Abstract

Educational leaders’ effectiveness in solving problems is vital to school and system-level efforts to address macrosystem problems of educational inequity and social injustice. Leaders’ problem-solving conversation attempts are typically influenced by three types of beliefs—beliefs about the nature of the problem, about what causes it, and about how to solve it. Effective problem solving demands testing the validity of these beliefs—the focus of our investigation. We analyzed 43 conversations between leaders and staff about equity related problems including teaching effectiveness. We first determined the types of beliefs held and the validity testing behaviors employed drawing on fine-grained coding frameworks. The quantification of these allowed us to use cross tabs and chi-square tests of independence to explore the relationship between leaders’ use of validity testing behaviors (those identified as more routine or more robust, and those relating to both advocacy and inquiry) and belief type. Leaders tended to avoid discussion of problem causes, advocate more than inquire, bypass disagreements, and rarely explore logic between solutions and problem causes. There was a significant relationship between belief type and the likelihood that leaders will test the validity of those beliefs—beliefs about problem causes were the least likely to be tested. The patterns found here are likely to impact whether micro and mesosystem problems, and ultimately exo and macrosystem problems, are solved. Capability building in belief validity testing is vital for leadership professional learning to ensure curriculum, social justice and equity policy aspirations are realized in practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This study examines the extent to which leaders, in their conversations with others, test rather than assume the validity of their own and others’ beliefs about the nature, causes of, and solutions to problems of teaching and learning that arise in their sphere of responsibility. We define a problem as a gap between the current and desired state, plus the demand that the gap be reduced (Robinson, 1993). We position this focus within the broader context of educational change, and educational improvement in particular, since effective discussion of such problems is central to improvement and vital for addressing issues of educational equity and social justice.

Educational improvement and leaders’ role in problem solving

Educational leaders work in a discretionary problem-solving space. Ball (2018) describes discretionary spaces as the micro level practices of the teacher. It is imperative to attend to what happens in these spaces because the specific talk and actions that occur in particular moments (for example, what the teacher says or does when one student responds in a particular way to his or her question) impact all participants in the classroom and shape macro level educational issues including legacies of racism, oppression, and marginalization of particular groups of students. A parallel exists, we argue, for leaders’ problem solving—how capable leaders are at dealing with micro-level problems in the conversational moment impacts whether a school or network achieves its improvement goals. For example, how a leader deals with problems with a particular teacher or with a particular student or group of students is subtly but strongly related to the solving of equity problems at the exo and macro levels. Problem solving effectiveness is also related to challenges in the realization of curriculum reform aspirations, including curriculum reform depth, spread, reach, and pace (Sinnema & Stoll, 2020b).

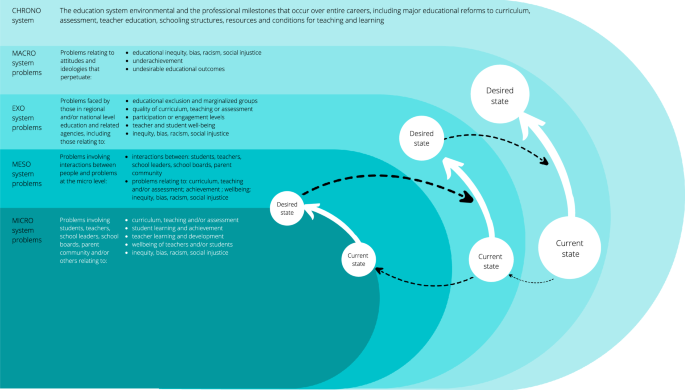

The conversations leaders have with others in their schools in their efforts to solve educational problems are situated in a broader environment which they both influence and are influenced by. We draw here on Bronfonbrenner’s (1992) ecological systems theory to construct a nested model of educational problem solving (see Fig. 1). Bronfenbrenner focused on the environment around children, and set out five interrelated systems that he professed influence a child’s development. We propose that these systems can also be used to understand another type of learner—educators, including leaders and teachers—in the context of educational problem solving.

Bronfenbrenner’s (1977) microsystem sets out the immediate environment, parents, siblings, teachers, and peers as influencers of and influenced by children. We propose the micro system for educators to include those they have direct contact with including their students, other teachers in their classroom and school, the school board, and the parent community. Bronfenbrenner’s meso system referred to the interactions between a child’s microsystems. In the same way, when foregrounding the ecological system around educators, we suggest attention to the problems that occur in the interactions between students, teachers, school leaders, their boards, and communities. In the exo system, Bronfenbrenner directs attention to other social structures (formal and informal), which do not themselves contain the child, but indirectly influence them as they affect one of the microsystems. In the same way, we suggest educational ministries, departments and agencies function to influence educators. The macro system as theorized by Bronfenbrenner focuses on how child development is influenced by cultural elements established in society, including prevalent beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions. In our model, we recognise how such cultural elements of Bronfenbrenner’s macro system also relate to educators in that dominant and pervasive beliefs, attitudes and perceptions create and perpetuate educational problems, including those relating to educational inequity, bias, racism, social injustice, and underachievement. The chronosystem, as Bronfenbrenner describes, shows the role of environmental changes across a lifetime, which influences development. In a similar way, educators′ professional transitions and professional milestones influence and are influenced by other system levels, and in the context of our work, their problem solving approaches.

Leaders’ effectiveness in discussions about problems related to the micro and mesosystem contributes greatly to the success of exosystem reform efforts, and those efforts, in turn, influence the beliefs, attitudes, and ideologies of the macrosystem. As Fig. 1 shows, improvement goals (indicated by the arrows moving from the current to a desired state) in the exo or macrosystem are unlikely to be achieved without associated improvement in the micro and mesosystem involving students, teachers, and groups of teachers, schools and their boards and parent communities. Similarly, the level of improvement in the macro and exosystems is limited by the extent to which more improvement goals at the micro and mesosystem are achieved through solving problems relating to students’ experience and school and classroom practices including curriculum, teaching, and assessment. As well as drawing on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, our nested model of problem solving draws on problem solving theory to draw attention to how gaps between current and desired states at each of the system levels also influence each other (Newell & Simon, 1972). Efforts to solve problems in any one system (to move from current state toward a more desired state) are supported by similar moves at other interrelated systems. For example, the success of a teacher seeking to solve a curriculum problem (demand from parents to focus on core knowledge in traditional learning domains, for example)—a problem related to the microsystem and mesosystem—will be influenced by how similar problems are recognised, attended to, and solved by those in the ministries, departments and agencies in the exosystem.

In considering the role of educational leaders in this nested model of problem solving, we take a capability perspective (Mumford et al., 2000) rather than a leadership style perspective (Bedell-Avers et al., 2008). School leaders (including those with formal and informal leadership positions) require particular capabilities if they are to enact ambitious policies and solve complex problems related to enhancing equity for marginalized and disadvantaged groups of students (Mavrogordato & White, 2020). Too often, micro and mesosystem problems remain unsolved which is problematic not only for those directly involved, but also for the resolution of the related exo and macrosystem problems. The ill-structured nature of the problems school leaders face, and the social nature of the problem-solving process, contribute to the ineffectiveness of leaders’ problem-solving efforts and the persistence of important microsystem and mesosystem problems in schools.

