Abstract

This paper studies the distribution of resources within Albanian families in 2012 using a collective consumption model with two alternative specifications: the first enables the estimation of the intrahousehold distribution of resources among male adults, female adults and children; the second extends the analysis to girls and boys. In line with previous evidence on gender inequality in Albania, the results show that the female share of resources is substantially lower with respect to the male share, and that sons receive a larger share of resources than daughters. Considering that Albania experienced massive migration and return of young men in the 20 years before the survey, we further analyze the potential migration-induced transfer of gender norms. We find that the time spent abroad by the husband of the main couple has little influence on woman’s relative position within the households, however it does seem to favor a more equal treatment between daughters and sons. This result suggests that gender norms are more persistent in adult couples, however gender attitudes towards offspring are more elastic to social change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the unitary model of the family, household decisions are analyzed under the hypothesis that the household is a single decision-maker unit that maximizes the welfare of its members and implicitly ensures a fair distribution of household resources. In this framework, the head of the household makes all the relevant decisions, including child, spouse consumption, and children’s human capital investments, as if decisions were optimal for the welfare of all household members. However, such behavior cannot be guaranteed a priori and the welfare consequences caused by unfair intrahousehold distribution or discriminatory decisions against female household members may be serious and motivate policy interventions. Rosenzweig (1986) and several recent empirical tests (Alam, 2012; de Brauw et al., 2014; Vijaya et al., 2014; Dunbar et al., 2013; Wang, 2014; Bargain et al., 2014; Betti et al., 2020) have consistently rejected the hypothesis of a single decision-maker household in developing and transition countries, where highly variable socio-economic conditions and culture may favor the rise of considerable intrahousehold inequality issues.

Culture and social values are important determinants of the persistent gender inequalities in both developing and developed countries. Social norms are crucial in shaping individual behaviors and several work have shown that cultural attitudes regarding the role of women in the family are transmitted across generations (Fernández & Fogli, 2009; Farre & Vella, 2013; Alesina et al., 2013; Giménez-Nadal et al., 2019; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2018). Fernández and Fogli (2009) draw their conclusions from the work behaviour of previous generations. Farre and Vella (2013) based their results on individuals’ opinions towards gender roles, finding that mother’s view towards the role of women in the labor market and the family is strongly correlated with that of her sons and daughters. Alesina et al. (2013) analyzes the historical roots of gender norms by looking at the link between the traditional use of plough techniques in agriculture and current gender norms. Instead, Giménez-Nadal et al. (2019) and Gimenez-Nadal et al. (2018) measure attitudes toward gender roles using time spent in housework observed at individual level of parents and their children’s families. Another branch of literature has shown that gender norms influences boys and girls individual behaviors at school such as results in math test scores (Nollenberger et al., 2016) or the choice of extracurricular activities (Marcén et al., 2020).

Several studies found a significant association between migration experiences and gender social norms, for instance Blau et al. (2011), Adserà and Ferrer (2016), Fernández (2007) have focused on labor market behavior of immigrant women in the US and Canada to study how gender norms in the country of origin affect labor supply. Recently Marcén and Morales (2019) have analyzed the role of culture on the gender division of household labor using data on early-arrival first and second generation immigrants living in the US. They find that the higher the culture of gender equality in the country of ancestry, the greater the equality in the division of housework. Looking at the relationship between migration and gender norms in a different prospective, some studies have analyzed whether international return migration transforms gender norms. Tuccio and Wahba (2018) for Jordan found that women with a family member returning from a more conservative Arab country were more likely to bear traditional gender norms than women in households with no migration experience. At a macro level, Ferrant and Tuccio (2015) studied how migration may either improve or challenge gender inequality according to the level of social institutions in the host country.

Using the most recent World Bank Living Standard Measurement Survey collected in Albania in 2012, we estimate the intrahousehold distribution of resources among female and male adults and children, and then among adults and children of different gender within a collective Engel curves system and test how this distribution is affected if the husband of the main couple is a return migrant. A first objective of the paper is to use a collective consumption model to identify gender imbalances among adults and children in Albanian households in relatively recent years, and after a period of growth and general poverty reduction.Footnote 1 Compared with previous estimation of intrahousehold welfare distribution (Dunbar et al., 2013; Mangiavacchi et al., 2018), this study is enriched by the analysis of gender inequality among children. As shown by Mangiavacchi and Piccoli (2018) and Giménez-Nadal et al. (2019), parental attitudes have long term impact on children’s outcomes and gender roles persist from generation to generation, as a consequence gender inequality among children could spread to their own families once adult.

Finally, the paper aims to test whether a past migration experience induces a transfer of gender social norms from the hosting country to the country of origin. To test this potential transfer we estimate the impact of past migration experience on the current distribution of household resources. To ensure the identification of the intrahousehold distribution of resources in in the context of extended families, we focus on the case in which the returned migrant is the husband of the main couple. We also extend the concept of intrahousehold inequality to educational opportunities and test how past migration influences the propensity to send both male and female children to school. The identification strategy for the effect of migration relies on the information on the distance (in minutes by car) of the family residence district from Valona –an important port intensively used as a starting point by migrants seeking to reach to Italy because of its proximity to the Italian coastline–, and on the district share of the population that spoke Italian in 1990 as exclusion restrictions. These instruments have been previously used to perform impact evaluation of migration on other outcomes in Albania (Piracha & Vadean, 2010; Cattaneo, 2012; Mendola & Carletto, 2012).

The results suggest that women’s share of resources is substantially lower than men’s share, with a small but significant improvement with respect to 2002 (Mangiavacchi et al., 2018). There is somewhat weaker evidence of intrahousehold gender discrimination also among children. Husband’s migration experience abroad has in general a positive impact on both males’ and females’ resource shares, ha+ving no significant impact on gender inequality among adults within the household. As to gender imbalances among children, the time fathers had spent abroad seems to have helped them establish a more egalitarian treatment between daughters and sons once back in the country of origin.

