Abstract

Lalo Yi presents a distribution of numeral-classifier pairs that appears to be the complete inverse of the norm found in other numeral-classifier languages. With many numerically-quantified, discourse-new referents, Lalo Yi permits only the use of a floated pattern, and it is not possible to combine numerals and classifiers with NPs as in other numeral-classifier languages. This patterning presents a clear challenge to the oft-adopted assumption that floating quantifiers are derived from non-floated forms by applications of movement (stranding), and potentially favors a base-generation/adverbial approach. A broader consideration of Lalo Yi, however, leads to the proposal that the occurrence of the floating pattern results from a combination of two occurrences of movement—DP movement to a low focus position/FocP, followed by NP-raising to a higher case position. Obligatory stranding of the DP remnant containing numeral-classifier pairs is suggested to result from the FocP being a (low) criterial position in the sense of Rizzi (in: Cheng and Corver (eds) Wh-movement: moving on, MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 97–134, 2006), requiring freezing-realization of the DP in SpecFocP but permitting sub-extraction of NP to satisfy case requirements licensed by a higher functional head. Quite generally, it is suggested that the paradigm in Lalo Yi demonstrates the grammaticalization of an optional tendency found elsewhere in numeral-classifier languages to use special forms for the specific and non-specific indefinite interpretations of numerically-quantified nominals. Additionally, the paper contributes to the growing description and typology of low focus phenomena across languages and observations of variation in the ways that focus may be realized in different languages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Studies of the phenomenon of floating quantifiers have regularly examined the relations between floated and non-floated patterns such as (1) and (2), highlighting connections and potential dissimilarities that may either support or argue against a transformational derivation of the former from the latter—a stranding/movement or base-generation analysis of floating quantifiers (Bobaljik 2003; Dowty and Brodie 1984; Sportiche 1988; Miyagawa 1989; McCloskey 2000; Fitzpatrick 2006; Ko 2007 among many others).

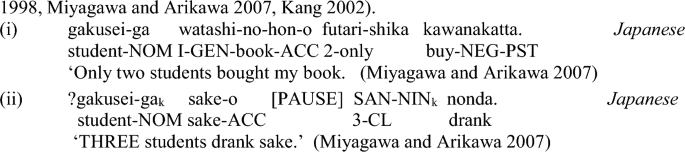

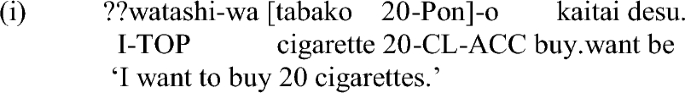

In a large body of work on floating quantifiers in numeral-classifier languages such as Japanese and Korean, researchers have motivated either stranding or base-generation ‘adverbial’ analyses of floating quantifiers on the basis of a range of patterns—most frequently observations of subject-object and argument versus non-argument asymmetries in the availability of floating quantifiers, differing properties of telicity in floated versus non-floated forms, and distributivity requirements associated with floated quantifiers but not corresponding non-floated forms—see Nakanishi (2008) for an excellent overview. The present paper probes an interaction that has not been considered prominently in previous investigations of floating quantifiers—that between specificity and the licensing of floated versus non-floated patterns, along with effects of focus. The consideration of such properties arises in the attempt to address a puzzle posed by patterns found in Lalo Yi (Tibeto-Burman) that presents an extremely unusual distribution of its numeral quantifiers and an entirely opposite patterning to the common distribution of such elements in other numeral-classifier languages.Footnote 1 Typically (Aikhenvald 2003; Bisang 1999; Jenks 2013a), in numeral-classifier languages, it is found that numerals and classifiers are combined with nouns to produce simple equivalents to forms such as ‘two students’, ‘three books’ etc. in non-classifier languages, and there may also be a less-commonly used option for numeral-classifier pairings to occur separated from the noun/NP in some other clause-internal position as floated quantifiers, as schematized in (3) and illustrated in (2a/b).Footnote 2 The noun-adjacent, single constituent merging of numerals and classifiers with nouns (3a) is therefore basic (i.e. common, neutral, and very frequent in use) and may be supplemented by a floating pattern (3b) (though not in all numeral-classifier languages—for example, the floating numeral-classifier variant does not occur in languages such as Vietnamese).

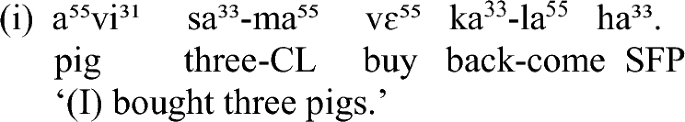

Lalo Yi interestingly shows a patterning that appears to be the complete inverse of the norm found in other numeral-classifier languages. In regular instances of speakers assertion of the existence of numerically-quantified new referents, equivalent to Japanese (2), Lalo Yi permits only the use of a floated (numeral-classifier) pattern (3b), and it is not possible to combine numerals and classifiers with NPs as in (3a) and in all other numeral-classifier languages (Liu and Bu 2018; Li and Bu 2021). The unavailability of combinations of numerals and classifiers with nouns/NPs in such cases presents a clear challenge to the oft-adopted assumption that floating quantifiers are derived from non-floated forms by applications of movement (stranding), and potentially favors a base-generation/adverbial approach. A broader consideration of Lalo Yi will, however, lead to the proposal that the occurrence of the floating pattern (3b) can better be compared with the obligatory stranding of elements such as prepositions and particles in other movement constructions (e.g. p-stranding in languages such as English), and results from the fully regular movement of NPs away from the numeral-classifier pairs they are originally merged with—i.e. the systematic conversion of a base form (3a) into the floating pattern (3b) found in surface sequences.

The motivation for a stranding analysis of Lalo Yi comes from a finer examination of numerically-quantified indefinites in the language. The paper will show that Lalo Yi has developed explicit, distinctive means to represent three different, common interpretations of indefinites, and obligatory stranding (quantifier float) is the signature pattern of one construal type—that of non-specific indefinites whose existence is asserted by speakers, in contrast with specific and non-referential non-specific indefinites that have different overt forms. The analysis argued for will attribute the floating quantifier pattern to a combination of two occurrences of movement—DP movement of [NP Num CL] constituents to a low focus position/FocP, followed by NP-raising to a higher case position. Obligatory stranding of the DP remnant containing the numeral-classifier pair is suggested to result from the FocP being a (low) criterial position in the sense of Rizzi (2006), requiring freezing-realization of the DP in SpecFocP but permitting sub-extraction of NP to satisfy case requirements licensed by a higher functional head. Quite generally, it is suggested that the paradigm in Lalo Yi demonstrates the grammaticalization of an optional tendency found elsewhere in numeral-classifier languages to use special forms for the specific and non-specific indefinite interpretations of numerically-quantified nominals. Additionally, the paper contributes to the growing description and typology of low focus phenomena across languages and observations of variation in the ways that focus may be realized in different languages (for example, differences in the effects of mirative focus on movement across Romance languages, Cruschina 2021, and exhaustivity requirements of pre-verbal focus in Hungarian, Kiss 1998).

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 describes the key patterns from Lalo Yi relating to the distribution of numeral-classifiers and how these patterns connect directly to the interpretation of nominals. Section 3 develops arguments for a focus-based stranding analysis of floating quantifiers and shows how the analysis is able to capture a range of further restrictions on the use of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi, including an aspectual split in the licensing of such forms. Section 4 places the analysis and patterning of Lalo Yi in a cross-linguistic perspective and compares Lalo Yi with Japanese, highlighting similarities and differences relating to focus and (non-)specificity in floating quantifier constructions. Section 5 concludes the paper with a consideration of the broader issues raised by the analysis.

2 Numeral quantifiers in Lalo Yi: distribution and issues of interpretation

In numeral-classifier languages, it has long been observed that numerals, classifiers, and nouns regularly combine in various ways to form a single, nominal syntactic constituent, as illustrated in (4a–e) below (Aikhenvald 2003).