Ill-structured problems

The problems that leaders need to solve are typically ill-structured rather than clearly defined, complex rather that than straight-forward, and adaptive rather than routine challenges (Bedell-Avers et al., 2008; Heifetz et al., 2009; Leithwood & Stager, 1989; Leithwood & Steinbach, 1992, 1995; Mumford & Connelly, 1991; Mumford et al., 2000; Zaccaro et al., 2000). As Mumford and Connelly explain, “even if their problems are not totally unprecedented, leaders are, […] likely to be grappling with unique problems for which there is no clear-cut predefined solution” (Mumford & Connelly, 1991, p. 294). Most such problems are difficult to solve because they can be construed in various ways and lack clear criteria for what counts as a good solution. Mumford et al. (2000) highlight the particular difficulties in solving ill-structured problems with regard to accessing, evaluating and using relevant information:

Not only is it difficult in many organizational settings for leaders to say exactly what the problem is, it may not be clear exactly what information should be brought to bear on the problem. There is a plethora of available information in complex organizational systems, only some of which is relevant to the problem. Further, it may be difficult to obtain accurate, timely information and identify key diagnostic information. As a result, leaders must actively seek and carefully evaluate information bearing on potential problems and goal attainment. (p. 14)

Problems in schools are complex. Each single problem can comprise multiple educational dimensions (learners, learning, curriculum, teaching, assessment) as well as relational, organizational, psychological, social, cultural, and political dimensions. In response to a teaching problem, for example, a single right or wrong answer is almost never at play; there are typically countless possible ‘responses’ to the problem of how to teach effectively in any given situation.

Problem solving as socially situated

Educational leaders’ problem solving is typically social because multiple people are usually involved in defining, explaining, and solving any given problem (Mumford et al., 2000). When there are multiple parties invested in addressing a problem, they typically hold diverse perspectives on how to describe (frame, perceive, and communicate about problems), explain (identify causes which lead to the problem), and solve the problem. Argyris and Schön (1974) argue that effective leaders must manage the complexity of integrating multiple and diverse perspectives, not only because all parties need to be internally committed to solutions, but also because quality solutions rely on a wide range of perspectives and evidence. Somewhat paradoxically, while the multiple perspectives involved in social problem solving add to their inherent complexity, these perspectives are a resource for educational change, and for the development of more effective solutions (Argyris & Schön, 1974). The social nature of problem solving requires high trust so participants can provide relevant, accurate, and timely information (rather than distort or withhold it), recognize their interdependence, and avoid controlling others. In high trust relationships, as Zand’s early work in this field established, “there is less socially generated uncertainty and problems are solved more effectively” (Zand, 1972, p. 238).

Leaders’ capabilities in problem solving

Leadership research has established the centrality of capability in problem solving to leadership effectiveness generally (Marcy & Mumford, 2010; Mumford et al., 2000, 2007) and to educational leadership in particular. Leithwood and Stager (1989), for example, consider “administrator’s problem-solving processes as crucial to an understanding of why principals act as they do and why some principals are more effective than others” (p. 127). Similarly, Robinson (1995, 2001, 2010) positions the ability to solve complex problems as central to all other dimensions of effective educational leadership. Unsurprisingly, problem solving is often prominent in standards for school leaders/leadership and is included in tools for the assessment of school leadership (Goldring et al., 2009). Furthermore, its importance is heightened given the increasing demand and complexity in standards for teaching (Sinnema, Meyer & Aitken, 2016) and the trend toward leadership across networks of schools (Sinnema, Daly, Liou, & Rodway, 2020a) and the added complexity of such problem solving where a system perspective is necessary.

Empirical research on leaders’ practice has revealed that there is a need for capability building in problem solving (Le Fevre et al., 2015; Robinson et al., 2020; Sinnema et al., 2013; Sinnema et al., 2016; Smith, 1997; Spillane et al., 2009; Timperley & Robinson, 1998; Zaccaro et al., 2000). Some studies have compared the capability of leaders with varying experience. For example, Leithwood and Stager (1989) noted differences in problem solving approaches between novice and expert principals when responding to problem scenarios, particularly when the scenarios described ill-structured problems. Principals classified as ‘experts’ were more likely to collect information rather than make assumptions, and perceived unstructured problems to be manageable, whereas typical principals found these problems stressful. Expert principals also consulted extensively to get relevant information and find ways to deal with constraints. In contrast, novice principals consulted less frequently and tended to see constraints as obstacles (Leithwood & Stager, 1989). Allison and Allison (1993) reported that while experienced principals were better than novices at developing abstract problem-solving goals, they were less interested in the detail of how they would pursue these goals. Similar differences were found in Spillane et al.’s (2009) work that found expert principals to be better at interpreting problems and reflecting on their own actions compared with aspiring principals. More recent work (Sinnema et al., 2021) highlights that educators perceptions of discussion quality is positively associated with both new learning for the educator (learning that influences their practice) and improved practice (practices that reach students)—the more robust and helpful educators report their professional discussion to be, the more likely they are to report improvement in their practice. This supports the demand for quality conversation in educational teams.

Solving problems related to teaching and learning that occur in the micro or mesosystem usually requires conversations that demand high levels of interpersonal skill. Skill development is important because leaders tend to have difficulty inquiring deeply into the viewpoints of others (Le Fevre & Robinson, 2015; Le Fevre et al., 2015; Robinson & Le Fevre, 2011). In a close analysis of 43 conversation transcripts, Le Fevre et al. (2015) showed that when leaders anticipated or encountered diverse views, they tended to ask leading or loaded rather than genuine questions. This pattern was explained by their judgmental thinking, and their desire to avoid negative emotion and stay in control of the conversation. In a related study of leaders’ conversations, a considerable difference was found between the way educational leaders described their problem before and during the conversation with those involved (Sinnema et al., 2013). Prior to the conversation, privately, they tended to describe their problem as more serious and more urgent than they did in the conversation they held later with the person concerned.

One of the reasons for the mismatch between their private descriptions and public disclosures was the judgmental framing of their beliefs about the other party’s intentions, attitudes, and/or motivations (Peeters & Robinson, 2015). If leaders are not willing or able to reframe such privately-held beliefs in a more respectful manner, they will avoid addressing problems through fear of provoking negative emotion, and neither party will be able to critique the reasoning that leads to the belief in question (Robinson et al., 2020). When that happens, beliefs based on faulty reasoning may prevail, problem solutions may be based only on that which is discussable, and the problem may persist.

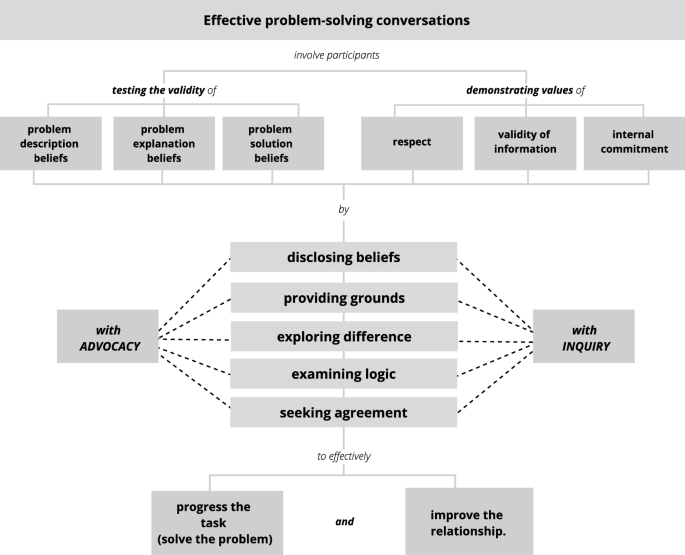

A model of effective problem-solving conversations

We present below a normative model of effective problem-solving conversations (Fig. 2) in which testing the validity of relevant beliefs plays a central role. Leaders test their beliefs about a problem when they draw on a set of validity testing behaviors and enact those behaviors, through their inquiry and advocacy, in ways that are consistent with the three interpersonal values included in the model. The model proposes that these processes increase the effectiveness of social problem solving, with effectiveness understood as progressing the task of solving the problem while maintaining or improving the leader’s relationship with those involved. In formulating this model, we drew on the previously discussed research on problem solving and theories of interpersonal and organisational effectiveness.

