Abstract

This systematic review and meta-analysis explores the effectiveness of teacher interventions supporting children with externalizing behaviors based on teacher and child outcomes. A systematic search was conducted using 5 electronic databases. From 5714 papers, 31 papers that included interventions delivered directly to teachers and aimed to benefit either teachers and/or children with externalizing behaviors were included. The review focused on qualified teachers working with children aged 2–13. The results of the current meta-analysis revealed a positive effect of teacher intervention on teacher and child outcomes, including the increased use of teacher-appropriate strategies, as well as significant and moderate improvements in teacher–child closeness, and small reductions in teacher–child conflict. For child outcomes, the interventions reduced externalizing behavior problems and ADHD symptoms and enhanced prosocial behavior. Only one fully blinded analysis for conduct problems was possible and revealed a moderate but significant reduction in favor of intervention. These findings provide evidence to support the role of teacher interventions for both teachers and children with externalizing behaviors. Future research should include more PBLIND measurements so that MPROX findings can be confirmed. More research should be done to evaluate the influence of teacher interventions on teachers’ well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Externalizing behaviors, including conduct problems and the symptoms associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), account for about 7% of school-based problems in childhood (Polanczyk et al., 2014). Children with externalizing behaviors can be challenging to teach because they display higher levels of developmentally inappropriate behaviors like hyperactivity, inattention, disobedience, impulsivity, and tantrums (Doepfner et al., 2004). Children who exhibit externalizing behaviors are often a focus of classroom disruption (Daley et al., 2014) and also experience disrupted peer relationships (Lewis et al., 2016). Teachers’ well-being can also be influenced by the impact of children’s externalizing behaviors on classroom management (Brill & McCartney, 2008), which highlights both the direct and indirect impact of these behaviors.

Externalizing behaviors in children are often associated with greater levels of peer rejection and more difficulty with friendship formation (Rubin et al., 2018), as well as challenges with teamwork, peer interaction, and sharing (Ettekal & Ladd, 2014). Children who engage in externalizing behaviors often struggle to interact with teachers (Williford et al., 2017); fail to follow appropriate teacher instructions or complete work on time (DuPaul & Stoner, 2014). They also display frequent tantrums and/or outbursts (Dupaul et al., 2001). Consequently, implementing educational programming with children who display externalizing behavior is a challenging task for teachers (Williford & Shelton, 2014).

Providing teachers with appropriate behavioral strategies to help manage externalizing behaviors more effectively is vital for the children themselves, as well as overall classroom management (Daley et al., 2014), and teachers’ well-being (Aloe et al., 2014). Previous research studies have shown that parenting interventions that help parents to modify the home environment can reduce children’s level of externalizing behaviors at home and enhance social development (Webster-Stratton, 2011). Buchanan-Pascall et al. (2018) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis that investigated the efficacy of parent-mediated intervention for children with externalizing behaviors and concluded that 80% of studies confirmed the efficacy of parent-mediated interventions, thus supporting the parent’s role in reducing externalizing behaviors (Buchanan-Pascall et al., 2018). However, although numerous studies and meta-analyses have explored parent-mediated interventions, there is little research on teacher-mediated interventions despite evidence that shows the impact of externalizing behaviors on teachers’ well-being (Aloe et al., 2014) and self-efficacy (Collie et al., 2012); both of which can have an immediate impact on children in the classroom (Miller et al., 2017).

Teachers often struggle to manage children with externalizing behavior (Herman et al., 2017) and classroom disruption can interfere with the teaching process (Savage et al., 2017). For example, Arbuckle and Little (2004) asked 96 teachers to report the types of challenging behavior experienced by teachers and their confidence in utilizing behavior management strategies in the classroom; their findings showed that child aggression and hyperactivity were teachers’ greatest concerns. Arbuckle and Little also found an association between lower teacher confidence and higher levels of hyperactivity and non-compliance in male students. Arbuckle and Little’s findings are consistent with other studies that have shown that lower teacher confidence levels are associated with higher levels of difficulty in terms of teachers’ ability to teach and manage difficult students (Stephenson et al., 2000).

Difficult-to-manage student behavior in the classroom can also impact the teacher–child relationship (TCR). Daley et al., (2005) and McGrath and Van Bergen (2017) both explored TCR using measures of expressed emotion (EE) to gauge warmth and criticism expressed by teachers toward children with externalizing behavior. Both studies found that teachers directed higher levels of criticism and lower levels of warmth toward students who displayed externalizing behaviors than to matched controls. These studies focused exclusively on the impact that disruptive pupils may have on TCR (Daley et al., 2005; McGrath & Van Bergen, 2017). Since parental EE has also been shown to correlate with negative parent–child interaction (Daley et al., 2005; Tompson et al., 2015), it is plausible that teacher EE may also be a proxy marker for teacher–pupil interaction. Therefore, higher teacher warmth and lower teacher criticism may help to reduce the expression of externalizing behaviors in the classroom, although this has not yet been empirically examined. The current systematic review and meta-analysis therefore aims to explore the effectiveness of teacher-delivered interventions in supporting children who display externalizing behaviors based on child and teacher outcomes.

