Abstract

This study introduces a new collective complete demand system with individual Engel effects that is easy to estimate and permits undertaking policy analysis at the individual rather than household level. Previous estimations of collective demand were limited to single equations. The empirical application investigates the passive drinking effect, that is, whether consumption of alcohol affects the distribution of resources among household members and their level of wellbeing. The results show that a high level of alcohol consumption of one household member significantly affects the allocation of household resources and suggest thought-provoking policy implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We share the view of Dunbar et al. (2013) who allow for externalities of private assignable goods on the utilities of other household members, but do not allow for externalities that affect household resource allocations or the expenditure patterns of other household members. According to these authors, smoking can be used as an identifying assignable good even if smoking may make other household members unhappy, but not if smoking makes other household members spend more than otherwise on household cleaning products.

Unlike Dunbar et al. (2013) we estimate a system of demand equations with the collective consumption theory restrictions imposed. The system estimation allows the recovery of individual welfare functions.

Social and environmental circumstances are known to be relevant determinants of alcohol use and abuse. Many studies show that personality traits are somehow related to alcohol consumption (Cloninger 1987; Sher and Trull 1994; Cooper et al. 1995). Disinhibitory personality traits, such as sensation seeking and impulsivity, are the main personality traits related to alcohol consumption both in non-alcoholics and in alcoholics (Cloninger 1987; Knorring et al. 1987; Wills et al. 1994; Andrew and Cronim 1997), while there is evidence that anxiety influences alcohol consumption in alcoholics only (Chinnian et al. 1994). To the best of our knowledge, there is no empirical evidence that relates a selfish or despotic control over resources to alcohol use. It is more plausible that regular heavy drinking may lead to neglecting the needs of the other members of the household.

Individual health-related characteristics may also affect marriage choices. Using data from the National Longitudinal Study, Fu and Goldman (1996) find that persons with unhealthy behaviors, such as high levels of alcohol consumption and the use of drugs, and with physical characteristics that are associated with poorer health status, such as obesity and short stature, have lower marriage rates than their healthier counterparts. Chiappori et al. (2016) develop a bi-dimensional matching model where the dimensions are education and smoking status. They derive predictions about equilibrium matching patterns and how individuals with different smoking habits marry depending on their education level.

In order to recover the underlying structure of the collective model, we use the available information about the assignable consumption of clothing, alcohol, and other gender related expenditures, such as perfume, jewels, and bags. The skewed consumption of assignable goods induces an income redistribution effect within the couple. For example, at the same level of total expenditure, families with a male heavy drinker may spend less on goods for women. Our empirical identification strategy intends to capture these income reallocation effects.

The centralized and decentralized program are linked together by a one-to-one relationship between the Pareto weight μ and the sharing rule as illustrated in Proposition 2 by Browning et al. (2013) where the Pareto weight is equal to the ratio of the marginal effect of the sharing rule on the indirect utility of member 1 and member 2.

Throughout the paper we use the terms “total expenditure” and “income” interchangeably.

The assignment of half the committed expenditure to each partner of the couple is used here to illustrate the derivation of individual demands but has no implications for the estimation of the collective demand system because the term \(\ln A({\bf{p}})\) is specified at the household level.

Distribution factors are variables that do not affect either individual preferences or the budget constraint but do influence the balance of power between family members and their optimal choices.

Because our demand system is in shares the sharing rule ϕ 1 = y 1 m takes the following logarithmic form \(\ln {\phi _1} = \ln {y_1} + \ln m\left( {{{\bf{p}}_{{{\bf{q}}^1}}},{{\bf{p}}_{{{\bf{q}}^2}}},{\bf{z}}} \right)\). We define ln y k = ln(y σ k ) = σk ln y, where the resource share σ k is defined as σ k = \(\left( {{\bf{P}}_{{q^{\,k}}}^\prime {{\bf{q}}^k} + {\bf{P}}_c^\prime {{\bf{c}}^k}} \right)\) with σ 1 + σ 2 = 1. The resource share σ k measures the proportion of household resources consumed by member k. Household resources allocated to member 2 are then measured by \(\ln {\phi _2} = \ln y - \ln {\phi _1} = {\sigma _2}\ln y - \ln m\).

