Abstract

Prayer, considered by some to be the essence of religion, has been a universal behavior throughout human history. Scholars have increasingly recognized that there are different types of prayer and various prayer purposes, but little work has been done to examine their mental health consequences beyond an examination of prayer frequencies. In this study, we draw on nationally representative data from Wave 6 of the Baylor Religion Survey (2021) to examine whether four subtypes of prayer are associated with anxiety: prayer efficacy (the belief that prayer can solve personal and world problems); devotional prayer (praise of God and prayer for the well-being of others); prayers for support (e.g., better health, financial aid); and prayer expectancies (whether God answers prayers). Results suggest that prayer efficacy, prayers for support, and one form of devotional prayer (asking God for forgiveness) all correlate with higher anxiety, while another form of devotional prayer (praise of God) and prayer expectancies are associated with lower anxiety in the American population. We note the importance of capturing multidimensional phenomenon that comprise religious prayer life within the extensive religion and health literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prayer, considered by some to be the essence of religion, has been a universal behavior throughout human history (Levin & Taylor, 1997; Woodhead, 2016). At its core, prayer can be defined as “communication addressed to God” (Stark, 2017, p. 45), where an individual can externalize their concerns, intentionally relate to others, and attempt to see reality through the eyes of God or a divine being (Woodhead, 2016, p. 224–225). William James (1902) offered a broad definition of prayer, suggesting that prayer was “every kind of inward communion or conversation with the power recognized as divine” (p. 464). In this sense, prayer is an experience through which believers interact with the divine. Although there is considerable variability in prayer experiences, some practitioners have reported that they can literally hear God “talking back” (Luhrmann, 2012).

Over the course of the last several decades, researchers have made considerable strides in the study of prayer. As this literature began to develop, it became quickly evident that prayer is a vast, multidimensional phenomenon (see Froese & Uecker, 2022). Early investigators, for instance, identified different types of prayer, such as ritual, conversational, petitionary, and meditative prayer (Poloma & Gallup, 1991). Alongside research on the types and forms of prayer, theories about how prayer may affect well-being also began to emerge in the literature as well (Baesler et al., 2011; Breslin & Lewis, 2008). Results from existing work on prayer and mental health have been somewhat inconsistent. Indeed, some prior cross-sectional studies point to the beneficial associations of prayer with mental health (Ai et al., 1998; Ellison & Taylor, 1996; Levin, 1996), while others find that prayer may be linked to worse mental health outcomes (Bartkowski et al., 2017; Hank & Schaan, 2008). Quantitative studies of prayer and well-being tend to measure prayer in terms of simple frequencies that fail to represent the variegated experience of this phenomenon. If the effects of prayer are conditional on the type of prayer or perceptions of the divine object of prayer, the limited measurements of previous work may obscure our understanding of the complex relationship between prayer and mental health.

In a recent review article, Froese and Jones (2021) suggest that prayer may include at least four dimensions: (1) prayer quantity, including issues such as prayer frequency and consistency, (2) prayer style, or the behavioral rules and norms that underlie prayer, (3) prayer purpose, or what one wishes to accomplish via their prayers, and (4) prayer targets, the supernatural entities that are prayed to. In this study, we center in on the latter two dimensions of prayer through the use nationally representative data from Wave 6 of the Baylor Religion Survey (2021), which provides an unprecedented opportunity to move beyond simple prayer frequencies. Specifically, we look at four subtypes of prayer, including prayer efficacy (the belief that prayer can solve personal and world problems), devotional prayer (praise of God and prayer for the well-being of others), prayers for support (e.g., better health, financial aid), and prayer expectancies (whether God answers prayers). As we outline below, each dimension of prayer may be connected to anxiety in unique ways, in both positive and negative directions.

Our reasons for centering on prayer and anxiety are twofold. First, anxiety-related issues are common in the United States, with approximately one in five Americans suffering from anxiety disorders (Horwitz, 2013). Second and more substantively, researchers of religion/spirituality have focused heavily on certain outcomes (e.g., depression and life satisfaction), but far fewer studies have concentrated on other important emotional states, such as anxiety. Thus, after laying out the reasons why prayer typically shows an inconsistent relationship with mental health, we devote significant space to understanding how prayer type, as a feature of this broader religious activity, may correlate with anxiety, a vastly understudied outcome, in the American populace.

Literature Review

Theoretical Models of Prayer and Well-Being

Dating back several decades ago, McCullough (1995) suggested that physiological and psychological spiritual pathways could explain why prayer may be associated, for better or worse, with mental health. McCullough (1995) posited that prayer may activate health-promotive psychological mechanisms such as structure, meaning and hope. In other words, prayer may be useful insofar as it changes the ways in which individuals appraise stressful events. Finney and Malony (1985) suggested that contemplative prayer involves hypnotic suggestion, and a condition of a lower level of arousal through inducing a state of relaxation. The act of prayer has been found to lead directly to a lower heart rate, reduced muscle tension, and slower breathing rate (McCullough, 1995). Clinical studies have also suggested that prayer may also contribute to feelings of tranquility by altering brain chemistry and structure (Newberg & Waldman, 2009). Levin (2020, p. 105) summarizes research which finds a wide swathe of other physiological and neurological outcomes of prayer, including decreased sympathetic nervous system activity, and increased parasympathetic activity (e.g., the opposite of the fight-or-flight response). Taken together, these studies suggest that prayer may put us into a calm or relaxed state by prompting changes in brain chemistry and structure (Levin, 2020).