The role of beliefs in problem solving

Beliefs are important in the context of problem solving because they shape decisions about what constitutes a problem and how it can be explained and resolved. Beliefs link the object of the belief (e.g., a teacher’s planning) to some attribute (e.g., copied from the internet). In the context of school problems these attributes are usually tightly linked to a negative evaluation of the object of the belief (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Problem solving, therefore, requires explicit attention by leaders to the validity of the information on which their own and others’ beliefs are based. The model draws on the work of Mumford et al. (2000) by highlighting three types of beliefs that are central to how people solve problems—beliefs about whether and why a situation is problematic (we refer to these as problem description beliefs); beliefs about the precursors of the problem situation (we refer to these as problem explanation beliefs); and beliefs about strategies which could, would, or should improve the situation (we refer to these as problem solution beliefs). With regard to problem explanation beliefs, it is important that attention is not limited to surface level factors, but also encompasses consideration of deeper related issues in the broader social context and how they contribute to any given problem.

The role of values in problem-solving conversations

Figure 2 proposes that problem solving effectiveness is increased when leaders’ validity testing behaviors are consistent with three values—respecting the views of others, seeking to maximize validity of their own and others’ beliefs, and building internal commitment to decisions reached. The inclusion of these three values in the model means that our validity testing behaviors must be conceptualized and measured in ways that capture their interpersonal (respect and internal commitment) and epistemic (valid information) underpinnings. Without this conceptual underpinning, it is likely to be difficult to identify the validity testing behaviors that are associated with effectiveness. For example, the act of seeking agreement can be done in a coercive or a respectful manner, so it is important to define and measure this behavior in ways that distinguish between the two. How this and similar distinctions were accomplished is described in the subsequent section on the five validity testing behaviors.

The three values in Fig. 2 are based on the theories and practice of interpersonal and organizational effectiveness developed by Argyris and Schön (1974, 1978, 1996) and applied more recently in a range of educational leadership research contexts (Hannah et al., 2018; Patuawa et al., 2021; Sinnema et al., 2021a). We have drawn on the work of Argyris and Schön because their theories explain the dilemma many leaders experience between the two components of problem solving effectiveness and indicate how that dilemma can be avoided or resolved.

Seeking to maximize the validity of information is important because leaders’ beliefs have powerful consequences for the lives and learning of teachers and students and can limit or support educational change efforts. Leaders who behave consistently with the validity of information value are truth seekers rather than truth claimers in that they are open-minded and thus more attentive to the information that disconfirms rather than confirms their beliefs. Rather than assuming the validity of their beliefs and trying to impose them on others, their stance is one of seeking to detect and correct errors in their own and others′ thinking (Robinson, 2017).

The value of respect is closely linked to the value of maximizing the validity of information. Leaders increase validity by listening carefully to the views of others, especially if those views differ from their own. Listening carefully requires the accordance of worth and respect, rather than private or public dismissal of views that diverge from or challenge one’s own. If leaders’ conversations are guided by the two values of valid information and respect, then the third value of fostering internal commitment is also likely to be present. Teachers become internally committed to courses of action when their concerns have been listened to and directly addressed as part of the problem-solving process.

The role of validity testing behaviors in problem solving

Figure 2 includes five behaviors designed to test the validity of the three types of belief involved in problem solving. They are: 1) disclosing beliefs; 2) providing grounds; 3) exploring difference; 4) examining logic; and 5) seeking agreement. These behaviors enable leaders to check the validity of their beliefs by engaging in open minded disclosure and discussion of their thinking. While these behaviors are most closely linked to the value of maximizing valid information, the values of respect and internal commitment are also involved in these behaviors. For example, it is respectful to honestly and clearly disclose one’s beliefs about a problem to the other person concerned (advocacy), and to do so in ways that make the grounds for the belief testable and open to revision. It is also respectful to combine advocacy of one’s own beliefs with inquiry into others’ reactions to those beliefs and with inquiry into their own beliefs. When leaders encounter doubts and disagreements, they build internal rather than external commitment by being open minded and genuinely interested in understanding the grounds for them (Spiegel, 2012). By listening to and responding directly to others’ concerns, they build internal commitment to the process and outcomes of the problem solving.

Advocacy and inquiry dimensions

Each of the five validity testing behaviors can take the form of a statement (advocacy) or a question (inquiry). A leader’s advocacy contributes to problem solving effectiveness when it communicates his or her beliefs and the grounds for them, in a manner that is consistent with the three values. Such disclosure enables others to understand and critically evaluate the leader’s thinking (Tompkins, 2013). Respectful inquiry is equally important, as it invites the other person into the conversation, builds the trust they need for frank disclosure of their views, and signals that diverse views are welcomed. Explicit inquiry for others’ views is particularly important when there is a power imbalance between the parties, and when silence suggests that some are reluctant to disclose their views. Across their careers, leaders tend to rely more heavily on advocating their own views than on genuinely inquiring into the views of others (Robinson & Le Fevre, 2011). It is the combination of advocacy and inquiry behaviors, that enables all parties to collaborate in formulating a more valid understanding of the nature of the problem and of how it may be solved.

The five validity testing behaviors

Disclosing beliefs is the first and most essential validity testing behavior because beliefs cannot be publicly tested, using the subsequent four behaviors, if they are not disclosed. This behavior includes leaders’ advocacy of their own beliefs and their inquiry into others’ beliefs, including reactions to their own beliefs (Peeters & Robinson, 2015; Robinson & Le Fevre, 2011).

Honest and respectful disclosure ensures that all the information that is believed to be relevant to the problem, including that which might trigger an emotional reaction, is shared and available for validity testing (Robinson & Le Fevre, 2011; Robinson et al., 2020; Tjosvold et al., 2005). Respectful disclosure has been linked with follower trust. The empirical work of Norman et al. (2010), for example, showed that leaders who disclose more, and are more transparent in their communication, instill higher levels of trust in those they work with.

Providing grounds, the second validity testing behavior, is concerned with leaders expressing their beliefs in a way that makes the reasoning that led to them testable (advocacy) and invites others to do the same (inquiry). When leaders clearly explain the grounds for their beliefs and invite the other party to critique their relevance or accuracy, the validity or otherwise of the belief becomes more apparent. Both advocacy and inquiry about the grounds for beliefs can lead to a strengthening, revision, or abandonment of the beliefs for either or both parties (Myran & Sutherland, 2016; Robinson & Le Fevre, 2011; Robinson et al., 2020).

Exploring difference is the third validity testing behavior. It is essential because two parties simply disclosing beliefs and the grounds for them is insufficient for arriving at a joint solution, particularly when such disclosure reveals that there are differences in beliefs about the accuracy and implications of the evidence or differences about the soundness of arguments. Exploring difference through advocacy is seen in such behaviors as identifying and signaling differing beliefs and evaluating contrary evidence that underpins those differing beliefs. An inquiry approach to exploring difference (Timperley & Parr, 2005) occurs when a leader inquires into the other party’s beliefs about difference, or their response to the leaders’ beliefs about difference.

Exploring differences in beliefs is key to increasing validity in problem solving efforts (Mumford et al., 2007; Robinson & Le Fevre, 2011; Tjosvold et al., 2005) because it can lead to more integrative solutions and enhance the commitment from both parties to work with each other in the future (Tjosvold et al., 2005). Leaders who are able to engage with diverse beliefs are more likely to detect and challenge any faulty reasoning and consequently improve solution development (Le Fevre & Robinson, 2015). In contrast, when leaders do not engage with different beliefs, either by not recognizing or by intentionally ignoring them, validity testing is more limited. Such disengagement may be the result of negative attributions about the other person, such as that they are resistant, stubborn, or lazy. Such attributions reduce opportunities for the rigorous public testing that is afforded by the exchange and critical examination of competing views.