The share of alcohol consumption consumed by the male partner is computed from individual information on the consumed quantity of different alcoholic beverages available in the ISTAT 2002 survey on lifestyle and health conditions. First, the individual quantities of different alcoholic beverages are transformed in grams of pure alcohol as in Giannelli et al. (2013) and then the share of grams of pure alcohol consumed by the male partner is computed. The hotdeck method replaces missing information for a non-respondent with observed values from a respondent with similar characteristics. This statistical matching method implies partitioning the sample according to characteristics of interest common to the two surveys. The missing value is replaced with a random draw from a sample partition. The application of the hotdeck method to the individual share of family alcohol consumption ensures that the predicted share is bounded between 0 and 1 and no alcohol consumption is assigned to members of households with zero alcohol expenditure. The variables chosen to partition the sample are the educational background of the head of the household, household head working position (low-skilled worker, white collar, self-employed), household located in the North, a working wife, household head is older than 55, and a dichotomous variable equal to one if one or both partners of the couple smokes. In the original sample the proportion of alcohol consumed by the husband is on average 0.720, with a standard deviation of 0.287. Once imputed, the same variable averages at 0.710 with a standard deviation of 0.285. More details on the imputation are available upon request.

Atella et al. (2003) estimate a complete quadratic demand system using a time series of cross-sections of Italian household budgets including, in turn, aggregate price indexes available from ISTAT and unit values constructed a la Lewbel (1989). The results show that the matrix of compensated price elasticities is negative semidefinite only if estimated unit values are used. In order to have a counterfactual experiment, the Atella et al. (2003) study also considers a household survey with actual unit values and compare them with Lewbel-type unit values. The experiment shows that in most cases unit values maintain the relevant characteristics of the distribution of actual unit values. Overall, the study concludes that reconstructed unit values are better than aggregate price indexes for sound demand and welfare analysis.

The initial sample comprises 80,358 households. The selection of married couples without children restricts the sample to 14,686 observations. The further exclusion of relatively older couples with at least one retired member, in order to select only couples belonging to the same stage of the life cycle, leads to another cut of about 72.5%. The final sample size is obtained keeping only families with positive expenditure of both men’s and women’s clothing, because clothing is our main source of identification of the sharing rule.

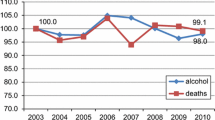

The choice of defining heavy drinkers on the basis of budget share rather than quantity is mainly due to the lack of direct information on quantities in the expenditure survey. As shown in Fig. 1, the conditional average budget share of alcohol is stable along the total expenditure distribution at around 2%. In levels, the wealthy spend for the home consumption of alcohol much more than the poor (the difference is significant at the 0.1% level). Because of quality effects, this does not mean that the wealthy drink at home more than the poor.

If an average quality beer-can costs about 0.5 Euro in the supermarket, then the quantity is about 220 beer-cans a month or about 10 bottles a month of a high quality wine.

Christmas and New Year celebrations are likely to increase alcohol expenditure.

In collective models, it is common to include marriage market factors such as the sex ratio or the divorce ratio (Grossbard-Shechtman 1993, 2003) in the sharing rule. The sex ratio, in particular, has been shown to be linked to individual alcohol consumption (Porter 2016), possibly through the distribution of household resources. However, in our sample, there is too little variation at regional level for both marriage market factors, and thus it is not possible to include them in the specification of the sharing rule.

In Italy, there have always been regional differences in alcohol consumption. Southerners tend to drink less than those living in the north of the country (Scafato et al. 2009). This consumption pattern may also be attributed to warmer temperatures in the south regions.