In addition to these physiological mechanisms, the psychological belief that God provides answers could provide rest, inspiration, and a sense of intimacy that can help to ease the burden of stress and provide a sense of purpose in life (McCullough, 1995). As Levin (2020, p. 61) notes, prayer can promote a transcendent experience which “typically evokes a perception that human reality extends beyond the physical body and its psychosocial boundaries” (Levin, 2020, p. 61). According to Levin (1996), hope, love, contentment, empowerment, and other positive emotions might flow from prayer. Prayer may thus foster psychological benefits by creating a positive sense of meaning, hope, and empathy (Levin, 1996; McCullough, 1995). Prayer can also provide a framework for thinking about life and processing the outcomes of life (Ellison, 1995) and cross-sectional research has shown that it may be used as a coping tool that can aid believers in confronting a certain stressor or in overcoming negative emotions (Bade & Cook, 2008; Masters & Spielmans, 2007; Rainville, 2018; Sharp et al., 2016). Conti and colleagues (2003) even suggest that prayer is analogous to a form of psychotherapy in helping people to redefine stressors in less threatening ways through sharing them with a divine power and helping them derive meaning in the face of hardship (see also Ellison & Taylor, 1996).

As mentioned at the outset of this study, prayer does not have an unequivocally positive relationship with mental health. From a physiological standpoint, some purposes of prayer have been found to be damaging to the brain if they are focused on elements of fear or anger (Newberg & Waldman, 2009). A unique challenge when studying prayer is that “individuals confronting high levels of stress and distress pray more often” (Bradshaw et al., 2008, p. 654). While prayer as a form of religious coping may help reduce the effects of stress, findings from both cross-sectional (Ellison et al., 2014) and longitudinal studies (Bradshaw & Kent, 2018) suggest that praying to a God who is perceived to be distant and cold undermines the sense of security and significance, and could actually increase psychological distress and anxiety.

Perhaps due to this dual process of prayer fostering both positive and negative physiological and psychological processes, at least one cross-sectional study found that prayer frequency is unrelated to anxiety (Ellison, Hill, & Burdette, 2009). Ellison and colleagues (2009) suggest incorporating varieties of prayer types in order to understand which ones are associated with the greatest reductions in anxiety. Therefore, the relationship between prayer and mental health may depend on the extensive variation in prayer experiences, which we outline below. As Brown (1994) argues, what individuals pray about is much more important than how often they do it. Put another way, why someone is praying could matter more than the quantity of prayer.

Prayer Purpose & Intentions

The purpose of prayer accesses why practitioners say they enter into prayer and seeks to capture their explicit motivations for engaging in this religious activity. According to Froese and Jones (2021), prayer purpose/intention represents the “rational” aspect of prayer, gauging how practitioners rationalize the activity of prayer to themselves.

One of the basic stated purposes of prayer is that supplication to and communication with God should produce positive individual and social outcomes. For the purposes of our study, we term this prayer efficacy. Hunter (1990) demonstrated that a majority of Americans felt that prayer before government sessions, sporting events, and school activities leads to greater success. It is possible that using prayer as a vehicle to solve both individual and world problems might be associated with lower anxiety. Equipped with the hope of a positive end result, prayers for assistance to problems at the personal or global level might be helpful in reducing anxiety, at least temporarily.

Beyond asking for aid in solving problem, other types of prayer are perhaps more idiosyncratic. Prayers of petition are ones in which the believer asks God to grant them a blessing in this world to fill some specific need, while prayers of intercession ask God to grant a blessing to another person beyond the individual (Janssen et al., 1990). We divide this larger category of petitionary prayer into Devotional Petitions (e.g., asking God for forgiveness, praising God, or praying for the well-being of others) and Prayers of Support (e.g., asking God for guidance in decision-making, support for relationships, better health, and financial help).

As a class of prayers, petitionary prayers introduce the idea of a transaction in one’s relationship with God and raise the question of whether God will respond to prayer requests. Asking God for something concrete—be it His forgiveness, good health, or economic aid, for instance, could help to ease some of the anxiety associated with those problems. Sharp (2012, p. 257) notes that having “prayed over” a decision helps to “prevent possible negative characterization,” because the act of prayer helps to give moral legitimacy to whatever decision is rendered. However, the content of petitionary prayers also maps directly onto the type and severity of individual life problems that are being experienced. For example, petitionary prayer is most common among disadvantaged members of American society, including African Americans and those with lower education and lower income (e.g., Baker, 2008; Krause & Chatters, 2005; Spilka et al., 2003). Better health is one of the most commonly made requests through petitionary prayer, as nearly three-quarters of Americans pray for their general health (Brown, 2012).

Therefore, to the extent that good health, forgiveness, financial prosperity, support with intimate relationships, and guidance in decision-making are the primary purposes of prayer, this may be indicative of a person experiencing unusually high amounts of stress, perhaps correlating with higher anxiety. One prior study by Winkeljohn-Black and colleagues (2015) found neither a positive nor negative relationship between petitionary prayer and mental health. These authors suggest that this lack of relationship between mental health and petitionary prayer can be explained by the prayer’s lack of meaningful disclosure to God, a topic which we explore in the next section.

Prayer as Interaction with God

An additional component of prayer could be to offer praise or otherwise deepen a relationship with God or a divine being. Most Americans see themselves as having a two-way, relationally engaged bond with God (Hall & Fujikawa, 2013), a relationship where God speaks to them through prayer (Luhrmann, 2012), is actively involved and intervened in their lives (Froese & Bader, 2010), and collaborates with them to solve problems (Krause, 2005). Stark (2017) argued that one of the primary purposes of prayer is to strengthen the relationship between the believer and the divine.

