enacted through the Millennial Development Goals (2000–2015; United Nations, 2008) and now the Sustainable Development Goals (2015–2030; United Nations, 2015). While these goals have changed and expanded over time, disability was largely ignored until The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development was adopted in 2015 (Lee & Pérez Bello, 2022). Recognition of disability in the SDGs is due to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD, United Nations, 2006), a legally binding human rights instrument and guiding framework for any policy or practice that has the potential to impact people with disability (Graham et al., 2023). The influence of the CRPD is clearest in SDG4: Education, which now contains two of the seven references to disability in The 2030 Agenda (United Nations, 2015). These references appear in two of the 10 targets for Goal 4: Target 4.5, requiring nations to “ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disability”, and Target 4.5a, requiring nations to “build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive and provide safe, non-violent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all” (United Nations, 2015, p. 21). Use of the terms “access” and “inclusive and effective learning environments” within these targets correspond with those used in the CRPD, which proclaims the human right to an inclusive education through Article 24: Education (Graham et al., 2023). However, these terms carry specific meaning and, for States Parties to achieve compliance, enactment of the SDG4 targets will need to take account of the guidance that has since been provided by the CRPD Committee.

In 2016, the CRPD Committee published General Comment No. 4 (GC4; United Nations, 2016), with the aim of guiding signatories to implement inclusive education in accordance with Article 24: Education. GC4 defines inclusive education as “a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers” (para 11). Later, in paragraph 22, the Committee emphasises that “[t]he entire education system must be accessible … [not simply] buildings, information and communications tools … [but also] the curriculum, educational materials, teaching methods, assessments and language and support services” (emphasis added, United Nations, 2016). GC4 has been described as a game-changer for it also distinguishes inclusive education from integration, which—despite Ainscow (1995) making a similar distinction some twenty years earlier—is the rock on which the implementation of inclusion has typically foundered (Graham, 2024). Integration is defined in GC4 as “a process of placing persons with disabilities in existing mainstream educational institutions, as long as the former can adjust to the standardised requirements of such institutions” (United Nations, 2016, para 11). In plain language, integration is the product of perceiving inclusion largely in terms of physical terms. However, it has long been observed that genuine inclusion requires more than physical presence in “mainstream” classrooms, although, as de Bruin (2024) notes, presence is a necessary precondition for genuine inclusion. For this reason, inclusive education has been described as both a place and a process (Graham, 2024). This process involves the elimination or minimisation of barriers through the provision of accommodations (known as reasonable adjustments in Australia) along with other necessary supports to ensure students with disability can access and participate in education on an equal basis. As adjustments are often retrospective and can be time-consuming to provide, better outcomes can often be achieved through universal design (Graham et al., 2018).

The concept of universal design originated in the field of architecture with the aim of designing spaces that can be used safely and independently by as many people as possible without the need for, or expense of, retrofitting (Graham et al., 2024). These ideas have gradually made their way into the field of education through broader reform to building codes which are increasingly requiring school designers to account for all learners through the provision of lifts, ramps, wider doorways, sound acoustics, break out rooms, and assistive technologies (Willis et al., 2024). However, barriers can be present in both physical and pedagogical learning environments with each having potential to impact the other (e.g. French et al., 2020). Research on physical learning environments, for example, has shown that ambient and extraneous noise can negatively impact teachers’ speech transmission and vocal health, as well as students’ access to instructional dialogue, impacting their comprehension and engagement (Connolly et al., 2019; Mealings et al., 2015). Importantly, not all students are the same and even those sharing the same learning environment can experience differential impacts on engagement and learning (Martin et al., 2015).

Engagement and learning

Student engagement is increasingly named in school improvement agendas, due to evidence of a positive relationship with academic achievement (Chi et al., 2018). While there are different models of engagement and a range of dimensions have been proposed (cf. Filsecker & Kerres, 2014; Nguyen et al., 2018; Reeve, 2013), there is general agreement that engagement is multi-dimensional. The most well-known and commonly used model was developed by Fredricks et al. (2004) who classified 44 empirical studies to propose three separate but interrelated dimensions: affective, behavioural, and cognitive. Affective engagement refers to students’ positive and/or negative feelings about academics, learning tasks, subjects, teachers and peers, and students’ sense of belonging (Fredricks, 2011; Fredricks et al., 2004). Behavioural engagement refers to school attendance, participation in homework and extra-curricular activities, adherence to classroom rules, and the effort students exert to sit, attend, and contribute to classroom tasks (Chi et al., 2018; Fredricks et al., 2004). Cognitive engagement refers to students’ self-regulated learning, use of deep learning strategies, retention of meaningful information, intellectual investment in the learning process (particularly when learning is difficult), and exertion of the effort necessary for comprehension and mastery of complex ideas (Fredricks, 2011; Fredricks et al., 2016). Fredricks’ model has been highly influential with most measures of engagement now incorporating affective, behavioural, and cognitive domains (Lam et al., 2014).