Such constituents will occur in subject, object, and oblique positions and frequently permit movement as syntactic units to other locations in a clause:

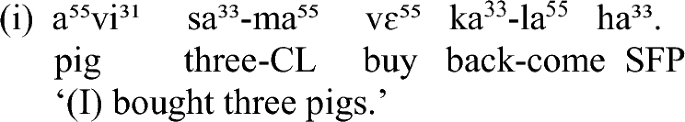

In the numeral-classifier language Lalo Yi, it is striking and unusual to find that patterns parallel to those in (5) and (6) are actually not possible—it is not possible to combine numeral-classifier pairs with nouns (in any order) to produce syntactic constituents that are interpreted as NPs/DPs whose existence is being asserted by a speaker. We will henceforth use the term ‘referentially-asserted indefinites’ to refer to such nominals, in order to distinguish these from two other interpretations of indefinite NPs/DPs—specific indefinites and other, non-specific indefinites that have no referential value, as discussed in Sect. 2.1. This restriction on referentially-asserted indefinites is shown in (7–8). For reasons that will soon become clear, we illustrate this with an [N Num CL] order. However, no linear ordering of these elements as parts of a single constituent is acceptable in (7–8), unlike other numeral-classifier languages, where it is fully common for numerals, classifiers, and nouns to occur in the positions of other non-numerically-quantified nominal phrases.

*[N Num CL] as object of the verb

In order for the intended meanings in examples such as (7–8) to be expressed, the numeral and classifier must occur separated from the noun/NP in a clause-final position before the verb, as schematized in (9) and illustrated in (10) and (11):

NP in subject position:

NP object separated from Num-CL:

Lalo Yi is thus found to impose a restrictive patterning in the potential use of its numeral quantifiers which, to the best of our knowledge, seems to be unattested in other languages. The puzzle posed by Lalo Yi is quite simply the following. Why does it not seem possible for numerals in Lalo Yi to be syntactically combined with nouns to create discourse-new, indefinite NPs/DPs equivalent to expressions such as ‘five students’ and ‘four books’ in other languages? In place of direct numerical quantification in such contexts, Lalo Yi requires the use of structures that resemble optional floating quantifier patterns in Japanese, Korean, Thai, and other numeral-classifier languages:

Such (floating) patterns have sometimes been analyzed as having an adverbial syntax, with the numeral-classifier pairing being merged separately from the NP (Nakanishi 2008; Kang 2002; Fukushima 1991; Ko 2007, 2014)—the ‘adverb’ analysis of floating quantifiers, as schematized in (13):

It might therefore be conjectured that Lalo Yi is a language that, uniquely, has only adverbial forms of numeral quantification, in this way perhaps providing useful support for the general, adverb approach to floating quantifiers. Here we will argue against such a conclusion, suggesting that a consideration of a fuller range of patterns in Lalo Yi leads more naturally to a different analysis, involving movement and the stranding of numeral quantifiers, in which numeral-classifier pairs are first directly merged with nouns and then derivationally separated. This approach to Lalo Yi will lead, in Section 4, to a reconsideration of floating quantifier patterns in languages such as Japanese and the issue of whether the factors identified as causing stranding in Lalo Yi may also be present and produce effects in other numeral-classifier languages.

2.1 Against a ban on merging numerals and classifiers with nouns in Lalo Yi

An ‘adverb analysis’ of floating numeral quantifiers positing that examples such as (10) and (11) can only arise via base-generation of numeral-classifier pairs in independent adverbial positions must assume that Lalo Yi, in contrast to other languages, has not developed a mechanism to build together numeral-classifiers and nouns/NP as a single syntactic constituent—hence that Merge is simply unavailable as an operation to assemble N, Num, and CL as subparts of a single nominal projection:

However, looking beyond indefinite NPs/DPs, it is found that numeral-classifier pairs actually can be syntactically combined with nouns/NPs in other structures in Lalo Yi. If a demonstrative is present in a DP, numerals and classifiers can be combined with nouns, in subject, object, and other positions in the patterning shown in (15) and illustrated in (16–18), as previously noted in Liu and Bu (2018) and Li and Bu (2021).

A further, novel observation is that numeral-classifier pairs can also be combined with nouns if the element nikhe occurs, an article whose use in Lalo Yi results in the interpretation of nominal phrases as specific indefinites (a patterning unnoticed in previous work on Lalo Yi):Footnote 3

The use of nikhe to communicate specificity in indefinite nominal phrases is shown in (20) and (21) below. If the speaker is familiar with the individual/entity referred to with an indefinite nominal, nikhe must be used:

By way of contrast, if the speaker is not familiar with an individual/entity whose existence is asserted, nikhe may not appear:

The article nikhe also occurs in instances of scopal specificity (wide scope relative to another quantifier as in (24)) and is obligatorily absent when an indefinite takes narrow scope (25):

The patterns in (16–18) with demonstratives and (20–21, 24) with the specific indefinite article nikhe, clearly indicate that numeral-classifier pairs can indeed be combined with nouns/NPs in larger nominal phrases/DPs. If a purely adverbial (separate merge) analysis were to be adopted to model the occurrence of floating quantifiers in examples like (10) and (11), in order to block the non-floating equivalents (7/8), such an approach would need to posit that Num and CL might only be merged with N(P) if an overt article (demonstrative, nikhe) is also present and the nominal phrase is built up to a DP level (so allowing for 16–18, 20–21). This, however, would certainly be a highly unusual syntactic rule/restriction, dictating that elements of a certain type X may only be merged with another constituent Y if a further element Z is also combined later in the derivation. A structure-building restriction of this hypothetical type requires lookahead in its application, does not have precedents from other constructions/languages to potentially justify its assumption, and would furthermore seem to rule out the regular combination of numeral-classifier pairs with nouns/NPs in other numeral-classifier languages.

There is also an additional, strong empirical reason to reject the assumption of a combinatorial restriction on the application of merge with numerals, classifiers, and nouns/NPs in Lalo Yi. Such combinations may in fact occur in the absence of any article (demonstrative, nikhe) in instances of non-referential non-specific indefinite interpretation—where the existence of an individual is not asserted. This is shown in (27) and (28).

The possibility for numerals and classifiers to merge with nouns/NPs in both specific (in/definite) and non-referential nominals suggests that there can be no general, structural ban on merging such elements together. The explanation of the required floating quantifier patterns in (10–11) should therefore not be attributed to such a hypothetical restriction (forcing the use of adverbial forms of numeral quantifiers) and arguably should be due to other factors. In what follows, we will make the assumption that numerals, classifiers, and nouns can indeed be freely merged together in all nominal structures, and that patterns such as (10–11) indicate separation and regular stranding of numeral-classifier pairs in instances of non-specific, referentially-asserted nominals, for reasons to be identified and discussed in Sect. 3. We will consequently motivate and develop a stranding analysis which can initially be schematized as in (29):

In closing this section, we will briefly summarize the observations that have been made here concerning nominal structures and their interpretation, highlighting the different ways that nominal phrases are realized in Lalo Yi and how such forms provide more explicit information about the intended construal of indefinites than is present in many languages. Cross-linguistically, nouns are regularly combined with numerals to result in a range of different interpretations—specific indefinite, non-specific referentially-asserted indefinite, and non-referential interpretations—and in English it is found that the same sequence of numeral + noun allows for all three interpretations:

In Lalo Yi, as described above, these different interpretations are necessarily encoded in different ways (adding representative example numbers):Footnote 4

Lalo Yi is consequently rich in the ways it distinguishes the meaning of indefinite nominals via different surface forms. In Sect. 3, we present our proposal for the derivation of non-specific, referentially-asserted indefinites and support for a focus-related stranding analysis.

3 A stranding analysis of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi

In pursuing a stranding approach to floating quantifier patterns in Lalo Yi, we will attempt to offer answers to the following questions:

-

How (syntactically) does the stranding of numeral quantifiers occur?

-

Why does stranding of numeral quantifiers take place?

-

To what extent and how is Lalo Yi different from other numeral-classifier languages in its patterns of floating quantifiers?

