Abstract

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) can create sophisticated textual and multimodal content readily available to students. Writing intensive courses and disciplines that use writing as a major form of assessment are significantly impacted by advancements in generative AI, as the technology has the potential to revolutionize how students write and how they perceive writing as a fundamental literacy skill. However, educators are still at the beginning stage of understanding students’ integration of generative AI in their actual writing process. This study addresses the urgent need to uncover how students engage with ChatGPT throughout different components of their writing processes and their perceptions of the opportunities and challenges of generative AI. Adopting a phenomenological research design, the study explored the writing practices of six students, including both native and nonnative English speakers, in a first-year writing class at a higher education institution in the US. Thematic analysis of students’ written products, self-reflections, and interviews suggests that students utilized ChatGPT for brainstorming and organizing ideas as well as assisting with both global (e.g., argument, structure, coherence) and local issues of writing (e.g., syntax, diction, grammar), while they also had various ethical and practical concerns about the use of ChatGPT. The study brought to front two dilemmas encountered by students in their generative AI-assisted writing: (1) the challenging balance between incorporating AI to enhance writing and maintaining their authentic voice, and (2) the dilemma of weighing the potential loss of learning experiences against the emergence of new learning opportunities accompanying AI integration. These dilemmas highlight the need to rethink learning in an increasingly AI-mediated educational context, emphasizing the importance of fostering students’ critical AI literacy to promote their authorial voice and learning in AI-human collaboration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The rapid development of large language models such as ChatGPT and AI-powered writing tools has led to a blend of apprehension, anxiety, curiosity, and optimism among educators (Warner, 2022). While some are optimistic about the opportunities that generative AI brings to classrooms, various concerns arise especially in terms of academic dishonesty and the biases inherent in these AI tools (Glaser, 2023). Writing classes and disciplines that use writing as a major form of assessment, in particular, are significantly impacted. Generative AI has the potential to transform how students approach writing tasks and demonstrate learning through writing, thus impacting how they view writing as an essential literacy skill. Educators are concerned that when used improperly, the increasingly AI-mediated literacy practices may AI-nize students’ writing and thinking.

Despite the heated discussion among educators, there remains a notable gap in empirical research on the application of generative AI in writing classrooms (Yan, 2023) and minimal research that systematically examines students’ integration of AI in their writing processes (Barrot, 2023a). Writing–an activity often undertaken outside the classroom walls–eludes comprehensive observation by educators, leaving a gap in instructors’ understandings of students’ AI-assisted writing practices. Furthermore, the widespread institutional skepticism and critical discourse surrounding the use of generative AI in academic writing may deter students from openly sharing their genuine opinions of and experiences with AI-assisted writing. These situations can cause disconnect between students’ real-life practices and instructors’ understandings. Thus, there is a critical need for in-depth investigation into students’ decision-making processes involved in their generative AI-assisted writing.

To fill this research gap, the current study explores nuanced ways students utilize ChatGPT, a generative AI tool, to support their academic writing in a college-level composition class in the US. Specifically, the study adopts a phenomenological design to examine how college students use ChatGPT throughout the various components of their writing processes such as brainstorming, revising, and editing. Using sense-making theory as the theoretical lens, the study also analyzes students’ perceived benefits, challenges, and considerations regarding AI-assisted academic writing. As writing is also a linguistic activity, this study includes both native and non-native speaking writers, since they may have distinct needs and perspectives on the support and challenges AI provides for writing.

2 Literature Review

2.1 AI-Assisted Writing

Researchers have long been studying the utilization of AI technologies to support writing and language learning (Schulze, 2008). Three major technological innovations have revolutionized writing: (1) word processors, which represented the first major shift from manual to digital writing, replacing traditional typewriters and manual editing processes; (2) the Internet, which introduced web-based platforms, largely promoting the communication and interactivity of writing; and (3) natural language processing (NLP) and artificial intelligence, bringing about tools capable of real-time feedback and content and thinking assistance (Kruse et al., 2023). These technologies have changed writing from a traditionally manual and individual activity into a highly digital nature, radically transforming the writing processes, writers’ behaviors, and the teaching of writing. This evolution reflects a broader need towards a technologically sophisticated approach to writing instruction.

AI technologies have been used in writing instruction in various ways, ranging from assisting in the writing process to evaluating written works. One prominent application is automatic written evaluation (AWE), which comprises two main elements: a scoring engine producing automatic scores and a feedback engine delivering automated written corrective feedback (AWCF) (Koltovskaia, 2020). Adopting NLP to analyze language features, diagnose errors, and evaluate essays, AWE was first implemented in high-stakes testing and later adopted in writing classrooms (Link et al., 2022). Scholars have reported contrasting findings regarding the impact of AWE on student writing (Koltovskaia, 2020). Barrot (2023b) finds that tools offering AWCF, such as Grammarly, improves students’ overall writing accuracy and metalinguistic awareness, as AWCF allows students to engage with self-directed learning about writing via personalized feedback. Thus the system can contribute to classroom instruction by reducing the burden on teachers and aiding students in writing, revision, and self-learning (Almusharraf & Alotaibi, 2023). However, scholars have also raised concerns regarding its accuracy and its potential misrepresentation of the social nature of writing (Shi & Aryadoust, 2023). Another AI application that has been used to assist student writing is intelligent tutoring system (ITS). Research shows that ITS could enhance students’ vocabulary and grammar development, offer immediate sentence- and paragraph-level suggestions, and provide insights into students’ writing behaviors (Jeon, 2021; Pandarova et al., 2019). Scholars also investigate chatbots as writing partners for scaffolding students’ argumentative writing (Guo et al., 2022; Lin & Chang, 2020) and incorporating Google’s neural machine translation system in second language (L2) writing (Cancino & Panes, 2021; Tsai, 2019).

Research suggests that adopting AI in literacy and language education has advantages such as supporting personalized learning experiences, providing differentiated and immediate feedback (Huang et al., 2022; Bahari, 2021), and reducing students’ cognitive barriers (Gayed et al., 2022). Researchers also note challenges such as the varied level of technological readiness among teachers and students as well as concerns regarding accuracy, biases, accountability, transparency, and ethics (e.g., Kohnke et al., 2023; Memarian & Doleck, 2023; Ranalli, 2021).

2.2 Integrating Generative AI into Writing

With sophisticated and multilingual language generation capabilities, the latest advancements of generative AI and large language models, such as ChatGPT, unlock new possibilities and challenges. Scholars have discussed how generative AI can be used in writing classrooms. Tseng and Warschauer (2023) point out that ChatGPT and AI-writing tools may rob language learners of essential learning experiences; however, if banning them, students will also lose essential opportunities to learn how to use AI in supporting their learning and their future work. They suggest that educators should not try to “beat” but rather “join” and “partner with” AI (p. 1). Barrot (2023a) and Su et al. (2023) both review ChatGPT’s benefits and challenges for writing, pointing out that ChatGPT can offer a wide range of context-specific writing assistance such as idea generation, outlining, content improvement, organization, editing, proofreading, and post-writing reflection. Similar to Tseng and Warschauer (2023), Barrot (2023a) is also concerned about students’ learning loss due to their use of generative AI in writing and their over-reliance on AI. Moreover, Su et al. (2023) specifically raise concerns about the issues of authorship and plagiarism, as well as ChatGPT’s shortcomings in logical reasoning and information accuracy.