Examining logic, the fourth validity testing behavior, highlights the importance of devising a solution that adequately addresses the nature of the problem at hand and its causes. To develop an effective solution both parties must be able to evaluate the logic that links problems to their assumed causes and solutions. This behavior is present when the leader suggests or critiques the relationship between possible causes of and solutions to the identified problem. In its inquiry form, the leader seeks such information from the other party. As Zaccaro et al. (2000) explain, good problem solvers have skills and expertise in selecting the information to attend to in their effort to “understand the parameters of problems and therefore the dimensions and characteristics of a likely solution” (p. 44–45). These characteristics may include solution timeframes, resource capacities, an emphasis on organizational versus personal goals, and navigation of the degree of risk allowed by the problem approach. Explicitly exploring beliefs is key to ensuring the logic linking problem causes and any proposed solution. Taking account of a potentially complex set of contributing factors when crafting logical solutions, and testing the validity of beliefs about them, is likely to support effective problem solving. This requires what Copland (2010) describes as a creative process with similarities to clinical reasoning in medicine, in which “the initial framing of the problem is fundamental to the development of a useful solution” (p. 587).

Seeking agreement, the fifth validity testing behavior, signals the importance of warranted agreement about problem beliefs. We use the term ‘warranted’ to make clear that the goal is not merely getting the other party to agree (either that something is a problem, that a particular cause is involved, or that particular actions should be carried out to solve it)—mere agreement is insufficient. Rather, the goal is for warranted agreement whereby both parties have explored and critiqued the beliefs (and their grounds) of the other party in ways that provide a strong basis for the agreement. Both parties must come to some form of agreement on beliefs because successful solution implementation occurs in a social context, in that it relies on the commitment of all parties to carry it out (Mumford et al., 2000; Robinson & Le Fevre, 2011; Tjosvold et al., 2005). Where full agreement does not occur, the parties must at least be clear about where agreement/disagreement lies and why.

Testing the validity of beliefs using these five behaviors, and underpinned by the values described earlier is, we argue, necessary if conversations are to lead to two types of improvement—progress on the task (i.e., solving the problem) and improving the relationship between those involved in the conversation (i.e., ensuring those relationship between the problem-solvers is intact and enhanced through the process). We draw attention here to those improvement purposes as distinct from those underpinning work in the educational leadership field that takes a neo-managerialist perspective. The rise of neo-managerialism is argued to redefine school management and leadership along managerial lines and hence contribute to schools that are inequitable, reductionist, and inauthentic (Thrupp & Willmott, 2003). School leaders, when impacted by neo-managerialism, need to be (and are seen as) “self-interested, opportunistic innovators and risk-takers who exploit information and situations to produce radical change.” In contrast, the model we propose rejects self-interest. Our model emphasizes on deep respect for the views of others and the relentless pursuit of genuine shared commitment to understanding and solving problems that impact on children and young people through collaborative engagement in joint problem solving. Rather than permitting leaders to exploit others, our model requires leaders to be adept at using both inquiry and advocacy together with listening to both progress the task (solving problems) and simultaneously enhance the relationship between those involved. We position this model of social problem solving effectiveness as a tool for addressing social justice concerns—it intentionally dismisses problem solving approaches that privilege organizational efficiency indicators and ignore the wellbeing of learners and issues of inequity, racism, bias, and social injustice within and beyond educational contexts.

Methodology

The following section outlines the purpose of the study, the participants, and the mixed methods approach to data collection and analysis.

Research purpose

Our prior qualitative research (Robinson et al., 2020) involving in-depth case studies of three educational leaders revealed problematic patterns in leaders’ approach to problem-solving conversations: little disclosure of causal beliefs, little public testing of beliefs that might trigger negative emotions, and agreement on solutions that were misaligned with causal beliefs. The present investigation sought to understand if a quantitative methodological approach would reveal similar patterns and examine the relationship between belief types and leaders’ use of validity testing behaviors. Thus, our overarching research question was: to what extent do leaders test the validity of their beliefs in conversations with those directly involved in the analysis and resolution of the problem? Our argument is that while new experiences might motivate change in beliefs (Bonner et al., 2020), new insights gained through testing the validity of beliefs is also imperative to change. The sub-questions were:

-

1.

What is the relative frequency in the types of beliefs leaders hold about problems involving others?

-

2.

To what extent do leaders employ validity testing behaviors in conversations about those problems?

-

3.

Are there differential patterns in leaders’ validity testing of the different belief types?

Participants

The participants were 43 students in a graduate course on educational leadership in New Zealand who identified an important on the job problem that they intended to discuss with the person directly involved.

The mixed methods approach

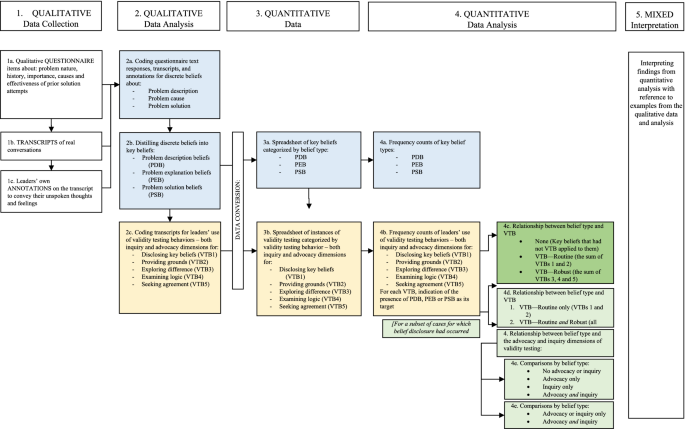

The study took a mixed methods approach using a partially mixed sequential equal status design; (QUAL → QUAN) (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2009). The five stages of sourcing and analyzing data and making interpretations are summarised in Fig. 3 below and outlined in more detail in the following sections (with reference in brackets to the numbered phases in the figure). We describe the study as partially mixed because, as Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2009 explain, in partially mixed methods “both the quantitative and qualitative elements are conducted either concurrently or sequentially in their entirety before being mixed at the data interpretation stage” (p. 267).

Stage 1: Qualitative data collection

Three data sources were used to reveal participants’ beliefs about the problem they were seeking to address. The first source was their response to nine open ended items in a questionnaire focused on a real problem the participant had attempted to address but that still required attention (1a). The items were about: the nature and history of the problem; its importance; their own and others’ contribution to it; the causes of the problem; and the approach to and effectiveness of prior attempts to resolve it.

The second source (1b) was the transcript of a real conversation (typically between 5 and 10 minutes duration) the leaders held with the other person involved in the problem, and the third was the leaders’ own annotations of their unspoken thoughts and feelings during the course of the conversation (1c). The transcription was placed in the right-hand column (RHC) of a split page with the annotations recorded at the appropriate place in the left-hand column (LHC). The LHC method was originally developed by Argyris and Schön (1974) as a way of examining discrepancies between people’s espoused and enacted interpersonal values. Referring to data about each leader’s behavior (as recorded in the transcript of the conversation) and their thoughts (as indicated in the LHC) was important since the model specifies validity testing behaviors that are motivated by the values of respect, valid information, and internal commitment. Since motives cannot be revealed by speech alone, we also needed access to the thoughts that drove their behavior, hence our use of the LHC data collection technique. This approach allowed us to respond to Leithwood and Stager’s (1989) criticism that much research on effective problem solving gives results that “reveal little or nothing about how actions were selected or created and treat the administrator’s mind as a ‘black box’” (p. 127).

Stage 2: Qualitative analysis

The three stages of qualitative analysis focused on identifying discrete beliefs in the three qualitative data sources, distilling those discrete beliefs into key beliefs, and identifying leaders’ use of validity testing behaviors.

Stage 2a: Analyzing types of beliefs about problems

For this stage, we developed and applied coding rules (see Table 1) for the identification of the three types of beliefs in the three sources described earlier—leaders’ questionnaire responses, conversation transcript (RHC), and unexpressed thoughts (LHC). We identified 903 discrete beliefs (utterances or thoughts) from the 43 transcripts, annotations, and questionnaires and recorded these on a spreadsheet (2a). While our model proposes that leaders’ inquiry will surface and test the beliefs of others, we quantify in this study only the leaders’ beliefs.