The analysis will also be guided by the need to account for four further properties of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi, described below in Sects. 3.1–3.4.

3.1 Property 1: Only one floating quantifier per clause

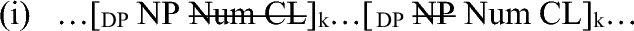

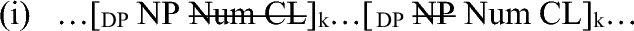

A clause may only contain one ‘floating’/syntactically independent numeral-classifier pair, and only one NP in each clause can be quantified by a clause-final numeral-classifier pair. No configuration is possible in Lalo Yi in which two nouns/NPs are each construed with a (floating) numeral-classifier pair, hence none of the crossing, nested, or non-crossing/nested configurations schematized in (32) and illustrated in (33) may occur—all are judged to be unacceptable/ungrammatical.

If a speaker wishes to mention more than one non-specific, referentially-asserted, numerically quantified NP, such elements must be split into two clauses:

This restriction on the multiple occurrences of floating numeral-classifier pairs with non-specific, referentially-asserted nominals is not present with specific DPs, where numerals and classifiers are directly combined with nouns/NPs inside DPs, and each DP may contain a numeral-classifier pair, as shown in (35):

The unacceptability of patterns such as (33a/b) is also not due to the occurrence of a subject-related floating quantifier following the object (a configuration which is frequently degraded/not possible in Japanese and Korean: Miyagawa 2017; Kang 2002). In Lalo Yi, it is elsewhere fully common and acceptable for subject-related floating quantifiers to follow objects:

An analysis of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi therefore needs to capture the observation that only one such element may occur per clause.

3.2 Property 2: Floating quantifiers occur in a fixed, low position in the clause

The position of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi is fully fixed, unlike the distribution of floating quantifiers in many other languages. In Lalo Yi, such elements must occur in an immediately pre-verbal position, and do not show the distribution of other adverbial types, which have some flexibility in their placement. This rigid pre-verbal positioning of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi is illustrated in (37). (37b) shows that even the non-specific objects of light verbs may not intervene between a floating quantifier and the verb:

It can also be noted that subjects and objects regularly move leftwards out of the vP, over low adverbs (whether subjects/objects are associated with a floating quantifier or not). This is illustrated in (38). Such movement can be assumed to be driven by case requirements relating to higher, vP-external functional heads, and applies to subjects and objects that are both definite and indefinite (specific and non-specific)—it is not restricted to just specific arguments (in (38) both subject and object are non-specific indefinites):

An analysis of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi consequently needs to capture the observation that the position of such elements is fixed and low in the clause, following arguments (subjects, objects) which have been raised out of the vP.

3.3 Property 3: Aspectual restrictions on the construal of floating quantifiers

If certain overt aspect markers (perfective, experiential, continuous aspect) occur on the verb, a clause-final numeral-classifier pair may be construed with the object of the verb, but never with a subject NP. This aspect-related restriction is schematized in (39b) and illustrated in (40a/b), (41) and (42).

Perfective aspect:

Continuous aspect::

Experiential aspect:

Other aspects/tense-forms (or the absence of any overt aspect-marking) regularly permit either subject or object to be construed with floating quantifiers. There is no parallel restriction on the construal of subjects with floating quantifiers when the verb has progressive aspect or future tense marking, as schematized in (43) and illustrated in (44) and (45):

Progressive aspect:

Future tense marking

An analysis of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi should capture the observation that the subject is structurally inaccessible to floating quantifier construal in certain aspectual forms.

3.4 Property 4: Floating quantifiers and focus

The occurrence of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi is regularly associated with two interpretational properties: (a) the assertion of existence of a non-specific, numerically-quantified referent (already noted), and (b) emphasis/focus—floating quantifiers are prosodically prominent (attract stress) and are often highlighted/offset by a preceding pause. Such elements also systematically occur immediately before the verb, where other focused material is regularly positioned, as in many other SOV languages, for example Turkish, Hindi, Bangla, Malayalam, Japanese, Korean, and Kartvelian among many others: Jayaseelan (2001), Erguvanı (1984), Kuno (1978), Kim (1988), Harris (1981). The occurrence of wh-elements and other focused phrases in immediate pre-verbal focus position is illustrated in (46–49) (resulting in conversion of the neutral SOV word order into OSV as the natural/automatic sequencing when the subject is focused/a wh-phrase):

Additionally, floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi may not be used if some other element in the clause is in focus, as illustrated in (49), where the presence of a focused adverb is incompatible with the occurrence of a floating quantifier (in any linear order):

Floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi consequently show a range of properties indicating an association with focus.Footnote 5 This suggests that the licensing of focus should also enter into the analysis of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi.

3.5 The proposal: FQ stranding in a low FocusP projected above vP

Putting all of the observations in 3.1–3.4 together, we propose that floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi arise as the result of DP movement first to a low focus projection, followed by NP-sub-extraction and raising to higher case positions, stranding the DP-remnant in SpecFocP.Footnote 6 The steps of this proposed derivation are described in (50) and illustrated in the structure (51) for a subject-related floating quantifier (note that in (51) for ease of visual representation, we do not show raising of the object to its surface position in the functional structure above FocP. Because it does not bear critically on the account developed here, we do not attempt any analysis of the internal structure of DPs and how nouns/NPs, numerals and classifiers are merged together within nominal phrases.Footnote 7

The two-step derivation proposed above is able to capture the full range of distinctive properties found with floating quantifier in Lalo Yi. First, the common emphatic-focused property of such elements is licensed via association with and movement to the specifier of a focus phrase (Property 4). Second, the observation that floating quantifiers occur in a fixed, low position in the clause is given an explanation and modeling—the licensing FocusP is projected in a single, fixed position immediately above vP, where numeral quantifiers are stranded (Property 2). The existence of low Focus phrases has been argued for in a broad range of languages on the basis of rich empirical patterns, including those languages noted in (52), and is language-internally supported in Lalo Yi by the observation that other focused-phrases are placed in the same, immediately pre-verbal position (3.4).

Third, the analysis provides a potential account of the observation that only one floating quantifier may occur per clause (Property 1)—there is (assumed to be) a single SpecFocP where focus is licensed, allowing for only one numeral-classifier pair to be focused. Such a focus analysis of the unique occurrence of floating quantifiers is further supported by other focus-related patterns in Lalo Yi. It is found that Lalo Yi elsewhere permits only one focus per clause. This is illustrated in (53) and (54) where speaker B attempts to correct speaker A’s initial assertion with two new pieces of focused information, and this is not possible in a single sentence:

The restriction on floating quantifiers to a singleton follows this general pattern if floating quantifiers are focused elements and only one focused constituent may be licensed per clause in SpecFocP. If floating quantifiers were instead assumed to arise via simple stranding of numeral-classifier pairs in the base merge position of subjects and objects, one might expect multiple floating quantifiers to occur, contra observation.

The analysis of floating quantifier patterns proposed here also makes available a way to capture the aspectual restrictions on subject-related floating quantifiers noted as Property 3. This extension of the analysis requires the introduction of additional background information on aspectual patterns observed in other languages and their effects on morpho-syntactic paradigms—the phenomenon of ‘aspect splits’ (Coon 2013; Kalin and van Urk 2015) described in 3.6.

3.6 Capturing aspectual restrictions on quantifier float

As noted above in 3.3, when clauses contain overt markers of perfective, experiential, or continuous aspect, it is possible for objects, but not subjects, to be construed with clause-final floating quantifiers. A structural approach to the occurrence of floating quantifiers that takes such elements to be stranded by movement to a low FocusP can be naturally developed to account for this patterning, drawing on the analyses of ‘aspect splits’ in other languages.

