Abstract

Unlike typical wh-questions, why-questions are known to be focus-sensitive, but the linguistic realization of their focus sensitivity shows an unexpected pattern in Japanese. The phrase that immediately follows a causal wh-phrase can be considered as the focus associate without any focal prominence. This prosodic pattern contradicts the generally accepted view that a focused phrase invariably receives focal prominence (pitch boost) in Japanese. The paper presents an analysis based on focus movement for this surprising prosodic pattern. We characterize the focus sensitivity of a why-question as an association-with-focus effect with the silent focus exhaustivity operator. The adjacency of a causal wh-phrase and the focus associate is a result of the focus movement to the operator position, which mimics the focus movement proposed by some of the advocates of focus association by movement (Krifka in The Architecture of Focus 82:105, 2006; Wagner in Natural Language Semantics 14(4):297-324, 2006; as reported by Erlewine (Movement out of focus, 2014)). We argue that the adjacency strategy, which places a focus associate immediately after why, is a syntactic manifestation of association with focus, and that this structural disambiguation makes prosodic marking unnecessary. The proposal brings a functional perspective to the syntax–semantics–prosody correspondence in such a way that a focus-marked phrase does not automatically lead to prosodic prominence and the phonological interpretation of focus is influenced by the consideration of usefulness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

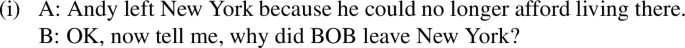

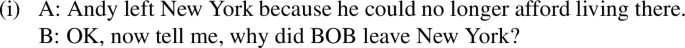

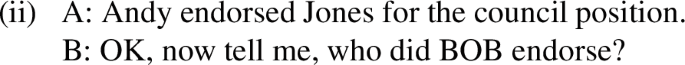

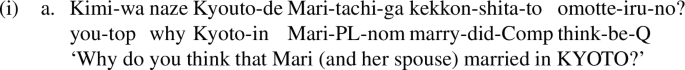

There is another kind of focalization effect, which is exemplified in (i).

Examples like (i) should be kept apart from the effects in (1). A case like (i) is more accurately described as an instance of contrastive topic, which can be analyzed as a wide-scope focus which out-scopes a question (cf. Constant 2014; Wagner 2012; Tomioka 2010a; b), which results in the meaning paraphrasable asFootnote 1 continued ‘as for BOB, why did he leave New York?’ Unlike (1), this type of focalization strategy is not limited to why-questions.

It is also worth noting that in the Japanese translations of these questions, the focalized phrases are marked with the topic marker wa, as noted in Tomioka (2010a). On the other hand, focus associates of why-questions in Japanese are never wa–marked, which indicates that the phenomenon exemplified in (1) is not a contrastive topic.

In all the Japanese examples in the paper, the focus associates are lexically accented words, and their focus prominence, when it is present, is indicated by the capitalization of the words.

Kawamura (2007) argues that the adjacency relation between why and its focus associate in the cleft construction is a consequence of constituency between the two phrases. Kawamura’s argument will be closely examined in Sect. 4, and for the time being we will stay descriptive and continue to refer to it as the adjacency effect.

(17) may be felicitous under the interpretation that the speaker is interested in knowing why John bought beer but not in why Andy did. However, such an interpretation is a contrastive-topic reading of the focus prominence, as briefly discussed in footnote 1.

The repeated/reinforced question after an elliptical question is not limited to why. For instance, the following conversation is natural and easily imaginable: ‘I saw Wes Anderson’s new movie.’ ‘When? When did you see it?’ Such a sequence is also possible in Japanese.

All the native speakers I consulted choose to place prominence on the same focused phrase as in the antecedent, but some wonder whether the second occurrence receives slightly reduced prominence compared to the first occurrence. The same issue may arise in Japanese. One reviewer reports that under some circumstances, prosodic marking becomes unnecessary even with focus-at-distance cases like (4), and I admit that there may be some speakers who can maximize the contextual cues to obtain the intended effects without assigning strong prominence to the focused phrases.