The estimates of the parameters of the sharing rule are robust to different specifications of the distribution factors, such as defining the ratio between husband’s age and wife’s age, and husband’s education and wife’s education.

Bootstrapped standard errors come from 1,000 bootstrap replications of the full sample.

Also the Banks et al. (1997) estimates reflect a cohort effect because the authors use a UK sample of repeated cross-sections for the period 1970–1986.

Our results confirm previous findings of an overall larger share of resources for men in Italy (Mangiavacchi and Rapallini 2014).

A household member is the main consumer if he/she is responsible for at least 75% of household alcohol consumption. In 85% of cases the main drinker is the husband.

In the sample, 52.8% of women belonging to the low tail of the total expenditure distribution are employed. In the upper tail, women’s participation rate is about 72%.

References

Adamo, D. & Orsini, S. (2006). L’uso e l’abuso di alcol in italia. Comunicati e note per la stampa, Istat - Istituto nazionale di statistica.

Amemiya, T. (1978). On a two-step estimation of a multivariate logit model. Journal of Econometrics, 8(1), 13–21.

Amemiya, T. (1979). The estimation of a simultaneous-equation tobit model. International Economic Review, 20(1), 169–181.

Amemiya, T. (1985). Advanced Econometrics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Andrew, M., & Cronim, C. (1997). Two measures of sensation seeking as predictors of alcohol use among high school males. Personality and Individual Differences, 22(3), 393–527.

Arias, C., Atella, V., Castagnini, R., & Perali, F. (2003). Estimation of the sharing rule between adults and children and related equivalence scales within a collective consumption framework. In C. Dagum & G. Ferrari (Eds.), Household behavior, equivalence Scales, welfare and poverty. New York, NY: Physica-Verlag.

Aristei, D., Perali, F., & Pieroni, L. (2008). Cohort, age and time effects in alcohol consumption by italian households: A double-hurdle approach. Empirical Economics, 35(1), 29–61.

Atella, V., Menon, M., & Perali, F. (2003). Estimation of unit values in cross sections without quantity information. In C. Dagum & G. Ferrari (Eds.), Household Behavior, Equivalence Scales, Welfare and Poverty. New York, NY: Physica-Verlag.

Banks, J., Blundell, R., & Lewbel, A. (1997). Quadratic engel curves and consumer demand. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 79(4), 527–539.

Barten, A. P. (1964). Family Composition, Prices and Expenditure Patterns. London: Butterworth.

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81(4), 813–846.

Bekker, P. A., Wansbeek, T. J., & Kapteyn, A. (1985). Errors in variables in econometrics: New developments and recurrent themes. Statistica neerlandica, 39(2), 129–141.

Borelli, S., & Perali, F. (2003). Drug consumption and intra-household distribution of the resources: The case of qat in an african society. In C. Dagum & G. Ferrari (Eds.), Household Behavior, Equivalence Scales, Welfare and Poverty. New York, NY: Physica-Verlag.

Browning, M., & Chiappori, P. A. (1998). Efficient intra-household allocations, a general caracterization and empirical tests. Econometrica, 66(6), 1241–1278.

Browning, M., Bourguignon, F., Chiappori, P. A., & Lechene, V. (1994). Incomes and outcomes: A structural model of intrahousehold allocation. Journal of Political Economy, 102(6), 1067–1096.

Browning, M., Chiappori, P. A., & Lewbel, A. (2013). Estimating consumption economies of scale, adult equivalence scales, and household bargaining power. Review of Economic Studies, 80(4), 1267–1303.

Caiumi, A., & Perali, F. (2014). Who bears the full costs of children? Empirical Economics, 1, 1–22.

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-hispanic americans in the 21st century. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of American, 112(49), 15078–15083.

Chavas, J. P., Menon, M., & Perali, F. (2014). The sharing rule: Where is it? Department of Economics, University of Verona, Working Paper Series.