Gender Norms and Migration in Albania

Albania is a country where studying the governance of household resources is particularly relevant. After the Second World War, Albania was a rural society characterized by patriarchal family values. In vast rural areas, socio-economic activities were governed by the Kanun, a set of traditional laws inherited from the Middle Ages (Gjonca et al., 2008; Vullnetari, 2012). The Kanun gave males unquestioned authority within the household, implying for example that daughters could not inherit unless there were no sons. The communist regime enforced women’s educational policies that partially mitigated the patriarchal structure of Albanian households, but the family maintained a central role and patriarchal values resurfaced after the fall of the regime in the 1990s, with the risk of exposing women—and indirectly childrenFootnote 2—to vulnerable situations such as severe poverty and malnutrition. In addition, massive international migration outflows represented an additional concern for the Albanian family model that emerged after 1990.

In the Albanian tradition, especially during times of historical and political upheaval, migration is a normal practice. For example, the pre-communist migration was a consequence of the Ottoman occupation and gave rise to stable small Albanian communities in the South of Italy. Although Albanians have migrated to several countries around the world, the two biggest recipients of Albanians have been by far Greece and Italy. Estimates suggest that Greece and Italy together account for approximately 80% of the migrants (Vullnetari, 2012). Return migration to Albania is a relatively recent phenomenon. According to Piracha and Vadean (2010), over 70% of the returnees came back to Albania after 2001, when the socio-economic and political situation started to improve and one-third of the individuals who migrated after 1990 returned by 2005. A recent survey on return migration from INSTAT (2013) found that the returning flow increased after the global financial crisis.Footnote 3

Migration in Albania has relevant consequences for the family structure, the decision-making process within the household and intrahousehold inequality. The massive migration that took place after 1990 was dominated by young males leaving a socially relevant portion of female spouses and children behind with documented negative consequences for both. Giannelli and Mangiavacchi (2010) investigated the long-term effects of parental migration abroad on the schooling of children left behind in 2005 and found that parental migration had a negative effect on school attendance in the long term, with higher hazards of school drop-outs for children left behind and a higher impact for girls than for boys at secondary school age. These findings were confirmed by Mastrorillo and Fagiolo (2015), who performed a similar test for 2012. Mendola and Carletto (2012) examined the role of migration in affecting the labor market opportunities of female household members left behind in 2005; they found that females in families with a migrant abroad do less paid work and more unpaid work. Mangiavacchi et al. (2018) estimated a complete collective demand system for male and female adults and children, and the respective share of resources focusing on migrant-sending families in 2002; their findings suggest that female share of resources did not improve with husband’s migration.

The returning process of young males implied a natural change in the family structure; most of the returning Albanians used to live in extended families before migration, with nuclear families accounting for only 31.4%. This percentage increased to 37.1% in the host country and reached 45.9% upon return (INSTAT, 2013). Mendola and Carletto (2012) explored the consequences of the men’s return on female labor supply, suggesting a positive impact of men’s past migration experience on women’s empowerment: women with past family migration experience were significantly more likely to engage in self-employment and less likely to supply unpaid work. Lerch (2015) found fertility reduction and marriage postponement when community members had been abroad, especially when women could interact with networks of female migrants. These findings are in line with recent literature on the adjustment of family norms to those that prevail in their previous countries of destination in other countries (Ferrant & Tuccio, 2015; Tuccio & Wahba, 2018).

Data and Empirical Strategy

Estimation of the Intrahousehold Distribution of Resources

The estimation of intrahousehold distribution of resources relies on the collective framework (Chiappori, 1988, 1992), in which individual members’ preferences are explicitly accounted for in the household decision-making process. The interaction between household members is summarized by a rule governing the distribution of resources within the household, the so-called “sharing rule.” The collective framework permits identifying the sharing rule together with the structure of preferences and welfare functions of each household member, which are then used to analyze intrahousehold inequality issues.

The reference framework is that of collective consumption models. Early attempts at estimating collective consumption models, such as Browning et al. (1994), could not identify the level of household resources of each member although it was still possible to identify the impact of some variables on the sharing rule.Footnote 4 Recently, this lack of identification has been addressed by making use of information of separate consumption by each household member (Menon et al., 2012; Cherchye et al., 2012; Mangiavacchi et al., 2018; Menon et al., 2018). A second approach allows us to identify bounds on the level of the share of resources using revealed preferences inequalities (Cherchye et al., 2011), which substantially shrink when combined with Slutsky symmetry restrictions (Cherchye et al., 2015), and can achieve point identification under specific marriage market assumptions (Cherchye et al., 2017). Finally, a third method for identifying resource shares imposes additional restrictions on preference and/or the household allocation process (Lewbel & Pendakur, 2008; Lise & Seitz, 2011; Browning et al., 2013; Dunbar et al., 2013).