Recent scholarship by Luhrmann et al. (2010) maintained that one’s perception of God’s character is cultivated over time through prayer. The experience of prayer may also determine how God is perceived, which affects the feelings that may be experienced during prayer and the eventual affective outcomes. For instance, the link between a higher frequency of prayer and greater distress exists among people who perceive God as remote and do not view God as loving (Bradshaw & Kent, 2018; Bradshaw et al., 2008). In addition, perceptions of an angry God may inspire feelings of anxiety, while beliefs in a caring God may promote optimism and a sense of agency (Liu & Froese, 2020), both of which might benefit mental health.

We focus on prayers of adoration toward God, which involve praise of and interaction with God, as a form of devotional prayer. Prayers of adoration have the psychological benefit of lifting individuals out of themselves and diminish egocentricity (Watts, 2001). Watts (2001) claims that it is psychologically freeing for individuals to open their hearts to God in an act of unwavering appreciation. This form of prayer may help individuals to calm both their mind or body and can help the process of stress recovery. Meisenhelder and Chandler (2001) suggested that this form of prayer is beneficial to mental health because this praise may strengthen one’s relationship with God, fostering a deeper sense of love and appreciation for the divine being. Offering prayers of praise to God as a form of devotion may also increase confidence that the person is praying in accordance with the will of God (Henning, 1981), rather than petitioning for outcomes to happen according to their own timeline. Altogether, prayer with the aim of showing devotion to God could decrease anxiety by reminding individuals that there is a God who cares about our worship.

Prayer-Based Expectancies

As a final dimension considered in the current study, prayer is often undertaken with an expectation of desired outcomes from God. Many believers hold expectations about whether their prayers are answered, how quickly prayers are answered, and how prayers are ultimately answered by God (e.g., Krause et al., 2000). Existing research focused on prayer expectancies reveal that if people get what they expect, they may experience an enhanced sense of well-being, but if expected outcomes fail to arise, people may feel psychological distress (Olson et al., 1996).

Though research on prayer-based expectancies is somewhat limited, older people who endorse trust-based expectancies (that God knows how to best answer prayers and does so in His own time) had higher self-esteem and life satisfaction (Krause, 2004; Krause & Hayward, 2013). Such trust-based prayer-expectancies ae unlikely to be invalidated because individuals are willing to wait for a response from God and may accept responses that differ from their initial request. According to these studies, what one expects from prayer may bear close connection with affective outcomes that may stem from prayer, including anxiety.

Some scholars have also hinted at the downsides of unfulfilled prayer expectancies. For example, Epperly (1995) argued that prayer may pose threats to well-being if answers to prayers are viewed solely as a reflection of God’s arbitrary will. If prayers being answered according to human requests are a precondition for viewing God as loving, this may create a dangerous scenario in which a person may only love and trust God if they get the desired responses and feel they are important to God. This claim has been corroborated in prior research, as a study by Exline and colleagues (2021) found that if participants saw God as more responsive to their prayers, they reported less doubt about God’s existence, felt less distant from God, and perceived God as less cruel. The corollary, however, is that if individuals believed God was not responsive to their prayers, their relationship with God tended to be more negative. In her work, Luhrmann (2012) is careful to remind researchers that not all prayer should seek a response back from God. Indeed, when the prime goal of prayer is for God to respond in direct and concrete ways specified by humans, too much emphasis is placed on “outer effects” (Giordan, 2016). Therefore, we might expect, to the extent that individuals expect to receive answers from God to their prayers, this may actually foster higher anxiety, especially if the responses do not align with the recipient’s intentions.

Methods

We use data from the 2021 Baylor Religion Survey, which was administered by Gallup. Data collection lasted from January 27 to March 21, 2021, during which time 11,000 surveys were sent out to 50 US states and the District of Columbia using an address-based sampling technique. Data were collected with either a mailed or an online questionnaire, which were available in both English and Spanish. The result was a random sample of 1248 US adults. The response rate for the survey was 11.3%. This survey was selected since it was collected recently, is nationally representative, and offers unique measures targeting several aspects of prayer along with items for constructing an index of anxiety.

To be eligible for inclusion in our sample and respond to the Baylor Religion Survey Prayer Module questions, respondents had to report praying outside of religious services. Of the 1206 respondents who gave valid responses to the prayer frequency question, 289 reported never praying, yielding a final analytic sample of 917. Removing all cases with missing data using listwise deletion, we are left with a final sample of 823 respondents for analysis.

Dependent Variable: Anxiety

Three items were used to assess the respondents’ anxiety level. Respondents were asked, “In the past week, how often have you had the following feelings?” Subsequent statements included “I worried a lot about little things,” “I felt tense and anxious,” and “I felt restless.” Again, the answer categories were (1) “never”, (2) “hardly ever”, (3) “some of the time”, and (4) “most of the time”. Responses to these three questions were summed, with a higher score corresponds with a higher anxiety level. This anxiety scale has an alpha reliability coefficient of 0.83.

Key Independent Variables: A Variety of Prayer Dimensions

Several variables assessing prayer type were used in the current. The first two variables assess the extent to which a person agrees with the following statements about prayer efficacy: (1) “I pray because prayer is the best way to solve world problems,” and (2) “I pray because prayer is the best way to solve personal problems.” Responses to both of these items were scored where 1 = “Strongly disagree” (reference category), 2 = “Disagree,” 3 = “Agree,” and 4 = “Strongly agree.”

The next three variable target devotional/intercessory prayer. The first item asks respondents their agreement with the following statement: “I pray to ask God for forgiveness,” coded from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 4 = “Strongly agree.” The second two items ask respondents how often they use prayer to “praise God” and “pray for the well-being of others,” with both items coded in the following way: 1 = “Never,” 2 = “Rarely,” 3 = “Some of the time,” 4 = “Much of the time,” and 5 = “All of the time.”