The malleable nature of student engagement and the promise it holds for achievement has prompted research into the quality of pedagogical learning environments and whether teaching quality affects engagement (Archambault et al., 2020). Findings have been mixed. For example, higher affective engagement has been associated with teachers’ provision of lesson structure, clear expectations, and consistent feedback (Kurdi et al., 2018; Wang & Eccles, 2013). Affective engagement has also been shown to increase with greater lesson structure and instructional support, but with higher effects for students from backgrounds of relative advantage compared to students from disadvantaged backgrounds (Nie & Lau, 2009). However, this may be related to differences in the conceptualisation and measurement of teaching quality. For example, Quin et al. (2017) surveyed 88 Year 7 students (male = 42, female = 46) and found that the quality of teaching contributed to students’ affective and behavioural engagement, but not cognitive engagement, a finding that the authors acknowledge deviates from prior research (e.g. Fredricks et al., 2005). However, while Quin et al. measured students’ emotional, behavioural, and cognitive engagement using the School Engagement Measure (Fredricks et al., 2005), they conceptualised teaching quality as “students’ perceptions of the degree to which their teachers supported their autonomy, competence, and relatedness”, which they measured with the Teacher as Social Context Questionnaire (TASC, Belmont et al., 1992). Their findings may have been affected by the sensitivity and focus of the TASC, which may not adequately target practices relevant to the cognitive dimensions of teaching and learning.

There have been changes over time in the conceptualisation and measurement of quality teaching. Although descriptions vary across various models and measures, there is now general agreement among researchers that there are three domains of quality: (1) supportive emotional climate, (2) classroom management, and (3) cognitive activation (Fauth et al., 2019). These three domains broadly correspond with Fredrick’s emotional, behavioural, and cognitive dimensions of engagement, and this may be why some studies find significant results for all three dimensions of engagement and others do not. Another reason may be differences in the conceptualisation of cognitive engagement with some researchers defining cognitive engagement in terms of beliefs and values about the importance of learning and others defining it as making an effort above and beyond the minimum required (Greene, 2015). Importantly, effort is relative and the minimum required for one student is not the same as another.

Barriers to engagement

Students with disability, particularly those with disabilities impacting language and information processing, such as Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Developmental Language Disorder (DLD), tend to report lower levels of engagement, including cognitive engagement (O’Donnell & Reschly, 2020). To improve cognitive engagement, O’Donnell and Reschly suggest a range of interventions to “promote a mastery goal orientation”, develop students’ self-regulation through “modelling, goal-setting, and self-monitoring”, and work with families “to deliver messages of motivational support” (p. 573). However, these interventions assume student impairment is the problem, ignoring the barriers that may be disabling them (Graham et al., 2024). Interventions that focus only on building the skills of students with disability will also leave those barriers in place, along with the additional effort they demand of these students and the frustrations they cause. It is in recognition of this problem that the CRPD Committee (United Nations, 2016, para 25) recommended that signatories adopt Universal Design for Learning (UDL), a comprehensive multidimensional framework that is aligned with the social model of disability and involves proactive removal of potential barriers to access and participation.

UDL draws on the principles of universal design to optimise how learners are engaged, how information is presented, and how learners can demonstrate their learning (CAST, 2018). UDL has three principles, each with three dimensions that unite to achieve a key goal. Within each are a series of checkpoints to guide practice within that specific area (Meyer et al., 2014). UDL is making headway in Australia but has not yet been widely adopted, leaving individual teachers to implement its principles in isolation, often in addition to an existing school-wide pedagogical framework (Graham & Tancredi, 2024). This, together with the complexity of the UDL framework with its multiple principles, dimensions, and a myriad of checkpoints and guidelines, can make implementation challenging (Zhang et al., 2024). While UDL is particularly valuable for inclusive lesson planning, the complexity of the framework renders it less useful for pedagogy, risking surface-level impact that does not shift the accessibility of classroom teaching.

Addressing pedagogical barriers

Accessible pedagogical learning environments are critical for students with “invisible” disabilities impacting language and information processing, such as those with ADHD and DLD. As these students tend not to receive adjustments, they are wholly reliant on the comprehensibility of classroom pedagogy (Graham & Tancredi, 2019). Long, complex instructions, abstraction, superfluous and/or tangential teacher talk, use of low-frequency words and developmentally inappropriate vocabulary, fast paced verbal instruction with infrequent pauses and/or lack of written and visual supports burden all students’ working memory and language comprehension systems. This burden is especially heavy for students with ADHD and DLD, who must expend significant cognitive effort to overcome these barriers in order to keep up, comprehend, and learn (Forsberg et al., 2021, Tancredi et al., 2023). This inequality in the effort that some students must expend to engage in learning and the possibility of its relationship to the accessibility of pedagogy is what we see missing from research that finds lower levels of cognitive engagement in these students and which seeks to improve engagement through student-focused interventions. From an inclusive education point of view, the question is not what strategies these students need to learn so that they can engage with complex ideas, but whether their ability to engage with complex ideas is impeded by instructional barriers and whether their engagement improves on removal of those barriers.

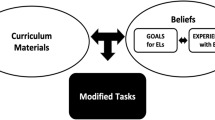

In 2022, a group of Australian secondary school English teachers (n = 21) participated in the Accessible Pedagogies™ Program of Learning (Graham & Tancredi, 2024), a 10-week pedagogical intervention designed to improve the accessibility of instructional practice by reducing barriers arising from extraneous language and cognitive load (Bussing et al., 2016; Gathercole & Alloway, 2004; Starling et al., 2012; Sweller et al., 2019). As shown in Table 1, Accessible Pedagogies™ has three domains and seven dimensions that correspond with a range of evidence-based strategies.