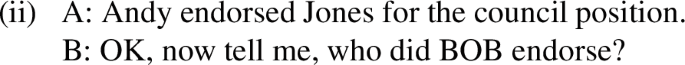

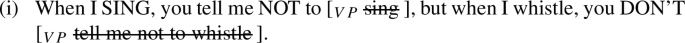

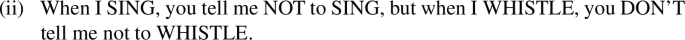

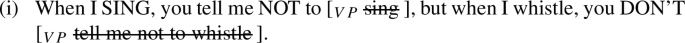

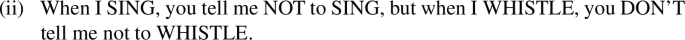

The pattern observed in (23) is reminiscent of a case of ‘sloppy’ ellipsis discussed in Schwarz (2000, Chapter 4). The elided VP in the second conjunct in (i) contains another smaller elided VP which yields the sloppy interpretation.

Schwarz (2000) observes that when the elided VPs are pronounced, the smaller VPs ([\(_{VP}\) sing ] and [\(_{VP}\) whistle ] ) receive prosodic prominence that is indicative of the presence of focus.

Presently we are not certain whether and how the two phenomena are related.

With the hypothesis that the focus sensitivity of why is due to \({exh}_{F}\), a new question arises: why is it not possible to have \({exh}_{F}\) in other constituent questions? We will address this question in the Appendix to this paper.

Since I will later adopt a movement theory of focus association, the semantic type of the exhaustive operator will be different from the sentential operator version of it. See Section 3.1 below.

Kawamura (2007) proposes a different analysis of the exhaustivity based on the event-semantic partition inspired by Herburger (2000). Her account treats why itself as a focus sensitive expression, but the discussion of fragmental why-questions earlier in this section has revealed that such an analysis is inconsistent with the generalization concerning focus-containing ellipsis. Kawamura’s solution also requires some mechanical tools which are not independently motivated. On the other hand, an account based on exhaustivity associated with focus is consistent with the generalization of focus-containing ellipsis and requires no ad hoc machinery.

There are a couple of issues that arise with the proposal. First, what happens if a causal wh-phrase undergoes movement? Does \({exh_{F}}\) move along with it? The assumption here is that the two elements are always local to each other both at Spell Out and LF. Thus, if why moves, \({exh_{F}}\) should also dislocate to stay close to why. However, it is not clear at this point whether various possible positions of why are created by movement or are the consequences of the relative freedom of the locations where why can be generated. See Rizzi (2001) and Ko (2005) for relevant discussion. The second issue is whether a why question always comes with \({exh_{F}}\). The complement of why need not contain a focused constituent. With the sentence, ‘Why is the train late?’, the speaker is asking for the reason of the train’s delay, and this interpretation shows no focus sensitivities. Thus, either \({exh_{F}}\) is optional in a why-question or \({exh_{F}}\) is always present but chooses the negation of the prejacent of why as the default alternative when the prejacent has no focus. The obligatory presence of \({exh_{F}}\) becomes a trickier issue, however, if it is not a sentential operator, as discussed in the next subsection. I will leave the optionality of \({exh_{F}}\) as an open question.

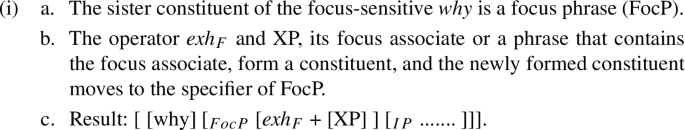

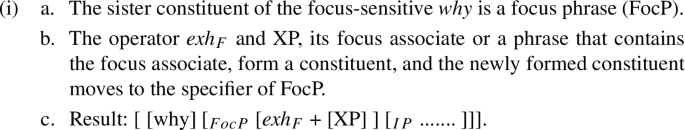

There remains a question of how the proximity of why and the focus exhaustivity operator \({exh_{F}}\) is accounted for. One possible way to capture the locality effect is summarized in (i).

One reviewer wonders whether why and \({exh_{F}}\) can ever be separated; in particular, whether it is possible to generate a structure in which why is located at the matrix level but \({exh_{F}}\) is confined within an embedded clause. This is an intriguing question that we nonetheless are unprepared to address properly.