Chiappori, P. A., Oreffice, S., and Quintana-Domeque, C. (2016). Bidimensional matching with heterogeneous preferences: Education and smoking in the marriage market. Journal of the European Economic Association, forthcoming.

Chiappori, P. A. (1988). Rational household labor supply. Econometrica, 56(1), 63–90.

Chiappori, P. A. (1992). Collective labor supply and welfare. Journal of Political Economy, 100(3), 437–467.

Chinnian, R. R., Taylor, L. R., Al-Subaie, A., & Sugumar, A. (1994). A controlled study of personality patterns in alcohol and heroin abusers in saudi arabia. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 26(1), 85–88.

Cloninger, C. R. (1987). Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science, 236(4800), 410–416.

Cook, Philip J., & Moore, Michael J. (2000). Alcohol. In A. J. Culyer & J. P. Newhouse, (Eds.), Handbook of Health Economics. Elsevier.

Cooper, M. L., Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Mudar, P. (1995). Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 990–1005.

Deaton, A., & Muellbauer, J. (1980a). An almost ideal demand system. American Economic Review, 70, 321–326.

Deaton, A. & Muellbauer, J. (1980b). Economics and Consumer Behavior. Cambridge University Press.

Deaton, A., Ruiz-Castillo, J., & Thomas, D. (1989). The influence of household composition on household expenditure patterns: Theory and spanish evidence. Journal of Political Economy, 97(1), 179–200.

Dunbar, G. R., Lewbel, A., & Pendakur, K. (2013). Children’s resources in collective households: Identification, estimation, and an application to child poverty in malawi. American Economic Review, 103(1), 438–471.

Fu, H., & Goldman, N. (1996). Incorporating health into models of marriage choice: Demographic and sociological perspectives. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58(3), 740–758.

Giannelli, G. C., Mangiavacchi, L., & Piccoli, L. (2013). Do parents drink their children’s welfare? Intra-household allocation of time between market labour, domestic work and child care in Russia. IZA Journal of Labor and Development, 2(1), 13.

Gill, L., & Lewbel, A. (1992). Testing the rank and definiteness of estimated matrices with applications to factors, state space, and ARMA models. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 87(419), 766–776.

Goldberger, A. S. (1972). Maximum-likelihood estimation of regressions containing unobservable independent variables. International Economic Review, 13(1), 1–15.

Gorman, W. M. (1976). Tricks with utility functions. In M. J. Artis & A. R. Nobay (Eds.), Proceedings of the 1975 AUTE conference, essays in economic analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grossbard-Shechtman, Shoshana (1993). On the economics of marriage: A theory of marriage labor and divorce. Boulder CO: Westview Press.

Grossbard-Shechtman, Shoshana (2003). A consumer theory with competitive markets for work in marriage. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 31(6), 609–645.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Heien, D., & Pompelli, G. (1987). Stress, ethnic and distribution factors in a dichotomous response model of alcohol abuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 48(5), 450–455.

Heien, D., & Roheim, C. A. (1990). Demand systems estimation with microdata: A censored regression approach. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 8(3), 365–371.

Hoderlein, S., & Mihaleva, S. (2008). Increasing the price variation in a repeated cross section. Journal of Econometrics, 147(2), 316–325.

Lewbel, A. (1985). A unified approach to incorporating demographic or other effects into demand systems. Review of Economic Studies, 70(1), 1–18.

Lewbel, A. (1989). Identification and estimation of equivalence scales under weak separability. Review of Economic Studies, 56(2), 311–316.

Maddala, G. S. (1983). Limited-dependent and qualitative variables in Econometrics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mangiavacchi, L., & Rapallini, C. (2014). Self-reported economic condition and home production: Intra-household allocation in italy. Bulletin of Economic Research, 66(3), 279–304.

McLaren, K. R., & Yang, O. (2016). A class of demand systems satisfying global regularity and having complete rank flexibility. Empirical Economics, 51(1), 315–337.

Menon, M., Perali, F., & Veronesi, M. (2014). Recovering individual preferences for non-market goods: A collective travel cost model. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 96(2), 438–457.