While most of these studies develop full demand systems, we make use of the identification strategy proposed by Menon et al. (2018) and Mangiavacchi et al. (2018), but without price variation, thus developing a collective Engel curves system as in Betti et al. (2020). As the identification strategy is based on individual-specific consumption information, the observation of suitable distribution factors is not strictly required, but their inclusion can substantially improve identification.Footnote 5

In order to analyze gender discrimination both from an adult’s and a child’s perspectives, two alternative household specifications are used: one with a man, a woman, and a child, and another with an adult, a son, and a daughter. In both cases the same theoretical model applies.Footnote 6

The household is composed of three members indexed as \(k = 1, 2, 3\), who decide via a bargaining process their optimal consumption levels of non-assignable and assignable goods, \({\mathbf {c}}_{k}\) and \({\mathbf {q}}_{k},\) respectively, given household income y. This decision problem can be represented by a two stage process. In the first stage family members agree on the division of household resources, such that each member is assigned the amount \(\phi _k\), and \(y=\phi _{1}+\phi _{2}+\phi _{3}.\) In the second stage each member maximizes her own utility subject to her private budget constraint

The solution of the individual problem produces a system of individual demand function that sum up to the household demand as

In Mangiavacchi et al. (2018) this system is specified as a QUAIDS (Banks et al., 1997), identifying the individual income effects and the sharing rules. Because unit-values are not available for all commodities in the 2012 ALSMS, the estimation of a standard demand system is not possible. Instead, in line with Bourguignon et al. (2009), we propose an alternative procedure based on the estimation of a collective Engel curves system with individual income effects, similar to Mangiavacchi et al. (2018) but without prices and part of the structure of the QUAIDS. For each commodity, a household level Engel curve is defined asFootnote 7

Clearly, in this specification the sharing rules \(\phi _k\) are not fully observed. Instead, it is possible to use assignable commodities expenditure to define the observed share of household income \(\sigma _{k}=\left( {\mathbf {p}}_{{\mathbf {q}}_k}^{\prime }{\mathbf {q}}^{k}+\frac{1}{3}{\mathbf {p}}_{{\mathbf {c}}}^{\prime }{\mathbf {c}}\right)/y\), and scale the observed individual expenditure by a correction term \(m_k({\mathbf {z}})\) that is a function of a set of variables \({\mathbf {z}}\) called “distribution factors”, which are assumed to alter the bargaining power of household members but not consumption preferences

In order to ensure that the sharing rules sum up to household income, i.e. \(\sum _k \phi _k = y\), the correction terms must respect \(\sum _k \sigma _k m_k({\mathbf {z}}) = 1\), which in the case of a 3-members household reads

By specifying the \(m_k({\mathbf {z}})\) function as a Cobb-Douglas, its logarithm becomes linear in \({\mathbf {z}}\), and the collective Engel curves system is define by the following equation

where coefficients \(\alpha\), \(\beta _k\) and \(\lambda _k\) are commodity specific, and the \(m_k({\mathbf {z}})\) correction terms are the same for all commodities. The system of equations defined by (5) is estimated by a non-linear seemingly unrelated regression allowing for correlation of the error terms, and is used to predict the relative sharing rules as

An analysis of the distribution of the predicted relative sharing rules is then used to reveal whether there exists gender discrimination within the household, both for adults and children.

The Impact of International Migration Experience on the Intrahousehold Distribution of Resources

Exposure to different practices and attitudes towards women in the destination country may drive institutional changes in origin countries. Essentially, return migrants bring back new ideas and narratives to their community members, which consequently shift the social norms and institutions in place at home. The past international migration exposure of the husband may act as a channel of norms transmission, influencing the set of norms that migrants have acquired in the country of origin. When migrants return to their origin countries, they bring back the newly acquired norms and those may spread around their communities. In this work, we aim to test whether the intrahousehold distribution of resources has been affected by the husband’s migration experience in European countries or in the US.

The empirical strategy used to analyze the impact of the migration experience on intrahousehold inequality is based on a post-estimation analysis. Ideally, the most appropriate strategy would be to include a variable indicating past international migration experience among the distribution factors \({\mathbf {z}}\). However, this would lead to biased results because such a variable should be a) exogenous and b) a proper distribution factor. Past migration experience clearly violates both assumptions because a) some unobservable factors are likely to influence both consumption choices and the decision to migrate, and b) because a past migration experience is likely to influence both consumption preferences and the intrahousehold bargaining process. A possible alternative strategy would be to use an instrumental variable estimator, but to the best of our knowledge the identification of a collective consumption model with an endogenous distribution factor has not yet been proved. Moreover, the quest for a good instrument would be harder than usual because the instrument would need to also be a proper distribution factor.

An alternative feasible strategy is to conduct the analysis using an endogenous binary variable model on the predicted relative sharing rules \({\widehat{r}}_k\) (Cameron & Trivedi, 2005; Wooldridge, 2010). Compared to treatment effects models, this model is robust to violations of the unconfoundedness assumption (or conditional independence assumption), where some unobservable factors may influence both the treatment and the outcome. The model is also more flexible than the linear IV models in the specification of the outcome equation, because the set of regressors in the selection equation can be different from the explanatory variables of the outcome equation. Still, to help identification, the explanatory variables for the treatment equation should include at least one exclusion restriction where an exogenous variable is significantly correlated with the endogenous variable but not with the outcome.

The model can be specified as

where \(o_{j}\) is the outcome variable for the j-th observation (the predicted share of resources assigned to each household member), \({\mathbf {v}_{\mathrm {j}}}\) are the exogenous covariates used to model outcome, \(t_{j}\) is the endogenous binary variable –the treatment, having a past migration experience– and \({\mathbf {k}}_{j}\) are the exogenous covariates used to model the endogenous binary variable. \(\nu _{j}\) and \(\mu _{j}\) are bi-variate normal error terms. It is assumed that at least one component in \({\mathbf {k}}_{j}\) is an independent source of variation in \(t_{j}\), uncorrelated with the outcome. The parameter \(\delta\) corresponds to the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) and to the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATET).

In addition to the analysis of intrahousehold inequality in the resource distribution, to analyze in more depth child gender discrimination issues, education opportunities are also considered. Thus, the endogenous binary variable model is also applied to the proportion of female children attending pre-school, primary school and secondary school.