At the commencement of the program, each teacher consented to videorecording of two lessons, which were coded against the criteria outlined in the Accessible Pedagogies Observational Measure (APOM; Graham & Tancredi, 2024). The APOM has a 7-point scale and three ranges: low (1–2), mid (3–5), and high (6–7). At Time 1, most teachers scored in the low to low-midrange with only one scoring in the high range for all dimensions. Across the 10 weeks, participants were provided with individual feedback, completed self-directed online modules, and participated in interactive group online webinars. At the conclusion of the program, teachers were observed again for another two lessons.

Individual teacher Time 1 and Time 2 observation ratings were analysed using paired samples t-tests. Mean scores improved significantly for all seven Accessible Pedagogies™ dimensions with effect sizes (Cohen’s d) ranging from moderate (0.5–0.8) to high (0.8–1.1; Graham & Tancredi, 2024). While these improvements were not uniform across the 21 teachers, nor gains equal across dimensions, many participating teachers attested to a positive effect for their students with one initially resistant teacher joyfully reporting that her student “Michael” had engaged and passed Year 10 English for the first time (Graham & Tancredi, 2024). But, unless these practices positively enhance more than one student’s classroom experiences and engagement in learning, there may be little reason for systems, schools, and teachers to invest valuable time and emotional and intellectual energy into their implementation. In this paper, we examine questionnaire and interview data from students with language and/or attention difficulties whose teachers participated in the Accessible Pedagogies™ Program of Learning, and compare engagement outcomes of this group with a similar student group whose teachers did not participate to estimate the impact of measured improvements in the accessibility of teachers’ practice on students’ classroom experiences and engagement in learning.

Research design

The study on which this paper is based is part of the Accessible Assessment ARC Linkage project (LP180100830; Graham, Willis, et al., 2018), a large-scale mixed-methods waitlist study, involving an active Intervention Group participating in Accessible Pedagogies™ and a concurrent Comparison Group. This project was conducted in partnership with three state secondary schools in Queensland, Australia. The study was approved by the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Human Research Ethics Committee, and approval to conduct research was obtained from the Queensland Department of Education. The aim of the Accessible Assessment ARC Linkage project is to investigate whether improvements in the accessibility of summative assessment task sheets and teachers’ instructional practice improve student outcomes. Year 10 English was the focus because it is a compulsory subject throughout all 13 years of schooling in Australia and functions as a critical gateway to further opportunity (Tancredi et al., 2024).

This study focuses on the classroom experiences and engagement of a subgroup of 56 students with language and/or attentional difficulties before and after their English teachers participated in the Accessible Pedagogies™ Program of Learning. These students were recruited as part of a larger group and identified through parent completion of the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy Skills Student Language Scale (Nelson et al., 2016b) and the SNAP-IV (Swanson et al., 1982). Students underwent further assessment by a qualified speech pathologist using the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy Skills (Nelson et al., 2016a) and the Brown Executive Function and Attention Scales Student Form (Brown, 2019). Parents/carers were provided with a full report of the results which the research team used to investigate the barriers experienced by students with language and/or attention difficulties (see Tancredi et al., 2023). These insights were shared with teachers participating in the Program of Learning and, along with previous research with students with unspecified learning and behavioural difficulties (Graham et al., 2022), informed development of the student interview questions.

Of the 56 identified students, over two thirds (69.64%) had teachers who participated in the Program in Semester 1 or 2 of 2022 and these students comprise the two Intervention Groups (Table 2) in the present study. The remaining students had teachers who did not participate in the program, and these students comprise the Comparison Group. Importantly, students did not know their teachers were participating in the Program of Learning, nor did students know anything about the program. There were no pre-existing significant differences between the Intervention and Comparison Groups in age (Intervention M = 14.80 years, SD = 0.46; Comparison M = 14.67, SD = 0.49, p = 0.354) or gender (Intervention 49% male; Comparison 53% male, p = 0.810). Groups were also equivalent in a measure of reading comprehension (Intervention M = 60.70, SD = 10.05; Comparison M = 55.95, SD = 9.98, p = 0.192). In clinical assessments of language and attention skills (Tancredi et al., 2023), the largest impacts of impairment were observed for memory, effort, and vocabulary. Strategies to support students’ memory, attention, vocabulary, and information processing were therefore emphasised in the intervention with teachers.

Student interviews

All 56 students participated in two 25-min individual interviews probing attitudes to school, engagement, academic self-perception, perceptions of teaching, and classroom experiences. Interviews took place pre- and post-Intervention Group teachers’ participation in Accessible Pedagogies™. Some questions were presented visually to students using simple, large format text on an iPad. The iPad was used to give students the opportunity to respond directly by making selections for some questions (via multiple choice and using visual rating scales), to enhance accessibility, and to supplement the verbal interactions between interviewers and students (Tancredi & Graham, forthcoming). All interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. This paper focuses on students’ responses to three questions (Table 3) designed to tap the presence/absence of accessible teaching practices pre- and post-teachers’ participation in Accessible Pedagogies™ and their use of strategies to support attention and comprehension.

