Abstract

Recent years have witnessed increasing research interest in the collective impact of resilience, mindfulness, and self-compassion on individuals’ mental health. This longitudinal study examined the mediating effects of resilience approximately one year after the baseline assessment on baseline mindfulness, baseline self-compassion, and psychological distress approximately two years after the baseline assessment. The study involved 486 Japanese participants, surveyed at three different time points, spaced one year apart. Mediation analysis revealed two distinct pathways: (1) an indirect effect of mindfulness on psychological distress mediated by resilience, and (2) an indirect effect of self-compassion on psychological distress mediated by resilience. However, no statistically significant direct effects of mindfulness and self-compassion on psychological distress were observed. These findings suggest a fully mediated model for psychological distress with resilience serving as the mediator. The mediation model promotes mindfulness and self-compassion as practices that foster the expansion of psychological resources associated with resilience, such as attentional control and emotional regulation, ultimately leading to fewer psychological distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In today’s rapidly changing, complex, and unpredictable society, many individuals face psychological challenges that can adversely affect their psychological well-being. Thus, resilience has garnered increasing research attention as an individual difference trait that plays a pivotal role in one’s ability to bounce back from stress. One viewpoint emphasizes resilience as a personality attribute that mitigates the adverse impacts of stress and facilitates adaptation (Connor & Davidson, 2003; Wagnild & Young, 1993). A meta-analysis of sixty studies revealed that resilience is correlated with specific mental health outcomes, including depressive symptoms, anxiety, and emotions (Hu et al., 2015).

Recent years have witnessed the development of various intervention strategies to enhance resilience and promote mental health (Liu et al., 2020). Individual traits associated with different resilience levels include mindfulness, defined as intentional, in-the-moment, nonjudgmental attention (Kabat-Zinn, 1994), and self-compassion, which is the ability to embrace one’s feelings of suffering with a sense of warmth, connection, and concern (Neff, 2003; Neff & McGehee, 2010). As with resilience, both concepts are strongly associated with mental health, including depressive symptoms (e.g., Carpenter et al., 2019; MacBeth & Gumley, 2012). It is also noteworthy that mindfulness is considered a foundational component of self-compassion, which encompasses not only thoughtful, present-moment acceptance without value judgments but also a profound sense of compassion toward oneself (Neff & Dahm, 2015; Omiya & Tomita, 2021). While mindfulness and self-compassion share similar characteristics, variations in the magnitude and orientation of correlation coefficients for associated psychological factors (e.g., Phillips & Hine, 2021; Sala et al., 2020) highlight the distinctiveness of each, revealing their individual uniqueness.

Recent years have witnessed increasing research interest in the collective impact of resilience, mindfulness, and self-compassion on individuals’ mental health (e.g., Asensio-Martínez et al., 2019; Kemper et al., 2015; McArthur et al., 2017), with both mindfulness and self-compassion being examined as psychological resources contributing to resilience. For instance, a cross-sectional study involving 860 Spanish individuals, aged 18 and above, revealed the mediating role of resilience between mindfulness and self-compassion in relation to depressive symptoms (Pérez-Aranda et al., 2021). Mindfulness has also been linked to resilience through the mediating effect of self-compassion (Aydin Sünbül & Yerin Güneri, 2019). However, these mediation models have not been extensively examined across various countries and diverse populations or from a longitudinal perspective. Consequently, sufficient findings have not been amassed from a global standpoint. Ongoing validation will be necessary to ensure the replicability and generalizability of related research findings.