Methods

Search Strategy

The researchers conducted the search on February 5, 2018, and it was refreshed on September 27, 2018, April 19, 2020, and July 16, 2021, using the following electronic databases: Ovid (Embase 1974-present, MEDLINE 1980-present, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES), and Web of Science database. To make the search more comprehensive, the researchers conducted backward and forward citation searching using Google Scholar (Higgins et al., 2019; Polanin & Pigott, 2015). See PROSPERO registered protocol number (CRD42018095476) for more details.

Inclusion Criteria

The authors limited the scope of the published trials based on Cochrane group recommendations (Higgins et al., 2019). The current meta-analysis included only peer-reviewed, randomized control trials (RCTs) published in English and focused on externalizing behaviors in childhood. The current systematic review and meta-analysis focused on qualified teachers working with children aged 2–13 years and studies that measured teacher outcomes and/or child problem behavior. The current analysis included children who exhibited high levels of externalizing behaviors (ADHD symptoms or conduct problems) based on teacher reports. All studies had to include behavioral interventions delivered specifically to teachers and aimed to benefit either teachers and/or children with externalizing behaviors. The authors excluded studies that measured only teachers’ knowledge; comparison control conditions could include waiting lists, treatment as usual, or alternative treatment, while trials could include either child and/or teacher outcomes. The researchers also excluded studies that included individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) since the intention was to focus on externalizing behaviors and individuals displaying high levels of symptoms of behavioral disorders (e.g., ADHD; oppositional defiant disorder [ODD]; conduct disorder).

Study Selection

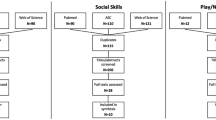

The PRISMA protocol (Moher et al., 2009) informed the current systematic review and meta-analysis. Figure 1 shows a flowchart describing the process for study selection; the retrieved references were screened by title and abstract independently and blindly double-coded for eligibility. The authors resolved any disagreements between them and reviewed full-text articles for eligibility (see Fig. 1).

Thirty-one studies met the inclusion criteria, but only 22 of them contributed to the meta-analysis as nine studies did not provide data that could be used in the meta-analysis (see Table 1); nevertheless, the authors included them in the systematic review by describing the interventions and identifying the study characteristics, as shown in Tables 2 and 3. Some of the included studies employed the same sample size yet produced different outcomes. The authors accounted for this when computing the total number of students and teachers to avoid doubling the figures.

Data Extraction and Statistical Analysis

Both authors performed data extraction at an independent level and agreed on the data extraction. The standardized mean difference (SMD) represented the mean change pre-to-post-treatment for the intervention arm minus the mean change pre-to-post-treatment for the control arm divided by the pooled pre-test standard deviation with a bias adjustment. The researchers performed the calculations using the Review Manager (RevMan) computer program, Version5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration group (Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). This paper used the Inverse-Variance IV method and a random-effects model due to the integral heterogeneity of studies, calculating the I2 statistics, a posteriori, to give an estimation of between-trial SMD heterogeneity (Field & Gillett, 2010).

Coding Procedure

The first author coded all the data and the last author verified the coding. The study codes consisted of (a) children’s selection method and by whom, (b) study design, (c) type of control condition, (d) number of participants (whether they were teachers, children, or both in intervention and control arm), (e) age of children, (f) teachers’ years of experience, (g) female percentage for teachers, (h) male percentage for children (see Table 4). The intervention data coding included a description of the intervention, including type, duration, and geographic location (see Table 5).

Statistical data included mean standard deviation and the number of participants in both arms. Eleven studies had a lack of sufficient information (e.g., blinding) and statistical information (e.g., standard deviation, mean), so the first author contacted the corresponding authors. The authors of four of these studies emailed this paper’s researchers with the missing data within the agreed time window (i.e., three reminders). In some cases, this paper estimated missing data using the method described by Hozo et al. (2005) to calculate the mean and estimate the standard deviation (Wan et al., 2014). Missing data for three studies meant that it was impossible to obtain or calculate an effect size; these studies were included in the review but excluded from the meta-analysis.

Methodological Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (RD and DD) conducted the quality assessment by evaluating the quality of data in the included studies, using the Cochrane group Risk of Bias-2 (RoB-2) to assess the overall quality of the included RCTs (Higgins et al., 2011). Agreement between the two authors was 90% and any disagreements were resolved between the authors without the need for a third party. A high percentage of studies introduced some theoretical risk of selection bias since the nature of studies that included teachers and their students lacked blinding. However, adequate randomization across all studies meant that the overall risk of selection bias was low, while an adequate description of the study results reduced reporting bias across all studies. Unfortunately, the lack of a double-blinded approach in most studies introduced a higher risk of performance bias. The overall and study-level bias of the included RCTs is reported in Fig. 2.

Outcomes Coding

The current analysis aimed to increase analytical robustness by considering outcome domains that included at least five studies, as recommended by Daley et al. (2014), Faraone et al. (2021), Higgins et al. (2019), Sonuga-Barke et al. (2013). The authors considered different perspectives, including the most proximal view (MPROX), which represents the view of the person closest to the receipt of treatment, or the probably blinded view of a person unaware of treatment allocation (PBLIND) (Daley et al., 2014; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2013). In the present study, PBLIND outcomes were only available for conduct problems. The researchers categorized outcomes as teacher-focused or child-focused outcomes.

