Abstract

Existing research suggests that temperamental traits that emerge early in childhood may have utility for early detection and intervention for common mental disorders. The present study examined the unique relationships between the temperament characteristics of reactivity, approach-sociability, and persistence in early childhood and subsequent symptom trajectories of psychopathology (depression, anxiety, conduct disorder, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ADHD) from childhood to early adolescence. Data were from the first five waves of the older cohort from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (n = 4983; 51.2% male), which spanned ages 4–5 to 12–13. Multivariate ordinal and logistic regressions examined whether parent-reported child temperament characteristics at age 4–5 predicted the study child’s subsequent symptom trajectories for each domain of psychopathology (derived using latent class growth analyses), after controlling for other presenting symptoms. Temperament characteristics differentially predicted the symptom trajectories for depression, anxiety, conduct disorder, and ADHD: Higher levels of reactivity uniquely predicted higher symptom trajectories for all 4 domains; higher levels of approach-sociability predicted higher trajectories of conduct disorder and ADHD, but lower trajectories of anxiety; and higher levels of persistence were related to lower trajectories of conduct disorder and ADHD. These findings suggest that temperament is an early identifiable risk factor for the development of psychopathology, and that identification and timely interventions for children with highly reactive temperaments in particular could prevent later mental health problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Attrition in LSAC has been examined in detail elsewhere (Cusack and Defina 2013), and the bias in our study due to attrition was reduced by applying survey weights. However, these weights are based on demographic representativeness and do not necessarily account for differential drop-out with regard to the measures under investigation. As such, we analysed the symptom levels for each domain of psychopathology at Wave 1 for participants who dropped out of the study compared to participants who continued on to Wave 5. While there were no significant differences between the groups in symptom levels of anxiety, t(1871.44) = 0.28, p = 0.782; Cohen’s d < 0.01, or depression, t(1802.50) = 1.95, p = 0.052; Cohen’s d = 0.07, there were small but significant differences in symptoms of conduct disorder, t(1986.44) = 5.22, p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.17, and ADHD, t(2027.30) = 6.04, p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.20. In short, participants who dropped out tended to have higher externalizing symptoms on average, but the small effect sizes highlight that the two groups have more than 92% overlap in the distribution of these symptoms.

None of the scales used in the present study had excellent internal consistency. However, given the scales all represent abbreviated measures of complex constructs, we would expect moderate internal consistency at best, given the heterogeneous item content required to achieve content validity (i.e., substantial item specific variance) and the small number of items (i.e., two to five) included in each scale.

The use of standardised scales to represent the four domains of psychopathology at each time point highlights individuals’ relative symptom severity at each wave (i.e., the number of standard deviations away from the population mean), rather than absolute changes in symptom severity. This reflects a statistical deviation conceptualisation of psychopathology, and prevents population level age-related changes between waves from obscuring individual differences.

References

Beauchaine, T. P., & McNulty, T. (2013). Comorbidities and continuities as ontogenic processes: toward a developmental spectrum model of externalizing psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 25, (4pt2):1505–1528.

Belsky, J., & Pluess, M. (2009). Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 885–908.

Belsky, J., & Pluess, M. (2013) Beyond risk, resilience, and dysregulation: phenotypic plasticity and human development. Development and Psychopathology, 25, (4pt2):1243-1261.

Berlin, K. S., Parra, G. R., & Williams, N. A. (2014). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 2): longitudinal latent class growth analysis and growth mixture models. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 188–203.

Busseri, M. A., Willoughby, T., & Chalmers, H. (2006). A rationale and method for examining reasons for linkages among adolescent risk behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 279–289.

Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Newman, D. L., & Silva, P. A. (1996). Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53, 1033–1039.

Caspi, A., Houts, R. M., Belsky, D. W., Goldman-Mellor, S. J., Harrington, H., Israel, S., et al. (2014). The p factor one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 119–137.

Clauss, J. A., & Blackford, J. U. (2012). Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: a meta-analytic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 1066–1075.

Cole, D. A., Peeke, L. G., Martin, J. M., Truglio, R., & Seroczynski, A. D. (1998). A longitudinal look at the relation between depression and anxiety in children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 451.

Croft, S., Stride, C., Maughan, B., & Rowe, R. (2015). Validity of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in preschool-aged children. Pediatrics, 135, e1210–e1219.

Cusack, B., & Defina, R. (2013). The longitudinal study of Australian children technical paper no. 10: wave 5 weighting and non-response. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 483.

Degnan, K. A., Hane, A. A., Henderson, H. A., Moas, O. L., Reeb-Sutherland, B. C., & Fox, N. A. (2011). Longitudinal stability of temperamental exuberance and social-emotional outcomes in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 47, 765–780.

Else-Quest, N. M., Hyde, J. S., Goldsmith, H. H., & Van Hulle, C. A. (2006). Gender differences in temperament: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 33.

Forbes, M. K., Tackett, J. L., Markon, K. E., & Krueger, R. F. (2016). Beyond comorbidity: toward a dimensional and hierarchal approach to understanding psychopathology across the lifespan. Development and Psychopathology, 28, 971–986. doi:10.1017/S0954579416000651.

Glascoe, F. P. (2000). Parents’ evaluation of developmental status: authorized Australian version. Parkville: Centre for Community Child Health.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586.

Goodman, R., Ford, T., Simmons, H., Gatward, R., & Meltzer, H. (2000). Using the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 534–539.

Hallion, L. S., & Ruscio, A. M. (2011). A meta-analysis of the effect of cognitive bias modification on anxiety and depression. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 940–958.

Hane, A. A., Fox, N. A., Henderson, H. A., & Marshall, P. J. (2008). Behavioral reactivity and approach-withdrawal bias in infancy. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1491–1496.

Hankin, B. L., & Abramson, L. Y. (2001). Development of gender differences in depression: an elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 773–796.

He, J.-P., Burstein, M., Schmitz, A., & Merikangas, K. R. (2013). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ): the factor structure and scale validation in U.S. adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 583–595.

Heckman, J. J. (2012). The developmental origins of health. Health Economics, 21, 24–29.

Jung, T., & Wickrama, K. A. S. (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 302–317.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602.

Lahat, A., Hong, M., & Fox, N. A. (2011). Behavioural inhibition: is it a risk factor for anxiety? International Review of Psychiatry, 23, 248–257.

Lahey, B. B. (2004). Commentary: role of temperament in developmental models of psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 88–93.

Lahey, B. B., & Waldman, I. D. (2003). A developmental propensity model of the origins of conduct problems during childhood and adolescence. In B. B. Lahey, T. E. Moffitt, & A. Caspi (Eds.), Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency (pp. 76–117). New York: Guilford Press.

Lahey, B. B., & Waldman, I. D. (2005). A developmental model of the propensity to offend during childhood and adolescence. In D. P. Farrington (Ed.), Integrated developmental and life-course theories of offending (pp. 15–50). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Lahey, B. B., Applegate, B., Waldman, I. D., Loft, J. D., Hankin, B. L., & Rick, J. (2004). The structure of child and adolescent psychopathology: generating new hypotheses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 358.

Lahey, B. B., Applegate, B., Chronis, A. M., Jones, H. A., Williams, S. H., Loney, J., & Waldman, I. D. (2008). Psychometric characteristics of a measure of emotional dispositions developed to test a developmental propensity model of conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37, 794–807.

Lahey, B. B., Van Hulle, C. A., Singh, A. L., Waldman, I. D., & Rathouz, P. J. (2011). Higher-order genetic and environmental structure of prevalent forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68, 181–189.

Lahey, B. B., Zald, D. H., Hakes, J. K., Krueger, R. F., & Rathouz, P. J. (2014). Patterns of heterotypic continuity associated with the cross-sectional correlational structure of prevalent mental disorders in adults. JAMA Psychiatry, 71, 989–996.

Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., Boterhoven de Haan, K., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents: report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health.

Letcher, P., Smart, D., Sanson, A., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2009). Psychosocial precursors and correlates of differing internalizing trajectories from 3 to 15 years. Social Development, 18, 618–646.

Leve, L. D., Kim, H. K., & Pears, K. C. (2005). Childhood temperament and family environment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing trajectories from ages 5 to 17. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 505–520.

Little, P. T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

McClowry, S. G. (2002). The temperament profiles of school-age children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 17, 3–10.

Mesman, J., Stoel, R., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van IJzendoon, M., Juffer, F., Koot, H., & Lenneke, R. A. (2009). Predicting growth curves of early childhood externalising problems: differential susceptiblity of children with difficult temperament. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 37, 625–636.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Blijlevens, P. (2007). Self-reported reactive and regulative temperament in early adolescence: relations to internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and “big three” personality factors. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 1035–1049.

Nigg, J. T., Goldsmith, H. H., & Sachek, J. (2004). Temperament and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: the development of a multiple pathway model. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 42–53.

Oberklaid, F. (2000). Editorial comment. Persistent crying in infancy: a persistent clinical conundrum. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 36, 297–298.

O’Donnell, K. J., Glover, V., Barker, E. D., & O’Connor, T. G. (2014). The persisting effect of maternal mood in pregnancy on childhood psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 393–403.

Oldehinkel, A. J., Hartman, C. A., De Winter, A. F., Veenstra, R., & Ormel, J. (2004). Temperament profiles associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in preadolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 421–440.

Ordway, M. R. (2011). Depressed mothers as informants on child behavior: methodological issues. Research in Nursing and Health, 34, 520–532.

Pluess, M., & Belsky, J. (2010). Children’s differential susceptibility to effects of parenting. Family Science, 1, 14–25.

Prior, M., Sanson, A., Smart, D., & Oberklaid, F. (2000a). Pathways from infancy to adolescence: Australian temperament project 1983–2000. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Prior, M., Smart, D., Sanson, A., & Oberklaid, F. (2000b). Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 461–468.

Putnam, S. P., & Stifter, C. S. (2002). Development of approach and inhibition in the first year. Parallel findings from motor behavior, temperament ratings, and directional cardiac responses. Developmental Science, 5, 441–451.

Putnam, S. P., Sanson, A. V., & Rothbart, M. K. (2002). Child temperament and parenting. Handbook of Parenting, 1, 255–277.

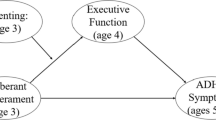

Rabinovitz, B. B., O’Neill, S., Rajendran, K., & Halperin, J. M. (2016). Temperament, executive control, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across early development. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125, 196–206.

Rapee, R. M. (2013). The preventative effects of a brief, early intervention for preschool-aged children at risk for internalising: follow-up into middle adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 780–788.

Rapee, R. M. (2014). Preschool environment and temperament as predictors of social and nonsocial anxiety disorders in middle adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 53, 320–328.

Rapee, R. M., Kennedy, S., Ingram, M., Edwards, S. L., & Sweeney, L. (2005). Prevention and early intervention of anxiety disorders in inhibited preschool children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 488–497.

Rettew, D. C., & McKee, L. (2005). Temperament and its role in developmental psychopathology. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 13, 14–27.

Rhee, S. H., Lahey, B. B., & Waldman, I. D. (2015). Comorbidity among dimensions of childhood psychopathology: converging evidence from behavior genetics. Child Development Perspectives, 9, 26–31.

Rothbart, M.K. (1989). Temperament and development. In G. A. Kohnstamm, J. E. Bates, & M. K. Rothbart (Eds.), Temperament in childhood (pp. 187-247). Chichester, England: Wiley.

Rothbart, M. K. (2007). Temperament, development, and personality. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 207–212.

Sanson, A., & Oberklaid, F. (2013). Infancy and early childhood. In The Australian Temperament Project: the First 30 Years. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Sanson, A., Prior, M., Oberklaid, F., Garino, E., & Sewell, J. (1987). The structure of infant temperament: factor analysis of the revised infant temperament questionnaire. Infant Behavior & Development, 10, 97–104.

Sanson, A., Pedlow, R., Cann, W., Prior, M., & Oberklaid, F. (1996). Shyness ratings: stability and correlates in early childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 19, 705–724.

Sanson, A., Hemphill, S. A., & Smart, D. (2004). Connections between temperament and social development: a review. Social Development, 13, 142–170.

Schwartz, C. E., Snidman, N., & Kagan, J. (1996). Early childhood temperament as a determinant of externalizing behavior in adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 527–537.

Shonkoff, J. P., & Fisher, P. A. (2013). Rethinking evidence based practice and two-generation programs to create the future of early childhood policy. Development and Psychopathology, 25, 1635–1653.

Smart, D., & Sanson, A. (2005). A comparison of children's temperament and adjustment across 20 years. Family Matters, 72, 50.

Smart, D., Hayes, A., Sanson, A., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2007). Mental health and wellbeing of Australian adolescents: pathways to vulnerability and resilience. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 19, 263–268.

Soloff, C., Lawrence, D., & Johnstone, R. (2005). Longitudinal study of Australian children technical paper no. 1: Sample design. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Sterba, S. K., Prinstein, M. J., & Cox, M. J. (2007). Trajectories of internalizing problems across childhood: heterogeneity, external validity, and gender differences. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 345–366.

Stifter, C. S., Putnam, S., & Jahromi, L. (2008). Exuberant and inhibited toddlers: stability of temperament and risk for problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 401–421.

Tackett, J. L., Lahey, B. B., van Hulle, C., Waldman, I., Krueger, R. F., & Rathouz, P. J. (2013). Common genetic influences on negative emotionality and a general psychopathology factor in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 1142–1153.

Thomas, A., & Chess, S. (1977). Temperament and development. Oxford: Brunner/Mazel.

Toumbourou, J. W., Williams, I., Letcher, P., Sanson, A., & Smart, D. (2011). Developmental trajectories of internalising behaviour in the prediction of adolescent depressive symptoms. Australian Journal of Psychology, 63, 214–223.

White, L. K., McDermott, J. M., Degnan, K. A., Henderson, H. A., & Fox, N. A. (2011). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety: the moderating roles of inhibitory control and attention shifting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 735–747.

Young Mun, E., Fitzgerald, H. E., Von Eye, A., Puttler, L. I., & Zucker, R. A. (2001). Temperamental characteristics as predictors of externalizing and internalizing child behavior problems in the contexts of high and low parental psychopathology. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22, 393–415.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part a National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) training grant supporting the work of Miriam Forbes (T320A037183). NIDA had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in writing; nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children is conducted in partnership between the Department of Social Services, the Australian Institute of Family Studies, and the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Role of Funding Source

This research was supported in part a National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) training grant supporting the work of Miriam Forbes (T320A037183). NIDA had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in writing; nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Forbes, M.K., Rapee, R.M., Camberis, AL. et al. Unique Associations between Childhood Temperament Characteristics and Subsequent Psychopathology Symptom Trajectories from Childhood to Early Adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 45, 1221–1233 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0236-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0236-7