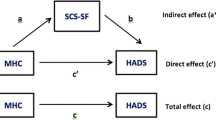

Against this context, this study aims to investigate the longitudinal relationship between mindfulness, resilience, self-compassion, and psychological distress among Japan’s general population over the course of approximately two years. The sequential relationship of the variables of mindfulness and self-compassion has been extensively discussed (e.g., Aydin Sünbül & Yerin Güneri, 2019). In this study, we take into account the uniqueness of each variable (e.g., Phillips & Hine, 2021; Sala et al., 2020) and examine two mediating pathways based on each variable. For instance, because this study seeks to establish fundamental insights for future interventions aimed at enhancing mental health and resilience, mindfulness and self-compassion were designated as independent variables, resilience as a mediating variable, and psychological distress as the outcome variable, following the methodology employed by Pérez-Aranda et al. (2021). To elucidate the mediating impact of resilience on psychological distress, the independent variables were assessed at wave 1 (baseline), the mediating variables were assessed at wave 2 (one year after the baseline assessment), and the outcome variable was evaluated at wave 3 (two years after the baseline assessment). Thus, the hypothesis of this study posits that mindfulness and self-compassion individually influence psychological distress at the two-year mark from baseline, mediated by resilience at one year. Furthermore, akin to prior research findings (Pérez-Aranda et al., 2021), the model suggests that mindfulness and self-compassion have direct effects on psychological distress.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

In October 2021, an online survey was administered to a participant pool of 4.5 million survey monitors located across Japan, registered with Freeasy – a web-based survey service offered by iBRIDGE Corporation. The survey was conducted anonymously, in accordance with iBRIDGE Corporation’s personal information processing policy. Participation was entirely voluntary. Prior to the administration of the questionnaire, the participants were informed about the aims of the study and terms of confidentiality, and their informed written consent was obtained. The survey was approved by the institutional ethics committee to which the author was affiliated (No. 21-150).

While conducting this study, a screening survey was carried out among 3,000 individuals aged 20 to 79, to exclusively select Japanese nationals. This study included 2,800 respondents who confirmed their Japanese citizenship. The sample size was capped at a maximum of 1,500 respondents, reflecting an equal distribution in terms of gender and age groups from the 20s to the 70s. Of the initial pool of 1,500 individuals who were surveyed, 1,164 participants, excluding those who violated the Directed Questions Scale (DQS; by selecting “rarely true” for this item, following the criteria established by Maniaci & Rogge, 2014), were included in the longitudinal study conducted at three time points, spaced approximately one year apart. The first time point served as the baseline for the analysis. Approximately one year after the baseline assessment, 806 individuals who participated in the study were re-assessed, with 692 individuals included, excluding those who violated the DQS. Furthermore, out of the 518 individuals who participated in the study at all three time points, 486 Japanese citizens aged 20 to 79 (242 men, 244 women; Mage = 54.8 years, SD = 14.3) who did not violate the DQS were included in the analysis. Power analyses were conducted using the pwr package (Champely, 2022) of R, version 4.3.0 (R Development Core Team, 2023). Our sample (N = 486) provided 99.9% power to detect an effect as small as r = .20 (p < .05).

Measures

Resilience

Resilience was assessed using the Adolescent Resilience Scale (Oshio et al., 2002), comprising 21 items across three dimensions: novelty seeking, emotional regulation, and positive future orientation. The reliability and validity of the ARS have been previously confirmed (Oshio et al., 2002). The participants rated the question items on a five-point scale, ranging from “definitely no” to “definitely yes.” The total score was obtained by summing the scores on each of the three dimensions, with higher scores indicating greater resilience. As resilience serves as a mediating variable in this study, we utilized the measurement data from one year after the baseline (wave 2) assessment.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness was assessed using the Japanese version of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Sugiura et al., 2012) – a translation of the original questionnaire (Baer et al., 2006). It comprises 39 items across five dimensions: observing, nonreactivity, nonjudging, describing, and acting with awareness. The reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the FFMQ have been previously confirmed (Sugiura et al., 2012). The participants rated the question items on a five-point scale, ranging from “never” to “always true.” The total score was obtained by summing the scores on each of the five dimensions, with higher scores indicating greater mindfulness. As mindfulness is considered an independent variable in this study, we utilized the measurement data from the baseline.

Self-compassion

Self-compassion was assessed using the Japanese version of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-J; Arimitsu, 2014), which is a translation of the original SCS (Neff, 2003). It comprises 26 items across six dimensions: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification. The reliability and validity of the SCS-J have been previously confirmed (Arimitsu, 2014). Participants rated the question items on a five-point scale, ranging from “almost never” to “almost always.” The total score was obtained by summing the scores on each of the six dimensions, with higher scores indicating greater self-compassion. As self-compassion is considered an independent variable in this study, we utilized the measurement data from the baseline.

