Abstract

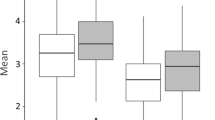

This paper explores the relationship between the student-supervisor relationship (SSR) and postgraduate students’ subjective well-being. Based on a longitudinal survey of Beijing college students, the present study suggests that in China, the SSR is a supervisor-centred, top-down hierarchical relationship. The reciprocity level of the SSR is positively related to the students’ subjective well-being. The trust level of the SSR also has a positive relationship with students’ subjective well-being; improving the trust level may also mitigate the possible negative implications of the low level of reciprocity in the relationship. The present study further reveals that it is more difficult for first-generation students to establish sound SSR than non-first-generation students. Additionally, a good SSR is more important for first-generation students’ positive well-being. The findings provide implications for educational practices on how to improve postgraduate students’ subjective well-being by improving the SSR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the survey of Woolston and Meara (2019), compared with the 72% satisfaction rate in other regions, only 55% of Chinese Ph.D. candidates were at least partially satisfied with campus life.

When carrying out research using a cross-sectional database, one key threat to valid estimation is the sample selection problem. The estimated relationship between SSR and students’ subject well-being may partly stem from some endogenous relationships, such as the relationship between students’ academic conditions in undergraduate programmes and the SSR in graduate programmes and the relationship between students’ academic conditions in undergraduate programmes and their subjective well-being in graduate programmes; then, the estimated results may be inaccurate. Compared with that, when carrying out research using longitudinal database, such sample selection problems can be solved, to some extent, through controlling students’ academic and psychological conditions in undergraduate programmes.

We measured the trust level of the SSR from the interaction perspective based on the comprehensive consideration of the accuracy of theory and testability of concepts and availability of BCSPS data. In particular, one of the important functions of trust in interactions is to decrease conflict and to increase intimacy (Cui et al. 2015; Rousseau et al. 1998). Another important function of trust in interactions is to recognize each other’s professional competence (Meyerson et al. 1996), especially in a collectivistic culture (China), where the subordinates’ approval of their superiors’ competence is highly important for trust interactions (Cui et al. 2015). Thus, we operationalize the trust level of the SSR into students’ evaluation on the two such items.

Due to limited space, estimated results are listed in the Appendix (see Appendix Table 11); here we describe the estimated results in words.

Due to space limitations, the detailed coefficients for the variable of “first-generation” are not reported in Table 3. Here we only describe the estimated results in word.

Nearest-neighbour matching is advantageous to the point that all the treatment group individuals (first-generation students in this paper) can successfully find their match objects and information on the treatment group can be fully utilized.

References

Aikens, M. L., Sadselia, S., Watkins, K., Evans, M., Eby, L. T., & Dolan, E. L. (2016). A social capital perspective on the mentoring of undergraduate life science researchers: an empirical study of undergraduate-postgraduate-faculty triads. CBE Life Sciences Education, 15(2), 1-15.

Bernier, A., Larose, S., & Soucy, N. (2009). Academic mentoring in college: the interactive role of student’s and mentor’s interpersonal dispositions. Research in Higher Education, 46(1), 29–51.

Bordogna, C. M. (2019). The effects of boundary spanning on the development of social capital between faculty members operating transnational higher education partnerships. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 217–229.

Bourdieu, P. (2006). The Forms of Capital. In H. Lauder, J. P. Brown, A. Dillabough, & A. H. Halsey (Eds.), Education, globalisation and social change (pp. 105–118). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, T. A., & Campbell, D. E. (1997). Faculty/student mentor program: effects on academic performance and retention. Research in Higher Education, 38(6), 727–742.

Chiang, K. (2003). Learning experiences of doctoral students in UK universities. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 23(1), 4–32.

Cotten, S. R., & Wilson, B. (2006). Student–faculty interactions: dynamics and determinants. Higher Education, 51(4), 487–519.

Crisp, G., & Cruz, I. (2009). Mentoring college students: a critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007. Research in Higher Education, 50(6), 525–545.