Stage 2b: Distilling discrete beliefs into key beliefs

Next, we distilled the 903 discrete beliefs into key beliefs (KBs) (2b). This was a complex process and involved multiple iterations across the research team to determine, check, and test the coding rules. The final set of rules for distilling key beliefs were:

-

1.

Beliefs should be made more succinct in the key belief statement, and key words should be retained as much as possible

-

2.

Judgment quality (i.e., negative or positive) of the belief needs to be retained in the key belief

-

3.

Key beliefs should use overarching terms where possible

-

4.

The meaning and the object of the belief need to stay constant in the key belief

-

5.

When reducing overlap, the key idea of both beliefs need to be captured in the key beliefs

-

6.

Distinctive beliefs need to be summarized on their own and not combined with other beliefs

-

7.

The subject of the belief must be retained in the key belief—own belief versus restated belief of other

-

8.

All belief statements must be accounted for in key beliefs

These rules were applied to the process of distilling multiple related beliefs into statements of key beliefs as illustrated by the example in the table below (Table 2).

Further examples of how the rules were applied are outlined in 'Appendix A'. The number of discrete beliefs for each leader ranged from 7 to 35, with an average of 21, and the number of key beliefs for each leader ranged between 4 and 14, with an average of eight key beliefs. Frequency counts were used to identify any patterns in the types of key beliefs which were held privately (not revealed in the conversation but signalled in the left hand column or questionnaire) or conveyed publicly (in conversation with the other party).

Stage 2c: Analyzing leaders’ use of validity testing behaviors

We then developed and applied coding rules for the five validity testing behaviors (VTB) outlined in our model (disclosing beliefs, providing grounds, exploring difference, examining logic, and seeking agreement). Separate rules were established for the inquiry and advocacy aspects of each VTB, generating ten coding rules in all (Table 3).

These rules, summarised in the table below, and outlined more fully in 'Appendix A', encompassed inclusion and exclusion criteria for the advocacy and inquiry dimensions of each validity testing behavior. For example, the inclusion rule for the VTB of ‘Disclosing Beliefs’ required leaders to disclose their beliefs about the nature, and/or causes, and/or possible solutions to the problem, in ways that were consistent with the three values included in the model. The associated exclusion rule signalled that this criterion was not met if, for example, the leader asked a question in order to steer the other person toward their own views without having ever disclosed their own views, or if they distorted the urgency or seriousness of the problem related to what they had expressed privately. The exclusion rules also noted how thoughts expressed in the left hand column would exclude the verbal utterance from being treated as disclosure—for example if there were contradictions between the right hand (spoken) and left hand column (thoughts), or if the thoughts indicated that the disclosure had been distorted in order to minimise negative emotion.

The coding rules reflected the values of respect and internal commitment in addition to the valid information value that was foregrounded in the analysis. The emphasis on inquiry, for example (into others’ beliefs and/or responses to the beliefs already expressed by the leader), recognised that internal commitment would be impossible if the other party held contrary views that had not been disclosed and discussed. Similarly, the focus on leaders advocating their beliefs, grounds for those beliefs and views about the logic linking solutions to problem causes recognise that it is respectful to make those transparent to another party rather than impose a solution in the absence of such disclosure.

The coding rules were applied to all 43 transcripts and the qualitative analysis was carried out using NVivo 10. A random sample of 10% of the utterances coded to a VTB category was checked independently by two members of the research team following the initial analysis by a third member. Any discrepancies in the coding were resolved, and data were recoded if needed. Descriptive analyses then enabled us to compare the frequency of leaders’ use of the five validity testing behaviors.

Stage 3: Data transformation: From qualitative to quantitative data

We carried out transformation of our data set (Burke et al., 2004), from qualitative to quantitative, to allow us to carry out statistical analysis to answer our research questions. The databases that resulted from our data transformation, with text from the qualitative coding along with numeric codes, are detailed next. In database 1, key beliefs were all entered as cases with indications in adjacent columns as to the belief type category they related to, and the source/s of the belief (questionnaire, transcript or unspoken thoughts/feelings). A unique identifier was created for each key belief.

In database 2, each utterance identified as meeting the VTB coding rules were entered in column 1. The broader context of the utterance from the original transcript was then examined to establish the type of belief (description, explanation, or solution) the VTB was being applied to, with this recorded numerically alongside the VTB utterance itself. For example, the following utterance had been coded to indicate that it met the ‘providing grounds’ coding rule, and in this phase it was also coded to indicate that it was in relation to a ‘problem description’ belief type:

“I noticed on the feedback form that a number of students, if I’ve got the numbers right here, um, seven out of ten students in your class said that you don’t normally start the lesson with a ‘Do Now’ or a starter activity.” (case 21)

A third database listed all of the unique identifiers for each leader’s key beliefs (KB) in the first column. Subsequent columns were set up for each of the 10 validity testing codes (the five validity testing behaviors for both inquiry and advocacy). The NVivo coding for the VTBs was then examined, one piece of coding at a time, to identify which key belief the utterance was associated with. Each cell that intersected the appropriate key belief and VTB was increased by one as a VTB utterance was associated with a key belief. Our database included variables for both the frequency of each VTB (the number of instances the behavior was used) and a parallel version with just a dichotomous variable indicating the presence or absence or each VTB. The dichotomous variable was used for our subsequent analysis because multiple utterances indicating a certain validity testing behavior were not deemed to necessarily constitute better quality belief validity testing than one utterance.

Stage 4: Quantitative analysis

The first phase of quantitative analysis involved the calculation of frequency counts for the three belief types (4a). Next, frequencies were calculated for the five validity testing behaviors, and for those behaviors in relation to each belief type (4b).

The final and most complex stage of the quantitative analysis, stages 4c through 4f, involved looking for patterns across the two sets of data created through the prior analyses (belief type and validity testing behaviors) to investigate whether leaders might be more inclined to use certain validity testing behaviors in conjunction with a particular belief type.

Stage 4a: Analyzing for relationships between belief type and VTB

We investigated the relationship between belief type and VTB, first, for all key beliefs. Given initial findings about variability in the frequency of the VTBs, we chose not to use all five VTBs separately in our analysis, but rather the three categories of: 1) None (key beliefs that had no VTB applied to them); 2) VTB—Routine (the sum of VTBs 1 and 2; given those were much more prevalent than others in the case of both advocacy and inquiry); and 3) VTB—Robust (the sum of the VTBs 3, 4 and 5 given these were all much less prevalent than VTBs 1 and 2, again including both advocacy and/or inquiry). Cross tabs were prepared and a chi-square test of independence was performed on the data from all 331 key beliefs.

Stage 4b: Analyzing for relationships between belief type and VTB

Next, because more than half (54.7%, 181) of the 331 key beliefs were not tested by leaders using any one of the VTBs, we analyzed a sub-set of the database, selecting only those key beliefs where leaders had disclosed the belief (using advocacy and/or inquiry). The reason for this was to ensure that any relationships established statistically were not unduly influenced by the data collection procedure which limited the time for the conversation to 10 minutes, during which it would not be feasible to fully disclose and address all key beliefs held by the leader. For this subset we prepared cross tabs and carried out chi-square tests of independence for the 145 key beliefs that leaders had disclosed. We again investigated the relationship between key belief type and VTBs, this time using a VTB variable with two categories: 1) More routine only and 2) More routine and robust.

Stage 4c: Analyzing for relationships between belief type and advocacy/inquiry dimensions of validity testing

Next, we investigated the relationship between key belief type and the advocacy and inquiry dimensions of validity testing. This analysis was to provide insight into whether leaders might be more or less inclined to use certain VTBs for certain types of belief. Specifically, we compared the frequency of utterances about beliefs of all three types for the categories of 1) No advocacy or inquiry, 2) Advocacy only, 3) Inquiry only, and 4) Advocacy and inquiry (4e). Cross tabs were prepared, and a chi-square test of independence was performed on the data from all 331 key beliefs. Finally, we again worked with the subset of 145 key beliefs that had been disclosed, comparing the frequency of utterances coded to 1) Advocacy or inquiry only, or 2) Both advocacy and inquiry (4f).