Among the existing empirical research, studies have explored the quality of generative AI’s feedback on student essays in comparison to human feedback. Steiss et al. (2024) analyzed 400 feedback instances—half generated by human raters and half by ChatGPT—on the same essays. The findings showed that human raters provided higher-quality feedback in terms of clarity, accuracy, supportive tone, and emphasis on critical aspects for improvement. In contrast, AI feedback shone in delivering criteria-based evaluations. The study generated important implications for balancing the strengths and limitations of ChatGPT and human feedback for assessing student essays. Other research also examined the role of generative AI tools in L1 multimodal writing instruction (Tan et al., 2024), L1 student writers’ perceptions of ChatGPT as writing partner and AI ethics in college composition classes (Vetter et al., 2024), and the collaborative experience of writing instructors and students in integrating generative AI into writing (Bedington et al., 2024).

Specifically with regard to classroom-based research in L2 writing, Yan (2023) examined the use of ChatGPT through the design of a one-week L2 writing practicum at a Chinese university. Analyzing eight students’ classroom behaviors, learning logs, and interviews, the study showed that the use of generative AI helped L2 learners write with fewer grammatical errors and more lexical diversity. The study also found that the students’ biggest concerns were the threat to academic honesty and educational equity. This study is a pioneer in exploring students’ strategies and engagement with ChatGPT in writing; however, it was only conducted through a one-week practicum which did not involve authentic writing assignment tasks. Furthermore, students’ use of ChatGPT was limited to editing AI-generated texts instead of incorporating AI in a wider range of writing activities such as pre-writing and revising human generated texts. In another study by Han et al. (2023), the authors designed a platform that integrated ChatGPT to support L2 writers in improving writing quality in South Korea. Analyzing 213 students’ interaction data with the platform, survey results, as well as a focus group interview with six students and one instructor, the study found that the students generally held positive experiences with ChatGPT in supporting their academic writing. Although the study undertook a more extensive investigation involving a larger poll of participants with authentic writing assignments, it only explored generative AI’s role as a revision tool without examining its use across various stages of writing. Furthermore, participants in this study were tasked with engaging with a ChatGPT embedded platform of predefined prompts designed by the researchers. Consequently, how students interact with ChatGPT in natural settings remains largely unknown for researchers and educators.

2.3 Writing Process

Since the early 1980s until now, scholars have proposed various writing process models (e.g., Abdel Latif, 2021; Flower & Hayes, 1981; Hayes, 2012; Kellogg, 1996), yet they are still trying to form a complete understanding of composing processes. Despite the distinct specific aspects that different models highlight in the writing process, they all negate writing as a linear, sequential process of simply a text generation labor, but emphasize the non-linear and recursive nature of the writing process. Abdel Latif (2021) noted that various components of writing process such as ideational planning, searching for content, and revising interact with each other, and that both novice and experienced writers employ all of the components but with varying degrees and strategies. For instance, skilled writers refine and revise their ideas during writing, whereas novice writers mostly engage in sentence level changes such as fixing grammatical and lexical issues (e.g., Khuder & Harwood, 2015). For L2 students, writing can be very complex and cognitively daunting (Mohsen, 2021) due to reasons including but not limited to linguistic barriers (Johnson, 2017). Furthermore, writing is more than a cognitive process, it is also a social, cultural, and situated activity. For instance, the concept of plagiarism may carry different meanings and consequences across different cultural contexts. Thus, writing should be investigated in consideration of its dynamic interplay with institutional, cultural, and technological factors (Atkinson, 2003).

Considering the intricate nature of writing as a cognitive and social activity, it is thus important to investigate how generative AI may impact the different components of students’ writing processes. However, there is still a substantial gap in knowledge and research about students’ real-world integration of AI into their writing workflows, their decision-making processes, and the rationale behind their decision making while they interact with generative AI and utilize the technology in their writing in formal educational settings. While previous studies shed light on the impacts of generative AI on English writing, empirical classroom-based research remains limited. To further understand how students, both L1 and L2 writers, engage with generative AI in real-life classroom contexts, with authentic writing tasks, and throughout their various processes of writing, the current study thus undertook a naturalistic, exploratory direction that focused on how college students utilized ChatGPT in a first-year writing class in the US. Understanding and unpacking students’ AI-assisted writing processes could help educators better adjust their pedagogy in the face of the growing AI influences. The following research questions guided the present study:

-

1.

How do students utilize ChatGPT in their writing processes?

-

2.

How do student writers perceive the benefits of integrating ChatGPT into their writing?

-

3.

What concerns and limitations do students experience when using ChatGPT to assist with their writing?

-

4.

What considerations do students identify as important when engaging in generative AI-assisted writing?

3 Theoretical Framework

This study adopts sensemaking theory as its theoretical lens. Sensemaking has been conceptualized as the process through which individuals make meaning from ambiguous and puzzling situations that happen in their experience (Golob, 2018). Some scholars view sensemaking as a cognitive process of managing and processing information. This perspective focuses on the cognitive strategies employed in connecting and utilizing information to achieve the purpose of explaining the world (Klein et al., 2006). Alternatively, a socio-cultural orientation towards sensemaking regard it as construction of collective identity through an individual’s ongoing interactions with the educational context (Weick, 2005). Poquet (2024) integrates these two theoretical orientations, proposing that sensemaking encompasses both the individual and the collective, drawing attention to how learners explain the cognitive aspects of their learning as well as the social and cultural factors shape their learning experiences.

According to Poquet (2024), there are three components of the sensemaking process: (1) An individual’s understanding of the activity, available tools, and the situation is the antecedent of sensemaking. (2) Noticing and perceiving constitute the process of sensemaking per se. Noticing involves the identification of salient features of the tool(s) for the activity, while perceiving goes beyond noticing through making sense of the observed, taking into account contextual factors such as learner characteristics and the type of activity undertaken. Perceiving leads to the formulation of meaning and potential implications of what is noticed, playing a critical role in decision-making and action. (3) Outcomes of sensemaking may range from perceived affordances of tools for the activity to casual explanations for the observed phenomena. As defined by Poquet (2024), sensemaking involves learners crafting explanations for unclear situations through dynamically connecting information within the context of a specific activity. Essentially, sensemaking is both an intentional and intuitive process shaped by how learners understand their environment and their role within it.

Because sensemaking theories aim to examine people’s meaning-making, acting, and experience in “unknown,” “less deliberate,” and “more intuitive” situations (Poquet, 2024, p. 5), it well aligns with the purpose of this study which is to form an emergent understanding of a less known situation given the relatively new phenomenon of generative AI-assisted writing practices among college students. Adopting a sensemaking lens helps to understand how students make sense of generative AI, how they perceive its affordances, what strategies they develop to use it to assist with their writing, what puzzling experiences they may have, and how they make decisions in those puzzling situations. The dual focus of the cognitive and the social is critical when examining how students engage with and perceive the AI technology and how they negotiate these perceptions and experiences within the learning communities of higher education. Sensemaking theory can also capture the range of individual experiences and shared interpretations among them, elucidating how they deal with uncertainty and make judgments generative AI usage.