We ignore the difference in the surface positions of the topic-marked Anna.

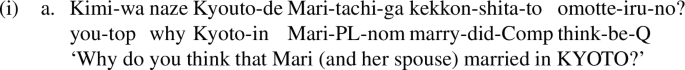

An anonymous reviewer asked whether the movement to \({exh_{F}}\) is not just island-sensitive but more restricted in a way that is reminiscent of QR – whether it is clause-bound. The following example, similar to the one presented by the reviewer, suggests that a long distance movement is possible.

The ambiguity is structural: naze Kyouto-de can be either inside or outside of the embedded clause. The sentence is indeed ambiguous (although the matrix reading is easier to obtain if the matrix verb is changed to omou-no ‘think-Q’ without the progressive marker). This indicates that a focused phrase can move out of an embedded clause to \({exh_{F}}\) in the matrix clause. It is consistent with the fact that the cleft formation can be long-distance. The reviewer further asks whether this ambiguity has impact on the prosody, in particular whether placing focus prominence on Kyouto-de can elicit one scope reading over the other. The current proposal makes no prediction in this regard, and the empirical facts are unclear, as we have obtained no firm judgments so far. I will leave this issue as an open question.

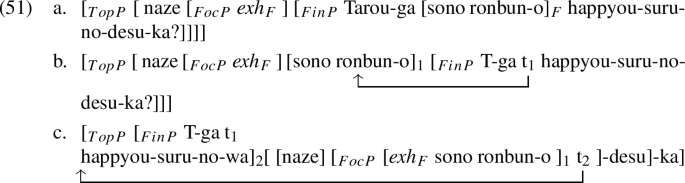

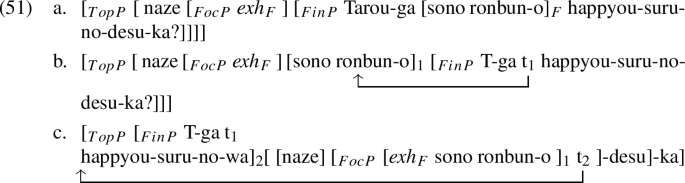

Incidentally, it is noteworthy that (47) does not require any prosodic marking on the focused phrase sono ronbun: it is indeed much more natural not to assign any prosodic prominence to it. It is consistent with the previous conclusion that prosodic marking is done only when there is a potential ambiguity in the location of focus.

To this example, the polite copula desu and the Q-marker ka are added. It is customary in the Japanese syntax literature that the sentence final no is regarded as the Q-marker. It should be pointed out, however, that this particle is homophonous with the finiteness marker. It is possible that its use as the Q-marker is derived from the structure no-desu-ka where the copula and the true Q-marker are unexpressed. The addition of desu-ka is to avoid the issue of the true identity of no.

Unlike the exhaustivity of a ‘free’ focus, the exhaustive meaning in the cleft construction is not conversational, as it is extremely hard to cancel it. While there seems to be a consensus that it is a conventional meaning, its exact nature is still being debated. See Büring and Kriz (2013) for an account that treats it as a presupposition.

An anonymous reviewer suggests that naze and the focus phrase may form a ‘surprising constituent’ in the sense of Takano (2002). While we admit that this possibility cannot be easily dismissed, the examination in the section shows that a constituency is not necessary to account for the pattern observed by Kawamura. Moreover, an analysis based on constituency would require that naze itself be a focus sensitive operator that uses the focus semantic value of the focused phrase, but, according to the data examined in Section 2, such an analysis is hard to justify.

Exactly how to account for the case marker drop is still being debated. In Hiraiwa and Ishihara (2012), the case-less version is considered an entirely different construction, which they call pseudo-cleft. This construction is a bi-clausal structure in which the presupposed clause is embedded under a nominal projection (DP) headed by no. This DP and the focused phrase in the pivot are in a predicational relation, and the material in the pivot is the focus that is exhaustively interpreted. The derivation of the case-less version of (45) is shown below.