Cui, V., Vertinsky, I., Robinson, S., Branzei, O. (2015). Trust in the workplace: the role of social interaction diversity in the community and in the workplace. Business & Society, 57(2), 378–412.

de Kleijn, R. A. M., Mainhard, M. T., Meijer, P. C., Pilot, A., & Brekelmans, M. (2012). Master’s thesis supervision: relations between perceptions of the supervisor-student relationship, final grade, perceived supervisor contribution to learning and student satisfaction. Studies in Higher Education, 37(8), 925–939.

Delamont, S., Parry, O., & Atkinson, P. (1998). Creating a delicate balance: the doctoral supervisor’s dilemmas. Teaching in Higher Education, 3, 157–172.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75.

Eagan, M. K., Hurtado, S., Chang, M. J., Garcia, G. A., Herrera, F. A., & Garibay, J. C. (2013). Making a difference in science education. American Educational Research Journal, 50(4), 683–713.

Egan, R., Stockley, D., Brouwer, B., Tripp, D., Stechyson, N. (2009). Relationships between area of academic concentration, supervisory style, student needs and best practices. Studies in Higher Education, 34(3), 337–345.

Fazio, T. Academic apprenticeship: Developing novice academic teaching and research skills through a focussed mentoring program. Presented at Proceedings of International Academic Conferences 2805010, International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences.

Ferris, G. R., Perrewe, P. L., & Buckley, M. R. (2015). Mentoring Ph. D. students within an apprenticeship framework, in S. J. Armstrong and C. V. Fukami., (eds.), The SAGE handbook of management learning, education, and development.: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 271–287.

Gallagher, E. N., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2008). Social support and emotional intelligence as predictors of subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(7), 1551–1561.

Gao, J., Luo, M., & Hu, Y. (2018). How does sipervisors’ capital affect the quality of postgraduate education: data from 15 univerisities in 6 cities. Journal of Education Studies, 14(6), 97–106.

Gu, J., Wang, X., & Wu, J. (2013). The influence of supervisory pattern on graduate students’ creativity: a perspective from internal-external motivation theory. Chinese Higher Education Research, 1, 45–50.

Hagenauer, G., & Volet, S. E. (2014). Teacher–student relationship at university: an important yet under-researched field. Oxford Review of Education, 40(3), 370–388.

Helliwell, J. F., & Barrington-Leigh, C. P. (2013). Measuring and understanding subjective well-being. Canadian Journal of Economics, 43(3), 729–753.

Helliwell, J. F., & Huang, H. (2010). How’s the job? well-being and social capital in the workplace. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 63(2), 205–227.

Hemer, S. R. (2012). Informality, power and relationships in postgraduate supervision: supervising PhD candidates over coffee. Higher Education Research & Development, 31(6), 827–839.

Hofstede, G. (2003). Culture′s consequences: comparing values. Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations Inc: SAGE Publications.

Huang, G. (2010). Favor and face: Chinese people’s game of power. Beijing: China Renmin University Press.

Imbens, G.W. (2015) Matching methods in practice: three examples. The Journal of Human Resources, 50(3), 373-419.

Jack, A. A. (2015). (No) Harm in asking. Sociology of Education, 89(1), 1–19.

Kim, Y. K., & Sax, L. J. (2009). Student–faculty interaction in research universities: differences by student gender, race, social class, and first-generation status. Research in Higher Education, 50(5), 437–459.

Kong, F., Zhao, J., & You, X. (2013). Self-esteem as mediator and moderator of the relationship between social support and subjective well-being among chinese university students. Social Indicators Research, 112(1), 151–161.

Lin, J., & Chao, Y. (2019). Impact of “supervisor-postgraduate fellowship” on the development of postgraduates: qualitaitve research based on informal organization theory. Journal of Graduate Education, 5, 1–8.

Long, Y., & Wang, S. (2018). Effects of student-faculty interaction on students’ learning: analysis the heterogeneity between the first-generation and non-first-generation college students. Higher Education Exploration, 12, 32–40.

Lovitts, B. E. (2001). Leaving the Ivory Tower: the causes and consequences of departure from doctoral study, Maryland: Rowan and Littlefield: Lanham.