Psychological Distress

Psychological distress was assessed using the Japanese version of the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (Furukawa et al., 2008), which is a translation of the original K10 (Kessler et al., 2002). The reliability and validity of the Japanese version have been previously confirmed (Furukawa et al., 2008). Participants rated the question items on a five-point scale, ranging from “none of the time” to “all of the time.” The total score was obtained by summing the scores on each of the 10 items, with higher scores indicating greater psychological distress. As psychological distress serves as the outcome variable in this study, we utilized the measurement data from two years after the baseline (wave 3).

Confounding Variables

Due to the wide age range of the population analyzed in this study, it is essential to account for variations in the impact of each variable based on its attributes. In a cross-sectional survey by Ueno et al. (2021) with 3,779 individuals aged 20 to 70, resilience correlated with sociodemographic factors like age, education level, and household income. Hence, as confounders, we used the sociodemographic factors of age, sex, education level, marital status, child status, and household income, following Ueno et al. (2021) (Table 1).

Statistical Analyses

Following the approach of Pérez-Aranda et al. (2021), we conducted a mediation analysis with mindfulness and self-compassion (at baseline) serving as independent variables, resilience (one year after baseline) as the mediating variable, and psychological distress (two years after baseline) as the outcome variable. To assess the indirect effects, the Bootstrap method was employed, with resampling of 5,000. Additionally, age, gender, education level, marital status, child status, household income, and psychological distress at baseline were included as covariates in the analysis; for this, we used structural equation modeling (SEM) with maximum likelihood estimation. Following the hypothesis of this study, we specified a correlation path between the independent variables of mindfulness and self-compassion, paths from the independent variables to the mediating variable and the outcome variable, and a model configuration with a path from the mediating variable to the outcome variable. The statistical analyses were conducted using R software, version 4.3.0 (R Development Core Team, 2023), employing packages such as psych (Revelle, 2021), lavan (Rosseel, 2012), and corrplot (Wei & Simko, 2021). The significance level for this analysis was set at 5%.

Results

Basic statistics and correlation coefficients for each variable used in this study are presented in Table 1; Fig. 1. All the correlation coefficients between psychological variables are statistically significant. A mediation analysis using SEM employed age, gender, education level, marital status, child status, household income, and psychological distress (baseline) as covariates (as illustrated in Fig. 2).

The analysis revealed positive direct effects on resilience from both mindfulness (B = 0.55, 95% CI [0.36, 0.75], B SE = 0.10, β = 0.28, p < .001) and self-compassion (B = 0.38, 95% CI [0.24, 0.52], B SE = 0.07, β = 0.30, p < .001) at wave 2. The results also demonstrated a negative direct effect from resilience on psychological distress at wave 3 (B = − 0.17, 95% CI [− 0.30, − 0.04], B SE = 0.07, β = − 0.12, p = .008), whereas mindfulness (B = − 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.26, 0.15], B SE = 0.11, β = − 0.02, p = .582) and self-compassion (B = 0.02, 95% CI [− 0.12, 0.15], B SE = 0.07, β = 0.01, p = .819) exhibited no statistically significant direct effects at wave 3.

Bootstrapping to confirm the mediation pathways of mindfulness–resilience–psychological distress and self-compassion–resilience–psychological distress and assess indirect effects yielded significant indirect effects for both mindfulness (B = − 0.10, 95% CI [− 0.18, − 0.02], B SE = 0.04, β = − 0.03, p = .017) and self-compassion (B = − 0.07, 95% CI [− 0.13, − 0.02], B SE = 0.02, β = − 0.03, p = .024), confirming a fully mediated model in which both mindfulness and self-compassion influence psychological distress through the mediating role of resilience. The mediation model employed in this study was a saturated model with zero degrees of freedom, encompassing all possible combinations of explanatory variables.

Discussion

This study sought to investigate the interplay among three critical concepts—resilience, mindfulness, and self-compassion—in relation to psychological distress in the Japanese general population. Drawing inspiration from Pérez-Aranda et al. (2021), we examined two specific pathways: first, the relationship between mindfulness (at baseline) and psychological distress (from baseline to two years later), with resilience (from baseline to one year later) serving as a mediator; second, we investigate the link between self-compassion (at baseline) and resilience (from baseline to one year later), with psychological distress (from baseline to two years later) serving as a mediator.