4 Research Design

This qualitative study adopted a phenomenological research design, which focuses on understanding and interpreting a particular aspect of shared human experience (Moran, 2002; Smith, 1996). Phenomenology seeks to form a close and clear account of people’s perceptions and lived experiences as opposed to delivering a positivist conclusion of human encounters, as “pure experience is never accessible” (Smith et al., 2009, p. 33). In the present study, as there is limited understanding of students’ engagement with ChatGPT in their writing process, a phenomenological lens could help capture participants’ own sense making of their AI-assisted writing experiences.

4.1 Context and Participants

The study took place in spring 2023 at a higher education institution in the US. I chose to focus on first-year writing as the study setting, as it is a required course in most colleges and universities, thus a typical writing and learning context for most college students. First-year writing serves as the foundation for cultivating academic writing skills, with the aim of developing students’ essential literacy and writing proficiency needed for their undergraduate learning experiences. The 14-week course focused on English academic reading, writing, and critical thinking and consisted of three major units.

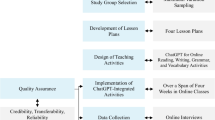

This study focused on the last unit, which was about argumentative writing, a common type of academic essay writing (American Psychological Association, 2020). The final essay asked students to form an argumentative response to a research question of their own choice. The unit, lasting for three weeks, was structured as follows (see Fig. 1): During the first week, the instructor spent two classes, each for 75 min, introducing ChatGPT (GPT 3.5) as a large language model and inviting students to explore ChatGPT as a tool for writing. The instructor carefully chose and assigned five readings that allowed the students to grasp the ongoing academic and public debates and concerns regarding the use of ChatGPT in writing and educational settings. During the class sessions, students participated in various activities exploring the functionalities of ChatGPT, discussed ethics and academic integrity, and critiqued AI-generated writing. As part of the discussions on ethics, the instructor explicitly addressed academic integrity issues drawing upon both the writing program’s guidelines and the institution’s academic integrity policies to ensure that the students were aware of and committed to ethical use of generative AI in the writing class. During the second week, students learned various strategies for integrating sources in academic writing and practiced ways of using sources to build arguments. During the last week, students spent time peer reviewing each other’s work and met with the instructor individually to improve their drafts.

The final essay allowed but did not mandate students to use ChatGPT. For those who used ChatGPT and AI writing tools, disclosure and transparency about how AI was used were required as part of the submission to the assignment. The instructor left using AI in their final essay as an open option to the students themselves, ensuring that students could pursue the option that works best for their individual needs. Thus the unit provided various opportunities and flexibility for planning, researching, drafting, reviewing, and editing with ChatGPT throughout students’ writing process.

There were 11 students, all freshmen, enrolled in the class. All but one reported using ChatGPT in their writing. Six students were recruited based on their willingness to participate and the diversity of their first language to ensure a balanced coverage. Table 1 shows the demographic information of the students (with pseudonyms).

4.2 Data Collection

Aligned with an interpretive phenomenological design that focuses on exploring participants’ lived experiences and how they construct meaning of their own experiences (Smith & Shinebourne, 2012), I collected three major types of data in order to uncover the students’ writing processes involving ChatGPT and their perceptions. First, I collected students’ written products and artifacts such as in-class writing, screenshots of students’ conversations with ChatGPT, informal short writing assignments, and the formal writing assignments for the final argumentative essay. Second, I collected students’ written self-reflections about their use of ChatGPT in writing. Finally, the participants were interviewed for around 30–40 min, and all interviews were audio-recorded. These semi-structured interviews were developed around students’ former experiences with ChatGPT, their views of the tool, and the ways they utilized ChatGPT for their writing assignments in this class.

Students’ conversational screenshots with ChatGPT and their in-class and outside class writing drafts could demonstrate their interactions with AI as well as the changes they made upon contemplating the responses from the chatbot. The interviews and students’ self-reflections could further shed light on their perceptions and decision-making. Multiple sources of data helped to understand students’ behaviors, perceptions, and engagement with AI during different stages of writing. Triangulation of the data also helped me to understand students’ rationale for and practices of integrating, discounting, and reflecting on the chatbot’s output into their writing.

It is important to note that a phenomenological qualitative research design like this aims to provide in-depth understanding and insights into participants’ experiences. The context of the study—a first year writing class—and the specific type of assignment investigated are both common scenarios in college classrooms, thereby enhancing the study’s relevance despite its limited sample size and scale. Furthermore, the incorporation of data collected from multiple and diverse sources for triangulation adds to insights into participants’ experiences, which helps strengthen the credibility of the study.

4.3 Data Analysis

Thematic analysis (Creswell, 2017) was used to analyze the written drafts and transcriptions of interview data as it is commonly used in qualitative studies to identify patterns across various types of data (Lapadat, 2012). While transcribing all the interview data verbatim into written scripts, I took notes with the research questions in mind. Then I organized and read through the various types of written data to get familiar with and form a holistic impression of participants’ perceptions and experiences of AI-assisted writing. The coding, conducted on Nvivo, a qualitative data analysis software, followed an inductive and iterative process. During the first cycle of coding, I reviewed the data line-by-line and applied in vivo coding to generate initial, descriptive codes using participants’ voices (Saldaña, 2016). For the second cycle, I identified patterns across the in vivo codes and synthesized them into 20 pattern codes (Saldaña, 2016). During the third cycle, I clustered and grouped the pattern codes into four emerging themes. To finalize and refine the themes, I double checked themes, codes, and the supporting data guided by the research questions. Table 2 shows the themes and pattern codes. To ensure the trustworthiness of the qualitative analysis, I also conducted a peer debriefing (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) on the codebook with an experienced qualitative researcher. Furthermore, member check was also conducted with each participant via email to minimize the possible misinterpretations of their perceptions and experiences.

5 Findings

5.1 How Do Students Utilize ChatGPT in Their Writing Processes?

The students reported using ChatGPT throughout different components of writing their argumentative essays including (1) brainstorming, (2) outlining, (3) revising, and (4) editing.

In terms of brainstorming, the students acknowledged the value of ChatGPT in helping them get initial ideas and inspirations prior to the research phase for their essays. For instance, Lydia was interested in writing about the cause of the low fertility rate in South Korea but she “had trouble thinking of any focus areas” (Lydia, Reflection). In order to narrow down the topic and find a good focus, she used ChatGPT for exploring possible directions she could pursue. As she noted:

It immediately gave me suggestions to approach the cause from demographic changes, economic factors, traditional gender roles, governmental policies, and cultural attitudes with detailed explanations beside each suggestion. So, I went on to pick economic reasons, which I think were the most accessible to write about. (Lydia, Reflection)

ChatGPT’s feedback facilitated a smoother decision-making process for Lydia regarding the specific topic to further investigate. Another student Kevin mentioned that running his initial research idea into ChatGPT was helpful because ChatGPT gave him “some relevant ideas that hadn’t crossed his mind when thinking about the topic” (Kevin, Written Assignment).