Results

Below, we highlight findings in relation to the research questions guiding our analysis about: the relative frequency in the types of beliefs leaders hold about problems involving others; the extent to which leaders employ validity testing behaviors in conversations about those problems; and differential patterns in leaders’ validity testing of the different belief types. We make our interpretations based on the statistical analysis and draw on insights from the qualitative analysis to illustrate those results.

Belief types

Leaders’ key beliefs about the problem were evenly distributed between the three belief types, suggesting that when they think about a problem, leaders think, though not necessarily in a systematic way, about the nature of, explanation for, and solutions to their problem (see Table 4). These numbers include beliefs that were communicated and also those recorded privately in the questionnaire or in writing on the conversation transcripts.

Patterns in validity testing

The majority of the 331 key beliefs (54.7%, 181) were not tested by leaders using any one of the VTBs, not even the behavior of disclosing the belief. Our analysis of the VTBs that leaders did use (see Table 5) shows the wide variation in frequency of use with some, arguably the more robust ones, hardly used at all.

The first pattern was more frequent disclosure of key beliefs than provision of the grounds for them. The lower levels of providing grounds is concerning because it has implications for the likelihood of those in the conversation subsequently reaching agreement and being able to develop solutions logically aligned to the problem (VTB4). The logical solution if it is the time that guided reading takes that is preventing a teacher doing ‘shared book reading’ (as Leader 20 believed to be the case) is quite different to the solution that is logical if in fact the reason is something different, for example uncertainty about how to go about ‘shared book reading’, lack of shared book resources, or a misunderstanding that school policy requires greater time on shared reading.

The second pattern was a tendency for leaders to advocate much more than they inquire— there was more than double the proportion of advocacy than inquiry overall and for some behaviors the difference between advocacy and inquiry was up to seven times greater. This suggests that leaders were more comfortable disclosing their own beliefs, providing the grounds for their own beliefs and expressing their own assumptions about agreement, and less comfortable in inquiring in ways that created space and invited the other person in the conversation to reveal their beliefs.

A third pattern revealed in this analysis was the difference in the ratio of inquiry to advocacy between VTB1 (disclosing beliefs)—a ratio of close to 1:2 and VTB2 (providing grounds)—a ratio of close to 1:7. Leaders are more likely to seek others’ reactions when they disclose their beliefs than when they give their grounds for those beliefs. This might suggest that leaders assume the validity of their own beliefs (and therefore do not see the need to inquire into grounds) or that they do not have the skills to share the grounds associated with the beliefs they hold.

Fourthly, there was an absence of attention to three of the VTBs outlined in our model—in only very few of the 329 validity testing utterances the 43 leaders used were they exploring difference (11 instances), examining logic (4 instances) or seeking agreement (22 instances). In Case 22, for example, the leader claimed that learning intentions should be displayed and understood by children and expressed concern that the teacher was not displaying them, and that her students thus did not understand the purpose of the activities they were doing. While the teacher signaled her disagreement with both of those claims—“I do learning intentions, it’s all in my modelling books I can show them to you if you want” and “I think the children know why they are learning what they are learning”—the fact that there were differences in their beliefs was not explicitly signaled, and the differences were not explored. The conversation went on, with each continuing to assume the accuracy of their own beliefs. They were unable to reach agreement on a solution to the problem because they had not established and explored the lack of agreement about the nature of the problem itself. We presume from these findings, and from our prior qualitative work in this field, that those VTBs are much more difficult, and therefore much less likely to be used than the behaviors of disclosing beliefs and providing grounds.

The relationship between belief type and validity testing behaviors

The relationship between belief type and category of validity testing behavior was significant (Χ2(4) = 61.96, p < 0.001). It was notable that problem explanation beliefs were far less likely than problem description or problem solution beliefs to be subject to any validity testing (the validity of more than 80% of PEBs was not tested) and, when they were tested, it was typically with the more routine rather than robust VTBs (see Table 6).

Problem explanation beliefs were also most likely to not be tested at all; more than 80% of the problem explanation beliefs were not the focus of any validity testing. Further, problem description beliefs were less likely than problem solution beliefs to be the target of both routine and robust validity testing behaviors—12% of PDBs and 18% of PSBs were tested using both routine and robust VTBs.

Discussion

Two important assumptions underpin the study reported here. The first is that problems of equity must be solved, not only in the macrosystem and exosystem, but also as they occur in the day to day practices of leaders and teachers in micro and mesosystems. The second is that conversations are the key practice in which problem solving occurs in the micro and mesosystems, and that is why we focused on conversation quality. We focused on validity testing as an indicator of quality by closely analyzing transcripts of conversations between 43 individual leaders and a teacher they were discussing problems with.

Our findings suggest a considerable gap between our normative model of effective problem solving conversations and the practices of our sample of leaders. While beliefs about what problems are, and proposed solutions to them are shared relatively often, rarely is attention given to beliefs about the causes of problems. Further, while leaders do seem to be able to disclose and provide grounds for their beliefs about problems, they do so less often for beliefs about problem cause than other belief types. In addition, the critical validity testing behaviors of exploring difference, examining logic, and seeking agreement are very rare. Learning how to test the validity of beliefs is, therefore, a relevant focus for educational leaders’ goals (Bendikson et al., 2020; Meyer et al., 2019; Sinnema & Robinson, 2012) as well as a means for achieving other goals.

The patterns we found are problematic from the point of view of problem solving in schools generally but are particularly problematic from the point of view of macrosystem problems relating to equity. In New Zealand, for example, the underachievement and attendance issues of Pasifika students is a macrosystem problem that has been the target of many attempts to address through a range of policies and initiatives. Those efforts include a Pasifika Education Plan (Ministry of Education, 2013) and a cultural competencies framework for teachers of Pasifika learners—‘Tapasa’ (Ministry of Education, 2018) At the level of the mesosystem, many schools have strategic plans and school-wide programmes for interactions seeking to address those issues.

Resolving such equity issues demands that macro and exosystem initiatives are also reflected in the interactions of educators—hence our investigation of leaders’ problem-solving conversations and attention to whether leaders have the skills required to solve problems in conversations that contribute to aspirations in the exo and macrosystem, include of excellence and equity in new and demanding national curricula (Sinnema et al., 2020a; Sinnema, Stoll, 2020a). An example of an exosystem framework—the competencies framework for teachers of Pacific students in New Zealand—is useful here. It requires that teachers “establish and maintain collaborative and respectful relationships and professional behaviors that enhance learning and wellbeing for Pasifika learners” (Ministry of Education, 2018, p. 12). The success of this national framework is influenced by and also influences the success that leaders in school settings have at solving problems in the conversations they have about related micro and mesosystem problems.

To illustrate this point, we draw here on the example of one case from our sample that showed how problem-solving conversation capability is related to the success or otherwise of system level aspirations of this type. In the case of Leader 36, under-developed skill in problem solving talk likely stymied the success of the equity-focused system initiatives. Leader 36 had been alerted by the parents of a Pasifika student that their daughter “feels that she is being unfairly treated, picked on and being made to feel very uncomfortable in the teacher’s class.” In the conversation with Leader 36, the teacher described having established a good relationship with the student, but also having had a range of issues with her including that she was too talkative, that led the teacher to treat her in ways the teacher acknowledged could have made her feel picked on and consequently reluctant to come to school.