Our next set of four prayer variables indicate how often a respondent prays for support. These variables are based on the frequency (from 1 = “Never” to 5 = “All of the time”) that a respondent, through prayer, asks for “guidance in decision-making,” “support with relationships,” “better health,” and “financial help.”

Finally, our last measure of prayer captures prayer-based expectancies from God by assessing agreement/disagreement with the statement “I pray because God answers my prayers.” This measure is coded from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 4 = “Strongly agree.”

Covariates

To ensure that any association between prayer type and mental health was not confounded by other variables that could also predict anxiety, we controlled for several demographic variables, including gender (female = 1), age (years), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and Other race), marital status (married or in a cohabiting partnership = 1), and education (college degree = 1). Respondents also reported on their total household income last year (before taxes) from 1 = $10,000 or less, 2 = $10,001–$20,000, 3 = $20,001–$35,000, 4 = $35,001–$50,000, 5 = $50,001–$100,000, 6 = $100,001–$150,000, and 7 = $150,001 or more. We also included adjustment for the region of the country that the respondent lived in (Northeast, South, Midwest, and South).

Analyses also adjusted for two additional religious covariates in all statistical models. First, religious attendance was assessed by the question, “How often do you attend religious services at a place of worship?” This was coded into a four-category variable, where 1 = Never attends, 2 = Attends yearly, 3 = Attends monthly, and 4 = Attends weekly or more. Analyses also adjust for religious tradition following the RELTRAD scheme proposed by Steensland et al. (2000), which categorizes individuals into Evangelical Protestants (reference group), Mainline Protestants, Black Protestants, Catholic, Jewish, Other religion, and the non-affiliated.

Plan of Analysis

We estimate a series of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models to assess the associations of prayer type and anxiety. All regression models use weighted data to enhance representativeness of parameter estimates. After presenting sample descriptive statistics (Table 1) and descriptive statistics for all prayer variables (Table 2), we present results for each category of prayer type (Tables 3, 4, 5, and 6). In the interest of space, we do not show results for the covariates in each table (but results are available upon request).

Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for all non-prayer related study variable. Of note, the BRS Wave 6 sample had average anxiety scores of 7.22 (SD = 2.35) and ranged from 3 to 12. We would also note that over half of our sample had a college degree, and about one-quarter of our sample reported attending religious services weekly.

More germane to our central research questions, we also show in Table 2 the percentage of BRS-6 respondents who expressed agreement/disagreement with each of the prayer prompts, as well as the frequencies of specific prayer types. As can be seen there with our two measures of prayer efficacy, more than two-thirds of the sample (66.63) expressed at least some agreement that prayer is the best way to solve world problems. A higher percentage of respondents (74.84%) expressed at least some agreement that prayer is the best way to solve personal problems.

For devotional/intercessory prayer, more than 80% of the sample reported that they pray to ask for God’s forgiveness. Almost two-thirds of the sample reported praising God either “much of the time” or “all of the time” in prayer, and over three-quarters of the sample reported that they regularly (much or all of the time) used prayer to pray for the well-being of others.

Across the four types of support that respondents could report praying for, respondents were most likely to regularly ask for guidance in decision-making (63.31%), followed by support with relationships (47.29%), then better health (43.05%), and finally, they were least likely to regularly ask for financial help (22.68%).

As for our last category of prayer examined, prayer-based expectancies, over three quarters of the sample (76.56%) reported at least some agreement that God answers their prayers. With these descriptive statistics laid out, we now move to our regression analysis, where these various types of prayer are regressed on anxiety and a host of demographic and religious control variable.

Multivariable Regression Results

Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6 show results for each category of prayer variables outlined above. Beginning with measures of prayer efficacy in Table 3, we see that agreement with the statement “I pray because prayer is the best way to solve world problems” was not significantly associated with anxiety. However, stronger agreement that prayer is the best way to solve personal problems was significantly associated with higher anxiety, with those agreeing (b = 0.85, p < 0.05) and strongly agreeing (b = 0.74, p < 0.05) with that statement more likely to report higher anxiety than those disagreeing with that statement.

Moving to the results for devotional/intercessory prayer shown in Table 4, we see that stronger agreement that prayer is used as a means to ask forgiveness with God is also associated with higher anxiety (agree: b = 0.88, p < 0.05, strongly agree: b = 0.84, p < 0.05). However, a higher frequency of prayer that is used to praise God was found to be significantly associated with lower anxiety, for respondents reporting praising God much of the time (b = −0.23, p < 0.05) and all of the time (b = −0.20, p < 0.05) relative to those who never praised God in prayer. Finally, in the last model of Table 4, we see that no frequency of prayer for the well−being of others significantly correlated with the anxiety of the respondents.

Table 5 shows results for the four different types of prayer support we examined in this study. Guidance in decision-making was observed to have a null association with anxiety, as was asking for support with relationships through prayer. Respondents who more frequently prayed for better health (“all of the time”) (b = 0.45, p < 0.05) and financial help (b = 0.36, p < 0.05) reported higher anxiety relative to those who never asked for these types of support via prayer. Post-hoc tests also showed that those who frequently prayed for better health and financial help also reported higher anxiety than BRS respondents who prayed for support “some of the time,” but this highest frequency group did not have anxiety scores that differed from those who asked for these two types of support “much of the time.”

Finally, Table 6 shows results from a model that shows how prayer-based expectancies, that God answers prayers, is associated with anxiety. As we see there, stronger agreement with the statement, “I pray because God answers my prayers” is associated with lower anxiety for those who agree (b = −0.88, p < 0.05) and strongly agree with this statement (b = −0.80, p < 0.05). In the discussion section that follows, we unpack these findings across these four categories of prayer types and purposes.