Data and Sample Selection

The data used for the analysis is the Albania 2012 Living Standard Measurement Survey by INSTAT. The survey includes a sample of 6671 households (substantially larger than previous surveys, which interviewed 3600 households), randomly chosen on the basis of the 2011 Population and Housing Census via a two stage procedure: first 834 Primary Selection Units were randomly chosen to be representative of the whole territory, and second, 8 households were randomly chosen in each PSU (with an additional 4 in case of no response or no contact). The increase in the sample size had the main objective of having data representative at the prefecture level (12 prefectures divided into urban and rural areas), rather than region level (4 regions divided into urban and rural areas). It is a rich dataset containing information on household consumption, socio-economic conditions, and income sources. The survey records detail individual information on education, labor market participation, health, and migration history.

Intrahousehold gender inequality was analyzed both for adults and children, with two different specifications of family models: (i) one composed by a man, a woman, and a child, and (ii) one composed by an adult, a son, and a daughter. To estimate the sharing rule for both models, different samples are needed. In particular, in model (i) each family needed to have adults of opposite sex and at least a child, while model (ii) needed at least an adult and two children of a different sex. In both cases children were defined as being younger than 15.Footnote 8

For model (i), 3790 households were dropped because of household composition, plus another 1023 because of zero expenditure recorded for at least one household member. A few missing values in the explanatory variables further reduced the sample to 1832 households. For model (ii) 5646 households were dropped because of household composition, 383 observation had missing observations for individual expenditure of either the son or the daughter, and 176 households had zero expenditure for at least one household member. Few missing values in other variables reduced the sample to 437 households.

The collective Engel curves system was defined over five categories of consumption: food, clothing, housing, alcohol and tobacco, and other goods. On average, for the whole sample, Albanian households spent 67.5% of their budget on food, 5.5% on clothing, 22.1% on housing (including utilities, domestic services, small appliances, but not rent), 0.5% on alcohol and tobacco, and 4.3% on other goods (including personal care, services, leisure, and education expenditure). The average household expenditure was 381,330 Lek per month (about 330$).

The observed individual expenditure share (\(\sigma _k\)) was computed starting from assignable expenditures. For model (i) man and woman expenditures were composed by clothing and footwear expenditure for men and women, while child expenditure was composed by clothing, footwear, and education expenditure. Non-assignable expenditure was computed as a residual from total household expenditure. In order to account for possibly different household compositions, per-capita expenditures were computed for each household member category.Footnote 9 This was a way of scaling households with complex compositions to a three-member households in such a way that they were comparable. For instance, man expenditure was divided by the number of men, and so on. Non assignable expenditure was divided by the household size. Total household expenditure was recalculated summing per-capita assignable expenditures and three per-capita non-assignable expenditures. Finally, the shares of individual expenditures (\(\sigma _k\)) were computed as the sum of per-capita assignable and non-assignable expenditure divided by the recalculated total expenditure.

A similar procedure was followed for model (ii) where adult expenditure was the sum of clothing and footwear for men and women, while children clothing and footwear expenditure, both sons and daughters, equally split, but individual educational expenditures are available.

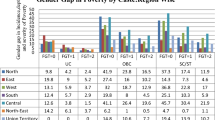

The summary statistics of the individual shares are presented in Table 1. A first inspection reveals that for model (i) the distribution seems rather equal, with a slightly larger share for the child. Model (ii) confirms a larger share for children and a substantial equity between sons and daughters.

In model (i), the distribution factors (\({\mathbf {z}}\)) used in the estimation were the age difference and the years of education difference of the main coupleFootnote 10 (woman minus man), the proportion of female children in the household, the average age of the children, and the prefecture level divorce ratio (n. of divorced per 1000 inhabitants). In model (ii), the distribution factors are age and education differences in the main couple, the divorce ratio, the relative average age of daughters with respect to sons and the prefecture level sex-ratio at birth.

The descriptive statistics of the budget shares, log of total expenditure, and distribution factors are presented in the first part of Table 2 both for model (i) and model (ii).

As to the post-estimation analysis, a number of additional variables were included, along with the distribution factors, for modeling the outcome equation. The most important explanatory variable is the treatment, that is whether the husband in the main couple had a past migration experience of at least three months and whether the spouse and children joined him in the destination country. At variance with previous studies that focus on any household member migration, the analysis focused on the male migrant from the household couple that was more likely to be responsible for household decisions. The main couple in multi-nuclear households was identified starting from the main husband: he had to be older than 25, younger than 70 and married or cohabiting. In those households with more than one male with these characteristics, the household head or, alternatively the older, was set to be the main husband. The main wife is identified by the spouse identification code of the main husband.

The additional explanatory variables included: an asset ownership index, regional dummies, the proportion of dependents in the household, whether there were more females than males in the household, the age of the husband of the main couple, whether the husband of the main couple had a university degree, the average years of education of the adults living in the household, the share of employees among the working age members within the household, whether both male and female partners of the main couple were employed (bi-active family) and the quantile of declared household income. The second part of Table 2 presents the summary statistics of these variables both for model (i) and for model (ii).

The identification strategy requires at least one exclusion restriction for having had a past migration experience, and we followed those studies considering that distance has a strong negative effect on migration by raising transaction costs and reduced information (Sahota, 1968; Schwartz, 1973) and the literature instrumenting migration making use of distances from border or ports (see for example, Kilic et al., 2009; Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2011; Alcaraz et al., 2012). We tested several distance measurements and the one that worked best for our study was the distance from the main port (Valona) in minutes by car.Footnote 11 Controlling for regions and urban location of households, the only impact of port proximity on household’s decision-making process should be via the instrument’s influence on past migration. In addition, following Kilic et al. (2009), an additional instrument was the district share of the population that spoke ItalianFootnote 12 in 1990. This variable was constructed using the 2005 Albanian Living Standard Measurement Survey, which was characterized by a particularly detailed information set about present and past international migration episodes.

The last analysis used different outcomes to test gender discrimination among children, namely the proportion of females attending pre-primary, primary, and secondary schools. In these regressions, distribution factors were replaced by the distance from school and the average age of children. In addition the samples sizes were different because the discriminant was the presence of children of specific school ages. The statistics for these variables are presented in Table 3.