Aspect splits are instances in which contrastive morpho-syntactic patterns have been found to occur in clauses with different aspect-marking. In Coon (2013), and Kalin and van Urk (2015), it is shown that case-marking and verbal agreement may vary according to the type of aspect that is present in a clause. Examples of such variation are noted in (55):

Broadly-speaking, the analysis given to this aspect-dependent variation in Coon (2013) is that, in certain aspects, the subject is merged in a higher syntactic position, as the specifier of the aspectual verb/morpheme, and this higher position results in different patterns of subject-related case-marking and agreement that are different from those in clauses where the subject originates lower down in SpecvP. For reasons of space, we will not describe the details of how such a structural difference is potentially able to affect case and agreement relations (see Coon 2013:193–197). We will, however, adopt the fundamental insight offered by Coon (2013) that it is the syntactic height (initial merge position) of subjects in certain aspectual forms that is critically responsible for morpho-syntactic differences in aspect splits. In the case of Lalo Yi and the blocked construal of floating quantifiers in perfective, experiential, and continuous aspect forms, we propose, following the approach in Coon (2013), that the subjects in these aspectual clauses are merged in higher positions than in other aspects, in the specifier of an AspP that is external to vP and above the low FocusP, as shown in (56).

Such a difference in the base position of subjects will automatically offer an account of the subject-object asymmetry in floating quantifier construal. Whereas objects will be able to raise out of the VP and strand numeral-classifiers in SpecFocP before raising higher, subjects base-generated in SpecAspP will not be able to move through the lower FocusP, hence quantifier float and the construal of floating quantifiers with subjects will not be possible in these aspectual forms.

In sum, then, the general, structural analysis proposed in 3.5 and developed further, above, is able to model the set of features that characterize floating quantifier constructions in Lalo Yi relating to distribution, association-with-focus, and aspectual restrictions (Properties 1–4). A significant component of the proposed derivation is that numeral-classifier pairs are regularly stranded as the result of additional movement (of the NP) to a higher position.Footnote 8 In this patterning, Lalo Yi floating quantifiers bear a resemblance to certain movement constructions in other languages which give rise to the regularized stranding of some constituent, for example the obligatory stranding of particles with V2 patterns in German, and preposition-stranding in English wh-questions:

With these cases of particle and preposition stranding, there is no obvious syntactic or interpretational explanation for why stranding must occur, and it is simply accepted as an automatic part of the derivation.Footnote 9 Considering the hypothesized stranding of numeral quantifiers in Lalo Yi, one might ask whether this should also be viewed as a purely automatic reflex of the derivation (like particle/preposition-stranding), or whether there is an understandable motivation for its regularized occurrence. Here we will suggest that a plausible cause of the stranding pattern in Lalo Yi can indeed be identified, which relates this to assumptions concerning constraints on the licensing of information-structure in Rizzi (2006) and Shlonsky and Rizzi (2018)—‘criterial positions’ and ‘criterial freezing’ effects.Please note that the footnotes 12 and 15 have been moved to the end of the sentences “With these cases of particle and preposition...” and “Downing (1996) describes the use of...”. Kindly check and confirm.sure, no problem

The important intuition which we believe needs to be captured in cases of quantifier float in Lalo Yi is that numerically-quantified nominals [NP Num CL] need to be realized in two different locations: (a) a higher, case position, and (b) the lower, FocusP. Stranding, we suggest, is the solution that enables satisfaction of these two requirements—(partial) overt realization of the nominal in both case and focus positions. Raising of the noun/NP to the regular, vP external positions of subjects and objects will satisfy common case requirements relating to these positions and subjects/objects (and also constitute the end-point of the movement chain). Stranding of [Num CL] in FocusP can be attributed to a different requirement relating to movement which takes place to wh-, focus, and topic positions—‘criterial positions’ and ‘criterial freezing’ as described in Shlonsky and Rizzi (2018:29) and formalized in (59):

“In essence, when a phrase enters into a “criterial configuration”, a configuration dedicated to the expression of a scope-discourse-property (e.g., the final landing site of wh-movement, a left peripheral topic or focus position), the phrase is frozen, and becomes unavailable to further movement operations.” (Shlonsky and Rizzi 2018:29)

Taking the low FocusP in Lalo Yi to be a criterial position, DPs raised to SpecFocP will automatically be frozen in this position and unable to undergo further movement. However, freezing in SpecFocP will not necessarily require that the entire DP be overtly realized in SpecFocP. As discussed in Rizzi (2006:114, 2007) and Hartmann et al (2018:6), sub-extraction remains possible from criterially-frozen constituents, allowing for subparts of a frozen constituent to undergo further movement to higher positions.Footnote 10 Consequently, following movement of a numerically-quantified DP to SpecFocP, the NP constituent contained within the DP is able to undergo raising to a higher case position, stranding the DP remnant in FocP, and causing this to be pronounced as [DP Num CL]. In such a way, different parts of the DP will be overtly realized in two locations, the NP satisfying regular case-related requirements, and the DP-remnant conforming to Criterial Freezing, pronounced in SpecFocP.Footnote 11 The regularized nature of floating quantifier stranding in Lalo Yi can thus be attributed to the interaction of higher case-licensing probes with movement to a low focus projection and the effects of Criterial Freezing. What now needs to be clarified, and potentially explained, is how quantifier float in Lalo Yi may (or may not) be different from patterns found in other numeral-classifier languages, and how to account for differences that occur. In Sect. 4, we will compare Lalo Yi with Japanese to illustrate connections and dissimilarities in their use of both non-floated and floating quantifiers, and then make a proposal to account for the distinctive Lalo Yi patterns, from a cross-linguistic perspective, in Sect. 5.

4 Quantifier float in Lalo Yi and Japanese: a comparison

In Sects. 1 and 2, it was observed that the use of numeral-classifiers in nominal modification/quantification structures in Lalo Yi appears to be significantly different from related forms in other numeral-classifier languages. Section 2 also showed that a critical factor underlying Lalo Yi-internal distinctions in the use of numeral-classifier constituents as modifiers is specificity—in instances of referentially-asserted non-specific reference, numeral-classifier pairs always occur in the floating quantifier patterns discussed and analyzed in Sect. 3, and this is the patterning which makes Lalo Yi look quite different from other languages. Elsewhere, when numerically-quantified nominals have either specific indefinite or non-referential non-specific interpretations, numeral-classifier pairs appear adjacent to nouns/NPs in Lalo Yi, in a way that seems cross-linguistically very common. The question we would now like to consider is whether the distinctive patterns in Lalo Yi really are fundamentally different in nature from other numeral-classifier languages, or whether (non-)specificity might perhaps play a role in distinguishing numerically-quantified nominal forms more broadly in other languages.

While many properties of floating quantifiers have been intensively studied in numeral-classifier languages over the years—in particular issues relating to locality restrictions on construal, telicity, and distributivity—little attention has been given to the potential effects of specificity on speakers’ use of floated versus non-floated quantifiers and apparent optionality in the ways that numeral-classifier pairs are syntactically combined with the nouns/NPs that they modify. Three works that have investigated such questions in the past are Downing (1996) and Minagawa (2008) for Japanese, and Kim (2005) on Korean. As the former two studies are more extensive and informative, we will first reference their conclusions/observations (on Japanese) and then explore data that directly compares quantifier float options in Japanese and Lalo Yi to see where differences and similarities may lie, and how to interpret such variation.

Downing (1996) describes the use of numeral-classifier constructions in a corpus study of Japanese, contrasting the ways that two very frequent linearizations of nouns, numerals, and classifiers schematized in (60) are used in different ways by speakers.Footnote 12

The generalizations that Downing draws from her corpus is that Pattern AFootnote 13 is regularly used for specific indefinites, while Pattern B occurs predominantly with non-specific indefinites, and less frequently with specific indefinites. This correlation between (non-)specificity and the form of numerically-quantified nominals is further supported with the use of constructed examples such as (61) and (62), where Pattern B is naturally used for non-specific indefinite reference, and Pattern A for specific indefinites:

Minagawa (2008) concurs with Downing’s characterizations of the relation of (non-)specificity to Patterns A and B. She also emphasizes Downing’s observation that Pattern A tends to be used to re-introduce referents into a discourse, whereas Pattern B typically occurs in the initial introduction of referents, and ‘may be used only in cases where the information about number which it carries is new’ (Downing 1996:244), and ‘for this reason, it is largely confined to introductions. It also appears to be favored when the emphasis is on the number of referents involved’ (Downing 1996:262).Footnote 14

From the above, it can be seen that there are certain clear similarities between Japanese and Lalo Yi relating to (non-)specificity, new information, and the patterns used to encode numerically-quantified nominals. Both Lalo Yi and Japanese make heavy use of a particular pattern for specific indefinites—only [NP nikhe Num CL] in Lalo Yi, and frequently [Num CL no NP] in Japanese. Additionally, both languages use a different form for non-specific indefinites, either exclusively (quantifier float in Lalo Yi), or with substantial frequency (Pattern B in Japanese), both these latter patterns occurring regularly in the first mention of unfamiliar referents in a discourse (existential assertion) and where there is emphasis on the numeral component as new information.