Considering ChatGPT’s suggestions did not mean that the students just took them for granted and incorporated them unquestioningly. For instance, Nora was interested in writing about the impact of AI on human lives. Upon putting her initial research question into ChatGPT, she found the feedback helpful and decided to do more research on the aspects highlighted by ChatGPT (see Fig. 2).

Students also reported using ChatGPT for outlining. Emma used ChatGPT extensively to help organize her outline and shared her procedure as follows:

I wrote my own outline first consisting of my own ideas and then put it into ChatGPT. I asked ChatGPT to make the outline flow better. I was surprised with the results it gave me. It made the ideas more concise and connected better off of each other...I tried it a few times, and every time it gave me a different version of the outline that I could potentially use. I ultimately compared the information from my sources and chose an outline I thought best suited my essay and my essay question. (Emma, Reflection)

Emma’s approach revolved around utilizing ChatGPT to unearth linkages among her various initial yet disorganized ideas she already had. By experimenting with diverse ways to build coherence and connection among her thoughts with the aid of AI, she shortcut the mental task of structuring her ideas from scratch.

Using ChatGPT for refining the flow of ideas was also a strategy adopted by other students, but not always during the outlining stage. For instance, after completing her first draft, Lydia “copied and pasted her entire essay into the chatbox and asked for suggestions on how to improve the structure and argument” (Lydia, Reflection). Lydia underlined that her revision process with ChatGPT was iterative, as she put her revised version back into the chatbot and went through another round of feedback and subsequent revision. Additional applications reported by students also encompassed employing ChatGPT to reduce redundancy and enhance conciseness of content (Emma) as well as to refine topic sentences for accurately summarizing the main ideas of body paragraphs (Kevin).

Apart from utilizing ChatGPT to assist with global level issues such as structure, argument, and coherence, the students also harnessed the AI tool for sentence-level issues. They unanimously agreed that ChatGPT was a valuable tool for language editing. Alex, a L1 student, commented that ChatGPT could edit essays “exceptionally well.” Alex not only used the AI tool to help improve the syntax of his writing such as “run-on sentences” but also consulted it as his dictionary for “providing academic diction” (Alex, Interview). The L2 participants particularly acknowledged ChatGPT as beneficial for enhancing the accuracy of their writing. Lydia shared that upon completing a paragraph of her essay, she would put it into ChatGPT and ask it to “revise the wording and grammar only” so she could refine her language and keep the content original (Lydia, Reflection). Another L2 student Nora noted that “when I struggle with expressing my thoughts accurately in English words, ChatGPT can help me express those ideas in a more powerful and accurate way. It removes communication barriers” (Nora, Written Assignment).

5.2 How Do Student Writers Perceive the Benefits of Integrating ChatGPT into Their Writing?

Utilizing ChatGPT in their various writing process components, the students reported that ChatGPT had the following benefits: (1) accelerating their writing process, (2) easing their cognitive load, (3) fostering new learning opportunities, (4) getting immediate feedback, and (5) promoting positive feelings about writing.

Students stated that using ChatGPT could “speed up the process of writing” (Alex, Interview) as exemplified by the following quotes: “ChatGPT really helped me to explore the essay topics that I’m interested in within a very short amount of time and identify what can be written about” (Nora, Interview); “I discovered after using it for my final essay that ChatGPT can greatly improve the efficiency of my writing” (Alex, Reflection). For L2 writers, it significantly saved the time they typically spent on editing, as mentioned by Lydia:

As an international student who is not a native English speaker, writing college essays would take me double the amount of time compared to those who write essays in their first language. Oftentimes, the biggest time I spent was on editing the grammar and trying to make my language readable and understandable. (Lydia, Reflection)

The benefits of saving the time and energy on language concerns, grammar, wording, and the organization of ideas and messy drafts, furthermore, reduced the cognitive burden among the student writers, both L1 and L2. For instance, knowing ChatGPT’s editing power, Alex felt that he was able to “focus more on the subject of the writing rather than the language itself” and “spew out thoughts freely” when drafting the essay (Alex, Interview). Likewise, the L2 students noted that ChatGPT allowed them to delay their concerns about the linguistic forms of ideas and alleviate the demanding cognitive load associated with L2 writing. As claimed by Lydia, “It freed my thoughts so that I could spend more time revising the content, but not worry about how to express my ideas for the essay” (Lydia, Interview).

The students conveyed that incorporating ChatGPT in different components of writing also fostered new learning opportunities for them to improve writing. Nora shared that “ChatGPT not only made my language more fluent and comprehensible, but it also helped me to learn new ways of expression in English” (Nora, Interview). Su remarked that although ChatGPT’s feedback was generic, it promoted her to do further research about her topic and learn more writing strategies (Su, Written Assignment).

Students particularly highlighted the “instant and personalized feedback” (Kevin, Reflection) provided by ChatGPT as a strong impetus and benefit. For instance, as a frequent visitor of the school’s writing center, Lydia mentioned she typically scheduled two to three appointments with a writing tutor for each major writing assignment she had worked. With ChatGPT, she could obtain feedback anytime: “Now I don’t have to physically go to the writing center at 11 pm, waiting for the previous visitor to finish their session” (Lydia, Interview). She used “my walking AI tutor” to describe the role of AI in her writing.

Ultimately, the students mentioned that these cognitive and practical benefits of ChatGPT not only improved their efficiency of writing, but also promoted positive feelings about writing. They used words such as “more relieved” (Emma), “sense of accomplishment” (Lydia), and “less anxious” (Nora) to describe the AI-assisted writing process. Although the students expressed different needs and utilization of ChatGPT, they all conveyed that they would like to continue using it in the future.

5.3 What Concerns and Limitations Do Students Experience When Using ChatGPT to Assist with Their Writing?

Despite the benefits and usefulness of ChatGPT for assisting with students’ writing, they also expressed many reservations and limitations regarding the AI tool. The first concern was about the false information it produced and its potential to mislead people. The students commented that ChatGPT tended to “make up information” (Emma), “make assumptions and guesses” (Su), and generate “inaccurate information” (Nora), “wrong information” (Alex), and “nonsense” (Lydia). Furthermore, the students pointed out that ChatGPT was inadequate in addressing high-level questions requiring critical thinking, as Su explained: “When I was consulting with ChatGPT, I learned that it has a very limited understanding of the topic I was talking about” (Su, Reflection). Other students also pointed out that the responses they got from ChatGPT could be “very generalized” (Kevin) and lacked “depth and complexity” (Nora).

The next shortcoming of ChatGPT, as noted by the students, is the lack of creativity and originality. Su highlighted that relying on ChatGPT’s ideas would not yield intriguing essays, as even though ChatGPT’s responses may “appear to make sense,” they usually came across as “cliched and superficial.” Su understood that it was because ChatGPT and large language models “work based on the patterns and data they have been trained on and cannot think outside of this” (Su, Reflection). Therefore, it is “not effective in generating new ideas” for an essay (Alex, Interview).