Results

This study has several sets of results that for convenience are presented in the following subsections: first, the results on adult and child gender discrimination; second, the impact of return migration on the distribution of resources between male and female adults and children; and third, a set of robustness checks.

Intrahousehold Distribution of Resources Among Adults and Children

Table 4 present the results of the estimation of the system of Engel curves (5) for model (i), where a family is composed by a man, a woman, and a child. As for the estimation of demand systems, one of the budget shares had to be left out to avoid multi-collinearity (alcohol and tobacco). The coefficients of the individual income effects are in general precisely estimated, with several significant quadratic coefficients, revealing that a linear specification of the Engel curves would have been inappropriate.

As to the identification of the distribution factors, for the man correction term, \(m_{m}({\mathbf {z}})\), the significant parameters are the spouses’ education difference and the average age of children, both of which improve males’ bargaining power. For the women’s correction term, \(m_{w}({\mathbf {z}})\), more distribution factors are relevant. All distribution factors point to a reduction of women bargaining power, except for the age difference, which is not significant. The difference in education in the couple have similar coefficients with opposite sign, indicating that it does not influence much children resources, while the other distribution factors seem to act mostly between mothers and children. For instance, having more daughters than sons reduces women’s resources in favor of children. As to the average age of children the interaction seems more complex, the older the children the less men are willing to leave for them, but this is overcompensated by the reduction in women’s share of resources, so that overall older children get more resources.

The distribution of the predicted relative share of resources (\({\widehat{r}}_k\)) are presented in Figure 1. The left panel of the Figure presents the density functions of man, woman, and child, and the right panel depict how distribution of resources varies with the log of total household expenditure. The analysis reveals that women’s share of resources is substantially smaller than that of men and children. Children’s share tends to improve with household expenditure, but the difference between men and women is constant all along the expenditure distribution. Table 5 shows that on average men receive 34% of household resources, while women less than 28%. Overall children are in a better position. Compared with the observed shares (\(\sigma _{k}\)) in Table 1, which shows a substantial gender parity in assignable expenditure, the proposed model is able to identify strong levels of gender inequality within the household. The results are also consistent with estimates for 2002, which were obtained using a slightly different model (see Mangiavacchi et al., 2018). The t-statistics reveal that there has been a significant reduction in adult gender discrimination in the decade, but the country is still far from a gender equal distribution.

Table 6 presents the results of the estimation of the system of Engel curves for model (ii). Because of the much smaller sample size, coefficient’s estimates are less precise, with fewer significant coefficients, including those of the \(m_k({\mathbf {z}})\) function for adults. Significant coefficients, however are found for parents education difference and divorce ratio, which reduces sons’ share of resources in favor of daughters, and the sex-ratio at birth, an indicator of social preferences for sons,Footnote 13 which is found to increase the share of resources of sons with respect to daughters.

The analysis of the predicted share of resources (Figure 2) reveal that daughters have a smaller share of resources with respect to sons, especially in poorer families, although confidence intervals are much wider than in Figure 1 because the sample size is less than a quarter here. On average, sons get 40.5% of household resources, daughters 35.4%, and adults 24.1%. The difference between sons and daughters seems to reduce with household expenditure. Comparisons with previous results for Albania (Mangiavacchi et al., 2018) cannot be made because the 2002 survey did not allow to estimate sons and daughters shares of resources.

The Impact of International Migration Experience on the Intrahousehold Distribution of Resources

This section analyses the impact that the return of the husband who had migrated abroad has on intrahousehold gender inequality. The previous literature suggests that an international migration experience might change family-related behaviors, such as fertility choices, the decision to marry or female labor supply (Mendola & Carletto, 2012; Lerch, 2015). Similarly, it could change the migrant’s perception of gender roles, possibly resulting in different behavior once back home. For instance, if the migrant spent time in a Western European society where gender norms are more egalitarian, his view on household decision-making process could be more favorable to women.

This issue is investigated by means of an Endogenous Binary Model, where the outcomes –i.e. the predicted share of resources of man, woman and child– are regressed on a set of explanatory variables that include the past migration experience of the husband in the main couple or the past migration experience of the husband with spouse and children, instrumented using the distance from the main migration port (Valona) and the district share of population that spoke Italian in 1990. Discrimination of girls in school attendance is analyzed with the same method. The advantages of such a method are various and include the possibility of explaining the variability of the predicted share of household resources not only through the distribution factors, but also through an additional set of variables that would not be suitable as distribution factor. In addition, it is possible to analyze which factors influence the predicted share of resources of the third household member, which in the collective Engel curves system enters as a residual component.

Table 7 presents the results of the estimation with the treatment set as the past migration experience of the husband of the main couple in the household. Here the exclusion restrictions, the distance from Valona and the District share of population that spoke Italian in 1990, are significant at .05 and .01 respectively, with the expected negative sign for the distance from Valona and positive for the share of Italian speakers. As to the outcome equation, when the husband of the main couple has a past migration experience men and women shares of resources are significantly larger (by 1.6 and 0.7 percentage points respectively), while the children’s share is significantly lower (by 2.0 percentage points).

These results are in line with Mangiavacchi et al. (2018) finding that, even conditioned on receiving remittances, women do not improve their relative position (respect to men) during husband’s absence, and strengthen the idea that, even if the migration strategy is often seen as a means for economic growth, the welfare improvements for the family members left behind are doubtful (Giannelli & Mangiavacchi, 2010; Gibson et al., 2011; Mendola & Carletto, 2012; Antman, 2015). Similar results have been found for the case in which the past migration experience involved all the family (Table 8).