It is also relevant to note that Japanese Pattern B is a linearization that actually may correspond to two different structural forms, one in which Num+Cl are nominal-internal, and a second structure in which Num+Cl are nominal-external and occur as floating quantifiers, as represented in (63):Footnote 15

This now raises an interesting question. As Japanese Pattern B is frequently associated with non-specific indefinites in presentational contexts (with emphasis on number as new information), and as Pattern B may also correspond to a floating quantifier structure, might it be the case that Japanese is actually closer to Lalo Yi than an initial, casual inspection would suggest? Is it possible that Japanese may make use of similar derivational forms to Lalo Yi for numerically-quantified specific and non-specific indefinites, with floating quantifier patterns being used for the former, and nominal-internal Num-CL for the latter, as in Lalo Yi? In order to check for this possibility and whether the typologically ‘unusual’ patterning present in Lalo Yi might potentially be more widespread, we tested a set of data designed to probe the (non-)specific interpretation of floating quantifiers.Footnote 16 The results of this investigation are summarized below.

As previously reported, floating quantifiers in Japanese are indeed very natural with non-specific interpretations of a nominal (64):Footnote 17

However, floating quantifiers in Japanese were also judged to be acceptable in cases where there is specific indefinite reference, as illustrated in (65), unlike in Lalo Yi:Footnote 18

It was further confirmed that floating quantifiers in Japanese may appear in positions other than those that are immediately pre-verbal, as shown in (66), unlike in Lalo Yi, where such elements are restricted to occurring in a fixed position immediately before the verb. Additionally, the occurrence of a floating quantifier in a higher position potentially allows for either a non-specific or a specific construal of the associated nominal. Consequently, (66) can be followed with either of the continuations in (67):

A comparison of such patterns with the descriptions of corpus and intuition-based generalizations in Downing (1996), Minagawa (2008), and other works leads to the following conclusions. First, as already noted, there are various observable similarities between Japanese and Lalo Yi in their frequent use of different numeral-classifier patterns for non-specific and specific reference, including the occurrence of floating quantifiers.Footnote 19 However, such common patterns of use would appear to be preferences and tendencies in Japanese, whereas they have reached a different status in Lalo Yi and become fully regularized with no remaining optionality. Comparing Japanese and Lalo Yi, in Japanese floating quantifiers may in principle occur with either non-specific or specific nominal reference, while in Lalo Yi such patterns are the automatic (and exclusive) signature pattern of non-specific nominals. In Japanese, there is no necessity for floating quantifiers to occur in immediate pre-verbal position, and floating quantifiers may occur in higher positions (associated with either specific or non-specific interpretations), but in Lalo Yi floating quantifiers must always be verb-adjacent and cannot be distributed across other positions. Two other syntactic patterns further confirm structural differences between Japanese and Lalo Yi in the occurrence of numeral classifiers. In Japanese, sequences of [N-case Num CL] can be coordinated as shown in (68), but this is not possible in Lalo Yi with equivalent, referentially-asserted non-specific nominals, as seen in (69) and noted in Li and Bu (2021):

Second, sequences of [N Num CL] may occur as fragment answers in Japanese, but parallel [N Num CL] sequences are unacceptable as fragments in Lalo Yi, as shown in (70) and (71):

Both patterns indicate that [N Num CL] sequences may be single nominal constituents in Japanese but not in Lalo Yi (which requires a floating quantifier structure in such instances).Footnote 20

Consequently, it has to be concluded that the syntax proposed to underlie the derivation of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi must not be a (necessary) feature of Japanese, and Lalo Yi remains typologically distinctive in its numeral-classifier patterns, despite the connections that can be highlighted to related patterns in languages such as Japanese. In Sect. 5, we discuss what broad conclusions can be drawn from Lalo Yi and its distinctive forms and how these patterns should be analyzed in relation to other numeral-classifier languages with purely optional quantifier float.

5 Lalo Yi: the development of a marked Num-CL system

We began this paper with the observation that Lalo Yi exhibits a highly unusual distribution of its numeral quantifiers which appears to be the opposite of patterns found in other numeral-classifier languages, where numerals and classifiers combine with nouns/NPs to create constituents that can be syntactically manipulated by other processes, for example, movement, case-marking, ellipsis. Such commonly-occurring patterns frequently do not seem to be possible in Lalo Yi, and are instead replaced with obligatory floating quantifier structures, giving rise to a typologically very marked use of numeral classifiers, which may even be unique among languages currently described. In this, the Lalo Yi patterns present a natural challenge to the assumption that floating quantifiers are special forms derived from more basic, neutral nominal structures in which numeral quantifiers are merged directly with nouns. Floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi might seem to be the basic structure created by the grammar, and so potentially support the ‘adverbial’ analysis of such forms, in which floating quantifiers have no derivational connection with non-floated nominals with numeral quantifiers, being merged as independent constituents in their surface positions.

Over the course of the paper, however, we have argued for an analysis in which floating quantifiers are in fact the result of a single nominal constituent undergoing separation during the course of the syntactic derivation, stranding numeral-classifier pairs when NPs move to higher positions, in a way that is broadly similar to preposition-stranding in p-stranding languages such as English. Such an approach was prompted by a consideration of additional patterns that occur with indefinite, numerically-quantified nominals and the novel observation that Lalo Yi differentiates such elements according to properties of specificity and referentiality, as represented in (72) (repeated from (31)):

Significantly, the striking, obligatory floating quantifier patterns characterize non-specific, referentially-asserted indefinites, and the other indefinite types in (72) indicate that nouns/NPs are commonly merged with numerals and classifiers, suggesting that such syntactic combinations should also be possible with non-specific, referentially-asserted indefinites. In order to account for the surface forms of the latter, we developed an analysis in which Num-CL and NP are initially merged together and subsequently separated in order to realize two syntactic positions with overt lexical material: (a) a low focus position associated with the emphasis of new information, and (b) a higher case position. The analysis was then shown to be able to capture a range of properties associated with floating quantifier constructions in Lalo Yi, relating to the fixed position of floating quantifiers, focus, and interactions with aspect.