Measures for Teacher-Focused Outcomes

There were three outcomes for teachers: warmth and closeness, teacher–child conflict, and teachers’ use of positive strategies. Other than one study that measured warmth using the Teacher–Pupil Observation Tool (TPOT), all studies in the warmth/closeness domain used the same measure, Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS). All of the studies that comprised the teacher–child conflict outcome were based on a single measure, STRS. The studies for the outcome of teachers’ use of positive strategies were heterogeneous and included papers that used different measures for teachers’ positive behavior, such as classroom management, general praise, responsive behavior, and classroom instructional support. The teacher well-being outcome was not included because there were insufficient included studies to measure it.

Measures for Child-Focused Outcomes

This outcome had four domains, externalizing problems, prosocial behaviors, ADHD symptoms, and conduct problems. The externalizing behavior problems domain was heterogeneous and comprised studies that measured oppositional behavior, challenging behavior, and conduct behavior, using a variety of measures as listed in Table 4. For prosocial behavior, the included studies measured peer relationships, prosocial skills, and social behavior using a range of measures as listed in Table 4. For ADHD outcome behavior, the researchers grouped hyperactivity symptoms and inattention symptoms together for some studies if they were listed separately. The included studies in this domain used Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) and Conners Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS) measures. Finally, the conduct problem PBLIND outcome used observational measures to assess aggression and conduct problems. See Table 4 for more information about the measures.

Analysis

The researchers conducted the current analysis using a random-effects model by measuring the standard mean difference (SDM) between the intervention and control groups. Results of the meta-analysis for each teacher and child outcome are reported in Table 3.

Results

Teacher Outcomes

Six studies provided measures of teachers’ closeness toward the child. All were MPROX except for Baker-Henningham (b) (Baker-Henningham et al., 2009b). The present analysis revealed a moderate but significant result concerning the impact of interventions on teacher–child closeness. Heterogeneity among the included studies was large and significant. The SDM in this analysis was influenced by Baker-Henningham (b) who reported an SMD of 2.42. Sensitivity analysis removing this study still provided a small but significant result in favor of intervention (SMD of 0.29) and 0% heterogeneity because the remaining studies all used the same instrument (see Fig. 3). Heterogeneity is the clinical variability within the various samples, methodological variability across the various included studies, and statistical variability among the included studies in an outcome.

Five studies provided measures of teacher–child conflict based on teacher ratings, all of which were MPROX. The current analysis revealed a small but significant result of intervention on teacher–child conflict. Heterogeneity among the included studies was not significant as all the studies used the same measure (see Fig. 4).

Eight studies explored teachers’ use of appropriate strategies. All observational measures except for Downer et al. (2018) consisted of rating scales. Four studies (Baker-Henningham & Walker, 2018; Conroy et al., 2015; Downer et al., 2018; Sutherland et al., 2020) were MPROX and the other four (Hickey et al., 2017; Hoogendijk et al., 2020; Reinke et al., 2014; Stoiber & Gettinger, 2011) were PBLIND. There was an insufficient number of blinded studies that represent the view of the person closest to the person unaware of treatment allocation to conduct a separate PBLIND outcome. Heterogeneity among the included studies was large and significant (see Fig. 5).

Child Outcomes

Thirteen studies included measures of child’s externalizing behavior. All of them were teacher-rated, and MPROX except for Conroy study that used an observational measure (Conroy et al., 2015). The current analysis revealed a moderate but significant impact of intervention on reducing externalizing behavior. Heterogeneity in the analysis was small but significant (Fig. 6).

Five studies provided PBLIND measures of child conduct problems in the form of observational measures. The current analysis revealed a large and significant impact of interventions on child conduct problems. There was, however, considerable heterogeneity, which was significant. The SDM in this analysis was influenced by Stoiber’s study (Stoiber & Gettinger, 2011), who reported an SMD of 1.15. Sensitivity analysis removing this study still provided a small but significant SMD of 0.21 (see Fig. 7).

Nine studies provided measures of child prosocial behavior, eight of which provided teacher ratings, all of which were MPROX, while one study provided blinded observational scores (Hutchings et al., 2013). There was a moderate but significant result of the impact of interventions on prosocial behavior and heterogeneity was low and nonsignificant (see Fig. 8).

Six studies provided measures of child ADHD combined symptoms, all of which were MPROX and teacher-rated. The results indicated a moderate but significant impact of the intervention on ADHD symptoms in children. Heterogeneity was 0% in the analysis, perhaps since the majority of the studies used the same measure (see Fig. 9).

Discussion

The current meta-analysis of RCTs investigated the efficacy of providing teacher support for children with externalizing problems, based on both teacher and child-focused outcomes. In total, 22 studies contributed to the meta-analysis, which included 861 teachers and 1841 children across intervention and control arms. Where possible, the results were reviewed by examining two different viewpoints including the MPROX and a PBLIND (Daley et al., 2014; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2013). Due to the variability of intervention targets, children’s ages, and outcomes, considerable heterogeneity was evident in the meta-analysis except where the same measures were used in all or most studies.