The algorithm unavoidably led to another limitation as observed by the students, which is the lack of reliable evidence and support for the content generated by ChatGPT. Su acknowledged that ChatGPT was not a good source for writing as it was impossible for a reader to trace the original information. Apart from the lack of clarity and transparency about the sources ChatGPT draws upon, Kevin pointed out an additional drawback that ChatGPT’s ideas were “not up to date,” thus not a good source for academic writing (Kevin, Written Assignment).

5.4 What Considerations Do Students Identify as Important When Engaging in Generative AI-Assisted Writing?

Presented with these limitations of ChatGPT, the students shared some important aspects they think should be considered when incorporating AI into writing, summarized as follows: (1) balanced and moderate use of AI, (2) critical use of AI, (3) ethical considerations, (4) the need for human voice, (5) the importance of authenticity, (6) seizing AI as a learning opportunity, and (7) transparency from and conversation between teachers and students.

The students worried that over-reliance on ChatGPT would undermine their writing ability, so they should use ChatGPT to a balanced and moderate extent. The students believed that ChatGPT should be used as “guidance,” “support,” “supplement,” and “assistant” (Alex, Reflection) rather than a “substitute” or “replacement” (Su, Reflection).

Furthermore, the students emphasized the importance of critical use of AI. Emma noted that AI platforms could “decline the need to think critically” as some students might want to “take the easy route and just get the answer” (Emma, Interview). They insisted keeping a critical eye on the information AI generated as it was not reliable. To do this, students shared similar strategies which was to use ChatGPT as a departure rather than a destination for writing, thinking, and research. They underscored the importance of validation and critical thinking in this process.

Another facet to consider is the ethical use of AI. The students believed that one must be very careful when using ChatGPT as it can easily walk the line of plagiarism. They deemed acts such as using ChatGPT to generate new ideas and write entire essays unethical, as these are forms of taking credit for other people’s work based on their language and ideas (Kevin, In-Class Writing). Thus students emphasized the importance of “doing research on your own” (Emma), “making sure the ideas are my own” (Lydia), and “not using everything (i.e. sentence by sentence, word by word) provided by ChatGPT” (Su).

The students also regarded the issue of retaining human voice a pivotal consideration for AI-assisted writing. They pointed out that writing should be a means to express the writer’s identity and thoughts, but AI was not able to personalize the text to their individual style and voice. Wary of the threat posed by extensive adoption of ChatGPT to individual expressions, Lydia commented, “ChatGPT tended to use similar dictions and patterns of wording and sentence structures. If everyone uses ChatGPT, our style will become more and more alike” (Lydia, Interview). Similarly, Su pointed out that ChatGPT could make the text “sound generic and impersonal,” which is a problem “when you are trying to convey your own ideas, feelings, and perspectives” (Su, Written Assignment). To “truly present a unique perspective and make writing individualized,” one must “take full control” of their writing to deliver a powerful message (Kevin, Reflection). This process requires the discernment to dismiss advice from ChatGPT to avoid generating an impersonal, blunt style of writing that lacks the writer’s distinct character.

Students also pointed out that the involvement of ChatGPT in writing may not only jeopardize how human voice is conveyed through the ideas ChatGPT generates, but also through the language it produces, thus “ruining the authenticity of an essay” (Alex, Reflection). He questioned himself for a paradoxical use of ChatGPT. On the one hand, he utilized ChatGPT for editing and better academic diction; on the other, he was perplexed and apprehended about the tipping point where the essay would start to sound “more like ChatGPT rather than yourself.” As he explained:

ChatGPT suggested some words I never would have used, and I decided not to include them. While they may obviously sound better than my own authentic words, I just did not feel honest using them. For instance, when writing this paper, ChatGPT suggested I use “judiciously” rather than “in moderation.” I never would have used “judiciously,” and it felt unauthentic to use it. (Alex, Reflection)

The students suggested cautious, strategic, and purposeful use of ChatGPT’s editing features to ensure it amplifies rather than conflicts with their own writing style.

However, boundaries like this still appeared to the students as vague. Hence, the students called for guidelines and instructions in the classroom and open conversation between teachers and students. The students expressed their confusion over the lack of clear guidelines across their classes. As Alex commented, “It’s hard to draw lines with different ways of using ChatGPT and which one would be considered cheating or not” (Alex, Interview). The students hoped that all their instructors, instead of only writing teachers, could engage in comprehensive discussions about what specific ways of using ChatGPT would be regarded as acceptable or problematic according to their disciplinary conventions and learning purposes.

Participants also expected that school policies and instructors would not shut down AI as a resource and learning opportunity for students. Emma said, “It’s tricky as there are a lot of different opinions, but technology is the world we live in. We should go with the grain as opposed to against it” (Emma, Interview). Cautious of possible missed learning opportunities that AI might bring to thinking, Lydia commented, “I am afraid of becoming lazy…But I guess it also depends on how you use it. It gives a shortcut for people who do not want to make the effort to learn and think. But it could be useful for those who really want to learn” (Lydia, Interview). Alex noted that to prevent the loss of learning opportunity, for instance, he decided that rather than taking ChatGPT’s diction suggestion immediately, he “would use those words in the next essay,” demonstrating his effort in learning and internalizing the knowledge. In general, the students were still exploring ways to use ChatGPT in critical, authentic, and ethical ways that would promote rather than harm their learning.

6 Discussion

Adopting sensemaking theory, the study investigated how students made sense of their AI-assisted writing practices, providing insights into students’ learning process and their shared practices emerging around the AI technology. Confirming previous research (e.g., Guo et al., 2022; Holmes et al., 2019; Su et al., 2023), this study found that the students overall had positive experiences with generative AI-assisted writing, for it could accelerate their writing process, reduce their cognitive load and anxiety, and provide prompt feedback. The students integrated ChatGPT into various components of their composing process, such as searching for content, ideational planning, language editing, and revising. Although the students acknowledged the cognitive and affective benefits (e.g., Ebadi & Amini, 2022; Fryer & Carpenter, 2006) of using ChatGPT in writing, they were very cautious about adopting its ideas and suggestions at different discourse levels (i.e., essay, paragraph, and sentence levels) due to critical, ethical, and authentic concerns. This finding extends previous research which identified that students’ primary concerns were academic dishonesty and educational inequity (Yan, 2023). Despite recognizing AI’s limitations such as the lack of in-depth insights (Gao et al., 2022), originality, creativity, and reliability—qualities essential for good academic writing—the students deemed it necessary to embrace rather than abandon the tool, with the purpose of fostering one’s critical thinking and writing skills. The results suggest that students’ sensemaking of AI-assisted writing is shaped by their prior knowledge and understanding of writing as a cognitive and sociocultural activity, their exploration of AI’s functionalities and strategies for leveraging them to achieve learning goals, and their interrogation of the appropriateness and limitations of AI in the specific context of academic writing.

