Abstract

Differential thermal analysis, thermogravimetry and evolved gas analysis, as well as the X-ray diffraction, were used to identify and to quantify the products of dicalcium silicate hydration. The samples were 38 years stored in laboratory conditions. The calcium hydroxide, calcium carbonate and calcium silicate hydrate contents were determined and discussed in terms of the specific properties of initial anhydrous phases used.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Portland cement is the primary component of modern concrete, and its use in the construction continues to increase [1, 2]. Despite decades of research, many questions regarding the hydration and long-term performance of cement-based materials remain unclear. One of the key issues that remain to be resolved is the atomic-, nano- and microscale structures of hydration products, particularly calcium silicate hydrates (C–S–H). Answers to these questions are critical to improve modern concrete science and technology to create durable, smart materials. Most research in cement hydration is limited to a three-year window of time. A structural and compositional characterization of cement pastes maturing for a long term is still lacked even though the typical design service life cycle of cementing material is, on average, 50 years and sometimes as long as 100 years. Therefore, it is important to recognize the changes occurring in the phase composition and microstructure of hardened cements over periods beyond 3 years and how the nature of the main binding phases is altered. The analysis of evolution of cementing material phase composition and microstructure at very late age is critical to determine its macroperformance.

There are some reports related to the studies of cement, alite or cement with supplementary cementing materials hydration products after longer periods of time (usually collected during repairing works, demolition, etc.) [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]; however, there are no data relating to the “second” cement constituent, viz. β-dicalcium silicate (belite—β-Ca2[SiO4]) hydration products.

The phase assemblage of Portland cement clinker is as follows (the abbreviations used in cement chemistry, where C=CaO; S=SiO2; A=Al2O3; F=Fe2O3 and H=H2O are used):

C3S (3CaO · SiO2) 50–70% (alite)

β-C2S (β 2CaO · SiO2) 15–30% (belite, larnite)

C3A (3CaO · Al2O3) 5–15% (calcium aluminate)

C4AF (4CaO · Al2O3 · Fe2O3) 5–15% (brownmillerite)

C3S + C2S > 70%

These phases: alite, belite, aluminate and brownmillerite are formed as solid solutions [1].

The hydration of the main calcium silicate cement constituents can be written briefly and schematically according to the following equations:

The sequence of the calcium disilicate (C2S) polymorphic transitions is as follows:

α-C2S | Hexagonal | > 1425 °C | |

α′H-C2S | Rhombohedral | 1160–1425 °C | |

α′L-C2S | Rhombohedral | 1160–680 °C | |

β-C2S | Monoclinic | Formed below 680 °C, unstable, must be stabilized | The only one having fairly good hydraulic properties |

γ-C2S | Rhombohedral | < 500 °C | The only one stable at room temperature in pure form |

β-C2S stabilization

-

By an addition of foreign ions—stabilizers, e.g., B3+, P5+, V5+, As5+, Cr6+ or the others,

-

By long-term synthesis at low temperature hindering the β → γ-C2S transformation,

-

By repeated heating and cooling of C2S powders; the effect depends upon the temperature,

-

By rapid quenching.

The stabilization of β-C2S in any Portland cement clinker results from the presence of many different stabilizing agents and relatively rapid cooling. The synthesis, structure, stabilization process and the transformations between the polymorphic forms have been widely reported, with special attention on the role of low temperature [10,11,12,13,14,15]. The hydration process of different belite materials was also studied, and many efforts were devoted to modify its hydraulic activity [16,17,18]. There is a common opinion that the belite phase synthesized/heated at low temperature quickly reacts with water because of the presence of very fine grains, disordered structure and very high specific surface.

In Portland cement, belite is a constituent having lower sintering temperature as compared to the tricalcium silicate—alite (at least 1450 °C). Because it is imperative to develop low-energy alternative binders considering the large amounts of energy consumed as well as carbon dioxide emissions involved in the manufacturing of ordinary Portland cement, the belite-rich cements hold promise for reduced energy consumption and CO2 emissions. However, their use is hindered by the slow hydration rates of ordinary belites [1, 16,17,18]. A contribution on rapid hardening behavior of β-C2S by accelerated carbonation curing appeared recently [19] among the other valuable reports relating to the use of thermal methods in the studies of cement hydration and the role of several factors in this process [20, 21]. For this reason, the comparative studies of different belite materials activity are needed.

Experimental

The samples being investigated here are 38-year-old dicalcium silicate (C2S) pastes prepared in 1980 and stored in laboratory conditions.