Both teacher and child outcomes were included in the current analysis, which found significant and moderate teacher-mediated intervention-related improvements for teacher–child closeness. Teacher use of appropriate strategies was a mixture of MPROX (provided by individuals who are aware of intervention allocation) and PBLIND outcomes (provided by individuals who are unaware of intervention allocation based on questionnaires and observations provided by individuals). The results found large and significant improvements in favor of intervention for teachers’ use of classroom management strategies, providing general praise to students, and utilizing responsive behavior in the classroom, in contrast to the smaller but significant results for the intervention that led to reduced conflict between teachers and children with externalizing behavior. Taken together, these findings support the positive impact of interventions on teachers’ skills development and relationships with children, although the results for teacher outcomes lacked confirmation from blinded outcomes.

The current meta-analysis also highlighted intervention-related improvement in child behavior problems. In particular, the results revealed a moderate but significant reduction in externalizing behavior problems and ADHD symptoms in children. Moreover, the results also found a moderate and significant increase in children’s prosocial behavior as a result of teacher-mediated intervention in the included studies.

Blinded evidence for the efficacy of teacher-mediated interventions was explored in the current analysis on child conduct problems using outcomes provided by individuals who are unaware of intervention allocation. This outcome was the only blinded analysis in the current meta-analysis and confirmed the impact of interventions on blinded teacher reports of child conduct behavior. This finding highlights the need for more blinded outcomes to further explore and test the effectiveness of teachers’ interventions beyond unblinded teacher ratings, in line with recommendations by Daley et al. (2014).

Results from the current meta-analysis suggest that teacher-mediated interventions demonstrated an improvement in conduct problems using PBLIND measures. Significant improvements were also demonstrated by MPROX measures for children’s ADHD-related symptoms and prosocial behavior. These results are in line with the results of Daley et al. (2014), which reported significant MPROX and PBLIND improvements in conduct problems; but only MPROX improvements in ADHD-related symptoms for parent-mediated interventions for children with ADHD.

Another meta-analysis (Iznardo et al., 2020) was conducted to examine the effectiveness of more focused daily report cards interventions in reducing ADHD symptoms rated by teachers also reported a reduction in conduct problems for children with ADHD using MPROX (rating scales) and PBLIND (observational measures). In fact, the PBLIND outcomes were found to be more sensitive in measuring ADHD symptom change compared to rating scales although this meta-analytic study included non-RCTs and there were less than five studies in the PBLIND analysis (Iznardo et al., 2020).

The current meta-analysis also found a significant reduction in conduct problems and ADHD symptoms with larger effect sizes than a previous meta-analysis from Stoltz et al. (2012). Stoltz et al. investigated the efficacy of school-based interventions on school-aged children with externalizing behavior from two different perspectives. The first was solely child-focused interventions. The second included other intervention targets in addition to a focus on the child, such as modifying the school environment and direct parent support. Both perspectives (the child-focused-only intervention and the intervention that included both child and other elements) demonstrated a reduction in externalizing behavior with SMD 0.30 and 95% CI = 0.14 − 0.46 for child-focused intervention and SMD 0.30 and 95% CI = 0.04 − 0.56 for the child-focused and other components intervention (Stoltz et al., 2012).

ADHD symptoms in particular can negatively impact the teacher–student relationship (Rogers et al., 2016). Enhancing warmth and closeness may be potentially beneficial to children, as Wang et al. (2016) demonstrated in their study using measures of closeness and conflict. The study revealed that children whose emotional relationship with their teachers was high in closeness and low in conflict had better peer relationships and fewer emotional/internalizing problems (Wang et al., 2016). In contrast, the results of the present meta-analysis demonstrated a small but significant enhancement in closeness and reduction of conflict in favor of intervention. These improvements may have an additional impact on children’s outcomes beyond what could be identified in the current analysis.

The current results highlight that little is known about the impact of teacher-mediated interventions on teachers’ self-efficacy and well-being. The number of studies that measured teachers’ stress levels or self-efficacy in the current analysis was insufficient to draw conclusions about these dependent variables. This was surprising and highlights a gap in the current literature since several studies have demonstrated the relationship between children’s level of externalizing behaviors and teachers’ level of confidence in classroom management (Arbuckle & Little, 2004; Collie et al., 2012; Stephenson et al., 2000). School responsibilities and workload can also cause stress and negative emotions in teachers (Fernet et al., 2012; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011). Liu and Onwuegbuzie (2012) also found that disruptive behavior in the classroom is one of the primary causes of teachers’ stress (Liu & Onwuegbuzie, 2012). Therefore, future studies should investigate the impact of teacher-mediated interventions on teacher stress and self-efficacy in greater detail. The aim would be to either confirm that current interventions also target teacher well-being, or potentially highlight the need for specific interventions that target these important outcomes.