The study highlights two emerging dilemmas students experienced in their generative AI-assisted writing processes. The first dilemma, as Alex put it, is the choice between sounding better or sounding like me when integrating AI into the decision making process of writing, reflecting a larger issue about academic integrity, authenticity, and voice in human-AI collaboration. The participants believed that it is crucial to prevent their writing from being AI-nized, which could lead to either plagiarism or a writing style resembling AI that overshadows their own voice—the very essence of their “identity and presentation of the self in writing” (Prince & Archer, 2014, p. 40). The students’ beliefs align with a connectivism paradigm of AI in Education (AIEd) outlined by Ouyang and Jiao (2021), in which AI serves as a tool to augment human intelligence and capability (Yang et al., 2021) and learner agency is placed at the core. Reliance on AI could lead to superficial engagement with writing tasks, discouraging deeper, reflective thought processes essential for original creative expression. Furthermore, when AI suggests similar vocabulary, structures, and styles to various learners, it risks imposing a uniformity in expression that undermines the educational value of cultivating each individual’s unique and creative voice. AI may hinder students from exploring how language variation and linguistic diversity can be rich resources for meaning-making, creativity, identity formation, problem-solving (Wang et al., 2020). Such critical engagement with diverse language resources is crucial for developing students’ literacy skills in a digital age where multicultural awareness is an integral part of education (Sánchez-Martín et al., 2019). As Dixon-Román et al. (2020) noted, educators must be wary of AI’s “racializing forces,” which standardize learning processes in ways that can marginalize non-dominant forms of knowledge and communication, as well as students whose experiences and identities are either not represented or misrepresented in the system.

While the participants concurred that upholding human voice and agency entails possessing integrity and alignment not only at the ideational level but also in the linguistic expression of those ideas, the L2 writers in this study added another nuanced dimension to the impact of AI on human voice and authenticity in the context of AI-assisted writing. As the L2 students experienced, ChatGPT’s language suggestions might not pose a threat to their voice but serve as a catalyst for augmenting their voice, as AI helped overcome their language barriers and better express ideas true to themselves. In other words, generative AI afforded the L2 writers powerful language repertoires that enhanced the accuracy and efficiency of “linguistic rehearing” (Abdel Latif, 2021) or “translating” (Kellogg, 1996) component of their writing process, thus allowing L2 students to produce writing more authentic to themselves. The finding highlights how learner characteristics and individual differences play an important role in students’ sensemaking of AI-assisted writing, complicating the existing understanding of AI’s affordances for learners with diverse linguistic backgrounds and learning needs.

From earlier conceptualizations of authenticity as “ownedness” and “being one’s own” by Heidegger (1927/1962), to contemporary perceptions as the “self-congruency” of an individual, group, or symbolic identity (Ferrara, 1998, p. 70), the notion of authenticity has been evolving and becoming more pluralistic. As Rings (2017) acknowledged, authenticity extends beyond adherent to personally endorsed commitments; it requires a comprehensive consideration of one’s self-awareness and the changing social context. Scholars should further pursue what it means by authenticity and academic integrity in an increasingly AI-mediated educational context, ways to promote students’ authorial voice and agency, as well as the complicated authorship issues (Jabotinsky & Sarel, 2022) involved in AI-human collaboratively generated texts. As Eaton (2023) claims, it is time to contemplate “postplagiarism” and academic integrity in a future where “hybrid human-AI writing will become normal”.

Apart from the sounding better or sounding like me dilemma experienced by students, another paradox is whether AI caused missed learning opportunities or created new learning opportunities. As noted by the previous literature, AI-writing tools may rob students of essential learning experiences (Barrot, 2023a; Tseng & Warschauer, 2023). Adding to this concern from educators and scholars, the present study shows that the students themselves are also cognizant of the possible learning loss due to AI adoption. Furthermore, the study shows that rather than passively indulging themselves in the convenience of AI tools, a common concern among educators (Chan & Hu, 2023; Graham, 2023), the student writers attempted to seize new learning opportunities that emerged from AI technologies to promote their critical thinking and writing. This finding suggests a nuanced addition to sensemaking theory: the process of making sense of uncertainties in AI-infused literacy practices can also be uncertain, involving reconciling dilemmas and acknowledging perplexing experiences. While not always yielding clear-out outcomes or casual attributions for the observed phenomena and personal experience as suggested by Poquet (2024), noticing and perceiving the unpredictable impacts of generative AI on students’ own learning processes can, in itself, be empowering. The process fosters a sense of agency and critical engagement, suggesting that the outcomes of sensemaking in the context of AI-assisted writing can be open-ended yet profound.

This important finding leads scholars to reconsider the essence of learning in an era of generative AI. Hwang et al. (2020) and Southworth et al. (2023) argued that AI is likely to transform not only the learning environment, but also the learning process, and even what it means to learn. This perspective finds resonance in the experiences of the participants in this study. While AI may shortcut traditional ways of doing writing, it does not inherently imply a reduction in students’ cognitive, behavioral, and affective engagement with writing, learning, and thinking. AI does not necessarily make writing easier; on the contrary, a critical, ethical, and authentic approach to AI-assisted writing pushes students to think further and prioritize their own voice, originality, and creativity, leading to high quality writing. In this sense, when used properly, AI has the potential to introduce a new avenue for humanizing writing and education. As generative AI technologies are advancing rapidly, an expanding array of AI-powered writing assistance, intelligent tutoring systems, and feedback tools has the promise to cater to the diverse needs and learning styles of language learners and writers. These tools are not limited to mere textual assistance; the multimodal functionalities of generative AI can also allow writers to explore creative expressions and multimodal writing, enriching students’ literacy practices by integrating more visual, auditory, and interactive elements into the composition process (Kang & Yi, 2023; Li et al., 2024). As noted by Cao and Dede (2023), our educational model has long been centered around the product, directing our focus towards the outcomes and grades students achieve, often overlooking the learning process itself. The judgmental calls involved in students’ interactions with AI, as showcased in the nuances of participants’ AI-assisted writing process in this study, represent emerging learning opportunities that require students to draw upon a range of knowledge, skills, awareness of ethics and the self, criticality, and self-reflection to make informed decisions about AI in learning. The present study shows that such decision making process can play a pivotal role in cultivating students’ “AI literacy” (Ng et al., 2021) and promoting their responsible use of AI. Therefore, it should also be recognized as a valuable teaching opportunity that educators should not overlook.

7 Conclusion

This study explored students’ generative AI-assisted writing processes in a first-year writing class in an American college. The study found that students utilized generative AI for assisting with both global (e.g., argument, structure, coherence) and local issues of writing (e.g., syntax, diction, grammar), while they also had various ethical and practical concerns about the use of AI. Findings showed that large language models offer unique benefits for L2 writers to leverage its linguistic capabilities. The study highlights the urgency of explicit teaching of critical AI literacy and the value of (post)process-oriented writing pedagogy (e.g., Graham, 2023) in college writing classrooms so that students not only understand AI writing tools’ functions and limitations but also know how to utilize and evaluate them for specific communication and learning purposes.