Supplemental Analyses

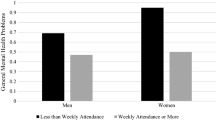

On almost every dimension of religiosity, women tend to be more religious than men (Schnabel, 2015, 2018), and report a higher frequency of prayer than men (Maselko & Kubzansky, 2006). It has also been suggested that women report higher levels of intimacy with God (Kent & Pieper, 2019) which is an important component of prayer. Previous work by Kent (2020) women that prayer was either non-significant or associated with lower depressive symptoms for women but was associated with higher depressive symptoms for men. We therefore examined in ancillary analyses whether the results we observed in our main analyses had gender contingencies. To do this, we examined if each of the ten dimensions of prayer (grouped into four types of prayer) significantly interacted with gender (male = 0, female = 1) in their associations with anxiety. In no case was a significant interaction term detected. Therefore, on the basis of these supplemental analyses, we did not find evidence that our main findings differed by gender. We return in the discussion section to recommend further analyses on potential status-based differences in the relationship between prayer and anxiety.

Discussion

Prayer occupies a core position in religious life, a sentiment which earlier social theorists like William James (1902) clearly recognized this when he said, “Prayer is religion in act; that is, prayer is real religion” (p. 464). James (1902) argued that prayer feels like a true conversation or transaction between the person who prays and the divine being that is being prayed to. Despite this central importance of prayer, the sociology and psychology of religion appears somewhat stunted in its study of prayer, particularly in considering measures beyond the frequency of private prayer measured commonly in survey research. Within the religion and health literature, the results from studies on prayer and mental health have been mixed, with some studies identifying a beneficial association of prayer with mental health (Ai et al., 1998; Ellison & Taylor, 1996; Levin, 1996, 2020), and others showing prayer to be linked to unfavorable mental health outcomes, such as lower anxiety (Bartkowski et al., 2017; Hank & Schaan, 2008). We suspect that what may underlie these discrepant set of findings could be the measures and aspects of prayer that were examined. Indeed, not all types and forms of prayer may elevate a person’s mental well-being, and it is possible that some may even be deleterious. To provide a broad scope of the implications of prayer for mental health, the current study drew from a nationally representative sample of Americans and examined ten different types of prayer types/purposes, which we broke down into four sub-categories: prayer efficacy, devotional/intercessory prayer, prayers of support, and prayer expectancies. As our results show, these various types of prayer held both positive and negative associations with anxiety for reasons we expound on below.

A series of key findings emerged from our study looking at the various types of prayer and their association with anxiety. First, with regard to prayer efficacy (what people believe prayer can accomplish), we found that stronger agreement with prayer as the solution to personal problems was associated with higher anxiety. A similar finding was not observed for believing that prayer is the best solution to problems of the world. It is possible that world problems may seem too far removed from the perceived effects of personal prayer, and hence bear no association with mental health problems. However, people who report that prayer represents the best solution to personal problems may do so because they are facing a high volume of earthly problems with no other solution. Because we relied on cross-sectional data, we cannot disentangle whether current hardships may select people into different types of prayer, but to the extent that prayer represents a coping response to stress, seeing prayer as a solution to one’s personal problems appears to promote higher anxiety.

This finding also dovetails with our results pertaining to prayer and support. Indeed, people who more often sought support with their health and finances through prayer also reported higher levels of anxiety. Turning to prayer when faced with these difficulties could be an enactment of religious coping or could be a frustrating endeavor if there is no improvement in one’s health or financial situations, leading people to question whether their prayers to God are in vein (e.g., DeAngelis et al., 2019). Taken together, more frequent prayer in the midst of personal problems appears to associate with higher anxiety relative to less frequent prayer, perhaps amplifying the angst felt by the experience of life stressors.

Several of our findings related to prayer can also be interpreted in light of a person’s relationship with God. Many religious believers in the United States engage in prayer to deepen their relationship with God (Stark, 2017), where God is perceived to speak to them through prayer (Luhrmann, 2012). Prayers of devotion and adoration toward God involving prayer were associated with lower anxiety in our sample. Prayers of adoration have the benefit of shifting the focus from the individual to a more transcendent entity, which could help individuals place their personal problems in a different perspective. Prayers of adoration have been found in previous research with small samples to have a negative relationship with anxiety (Maltby et al., 1999) and a positive association with overall well-being (Maltby et al., 1999), and we show this to be the case here using a larger, nationally representative sample.

Some of our other findings surrounding the prayer target of God also hint that the eventual affective outcomes of prayer may be dependent on how God is approached in prayer. For instance, believers who more often sought forgiveness from God through prayer reported higher anxiety. It is possible that the need to seek forgiveness from God might indicate transgressions on the part of the individual that they believe can be damaging to their overall relationship with God, causing anxiety as to how God will respond. Prior work has found that for those with a distant relationship from God, personal well-being is maximized if forgiveness is sought less (Kent et al., 2018), and our results support this finding that seeking out forgiveness may be associated with higher anxiety, perhaps as a response is awaited.

It is also worthy of mention that we found that petitionary prayer, that is, prayer for the well-being of others, was not associated with anxiety in either a positive or negative direction. One prior study has found that petitionary prayer is associated with more mental health problems, while another study found no association (Maltby et al., 1999; Winklejohn Black et al., 2015). Because the targets of intercessory prayers are outside of the individual’s self, we may not expect to see strong associations with anxiety, which is experienced as an individual outcome. This does not preclude the possibility, however, that praying for others may be associated for other outcomes that may underlie well-being, such as optimism or empathy.