Materials and methods

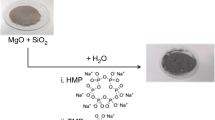

The specimens of dicalcium silicate were synthesized using reagent-grade calcium carbonate and silica mixtures with CaO/SiOs molecular ratio of 2.0. The mixtures were calcined at 1000 °C for 1 h; after calcination, they were pressed into pellets and sintered for 8 h at 800, 1000 and 1200 °C, respectively. One sample was doped with 1% Na2CrO4 and sintered at 1500 °C (temperature of clinker burning). One sample was sintered at 1500 °C, cooled to ambient temperature and heated without pelletizing to 800 °C to produce the γ polymorph. One should remember that the samples synthesized at low temperature (no 1–4 according to Table 1) need no stabilizers to produce the β-polymorph (see above). The list of samples is given in Table 1. The effects of synthesis of particular samples were verified by XRD. The presence of β-Ca2[SiO4] polymorph of disordered, fine-grained structure was found as one could expect basing on some reports. Finally, the samples were ground to the specific surface of ca. 3000 cm2 g−1, processed with water (w/s = 0.5) and sealed in glass tubes. After 38-year storage, the hydrated samples were very hard; however, they were crushed, ground with acetone and dried to produce the specimens for XRD and DTA/TG analysis. XRD data were collected by the Philips PW 1050/70 diffractometer device with Cu Kα radiation generated at 35 kV and 16 mA. The XRD data were collected in the 2θ range from 5° to 65° with a step of 0.05°. Thermoanalytical, thermogravimetric and the gas evolved data were obtained as a function of temperature by a simultaneous thermal analyzer STA 449F3 Jupiter (Netzsch) equipped with the quadrupole mass spectrometer QMS 403C Aëolos (Netzsch). Around 40 mg of sample powder was placed into the corundum crucible. Samples were heated in the synthetic air atmosphere, at the flow rate 40 mL min−1, at the heating rate 15 K min−1 from 40 to 1000 °C. The results of gas evolved analysis (EGA) are plotted as QMID (quasi-multi-ion detection) ion current curves versus temperature for gaseous (volatile) products—water vapor and carbon dioxide.

Results and discussion

The results are shown in Figs. 1–6 and in Tables 2–4.

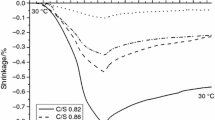

The following crystal constituents of hardened pastes were detected: calcium hydroxide (portlandite P), calcium carbonate—calcite (C) and/or vaterite (V) and calcium silicocarbonate—tilleyite (T). The initial material, presumably completely hydrated, was not visible. A broad “shoulder” from 28° to 33° (corresponding spacing from 2.7 to 3.1 Å) can be assigned to the poorly ordered C–S–H [2]. Due to the lack of crystallinity, the C–S–H phase exhibits no sharp peaks on the plots. Portlandite is present in all the samples. Relatively higher amount of calcium carbonate—vaterite—is found in the high temperature, stabilized by Cr additive, belite paste and in the low-temperature (800) belite paste, occurring together with calcite. It seems that in spite of the paste sealing in glass tubes there was the carbon dioxide diffusion through the glass walls and the products were subjected to the carbonation process. The set of TG curves is shown in Fig. 2. As shown in Figs. 2–6, the DTA, DTG and EGA curves give the clearest notation of changes occurring during heating. In the case of all samples, the three stages of thermal decomposition can be distinguished. In the temperature range up to ca. 250 °C, the dehydration of calcium silicate hydrates, so-called C–S–H phase, being the main hydration product, takes place. The continuous heating brings about some continuous weak mass loss, accompanied by water vapor release until the temperature range 400–500 °C, in which the rapid mass loss attributed to the crystalline calcium hydroxide—portlandite—decomposition occurs. However, as it can be derived from the DTG curves (Figs. 3–7), the two-step calcium hydroxide decomposition can be noticed in case of calcium silicates synthesized at lower temperatures. This seems to indicate the presence of less ordered (amorphous) precursor of portlandite occurring together with dominating portlandite [22]. Further heating leads to the decarbonation of pastes with the two steps, as it is illustrated on DTG and EGA curves (Figs. 3–7). The first one, attributed to the decomposition of vaterite, is clearly separated and sharp for the belite paste, where the peak attributed to calcite is significantly weaker. This second “calcite” step occurs as sharp peak in the temperature range 750–790 °C. The separation of vaterite and calcite is particularly clear (see the XRD and EGA data, Figs. 1 and 7) in the case of belite stabilized by Cr compound.

The result of calculations based upon the TG measurements is presented in Tables 2–4.