For interview question one (Table 3), students provided ratings of 16 teaching practices and responses were coded for analysis as: Rarely = 1, Sometimes = 2, Always = 3. The practice “Provides accessible slides” was presented to students as “Provides too much information on slides. Because this item required reverse scoring, it has been rephrased here. Our primary interest in designing and piloting these items was to examine their utility in capturing student perceptions of practices aligning with the APOM dimensions. Given the exploratory nature of these items, we report descriptive statistics only, calculating group means for each practice at Times 1 and 2 and representing these visually. Students’ responses to interview questions two and three (Table 3) at Time 2 were grouped by theme. Some students gave generic responses, like “helping everyone out” or “just, like, taught”, and these were coded under general support. Others spoke broadly about class being “more engaging” but without specific reason, for example: “Sometimes it's just like less worky and more like… fun. Like, it's work, but it's, like, not as worky” (Bella). The majority described their teachers’ use of specific strategies emphasised in Accessible Pedagogies™, and we focus on these statements here. All student names are pseudonyms.

Student Engagement in School Scale (SESS)

The Student Engagement in School Scale (SESS; Lam et al., 2014) measures student self-report of affective, behavioural, and cognitive engagement in the school context. Preliminary evidence shows the SESS to have acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.78), observed in a cross-cultural validation study of 3420 adolescents from 12 countries (Lam et al., 2014). The SESS has 33 items: nine focus on affective engagement (e.g. “I am happy to be at this school”), 12 on behavioural engagement (e.g. “When I’m in class, I participate in class activities”), and 12 on cognitive engagement (e.g. “I try to understand how the things I learn in school fit together with each other”; Lam et al., 2014, p. 231). Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree.

Analysis of the SESS used subscales derived through a re-analysis of the factor structure for the wider study sample, using exploratory factor analysis (Graham, Sweller et al., in preparation). This analysis resulted in six subscales, five of which are used in the present paper: Learning Engagement, Cognitive Engagement, School Liking, Persistence, and Hard Work. The sixth subscale, Extracurricular Participation, included items like “I am an active participant of school activities such as sport day and school picnic”. This subscale was not examined further, as items were not relevant to Australian students and not expected to be impacted by the intervention.

Change scores were created for the other five subscales to represent differences in student engagement before and after the intervention, with positive values indicating a gain in engagement, and negative values indicating a decrease. Only students who had undertaken the measure at both timepoints and at those proximal to the intervention were included in the analysis.Footnote 1 One-sample t-tests were used, separately for the Semester 2 Intervention Group (n = 10) and Comparison Group (n = 9), to see whether significant change occurred following the Semester 2 teachers’ participation in Accessible Pedagogies™. Independent groups t-tests were conducted on change scores to determine whether change in engagement differed between groups. Due to the small sample sizes for both groups, all analyses were replicated with their nonparametric equivalent, one-sample Wilcoxon signed rank tests and Mann–Whitney U tests.

Results

Does your year 10 English teacher…?

During interviews, students were presented with 16 practice descriptors on an iPad and asked to indicate whether their English teacher used each practice ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’. Figure 1 displays the order of students’ perceptions of their teachers’ frequency of use for each practice prior to (Time 1) and after (Time 2) their teachers’ participation in the Program of Learning. At a group level, students’ perception of change is mixed with minor improvements in some indicators, particularly for Catching and Maintaining Attention, Supporting Information Processing, and Vocabulary, along with no change in other indicators, and a decline in the provision of clear transition signals. These results reflect the variability in teachers’ adoption as described in the introduction to this paper and the emphasis we placed on memory, information processing, and vocabulary. Unlike trained observer ratings which averaged low to low-midrange at Time 1 and low to high-midrange at Time 2 (Graham & Tancredi, 2024), students’ ratings are positively skewed at both timepoints with most indicators sitting at the mid-point between ‘sometimes’ and ‘always’.

Average Ratings of Teacher Practice on the Accessibility of Pedagogy at Time 1 and 2. Note CLSI = Clarity of Language Structure and Expression, VOC = Vocabulary, CC = Comprehension Checking, CMA = Catching and Maintaining Attention, SIP = Supporting Information Processing, VS = Visual Supports, QCA = Quality, Clarity, and Alignment

What did your teacher do to help you pay attention?

When given the opportunity of a free verbal response, several students noted their teacher used regular check-ins to help them pay attention. For example, Tane reported “He keeps us on track… He doesn't let us slack off or anything”. Gabby said her teacher caught their attention using a verbal prompt prior to issuing further instruction: “He kind of just says it's important. No talking!” Seth pointed to his teacher’s use of a moderate instructional pace: “Uh, she usually, uh, she speaks with a certain tempo that uh, that I can actually pay attention, because if you speak too fast or too slow, I get a bit bored and distracted”. Arapeta reflected on a lesson where “there wasn't really much, like, ‘talking’”, suggesting reduced quantity of teacher talk helped him pay attention.

Students also identified that the use of visual supports and other resources supported their attention. Corben indicated value in “a lot of hand gestures… And, uh, PowerPoints”. For Shevlin, teachers’ use of multi-media supports like video helped “us to, kind of, watch and be engaged”. Other students reflected on their teachers’ use of the whiteboard. For example, Kiaan said “Yeah, she writes stuff on the board what we're gonna do”. Katie pointed to this same strategy, but extended her statement to make a clear connection to how this supported her attention and comprehension: “She writes like things on the board. So, like I can always look at that and know what she's saying”.

What did your teacher do to help you understand?

When asked what their teacher did to help them understand, some students said teachers had improved their use of explanation: “he explained it like, really… like, thoroughly” (Becky). Melissa said her teacher was clearer in her instructions and provided explicit steps to help her understand task criteria:

I think just, like, she really set it out, so we knew what we were doing. And just in a way dumbed it down, not that we're dumb but like, just made it, like if she had the criteria, she, like, usually that's not exactly the easiest thing to understand sometimes. She just really set it out and [was] going ‘This is all this means. Just do this’.