In contrast, the husband’s migration exposure has a positive impact on gender equality among sons and daughters (Table 9). Father’s migration increases resources devoted to daughters and decreases those devoted to sons. The time fathers had spent abroad seems to have helped them to establish a more egalitarian treatment between daughters and sons once back in the country of origin.

Table 10 analyses the impact of the past migration experience of the main husband on the proportion of daughters attending school by grade. The results suggest that a past migration experience of the main husband have a negative and significant impact on female enrollment in preschool and secondary school. As expected, compulsory schooling is not affected by the migration experience. These results confirm and extend previous findings from Giannelli and Mangiavacchi (2010) using 2005 data, where left-behind daughters were more likely to drop out of school than sons.

Robustness

To estimate the intrahousehold distribution of resources, one of the empirical choice was to drop all households for which assignable consumption is zero for at least one household member. This choice was made because, although zero expenditure on assignable consumption might be a deliberate choice, it may also be the outcome of infrequency of purchases. In that case, and if the distribution of zeros due to infrequency of purchases is not evenly distributed across household members, the resulting intrahousehold distribution of resources could be partially driven by a statistical issue rather than household consumption choices. To verify how much this could have been an issue, in Table 11 we report the predicted distribution of resources if model (i) was estimated without dropping zeros in assignable consumption. The results show a slightly more gender unequal distribution, but the distribution is in line with our main specification.

Another empirical choice that we had to take is related to the maximum age of children. We considered children all individuals aged less than 15. This choice is a direct consequence of the definition of expenditure on clothing for children by the Albanian statistical office. Nevertheless, as pointed out by Del Boca et al. (2017) parental investment on children might be smaller during high school. To this aim we already included the average age of children in our main analysis, finding that the older children the larger their share of resources, but to further investigate the question we replicated our main analysis keeping only households with children under the age of 12. The resulting distribution of resources, presented in Table 11, however points to the opposite direction, as families with younger children seem to devote a slightly smaller share of resources to children. This result may be explained by the fact that older children have a more developed personality and thus could have more bargaining power with respect to younger ones.

As to the estimation of the impact of past migration experiences on the intrahousehold distribution of resources, one possible question is why not analyzing directly the distribution of assignable consumption \(\sigma _k\) rather than the predicted share of resources \(\hat{r}_k\). Indeed, once controlling for the distribution factors the results should be pretty similar. This is confirmed by analyzing the first two columns of Table 12, which clearly highlight how the measured impact is almost identical.

Finally, a possibly more relevant concern about estimating the impact of past migration on the intrahousehold distribution of resources concerns the decision to apply an endogenous binary treatment regression rather than standard linear IV. While the former provides some advantages over the linear IV, in the third column of Table 12, for completeness we report the results of estimating the impact of past migration using a more standard instrumental variable approach. We performed this estimation using the recursive GMM option, which is more similar to the FIML performed in the main regressions and provides some efficiency gains with respect to the standard two-step approach. The results confirm a positive and significant impact of previous migration on men’ share of resources, with the additional advantage that the linear IV enables us to perform a weak identification test of the instrument. In particular, the joint F-test of the instruments returns a value of 7.75, which falls within the 10% LIML size (8.68) and 15% LIML size (5.33) of the Stock-Yogo (2005) critical values, indicating a small weak-instruments bias in our estimated coefficient.

Concluding Remarks

This study analyses the gender distribution of resources within Albanian households and whether it is influenced by a past migration experience of the husband of the main couple. The main objective of the paper is to verify whether gender discrimination is an issue in Albania, both among adults and children, and its relationship with the massive past migration flows experienced by the country. In addition, it analyses the link between daughters school enrollment and father’s past migration.

To this end, the analysis is based on the collective household framework, a theoretical and empirical setting that allows us to analyze the distribution of resources within the household. This aspect is typically neglected by the standard poverty and inequality analysis because the household is seen as a black-box whose decision processes are treated as if they were taken by the household head alone.

The results reveal that women have access to a smaller share of resources within the household with respect to men, both as adults and, to a lesser extent, as children. In comparative households composed by a man, a woman, and a child, women have as low as 27.9% of household resources, while men control more than 34%. A decade of growth and poverty reduction have produced a small but significant improvement in terms of gender equality from 2002 (Mangiavacchi et al., 2018), suggesting the idea that cultural traits and family norms are more persistent than policies and do not depend much on the economic cycle.

On top of that, a past international migration experience of the husband increases men’s share more (by 1.6%) than women’s share (0.7%), thus increasing the gender gap, and introduces a significant loss for children (− 2%). A similar pattern, with slightly larger figures, is found when the migration episode involved the wife and children.

This finding supports the growing literature on the negative side effects of international migration when the family is left behind in the country of origin. For example, Mangiavacchi et al. (2018) found that in 2002—a year characterized by a particularly large number of families with a migrant– family resources were redistributed in favor of men and children during the left behind period. Our results show a different pattern, with women benefiting from husband’s migration at the expenses of children.

On the contrary, it seems that the time fathers had spent abroad helped them to establish a more egalitarian treatment between daughters and sons once back in the country of origin. This finding reconciles this paper with the previous literature, confirming the hypothesis of the transfer of gender norms through return migration (Ferrant & Tuccio, 2015; Tuccio & Wahba, 2018). However, in this case, return migration does not promote better institutions at home through the transfer of norms from destination countries directly to family adult members, but encourages more egalitarian gender norms for future generations.

Data Availability

The data used by this work can be freely downloaded from the Albanian Institute of Statistics (INSTAT) website, under the micro-data section http://www.instat.gov.al/en/figures/micro-data/.

Code Availability

The statistical software used is Stata. The code used to perform the analysis is available upon request.

Notes

The fall of the communist regime implied the collapse of kindergartens and nurseries system that was put in place to favor women labor force participation (Palomba and Vodopivec, 2001).