The interventions included in the current meta-analysis were predominantly delivered face to face and only two online interventions were included in the review. Given the considerable work-related pressure that teachers encounter and the financial limitations they experience when taking time away from the classroom to enhance their skill set, this finding was also surprising. Future research should expand the evaluation of digital interventions for teachers to widen participation and reduce barriers to engagement, especially considering the additional limitations that have been imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first meta-analysis of teacher-mediated interventions for children with externalizing behaviors. The current analysis focused on peer-reviewed RCTs only and involved a systematic search conducted across five databases. Moreover, the current analysis focused on two different sets of outcomes including teacher and child, as well as two levels of reporting, MPROX and PBLIND. The outcomes were informed by the recommended number of studies necessary in a meta-analysis (Daley et al., 2014; Faraone et al., 2021; Higgins et al., 2019; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2013). However, this meta-analysis was limited by the lack of data on teachers’ outcomes in the included studies and the inability to confirm any of the teacher outcomes using PBLIND measures.

A second limitation was that an investigation of the long-term impact of teacher intervention was not possible due to the lack of sufficient data since many studies did not include long-term follow-up data, meaning that the long-term extent of behavior change remains unclear. A third limitation was that the total number of teachers involved could not be precisely measured because some studies that focused primarily on child outcomes did not indicate the number of teachers involved in the study. Fourth, we included studies in the ADHD outcome if they had an ADHD symptoms result, but we are unaware of comorbidity.

Fifth, it was difficult to explore publication bias because this review only included published papers. However, the authors generated and inspected funnel plots in line with recommendations from the Cochrane group (Higgins et al., 2019), and restricted the interpretation of funnel plots for outcomes with 10 or more studies and where there was heterogeneity in measures only; all of which made it impossible to comment on publication bias within the current analysis.

Sixth, while some scholars recommend the inclusion of unpublished studies in meta-analyses; the restriction of the analysis to published studies was to ensure greater methodological rigor in the analysis and enhance the validity of the findings and recommendations. Finally, the present study calculated the effect sizes using shifting units of analysis, as is standard practice within the Cochrane group (Higgins et al., 2019). However, this method can increase the number of statistical tests run (Pigott & Polanin, 2020). Using a different approach such as robust variance estimation or multi-level modeling can adjust the effect size and increase independency (Tipton et al., 2019; Van den Noortgate et al., 2015) although it was not suitable for this particular analysis.

This meta-analysis, focusing on both teacher and child outcomes, aimed to explore the potential of interventions for supporting teachers of children with externalizing problems in school. The results of this study indicate that addressing externalizing problems in children using teacher-mediated intervention was beneficial for both teachers and children. Moreover, the current results suggest that future research should examine the impact of teacher-mediated interventions on teachers’ well-being and self-efficacy. It would also be important in the future for trials to include more PBLIND measures so that current MPROX findings could be confirmed using PBLIND outcomes.

Data Availability

Data can be obtained from the first author following completion of her PhD.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

Aloe, A. M., Shisler, S. M., Norris, B., Nickerson, A., & Rinker, T. (2014). A multivariate meta-analysis of student misbehavior and teacher burnout. Educational Research Review, 12, 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.05.003

Arbuckle, C., & Little, E. (2004). Teachers’ perceptions and management of disruptive classroom behaviour during the middle years (years five to nine). Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 4, 59–70.

Baker-Henningham, H., & Walker, S. (2018). Effect of transporting an evidence-based, violence prevention intervention to Jamaican preschools on teacher and class-wide child behaviour: A cluster randomised trial. Global Mental Health, 5, e7. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2017.29

Baker-Henningham, H., Walker, S., Powell, C., & Gardner, J. M. (2009a). A pilot study of the incredible years teacher training programme and a curriculum unit on social and emotional skills in community pre-schools in Jamaica. Child Care Health and Development, 35(5), 624–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00964.x

Baker-Henningham, H., Walker, S., Powell, C., & Gardner, J. M. (2009b). Preventing behaviour problems through a universal intervention in Jamaican basic schools: A pilot study. West Indian Medical Journal, 58(5), 460–464.

Baker-Henningham, H., Scott, S., Jones, K., & Walker, S. (2012). Reducing child conduct problems and promoting social skills in a middle-income country: Cluster randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 201, 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096834

Behar, L. B. (1977). The preschool behavior questionnaire. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 5(3), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00913697

Bloomquist, M. L., August, G. J., & Ostrander, R. (1991). Effects of a school-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for ADHD children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 19(5), 591–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00925822

Brill, S., & McCartney, A. (2008). Stopping the revolving door: Increasing teacher retention. Politics & Policy, 36(5), 750–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1346.2008.00133.x

Buchanan-Pascall, S., Gray, K. M., Gordon, M., & Melvin, G. A. (2018). Systematic review and meta-analysis of parent group interventions for primary school children aged 4–12 years with externalizing and/or internalizing problems. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 49(2), 244–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-017-0745-9

Caldarella, P., Larsen, R., Williams, L., Wills, H., Kamps, D., & Wehby, J. (2018). Effects of CW-FIT on teachers ratings of elementary school students at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(2), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717723353

Chandler, L. K., Dahlquist, C. M., Repp, A. C., & Feltz, C. (1999). The effects of team-based functional assessment on the behavior of students in classroom settings. Exceptional Children, 66(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440299906600107

Cochrane Collaboration. (2014). Review manager (RevMan) version 5.2. The Nordic Cochrane Centre.