Lu, G., & Hu, W. (2015). The effects of student-teacher interaction and peer interaction on the development of undergraduates. Research in Higher Education of Engineering, 5, 51–59.

Lundberg, C. A., & Schreiner, L. A. (2004). Quality and frequency of faculty-student interaction as predictors of learning: an analysis by student race/ethnicity. Journal of College Student Development, 45(5), 549–565.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444.

Meyerson, D., Weick, K.E., & Kramer, H.M. (1996). Swift trust and temporary groups. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations: frontiers of theory and research (pp. 166–195). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nielsen, I., Newman, A., Smyth, R., Hirst, G., Heilemann, B. (2017). The influence of instructor support, family support and psychological capital on the well-being of postgraduate students: a moderated mediation model. Studies in Higher Education, 42(11), 2099–2115.

Paglis, L. L., Green, S. G., & Bauert, T. N. (2006). Does adviser mentoring add value? a longitudinal study of mentoring and doctoral student outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 47(4), 451–476.

Pascarella, E. T., Pierson, C. T., Wolniak, G. C., & Terenzini, P. T. (2004). First-generation college students:additional evidence on college experiences and outcomes. The Journal of Higher Education, 75(3), 249–284.

Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: civic traditions in Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rosenthal, G. T., Folse, E. J., Alleman, N. W., Boudreaux, D., Soper, B., & Von Bergen, C. (2000). The one-to-one survey: traditional versus non-traditional student satisfaction with professors during one-to-one contacts. College Student Journal, 34(6), 315–321.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. F. (1998). Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404.

Santos, S. J., & Reigadas, E. T. (2004). Understanding the student-faculty mentoring process: its effects on at-risk university students. College Student Retention, 3(6), 337–357.

Schoeps, K., de la Barrera, U., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2019). Impact of emotional development intervention program on subjective well-being of university students. Higher Education.

Siedlecki, K. L., Salthouse, T. A., Oishi, S., & Jeswani, S. (2014). The relationship between social support and subjective well-being across age. Social Indicators Research, 117(2), 561–576.

Skvoretz, J., Kersaint, G., Campbell-Montalvo, R., Ware, J. D., Smith, C. A. S., Puccia, E., et al. (2019). Pursuing an engineering major: social capital of women and underrepresented minorities. Studies in Higher Education, 45(2), 1–16.

Su, Z., Su, J., & Goldstein, S. (1994). Teaching and learning science in American and Chinese high schools: a comparative study. Comparative Education, 30(3), 255–270.

Woolston, C. (2019). PhDs: the tortuous truth. Nature, 575(11), 403–406.

Woolston, C., & Meara, S. O. (2019). China’s PHD students give their reasons for misery. Nature, 575, 711–713.

Yang, W., Wei, Y., Shi, Y., Li, M. (2018). The influence of tutor’s guidance style on the innovative ability of graduate students with different levels of initiative:an investigation of nine universities. Fudan Education Forum, 16(3), 74–79.

Yao, T., & Yu, C. (2019). Research on the relationship between peer-supervisor support, research self-efficacy and postgraduates’ research innovation. Higher Education Exploration, 4, 46–54.

Yu, X., Zhao, J., & Wu, X. (2017). Empirical analysis on the status and influence of the supervisor-students relationship in universities. Journal of Tianjin Univerisity (Social Science), 19(2), 157–161.

Yue, C., & Qiu, W. (2019). An empirical study on the employment gaps of college graduates among different disciplines. Journal of Northwestern Polytechnical University (social science edition), 1, 31–39.

Zhang, H., Guo, F., & Shi, J. (2018). On improving first-generation college students’ participation in high-impact educational practices. Educational Research, 6, 32–43.

Zheng, W., & Zhang, C. (2019). Study on the construction of “supervisor-postgraduates” relation based on the perspective of psychological contract. Journal of Graduate Education, 5, 16–20.

Zhou, A. J., Lapointe, É., & Zhou, S. S. (2019). Correction to: Understanding mentoring relationships in China: towards a Confucian model. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 36(3), 903.