In proposing such a modeling, we take the position that there is no need to postulate an additional adverbial source of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi, and that a potential adverbial approach is furthermore unsuited to Lalo Yi, being unable to account for aspects of the distribution of floating quantifiers that are more straightforward consequences of the stranding analysis. A primary reason for rejecting an adverbial modeling is one of over-generation. While it might be possible to suggest that numeral-classifier pairs could be directly merged in adverb-like ways, to allow for their occurrence in examples such as (10) and (11), there seems to be no plausible way for such an approach to also fully block numerals and classifiers from merging with nouns/NPs as single nominal constituents in contexts of non-specific, referentially-asserted indefinites. In all other numeral-classifier languages, if there is independent support for an adverb analysis of floating quantifiers in certain instances, such a syntactic option is found to exist alongside the possibility for Num + CL to also merge with NP and form a single syntactic constituent, which can appear in a range of different positions. However, such a patterning is not possible in Lalo Yi with non-specific referentially-asserted nominals, and there appears to be no way to block this over-generation from occurring, without brute-force stipulation that isn’t supported by other evidence or explanatory power. As emphasized in 2.1, to the best of our knowledge there are no other cases, cross-linguistically, where two elements, X + Y, are naturally combined in many instances while, in others, they can be blocked from being merged unless an additional element, Z, is later merged in the same constituent. Such a syntactic constraint would be quite exceptional, but would have to be posited to block the occurrence of [NP Num CL] in non-specific uses while permitting NP to merge with Num+CL when a D-type element is added (a demonstrative or nikhe) as [NP D Num CL]. The same constraint would also need to block the combination of nouns, numerals, and classifiers [NP Num CL] in non-specific referentially-asserted indefinites, while permitting the same combinations in instances of non-specific indefinites that are not referentially-asserted. We believe that the basic operation of merge should not be subject to such fine, contextual restrictions in its operation and hence that any exclusively adverbial approach to floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi will be negatively affected by an inability to capture non-floated numerals and classifiers in a principled/convincing way.Footnote 21

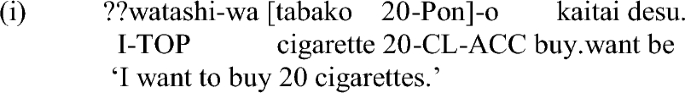

Two further empirical considerations that argue against an adverbial approach to floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi concern the general patterning of adverbs in the language and restrictions on the construal of floating quantifiers with nominals that are not subjects or direct objects. First, whereas adverbs/adverbial elements in Lalo Yi may occur in a range of different positions in a clause, show syntactic mobility, and are iterable, floating quantifiers are restricted to a single position, immediately preceding the verb (3.2), and may not be iterated (3.1). Floating quantifiers consequently do not have the common distributional properties of adverbs in Lalo Yi. Second, it can be noted that floating quantifiers may not be interpreted as modifiers of nominals that occur as indirect objects or in PPs, as illustrated in (73/74):

As PPs and indirect objects elsewhere disallow extraction in Lalo Yi (data not shown here), such patterns are simple for a sub-extraction stranding analysis to accommodate, but have no obvious explanation in an adverbial modeling. In English, where an adverb analysis of floating both and all has been motivated and defended (Bobaljik 2003; Fitzpatrick 2006), it is found that such elements can be construed with indirect objects (raised to SpecTP):

We therefore find a range of reasons to seriously doubt the appropriateness of a potential adverbial analysis of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi, and suggest that a stranding approach is indeed better placed to capture the properties of such elements, as has been proposed in the paper.Footnote 22

A final, important question for the analysis which has been developed here is how it can capture the typologically unusual numeral quantifier paradigm in Lalo Yi in a way that is both supported by language-internal evidence and allows for cross-linguistic variation and the occurrence of different floating quantifier patterns in languages such as Japanese (and Korean, Thai, Bangla etc.). What is responsible for such variation and how do the observed differences in numeral-classifier forms emerge across languages? The answer we would like to offer to this broad theoretical question attributes the relevant variation to the language-particular grammaticalization of focus, as follows. At the core of our analysis of Lalo Yi has been the suggestion that in presentational, non-specific interpretations, numeral-classifier pairs are elements that are regularly focused information in Lalo Yi, causing movement to a low focus projection associated with the emphasis of new information in a clause. As Lalo Yi does not permit multiple foci in a single clause (Sect. 3.5, ex. (53) and (54)), it is found that floating numeral classifiers may not co-occur in clauses with other focused elements such as focused adverbials (Sect. 3.4, ex. (49)). Such co-occurrence restrictions are significantly not found in other numeral-classifier languages such as Japanese, where floating quantifiers may occur in clauses that contain other focused elements, as shown in (76–78) (focused elements marked in bold).

We take this to signify a critical difference between Lalo Yi and Japanese. Whereas numeral quantifiers may quite generally be natural candidates for emphasis as new information in the presentation of non-specific indefinites, as indeed noted by Downing (1996) and Minagawa (2008), in Japanese such elements may also potentially occur without special emphasis and simply provide additional, modifying information as floating quantifiers in contexts where some other element is interpreted as being in focus, as in (76–78). We suggest that what has occurred in Lalo Yi, by way of contrast, is the full regularization of a common, interpretive tendency to construe numeral quantifiers as focal information in the presentation of new referents, so that numeral-classifier pairs with referentially-asserted non-specific indefinites can now only be associated with focus syntax as new information foci. The distinctive patterns found in Lalo Yi, from such a perspective, would be due to the grammaticalization of focus (movement) with numeral quantifiers, in combination with case requirements of subject and object DPs forcing further movement (and stranding) to occur. The striking variation found when Lalo Yi is compared with other numeral-classifier languages can consequently be fully accommodated and made sense of as the innovation of a new focal category, in a process that repeatedly produces differences across languages, with focus-driven movement showing clear variation in different languages—both in terms of the location of clausal focus projections and with regard to the classes of items that undergo automatic/optional focus movement (see, for example, differences among Romance languages in the fronting of new information focus as discussed in Cruschina 2021—regularly present in Sicilian and Sardinian, but not found in French, Italian or Spanish, except in sporadic cases of mirative focus). Rather than being a disconnected, perplexing oddity, the rich paradigm of numeral quantification in Lalo Yi can be seen as the natural outcome of a system that has expanded via mechanisms that are broadly available and attested, incorporating particular aspects of information structure and interpretation directly into syntactic structure and derivations.

Notes

The DP-internal ordering of NP, numeral, and classifier may show certain linear variation in different languages, which is not relevant for the discussion at hand (though see Jenks 2013a). (3a) is a sequencing that is found in Japanese, Korean, Burmese, Thai and many other numeral-classifier languages.

The term ‘specificity’ has been used in different ways in the literature. We follow the approach in von Heusinger (2002, 2011) and von Heusinger and Bamyacı (2017) which recognizes three common subtypes of specificity: referential specificity, scopal specificity, and epistemic specificity. All three subtypes of specificity are marked in the same way in Lalo Yi. For extensive discussion and a broad range of context-embedded examples of specificity in Lalo Yi, see Hu and Simpson (forthcoming).

For further examples and discussion of the mutually-exclusive use of the three patterns in (31a–c) for the different interpretations noted, see Hu and Simpson (forthcoming).

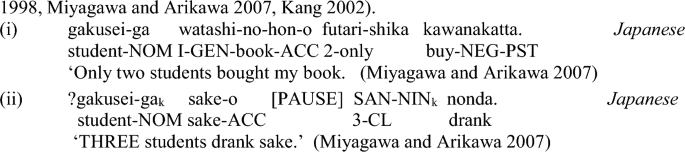

Similar, strong associations of floating quantifier patterns with focus have been noted in Burmese and Thai in Simpson (2011), and Jenks (2013a, b), and in Japanese and Korean it has been noted that floating quantifiers are often associated with focus-type prosody and/or morpho-syntactic focus-markers, such as (equivalents to) ‘as many as’, ‘only’, ‘even’—in particular when floating quantifiers associated with subjects occur to the right of objects (Takami 1998, Miyagawa and Arikawa 2007, Kang 2002).

There are various possibilities, including the modelings given to similar linear sequences of [NP Num Cl] in Japanese, Korean, Thai, and Burmese in Watanabe (2006), An (2018), Simpson (2008), and Jenks (2011), or for the [NP Dem Num Cl] patterns found in another Yi language, Nuosu Yi, in Jiang (2018). Probing the internal structure of Lalo Yi DPs would require considerably extra space here and so will be kept as a project for a future study.

A reviewer of the paper asks what might rule out an alternative, non-stranding analysis of floating quantifier patterns, in which the NP would be base-generated in a high position c-commanding the raised DP, with the latter containing both a numeral-classifier pair and a pro coindexed with the higher, associated NP, as schematized in (i):

(i) …NPm….[DP [NP prom ] Numeral Classifier]k…tk..