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 1189–1204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029356

Conroy, M. A., Sutherland, K. S., Algina, J., Ladwig, C., Werch, B., Martinez, J., Jessee, G., & Gyure, M. (2019). Outcomes of the best in class intervention on teachers’ use of effective practices, self-efficacy, and classroom quality. School Psychology Review, 48(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2018-0003.V48-1

Conroy, M. A., Sutherland, K. S., Algina, J., Werch, B., & Ladwig, C. (2018). Prevention and treatment of problem behaviors in young children: Clinical implications from a randomized controlled trial of BEST in CLASS. AERA Open, 4(1), 2332858417750376. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858417750376

Conroy, M. A., Sutherland, K. S., Algina, J. J., Wilson, R. E., Martinez, J. R., & Whalon, K. J. (2015). Measuring teacher implementation of the BEST in CLASS intervention program and corollary child outcomes. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 23(3), 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426614532949

Conroy, M. A., Sutherland, K. S., Granger, K. L., Marcoulides, K. M., Huang, K., & Montesion, A. (2021). Preliminary study of the effects of BEST in CLASS—web on young children’s social-emotional and behavioral outcomes. Journal of Early Intervention, 44(1), 78–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/10538151211018662

Corkum, P., Elik, N., Blotnicky-Gallant, P. A. C., McGonnell, M., & McGrath, P. (2019). Web-based intervention for teachers of elementary students with ADHD: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(3), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054715603198

Daley, D., Renyard, L., & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S. (2005). Teachers’ emotional expression about disruptive boys. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709904X22269

Daley, D., van der Oord, S., Ferrin, M., Danckaerts, M., Doepfner, M., Cortese, S., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2014). Behavioral interventions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials across multiple outcome domains. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(8), 835–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.05.013

Doepfner, M., Rothenberger, A., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2004). Areas for future investment in the field of ADHD: Preschoolers and clinical networks. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 13, I130–I135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-004-1012-8

Downer, J. T., Williford, A. P., Bulotsky-Shearer, R. J., Vitiello, V. E., Bouza, J., Reilly, S., & Lhospital, A. (2018). Using data-driven, video-based early childhood consultation with teachers to reduce children’s challenging behaviors and improve engagement in preschool classrooms. School Mental Health, 10(3), 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9237-0

Dupaul, G., Mcgoey, K., Eckert, T., & Vanbrakle, J. (2001). Preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Impairments in behavioral, social, and school functioning. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(5), 508–515. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200105000-00009

DuPaul, G. J., & Stoner, G. (2014). ADHD in the schools: Assessment and intervention strategies (3rd ed.). Guilford Publications.

Ettekal, I., & Ladd, G. W. (2014). Developmental pathways from childhood aggression-disruptiveness, chronic peer rejection, and deviant friendships to early-adolescent rule breaking. Child Development, 86(2), 614–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12321

Eyberg, S. M. (1999). Eyberg child behavior inventory and Sutter-Eyberg student behavior inventory-revised: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

Eyberg, S. M., & Robinson, E. A. (1981). Dyadic parent–child interaction coding system. Parenting Clinic, University of Washington.

Faraone, S. V., Banaschewski, T., Coghill, D., Zheng, Y., Biederman, J., Bellgrove, M. A., Newcorn, J. H., Gignac, M., Al Saud, N. M., & Manor, I. (2021). The world federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 128, 789–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.022

Fernet, C., Guay, F., Senécal, C., & Austin, S. (2012). Predicting intraindividual changes in teacher burnout: The role of perceived school environment and motivational factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(4), 514–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.013

Field, A. P., & Gillett, R. (2010). How to do a meta-analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 63(3), 665–694. https://doi.org/10.1348/000711010X502733

Gonzales-Ball, T., & Bratton, S. (2019). Child–teacher relationship training as a head start early mental health intervention for children exhibiting disruptive behavior. International Journal of Play Therapy, 28(1), 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/pla0000081

Goodman, A., & Goodman, R. (2009). Strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(4), 400–403. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181985068

Goyette, C. H., Conners, C. K., & Ulrich, R. F. (1978). Normative data on revised Conners parent and teacher rating scales. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 6(2), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00919127

Gresham, F., & Elliott, S. N. (2007). Social skills improvement system (SSIS) rating scales. Pearson Education Inc.

Herman, K., Hickmon-Rosa, J., & Reinke, W. (2017). Empirically derived profiles of teacher stress, burnout, self-efficacy, and coping and associated student outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(2), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717732066

Hickey, G., McGilloway, S., Hyland, L., Leckey, Y., Kelly, P., Bywater, T., Comiskey, C., Lodge, A., Donnelly, M., & O’Neill, D. (2017). Exploring the effects of a universal classroom management training programme on teacher and child behaviour: A group randomised controlled trial and cost analysis. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 15(2), 174–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718x15579747

Higgins, J. P., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley.

Higgins, J. P., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., Savović, J., Schulz, K. F., Weeks, L., & Sterne, J. A. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343, d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

Hoogendijk, C., Tick, N., Holland, J., Hofman, W., Severiens, S., Vuijk, P., & van Veen, A. (2020). Effects of Key2Teach on students’ externalising and social-emotional problem behaviours, mediated by the teacher–student relationship. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 25(3–4), 304–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2020.1858259

Hoogendijk, C., Tick, N. T., Hofman, W. H. A., Holland, J. G., Severiens, S. E., Vuijk, P., & van Veen, A. (2018). Direct and indirect effects of Key2Teach on teachers’ sense of self-efficacy and emotional exhaustion, a randomized controlled trial. Teaching and Teacher Education, 76, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.07.014

Hozo, S. P., Djulbegovic, B., & Hozo, I. (2005). Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 5(1), 1–10.