The teacher also told the leader that there were issues with uniform irregularities (which the teacher picked on) and general non conformity—“No, she doesn’t [conform]. She often comes with improper footwear, incorrect jacket, comes late to school, she puts make up on, there are quite a few things that aren’t going on correctly….”. The teacher suggested that the student was “drawing the wrong type of attention from me as a teacher, which has had a negative effect on her.” The teacher described to the leader a recent incident:

[The student] had come to class with her hair looking quite shabby so I quietly asked [the student] “Did you wake up late this morning?” and then she but I can’t remember, I made a comment like “it looks like you didn’t take too much interest in yourself.” To me, I thought there was nothing wrong with the comment as it did not happen publicly; it happened in class and I had walked up to her. Following that, [her] Mum sends another email about girls and image and [says] that I am picking on her again. I’m quite baffled as to what is happening here. (case 36)

This troubling example represented a critical discretionary moment. The pattern of belief validity testing identified through our analysis of this case (see Table 7), however, mirrors some of the patterns evident in the wider sample.

The leader, like the student’s parents, believed that the teacher had been offensive in her communication with the student and also that the relationship between the teacher and student would be negatively impacted as a result. These two problem description beliefs were disclosed by the leader during her conversation with the teacher. However, while her disclosure of her belief about the problem description involved both advocating the belief, and inquiring into the other’s perception of it, the provision of grounds for the belief involved advocacy only. She reported the basis of the concern (the email from the student’s parents about their daughter feeling unfairly treated, picked on, and uncomfortable in class) but did not explicitly inquire into the grounds. This may be explained in this case through the teacher offering her own account of the situation that matched the parent’s report. Leader 36 also disclosed in her conversation with the teacher, her problem solution key belief that they should hold a restorative meeting between the teacher, the student, and herself.

What Leader 36 did not disclose was her belief about the explanation for the problem—that the teacher did not adequately understand the student personally, or their culture. The problem explanation belief (KB4) that she did inquire into was one the teacher raised—suggesting that the student has “compliance issues” that led the teacher to respond negatively to the student’s communication style—and that the teacher agreed with. The leader did not use any of the more robust but important validity testing behaviors for any of the key beliefs they held, either about problem description, explanation or solutions. And most importantly, this conversation highlights how policies and initiatives developed by those in the macrosystem, aimed at addressing equity issues, can be thwarted through well-intentioned but ultimately unsuccessful efforts of educators as they operate in the micro and mesosystem in what we referred to earlier as a discretionary problem solving space. The teacher’s treatment of the Pasifika student in our example was in stark contrast to the respectful and strong relationships demanded by the exosystem policy, the framework for teachers of Pasifika students. Furthermore, while the leader recognized the problem, issues of culture were avoided—they were not skilled enough in disclosing and testing their beliefs in the course of the conversation to contribute to broader equity concerns. The skill gap resonates with the findings of much prior work in this field (Le Fevre et al., 2015; Robinson et al., 2020; Sinnema et al., 2013; Smith, 1997; Spillane et al., 2009; Timperley & Robinson, 1998; Zaccaro et al., 2000), and highlights the importance of leaders, and those working with them in leadership development efforts, to recognize the interactions between the eco-systems outlined in the nested model of problem solving detailed in Fig. 1.

The reluctance of Leader 36 to disclose and discuss her belief that the teacher misunderstands the student and her culture is important given the wider research evidence about the nature of the beliefs teachers may hold about indigenous and minority learners. The expectations teachers hold for these groups are typically lower and more negative than for white students (Gay, 2005; Meissel et al., 2017). In evidence from the New Zealand context, Turner et al. (2015), for example, found expectations to differ according to ethnicity with higher expectations for Asian and European students than for Māori and Pasifika students, even when controlling for achievement, due to troubling teacher beliefs about students’ home backgrounds, motivations, and aspirations. These are just the kind of beliefs that leaders must be able to confront in conversations with their teachers.

We use this example to illustrate both the interrelatedness of problems across the ecosystem, and the urgency of leadership development intervention in this area. Our normative model of effective problem solving conversations (Fig. 2), we suggest, provides a useful framework for the design of educational leadership intervention in this area. It shows how validity testing behaviors should embody both advocacy and inquiry and be used to explore not only perceptions of problem descriptions and solutions, but also problem causes. In this way, we hope to offer insights into how the dilemma between trust and accountability (Ehren et al., 2020) might be solved through increased interpersonal effectiveness. The combination of inquiry with advocacy also marks this approach out from neo-liberal approaches that emphasize leaders staying in control and predominantly advocating authoritarian perspectives of educational leadership. The interpersonal effectiveness theory that we draw on (Argyris & Schön, 1974) positions such unilateral control as ineffective, arguing for a mutual learning alternative. The work of problem solving is, we argue, joint work, requiring shared commitment and control.

Our findings also call for more research explicitly designed to investigate linkages between the systems. Case studies are needed, of macro and exosystem inequity problems backward mapped to initiatives and interactions that occur in schools related to those problems and initiatives. Such research could capture the complex ways in which power plays out “in relation to structural inequalities (of class, disability, ethnicity, gender, nationality, race, sexuality, and so forth)” and in relation to “more shifting and fluid inequalities that play out at the symbolic and cultural levels (for example, in ways that construct who “has” potential)” (Burke & Whitty, 2018, p. 274).

Leadership development in problem solving should be approached in ways that surface and test the validity of leaders’ beliefs, so that they similarly learn to surface and test others’ beliefs in their leadership work. That is important not only from a workforce development point of view, but also from a social justice point of view since leaders’ capabilities in this area are inextricably linked to the success of educational systems in tackling urgent equity concerns.

References

Allison, D., & Allison, P. (1993). Both ends of a telescope: Experience and expertise in principal problem solving. Educational Administration Quarterly, 29(3), 302–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161x93029003005

Argyris, C., Schön, D. (1974). Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. Jossey-Bass.

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective Addison-Wesley.

Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1996). Organizational learning II: Theory, method and practice. Addison-Wesley.

Ball, D. L. (2018). Just dreams and imperatives: the power of teaching in the struggle for public education. New York, NYC: Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association.

Bedell-Avers, E., Hunter, S., & Mumford, M. (2008). Conditions of problem-solving and the performance of charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders: A comparative experimental study. The Leadership Quarterly, 19, 89–106.

Bendikson, L., Broadwith, M., Zhu, T., & Meyer, F. (2020). Goal pursuit practices in high schools: hitting the target?. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(6), 713–728. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-01-2020-0020

Bonner, S. M., Diehl, K., & Trachtman, R. (2020). Teacher belief and agency development in bringing change to scale. Journal of Educational Change, 21(2), 363–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-019-09360-4

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta, Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues. Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531.

Burke Johnson, R., & Onwuegbuzie, A. (2004). Mixed methods research; a research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14–26.

Burke, P. J., & Whitty, G. (2018). Equity issues in teaching and teacher education. Peabody Journal of Education, 93(3), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2018.1449800

Copland, F. (2010). Causes of tension in post-observation feedback in pre-service teacher training: An alternative view. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 466–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.06.001

Ehren, M., Paterson, A., & Baxter, J. (2020). Accountability and Trust: Two sides of the same coin? Journal of Educational Change, 21(1), 183–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-019-09352-4

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief An Introduction to Theory and Research. Attitude, Intention and Behavior. Addison-Wesley.

Gay, G. (2005). Politics of multicultural teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 56(3), 221–228.

Goldring, E., Cravens, X., Murphy, J., Porter, A., Elliott, S., & Carson, B. (2009). The evaluation of principals: What and how do states and urban disrticts assess leadership? The Elementary School Journal, 110(1), 19–36.

Hannah, D., Sinnema, C., & Robinson. V. (2018). Theory of action accounts of problem-solving: How a Japanese school communicates student incidents to parents. Management in Education, 33(2), 62–69.https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020618783809.

Heifetz, R., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Harvard Business Press.

Le Fevre, D., & Robinson, V. M. J. (2015). The interpersonal challenges of instructional leadership: Principals’ effectiveness in conversations about performance issues. Educational Administration Quarterly, 51(1), 58–95.

Le Fevre, D., Robinson, V. M. J., & Sinnema, C. (2015). Genuine inquiry: Widely espoused yet rarely enacted. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 43(6), 883–899.