The findings revealed that both mindfulness and self-compassion exerted a mediating influence through resilience on psychological distress. In other words, individuals with higher levels of mindfulness and self-compassion exhibited greater resilience one year later, reflected in lower levels of psychological distress two years later. This outcome aligns with previous findings by Pérez-Aranda et al. (2021), despite variations in the measurement scales for each concept. In contrast, Pérez-Aranda et al.’s (2021) cross-sectional study identified negative direct effects of mindfulness and self-compassion on depressive symptoms in a partially mediated model, although we did not observe any direct effects in our study, indicating a fully mediated model. Although there are differences in Japanese cultural influences and the indicators by which each concept is measured, this discrepancy in results may be attributed, in part, to our prediction of psychological distress scores approximately two years later, suggesting a stronger mediating influence of resilience in this context.

Furthermore, factors such as attentional control and emotional regulation, which can be fostered through mindfulness and self-compassion practices, may contribute to cognitive changes, serving as crucial psychological resources in the development of resilience; therefore, they may be a potential mechanism linking mindfulness and self-compassion to resilience (Aydin Sünbül & Yerin Güneri, 2019; Pérez-Aranda et al., 2021; Ueno et al., 2016). The mediation model suggests that mindfulness and self-compassion foster the expansion of psychological resources associated with resilience, ultimately leading to less psychological distress. This is why many resilience intervention programs are grounded in cognitive-behavioral therapy, which targets individuals’ cognitive processes (Liu et al., 2020). Building upon previous findings, our results support the mediation model that incorporates these two concepts. Future studies should continue to investigate programs designed to mediate the impact of resilience on psychological distress and assess their effectiveness.

The limitations and challenges of this study must be addressed. Although the results revealed a mediating effect of resilience, we must exercise caution when inferring a causal relationship between each variable. To establish causality, further investigations involving, for example, psychological interventions and longitudinal experiments will be necessary. For instance, interventions designed to enhance mindfulness and self-compassion—such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (Kabat-Zinn, 1982), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (Segal et al., 2018), and the mindful self-compassion program (Neff & Germer, 2013)—could be introduced and tested. In particular, programs incorporating mindfulness and self-compassion concepts offer customized content and can be approached from various angles to enhance individual resilience. Moreover, considering the sequential relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion (Aydin Sünbül & Yerin Güneri, 2019) and aiming to clarify the mechanisms through which mindfulness and self-compassion influence resilience, it is advisable to conduct follow-up surveys and analyze the data by altering the frequency and content of measurements. Additionally, it is crucial to replicate the results of this study across diverse countries and age groups to ensure their generalizability.

Data Availability

Please contact us for any questions about the datasets.

References

Arimitsu, K. (2014). Development and validation of the Japanese version of the Self-Compassion Scale. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 85(1), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.85.50. (in Japanese with English abstract).

Asensio-Martínez, Á., Oliván-Blázquez, B., Montero-Marín, J., Masluk, B., Fueyo-Díaz, R., Gascón-Santos, S., Gudé, F., Gónzalez-Quintela, A., García-Campayo, J., & Magallón-Botaya, R. (2019). Relation of the psychological constructs of resilience, mindfulness, and self-compassion on the perception of physical and mental health. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 12, 1155–1166. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S225169.

Aydin Sünbül, Z., & Yerin Güneri, O. (2019). The relationship between mindfulness and resilience: The mediating role of self compassion and emotion regulation in a sample of underprivileged Turkish adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.12.009.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504.

Carpenter, J. K., Conroy, K., Gomez, A. F., Curren, L. C., & Hofmann, S. G. (2019). The relationship between trait mindfulness and affective symptoms: A meta-analysis of the five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Clinical Psychology Review, 74, 101785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101785.

Champely, S. (2022). pwr: Basic functions for power analysis. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pwr/pwr.pdf.

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113.

R Development Core Team (2023). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from https://www.r-project.org/.