Hutchings, J., Martin-Forbes, P., Daley, D., & Williams, M. E. (2013). A randomized controlled trial of the impact of a teacher classroom management program on the classroom behavior of children with and without behavior problems. Journal of School Psychology, 51(5), 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.08.001

Iznardo, M., Rogers, M. A., Volpe, R. J., Labelle, P. R., & Robaey, P. (2020). The effectiveness of daily behavior report cards for children with ADHD: A meta-analysis. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(12), 1623–1636. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717734646

Koth, C. W., Bradshaw, C. P., & Leaf, P. J. (2009). Teacher observation of classroom adaptation—checklist: Development and factor structure. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 42(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175609333560

Lewis, G. J., Asbury, K., & Plomin, R. (2016). Externalizing problems in childhood and adolescence predict subsequent educational achievement but for different genetic and environmental reasons. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(3), 292–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12655

Liu, S., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2012). Chinese teachers’ work stress and their turnover intention. International Journal of Educational Research, 53, 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.03.006

LoCasale-Crouch, J., Williford, A., Whittaker, J., DeCoster, J., & Alamos, P. (2018). Does fidelity of implementation account for changes in teacher-child interactions in a randomized controlled trial of banking time? Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 11(1), 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2017.1329365

Martin, P., Daley, D., Hutchings, J., Jones, K., Eames, C., & Whitaker, C. (2010). The teacher-pupil observation tool (T-POT) development and testing of a New classroom observation measure. School Psychology International, 31(3), 229–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034310362040

McCullough, S. N., Granger, K. L., Sutherland, K. S., Conroy, M. A., & Pandey, T. (2021). A preliminary study of BEST in CLASS–elementary on teacher self-efficacy, burnout, and attributions. Behavioral Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1177/01987429211010672

McGrath, K. F., & Van Bergen, P. (2017). Elementary teachers’ emotional and relational expressions when speaking about disruptive and well behaved students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.07.016

Merrell, K. W., & Gimpel, G. (1998). Social skills of children and adolescents: Conceptualization, assessment, treatment. Psychology Press.

Miller, A. D., Ramirez, E. M., & Murdock, T. B. (2017). The influence of teachers’ self-efficacy on perceptions: Perceived teacher competence and respect and student effort and achievement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 64, 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.008

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., PRISMA Group*. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269.

Owens, J. S., Coles, E. K., Evans, S. W., Himawan, L. K., Girio-Herrera, E., Holdaway, A. S., Zoromski, A. K., Schamberg, T., & Schulte, A. C. (2017). Using multi-component consultation to increase the integrity with which teachers implement behavioral classroom interventions: A pilot study. School Mental Health, 9(3), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9217-4

Pianta, R. C. (2001). Student–teacher relationship scale. Psychological Assessment Resources.

Pigott, T. D., & Polanin, J. R. (2020). Methodological guidance paper: High-quality meta-analysis in a systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 90(1), 24–46. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319877153

Polanczyk, G. V., Willcutt, E. G., Salum, G. A., Kieling, C., & Rohde, L. A. (2014). ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 434–442. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt261

Polanin, J. R., & Pigott, T. D. (2015). The use of meta-analytic statistical significance testing. Research Synthesis Methods, 6(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1124

Rayfield, A., Eyberg, S. M., & Foote, R. (1998). Revision of the Sutter-Eyberg student behavior inventory: Teacher ratings of conduct problem behavior. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 58(1), 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164498058001008

Reinke, W., Stormont, M., Herman, K., Wang, Z., Newcomer, L., & King, K. (2014). Use of coaching and behavior support planning for students with disruptive behavior within a universal classroom management program. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 22(2), 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426613519820

Rogers, S., Barblett, L., & Robinson, K. (2016). Investigating the impact of NAPLAN on student, parent and teacher emotional distress in independent schools. The Australian Educational Researcher, 43, 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-016-0203-x

Rubin, K. H., Laursen, B., & Bukowski, W. M. (2018). Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Savage, J., Ferguson, C. J., & Flores, L. (2017). The effect of academic achievement on aggression and violent behavior: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 37, 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.08.002

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(6), 1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.04.001

Sonuga-Barke, E. J., Brandeis, D., Cortese, S., Daley, D., Ferrin, M., Holtmann, M., Stevenson, J., Danckaerts, M., Van der Oord, S., & Döpfner, M. (2013). Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070991

Spilt, J., Koomen, H., Thijs, J., & van der Leij, A. (2012). Supporting teachers relationships with disruptive children: The potential of relationship-focused reflection. Attachment & Human Development, 14(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2012.672286

Stephenson, J., Linfoot, K., & Martin, A. (2000). Behaviours of concern to teachers in the early years of school. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 47(3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/713671118

Stoiber, K. C. (2004). Functional assessment and intervention system. Pearson.