A total of 133.544 Albanian migrants of the age group 18 years old and above have returned to Albania in the period 2009–2013 with most of the returns (53.4%) taking place during 2012 and 2013 (INSTAT, 2013).

These variables are commonly referred to as “distribution factors”, and are assumed to possibly influence the distribution of resources within the family but not consumption preferences.

Only a sketch of the theoretical framework is presented here. A detailed description of the model for a complete collective demand system can be found in Menon et al. (2018) and Mangiavacchi et al. (2018). As in the present work, also Betti et al. (2020) simplifies the framework to a system of collective Engel curves. However, as far as the intrahousehold distribution of resources is unrelated with the prices of the goods entering in the demand system, both estimation strategies would produce the same estimates for the sharing rule.

To save on notation, we omit indexing observations and budget shares categories. Thus, for instance, w instead of \(w_{ji}\) is the budget share of the j-th commodity for the i-th household, and \(\alpha\) instead of \(\alpha _j\) is the constant term estimated for commodity j. The same holds for individual incomes \(\phi _{k}\) and the \(\beta _k\) and \(\lambda _k\) coefficients.

This choice is driven by INSTAT’s definition of expenditure on children’s clothing and footwear, which is used for computing \(\sigma _k\) in Eq. (3). The variable is recorded only for children under 15.

This specification implicitly assumes equal distribution of consumption within each group. Such limitation, however, cannot be overcome without individual consumption data for at least one good.

The main couple is defined as the oldest working age couple in the household.

This was computed using Google Maps APIs, taking the family residence district center as reference for the starting location. We also tested the distance from Kakavia as an additional instrument, being Kakavia the main border crossing between Albania and Greece. In the end it was not included because it never turned out significant, probably because migration to Greece is mostly seasonal and the stay is usually shorter than 3 months.

We also tested other languages, but they resulted non significant.

INSTAT (2014) highlights how unbalanced sex-ratios at birth in most Albanian prefecture is probably the result of selective abortion. Thus, higher sex-ratios at birth may indicate stronger social preferences for boys with respect to girls.

References

Adserà, A., & Ferrer, A. (2016). Occupational skills and labour market progression of married immigrant women in Canada. Labour Economics, 39, 88–98.

Alam, S. (2012). The effect of gender-based returns to borrowing on intra-household resource allocation in rural Bangladesh. World Development, 40(6), 1164–1180.

Alcaraz, C., Chiquiar, D., & Salcedo, A. (2012). Remittances, schooling, and child labor in Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 97(1), 156–165.

Alesina, A., Giuliano, P., & Nunn, N. (2013). On the origins of gender roles: Women and the plough. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2), 469–530.

Antman, F. M. (2015). Gender discrimination in the allocation of migrant household resources. Journal of Population Economics, 28(3), 565–592.

Banks, J., Blundell, R., & Lewbel, A. (1997). Quadratic Engel curves and consumer demand. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 79(4), 527–39.

Bargain, O., Donni, O., & Kwenda, P. (2014). Intrahousehold distribution and poverty: Evidence from Cote d’Ivoire. Journal of Development Economics, 107, 262–276.

Betti, G., Mangiavacchi, L., & Piccoli, L. (2020). Women and poverty: Insights from individual consumption in Albania. Review of Economics of the Household, 18(1), 69–91.

Blau, F. D., Kahn, L. M., & Papps, K. L. (2011). Gender, source country characteristics, and labor market assimilation among immigrants. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1), 43–58.

Bourguignon, F., Browning, M., & Chiappori, P. A. (2009). Efficient intra-household allocations and distribution factors: Implications and identification. Review of Economic Studies, 76(2), 503–528.

Brauw de, A., Gilligan, D. O., Hoddinott, J., & Roy, S. (2014). The impact of Bolsa Familia on women’s decision-making power. World Development, 59, 487–504.

Browning, M., Bourguignon, F., Chiappori, P., & Lechene, V. (1994). Income and outcomes: A structural model of intrahousehold allocation. Journal of Political Economy, 102, 1067–1096.

Browning, M., Chiappori, P., & Lewbel, A. (2013). Estimating consumption economies of scale, adult equivalence scales, and household bargaining power. Review of Economic Studies. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdt019.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. Cambridge University Press.

Cattaneo, C. (2012). Migrants’ international transfers and educational expenditure. Economics of Transition, 20(1), 163–193.

Cherchye, L., De Rock, B., & Vermeulen, F. (2011). The revealed preference approach to collective consumption behaviour: Testing and sharing rule recovery. The Review of Economic Studies, 78(1), 176–198.

Cherchye, L., De Rock, B., & Vermeulen, F. (2012). Married with children: A collective labor supply model with detailed time use and intrahousehold expenditure information. The American Economic Review, 102(7), 3377–3405.

Cherchye, L., De Rock, B., Lewbel, A., & Vermeulen, F. (2015). Sharing rule identification for general collective consumption models. Econometrica, 83(5), 2001–2041.

Cherchye, L., Demuynck, T., De Rock, B., & Vermeulen, F. (2017). Household consumption when the marriage is stable. American Economic Review, 107(6), 1507–1534.

Chiappori, P. A. (1988). Rational household labor supply. Econometrica, 56(1), 63–90.

Chiappori, P. A. (1992). Collective labor supply and welfare. Journal of Political Economy, 100(3), 437–67.

Chiappori, P. A., & Kim, J. H. (2017). A note on identifying heterogeneous sharing rules. Quantitative Economics, 8(1), 201–218.

Del Boca, D., Monfardini, C., & Nicoletti, C. (2017). Parental and child time investments and the cognitive development of adolescents. Journal of Labor Economics, 35(2), 565–608.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Córdova, E. L., Pería, M. S. M., & Woodruff, C. (2011). Remittances and banking sector breadth and depth: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 95(2), 229–241.