Sanjit said his teacher “spoke really clearly”, which helped him understand what to do in the lesson:

It's easy to listen when you know what you're doing. Just like when you get an explanation of what you're doing before [you start].

Danny reported his lessons were easier to understand because “all the terms were explained pretty well”. Flynn said that his teacher also “simplified certain terms”, supporting his comprehension. Manalia indicated her teacher was modelling and extending students’ vocabulary and noted this practice had changed of late:

Uh, she, um, informs us of, uh, certain words that The Outsider book author mentioned. And, uh, has discussion, uh, with our table groups about it. Well, she's been doing that for a bit, but it's a little bit different recently.

Katie reported her teacher regularly checked students’ comprehension though question and answer cycles: “She asks us if we do understand. And if we don't, she answers our questions that we have”. Similarly, Becky reported her teacher monitored and repaired signs of comprehension breakdown: “if you were still confused, he'd like, still come up to you”.

Ayyash said teachers’ use of pauses helped “space things out” which made things “easy to understand”. Corben also said an accessible instructional pace helped him understand and pointed to the importance of repetition: “Like, he speaks really, like, slowly so we can understand and, you know, repeats the important bits”. Emily reported her teacher chunked information and broke things down which “really… made it much more comprehendible.” Ananya said her teacher’s use of language that “isn't too difficult” helped her understand curriculum content: “So even if the content is hard, the language is easy so I can focus on the actual content, not what she's actually trying to say”. She also spoke positively about her teachers’ use of “PowerPoints with correlating slides to what she's saying. Um, it's all very easy to understand”. Arini said her teacher used “many resources. Um, like, handouts” and Emily said her teacher made the assessment task easier by providing “a step-booklet thing”.

Overall, students’ interview responses indicate positive reception of teachers’ use of key strategies emphasised in Accessible Pedagogies™. This was despite students not knowing their teacher participated in the program, nor the focus of the intervention. The critical question for us, however, is whether teachers’ adoption of strategies to reduce language and cognitive load made any impact on student engagement.

Student engagement

Change scores on the SESS subscales were examined to determine if there were any differences pre- and post-intervention in student engagement, separately for the Intervention and Comparison Groups. A significant increase in cognitive engagement was observed for students in the Semester 2 Intervention Group (see Table 4). Changes in other subscales were not significant for the Intervention Group. For the Comparison Group, there were no significant changes in engagement.

The one-sample Wilcoxon signed rank test results mirrored those of the t-tests above. Only cognitive engagement significantly improved, with the median post-intervention ranks significantly higher than 0, Mdn = 0.70, Z = 52, p = 0.013.

An independent samples t-test yielded a significantly greater degree of positive change in cognitive engagement for the Intervention Group compared to the Comparison Group, t(17) = 2.35, p = 0.031, 95% CI [0.07, 1.34], Hedge’s g = 1.03. No group differences were observed for any other subscales (ps > 0.05). Mann–Whitney U tests showed no significant differences between the Intervention and Comparison Groups on any subscales, with median post-intervention ranks for cognitive engagement in the Intervention Group non-significantly higher than for the Comparison Group, U = 21, p = 0.053. All other group differences were similarly non-significant (ps > 0.05).

Discussion

This study sought to investigate whether the removal of instructional barriers arising from extraneous language and cognitive load improved classroom experiences and engagement of Year 10 students with language and/or attentional difficulties. Analyses focused on students’ responses to three interview questions, and comparison of engagement outcomes for students whose teachers participated in the program of learning to students of non-participating teachers. During interview, students were asked to indicate their teachers’ frequency of use for 16 items aligned with strategies in the APOM. Overall, students’ ratings pre- and post-teachers’ participation revealed no change or only minor improvements. However, students’ responses to the two free verbal response questions highlighted strategies beyond the 16 items canvassed in question one, and these strategies strongly aligned with those emphasised in the intervention. For example, when asked what their teacher did to help them pay attention, students said teachers used regular check-ins, a key strategy emphasised with teachers for Catching and Maintaining Attention. Students also said teachers adjusted the pace, quantity, and complexity of verbal instruction, strategies we emphasised with teachers for Supporting Information Processing. Students referred to teachers’ increased use of videos, lists on the board, and scaffolded handouts, all strategies in the Visual Supports dimension.

When students reported what their English teacher did to help them understand, they said teachers spoke “really clearly” and used economical explanations, which are strategies for improving the Clarity of Language Structure and Expression. They also reported teachers both “simplified” complex terms and explicitly taught new words, key strategies we emphasised with teachers to support students’ Vocabulary. Students said teachers used intentional pauses during instruction, repeating “the important bits”, and using language that was “easy” so they could “focus on the actual content”, all practices we emphasised with teachers for Supporting Information Processing. Finally, students said teachers used “correlating slides to what she's saying”, a key practice in the Quality, Clarity, and Alignment dimension.