The TG data have been used as a base for:

- (1)

Evaluation of paste components content (Table 2)

- (2)

CaO/SiO2 determination (Table 3) and

Table 3 Estimation of the mean CaO-to-silica ratio in calcium silicate hydrate - (3)

Degree of carbonation determination (Table 4).

Table 4 Estimation of the carbonation degree of pastes

This was done under the following assumptions:

(1) dry, decarbonated residue (= ms) is composed of the following components: | |

(2) ΣCaO + SiO2 (in CSH); the total CaO/SiO2 molar ratio = 2 (as in the initial anhydrous material) | (1) |

(3) ΣCaO = CaO in calcium hydroxide + CaO in calcium carbonate + CaO in calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) | (2) |

ΣCaO = ms · 112/172 | (3) |

SiO2 (present in C–S–H only) = ms · 60/172 | (4) |

Calcium hydroxide content

• CaO amount [mg] in calcium hydroxide (portlandite), from dehydration loss = 56/18 · % dehydroxylation loss · sample mass | (5) |

• Hypothetical % of calcium hydroxide carbonated, calculated from decarbonation loss: = 74/44 · % decarbonation loss | (6) |

• Hypothetical CaO [in mg] in calcium hydroxide carbonated from % CO2 content in carbonate: = 56/44 ·carbonation loss · sample mass | (7) |

• CaO in C–S–H is calculated from the difference: ΣCaO − [CaO in calcium hydroxide + CaO in calcium carbonate] | (8) |

The calcium hydroxide content (Table 2) differs depending on the temperature of initial β-C2S synthesis. The highest level exceeding 25% can be attributed to the materials synthesized at relatively low temperature (1000 °C and 1200 °C). In turn, in the Cr-stabilized sample synthesized at 1500 °C the calcium hydroxide residue is relatively low (slightly over 10%) but accompanied by the high, over 50% calcium carbonate content. The approximate, mean CaO/SiO2 ratio (Table 3) is rather low ranging from 0.89 to 1.15 (the average is about 1.00). The lowest value (0.89) is accompanied by the highest carbonation degree. The highest hypothetical calcium hydroxide ratio released during the many-year hydration process can be attributed to the Cr-stabilized sample synthesized at 1500 °C (Table 4). Low-temperature dicalcium silicate of poorly ordered structure gives generally lower-calcium hydroxide release but higher residue, accompanied by higher CaO/SiO2 ratio in the calcium silicate hydrate, more abundant in the hydrated material (see Tables 2–4).

Conclusions

In the 40-year-old dicalcium silicate pastes, the basic anhydrous silicate is almost totally hydrated; even the poorly hydraulic γ disilicate phase is hydrated.

The main product detected in the hydrated dicalcium silicate pastes are: calcium silicate hydrate, calcium hydroxide, calcium carbonate (calcite, vaterite) and calcium silicocarbonate (tilleyite).

The CaO/SiO2 ratio in the calcium silicate hydrate product matured for 38 years is low, ranging from 0.89 to 1.15; the lowest value is found for the paste produced from belite stabilized by chromium additive and burned at high temperature. This lowest value is accompanied by the highest carbonation degree.

Depending on the initial anhydrous phase structure, as determined by the condition of synthesis, the hydration process and durability of hydration products differ significantly.

Thermally stabilized β-C2S synthesized at 1000 °C and 1200 °C shows relatively high calcium hydroxide content and low carbonation.

Belite synthesized at very low temperature (800 °C) shows high carbonation degree and low poorly crystallized calcium hydroxide content; there is also a carbonate–silicate phase formed.

The lowest portlandite stability and high carbonation degree should be attributed to the belite stabilized by Na2CrO4 and burned at 1500 °C. Calcium carbonate occurs in the form of vaterite polymorph.

γ-Ca2[SiO4] hydration products seems to be relatively stable, revealing higher C/S ratio and lower carbonation degree.

References

Kurdowski W. Cement and concrete chemistry. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer; 2014.

Neville AM. Properties of concrete. 5th ed. London: Pearson; 2011.

Geng G, Taylor R, Bae S, Hernandez-Cruz D, Kilcoyne DA, Emwas A-H, Monteiro PJM. Atomic and nano-scale characterization of a 50-year-old hydrated C3S paste. Cem Concr Res. 2015;77:36–46.

Karaś S, Klimek B. Badania stuletniego betonu z mostu na ul. Zamojskiej w Lublinie, Beton i Architektura. 2014. https://pbn.nauka.gov.pl/polindex-webapp/browse/article/article-af919486-0177-4464-a43f-76dcdef7af43. Accessed 11 Oct 2018.