Furukawa, T. A., Kawakami, N., Saitoh, M., Ono, Y., Nakane, Y., Nakamura, Y., Tachimori, H., Iwata, N., Uda, H., Nakane, H., Watanabe, M., Naganuma, Y., Hata, Y., Kobayashi, M., Miyake, Y., Takeshima, T., & Kikkawa, T. (2008). The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 17(3), 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.257.

Hu, T., Zhang, D., & Wang, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1490.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion.

Kemper, K. J., Mo, X., & Khayat, R. (2015). Are mindfulness and self-compassion associated with sleep and resilience in health professionals? Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(8), 496–503. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2014.0281.

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702006074.

Liu, J. J. W., Ein, N., Gervasio, J., Battaion, M., Reed, M., & Vickers, K. (2020). Comprehensive meta-analysis of resilience interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 82, 101919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101919.

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003.

Maniaci, M. R., & Rogge, R. D. (2014). Caring about carelessness: Participant inattention and its effects on research. Journal of Research in Personality, 48, 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.09.008.

McArthur, M., Mansfield, C., Matthew, S., Zaki, S., Brand, C., Andrews, J., & Hazel, S. (2017). Resilience in veterinary students and the predictive role of mindfulness and self-compassion. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 44(1), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0116-027R1.

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027.

Neff, K. D., & Dahm, K. A. (2015). Self-compassion: What it is, what it does, and how it relates to mindfulness. In B. Ostafin, M. Robinson, & B. Meier (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness and self-regulation (pp. 121–137). Springer.

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21923.

Neff, K. D., & McGehee, P. (2010). Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self and Identity, 9(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860902979307.

Omiya, S., & Tomita, T. (2021). What is mindful self-compassion? Prospects and issues. Japanese Psychological Review, 64, 388–402. https://doi.org/10.24602/sjpr.64.3_388. (In Japanese with English abstract).

Oshio, A., Nakaya, M., Kaneko, H., & Nagamine, S. (2002). Development and validation of an adolescent resilience scale. Japanese Journal of Counseling Science, 35, 57–65. (In Japanese with English abstract).

Pérez-Aranda, A., García-Campayo, J., Gude, F., Luciano, J. V., Feliu-Soler, A., González-Quintela, A., López-Del-Hoyo, Y., & Montero-Marin, J. (2021). Impact of mindfulness and self-compassion on anxiety and depression: The mediating role of resilience. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology: IJCHP, 21(2), 100229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2021.100229.

Phillips, W. J., & Hine, D. W. (2021). Self-compassion, physical health, and health behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 15(1), 113–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2019.1705872.

Revelle, W. (2021). psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research. Retrieved July 18, 2021, from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psych/psych.pdf.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

Sala, M., Rochefort, C., Lui, P. P., & Baldwin, A. S. (2020). Trait mindfulness and health behaviours: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 14(3), 345–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2019.1650290.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, M., Teasdale, J., Kabat-Zinn, J., & Clark, D. M. (2018). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Sugiura, Y., Sato, A., Ito, Y., & Murakami, H. (2012). Development and validation of the Japanese version of the five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. Mindfulness, 3(2), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0082-1.

Ueno, Y., Iimura, S., Amemiya, R., & Kase, T. (2016). An approach to both recovery and growth following difficult situations: The perspective of resilience, posttraumatic growth, and mindfulness. Japanese Psychological Review, 59, 388–402. https://doi.org/10.24602/sjpr.59.4_397. (In Japanese with English abstract).

Ueno, Y., Hirano, M., & Oshio, A. (2021). Resilience and socio-demographic characteristics: Results from a large cross-sectional study in Japan. Asian Pacific Journal of Disease Management, 10(1–2), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.7223/apjdm.10.25.

Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1(2), 165–178.

Wei, T., & Simko, V. (2021). corrplot: Visualization of a correlation matrix. Retrieved December 30, 2022, from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/corrplot/index.html.

Acknowledgements

We used DeepL, Grammarly, and ChatGPT for English proofreading. Additionally, we would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English-language editing.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI 21K13689.

Open Access funding provided by The University of Tokyo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ueno, Y., Amemiya, R. Mediating Effects of Resilience Between Mindfulness, Self-compassion, and Psychological Distress in a Longitudinal Study. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-024-00553-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-024-00553-2