However, writing instruction is still at the beginning stage of addressing this pressing need. Thus, pedagogical innovations, policy adjustments, new forms of writing assessments, and teacher education (Zhai, 2022) are needed to adapt to the potential impact of AI on desired student learning outcomes within specific writing curriculums. For instance, integrating critical digital pedagogy into writing instruction and inviting students to reflect on their relevant AI literacy practices allow writing instructors to more effectively guide students in critically engaging with AI technologies in their academic literacy development. Policy adjustments should aim to cultivate an inclusive rather than “policing” environment (Johnson, 2023) that encourages students to use AI responsibly and as a means of fostering self-learning. Furthermore, writing assessment methods should evolve to not just evaluate final learning outcomes such as the written products but also the learning journey itself such as the decision-making involved in their AI-assisted writing. This shift encourages students to appreciate learning processes and the productive struggles they encounter along the way, so that they can move beyond seeing AI as a shortcut but as assistance in their quest for learning and writing development. In this way, students can leverage the linguistic, multimodal, interactive, and adaptable affordances of generative AI tools for personalized learning. This facilitates greater student ownership of their learning, enhancing their learner competence through self-direction, self-assessment, and self-reflection when interacting with AI tools (Barrot, 2023c; Fariani et al., 2023).

Following a phenomenological research design, the present study aims to provide in-depth understanding of college students’ use of ChatGPT in their academic writing, yet it is limited due to its small sample size and duration. Therefore, the findings may not apply to other classroom contexts and to a wide range of student populations. Future research could benefit from adopting a large scale, longitudinal design to examine generative AI’s impacts on student writing and students’ long-term engagement with generative AI tools, both in formal classroom settings and in informal learning contexts. It is also worth exploring students of diverse age groups and language proficiency levels as well as writing courses of different languages, purposes, and writing genres to examine other factors that may influence students’ generative AI assisted writing. After all, the participants in this study have already developed some proficiency and skills in academic writing, but holding learner agency (Ouyang & Jiao, 2021) can be more complex and challenging for younger learners. Further research is needed to understand students with varied domain knowledge, expertise, and writing abilities (Yan, 2023) and uncover individual differences in AI-assisted writing. Additionally, the participants in this study utilized GPT 3.5 for their AI-assisted writing practices. Given the rapid advancement of AI technologies, new AI models and applications are continuously emerging. Thus, future research should investigate how various AI models and functionalities might differently influence students, taking into account the ongoing developments and innovations in AI.

Data Availability

The data are available from the author upon reasonable request.

References

Abdel Latif, M. M. A. (2021). Remodeling writers’ composing processes: Implications for writing assessment. Assessing Writing, 50, 100547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2021.100547

Almusharraf, N., & Alotaibi, H. (2023). An error-analysis study from an EFL writing context: Human and automated essay scoring approaches. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 28(3), 1015–1031. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-022-09592-z

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.).

Atkinson, D. (2003). L2 writing in the post-process era: Introduction. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1060-3743(02)00123-6

Bahari, A. (2021). Computer-mediated feedback for L2 learners: Challenges versus affordances. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(1), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12481

Barrot, J. S. (2023a). Using ChatGPT for second language writing: Pitfalls and potentials. Assessing Writing, 57, 100745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2023.100745

Barrot, J. S. (2023b). Using automated written corrective feedback in the writing classrooms: Effects on L2 writing accuracy. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 36(4), 584–607.

Barrot, J. S. (2023c). ChatGPT as a language learning tool: An emerging technology report. Technology, Knowledge and Learning. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-023-09711-4

Bedington, A., Halcomb, E. F., McKee, H. A., Sargent, T., & Smith, A. (2024). Writing with generative AI and human-machine teaming: Insights and recommendations from faculty and students. Computers and Composition, 71, 102833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2024.102833

Cancino, M., & Panes, J. (2021). The impact of google translate on L2 writing quality measures: Evidence from chilean EFL high school learners. System, 98, 102464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102464

Cao, L., & Dede, C. (2023). Navigating a world of generative AI: Suggestions for educators. The next level lab at harvard graduate school of education. President and Fellows of Harvard College: Cambridge, MA.

Chan, C., & Hu, W. (2023). Students’ voices on generative AI: Perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00411-8

Creswell, J. W. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among the five traditions. Sage.

Dixon-Román, E., Nichols, T. P., & Nyame-Mensah, A. (2020). The racializing forces of/in AI educational technologies. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(3), 236–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1667825

Eaton, S. (2023). Six tenets of postplagiarism: Writing in the age of artificial intelligence. University of Calgary. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/115882.

Ebadi, S., & Amini, A. (2022). Examining the roles of social presence and human-likeness on Iranian EFL learners’ motivation using artificial intelligence technology: A case of CSIEC chatbot. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2096638

Fariani, R. I., Junus, K., & Santoso, H. B. (2023). A systematic literature review on personalised learning in the higher education context. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 28(2), 449–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-022-09628-4

Ferrara, A. (1998). Reflective authenticity. Routledge.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition & Communication, 32(4), 365–387.

Fryer, L. K., & Carpenter, R. (2006). Bots as language learning tools. Language Learning & Technology, 10, 8–14.

Gayed, J. M., Carlon, M. K. J., Oriola, A. M., & Cross, J. S. (2022). Exploring an AI-based writing Assistant’s impact on English language learners. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3, 100055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100055

Glaser, N. (2023). Exploring the potential of ChatGPT as an educational technology: An emerging technology report. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 28(4), 1945–1952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-023-09684-4

Golob, U. (2018). Sense-making. In R. L. Heath, W. Johansen, J. Falkheimer, K. Hallahan, J. J. C. Raupp, & B. Steyn (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of strategic communication (pp. 1–9). Wiley.

Graham, S. S. (2023). Post-process but not post-writing: large language models and a future for composition pedagogy. Composition Studies, 51(1), 162–218.

Guo, K., Wang, J., & Chu, S. K. W. (2022). Using chatbots to scaffold EFL students’ argumentative writing. Assessing Writing, 54, 100666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2022.100666

Han, J., Yoo, H., Kim, Y., Myung, J., Kim, M., Lim, H., Kim, J., Lee, T., Hong, H., Ahn, S., & Oh, A. (2023). RECIPE: How to Integrate ChatGPT into EFL writing education. arXiv:2305.11583. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.11583

Hayes, J. R. (2012). Modeling and remodeling writing. Written Communication, 29(3), 369–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088312451260

Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). New York: Harper & Row (Original work published 1927).

Holmes, W., Bialik, M., & Fadel, C. (2019). Artificial intelligence in education: Promises and implications for teaching and learning. Center for Curriculum Redesign.

Huang, W., Hew, K., & Fryer, L. (2022). Chatbots for language learning—Are they really useful? A systematic review of chatbot-supported language learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(1), 237–257.

Hwang, G. J., Xie, H., Wah, B. W., & Gašević, D. (2020). Vision, challenges, roles and research issues of Artificial Intelligence in Education. Computers & Education: Artificial Intelligence, 1, Article 100001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2020.100001

Jabotinsky, H. Y., & Sarel, R. (2022). Co-authoring with an AI? Ethical dilemmas and artificial intelligence. SSRN Scholarly Paper. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4303959

Jeon, J. (2021). Chatbot-assisted dynamic assessment (CA-DA) for L2 vocabulary learning and diagnosis. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 36(7), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1987272

Johnson, M. D. (2017). Cognitive task complexity and L2 written syntactic complexity, accuracy, lexical complexity, and fluency: A research synthesis and meta-analysis. Journal of Second Language Writing, 37, 13–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2017.06.001

Johnson, G. P. (2023). Don’t act like you forgot: Approaching another literacy “crisis” by (re)considering what we know about teaching writing with and through technologies. Composition Studies, 51(1), 169–175.