Our final result was that stronger agreement that God answers one’s prayers is associated with lower anxiety. Prayer can sometimes be undertaken with the explicit desire to receive a response from God. Some research suggests that fail to receive an answer from God may lead to heightened distress (Olson et al., 1996), while other studies show that trusting God to answer prayers in His own way and according to His timeline are associated with higher well-being (Krause, 2004; Krause & Hayward, 2013). We show that the belief that God answers prayers is associated with lower anxiety. While our measure of prayer expectations lacks a deeper consideration of whether the person views the answers they receive as coming in a timely fashion and reflecting their inner desires, the mere acknowledgement that God answers prayers was observed to be efficacious.

We interpret this finding in light of previous research that has considered the intersection of prayer with one’s attachment to God. The belief that God answers prayers may be one component of what scholars have termed attachment to God. Granqvist and Kirkpatrick (2016) theorize that individuals with higher secure attachment to God, that God is emotionally responsive to them and a secure base from which to view the world, will feel a great deal of emotional safety and assurance when God is their specific prayer target and report better mental health outcomes (Bradshaw & Kent, 2018; Ellison et al., 2014). Prior work has found that seeing God as unresponsive to one’s prayers is associated with viewing God as distant and cruel (Exline et al., 2021) and could thus undermine mental well-being. If God is viewed as responsive to prayers, it follows that people should feel less anxiety because they have a trusted confidant to turn to.

Unlike the relationship between other commonly studied religious variables, such as religious attendance and health, our findings from a wide range of prayer measures show that the relationship between prayer and mental health is less straightforward. As a whole, our study shows that not all forms of prayer are created equal, and that an even more complex picture emerges when we move beyond the limits of examining only prayer frequency to encompass various types of prayer. Painting with broad strokes, prayer appears to be associated with better mental health if it facilitates and reinforces a positive relationship with a perceived divine other (God) through praise or belief that one’s prayers are answered (e.g., Whittington & Scher, 2010). It is likely that reinforcing a close connection with a perceived personal God through frequent prayer can bolster some aspects of the self, perhaps by increasing self-esteem or the sense of mattering (e.g., Ellison, 1993; Schieman et al., 2010). On the other hand, prayer tends to be associated with worse mental health if it arises out of a troubled relationship with God, or if prayer is used as a resource of coping during periods of high stress.

Limitations

Despite the numerous dimensions of prayer experience that were considered in the current study, it is not without limitations. First and foremost, we were limited to the use of cross-sectional data, which does not allow us to extract conclusions regarding causality. As was implied with several of the prayers of support dimensions, prayer is often a response to negative life events or significant hardship. The differences in prayer style chosen by the respondents may be a result of the social contexts people find themselves in, such that devotional/intercessory prayer is sought out by those facing hardship, while prayers of adoration may be more likely to be prayed by those experiencing fewer struggles in their lives. It is therefore also possible that a person who feels more anxious is more likely to pray to God. Ultimately, longitudinal studies will be needed to sort out the temporal direction of stressors, prayers, and mental distress. And as Levin (2020, p. 86) warns, scientific methods “cannot possibly prove or disprove actions of a presumably supernatural being that may exist in part outside of the physical universe.” Thus, any relationship between prayer and well-being are only within the purview of social association.

Second, we also acknowledge that the majority of our sample were Christian respondents from the United States. The results of this study should therefore not be generalized to people of other religious affiliations. It should also be in the interest of future research to obtain more diverse samples to determine whether our findings are robust across other ethnic and religious groups, especially given the importance of private prayer to religious life in countries where formal religious attendance may be quite low.

Third, our data were collected roughly 1 year into the COVID-19 pandemic in the early months of 2021, which could have also factored into our results. For example, Bentzen (2021) noted a 50% increase in Google searches for topics related to prayer at the start of the pandemic in 2020. If Americans were in fact praying more than previous time periods because of increased hardships and out of greater anxiety about what the future holds, this could have affected our results, particularly with prayers offered for better health and financial aid as well as to solve personal problems. Our results should therefore be replicated with more recent data as the pandemic wanes. Additionally, we acknowledge a lower response rate (11.3%) in the BRS-6. Since the survey was fielded during the COVID-19 pandemic, many areas experienced significant postal delays related to the pandemic. This likely had an impact on response rates, and Gallup did see a significant decline in response rates on other mail surveys fielded during the pandemic.

Researchers who consider replicating the current study in its examination of multiple types of prayer may also wish to consider several moderating variables that could be of importance. For instance, studies looking at the demographic correlates of prayer frequency show that women pray more often than men (Schnabel, 2015) and that Black individuals tend to pray more than White individuals (Baker, 2008; Levin & Taylor, 1997). Despite these differences in prayer frequency, and while supplemental analyses showed no gender-based contingencies in the association between prayer types and anxiety, a closer investigation of which types of prayer may matter more or less for the mental health of women and Black Americans is worthy of further study, ideally with longitudinal data.

Finally, future investigations may also profitably consider whether how a person sees their communication with God (i.e., as one-way or two-way) and the person’s perceived relationship with God as possible moderators between prayer type and mental health as well. Froese and Bader (2007, 2010), for instance, have noted the diversity in images of how people see God, and these diverse images may account for diversity in types or purpose of prayer. Though beyond the scope of the current study, future work could build on the current findings by considering participants’ images of God as an additional modifier, with positive images of God expected to be more strongly associated with better mental health for types of prayer that bore salubrious associations with anxiety, and more negative or punitive images of God expected to exacerbate any ill effects of prayer for mental health.

Conclusion

Prayer occupies a prominent place in the study of religiosity. At its core, prayer is an aspect of religious life that exemplifies its very personal, individualized dimension that centers on an individual’s interaction with a perceived deity. Prior research on how prayer is connected with mental health, almost exclusively focusing on the frequency of private prayer, has revealed divergent patterns of both salubrious and detrimental associations with mental well-being. Casting a wide net and examining several types of prayer, our findings exemplify finer grained nuances in the relationship between prayer and well-being. Future research is needed to further understand the complex relationship between prayer and mental health, but we hope that these findings launch an array of studies that move beyond the limits of examining prayer frequency to better capture the multidimensional phenomenon that is religious prayer life within the extensive religion and health literature.