Stoiber, K. C., & Gettinger, M. (2011). Functional assessment and positive support strategies for promoting resilience: Effects on teachers and high-risk children. Psychology in the Schools, 48(7), 686–706. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20587

Stoltz, S., van Londen, M., Deković, M., de Castro, B. O., & Prinzie, P. (2012). Effectiveness of individually delivered indicated school-based interventions on externalizing behavior. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 36(5), 381–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025412450525

Sutherland, K., Conroy, M., McLeod, B., Granger, K., Broda, M., & Kunemund, R. (2020). Preliminary study of the effects of BEST in CLASS–Elementary on outcomes of elementary students with problem behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 22(4), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300719900318

Sutherland, K. S., Conroy, M. A., Algina, J., Ladwig, C., Jessee, G., & Gyure, M. (2018a). Reducing child problem behaviors and improving teacher–child interactions and relationships: A randomized controlled trial of BEST in CLASS. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 42, 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.08.001

Sutherland, K. S., Conroy, M. A., McLeod, B. D., Algina, J., & Wu, E. (2018b). Teacher competence of delivery of BEST in CLASS as a mediator of treatment effects. School Mental Health, 10(3), 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9224-5

Sutherland, K. S., Conroy, M. A., Vo, A., Abrams, L., & Ogston, P. (2013). An initial evaluation of the teacher–child interaction direct observation system: Measuring teacher–child interaction behaviors in classroom settings. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 39(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534508412463814

Tapp, J., Wehby, J., & Ellis, D. (1995). A multiple option observation system for experimental studies: MOOSES. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 27(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03203616

Tipton, E., Pustejovsky, J. E., & Ahmadi, H. (2019). Current practices in meta-regression in psychology, education, and medicine. Research Synthesis Methods, 10(2), 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1339

Tompson, M. C., Connor, E. O., Kemp, G. N., Langer, D. A., & Asarnow, J. R. (2015). Depression in childhood and early adolescence: Parental expressed emotion and family functioning. Annals of Depression and Anxiety, 2(7), 1070.

Van den Noortgate, W., López-López, J. A., Marín-Martínez, F., & Sánchez-Meca, J. (2015). Meta-analysis of multiple outcomes: A multilevel approach. Behavior Research Methods, 47(4), 1274–1294. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0527-2

Vancraeyveldt, C., Verschueren, K., Van Craeyevelt, S., Wouters, S., & Colpin, H. (2015). Teacher-reported effects of the Playing-2-gether intervention on child externalising problem behaviour. Educational Psychology, 35(4), 466–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.860218

Vancraeyveldt, C., Verschueren, K., Wouters, S., Van Craeyevelt, S., Van den Noortgate, W., & Colpin, H. (2015). Improving teacher–child relationship quality and teacher-rated behavioral adjustment amongst externalizing preschoolers: Effects of a two-component intervention. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(2), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9892-7

Veenman, B., Luman, M., & Oosterlaan, J. (2017). Further insight into the effectiveness of a behavioral teacher program targeting ADHD symptoms using actigraphy, classroom observations and peer ratings. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1157. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01157

Veenman, B., Luman, M., Hoeksma, J., Pieterse, K., & Oosterlaan, J. (2019). A randomized effectiveness trial of a behavioral teacher program targeting ADHD symptoms. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(3), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716658124

Walker, H. M., & McConnell, S. R. (1988). Walker-McConnell scale of social competence and school adjustment: A social skills rating scale for teachers. Pro-Ed.

Wan, X., Wang, W., Liu, J., & Tong, T. (2014). Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-135

Wang, C., Hatzigianni, M., Shahaeian, A., Murray, E., & Harrison, L. J. (2016). The combined effects of teacher–child and peer relationships on children’s social-emotional adjustment. Journal of School Psychology, 59, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.09.003

Webster-Stratton, C. (2011). The incredible years: Parent, teacher, and child training series (IYS). In Preventing violence and related health-risking social behaviors in adolescents: An NIH State-of-the-Science conference (p. 73).

Webster-Stratton, C. (2012). Teacher classroom management strategies questionnaire. Retrieved from https://incredibleyears.com/for-researchers/measures/

Williford, A. P., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Whittaker, J. V., DeCoster, J., Hartz, K. A., Carter, L. M., Wolcott, C. S., & Hatfield, B. E. (2017). Changing teacher–child dyadic interactions to improve preschool children’s externalizing behaviors. Child Development, 88(5), 1544–1553. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12703

Williford, A. P., & Shelton, T. L. (2014). Behavior management for preschool-aged children. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(4), 717–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2014.05.008

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Supported by a PhD studentship funded by the University of Jeddah.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RA & DD: Identifying the research question, defined the inclusion and exclusion criteria, searched for studies, selected studies for inclusion criteria, extracted data from included studies, conducted the meta-analysis, evaluated risk of bias, and presented the results. RA: Drafted and finalised the write-up of the study. DD, CG, & KS: Provided supervision for the study, reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent to Publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aldabbagh, R., Glazebrook, C., Sayal, K. et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Teacher Delivered Interventions for Externalizing Behaviors. J Behav Educ 33, 233–274 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-022-09491-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-022-09491-4