Abstract

Many children do not realize the physical health, mental health, cognitive, and academic benefits of physical activity because they are insufficiently active. Effectively promoting physical activity in children requires understanding the determinants of physical activity. Parent physical activity and support for physical activity have emerged as central influences, but few studies have applied longitudinal designs and device-based measures of child physical activity. The purposes of this cohort study were to examine direct associations between parent physical activity and child physical activity, parent physical activity and parent support for physical activity, and parent support and child physical activity; and to examine indirect associations between parent physical activity and child physical activity, mediated through parent support behaviors. We used structural equation modeling with panel analysis to examine direct and indirect influences of parent physical activity and support on 7th grade children’s physical activity, adjusted for 5th grade levels. Parent surveys were administered at the 5th grade time-point. Parent physical activity indirectly affected child physical activity, mediated through the parent support behavior of providing transportation for physical activity. Parent physical activity was also directly related to four parent support behaviors. Increasing parent support for child physical activity, and possibly parent physical activity, may be effective approaches to increasing child physical activity.

Highlights

-

Parent physical activity is indirectly related to child physical activity.

-

Parent physical activity influences child physical activity through parent support.

-

Increasing parent instrumental support likely increases child physical activity.

-

Increasing parent physical activity may increase child physical activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Children accrue substantial physical health, mental health, cognitive, and academic benefits when they participate in regular physical activity (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). Accordingly, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018) and the World Health Organization (DiPietro et al., 2020) recommend that children engage in 60 or more minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity daily. However, less than 25% of 6-to-17-year-olds in the U.S. (Merlo et al., 2020) and less than 20% of adolescents aged 11–17 years globally (Guthold et al., 2020) meet the 60 minute daily physical activity guideline. Furthermore, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity declines as children age (Farooq et al., 2020). Therefore, promoting physical activity in youth is a public health priority in the U.S. and around the world (DiPietro et al., 2020; Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee, 2018).

Designing effective program, policy, and environmental interventions to promote physical activity requires understanding influences on physical activity in children. The child’s social environment, especially parent physical activity behavior and parent support for physical activity, have emerged as central influences on child physical activity (Carter et al., 2022; Gerards et al., 2021; Hutchens & Lee, 2018; Orehek & Ferrer, 2019; Rhodes et al., 2020a; Rhodes & Quinlan, 2014). Multiple reviews have consistently found associations between parent support and child physical activity (Edwardson & Gorely, 2010; Gustafson & Rhodes, 2006; Yao & Rhodes, 2015), and these associations hold for assessments of influences on child physical activity around the globe (Harrington et al., 2016). Yao and Rhodes (2015) conducted a meta-analysis that examined the associations between specific support behaviors and child physical activity and found small, positive effect sizes (r = 0.14 to 0.28), with composite measures of multiple support items yielding medium effect sizes (r = 0.38). Parent support behaviors are distinct behaviors (Rhodes et al., 2015), and it remains unclear which specific aspects of parent support are most influential on child physical activity. Hence, we focused this report on some specific indicators of parent behaviors that have been suggested by prior studies to be influential on children’s physical activity (Yao & Rhodes, 2015).

Conceptually, parent influences on child physical activity include parenting practices (e.g., providing social support, such as encouragement and providing transportation), parent characteristics (e.g., parent movement behaviors including modeling of physical activity), family demographics, home environment, and parenting styles, which take place within a broader socioecological context (e.g., community, cultural, normative, policy, and media influences) (Rhodes et al., 2020a). This paper focuses on the parental behaviors of providing social support for child physical activity and parent participation in physical activity. Parent social support for physical activity consists of specific parental actions that shape their child’s physical activity (Gerards et al., 2021; Hutchens & Lee, 2018). These include instrumental support (e.g., providing funding, transport, and/or equipment) that enables participation in physical activity, parent involvement in child’s physical activity (e.g., being physically active with their child), monitoring child’s physical activity, and parental encouragement of physical activity (Carter et al., 2022; Gerards et al., 2021; Hutchens & Lee, 2018). Social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2004) suggests that parent physical activity, also known as role modeling, may influence child physical activity directly through observational learning (Carter et al., 2022). However, there is mixed evidence concerning the direct impact of parent physical activity behavior on child physical activity behavior. A recent review, based largely on cross-sectional studies, found weak but positive associations (r = 0.10 to 0.20) between parent physical activity behavior (modeling) and child physical activity (Petersen et al., 2020). But two reviews (Jaeschke et al., 2017; Rhodes et al., 2020b) and a longitudinal study (Gerards et al., 2021) found no direct associations between parent physical activity and child physical activity. These varying findings may result from differing methodologies (i.e., systematic review versus meta-analysis) and the small numbers of studies with varying age groups of children (e.g., preschool, children, and/or adolescents) included in the review articles.

The effects of parent physical activity on child physical activity may be indirect as well as direct (Carter et al., 2022). For example, in a cross-sectional study, Carter et al. (2022) reported that parent physical activity did not influence self-reported child physical activity directly; rather, it influenced parent provision of instrumental support, which was associated with child physical activity. Thus, parent physical activity was associated with child physical activity indirectly, through supportive parent behaviors. Parent physical activity and parent support likely co-occur to varying degrees to shape the family’s physical activity social environment. Most studies and reviews examined only direct associations among child physical activity, parent physical activity behavior, and parent support behaviors. This approach does not consider the complexity of the home social environment (Carter et al., 2022) or the need to examine mediating variables (Matos et al., 2021). Furthermore, most studies reviewed were cross-sectional in design and many used the child’s self-report of physical activity (Edwardson & Gorely, 2010; Gerards et al., 2021; Gustafson & Rhodes, 2006; Hutchens & Lee, 2018; Petersen et al., 2020; Wilk et al., 2018; Yao & Rhodes, 2015).

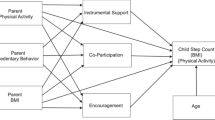

Accordingly, this study examined the influences of both parent physical activity and parent social support for child physical activity on child physical activity. Specifically, the purposes of the current longitudinal study with device-based assessment of child physical activity were to examine: 1) direct associations between parent physical activity and child physical activity; 2) direct associations between parent physical activity and parent support for physical activity, and between parent support and child physical activity; and 3) indirect associations between parent physical activity and child physical activity, mediated through supportive parenting behaviors. Figure 1 presents the conceptual model tested in this study.

Methods

Design

The data from this study come from the Transitions and Activity Changes in Kids (TRACK) study, an observational cohort study of physical activity and multiple domains of determinants of physical activity as students transitioned from elementary (2010) to middle school (2012) and high school (2017). Data for this study were collected from students drawn from 21 elementary schools, who subsequently enrolled in 12 middle schools within two school districts in South Carolina, in 2010–2012 and analyzed in 2022. One district, located in north-central South Carolina, had a population of 226,046 persons in 2010 (75% white, 19.4% black, and 11.2% living in poverty). The second district, located in central South Carolina, had a population of 107,490 persons in 2010 (48% white, 48% black, and 19.1% living in poverty) (United States Census Bureau, 2010).

Fifth grade children were invited to participate at recruitment assemblies held at the elementary schools. Informed consent packets were sent home with the children for parents to read, complete, and return. Students were excluded from the study only if they had an orthopedic or other condition that would invalidate the measure of physical activity (e.g., children who used a wheelchair), and/or intellectual limitations that would preclude proper completion of the survey. Additional details on study recruitment protocols and the original TRACK sample have been reported previously (Pate et al., 2019a, b).

Children reported their sex and self-identified as Hispanic or Latino and as American Indian or Alaskan Native, Black, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, Asian, or Other (e.g., multiracial). A parent/guardian completed a questionnaire about their sport participation, leisure time physical activity, support for their child’s physical activity, and educational attainment as a surrogate measure of family socio-economic status. Parents selected one of six optional education levels, ranging from “attends or has attended high school” to “completed graduate school.” For this study two categories were created, corresponding to high school graduation or less, and attendance at college/technical school or more. Child and parent survey items used in this study were completed when the child was in the 5th grade. Child physical activity was measured in the 5th (elementary school) and 7th (middle school) grades using accelerometry. Prior to data collection, parent/guardian consent and child assent were obtained. The Institutional Review Board at the University of South Carolina approved the protocols.

Participants

The original sample of 1080 5th grade children (46% boys, 54% girls) was limited to children with accelerometer data (989; 46% boys, 54% girls); those missing parent education (n = 58), parent physical activity (n = 55), parent encouragement (n = 44), and accelerometer data from the 7th grade (n = 250) were not included. There were no sex or parent education differences between those included and not included. Children were categorized as Black, Hispanic, White, and Other. There were fewer children in the Hispanic and Other race/ethnic groups in the analytic sample. Also, in initial modeling, the Hispanic race/ethnic group (n = 54) was dropped due to lack of fit, leaving 548 in the analytic sample. Of the 548 children, 47% were boys, 40% were Black, 42% White, and 58% had a parent with greater than a high school education. Eighty-seven percent of parent responders were mothers. Mean age of the children at 5th grade was 10.6 ± 0.5 years (Table 1).

Measures

Physical activity

Child physical activity was measured in the 5th and 7th grades using accelerometry (ActiGraph GT1M and GT3X models, Pensacola, FL). Each child wore an accelerometer on his/her right hip for seven consecutive days during waking hours, except while bathing, swimming, or sleeping. Data were collected and stored in 60-second epochs. Any period of 60 or more minutes of consecutive zeros was considered non-wear time and recoded to missing. Physical activity was calculated using an age-specific prediction equation (Freedson et al., 2005) generalized to the mean age of the TRACK cohort. The threshold for total physical activity was >100 counts per minute. Data for Sundays were excluded from the analysis due to the shorter amount of average wear time on that day. Missing data were imputed by sex for participants with at least 2 days of 8 or more hours of wear time. Multiple imputation regressions in Proc MI in SAS (Version 9.3; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) using all 7 days of physical activity variables (sedentary, light, and moderate-to-vigorous) were conducted. A total of five data sets were imputed and then averaged for each variable. Light and moderate-to-vigorous were summed to obtain total physical activity per day and divided by hours of monitor wear time to obtain total physical activity per hour for each of six days.

Parent physical activity and parent support

Parent items were completed when the child was in the 5th grade. Parents completed items about their sport (4 items) and leisure time physical activity (4 items) (Baecke et al., 1982) and reported their education attainment. Also, parents reported support for their child’s physical activity using four items (Sallis et al., 2002) that asked them how many days in a typical week they engage in four types of parent support that support physical activity. The items included “encourage your child to do physical activity or play outside,” “play outside or do physical activity with your child,” “provide transportation to a place where he or she can do physical activity,” and “watch your child participate in physical activities or outdoor games.” The items were rated from 1 to 5 with the following response categories: 0, 1-2, 3-4, 5-6 and 7 days.

Statistical Analyses

A structural equation model tested the hypothesized model presented in Fig. 1. A panel analysis (Kessler & Greenberg, 1981) examined if parent behavior and parent support when the child was in the 5th grade were related to child total physical activity in the 7th grade. The panel model simultaneously computes all relationships among variables at 7th grade after partialling out all cross-sectional relationships at 5th grade and all the autocorrelations of the variables between the 5th and 7th grades. A robust weighted least squares estimation with mean- and variance-adjusted test (WLSMV) was used due to binary covariates.

The model included four observed variables, “encourage your child to do physical activity or play outside,” “play outside or do physical activity with your child,” “provide transportation to a place where he or she can do physical activity,” and “watch your child participate in physical activities or outdoor games” and two latent variables: 1) parent physical activity (2 indicators) and 2) child objectively measured total physical activity (6 indicators). Physical activity was modeled as latent, rather than observed, variables to increase concurrent validity and reliability of the multiple measures (Dowda et al., 2021). Single indicators of parent behaviors were used to estimate specific aspects of parental support, which was the focus of the study. The structural model adjusted for measurement errors of the single indicators (Hoyle, 1995). The structural models included direct paths from parent physical activity to child physical activity and to the four parent support behaviors. There were also direct paths from the four supportive parent behaviors to child physical activity. Four indirect relationships via the four parent support behaviors were tested between parent physical activity and child’s physical activity. Models were adjusted for sex, parent education, and race/ethnicity. Standardized estimates results were reported.

Model fit was assessed according to multiple fit indices using decision rules described by Hoyle (Hoyle, 1995). A χ2 value that is non-significant is an indicator of optimal fit, but it is too sensitive to a large sample, so other indices are commonly used. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) represents closeness of fit. Values of ≤0.06 represent a close fit (Carmines & McIver, 1981), while 0 represents an exact fit (Bentler, 1990). The comparative fit index (CFI) tests the proportionate improvement in fit of the target model with the null model. CFI values approximating 0.90 indicate a minimally acceptable fit.

Results

As shown in Table 1, 5th grade total physical activity for children was 28.4 ± 4.5 min per hour of total physical activity. In the 7th grade their total physical activity was 22.8 ± 4.7 min per hour of total physical activity. The mean (SD) of items for parent physical activity and the four parent behaviors that support children’s physical activity are shown in Table 2. Parents reported more leisure-time physical activity (approximately 2 to 3 times per week, 2.5 ± 0.6) compared to sports participation (about 1 to 2 times per week, 2.0 ± 0.8). The most highly rated support item was “encourage your child to do physical activity or play outside,” (3.5 ± 1.1) and the lowest was “provide transportation to a place where he or she can do physical activity” (2.5 ± 1.1). Parent support behaviors averaged slightly below the midpoint of the range, indicating an approximate frequency of 2 to 3 times per week, except for “encourage your child to do physical activity or play outside,” which was slightly higher, at an approximate frequency of 4 to 5 times per week.

Figure 2 illustrates the panel model to assess the relationship among parent physical activity, the four parent support behavior items, and child’s 7th grade physical activity adjusted for 5th grade physical activity. Parent physical activity and parent support were reported at the 5th grade time point. All variables loaded significantly on the parent and child physical activity, and fit indices indicated that the model had adequate fit. Solid lines indicate significant p-values and dotted lines indicate non-significance of the relationship. The model provided acceptable fit (χ1572 = 323.1, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.044, (90% CI = 0.037, 0.051); CFI = 0.96).

Longitudinal panel model examining the impact of parent PA and parent support for child PA when the child was in the 5th grade were related to child total physical activity in the 7th grade Standardized correlations (β) between 5th grade parent physical activity, parent encouragement, do physical activity with child, provide transportation, watch child perform physical activity, and 7th grade child physical activity are shown, after adjustment for 5th grade relations and autocorrelations between 5th and 7th grades. Broken lines indicate nonsignificant correlations (p > 0.05). Model adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, and parent education. †p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, PA physical activity

There were significant relationships (p < 0.001) between parent physical activity and the four parent support items, β = 0.53, β = 0.78, β = 0.57, and β = 0.71, for “encourage your child to do physical activity or play outside,” “play outside or do physical activity with your child,” “provide transportation to a place where he or she can do physical activity,” and “watch your child participate in physical activities or outdoor games,” respectively. All other relationships were non-significant. There was a significant relationship between the parent support item “provide transportation to a place where he or she can do physical activity” (β = 0.18, p < 0.01) with child’s 7th grade total PA.

One of the four indirect relationships that were tested was found to be significant. The indirect relationship between parent physical activity and child’s physical activity at 7th grade, mediated by the supportive parent behavior of “provide transportation to a place where he or she can do physical activity,” was significant (β = 0.10, p = 0.02).

Discussion

The primary finding of the longitudinal panel analysis was that parent physical activity had an indirect effect on child physical activity that was mediated through the supportive parent behavior of “provide transportation to a place where he or she can do physical activity.” Few studies have examined direct and indirect mechanisms of influence among parent physical activity, parent support for physical activity, and child physical activity. Cross-sectional studies with child-reported physical activity used a similar analysis and also found that parent physical activity affected youth physical activity indirectly, mediated though parent instrumental support (Carter et al., 2022; Trost et al., 2003). This study extends the earlier work with a longitudinal examination of these relationships and device-based measures of children’s physical activity.

Studies on associations between parent physical activity and child physical activity have produced mixed findings, with most showing weak or no associations (Gerards et al., 2021; Jaeschke et al., 2017; Petersen et al., 2020) and one qualitative study indicating that parent physical activity can be a barrier to child physical activity (Rhodes et al., 2020a). Nonetheless, the results of this study suggest that parent physical activity behavior is an important influence on physical activity in their children, albeit indirectly through the provision of instrumental social support to the child (i.e., providing transportation to physical activity opportunities). This result underscores the importance of using longitudinal designs (Hutchens & Lee, 2018) and examining mediating variables as mechanisms of influence (Matos et al., 2021; Petersen et al., 2020) between parent physical activity and child physical activity. The findings of this study also show that it may be important to distinguish between parent behaviors, such as participating in sport or leisure physical activities, and parent support behaviors directed toward children, such as “play outside or do physical activity with your child” (co-participating in physical activity with child).

In addition to indirect effects in the longitudinal panel model, parent physical activity was significantly and directly related to the four supportive parent behaviors: “encourage your child to do physical activity or play outside,” “play outside or do physical activity with your child,” “provide transportation to a place where he or she can do physical activity,” and “watch your child participate in physical activities or outdoor games.” That is, parents who reported being more physically active also reported providing higher levels of all four supportive parent behaviors for their child’s physical activity. One of these four behaviors, “provide transportation to a place where he or she can do physical activity,” was also significantly and directly related to child physical activity. This variability in how individual supportive behaviors influence physical activity is consistent with the literature (Carter et al., 2022) and suggests that examining individual physical activity parent support behaviors may be more informative than using composite measures of social support for understanding parent influences on child physical activity.

Understanding the roles of direct and indirect influences of parent physical activity and parent support may more specifically inform child physical activity intervention targets and behaviors. This is important because systematic reviews and meta‐analyses show that physical activity interventions in children have had limited effects on increasing children’s objectively measured physical activity (Love et al., 2019; Metcalf et al., 2012). The results of this study, as well as others, suggest that intervention strategies for changing specific supportive parent behaviors, such as instrumental support for physical activity, may be effective (Doggui et al., 2021; Orehek & Ferrer, 2019; Rhodes et al., 2020a; Trost et al., 2003; Wilk et al., 2018). Another approach to promoting child physical activity is to examine how increasing parents’ physical activity may impact the physical activity behavior of their children (e.g., Rodrigues et al, 2018; Morgan et al., 2022; Rodrigues et al., 2018).

These findings indicate that parent physical activity is an important part of the child’s home social environment. Additional research is needed to fully define the elements of the home social environment (Rhodes et al., 2020a) and to examine how these may influence child physical activity directly and indirectly. In addition to parent physical activity behavior and parent support related to physical activity (Carter et al., 2022), variables not examined in this study, such as parent beliefs about physical activity, may be important (Rhodes et al., 2020a). For example, parent perceived behavioral control (Rhodes et al., 2015), additional psychosocial variables such as affective attitudes and intentions to support (Rhodes et al., 2020b), parent enjoyment of their own physical activity (Dowda et al., 2011; Trost et al., 2003), and parent beliefs about the importance (Dowda et al., 2011; Trost et al., 2003) and benefits of child physical activity (Rhodes et al., 2020a) may influence providing social support to the child. Parent perception of child’s athletic competence (Pfeiffer et al., 2009) also has been shown to influence child physical activity.

Child psychosocial characteristics not examined in this study may be influential elements of the home social environment for physical activity, as well. For example, the effects of parent physical activity may also be mediated through psychosocial variables such as child physical activity self-efficacy (Banik et al., 2021; Trost et al., 2003) and the effects of parent support may be mediated through child perceptions of parent support (Wilk et al., 2018). Parent influences could vary by other characteristics of the parent and child; for example, parent influences on physical activity varied by sex of the parent in combination with sex of the child (Carter et al., 2022; Cleland et al., 2011; Crawford et al., 2010; Forthofer et al., 2017; Jago et al., 2011). One recent study found that the association between parents and children meeting physical activity guidelines varied by the sex of the child (Dozier et al., 2020). The age of the child may also be important; for example, perceived social support from parents declined in boys and girls from grades 9 to 12 (Lau et al., 2016) and in girls from grades 8 to 12 (Dowda et al., 2007), and a recent review showed that children receive less support from parents as they age (Rhodes et al., 2020b).

Due to its complexity, this study focused on limited aspects of the child’s social environment, specifically, parent physical activity and parent behaviors that support child physical activity, and how these relate to child physical activity. In addition to more fully defining the home social environment related to physical activity, future work should consider multiple levels of influences and changes in these influences on children as they age. This could include an examination of direct, indirect, and moderating effects of the physical environment (Colabianchi et al., 2018; Dishman et al., 2017; Dowda et al., 2020; Gerards et al., 2021), child-level social cognitive variables (Dishman et al., 2017; Dowda et al., 2020; Wilk et al., 2018), and parent beliefs and attitudes (Rhodes et al., 2015).

Strengths of this study included the longitudinal design, multiple estimates of physical activity, a diverse cohort of children reflecting nearly equal numbers of boys and girls and equal numbers of Black and White children, and device-based assessment of child physical activity. A substantial strength was using an analytic approach that examined indirect (mediating) as well as direct effects of parent physical activity on child physical activity from elementary to middle school and that adjusted for cross-sectional relationships at 5th grade and autocorrelations of all variables between the 5th and 7th grades. Limitations include working with a cohort of children from two districts in one state in the U.S., which may limit generalizability; using only two data points; surveying only one parent (primarily mothers); and assessing parent physical activity via self-report. Another limitation was the need to exclude Hispanic youth from the sample due to lack of statistical modeling fit. Future studies should ensure inclusion of sufficient numbers of Hispanic youth to enable a statistical assessment of these relationships in this population.

Conclusion

A longitudinal panel analysis revealed that parent physical activity is indirectly related to child physical activity, with its effects mediated through the supportive parent behavior of “provide transportation to a place where he or she can do physical activity.” Working to increase specific parent support, such as providing instrumental support, and parent physical activity, may be effective approaches to increasing child physical activity. Future research is needed to more fully define and study how the home social environment directly and indirectly relates to physical activity in children, especially when considered within a framework that includes an examination of possible moderating effects of the physical environment, child, and parent social cognitive variables.

Data Availability

De-identified data from this study are not available in a public archive. De-identified data from this study will be made available (as allowable according to institutional IRB standards) by emailing the corresponding author.

Code Availability

Analytic code used to conduct the analyses presented in this study are not available in a public archive. They will be made available by emailing the corresponding author.

References

Baecke, J. A., Burema, J., & Frijters, J. E. (1982). A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 36(5), 936–942. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936.

Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31, 143–164.

Banik, A., Zarychta, K., Knoll, N., & Luszczynska, A. (2021). Cultivation and enabling effects of social support and self-efficacy in parent-child dyads. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 55(12), 1198–1210. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaab004.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Carmines, E. G., & McIver, J. P. (1981). Anayzing models unobserved variables. In G. W. Bohrnstedt & E. F. Birgatte(Eds.), Social measurement: Current issues. Sage.

Carter, J. S., DeCator, D. D., Patterson, C., McNair, G., & Schneider, K. (2022). Examining direct and indirect mechanisms of parental influences on youth physical activity and body mass index. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(4), 991–1006.

Cleland, V., Timperio, A., Salmon, J., Hume, C., Telford, A., & Crawford, D. (2011). A longitudinal study of the family physical activity environment and physical activity among youth. The American Journal of Health Promotion, 25(3), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.090303-QUAN-93.

Colabianchi, N., Clennin, M. N., Dowda, M., McIver, K. L., Dishman, R. K., & Porter, D. E., et al. (2018). Moderating effect of the neighborhood physical activity environment on the relation between psychosocial factors and physical activity in children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Epidemiology Community Health, 73(7), 598–604.

Crawford, D., Cleland, V., Timperio, A., Salmon, J., Andrianopoulos, N., & Roberts, R., et al. (2010). The longitudinal influence of home and neighbourhood environments on children’s body mass index and physical activity over 5 years: the CLAN study. International Journal of Obesity, 34(7), 1177–1187.

DiPietro, L., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S. J. H., Borodulin, K., Bull, F. C., Buman, M. P., et al. (2020). Advancing the global physical activity agenda: recommendations for future research by the 2020 WHO physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines development group. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01042-2.

Dishman, R. K., Dowda, M., McIver, K. L., Saunders, R. P., & Pate, R. R. (2017). Naturally-occurring changes in social-cognitive factors modify change in physical activity during early adolescence. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0172040. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172040.

Doggui, R., Gallant, F., & Belanger, M. (2021). Parental control and support for physical activity predict adolescents’ moderate to vigorous physical activity over five years. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 18(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01107-w.

Dowda, M., Dishman, R. K., Pfeiffer, K. A., & Pate, R. R. (2007). Family support for physical activity in girls from 8th to 12th grade in South Carolina. Preventive Medicine, 44(2), 153–159.

Dowda, M., Dishman, R. K., Saunders, R. P., & Pate, R. R. (2021). Associations between three measures of physical activity and selected influences on physical activity in youth transitioning from elementary to middle school. Sports Medicine and Health Science, 3(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smhs.2021.02.004.

Dowda, M., Pfeiffer, K. A., Brown, W. H., Mitchell, J. A., Byun, W., & Pate, R. R. (2011). Parental and environmental correlates of physical activity of children attending preschool. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(10), 939–944. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.84.

Dowda, M., Saunders, R. P., Colabianchi, N., Dishman, R. K., McIver, K. L., & Pate, R. R. (2020). Longitudinal associations between psychosocial, home, and neighborhood factors and children’s physical activity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 17(3), 306–312. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2019-0137.

Dozier, S. G. H., Schroeder, K., Lee, J., Fulkerson, J. A., & Kubik, M. Y. (2020). The association between parents and children meeting physical activity guidelines. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 52, 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2020.03.007.

Edwardson, C. L., & Gorely, T. (2010). Parental influences on different types and intensities of physical activity in youth: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(6), 522–535.

Farooq, A., Martin, A., Janssen, X., Wilson, M. G., Gibson, A.-M., & Hughes, A., et al. (2020). Longitudinal changes in moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews, 21(1), e12953 https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12953.

Forthofer, M., Dowda, M., O’Neill, J. R., Addy, C. L., McDonald, S., & Reid, L., et al. (2017). Effect of child gender and psychosocial factors on physical activity from fifth to sixth grade. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 14(12), 953–958. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2016-0487.

Freedson, P., Pober, D., & Janz, K. F. (2005). Calibration of accelerometer output for children. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 37(11), S523–S530.

Gerards, S., Van Kann, D. H. H., Kremers, S. P. J., Jansen, M. W. J., & Gubbels, J. S. (2021). Do parenting practices moderate the association between the physical neighbourhood environment and changes in children’s time spent at various physical activity levels? An exploratory longitudinal study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 168 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10224-x.

Gustafson, S. L., & Rhodes, R. E. (2006). Parental correlates of physical activity in children and early adolescents. Sports Medicine, 36(1), 79–97.

Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M., & Bull, F. C. (2020). Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2.

Harrington, D. M., Gillison, F., Broyles, S. T., Chaput, J. P., Fogelholm, M., & Hu, G., et al. (2016). Household-level correlates of children’s physical activity levels in and across 12 countries. Obesity, 24(10), 2150–2157. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21618.

Hoyle, R. H. (1995). Basic concepts and fundimental issues. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling concepts, issues and applications (pp. 1–15). Sage.

Hutchens, A., & Lee, R. E. (2018). Parenting practices and children’s physical activity: An integrative review. Journal of School Nursing, 34(1), 68–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840517714852.

Jaeschke, L., Steinbrecher, A., Luzak, A., Puggina, A., Aleksovska, K., & Buck, C., et al. (2017). Socio-cultural determinants of physical activity across the life course: A ‘Determinants of Diet and Physical Activity’ (DEDIPAC) umbrella systematic literature review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0627-3.

Jago, R., Davison, K. K., Brockman, R., Page, A. S., Thompson, J. L., & Fox, K. R. (2011). Parenting styles, parenting practices, and physical activity in 10- to 11-year olds. Preventive Medicine, 52(1), 44–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.001.

Kessler, R. C., & Greenberg, D. F. (1981). Linear panel analysis: Models of quantitative change. Academic Press.

Lau, E. Y., Faulkner, G., Qian, W., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2016). Longitudinal associations of parental and peer influences with physical activity during adolescence: Findings from the COMPASS study. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 36(11), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.36.11.01.

Love, R., Adams, J., & van Sluijs, E. M. F. (2019). Are school-based physical activity interventions effective and equitable? A meta-analysis of cluster randomized controlled trials with accelerometer-assessed activity. Obesity Reviews, 20(6), 859–870. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12823.

Matos, R., Monteiro, D., Amaro, N., Antunes, R., Coelho, L., Mendes, D., et al. (2021). Parents’ and Children’s (6-12 years old) physical activity association: A systematic review from 2001 to 2020. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312651.

Merlo, C. L., Jones, S. E., Michael, S. L., Chen, T. J., Sliwa, S. A., & Lee, S. H., et al. (2020). Dietary and physical activity behaviors among high school students—Youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a8.

Metcalf, B., Henley, W., & Wilkin, T. (2012). Effectiveness of intervention on physical activity of children: Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials with objectively measured outcomes (EarlyBird 54). BMJ, 345, e5888. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5888.

Morgan, P. J., Rayward, A. T., Young, M. D., Pollock, E. R., Eather, N., & Barnes, A. T., et al. (2022). Establishing effectiveness of a community-based, physical activity program for fathers and daughters: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 56(7), 698–711. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaab056.

Orehek, E., & Ferrer, R. (2019). Parent instrumentality for adolescent eating and activity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 53(7), 652–664. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kay074.

Pate, R. R., Dowda, M., Dishman, R. K., Colabianchi, N., Saunders, R. P., & McIver, K. L. (2019a). Change in children’s physical activity: Predictors in the transition from elementary to middle school. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(3), e65–e73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.012.

Pate, R. R., Schenkelberg, M. A., Dowda, M., & McIver, K. L. (2019b). Group-based physical activity trajectories in children transitioning from elementary to high school. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 323 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6630-7.

Petersen, T. L., Moller, L. B., Brond, J. C., Jepsen, R., & Grontved, A. (2020). Association between parent and child physical activity: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 67 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-00966-z.

Pfeiffer, K. A., Dowda, M., McIver, K. L., & Pate, R. R. (2009). Factors related to objectively measured physical activity in preschool children. Pediatric Exercise Science, 21(2), 196–208.

Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. (2018). 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee scientific report. US DHHS.

Rhodes, R. E., Guerrero, M. D., Vanderloo, L. M., Barbeau, K., Birken, C. S., & Chaput, J. P., et al. (2020a). Development of a consensus statement on the role of the family in the physical activity, sedentary, and sleep behaviours of children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-00973-0.

Rhodes, R. E., Perdew, M., & Malli, S. (2020b). Correlates of parental support of child and youth physical activity: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 27(6), 636–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09909-1.

Rhodes, R. E., & Quinlan, A. (2014). The family as a context for physical activity promotion. In M. R. Beauchamp & M. A. Eys (Eds.), Group dynamics in exercise and sport psychology. Routledge.

Rhodes, R. E., Spence, J. C., Berry, T., Deshpande, S., Faulkner, G., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E., et al. (2015). Predicting changes across 12 months in three types of parental support behaviors and mothers’ perceptions of child physical activity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49(6), 853–864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9721-4.

Rodrigues, D., Padez, C., & Machado-Rodrigues, A. M. (2018). Active parents, active children: The importance of parental organized physical activity in children’s extracurricular sport participation. Journal of Child Health Care, 22(1), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493517741686.

Sallis, J. F., Taylor, W. C., Dowda, M., Freedson, P. S., & Pate, R. R. (2002). Correlates of vigorous physical activity for children in grades 1 through 12: Comparing parent-reported and objectively measured physical activity. Pediatric Exercise Science, 14(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.14.1.30.

Trost, S. G., Sallis, J. F., Pate, R. R., Freedson, P. S., Taylor, W. C., & Dowda, M. (2003). Evaluating a model of parental influence on youth physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25(4), 277–282.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018). Physical activity guidelines for Americans (2nd ed.). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/.

United States Census Bureau. (2010). State and county quick facts: York and Sumter Counties, SC.

Wilk, P., Clark, A. F., Maltby, A., Tucker, P., & Gilliland, J. A. (2018). Exploring the effect of parental influence on children’s physical activity: The mediating role of children’s perceptions of parental support. Preventive Medicine, 106, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.10.018.

Yao, C. A., & Rhodes, R. E. (2015). Parental correlates in child and adolescent physical activity: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0163-y.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the children and parents who participated in the study, the staff of the Children’s Physical Activity Research Group who collected the data, and Gaye Groover Christmus, MPH, University of South Carolina, who edited the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01HL091002). The funding agency was not involved in the design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Open access funding provided by the Carolinas Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ruth P. Saunders: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, review and editing. Marsha Dowda: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Rod K. Dishman: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, validation, writing—review and editing. Russell R. Pate: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The Institutional Review Board at the University of South Carolina approved the protocols.

Informed Consent

Parent/guardian consent and child assent were obtained prior to data collection.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saunders, R.P., Dowda, M., Dishman, R.K. et al. A Longitudinal Examination of Direct and Indirect Influences of Parental Behaviors on Child Physical Activity. J Child Fam Stud 33, 2262–2270 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02830-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02830-1