Correspondence between what students said teachers were doing to help them pay attention and understand in class, and the dimensions of Accessible Pedagogies™ are an important finding, especially given students did not know their teachers were participating in the intervention, nor what the program of learning entailed. Although exploratory, our findings suggest Accessible Pedagogies™ can support the creation of accessible pedagogical learning environments that are inclusive of students with disabilities impacting language and information processing, such as ADHD and DLD. Since this research was conducted, we have further refined the 16 practice descriptors to create a scale which teachers in participating schools have been voluntarily using with their students to gain feedback on the accessibility of their teaching in real time. In future research, we will use teacher and student feedback to refine the scale further and then test the utility of student report, coach report, and/or self-assessment—in combination with the APOM and independently—to determine which of these tools best help teachers enhance the accessibility of their classroom pedagogy.

A key question for this study was whether and how teachers’ participation in Accessible Pedagogies™ impacted student engagement, as this is typically lower for students with disability (O’Donnell & Reschly, 2020). Post-teachers’ participation, we observed a positive and statistically significant increase in cognitive engagement for students in the Intervention Group, with a large effect size. This finding was consistent across both parametric and nonparametric tests and, importantly, was not observed for students in the Comparison Group. There was also a significant difference between the Intervention and Comparison Groups in terms of the degree of change in cognitive engagement observed; however, as this finding was shown only on the independent t-test and not its nonparametric equivalent, it should be interpreted with caution. Notwithstanding, these findings provide support for the effectiveness of teachers’ adoption of Accessible Pedagogies™ in increasing cognitive engagement for participating students. While no other subscales showed significant gain for the Intervention Group, it is noteworthy that we observed a positive but non-significant gain in Persistence for students in the Intervention Group, unlike their peers in the Comparison Group. Given the small to medium effect size for this gain, it is possible that the lack of statistical significance reflects the small sample size.

While all students can experience the negative impacts of inaccessible teaching practices, students with disabilities that impact language and information processing like ADHD and DLD are most at risk. Our previous research found Accessible Pedagogies™ increased teachers use of evidence-based strategies to reduce extraneous language and cognitive load, with most teachers improving from low and low-midrange to mid- to high-midrange (Graham & Tancredi, 2024). The focus of the current study was to investigate whether those changes in teacher practice were noticed by students with language and/or attention difficulties and, given these students had earlier described the negative impact of instructional barriers (e.g. lack of explanation clarity, too much teacher talk, (Tancredi et al., 2023; Tancredi et al., 2024), whether the reduction of extraneous language and cognitive load through teachers’ adoption of Accessible Pedagogies™ made any difference to students’ classroom experiences and engagement. Despite the small sample size, we found a large effect for cognitive engagement, supporting our contention that it is easier to understand complex ideas and to intellectually invest in the learning process when teachers use pedagogies that support language and information processing; an observation made by some students when reflecting on the practices their teachers used to help them pay attention and understand. Our findings suggest reducing extraneous language and cognitive load in classroom pedagogy prevents the creation of instructional barriers that require even more mental effort from students with language and/or attention difficulties. In future research, our team will test the impact on engagement, learning, and behaviour with a larger sample and wider range of students.

Strengths, limitations, and future research

The mixed-methods study design afforded the opportunity for triangulation and the comparison of students whose teachers had and had not participated in Accessible Pedagogies™. While the sample size did constrain quantitative analyses, the observed increase in cognitive engagement was large in effect. Future research will focus on refining the specificity of the 16 items with larger groups and a broader range of students. This work will include refinements and additions to the items based on practices endorsed by students in their open responses. Future research will also investigate the optimal number of scale points for capturing variability in student perceptions of teacher practice, trialling the use of a 5- or 7-point scale. Finally, we will investigate these perceptions more proximally by administering this measure during or immediately following the relevant lesson.

Conclusion

Accessible pedagogical learning environments have the potential to contribute to the aims of SDG4 by supporting teachers to provide high-quality, inclusive, and equitable education. This research investigated the impact of teacher participation in Accessible Pedagogies™ on the classroom experiences and engagement of students with language and/or attentional difficulties. Although not knowing their teachers were participating in the Accessible Pedagogies™ Program of Learning or what that program entailed, students highlighted strategies emphasised in the program of learning and reported these as helping them pay attention and understand. Importantly, we found a large effect for cognitive engagement in students of participating teachers and no change for a Comparison Group whose teachers did not participate, suggesting the reduction of extraneous language and cognitive load enables students with disabilities like ADHD and DLD to spend precious capacity for mental effort on complex ideas, rather than expend that effort overcoming unnecessary instructional barriers.

Data availability

Data are not available to share openly, to protect the privacy and anonymity of study participants.

Notes

Students whose teachers participated in the Semester 1 Intervention Group did not complete the SESS immediately following the intervention, as their participation in that measure was used to assess a different component of the wider project. For this reason, these students (n = 26) were excluded from analysis of the SESS, to mitigate any possibility that factors unrelated to the intervention could impact upon engagement before assessment of outcomes took place.

References

Ainscow, M. (1995). Education for all: Making it happen [Keynote address]. International Special Education Congress.

Archambault, I., Pascal, S., Tardif-Grenier, K., Dupéré, V., Janosz, M., Parent, S., & Pagani, L. S. (2020). The contribution of teacher structure, involvement, and autonomy support on student engagement in low-income elementary schools. Teachers and Teaching, 26(5–6), 428–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1863208

Belmont, M., Skinner, E. A., Wellborn, J., & Connell, J. P. (1992). Teacher as social context (TASC): Two measures of teacher provision of involvement, structure, and autonomy support. Portland State University. https://www.pdx.edu/psychology/assessments

Brown, T. E. (2019). Brown executive function/attention scales. Pearson.