Kang, J., & Yi, Y. (2023). Beyond ChatGPT: Multimodal generative AI for L2 writers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 62, 101070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2023.101070

Kellogg, R. T. (1996). A model of working memory in writing. In C. M. Levy & S. Ransdell (Eds.), The science of writing: Theories, methods, individual differences and applications (pp. 57–71). Laurence Erlbaum Associates.

Khuder, B., & Harwood, N. (2015). Writing in test and non-test situations: Process and product. Journal of Writing Research, 6(3), 233–278.

Klein, G., Moon, B., & Hoffman, R. R. (2006). Making sense of sensemaking: A macrocognitive model. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 21(5), 88–92.

Kohnke, L., Moorhouse, B. L., & Zou, D. (2023). Exploring generative artificial intelligence preparedness among university language instructors: A case study. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5, 100156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100156

Koltovskaia, S. (2020). Student engagement with automated written corrective feedback (AWCF) provided by Grammarly: A multiple case study. Assessing Writing, 44, 100450.

Kruse, O., Rapp, C., Anson, C., Benetos, K., Cotos, E., Devitt, A., & Shibani, A. (Eds.). (2023). Digital writing technologies in higher education. Springer.

Lapadat, J. C. (2012). Thematic analysis. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Weibe (Eds.), The encyclopedia of case study research (pp. 926–927). Sage.

Li, B., Wang, C., Bonk, C., & Kou, X. (2024). Exploring inventions in self-directed language learning with generative AI: Implementations and perspectives of YouTube content creators. TechTrends. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-024-00960-3

Lin, M. P. C., & Chang, D. (2020). Enhancing post-secondary writers’ writing skills with a chatbot: A mixed-method classroom study. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 23(1), 78–92.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

Link, S., Mehrzad, M., & Rahimi, M. (2022). Impact of automated writing evaluation on teacher feedback, student revision, and writing improvement. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 605–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1743323

Memarian, B., & Doleck, T. (2023). Fairness, accountability, transparency, and ethics (FATE) in artificial intelligence (AI), and higher education: A systematic review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100152

Mohsen, M. A. (2021). L1 versus L2 writing processes: What insight can we obtain from a keystroke logging program? Language Teaching Research, 4, 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211041292

Moran, D. (2002). Introduction to phenomenology. Routledge.

Ng, D., Leung, J., Chu, S., & Qiao, M. (2021). Conceptualizing AI literacy: An exploratory review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100041

Ouyang, F., & Jiao, P. (2021). Artificial intelligence in education: The three paradigms. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100020

Pandarova, I., Schmidt, T., Hartig, J., Boubekki, A., Jones, R. D., & Brefeld, U. (2019). Predicting the difficulty of exercise items for dynamic difficulty adaptation in adaptive language tutoring. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 29(3), 342–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-019-00180-4

Poquet, O. (2024). A shared lens around sensemaking in learning analytics: What activity theory, definition of a situation and affordances can offer. British Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13435

Prince, R., & Archer, A. (2014). Exploring voice in multimodal quantitative texts. Literacy & Numeracy Studies, 22(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.5130/lns.v22i1.4178

Ranalli, J. (2021). L2 student engagement with automated feedback on writing: Potential for learning and issues of trust. Journal of Second Language Writing, 52, 100816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2021.100816

Rings, M. (2017). Authenticity, self-fulfillment, and self-acknowledgment. The Journal of Value Inquiry, 51(3), 475–489.

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage.

Sanchez-Martin, C., Hirsu, L., Gonzales, L., & Alvarez, S. P. (2019). Pedagogies of digital composing through a translingual approach. Computers and Composition, 52, 142–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2019.02.007

Schulze, M. (2008). AI in CALL: Artificially inflated or almost imminent? CALICO Journal, 25(3), 510–527. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v25i3.510-527

Shi, H., & Aryadoust, V. (2023). A systematic review of automated writing evaluation systems. Education and Information Technologies, 28(1), 771–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11200-7

Smith, J. A. (1996). Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: Using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychology and Health, 11(2), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449608400256

Smith, J. A., Flower, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Sage.

Smith, J. A., & Shinebourne, P. (2012). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher. (Eds.), Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 73–82). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-005.

Southworth, J., Migliaccio, K., Glover, J., Reed, D., McCarty, C., Brendemuhl, J., & Thomas, A. (2023). Developing a model for AI Across the curriculum: Transforming the higher education landscape via innovation in AI literacy. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 4, 100127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100127

Steiss, J., Tate, T. P., Graham, S., Cruz, J., Hebert, M., Wang, J., Moon, Y., Tseng, W., Warschauer, M., & Olson, C. (2024). Comparing the quality of human and ChatGPT feedback on students’ writing. Learning and Instruction. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2024.101894

Su, Y., Lin, Y., & Lai, C. (2023). Collaborating with ChatGPT in argumentative writing classrooms. Assessing Writing, 57, 100752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2023.100752

Tan, X., Xu, W., & Wang, C. (2024). Purposeful remixing with generative AI: Constructing designer voice in multimodal composing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.19095.

Tsai, S. C. (2019). Using google translate in EFL drafts: A preliminary investigation. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 32(5–6), 510–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1527361

Tseng, W., & Warschauer, M. (2023). AI-writing tools in education: If you can’t beat them, join them. Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning, 3(2), 258–262. https://doi.org/10.1515/jccall-2023-0008

Vetter, M. A., Lucia, B., Jiang, J., & Othman, M. (2024). Towards a framework for local interrogation of AI ethics: A case study on text generators, academic integrity, and composing with ChatGPT. Computers and Composition, 71, 102831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2024.102831

Wang, C., Samuelson, B., & Silvester, K. (2020). Zhai nan, mai meng and filial piety: The translingual creativity of Chinese university students in an academic writing course. Journal of Global Literacies, Technologies, and Emerging Pedagogies, 6(2), 1120–1143.

Warner, B. (2022). AI for Language Learning: ChatGPT and the Future of ELT. TESOL. http://blog.tesol.org/ai-for-language-learning-chatgpt-and-the-future-of-elt/?utm_content=buffer7d9a4&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkedin.com&utm_campaign=buffer.

Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Obstfeld, D. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science, 16(4), 409–421.

Yan, D. (2023). Impact of ChatGPT on learners in a L2 writing practicum: An exploratory investigation. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11742-4

Yang, S. J., Ogata, H., Matsui, T., & Chen, N. S. (2021). Human-centered artificial intelligence in education: Seeing the invisible through the visible. Computers & Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, Article 100008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100008

Zhai, X. (2022). ChatGPT user experience: Implications for education. SSRN Scholarly Paper. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4312418.

Funding

The author acknowledges that the research did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author confirms that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study is conducted with permission from and following the guidelines of the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C. Exploring Students’ Generative AI-Assisted Writing Processes: Perceptions and Experiences from Native and Nonnative English Speakers. Tech Know Learn (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-024-09744-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-024-09744-3