Dunbar, G., Lewbel, A., & Pendakur, K. (2013). Children’s resources in collective households: Identification, estimation, and an application to child poverty in Malawi. The American Economic Review, 103(1), 438–71.

Dunbar, G. R., Lewbel, A., Pendakur, K., et al. (2017). Identification of random resource shares in collective households without preference similarity restrictions. Technical report. Ottawa: Bank of Canada.

Farre, L., & Vella, F. (2013). The intergenerational transmission of gender role attitudes and its implications for female labour force participation. Economica, 80(318), 219–247.

Fernández, R. (2007). Women, work, and culture. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(2–3), 305–332.

Fernández, R., & Fogli, A. (2009). Culture: An empirical investigation of beliefs. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 1(1), 146–177.

Ferrant, G., & Tuccio, M. (2015). South-south migration and discrimination against women in social institutions: A two-way relationship. World Development, 72, 240–254.

Giannelli, G., & Mangiavacchi, L. (2010). Children’s schooling and parental migration: Empirical evidence on the “left behind’’ generation in Albania. Labour, 24, 76–92.

Gibson, J., McKenzie, D., & Stillman, S. (2011). The impacts of international migration on remaining household members: Omnibus results from a migration lottery program. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(4), 1297–1318.

Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., Molina, J. A., & Zhu, Y. (2018). Intergenerational mobility of housework time in the United Kingdom. Review of Economics of the Household, 16(4), 911–937.

Giménez-Nadal, J. I., Mangiavacchi, L., & Piccoli, L. (2019). Keeping inequality at home: The genesis of gender roles in housework. Labour Economics, 58, 52–68.

Gjonca, A., Aassve, A., & Mencarini, L. (2008). Trends and patterns, proximate determinants and policies of fertility change: Albania. Demographic Research, 19(11), 261–292.

INSTAT. (2013). Return migration and reintegration in Albania. Dublin: INSTAT.

INSTAT. (2014). Population and population dynamics in Albania: New demographic horizons. Dublin: INSTAT.

Kilic, T., Carletto, C., Davis, B., & Zezza, A. (2009). Investing back home return migration and business ownership in Albania1. Economics of Transition, 17(3), 587–623.

Lerch, M. (2015). Does indirect exposure to international migration influence marriage and fertility in Albania? Journal of Population Research, 32(2), 95–114.

Lewbel, A., & Pendakur, K. (2008). Estimation of collective household models with Engel curves. Journal of Econometrics, 147(2), 350–358.

Lise, J., & Seitz, S. (2011). Consumption inequality and intra-household allocations. The Review of Economic Studies, 78(1), 328–355.

Mangiavacchi, L., & Piccoli, L. (2018). Parental alcohol consumption and adult children’s educational attainment. Economics & Human Biology, 28, 132–145.

Mangiavacchi, L., Perali, F., & Piccoli, L. (2018). Intrahousehold distribution in migrant-sending families. Journal of Demographic Economics, 84(1), 107–148.

Marcén, M., & Morales, M. (2019). Gender division of household labor: How does culture operate? GLO Discussion Paper no. 373.

Marcén, M., Morales, M., & Sevilla, A. (2020). Gender stereotyping in sports. IZA Discussion Paper no. 13470.

Mastrorillo, M., & Fagiolo, G. (2015). International migration and school enrollment of the left-behinds in Albania: A note. Eastern European Economics, 53(3), 242–254.

Mendola, M., & Carletto, C. (2012). Migration and gender differences in the home labour market: Evidence from Albania. Labour Economics, 19(6), 870–880.

Menon, M., Pagani, E., & Perali, F. (2012). A characterization of collective individual expenditure functions. Working Papers 20/2012, University of Verona, Department of Economics.

Menon, M., Perali, F., & Piccoli, L. (2018). Collective consumption: An application to the passive drinking effect. Review of Economics of the Household, 16(1), 143–169.

Nollenberger, N., Rodríguez-Planas, N., & Sevilla, A. (2016). The math gender gap: The role of culture. American Economic Review, 106(5), 257–61.

Palomba, G., & Vodopivec, M. (2001). Financing, efficiency, and equity in Albanian education (Vol. 512). Washington D.C.: World Bank Publications.

Piracha, M., & Vadean, F. (2010). Return migration and occupational choice: Evidence from Albania. World Development, 38(8), 1141–1155.

Rosenzweig, M. R. (1986). Program interventions, intrahousehold distribution and the welfare of individuals: Modelling household behavior. World Development, 14(2), 233–243.

Sahota, G. S. (1968). An economic analysis of internal migration in Brazil. The Journal of Political Economy, 76, 218–245.

Schwartz, A. (1973). Interpreting the effect of distance on migration. The Journal of Political Economy, 81, 1153–1169.

Tuccio, M., & Wahba, J. (2018). Return migration and the transfer of gender norms: Evidence from the middle east. Journal of Comparative Economics, 46(4), 1006–1029.

Vijaya, R. M., Lahoti, R., & Swaminathan, H. (2014). Moving from the household to the individual: Multidimensional poverty analysis. World Development, 59, 70–81.

Vullnetari, J. (2012). Women and migration in Albania: A view from the village. International Migration, 50(5), 169–188.

Wang, S. Y. (2014). Property rights and intra-household bargaining. Journal of Development Economics, 107, 192–201.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT press.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for comments and suggestions from the editor and two anonymous referees. The paper has also benefited from the valuable comments and suggestions of Agnes Quisumbing and Michèle Tertilt.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Trento within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This work was financially supported by United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research, project “Gender and Development” and Spanish Minister of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (Grant Number ECO2015-63727-R).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mangiavacchi, L., Piccoli, L. Gender Inequalities Among Adults and Children: Exposure to Migration and the Evolution of Social Norms in Albania. J Fam Econ Iss 43, 546–564 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09787-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09787-z