I am grateful to Chris Tancredi, who pointed out this problem to me.

References

Baumann, Stefan. 2016. Second occurrence focus. In The oxford handbook of information structure, ed. Caroline Féry and Shinichiro Ishihara, 483–502. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Beaver, David I., Brady Clark, Edward Stanton Flemming, T. Florian Jaeger, and Maria Wolters. 2007. When semantics meets phonetics: Acoustical studies of second-occurrence focus. Language 83 (2): 245–276.

Beck, Sigrid. 2006. Intervention effects follow from focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 14: 1–56.

Bocci, Giuliano, Luigi Rizzi, and Mamoru Saito. 2018. On the incompatibility of Wh and focus. GENGO KENKYU (Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan) 154: 29–51.

Bromberger, Sylvain. 1992. On what we know we don’t know: Explanation, theory, linguistics, and how questions shape them. USA: University of Chicago Press.

Büring, Daniel. 2015. A theory of second occurrence focus. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 30 (1–2): 73–87.

Büring, Daniel, and Manuel Kriz. 2013. It’s that, and that’s it! Exhaustivity and homogeneity presuppositions in clefts (and definites). Semantics and Pragmatics 6: 1–29.

Chierchia, Gennaro, Danny Fox, and Benjamin Spector. 2012. The grammatical view of scalar implicatures and the relationship between semantics and pragmatics. In Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning, de Gruyter, ed. Klaus von Heusinger, Claudia Maienborn, and Paul Portner. Manuscript: Harvard University & MIT.

Constant, Noah. 2014. Contrastive topic: Meanings and realizations. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Drubig, Hans Bernhard. 1994. Island constraints and the syntactic nature of focus and association with focus. Universitäten Stuttgart und Tübingen in Kooperation mit der IBM Deutschland GmbH.

Erlewine, Michael Yoshitaka. 2014. Movement out of focus. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Erlewine, Michael Yoshitaka, and Hadas Kotek. 2018. Focus association by movement: Evidence from tanglewood. Linguistic Inquiry 49 (3): 441–463.

Féry, Caroline, and Shinichiro Ishihara. 2010. How focus and givenness shape prosody. In Information structure: Theoretical, typological, and experimental perspectives, ed. Malte Zimmermann and Caroline Féry, 36–63. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fox, Danny. 2007. Free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. In Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics, ed. Uli Sauerland and Penka Stateva, 71–120. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Han, Chung-hye, and Maribel Romero. 2004. Disjunction, focus, and scope. Linguistic Inquiry 35 (2): 179–217.

Herburger, Elena. 2000. What counts: Focus and quantification. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Hiraiwa, Ken, and Shinichiro Ishihara. 2012. Syntactic metamorphosis: Cleft, sluicing, and in-situ focus in Japanese. Syntax 15: 142–180.

Ishihara, Shinichiro. 2011. Japanese focus prosody revisited: Freeing focus from prosodic phrasing. Lingua 121: 1870–1889.

Jacobs, Joachim. 1991. Focus ambiguities. Journal of Semantics 8 (1–2): 1–36.

Kawamura, Tomoko. 2007. Some interactions of focus and focus sensitive elements. Ph.D. thesis, Stony Brook University, SUNY.

Ko, Heejeong. 2005. Syntax of why-in-situ: Merge into [Spec, CP] in the overt syntax. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 23: 867–916.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1991. The representation of focus. In Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research, ed. Arnim von Stechow and Dieter Wunderlich, 825–834. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, Angelika, and Junko Shimoyama (2002), Indeterminate pronouns: The view from japanese. In Proceedings of the third tokyo conference on psycholinguistics, ed Yukio Otsu. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Krifka, Manfred. 1994. The semantics and pragmatics of weak and strong polarity items in assertions. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory 4: 195–219.

Krifka, Manfred. 2001. For a structured meaning account of questions and answers. Audiatur vox Sapientia. A Festschrift for Arnim von Stechow 52: 287–319.

Krifka, Manfred. 2001. Quantifying into question acts. Natural Language Semantics 9 (1): 1–40.

Krifka, Manfred. 2006. Association with focus phrases. The Architecture of Focus 82: 105.

Nagahara, Hiroyuki. 1994. Phonological Phrasing in Japanese. Ph.D. thesis, UCLA.

Nirit, Kadmon. 2001. Formal pragmatics. USA: Blackwell Publishers.

Pierrehumbert, Janet, and Mary Beckman. 1988. Japanese tone structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Poser, William. 1984. The phonetics and phonology of tone and intonation in Japanese. Ph.D. thesis, MI.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2001. On the position of “Int(errogative)’’ in the left periphery of the clause. In Current studies in Italian syntax, ed. G. Cinque and G. Salvi, 267–296. Siena: Ms. Università di Siena.

Rooth, Mats. 1985. Association with focus. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 117–121.

Schwarz, Bernhard. 2000. Topics in ellipsis. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts – Amherst.

Selkirk, Elizabeth O. 2006. Bengali intonation revisited: An optimality theoretic analysis in which FOCUS Stress prominence drives FOCUS phrasing. In Topic and focus: Cross-linguistic perspectives on meaning and intonation, ed Matthew Gordon Lee, Chungmin and Daniel Büring. 215–244. Dordrecht: Springer.

Shinya, Takahito. 1999. Eigo to nihongo ni okeru fookasu ni yoru daunsteppu no sosi to tyooon-undoo no tyoogoo [The blocking of Downstep by Focus and Articulatory Overlap in English and Japanese]. Proceedings of Sophia Linguistics Society 14: 35–51.

Takano, Yuji. 2002. Surprising constituents. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 11 (3): 243–301.

Tancredi, Christopher. 1990. Syntactic association with focus. In Proceedings from the first meeting of the Formal Linguistic Society of Mid-America, 289–303.

Tancredi, Christopher. 1992. Deletion, deaccenting, and presupposition. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Tancredi, Christopher. 2004. Associative operators. GENGO KENKYU (Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan) 125: 31–82.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2007. Intervention effects in focus: From a Japanese point of view. In ISIS Working Papers of the SFB 632, ed Shinichiro Ishihara, Potsdam University, vol. 9.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2009. Why questions, presuppositions, and intervention effects. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 18: 253–271.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2010a. Contrastive topics operate on speech acts. In Information structure from different perspectives, ed M. Zimmermann and F. Caroline, OUP. 753–773.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2010. A scope theory of contrastive topics. Iberia 2: 113–130.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2017. Focus–prosody mismatch in japanese why-questions. In Proceedings of WAFL 13, ed Tomoyuki Yoshida, Céleste Guillemot and Seunghun J. Lee, MITWPL, 269–279.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2020. Exhaustivity of focus and anti-exhaustivity of contrastive topic. Theoretical Linguistics 46 (1–2): 123–132.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 1995. Phonological Phrases: Their relation to syntax, focus, and prominence. Ph.D. thesis, MIT.

Von Stechow, Arnim. 1982. Structured propositions. Arbeitspapiere des SFB 99 59, Universität Konstanz Konstanz, Germany.

Wagner, Michael. 2006. Association by movement: Evidence from NPI-licensing. Natural Language Semantics 14 (4): 297–324.

Wagner, Michael. 2012. Contrastive topics decomposed. Semantics & Pragmatics 5 (8): 1–54.

Wold, Dag E.. 1996. long distance selective binding: the case of focus. In Proceedings of SALT VI, ed Teresa Galloway and Justin Spence, Ithaca. 311–328. NY: CLC Publications.

Yoshida, Masaya, Chizuru Nakao, and Ivan Ortega-Santos. 2015. The syntax of why-stripping. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 33 (1): 323–370.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank, first and foremost, the three anonymous reviewers who read the manuscript carefully and gave me a number of valuable comments and suggestions. This paper is a much revised and expanded version of Tomioka (2017). It was originally presented at the satellite workshop, Prosody, Syntax and Information Structure in Altaic, at the 13th Workshop in Altaic Formal Linguistics (WAFL 13), held at International Christian University in 2017. I would like to thank Yoshi Kitagawa, the co-organizer of the satellite workshop, for giving me a chance to begin this project. I had very useful and insightful discussions at the workshop with Yoshi Kitagawa and several other participants, most notably Chris Tancredi and Junko Ito. Special thanks to Amanda Payne for helping me prepare the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Exhaustivity in Wh-questions

The lack of exhaustive implicatures in constituent questions is discussed in Tomioka (2020).

Appendix: Exhaustivity in Wh-questions

One of the key factors in the proposed analysis in the paper is that a focused phrase in a why-question is associated with the exhaustivity operator (\({exh_{F}}\)), rather than why itself. The fact that other constituent questions are not focus sensitive means that they cannot host \(\textit{exh}_{F}\), and one naturally wonders why that is so. This appendix addresses this issue, but we can offer only a preliminary analysis.

In many information-structure-based analyses of wh-questions (e.g., Krifka 2001a), wh-phrases themselves are regarded as foci, and the question of whether there are additional (non-wh) foci in constituent questions is a non-trivial matter. On the one hand, it has been observed that a (non-why) wh-phrase and a focus cannot co-occur in some languages. Italian is a well-known case (cf. Rizzi 1997; 2001). In connection with intervention effects in wh-questions, Tomioka (2007) claims that a (non-wh) focus in a wh-question is illegitimate in Japanese, regardless of their surface positions, and Bocci et al. 2018 offer an analysis that unites Italian and Japanese in this regard. On the other hand, English wh-questions can seem to host additional focused items, as in (2), repeated as (56).

While some have argued for the possibility of a non-wh focus in a constituent question (e.g., von Stechow 1982; Kadmon 2001), the focused phrases in (56) are realized as contrastive topics in the translations into languages in which contrastive topics are easily distinguished from foci (with Japanese being one such language). Whether non-wh foci in constituent questions are unambiguously contrastive topics or not, one fact is clear: focused phrases in constituent questions cannot be interpreted exhaustively. For instance, the question, who did ANNA meet on Friday? with focal prominence on ANNA, cannot mean ‘which person x is such that it is Anna that met x on Friday?’. If this interpretation were available, the following conversation would be well-formed.

C’s utterance was meant to correct the exhaustivity associated with ANNA, but its infelicity indicates that exhaustivity is absent in A’s question.

This in turn means that the following structure is not permitted:

We propose the following descriptive constraint to block (58):

(48) can differentiate why-questions from other wh-questions. It has been suggested (e.g., Rizzi 2001; Ko 2005) that why is merged directly into the specifier of CP without leaving any trace within the TP. For instance, the two sentences in (1) have the following LF representation, in which \({exh_{F}}\) is attached to the TP that contains no wh-traces.

As for the source of the constraint in (48), we speculate that it is based on interpretability. Suppose that all wh-phrases have Hamblin-style denotations and are moreover interpreted in situ (via LF reconstruction or the deletion of the higher copy in the Copy-and-Delete theory of movement). There are at least two compositional mechanisms to implement the Hamblin semantics.

Whichever mechanism is chosen, the exhaustivity operator \({exh_{F}}\) cannot perform its duty: it is a sentential operator whose prejacent is a proposition. Its contribution to the meaning is to exclude non-weaker alternatives to its prejacent. If we adopt (61a), then, a wh-containing TP denotes a set of propositions, rather than a proposition. Thus, the exhaustification is undefined. The other choice also fails to work for \({exh_{F}}\). If \({exh_{F}}\) is attached to a constituent containing a wh-phrase but not the relevant Q-morpheme, the ordinary semantic value of that constituent is undefined. Since \({exh_{F}}\) negates all the non-weaker alternatives to the ordinary semantic value, the operation cannot be performed if the ordinary semantic value is undefined.

While the proposal explains the lack of focus-related exhaustivity in non-why constituent questions, it crucially relies on the assumption that all wh-phrases reconstruct and are interpreted in their original positions. It remains to be seen if this assumption is independently justified.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tomioka, S. Focus without pitch boost: focus sensitivity in Japanese why-questions and its theoretical implications. J East Asian Linguist 31, 73–98 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-022-09235-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-022-09235-5