References

Ai, A. L., Dunkle, R. E., Peterson, C., & Boiling, S. F. (1998). The role of private prayer in psychological recovery among midlife and aged patients following cardiac surgery. The Gerontologist, 38(5), 591–601. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/38.5.591

Bade, M. K., & Cook, S. W. (2008). Functions of Christian prayer in the coping process. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 47(1), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2008.00396.x

Baesler, E. J., Lindvall, T., & Lauricella, S. (2011). Assessing predictions of relational prayer theory: Media and interpersonal inputs, public and private prayer processes, and spiritual health. Southern Communication Journal, 76(3), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/10417940903474438

Baker, J. O. (2008). An investigation of the sociological patterns of prayer frequency and content. Sociology of Religion, 69(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/69.2.169

Bartkowski, J. P., Acevedo, G. A., & Van Loggerenberg, H. (2017). Prayer, meditation, and anxiety: Durkheim revisited. Religions, 8(9), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8090191

Bentzen, J. S. (2021). In crisis, we pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 192, 541–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.10.014

Bradshaw, M., & Kent, B. V. (2018). Prayer, attachment to God, and changes in psychological well-being in later life. Journal of Aging and Health, 30(5), 667–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264316688116

Bradshaw, M., Ellison, C. G., & Flannelly, K. J. (2008). Prayer, God imagery, and symptoms of psychopathology. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 47(4), 644–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2008.00432.x

Breslin, M. J., & Lewis, C. A. (2008). Theoretical models of the nature of prayer and health: A review. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 11(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670701491449

Brown, L. B. (1994). The human side of prayer. Religious Education Press.

Brown, C. G. (2012). Testing prayer: Science and healing. Harvard University Press.

Conti, J. M., Matthews, W. J., & Sireci, S. G. (2003). Intercessory prayer, visualization, and expectancy for patients with severe illnesses: Implications for psychotherapy. Annals of the American Psychotherapy Association, 6(4), 20–28.

DeAngelis, R. T., Bartkowski, J. P., & Xu, X. (2019). Scriptural coping: An empirical test of hermeneutic theory. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 58(1), 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12576

Ellison, C. G. (1993). Religious involvement and self-perception among Black Americans. Social Forces, 71(4), 1027–1055. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/71.4.1027

Ellison, C. G. (1995). Race, religious involvement and depressive symptomatology in a southeastern US community. Social Science & Medicine, 40(11), 1561–1572.

Ellison, C. G., & Taylor, R. J. (1996). Turning to prayer: Social and situational antecedents of religious coping among African Americans. Review of Religious Research, 38(2), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.2307/3512336

Ellison, C. G., Burdette, A. M., & Hill, T. D. (2009). Blessed assurance: Religion, anxiety, and tranquility among US adults. Social Science Research, 38(3), 656–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.02.002

Ellison, C. G., Bradshaw, M., Flannelly, K. J., & Galek, K. C. (2014). Prayer, attachment to God, and symptoms of anxiety-related disorders among US adults. Sociology of Religion, 75(2), 208–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/srt079

Epperly, B. G. (1995). To pray or not to pray: Reflections on the intersection of prayer and medicine. Journal of Religion and Health, 34(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02248770

Exline, J. J., Wilt, J. A., Harriott, V. A., Pargament, K. I., & Hall, T. W. (2021). Is God listening to my prayers? Initial validation of a brief measure of perceived divine engagement and disengagement in response to prayer. Religions, 12(2), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12020080

Finney, J. R., & Malony, H. N. (1985). An empirical study of contemplative prayer as an adjunct to psychotherapy. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 13(4), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164718501300405

Froese, P., & Bader, C. D. (2007). God in America: Why theology is not simply the concern of philosophers. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 46(4), 465–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2007.00372.x

Froese, P., & Bader, C. (2010). America’s Four Gods: What We Say about God–and What That Says about Us. Oxford University Press.

Froese, P., & Jones, R. (2021). The sociology of prayer: Dimensions and mechanisms. Social Sciences, 10(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10010015

Froese, P., & Uecker, J. E. (2022). Prayer in America: A detailed analysis of the various dimensions of prayer. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 61(3-4), 663–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12810

Giordan, G. (2016). Spirituality. In D. Yamane (Ed.), Handbook of religion and society (Handbooks of sociology and social research (pp. 197–219). Springer.

Granqvist, P., & Kirkpatrick, L. A. (2016). Attachment and religious representations and behavior. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed., pp. 856–878). New York, NY: Guilford.

Hall, T. W., & Fujikawa, A. M. (2013). God image and the sacred. Context, theory, and researchIn K. I. Pargament, J. J. Exline, & J. W. Jones (Eds.), APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol. 1, pp. 277–292). American Psychological Association.

Hank, K., & Schaan, B. (2008). Cross-national variations in the correlation between frequency of prayer and health among older Europeans. Research on Aging, 30(1), 36–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027507307923

Henning, G. (1981). An analysis of correlates of perceived positive and negative prayer outcomes. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 9(4), 352–358.

Horwitz, A. V. (2013). Anxiety: A short history. John Hopkins University Press.

Hunter, J. D. (1990). Modern pluralism and the First Amendment: The challenge of secular humanism. The Brookings Review, 8(2), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164718100900407

James, W. (1902). The Varieties of Religious Experience. Penguin Books.