Funding

This paper is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71874015, 71974016), and the International Joint Research Project of the Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, China:(ICER202003, CER201905, ICER202005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Measurement tools for students’ subjective well-being

Measurement of positive emotions

Positive emotions are measured with the following three questions. Students were asked to give a score for each one, with 1–7 reflecting their self-perception from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The paper conducts factor analysis on the three questions and then takes score of the first common factor as positive emotion score of the samples.

See Tables 8 .

Measurement of satisfaction

Satisfaction includes five indicators, namely, “interest in the major,” “sense of worth for the major,” “postgraduate education satisfaction,” “postgraduate life satisfaction” and “general life satisfaction.” Among them, the first four indicators use original scores of the survey questions as scores of the corresponding subjective well-being dimensions, while the last indicator is calculated based on Diener et al.’s (1985) scale. The survey questions are as follows:

(a) Question on “interest in the major”: Are you interested in your major? ___ (Choose from 1 to 10, which indicates “not interested at all”-“interested very much.”)

(b) Question on “sense of worth for the major”: Do you think your current major can help you get an ideal job? ____ (Choose from 1 to 10, which indicates “worthlessness”-“great worthiness.”)

(c) Question on “postgraduate education satisfaction”: In general, are you satisfied with the postgraduate education in your university? ____ (Choose from 1 to 100, which indicates “not satisfied at all”-“satisfied very much.”)

(d) Question on “postgraduate life satisfaction”: In general, are you satisfied with your postgraduate life so far? ____ (Choose from 1 to 100, which indicates “strongly dissatisfied”-“strongly satisfied.”)

(e) “General life satisfaction” is measured on the basis of Diener et al.’s (1985) scale and includes the following "five questions (See Table 9)". Students are asked to give a score for each one, with 1–7 reflecting their self-perception from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” This paper makes factor analysis on the five questions and uses score of the first common factor as the score of general life satisfaction of the samples.

Robustness test

This paper categorizes the samples into four disciplinary groups, namely, natural science, engineering, social science and humanities, based on students’ major, and then respectively puts all the relationship variables in each group of samples back to re-estimate equation (1). If the relationship in each discipline is robust and consistent, it would provide support for our causal effect inference based on the whole sample. To make the paper more coherent and focusing, we put the robustness testing in Appendix Table 10.

The estimated results in Appendix Table 10 show that H1a and H1b get supported basically from samples in each discipline. The results convince that robustness of the estimated result in this paper is sound, and so the reciprocity and trust of the SSR indeed have positive impact on the students’ subjective well-being.

Test if the difference between coefficients of SSR’s structure dimension indictors of in first-generation model and non-first-generation model is statistically significant

Although the estimation results in Table 6 show that the structural dimension of the SSR (both the indicators on students’ contribution to supervisors and on supervisors’ rewards on students) has a significant relationship with the first-generation students’ well-being, but the relationship for non-first-generation students is nonsignificant. It provides intuitive evidence that decreasing contribution of students to supervisors and in turn improving reciprocity level of the SSR may play a more important role in enhancing the subjective well-being of the first-generation students, but it needs statistical support. In order to test whether the difference between coefficients of SSR’s structure dimension indictors in first-generation group and those in non-first generation group is statistically significant, we estimate the following regression model:

In the equation above, the 4 structural dimension variables (stru_relaionr) and their interaction terms with “first-generation students” (\({\mathrm{stru}\_\mathrm{relation}}_{\mathrm{r}}\times \mathrm{first}\)) are key explanatory variables, while all the control variables and the affiliation dimension of SSR are introduced. Then, we can test H3a by analyzing value and significance of the interaction term coefficient \({\stackrel{\sim }{{\varvec{\rho}}}}_{{\varvec{e}}}\) more precisely.

The estimation results are reported in Appendix Table 11. The results show that the coefficients of interaction term “Time of working for supervisors weekly× first-generation student” are significantly negative in model (1)–(3). Such results mean that the difference between the coefficients in different samples (in first-generation students and in non-first-generation students) is indeed significant. Hence, we could get the conclusion “H3a gets support to some extent” in our article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, W., Liu, S. & Zhao, C. Impact of student-supervisor relationship on postgraduate students’ subjective well-being: a study based on longitudinal data in China. High Educ 82, 273–305 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00644-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00644-w