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2009). A typology of mixed methods research designs. Quality & Quantity, 43(2), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3

Leithwood, K., & Steinbach, R. (1995). Expert problem solving: Evidence from school and district leaders. State University of New York Press.

Leithwood, K., & Stager, M. (1989). Expertise in Principals’ Problem Solving. Educational Administration Quarterly, 25(2), 126–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161x89025002003

Leithwood, K., & Steinbach, R. (1992). Improving the problem solving expertise of school administrators. Education and Urban Society, 24(3), 317–345.

Marcy, R., & Mumford, M. (2010). Leader cognition: Improving leader performance through causal analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(1), 1–19.

Mavrogordato, M., & White, R. (2020). Leveraging policy implementation for social justice: How school leaders shape educational opportunity when implementing policy for English learners. Educational Administration Quarterly, 56(1), 3–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X18821364

Meissel, K., Meyer, F., Yao, E. S., & Rubie-Davies, C. (2017). Subjectivity of Teacher Judgments: Exploring student characteristics that influence teacher judgments of student ability. Teaching and Teacher Education, 65, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.021

Meyer, F., Sinnema, C., & Patuawa, J. (2019). Novice principals setting goals for school improvement in New Zealand. School Leadership & Management, 39(2), 198−221. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2018.1473358

Ministry of Education. (2013). Pasifika education plan 2013–2017 Retrieved 9 July from https://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Ministry/Strategies-and-policies/PEPImplementationPlan20132017V2.pdf

Ministry of Education. (2018). Tapasā cultural competencies framework for teachers of Pacific learners. Ministry of Education.

Mumford, M., & Connelly, M. (1991). Leaders as creators: Leaders performance and problem solving in ill-defined domains. Leadership Quarterly, 2(4), 289–315.

Mumford, M., Friedrich, T., Caughron, J., & Byrne, C. (2007). Leader cognition in real-world settings: How do leaders think about crises? The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 515–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.09.002

Mumford, M., Zaccaro, S., Harding, F., Jacobs, T., & Fleishman, E. (2000). Leadership skills for a changing world: Solving complex social problems. Leadership Quarterly, 11(1), 11–35.

Myran, S., & Sutherland, I. (2016). Problem posing in leadership education: using case study to foster more effective problem solving. Journal of Cases in Educational Leadership, 19(4), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555458916664763

Newell, A., & Simon. (1972). Human problem solving. Prentice-Hall.

Norman, S., Avolio, B., & Luthans, B. (2010). The impact of positivity and transparency on trust in leaders and their perceived effectiveness. The Leadership Quarterly, 21, 350–364.

Patuawa, J., Robinson, V., Sinnema, C., & Zhu, T. (2021). Addressing inequity and underachievement: Middle leaders’ effectiveness in problem solving. Leading and Managing, 27(1), 51–78. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.925220205986712

Peeters, A., & Robinson, V. M. J. (2015). A teacher educator learns how to learn from mistakes: Single and double-loop learning for facilitators of in-service teacher education. Studying Teacher Education, 11(3), 213–227.

Robinson, V. M. J., Meyer, F., Le Fevre, D., & Sinnema, C. (2020). The Quality of Leaders’ Problem-Solving Conversations: truth-seeking or truth-claiming? Leadership and Policy in Schools, 1–22.

Robinson, V. M. J. (1993). Problem-based methodology: Research for the improvement of practice. Pergamon Press.

Robinson, V. M. J. (1995). Organisational learning as organisational problem-solving. Leading & Managing, 1(1), 63–78.

Robinson, V. M. J. (2001). Organizational learning, organizational problem solving and models of mind. In K. Leithwood & P. Hallinger (Eds.), Second international handbook of educational leadership and administration. Kluwer Academic.

Robinson, V. M. J. (2010). From instructional leadership to leadership capabilities: Empirical findings and methodological challenges. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 9(1), 1–26.

Robinson, V. M. J. (2017). Reduce change to increase improvement. Corwin Press.

Robinson, V. M. J., & Le Fevre, D. (2011). Principals’ capability in challenging conversations: The case of parental complaints. Journal of Educational Administration, 49(3), 227–255. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231111129046

Sinnema, C., Robinson, V. (2012). Goal setting in principal evaluation: Goal quality and predictors of achievement. Leadership and Policy in schools. 11(2), 135–167, https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2011.629767

Sinnema, C., Le Fevre, D., Robinson, V. M. J., & Pope, D. (2013). When others’ performance just isn’t good enough: Educational leaders’ framing of concerns in private and public. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 12(4), 301–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2013.857419

Sinnema, C., Ludlow, L. H., & Robinson, V. M. J. (2016a). Educational leadership effectiveness: A rasch analysis. Journal of Educational Administration, 54(3), 305–339. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-12-2014-0140

Sinnema, C., Meyer, F., & Aitken, G. (2016b). Capturing the complex, situated, and sctive nature of teaching through inquiry-oriented standards for teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116668017

Sinnema, C., Daly, A. J., Liou, Y.-h Sinnema, C., Daly, A. J., Liou, Y.-H., & Rodway, J. (2020a). Exploring the communities of learning policy in New Zealand using social network analysis: A case study of leadership, expertise, and networks. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.10.002

Sinnema, C., & Stoll, L. (2020b). Learning for and realising curriculum aspirations through schools as learning organisations. European Journal of Education, 55, 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12381

Sinnema, C., Nieveen, N., & Priestley, M. (2020c). Successful futures, successful curriculum: What can Wales learn from international curriculum reforms? The Curriculum Journal. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.17

Sinnema, C., Hannah, D., Finnerty, A., & Daly, A. J. (2021a). A theory of action account of within and across school collaboration: The role of relational trust in collaboration actions and impacts. Journal of Educational Change.

Sinnema, C., Hannah, D., Finnerty, A. et al. (2021b). A theory of action account of an across-school collaboration policy in practice. Journal of Educational Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09408-w

Sinnema, C., Liou, Y.-H., Daly, A., Cann, R., & Rodway, J. (2021c). When seekers reap rewards and providers pay a price: The role of relationships and discussion in improving practice in a community of learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 107, 103474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103474

Smith, G. (1997). Managerial problem solving: A problem-centered approach. In C. E. Zsambok & G. Klein (Eds.), Naturalistic Decision Making (pp. 371–380). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Spiegel, J. (2012). Open-mindedness and intellectual humility. School Field, 10(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878512437472

Spillane, J., Weitz White, K., & Stephan, J. (2009). School principal expertise: Putting expert aspiring principal differences in problem solving to the test. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 8, 128–151.

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2006). A general typology of research designs featuring mixed methods. Research in the Schools, 13, 12–28.

Thrupp, M., & Willmott, R. (2003). Education management in managerialist times: Beyond the textual apologists. Open University Press.

Timperley, H., & Parr, J. M. (2005). Theory competition and the process of change. Journal of Educational Change, 6(3), 227–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-005-5065-3

Timperley, H. S., & Robinson, V. M. J. (1998). Collegiality in schools: Its nature and implications for problem solving. Educational Administration Quarterly, 34(1), 608–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X980341003

Tjosvold, D., Sun, H., & Wan, P. (2005). Effects of openness, problem solving, and blaming on learning: An experiment in China. The Journal of Social Psychology, 145(6), 629–644. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.145.6.629-644

Tompkins, T. (2013). Groupthink and the Ladder of Inference : Increasing Effective Decision Making. The Journal of Human Resource and Adult Learning, 8(2), 84–90.

Turner, H., Rubie-Davies, C. M., & Webber, M. (2015). Teacher expectations, ethnicity and the achievement gap. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 50(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-015-0004-1

Zaccaro, S., Mumford, M., Connelly, M., Marks, M., & Gilbert, J. (2000). Assessment of leader problem-solving capabilities. Leadership Quarterly, 11(1), 37–64.

Zand, D. (1972). Trust and managerial problem solving. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17, 229–239.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions