Abstract

Kappaphycus alvarezii is a large commercial tropical marine red alga. In this study we used next-generation sequencing to determine the complete plastid genome of K. alvarezii. The plastid genome mapped a 178,205-bp circular DNA molecule with a GC content of 29.6%, without any inverted repeat region, and encoded a standard set of 202 protein-coding genes, including 4 open reading frames, 30 transfer RNA genes, 3 ribosomal RNA genes, and 1 transfer-messenger RNA gene. Only one group II intron interrupting the trnMe gene was detected. Comparative analysis of the seven plastid genomes from three orders including Gigartinales, Gracilariales, and Peyssonneliales revealed that the genomes were more conserved except five remarkable gene rearrangements. However, an approximately 12.5-kb gene fragment from the psaM to ycf21 gene in K. alvarezii plastid genome was completely reversed compared to that in published plastid genomes from the Florideophyceae. To our knowledge, the gene rearrangement was identified for the first time in the plastid genomes of red algal species. In addition, phylogenetic analysis of 49 Florideophyceae species based on 144 shared protein-coding genes suggested that different species from the same class clustered together according to their sources: three species of Gigartinales formed one group as the subbranch of Florideophyceae, but K. alvarezii was the most closely related to Riquetophycus sp. from the Peyssonneliales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Kappaphycus alvarezii (Solieriaceae, Rhodophyta) is a large tropical red seaweed which is an important raw material to extract carrageenan; it is mainly cultivated in Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines (Bindu and Levine 2011; Hurtado et al. 2015). Because of its important economic value in the food and carrageenan industry and the relatively simple aquaculture (seeding breeding mainly via vegetative reproduction), large-scale cultivation of K. alvarezii has expanded to tropical and subtropical countries, including Malaysia, Fiji, Vietnam, Tanzania, and South Africa (Hurtado et al. 2014; Msuya et al. 2014). In the 1980s, K. alvarezii was first introduced to China for culture (Wu et al. 1988). At present, large-scale farming of K. alvarezii is performed in the sea areas of Hainan Province of Southern China and K. alvarezii has become an important seaweed resource in China.

In recent years, studies focusing on K. alvarezii have gradually increased. K. alvarezii is a good seaweed resource that can be used as a raw material to produce renewable biofuel. Previous studies showed that extracting bioethanol from the acid hydrolysate of the carrageenophyte K. alvarezii was possible (Khambhaty et al. 2012; Meinita et al. 2012, 2019). However, several species of Kappaphycus are considered to be invasive algae that can grow rapidly throughout the reef habitats and kill corals (Conklin and Smith 2005; Chandrasekaran et al. 2008). Most studies have generally focused on the maximum utilization of Kappaphycus with regard to its culture, including growth rate experiments and protoplast culture (Hayashi et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2014). However, little information is available on the molecular biology of K. alvarezii. Existing studies involved only in markers for barcoding, species delimitation, and molecular phylogenetic analyses based on single gene sequence, such as plastid rbcL, mitochondrial cox1, nuclear ITS, and 28S rRNA (Conklin et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2014). At present, plastid genomes from Solieriaceae have been rarely explored. Further, the complete plastid genomes of only Chondrus crispus (NC_020795) and Mastocarpus papillatus (NC_031167) from Gigartinales order are available (Janoukovec et al. 2013; Sissini et al. 2016). Conducting detailed molecular systematic researches on red algae of Solieriaceae family and phylogenetic analysis at the whole plastid genome level might provide more comprehensive and accurate data to clarify the evolution of plastids.

With the development of high-throughput sequencing technologies, whole genome sequencing projects have been established for numerous species. Organelle genomes of mitochondrion and plastid are small in size and have relatively compact structure; thus, obtaining the whole genomes in a short time is usually possible. In this study, we obtained the red algae plastid genome pool by sequencing the large marine red alga K. alvarezii. The data represented the first completely characterized plastid genome from the species belonging to Solieriaceae. By conducting comparative analysis of plastid genomes of six red algal species from Florideophyceae, we explored the changes in the characteristics of plastid genome structure during the evolution of these species. Further, we provided new molecular data that might form a basis for phylogenetic studies on tropical red algae as well as comparative genomics of Solieriaceae species.

Materials and methods

Sampling and DNA extraction

Kappaphycus alvarezii was collected from Lingshui County, Hainan Province of China. Algal material was deposited in the Culture Collection of Seaweed at the Ocean University of China in Qingdao (sample number: 2012040002). Fresh alga was cultivated at 24 °C in sterilized seawater with nutrients (4 mg L−1 NaNO3, 0.4 mg L−1 KH2PO4) under fluorescent light (~ 40.5 μmol photons m−2 s−1; 12 h light/dark cycles). The alga was thoroughly cleaned with sterilized seawater before extracting DNA. Total DNA was extracted from fresh alga according to a modified CTAB method (Doyle and Doyle 1990). The quality and quantity of extracted DNA were determined using a NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.).

Genome sequencing and assembly

DNA library sequencing and construction were performed by the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) in Shenzhen, China. We used approximately 5 μg of purified DNA for the construction of short-insert libraries following manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina Inc., USA). The sequenced libraries included short pair-end libraries with insert lengths of 250, 300, and 500 bp. The constructed DNA library was extracted using the Illumina Hiseq 2000 system.

The raw reads were assembled into contigs by using SOAPdenovo software (Luo et al. 2012) with default assembly parameters (SOAPde-novo all –s assembly.conf –o mysample –k 49 –p 8&). The proportion of plastid-related contigs was determined using the plastid genome of Chondrus crispus (NC_020795) as reference sequence by using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) software (Altschul et al. 1997). Subsequently, all plastid-related contigs were aligned and ordered into a circular structure by using CodonCode Aligner software (CodonCode Corporation, USA). Gaps between contigs were filled using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Sanger sequencing by using the primers listed in Table S1, until the complete circular sequence was obtained. For junction regions between rearranged segments, additional primers (Table S1) were designed to ensure the accuracy of the sequence by conducting PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Annotation and comparative analysis

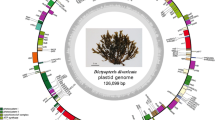

The protein-coding, ribosomal RNA (rRNA), intron and transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA) genes of the assembled plastid genome were determined by sequence alignment with the corresponding plastid genome of C. crispus by using Geneious R 10 (Biomatters Ltd., New Zealand; available from http://www.geneious.com/). To detect the open reading frames (ORFs), we used NCBI ORF-finder, and alignments were conducted using BLASTX searches at NCBI. Transfer RNA (tRNA) genes were predicted using tRNAscan-SE 1.21 software (Lowe and Eddy 1997). The plastid genome map of K. alvarezii was obtained using Organellar Genome OGDRAW software (Lohse et al. 2007). The plastid genomes of seven species from Florideophyceae class were compared using the multiple genome alignment software MAUVE (Darling et al. 2004).

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using 144 conserved plastid protein-coding genes from 50 red algal plastid genomes publicly available at the NCBI GenBank (including our one new plastid genome). Every gene was found in all taxa (50 species); some protein-encoding genes previously reported as missing were reannotated in this study (Table S2). Each protein sequence was aligned individually by using MEGA 5.0 software (Tamura et al. 2011), and then the entire concatenated alignment was generated and edited manually using BioEdit software (Hall 1999). The Gblocks server (http://molevol.cmima.csic.es/castresana/Gblocks_server.html; Castresana 2000) was used to generate concatenated alignments and remove poorly aligned regions, resulting in the alignment reducing from 36,690 to 29,175 position. To reconstruct the phylogenetic tree, the best-fit model for maximum likelihood (ML) was selected using ProtTest 3.4.2 (Darriba et al. 2011). ML search and ML bootstrap analysis were performed using RAxML (Stamatakis 2006) with 1000 replications under the CpREV + G + I + F model. The Bayesian tree (BI) was conducted using MrBayes v. 3. 1.2 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001). Bayesian analysis was performed using two separate sequence analyses for four Markov chains (by using default heating values), which were run for 2,000,000 generations until the average standard deviation of split frequencies was below 0.01 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003). In addition, the first 25% of trees were discarded as burn-in. The remaining trees were used to build a 50% majority rule consensus tree, accompanied with posterior probability values. FigTree v1.3.1 software was used to display and edit the phylogenetic tree (Rambaut 2009).

Results

Structure and features of the plastid genome

The complete plastid genome of K. alvarezii, sequenced using next-generation sequencing (NGS) method, was assembled as a circular molecule of 178,205 bp in length with an overall A + T content of 70.44%; the nucleotide composition was 34.92% A, 14.83% C, 14.74% G, and 35.52% T (GenBank accession number; KU892652). No inverted repeat (IR) region was identified in K. alvarezii. IR was described in most of the early-diverged classes (Bangiophyceae), whereas most Florideophycean species found merely single or partially inactivated (pseudogenes) duplicated rDNAs. The plastid genome of K. alvarezii encoded 202 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNA genes, 3 rRNA genes, and 1 tmRNA gene; only one group II intron (with intronic ORF436) interrupting the trnMe gene was detected (Fig. 1; Table 1). The similarity of intronic ORF436 between K. alvarezii and C. crispus was 49.89% based on amino acid sequence alignment using MEGA 5.0 software (Fig. S1). And the published plastid genomes of red algae suggested that the intronic ORFs of all Florideophyceae species were a homologous group derived from prokaryotes (Lee et al. 2016). The coding region was 145,809 bp, accounting for 81.82% of the total genome. The tRNA sequences ranged from 71 to 89 bp, and most of the tRNA genes had the standard cloverleaf secondary structures (Fig. S2). All genes were encoded on both the heavy and light strands.

Kappaphycus alvarezii plastid genome had three types of start codons (Table S3). ATG was used as the start codon for nearly all plastid genes (94%), whereas TTG was used as the start codon for the ycf20, ycf27, and trxA genes. In addition, many plastid genes (including psbC, rps8, rpl24, rpl3, petN, rbcS, infC, chlI, ycf63, and ycf64) used GTG as the start codon. Three typical types of stop codons were noted for K. alvarezii plastid genes: TAA, TAG, and TGA (Table S3). Of these, the predominant codon was TAA with the highest proportion of 70.3%; TGA and TAG also accounted for a considerable proportion of 10.4% and 19.3%, respectively. In addition, the plastid genome of K. alvarezii was compact; ten pairs of gene overlaps with overlap length of 1–26 bp (carA-ycf53, ccs1-trpG, ycf60-rps6, psbD-psbC, ORF146-groEL, trnH-ycf29, rpl24-rpl14, rpl23-rpl4, atpF-atpD, and psaL-trnT) were found.

Comparative genome analysis and gene rearrangement

Kappaphycus alvarezii as well as C. crispus and Mastocarpus papillatus belong to the same order of Gigartinales; the overall gene content and structure of K. alvarezii plastid genome were nearly the same as those of the plastid genomes of C. crispus and M. papillatus (Table 1). However, global plastid genome comparison indicated some remarkable differences among different Gigartinales species as follows: the dfr gene was present in K. alvarezii and M. papillatus between the ycf63 and psbE genes, but not in C. crispus. Further, interestingly, the pbsA gene was absent between the bas1 and rpl35 genes in K. alvarezii, as well as in M. papillatus, but not in C. crispus; this gene was commonly found in other red algal plastid genomes of Florideophyceae and Bangiophyceae species. However, a fragment of similar length was still found at the original location of the pbsA gene, which had a low homology of 62.5% with the pbsA gene from C. crispus (Fig. 2). Several stop codons were produced ahead of time in the fragment, probably because of many base mutations at different sites, or perhaps because a frameshift by one base mutation caused multiple stop codons downstream of the shifting point. Obtaining an effective length of the ORF was not possible in this study, although we attempted to shift the reading frame or change the transcriptional direction. Therefore, we speculated that the pbsA gene was absent in the plastid genome of K. alvarezii. In addition, notably, a gene cluster containing 16 genes of about 12.5 kb in length from the psaM to ycf21 genes in the K. alvarezii plastid genome was completely reversed compared to that from C. crispus and M. papillatus. The junction regions related to the fragment were verified by PCR and Sanger sequencing by using primers listed in Table S1. The gene fragment having the same gene content and order was located at the same position in the plastid genome, but in a different transcriptional direction (Fig. 3).

Plastid genome comparison among seven red algal species from Florideophyceae by using MAUVE. Color box below the line has an inverse orientation relative to Kappaphycus alvarezii. Letters A, B, C, D and E represent three inverted fragments among seven species, respectively, in which the fragment E in K. alvarezii is unique compared with that in the other six species

Comparison of three plastid genomes from Gigartinales, one known plastid genome of Riquetophycus sp. from Peyssonneliales and three previously sequenced species from Gracilariales, including Gracilaria salicornia, Gracilaria tenuistipitata var. liui and Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis, revealed significant synteny. The overall sequences of the red algal plastid genomes were found to be fairly conserved, with similar gene content and genome organization. However, global plastid genome comparison by using MAUVE alignment indicated a large number of rearrangements among different species (Fig. 3). Five reversed fragments were detected between seven Florideophyceae species, corresponding to the regions marked with A, B, C, D, and E in Fig. 3, with fragment lengths of about 18.5 kb (ycf46–trnN), 4.6 kb (ccdA-rps6), 10.5 kb (psb28-rpl9), 4.4 kb (dnaB-clpC), and 12.5 kb (ycf21-psaM), respectively. These reversed fragments showed the following characteristics: (1) long conserved gene clusters with almost the same gene content and order; (2) same location in the plastid genome structure; and (3) reversal of fragment, indicating that the transcriptional orientation of the entire fragment had changed.

Phylogenetic analysis

Based on the previously published plastid genomes of Florideophyceae, including 49 species, we used a common dataset of 144 protein-coding genes to conduct phylogenetic analysis; C. merolae was used as an outgroup. The ML and BI phylogenetic trees with very high posterior probabilities are shown in Fig. 4. The results revealed that the Florideophyceae taxa were clearly separated into 20 orders. Although the phylogenetic relationship obtained in this study was similar with the one revealed by Lee et al. (2016), it reconducted the phylogenetic relationship in the order Gigartinales. Three species from Gigartinales and one from Peyssonneliales formed a clade. Within this clade, C. crispus showed a closer relationship with M. papillatus; however, K. alvarezii was included in a strongly supported clade with Riquetophycus sp., which belonged to Peyssonneliales.

ML and BI phylogenetic trees generated using 144 concatenated plastid protein-coding genes from 49 Florideophyceae species. Cyanidioschyzon merolae was set as an outgroup; the support values for each node are shown from maximum likelihood bootstrap and Bayesian posterior probabilities. Asterisk indicates newly sequenced Kappaphycus alvarezii in this study

Discussion

The plastid genomes of Florideophyceae species were conserved in gene content and genome structure except Hildenbrandiales (Lee et al. 2016). The plastid genome of K. alvarezii was fairly conserved, with similar gene content and number. However, the plastid genome size differed among the Florideophyceae species: the average length was 181 kb, and average AT content was 70.71%. The plastid genome size of K. alvarezii was the smallest among those of Gigartinales species. The three members of Gigartinales consisted of one group II intron, interrupting trnMe gene (Table 1). Within Florideophyceae species, it was found to contain one intron or two introns encoding maturase ORF (RT/mat) (Janoukovec et al. 2013). For example, Calliarthron tuberculosum additionally contained a second group II intron in chlB, except one group II intron in trnMe. It was likely that Florideophyceae species should have two introns in chlB and trnMe, while chlB intron or trnMe intron had been missed in some Florideophyceae plastid genomes during the time of Florideophyceae divergence; only a handful of species had been able to retained both two.

In the plastid genomes of red algae, in addition to ATG, TTG and GTG also served as initiation codons. TTG was a rare alternative initiation codon in organisms known to use a non-standard genetic code. In bacteria, in addition to the standard start codon ATG, the triplets GTG, ATT, and TTG serve as start codons (Golderer et al. 1995). A previous study showed that TTG was the start codon for the tatC gene from the mitochondrial genome of Kappaphycus striatus (Tablizo and Lluisma 2014). In addition to TTG, GTG was also occasionally used as the start codon in K. alvarezii. Analysis of brown algal plastid genomes revealed that several genes used GTG as the start codon (Corguille et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2013). Additionally, as a red algae plastid descendant, a few brown algal species also used ATT as a start codon (Zhang et al. 2015a, b). However, TTG as a start codon was noted only in the plastid genomes of red algal species.

One of the most remarkable characteristics in K. alvarezii was the absence of the pbsA gene. Analysis of the published plastid genomes of Gigartinales species showed that the pbsA gene was absent in K. alvarezii and M. papillatus. In algae, the pbsA gene was homologous with the heme oxygenase (HO) gene for phycobilin synthesis (Reith and Munholland 1995). HO is a key enzyme in the synthesis of the chromophoric part of the photosynthetic antennae in cyanobacteria, red algae, and Cryptophyceae. Richaud and Zabulon (1997) cloned and sequenced the pbsA gene from the chloroplast genome of red alga Rhodella violacea and found that it was split into three distant exons. No large insertion was noted at the assumed region of the pbsA gene; therefore, it probably did not contain any intron. The loss of gene function should have been caused by base mutation. In the present study, the pbsA gene was encoded in most red algal plastid genomes, and the phylogenetic data suggested pbsA gene was derived from cyanobacteria, while the loss of pbsA gene in red algal plastids was rare and a stochastic process, probably because the gene played an unnecessary role. Furthermore, it has been found that some red algal species presented three heme oxygenase genes; two nuclear-encoded heme oxygenase types, HMOX1and HMOX2; and pbsA gene in plastid genome (Costa et al. 2016; Cho et al. 2018).

MAUVE analysis from seven species showed that the gene content and order of the three plastid genomes of G. salicornia, G. tenuistipitata var. liui, and G. lemaneiformis from the order Gracilariales were almost completely consistent. Nonetheless, K. alvarezii, M. papillatus, and C. crispus from Gigartinales order and Riquetophycus sp. from the Peyssonneliales order showed marked differences compared with those in the three species of order Gracilariales. In Riquetophycus sp., there are two long and conserved gene clusters, in which the gene order was almost exactly the same (areas A and B in Fig. 3) and completely reversed compared with other species. Similar to Riquetophycus sp., two gene clusters (areas C and D in Fig. 3) from the three Gracilariales species were reversed compared with those in the three Gigartinales species and one Peyssonneliales species. Interestingly, whereas in K. alvarezii, another gene cluster (area E in Fig. 3) was reversed compared to that in the other six species, and this region was unique based on comparison with the Florideophyceae plastid genomes published in the NCBI dataset. Therefore, the rearranged fragments of K. alvarezii from Solieriaceae were identified for the first time in the plastid genomes of red algae. Thus, the results showed that red algal plastid genomes included four rearrangements between those three orders, with the feature of a large conserved gene cluster reversed at the same location. Only in this study, for Florideophyceae, including seven species from three different orders, a total of five long reversed fragments were detected; furthermore, such rearrangements not only occurred between species from different orders but were also noted at the family level. Usually, gene rearrangements such as reordering of genetic elements occur via repeated inversion. However, no similar structures such as inverted sequences were found at the junction area between these rearranged fragments and adjacent to the relevant region, or any common feature was not determined between these fragments. The detailed mechanism of these rearrangements will warrant further analysis.

The phylogenetic analysis did not well supported the previous observation of the evolutionary process of the class Florideophyceaen, either we added plastid genome of newly sequenced specie, K. alvarezii; the result reconstructed the phylogenetic relationship in Gigartinales. Our phylogenetic analysis suggested that the Florideophyceaen species, except Hildenbrandiophycidae (Hildenbrandia rivularis, Hildenbrandia rubra, and Apophlaea sinclairii), formed a tight group, in which the Florideophyceae taxa were clearly separated into different groups corresponding to their subclass (Nemaliophycidae, Corallinophycidae, Ahnfeltiophycidae and Rhodymeniophycidae). However, three species from the order Gigartinales and Riquetophycus sp. from Peyssonneliales clustered as a subbranch in a large branch of the subclass Rhodymeniophycidae, consistent with the findings for M. papillatus described in the phylogenetic analysis of Florideophyceaen mitogenomes (Sissini et al. 2016). Addition of the newly sequenced specie K. alvarezii revealed that K. alvarezii had a closer relationship with Riquetophycus sp., whereas C. crispus and M. papillatus formed another cluster within the Gigartinales order.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, the complete plastid genome of K. alvarezii from Gigartinales was determined for the first time in this study. Comparative analysis indicated that a new gene rearrangement was observed in the K. alvarezii plastid genome, with the complete reversion of an approximately 12.5 kb gene fragment from the psaM to ycf21 genes, unlike that in other published Florideophyceae plastid genomes. Moreover, inclusion of a new species helped in the reconstruction of the phylogenetic relationship of Florideophyceae species, in which K. alvarezii was found to have a closer relationship with Riquetophycus sp. from the Peyssonneliales. Additionally, the plastid genome of K. alvarezii could be of significance for studies on evolutionary relationship among red algal species.

Change history

04 November 2019

The original version of this article unfortunately contained a mistake

References

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402

Bindu MS, Levine IA (2011) The commercial red seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii—an overview on farming and environment. J Appl Phycol 23:789–796

Castresana J (2000) Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 17:540–552

Chandrasekaran S, Nagendran NA, Pandiaraja D, Krishnankutty N, Kamalakannan B (2008) Bioinvasion of Kappaphycus alvarezii on corals in the Gulf of Mannar, India. Curr Sci 94:1167–1172

Cho CH, Choi JW, Lam DW, Kim KM, Yoon HS, Devarenne TP (2018) Plastid genome analysis of three Nemaliophycidae red algal species suggests environmental adaptation for iron limited habitats. PLoS One 13:e0196995

Conklin EJ, Smith JE (2005) Abundance and spread of the invasive red algae, Kappaphycus spp., in Kane’ohe Bay, Hawai’i and an experimental assessment of management options. Biol Invas 7:1029–1039

Conklin KY, Kurihara A, Sherwood AR (2009) A molecular method for identification of the morphologically plastic invasive algal genera Eucheuma and Kappaphycus (Rhodophyta, Gigartinales) in Hawaii. J Appl Phycol 21:691–699

Corguille GL, Pearson G, Valente M, Viegas C, Gschloessl B, Corre E (2009) Plastid genomes of two brown algae, Ectocarpus siliculosus and Fucus vesiculosus: further insights on the evolution of red-algal derived plastids. BMC Evol Biol 9:253

Costa FJ, Lin SM, Macaya EC, Fernández-García C, Verbruggen H (2016) Chloroplast genomes as a tool to resolve red algal phylogenies: a case study in the Nemaliales. BMC Evol Biol 16:205

Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT (2004) Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res 14:1394–1403

Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D (2011) ProtTest 3: fast selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics 27:1164–1165

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL (1990) Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12:13–15

Golderer G, Dlaska M, Gröbner P, Piendl W (1995) TTG serves as an initiation codon for the ribosomal protein MvaS7 from the archaeon Methanococcus vannielii. J Bacteriol 177:5994–5996

Hall TA (1999) BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. In: Nucleic acids symposium series, pp 95–98

Hayashi L, de Paula EJ, Chow F (2007) Growth rate and carrageenan analyses in four strains of Kappaphycus alvarezii (Rhodophyta, Gigartinales) farmed in the subtropical waters of São Paulo State, Brazil. J Appl Phycol 19:393–399

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F (2001) Mrbayes: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17:754–755

Hurtado AQ, Gerung GS, Yasir S, Critchley AT (2014) Cultivation of tropical red seaweeds in the BIMP-EAGA region. J Appl Phycol 26:707–718

Hurtado AQ, Neish IC, Critchley AT (2015) Developments in production technology of Kappaphycus in the Philippines: more than four decades of farming. J Appl Phycol 27:1945–1961

Janoukovec J, Liu SL, Martone PT, Carr W, Leblanc C, Colln J, Keeling PJ (2013) Evolution of red algal plastid genomes: ancient architectures, introns, horizontal gene transfer, and taxonomic utility of plastid markers. PLoS One 8:e59001

Khambhaty Y, Mody K, Gandhi MR, Thampy S, Maiti P, Brahmbhatt H (2012) Kappaphycus alvarezii as a source of bioethanol. Bioresour Technol 103:180–185

Lee JM, Cho CH, Park SI, Ji WC, Song HS, West JA, Debashish B, Hwan SY (2016) Parallel evolution of highly conserved plastid genome architecture in red seaweeds and seed plants. BMC Biol 14:75

Liu T, Sun Y, Jin YM, Liu C, Zhang L, Zhang S (2012) Study on molecular systematics of four seaweed species in family Solieriaceae (Rhodophyta). J Ocean Univ China 42:39–48

Lohse M, Dreshsil O, Bock R (2007) OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW): a tool for the easy generation of high–quality custom graphical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Curr Genet 52:267–264

Lowe TM, Eddy SR (1997) tRNAscan–SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 25:955–964

Luo R, Liu B, Xie Y, Li Z, Huang W, Yuan J (2012) SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. GigaScience 1:18

Meinita MDN, Kang JY, Jeong GT, Koo HM, Park SM, Hong YK (2012) Bioethanol production from the acid hydrolysate of the carrageenophyte Kappaphycus alvarezii (cottonii). J Appl Phycol 24:857–862

Meinita MDN, Marhaeni B, Jeong G-T, Hong Y-K (2019) Sequential acid and enzymatic hydrolysis of carrageenan solid waste for bioethanol production: a biorefinery approach. J Appl Phycol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-019-1755-8

Msuya FE, Buriyo A, Omar I, Pascal B, Narrain K, Ravina JJM, Mrabu E, Wakibia JG (2014) Cultivation and utilisation of red seaweeds in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO) region. J Appl Phycol 26:699–705

Rambaut A (2009) FigTree v1.3.1. 2006–2009. Program package available at http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/. Accessed 29 Nov 2012

Reith M, Munholland J (1995) Complete nucleotide sequence of the Porphyra purpurea chloroplast genome. Plant Mol Biol Rep 13:333–335

Richaud C, Zabulon G (1997) The heme oxygenase gene (pbsA) in the red alga Rhodella violacea is discontinuous and transcriptionally activated during iron limitation. P Natl Acad Sci USA 94:11736–11741

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP (2003) MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19:1572–1574

Sissini MN, Navarretefernández TM, Murray EMC, Freese JM, Gentilhomme AS, Huber SR (2016) Mitochondrial and plastid genome analysis of the heteromorphic red alga Mastocarpus papillatus (C. Agardh) Kützing (Phyllophoraceae, Rhodophyta) reveals two characteristic florideophyte organellar genomes. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 1:676–677

Stamatakis A (2006) RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22:2688–2690

Sun Y, Liu C, Chi S, Tang XM, Chen FX, Liu T (2014) Molecular systematic of four Solieriaceae algae based on ITS and rbcL sequence. J Ocean Univ China 44:54–60

Tablizo FA, Lluisma AO (2014) The mitochondrial genome of the red alga Kappaphycus striatus (“Green Sacol” variety): complete nucleotide sequence, genome structure and organization, and comparative analysis. Mar Genom 18:155–161

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S (2011) MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28:2731–2739

Wang X, Shao Z, Fu W, Yao J, Hu Q, Duan D (2013) Chloroplast genome of one brown seaweed, Saccharina japonica (Laminariales, Phaeophyta): its structural features and phylogenetic analyses with other photosynthetic plastids. Mar Genom 10:1–9

Wu CY, Li JJ, Xia EZ, Peng ZS, Tan SZ, Li J (1988) Transplant and artificial cultivation of Eucheuma striatum in China. Oceanol Limnol Sinica 19:410–417

Zhang S, Liu C, Jin YM, Chi S, Tang XM, Chen FX (2014) Studies on the isolation and culture of protoplasts from Kappaphycus alvarezii. Acta Oceanol Sinica 33:114–123

Zhang L, Wang X, Liu T, Wang G, Chi S, Liu C, Wang HY (2015a) Complete plastid genome sequence of the brown alga Undaria pinnatifida. PLoS One 10:e0139366

Zhang L, Wang X, Liu T, Wang H, Wang G, Chi S, Liu C (2015b) Complete plastid genome of the brown alga Costaria costata (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae). PLoS One 10:e0140144

Funding

This work was funded by the China-ASEAN Maritime Cooperation Fund and the Public Science and Technology Research Funds Projects of Ocean (Grant No. 201405020), and also supported by Center for Maritime Biosciences Studies, Institute for Research and Community Service, Jenderal Soedirman University, Purwokerto, Indonesia .

This work was also supported by the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of theRepublic Indonesia through International Collaboration Research Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Table S1

Sequences of the primers designed for gap filling and assembly validation (PDF 52 kb)

Table S2

Characteristics of protein-coding genes in the Kappaphycus alvarezii plastid genome (202 total) (DOCX 19 kb)

Table S3

List of all Florideophyceae plastid genomes that were used to conduct the phylogenetic analysis. Protein coding genes previously reported as missing are listed with notes in this study (DOCX 32 kb)

Fig. S1

Amino acid sequence alignment of the intronic ORFORF436fromKappaphycus alvareziiwith that ofChondrus crispus. The same residues and similar residues were shown by a black box and a gray box, respectively (PNG 848 kb)

Fig. S2

The secondary structures of the 30 tRNA genes in the plastid genome of Kappaphycus alvarezii (DOCX 228 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, N., Zhang, L., Tang, X. et al. Complete plastid genome of Kappaphycus alvarezii: insights of large-scale rearrangements among Florideophyceae plastid genomes. J Appl Phycol 31, 3997–4005 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-019-01815-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-019-01815-8