Such structures would fail to capture the patterns noted here and in 3.3 relating to aspectual restrictions on floating quantifiers, which are unavailable when the subject is base-generated in a higher aspect-related position. If the analysis of the aspectual patterns proposed in the current section is correct, it indicates that a simple c-command relation between the NP and the numeral-classifier pair is not sufficient to license coreference, and movement/stranding must be involved in floating quantifier constructions, with NP and Num-CL being base-generated together and subsequently undergoing separation. Additionally, the potential availability of non-stranding structures such as (i) would seem to suffer from the over-generation problem described in Sect. 5—it would lead one to expect that the [NP pro ] could be overtly lexicalized and that referentially-asserted indefinites would be able to surface as single constituents [DP NP Num CL], rather than as discontinuous structures, contra observation.

Grammaticality/acceptability judgments here are for regular colloquial English.

An alternative perspective on the stranding-separation patterns that might be adopted is to assume the occurrence of distributed deletion (Fanselow and Ćavar 2002), and partial, complementary deletion applying to numerically-quantified DPs in two positions. It could be assumed that [DP NP Num CL] first raises to FocP and then higher to a case position. At PF, distributed deletion might then apply causing the higher copy to be pronounced as just the NP component, and the lower copy as simply the Num-CL pair:

We will not pursue such an alternative further here, as it would not seem to conform with the Criterial Freezing approach we have adopted, in which the DP raised to SpecFocP is immobilized in this position.

The element no is a linker (or genitive case marker) in Japanese, with no inherent semantic content.

Downing refers to Pattern A as the ‘NP-internal pattern’, and Pattern B as ‘NP-external’ (occurrence of Num CL).

Downing mentions a similar observation relating to Papago in Lee (1983:259), recording that Lee ‘...found that floated quantifiers [in Papago] typically appear in introductory mentions of characters and are used only when the information carried by the quantifier is new.’

This structural ambiguity occurs when case-markers immediately follow the NP, which are the occurrences that are of interest here. When case-markers alternatively follow the classifier ([NP Num Cl]-case), numeral-classifier pairs are unambiguously contained within the nominal and hence are not floating quantifiers. Downing describes the use of [NP Num CL]-case patterns as being less frequent, and occurring in contexts of ‘apposition’, where they repeat information about number already known to the hearer, adding that the number information in such patterns is of low prominence (not in focus).

Thanks to Tomoko Ishizuka and Satoshi Shigeoka for their help with judgments of the data.

Fully nominal-internal occurrence of the numeral-classifier was judged to be unnatural/odd in such cases:

Reference to ‘friends of the speaker’ forces a specific reading, due to the familiarity inherent between a speaker and his/her friends. By way of contrast, reference to the purchase of cigarettes in (64) naturally causes a non-specific reading.

While Kim (2005) does not consider floating quantifiers separated from nouns/NPs by other material, she does note that Korean speakers use different nominal forms in (non-)specific reference with numeral quantifiers, observing that [NP-case Num CL] sequences are only used for non-specific reference, while [NP Num CL]-case patterns may occur with either specific or non-specific reference.

The only way that (71A) can be answered is with a full sentence, allowing for a floating quantifier to occur:

Approaching one part of the Lalo Yi Num-Cl paradigm from a semantic perspective, Li and Bu (2021) suggest that the use of numeral-classifier pairs as predicates in nominal phrases is simply blocked, but they do not offer any explanation for why this might be so. Such constituents clearly do occur regularly as predicates in clauses—see examples (18) and (34)—hence it is unclear why this should not be possible in nominal phrases. Additionally, as shown in the current paper, numeral-classifier pairs do occur in both non-referential non-specific nominals and specific indefinite nominals (which Li and Bu do not mention in their paper), casting doubt on the speculation that such elements are unable to occur as predicates within nominal constituents. Finally, Li and Bu’s assumption that ‘Num-Cl behave(s) differently between indefinite and definite phrases’ (Li and Bu 2021:2) is descriptively not accurate, as Num-Cl crucially may indeed occur in indefinite nominals of the two types just mentioned. It can be noted that Liu and Bu (2018) also present certain generalizations which now appear to be incorrect or incomplete, for example: ‘we can draw a conclusion that Lalo Yi is a language that does not have the nominal quantifier; namely, the language does not have the sequence of N+Num+Cl’ (Liu and Bu 2018:7) and ‘nominal arguments without modifying elements in Lalo Yi can only have two syntactic forms: [NP N] or [DP N+Dem+Num+Cl]’ (Liu and Bu 2018:9). This characterization ignores the significant occurrence of [N+Num+Cl] with non-referential indefinite nominals and [N+nikhe+Num+Cl] with specific indefinites, which must be taken into consideration in any modeling of numeral-classifier syntax in Lalo Yi. While Liu and Bu (2018) and Li and Bu (2021) are both valuable contributions, the former for its focus on different relative clause types in Lalo Yi, and the latter for its comparison of native and borrowed numerals, an analysis of floating quantifiers in Lalo Yi must take into account the full range of patterns that are found in the language.

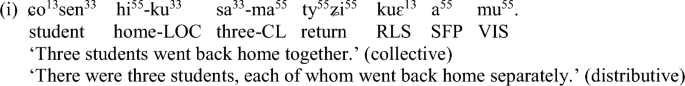

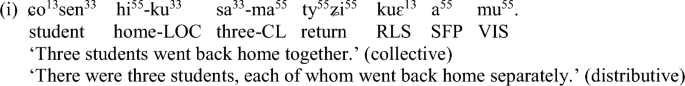

In Ishii (1999), it is also argued that floating quantifiers that are merged independently from NPs in an adverbial way necessarily give rise to distributive readings, whereas numeral quantifiers that are directly merged with NPs do not have such a restriction and allow for either distributive or collective interpretations. In this regard, it can be noted that Lalo Yi floating quantifiers permit both distributive and collective interpretations, and hence pattern in the way of numeral quantifiers directly merged with NPs, as illustrated in (i):

References

Aboh, Enoch O. 2007a. “Focused vs. non-focused wh-phrases.” In Focus strategies in African languages, ed. Enoch O. Aboh, Katharina Hartmann, and Malte Zimmermann, 287–314. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Aboh, Enoch O. 2007b. “Leftward focus vs. rightward focus: The Kwa-Bantu conspiracy.” SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics 15: 81–104.

Aikhenvald, Alexandra. 2003. Classifiers: A typology of noun categorization devices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

An, Duk-ho. 2018. On the word order of numeral quantifier constructions. Studia Linguistica 72 (3): 662–686.

Belletti, Adriana. 2001. Inversion as focalization. In Subject inversion in Romance and the theory of Universal Grammar, ed. Aafke Hulk and Jean-Yves. Pollock, 69–90. New York: Oxford University Press.

Belletti, Adriana. 2004. Aspects of the low IP area. In The structure of CP and IP, ed. Luigi Rizzi, 16–51. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bisang, Walter. 1999. Classifiers in East and Southeast Asian languages: Counting and beyond. In Numeral types and changes worldwide, ed. J. Gvozdanovic, 113–185. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bobaljik, Jonathan. 2003. Floating quantifiers: handle with care. In The Second Glot International State-of-the-Article Book: The latest in linguistics, ed. Lisa Cheng and Rint Sybesma, 107–148. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Coon, Jessica. 2013. TAM split ergativity. Language and Linguistics Compass 7 (3): 171–200.

Cruschina, Sylvia. 2021. The greater the contrast, the greater the potential: On the effects of focus in syntax. Glossa 6 (1): 3. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.1100.

Downing, Pamela. 1996. Numeral classifier systems: The case of Japanese. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Dowty, David, and Belinda Brodie. 1984. The semantics of “floated” quantifiers in a transformationless grammar. In Proceedings of the 3rd west coast conference on formal linguistics, ed. S. Mackaye and M.T. Wescoat, 75–90.

Erguvanı, Eser. 1984. The function of word order in Turkish grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Evans, Jonathan. 2022. Classifiers before numerals. Asian Languages and Linguistics 3 (2): 1–21.

Fanselow, Gisbert, and Damir Ćavar. 2002. Distributed deletion. In Theoretical approaches to universals, ed. Artemis Alexiadou, 65–107. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Fitzpatrick, Justin. 2006. The syntactic and semantic roots of floating quantification. Doctoral Dissertation, Cambridge: MIT.

Fukushima, Kazuhiko. 1991. Generalized floating quantifiers. Doctoral Dissertation. Tucson: University of Arizona.

Harris, Alice. 1981. Georgian syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hartmann, Jutta, Marion Jäger, Andreas Kehl, Andreas Konietzko, and Suzanne Winkler. 2018. Exploring the concept of freezing: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. In Freezing: Theoretical approaches and empirical domains, ed. Jutta Hartmann, Marion Jäger, Andreas Kehl, Andreas Konietzko, and Suzanne Winkler, 1–25. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hu, Yaqing, and Andrew Simpson. Forthcoming. Specificity contrasts in Lalo Yi: Structure and interpretation. Accepted to appear in Studies in Language.

Ishii, Yasuo. 1999. A note on floating quantifiers in Japanese. In Linguistics: in search of the human mind, a Festschrift for Kazuko Inoue, ed. Masatake Muraki and Enoch Iwamoto, 236–237. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

Jayaseelan, K.A. 2001. IP-internal topic and focus phrases. Studia Linguistica 55 (1): 39–75.

Jenks, Peter. 2011. The hidden structure of Thai noun phrases. Doctoral Dissertation, UC Berkeley.

Jenks, Peter. 2013a. Accounting for a generalization about quantifier float and word order in classifier languages. Berkeley: University of California.

Jenks, Peter. 2013b. Quantifier float, focus, and scope in Thai. Proceedings of Berkeley Linguistics Society (BLS) 39: 90–107.

Jiang, Li Julie. 2018. Definiteness in Nuosu Yi and the theory of argument formation. Linguistics and Philosophy 41: 1–39.

Kalin, Laura, and Coppe van Urk. 2015. Aspect splits without ergativity. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 33: 659–702.

Kang, Beom-Mo. 2002. Categories and meanings of Korean floating quantifiers: With some reference to Japanese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 11 (4): 375–398.

Kim, Alan. 1988. Preverbal focusing and type XXIII languages. In Studies in syntactic typology, ed. M. Hammond, E. Moravcsik, and J.R. Wirth, 147–169. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Kim, Christina. 2005. Order and meaning: numeral classifiers and specificity in Korean. In Proceedings of the 24th west coast conference on formal linguistics, ed. John Alderete, Chung-hye Han, and Alexei Kochetov. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Kiss, Katalin. 1998. Identificational focus versus informational focus. Language 74 (2): 245–273.

Ko, Heejeong. 2007. Asymmetries in scrambling and cyclic linearization. Linguistic Inquiry 38: 49–83.

Ko, Heejeong. 2014. Edges in syntax: Scrambling and cyclic linearization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kuno, Susumo. 1978. Danwa no bunpo [The grammar of discourse]. Tokyo: Taishukan.

Lee, Hyo Sang. 1983. Word order and quantifier floating in Papago and Pima. Ms. UCLA.

Li, Xuping, and Weimei Bu. 2021. Semantics for numerals in Lalo Yi. In Paper presented at the TripleA 8 conference. University of Singapore.

Liu, Hongyong, and Weimei Bu. 2018. The syntax of relative clauses in Lalo Yi. In Proceedings of the 51st international conference on Sino-Tibetan languages and linguistics. http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235294.

Mahajan, Anoop. 1990. The A/A-bar distinction and movement theory. Doctoral Dissertation. Cambridge: MIT.

Mahajan, Anoop. 1992. The specificity condition and the ECP. Linguistic Inquiry 23 (3): 510–516.

Manetta, Emily. 2010. Wh-expletives in Hindi-Urdu: The vP Phase. Linguistic Inquiry 41 (1): 1–34.

McCloskey, James. 2000. Quantifier float and wh-movement in an Irish English. Linguistic Inquiry 31: 57–84.

Minagawa, Harumi. 2008. Quantifier position in Japanese and the domain of specificity and indefiniteness. Journal of Japanese Linguistics, 69–87.

Miyagawa, Shigeru. 1989. Structure and case-marking in Japanese. San Diego: Academic Press.

Miyagawa, Shigeru. 2017. Numeral quantifiers. In Handbook of Japanese syntax, ed. Masayoshi Shibatani, Shigeru Miyagawa, and Hisashi Noda, 581–609. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Miyagawa, Shigeru, and Koji Arikawa. 2007. Locality in syntax and floating numeral quantifiers. Linguistic Inquiry 38 (4): 645–670.

Nakanishi, Kimiko. 2008. The syntax and semantics of floating numeral quantifiers. In The Oxford handbook of Japanese linguistics, ed. Shigeru Miyagawa and Mamoru Saito, 287–319. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ndayiragije, Juvenal. 1999. Checking economy. Linguistic Inquiry 30 (3): 399–444.

Neeleman, Ad., and Elena Titov. 2009. Focus, contrast, and stress in Russian. Linguistic Inquiry 40 (3): 514–524.

Paul, Waltraud. 2005. Low IP area and left periphery in Mandarin Chinese. Recherches linguistiques de Vincennes 33. http://journals.openedition.org/rlv/1303.

Post, Mark. 2022. Classifiers in a language with articles. Asian Languages and Linguistics 3 (2): 239–267.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2006. On the form of chains: Criterial positions and ECP effects. In Wh-movement: Moving on, ed. Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng, and Norbert Corver, 97–134. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2007. On some properties of Criterial Freezing. In CISCL working papers on language and cognition, Vol. 1, pp. 145–158.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2015. Notes on labelling and subject positions. In Structures, strategies, and beyond, ed. Elisa Di Domenico, Cornelia Hamann, and Simona Matteini, 17–46. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Shlonsky, Ur, and Luigi Rizzi. 2018. Criterial freezing in small clauses and the cartography of copular constructions. In Freezing: theoretical approaches and empirical Domains, ed. Jutta Hartmann, Marion Jäger, Andreas Kehl, Andreas Konietzko, and Susanne Winkler, 29–65. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Simpson, Andrew. 2008. Classifiers and DP structure in Southeast Asia. In The Oxford handbook of comparative syntax, ed. Guglielmo Cinque and Richard Kayne, 806–838. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simpson, Andrew. 2011. Floating quantifiers in Burmese and Thai. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 4 (1): 115–146.

Sportiche, Dominique. 1988. A theory of floating quantifiers and its corollaries for constituent structure. Linguistic Inquiry 19 (3): 425–449.

Takami, Ken-Ichi. 1998. Nihongo-no-suuryoosi yuuri-ni-tuite [On quantifier float in Japanese). Gengo [Language) 1:3:86–95, 98–107.

von Heusinger, Klaus. 2002. Specificity and definiteness in sentence and discourse structure. Journal of Semantics 19: 245–274.

von Heusinger, Klaus. 2011. Specificity. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, Vol. 2, ed. Klaus von Heusinger, Claudia Maienborn, and Paul Portner, 1025–1058. Berlin: de Gruyter.

von Heusinger, Klaus and Elif Bamyacı. 2017. Specificity effects of Turkish differential object marking. In Proceedings of the 12th workshop on altaic formal linguistics (WAFL12), ed. Leyla Zidani-Eroğlu, Matthew Ciscel, and Elena Koulidobrova, 145–156. Cambridge: MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

Watanabe, Akira. 2006. Functional projections of nominals in Japanese: Syntax of classifiers. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 24: 241–306.

Zhang, Niina. 2000. Object shift in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Chinese Linguistics 28 (2): 201–246.

Acknowledgements

We thank Weimei Bu and her family and friends for sharing the data presented in this paper. We would also like to thank the audiences of the 45th DGfS 2023 AG2 Divide and Count: On the (Morpho-)Syntax and Semantics of Division, Plurality and Countability and TEAL-13 for their feedback.

Funding

Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Simpson, A. Floating quantifiers, specificity and focus in Lalo Yi. J East Asian Linguist (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-023-09272-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-023-09272-8