Kurdowski W. Nawierzchnia betonowej autostrady sprzed 80 lat. seminarium Drogi betonowe – mądre budowanie na lata. http://www.polskicement.pl/Seminarium_BUDUJMY_DROGI_BETONOWE_TO_SIE_OPLACA_1_czerwca_2016_Kielce-378. Accessed 11 Oct 2018.

Wang Q, Feng J, Yan P. The microstructure of 4-year-old hardened cement-fly ash paste. Constr Build Mater. 2012;29:114–9.

Taylor R, Richardson IG, Brydson RMD. Composition and microstructure of 20-year-old ordinary Portland cement–ground granulated blast-furnace slag blends containing 0 to 100% slag. Cem Concr Res. 2010;40:971–83.

Jóźwiak Niedźwiedzka D, Tucholski Z. Wiadukt żelbetowy z początków XX wieku—analiza mikrostruktury stuletniego betonu (Reinforced concrete viaduct from beginning of the 20th century-microstructure analysis of 100 years old concrete). In: Drogi i Mosty (Roads and Bridges) 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268220623. Accessed 11 Oct 2018.

Jarmontowicz A, Krzywobłocka-Laurow R. Skład zapraw w murach obronnych Starego Miasta w Warszawie. In: Ochrona Zabytków. 1996. http://bazhum.muzhp.pl/media//files/Ochrona_Zabytkow/Ochrona_Zabytkow-r1996-t49-n4_(195)s359-364.pdf. Accessed 11 Oct 2018.

Schwiete HE, Kronert W, Deckert K. Existence range and stabilization of high-temperature modifications of dicalcium silicate. Zement-Kalk-Gips. 1968;83:359–66.

Gawlicki M, Nocuń-Wczelik W. L’influence du traitement thermique sur la transition β->γ-Ca2SiO4. In: Proceedings of 7th international congress on the chemistry of cement. Paris; 1980. p. 161–5.

Kurdowski W, Duszak S, Trybalska B. Belite produced by means of low-temperature synthesis. Cem Concr Res. 1997;27:51–62.

Gawlicki M. Stabilizacja termiczna β − Ca2SiO4—thermal stabilization of β − Ca2SiO4. Polski Biuletyn Ceramiczny/Polish Ceramic Bulletin. Ceramika. 2008;103(2):989–96.

Tantawy M. Influence of silicate structure on the low temperature synthesis of belite cement from different siliceous raw materials. J Mater Sci Chem Eng. 2015;3:98–106.

Ávalos-Rendón TL, Pasten Chelala EA, Mendoza Escobedo CJ, Figuero IA, Larac VH, Palacios-Romero LM. Synthesis of belite cements at low temperature from silica fume and natural commercial zeolite. Mater Sci Eng. 2018;229:79–85.

Pritts M, Daugherty KE. The effect of stabilizing agents on the hydration rate of β-C2S. Cem Concr Res. 1976;6:783–95.

Fierens P, Tirlocq J. Effect of synthesis temperature and cooling conditions of beta–gamma dicalcium silicate on its hydration rate. Cem Concr Res. 1983;13:41–8.

Gawlicki M. Aktywność hydrauliczna modyfikowanego β-Ca2[SiO4] (Hydraulic activity of modified β-Ca2[SiO4]). Kraków: Polish Academy of Science; 2008.

Fang Yanfeng, Chang Jun. Rapid hardening β-C2S mineral and microstructure changes activated by accelerated carbonation curing. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2017;129:681–9.

Gaviria X, Borrachero MV, Payá J, Monzó JM, Tobón JI. Mineralogical evolution of cement pastes at early ages based on thermogravimetric analysis (TG). J Therm Anal Calorim. 2018;132:39–46.

El-Gamal SMA, Abo-El-Enein SA, El-Hosiny FI, Amin MS, Ramadan M. Thermal resistance, microstructure and mechanical properties of type I Portland cement pastes containing low-cost nanoparticles. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2018;131(2):949–68.

Nocuń-Wczelik W. Some factors affecting the tricalcium silicate hydration. Ph.D. Thesis. Kraków; 1984.

Acknowledgements

The financial support from the Faculty of Material Science and Ceramics, University of Science and Technology AGH, Cracow, Poland, is greatly acknowledged (Grant No 11.11.160.557).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Murzyn, P., Malata, G., Wiśniewska, J. et al. Characterization of 40-year-old calcium silicate pastes by thermal methods and other techniques. J Therm Anal Calorim 138, 4271–4278 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08519-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08519-8