Janssen, J., De Hart, J., & Den Draak, C. (1990). A content analysis of the praying practices of Dutch youth. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 29(1), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.2307/1387033

Kent, B. V. (2020). Religion/spirituality and gender-differentiated trajectories of depressive symptoms age 13–34. Journal of Religion and Health, 59(4), 2064–2081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00958-9

Kent, B. V., & Pieper, C. M. (2019). To know and be known: An intimacy-based explanation for the gender gap in biblical literalism. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 58(1), 231–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12580

Kent, B. V., Bradshaw, M., & Uecker, J. E. (2018). Forgiveness, attachment to God, and mental health outcomes in older US adults: A longitudinal study. Research on Aging, 40(5), 456–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027517706984

Krause, N. (2004). Assessing the relationships among prayer expectancies, race, and self-esteem in late life. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 43(3), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2004.00242.x

Krause, N. (2005). God-mediated control and psychological well-being in late life. Research on Aging, 27(2), 136–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504270475

Krause, N., & Chatters, L. M. (2005). Exploring race differences in a multidimensional battery of prayer measures among older adults. Sociology of Religion, 66(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/4153114

Krause, N., & Hayward, R. D. (2013). Prayer beliefs and change in life satisfaction over time. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(2), 674–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9638-1

Krause, N., Chatters, L. M., Meltzer, T., & Morgan, D. L. (2000). Using focus groups to explore the nature of prayer in late life. Journal of Aging Studies, 14(2), 191–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-4065(00)80011-0

Levin, J. S. (1996). How prayer heals: A theoretical model. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 2(1), 66–73.

Levin, J. S. (2020). Religion and medicine. A history of the encounter between humanity’s two greatest institutions. Oxford University Press.

Levin, J. S., & Taylor, R. J. (1997). Age differences in patterns and correlates of the frequency of prayer. The Gerontologist, 37(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.1.75

Liu, Y., & Froese, P. (2020). Faith and agency: The relationships between sense of control, socioeconomic status, and beliefs about God. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 59(2), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12655

Luhrmann, T. M. (2012). When God talks back. Knopf (in press).

Luhrmann, T. M., Nusbaum, H., & Thisted, R. (2010). The absorption hypothesis: Learning to hear God in evangelical Christianity. American Anthropologist, 112(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2009.01197.x

Maltby, J., Lewis, C. A., & Day, L. (1999). Religious orientation and psychological well-being: The role of the frequency of personal prayer. British Journal of Health Psychology, 4(4), 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910799168704

Maselko, J., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2006). Gender differences in religious practices, spiritual experiences and health: Results from the US General Social Survey. Social Science & Medicine, 62(11), 2848–2860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.008

Masters, K. S., & Spielmans, G. I. (2007). Prayer and health: Review, meta-analysis, and research agenda. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30(4), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-007-9106-7

McCullough, M. E. (1995). Prayer and health: Conceptual issues, research review, and research agenda. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 23(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164719502300102

Meisenhelder, J. B., & Chandler, E. N. (2001). Frequency of prayer and functional health in Presbyterian pastors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40(2), 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/0021-8294.00059

Newberg, A., & Waldman, M. R. (2009). How God changes your brain: Breakthrough findings from a leading neuroscientist. Ballantine Books.

Olson, J. M., Roese, N. J., & Zanna, M. P. (1996). Expectancies. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 211–238). Guilford Press.

Poloma, M. M., & Gallup, G. H., Jr. (1991). Varieties of prayer: A survey report. Trinity Press International.

Rainville, G. (2018). The interrelation of prayer and worship service attendance in moderating the negative impact of life event stressors on mental well-being. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(6), 2153–2166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0494-x

Schieman, S., Bierman, A., & Ellison, C. G. (2010). Religious involvement, beliefs about God, and the sense of mattering among older adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49(3), 517–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2010.01526.x

Schnabel, L. (2015). How religious are American women and men? Gender differences and similarities. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 54(3), 616–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12214

Schnabel, L. (2018). More religious, less dogmatic: Toward a general framework for gender differences in religion. Social Science Research, 75, 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.06.010

Sharp, S. (2012). For a social psychology of prayer. Sociology Compass, 6(7), 570–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2012.00476.x

Sharp, S., Carr, D., & Panger, K. (2016). Gender, race, and the use of prayer to manage anger. Sociological Spectrum, 36(5), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2016.1198948

Spilka, B., Hood, R. W., Hunsberger, B., & Gorsuch, R. (2003). The psychology of religion: An empirical approach. Guilford Press.

Stark, R. (2017). Why God? Explaining religious phenomena. Templeton Foundation Press.

Steensland, B., Robinson, L. D., Wilcox, W. B., Park, J. Z., Regnerus, M. D., & Woodberry, R. D. (2000). The measure of American religion: Toward improving the state of the art. Social Forces, 79(1), 291–318. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/79.1.291

Watts, F. (2001). Prayer and psychology. In F. Watts (Ed.), Perspective on prayer (pp. 39–52). Chippenham: Rowe.

Whittington, B. L., & Scher, S. J. (2010). Prayer and subjective well-being: An examination of six different types of prayer. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 20(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508610903146316

Winkeljohn Black, S. W., Pössel, P., Jeppsen, B. D., Bjerg, A. C., & Wooldridge, D. T. (2015). Disclosure during private prayer as a mediator between prayer type and mental health in an adult Christian sample. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(2), 540–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9840-4

Woodhead, L. (2016). Conclusion. Prayer as changing the subject. In G. Giordan & L. Woodhead (Eds.), A sociology of prayer (pp. 213–230). Surrey, UK: Ashgate.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Upenieks, L. Unpacking the Relationship Between Prayer and Anxiety: A Consideration of Prayer Types and Expectations in the United States. J Relig Health 62, 1810–1831 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01708-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01708-0