Bussing, R., Koro-Ljungberg, M., Gagnon, J. C., Mason, D. M., Ellison, A., Noguchi, K., Garvan, C. W., & Albarracin, D. (2016). Feasibility of school-based ADHD interventions: A mixed-methods study of perceptions of adolescents and adults. Journal of Attention Disorders, 20(5), 400–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713515747

CAST. (2018, August 31). UDL: The UDL Guidelines. https://udlguidelines.cast.org

Chi, M. T., Adams, J., Bogusch, E. B., Bruchok, C., Kang, S., Lancaster, M., Levy, R., Li, N., McEldoon, K. L., Stump, G. S., Wylie, R., Xu, D., & Yaghmourian, D. L. (2018). Translating the ICAP theory of cognitive engagement into practice. Cognitive Science, 42(6), 1777–1832. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12626

Connolly, D., Dockrell, J., Shield, B., Conetta, R., Mydlarz, C., & Cox, T. (2019). The effects of classroom noise on the reading comprehension of adolescents. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 145(1), 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.5087126

de Bruin, K. (2024). Inclusive education: A review of the evidence. In L. J. Graham (Ed.), Inclusive education for the 21st century: Theory, policy, and practice (2nd ed., pp. 95–114). Routledge.

Fauth, B., Decristan, J., Decker, A. T., Büttner, G., Hardy, I., Klieme, E., & Kunter, M. (2019). The effects of teacher competence on student outcomes in elementary science education: The mediating role of teaching quality. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102882

Filsecker, M., & Kerres, M. (2014). Engagement as a volitional construct: A framework for evidence-based research on educational games. Simulation & Gaming, 45(4–5), 450–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878114553569

Forsberg, A., Adams, E. J., & Cowan, N. (2021). The role of working memory in long-term learning: Implications for childhood development. In K. D. Federmeier (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (pp. 1–45). Elsevier.

Fredricks, J. A. (2011). Engagement in school and out-of-school contexts: A multidimensional view of engagement. Theory into Practice, 50(4), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2011.607401

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P., Friedel, J., & Paris, A. (2005). School engagement. In K. A. Moore & L. A. Lippman (Eds.), What do children need to flourish? (pp. 305–321). Springer.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Fredricks, J. A., Filsecker, M., & Lawson, M. A. (2016). Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learning and Instruction, 43, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.002

French, R., Imms, W., & Mahat, M. (2020). Case studies on the transition from traditional classrooms to innovative learning environments: Emerging strategies for success. Improving Schools, 23(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480219894408

Gathercole, S. E., & Alloway, T. P. (2004). Working memory and classroom learning. Dyslexia Review, 15, 4–9.

Graham, L. J. (2024). What is inclusion… and what is it not? In L. J. Graham (Ed.), Inclusive education for the 21st century: Theory, policy, and practice (2nd ed., pp. 18–37). Routledge.

Graham, L. J., Medhurst, M., Malaquias, C., Tancredi, H., de Bruin, C., Gillett-Swan, J., Poed, S., Spandagou, I., Carrington, S., & Cologon, K. (2023). Beyond Salamanca: A citation analysis of the CRPD/GC4 relative to the Salamanca Statement in inclusive and special education research. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 27(2), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1831627

Graham, L. J., Medhurst, M., Tancredi, H., Spandagou, I., & Walton, E. (2024). Fundamental concepts of inclusive education. In L. J. Graham (Ed.), Inclusive education for the 21st century: Theory, policy, and practice (2nd ed, pp. 60–80). Routledge.

Graham, L. J., Sweller, N., & Killingly, C. (in preparation). Does enhancing teacher capability in inclusive practice improve student engagement over and above accessible task design? [Manuscript in preparation]. Centre for Inclusive Education, Queensland University of Technology (QUT).

Graham, L. J., & Tancredi, H. (2019). In search of a middle ground: The dangers and affordances of diagnosis in relation to Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Developmental Language Disorder. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 24(3), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2019.1609248

Graham, L. J., & Tancredi, H. (2024). Accessible Pedagogies™. In L. J. Graham (Ed.), Inclusive education for the 21st century: Theory, policy and practice (2nd ed., pp. 198–222.). Routledge.

Graham, L. J., Tancredi, H., & Gillett-Swan, J. (2022). What makes an excellent teacher? Insights from junior high school students with a history of disruptive behavior. Frontiers in Education, 7, 883443. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.883443

Graham, L. J., Tancredi, H., Willis, J., & McGraw, K. (2018). Designing out barriers to student access and participation in secondary school assessment. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45, 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0266-y

Graham, L. J., Willis, J., Sweller, N., White, S., Gibson, A., de Luca, C., Dixon, G. (2018). Linkage Australian Research Council Linkage Projects Proposal LP180100830. Unpublished.