Mill, J. S. (1857). Principles of Economics. London: Parker.

Ólafsdóttir, Thorhildur, & Ásgeirsdóttir, TinnaLaufey (2015). Gender differences in drinking behavior during an economic collapse: Evidence from iceland. Review of Economics of the Household, 13(4), 975–1001.

Perali, F., & Chavas, J. P. (2000). Estimation of censored demand equations from large cross-section data. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 82(4), 1022–1037.

Perali, F. (2000). Microeconomia Applicata: Volume Primo. Rome, Italy: Carocci.

Perali, F. (2003). The behavioral and welfare analysis of consumption. The cost of children, equity and poverty in Colombia. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publisher.

Porter, Maria (2016). How do sex ratios in China influence marriage decisions and intra-household resource allocation? Review of Economics of the Household, 14(2), 337–371.

Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, Massachussetts: Harvard University Press.

Rubin, D. B., & Schenker, N. (1986). Multiple imputation for interval estimation for simple random samples with ignorable nonresponse. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 81(394), 366–374.

Scafato, E., Ghirini, S., Galluzzo, L., Farchi, G., & Gandin, C. (2009). Rapporto su raccolta e analisi centralizzata dei flussi informativi e dati per il monitoraggio dell’impatto dell’uso e abuso dell’alcol sulla salute in italia. Roma: Osservatorio Nazionale Alcol CNESPS–Istituto Superiore di Sanita.

Seccombe, W. (1995). Weathering the storm. New York, NY: Verso.

Sher, K. J., & Trull, T. J. (1994). Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: Alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103(1), 92–102.

Shield, K. D., Rehm, J., Gmel, G., Rehm, M. X., & Allamani, A. (2013). Alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence, and related mortality in italy in 2004: Effects of treatment-based interventions on alcohol dependence. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 8(1), 1–10.

Shonkwiler, J. S., & Yen, S. T. (1999). Two-step estimation of a censored system of equations. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 82(4), 972–982.

Shrestha, V. (2016). Do young adults substitute cigarettes for alcohol? Learning from the master settlement agreement. Review of Economics of the Household, 1–25, doi:10.1007/s11150-016-9337-x.

Sloan, F. A., Ostermann, J., Conover, C., Donald, H. T., & Picone, G. (2006). The Price of Smoking, Vol. 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Suhrcke, M., Nugent, R. A., Stuckler, D., & Rocco, L. (2006). Chronic disease: An economic perspective. London: Oxford Health Alliance.

von Knorring, L., von Knorring, A. L., Smigan, L., Lindberg, U. L. F., & Edholm, M. (1987). Personality traits in subtypes of alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 48(6), 523–527.

WHO. (2009). Handbook for action to reduce alcohol-related harm. Technical report. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Wills, T. A., Vaccaro, D., & McNamara, G. (1994). Novelty seeking, risk taking, and related constructs as predictors of adolescent substance use: An application of cloninger’s theory. Journal of Substance Abuse, 6(1), 1–20.

Zellner, A. (1970). Estimation of regression relationships containing unobservable independent variables. International Economic Review, 11(3), 441–454.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for insightful comments and suggestions from many seminar and conference participants, and especially Rolf Aaberge, Francesco Avvisati, Sara Borelli, Eve Caroli, Andrew Clark, Ugo Colombino, Sergio De Stefanis, Shoshana Grossbard, Snorre Kverndokk, Lucia Mangiavacchi, Eleonora Matteazzi, Eugenio Peluso, Marcella Veronesi, Knut Wangen, Luca Zarri, and as well as the editor and two anonymous referees. All errors and omissions are our own. The article is part of a research project financed by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (grant n. ECO2015-63727-R).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Menon, M., Perali, F. & Piccoli, L. Collective consumption: an application to the passive drinking effect. Rev Econ Household 16, 143–169 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-017-9384-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-017-9384-y