Greene, B. A. (2015). Measuring cognitive engagement with self-report scales: Reflections from over 20 years of research. Educational Psychologist, 50(1), 14–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.989230

Kurdi, V., Archambault, I., Brière-Nault, F., & Turgeon, L. (2018). Need-supportive teaching practices and student-perceived need fulfillment in low socioeconomic status elementary schools: The moderating effect of anxiety and academic achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 65, 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.06.002

Lam, S. F., Jimerson, S., Wong, B. P., Kikas, E., Shin, H., Veiga, F. H., Hatzichristou, C., Polychroni, F., Cefai, C., Negovan, V., Stanculescu, E., Yang, H., Liu, Y., Basnett, J., Duck, R., Farrell, P., Nelson, B., & Zollneritsch, J. (2014). Understanding and measuring student engagement in school: The results of an international study from 12 countries. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(2), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq000005710.1037/spq0000057

Lee, V., & Pérez Bello, J. I. (2022). Bridging the gap: Harnessing the synergies between the CRPD and the SDG monitoring frameworks. Handbook of disability: Critical thought and social change in a globalizing world (pp. 1–20). Springer Nature.

Martin, A. J., Papworth, B., Ginns, P., Malmberg, L. E., Collie, R. J., & Calvo, R. A. (2015). Real-time motivation and engagement during a month at school: Every moment of every day for every student matters. Learning and Individual Differences, 38, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.01.014

Mealings, K. T., Buchholz, J. M., Demuth, K., & Dillon, H. (2015). Investigating the acoustics of a sample of open plan and enclosed Kindergarten classrooms in Australia. Applied Acoustics, 100, 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2015.07.009

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. T. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional.

Nie, Y., & Lau, S. (2009). Complementary roles of care and behavioral control in classroom management: The self-determination theory perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34(3), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2009.03.001

Nelson, N. W., Plante, E., Helm-Estabrooks, N., & Hotz, G. (2016a). The test of integrated language and literacy skills. Brookes Publishing.

Nelson, N. W., Howes, B., & Anderson, M. A. (2016b). The test of integrated language and literacy skills: Student language scale. Brookes Publishing.

Nguyen, T. D., Cannata, M., & Miller, J. (2018). Understanding student behavioral engagement: Importance of student interaction with peers and teachers. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2016.1220359

O’Donnell, K. C., & Reschly, A. L. (2020). Student engagement and learning: Attention, behavioral, and emotional difficulties in School. In A. J. Martin, R. A. Sperling, & K. J. Newton (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology and students with special needs (pp. 557–583). Routledge.

Quin, D., Hemphill, S. A., & Heerde, J. A. (2017). Associations between teaching quality and secondary students’ behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement in school. Social Psychology of Education, 20, 807–829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9401-2

Reeve, J. (2013). How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 579–595. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032690

Starling, J., Munro, N., Togher, L., & Arciuli, J. (2012). Training secondary school teachers in instructional language modification techniques to support adolescents with language impairment: A randomized control trial. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 43(4), 474–495. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2012/11-0066)

Swanson, J. M., Nolan, W., & Pelham, W. E. (1982). The SNAP-IV rating scale. Resources in Education.

Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J. J., & Paas, F. (2019). Cognitive architecture and instructional design: 20 years later. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 261–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09465-5

Tancredi, H., & Graham, L. J. (forthcoming). Effective inclusive practices: What students with disability wish teachers knew about them and how they learn. In J. Specht, S. Sider, & K. Maich (Eds.), A research agenda for inclusive education. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Tancredi, H., Graham, L. J., & Killingly, C. (2024). Improving the accessibility of subject english for students with language and/or attention difficulties. The Australian Educational Researcher. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-024-00728-x

Tancredi, H., Graham, L. J., Killingly, C., & Sweller, N. (2023). Investigating the impact of impairment and barriers experienced by students with language and/or attentional difficulties. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 28(2), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2023.2285270

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

United Nations. (2008). Commitments for Achieving the Millennium Development Goals. https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2008highlevel/commitments.shtml

United Nations. (2015). Sustainable Development Goals: 17 goals to transform our world. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2016). Article 24: Right to inclusive education, CRPD/C/GC/4. United Nations.

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2013). School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: A longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learning and Instruction, 28, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.04.002

Willis, J., Gillett-Swan, J., Franz, J., Farahnak Majd, N., Carroli, L., Gallagher, J., & Bray, E. (2024). Thriving in vertical schools: Aspirations for inclusion and capability from a salutogenic design perspective. Learning Environments Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-024-09502-3

Zhang, L., Carter, R. A., Jr., Greene, J. A., & Bernacki, M. L. (2024). Unraveling challenges with the implementation of universal design for learning: A systematic literature review. Educational Psychology Review, 36(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09860-7

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council’s Linkage Projects funding scheme (LP180100830). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Australian Government or Australian Research Council. Haley Tancredi is a doctoral candidate from QUT’s Centre for Inclusive Education and recipient of a QUT Postgraduate Research Award scholarship. We would like to thank the students who participated in this study for giving generously their time, insights, and perspectives. We thank the reviewers of this article who gave their time and expertise to review the manuscript, providing helpful suggestions and supporting the authors to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research was partially supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council’s Linkage Projects funding scheme (LP180100830). Haley Tancredi is a doctoral candidate from QUT’s Centre for Inclusive Education and recipient of a QUT Postgraduate Research Award scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Haley Tancredi, Linda J. Graham, Callula Killingly, and Naomi Sweller. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests, financial, or non-financial interests to declare.

Ethical approval

All procedures in this research were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the associated institutional and national research committees. The study was approved by the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) human research ethics committee, and approval to conduct research was obtained from the Queensland Department of Education.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tancredi, H., Graham, L.J., Killingly, C. et al. Investigating the impact of Accessible Pedagogies on the experiences and engagement of students with language and/or attentional difficulties. Learning Environ Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-024-09514-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-024-09514-z