Abstract

Happiness and well-being at work has been an increasingly popular topic in the past two decades in academic and business contexts alike, along with positive psychology, through which organizations aim to find out, what makes working environments engaging and motivating. Few studies have focused on education, however, especially from a solution-focused perspective, even though it is a sector where employees are highly exposed to stress and burnout. Accordingly, the purpose of his study was to investigate the relationship between teachers’ psychological resources through the concept of psychological capital, workplace well-being and perceived workplace happiness. We used both qualitative (open-ended question) and quantitative (test battery) methods to examine the relation between the various factors. Content analysis of responses in our qualitative research suggests that the main pillars of teachers’ workplace happiness were realization of goals, feedback, finding meaning in work and social relationships. The results of our quantitative study indicated that workplace well-being and happiness correlated with inner psychological resources, hope and optimism in particular. We conclude that the future focus on employee well-being must take into account positive contributing factors and adopt a positively-oriented approach to promoting well-being. Suggestions for practical implications are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The mental health and well-being of employees are crucial factors in an organization’s performance and success (Page and Vella-Brodrick 2009). The dynamics of employee well-being at work are pivotal for understanding the different components that affect their health, work behaviour and performance. There are resources on individual, group, managerial and organizational levels that are strongly related to employee well-being (Nielsen et al. 2017). Subjective well-being is connected with levels of workplace stress, absenteeism, intrinsic motivation, commitment, innovation, and satisfaction. Work-related well-being and workplace happiness have been identified as important factors in performance, job satisfaction (Crede et al. 2007; Fisher 2010), and susceptibility to burnout (Iverson et al. 1998). Organizational programmes designed to reduce negative workplace outcomes like burnout or stress are often risk-based, problem-focused and negatively framed approaches to mental health (Page and Vella-Brodrick 2012; LaMontagne et al. 2007). There are far fewer positively framed programs or interventions that aim to promote and to improve positive and inner aspects of employees’ well-being at the primer level (LaMontagne et al. 2014; Luthans 2002a). Thus, the contributory factors of employee workplace well-being and happiness should be considered very important components of mental health and subjective well-being per se.

Well-Being and Happiness

Previous literature on subjective well-being proposed that well-being should be considered a broader phenomenon that involves affective, cognitive and behavioural aspects (Ryff 1989; Ryff and Keyes 1995; Seligman 2011). There are two main approaches to the concept of well-being: subjective well-being and psychological well-being. Subjective well-being is often used as an umbrella term covering various factors. Although there is a consensus that well-being is a multidimensional construct, different theoretical interpretations of the components have been proposed. Constructs of happiness and subjective well-being focus mainly on hedonic aspects of well-being – striving for maximisation of pleasure and positive emotions, but other constructs include eudaimonic aspects as well, such as autonomy and self-actualization (Fisher 2010).

Several theories of psychological well-being fall under the broader concept of eudaimonic well-being. One of them is the self-determination theory (SDT) formulated by Ryan and Deci (2000), who came to the conclusion that there are three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence and relatedness. When these needs are satisfied, they foster well-being. Ryff (1989) analysed various approaches to happiness in different subfields of psychology and introduced a six-dimensional model of well-being comprising the following factors: self-acceptance, environmental mastery, autonomy, positive relations with others, personal growth, and purpose in life. Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of autotelic personality also fits into the term of eudaimonic happiness. Autotelic individuals often engage in meaningful activities for their own sake (Csikszentmihalyi 1990; Baumann 2012). Finally, in a positive psychological context, Seligman’s (2002) authentic happiness model distinguishes three types of lives that together make up an all-round happy life: a pleasant life, an engaged life and a meaningful life. Later Seligman (2011) revised his early model of happiness and in a new well-being theory proposed five pillars of human flourishing: Positive emotions, Engagement, positive Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment (PERMA as an acronym). According to Seligman (2011), each of these five elements contributes to well-being and is pursued for its own sake.

As can be seen above, multidimensional approaches to well-being may not only provide a more precise interpretation of well-being but may also provide a better basis for the design of interventions aimed at improving well-being and happiness. Notably, psychological well-being is a concept that can also be interpreted and measured in organizational context (Dagenais-Desmarais and Savoie 2011).

Well-Being and Happiness at Work

The past few decades have seen an explosion in research on workplace happiness. Many authors have attempted to identify the sources of happiness and each of them has found important but different determinants (e.g. Diener 1984; Freedman 1978; Argyle 1987; Csikszentmihalyi 1990; Emmons 1986). Subjective well-being is often equated with happiness. Happiness is one of the most studied facets of well-being, but is only one of the various aspects that researchers have considered (Jayawickreme et al. 2012).

Workplace happiness is a term that describes the experience of employees who are energized by and enthusiastic about their work, find meaning and purpose in their work, have good relationships at their workplace, and feel committed to their work. Overall or global workplace happiness refers to how employees evaluate their work life in general and most studies rely on global reports of this kind (e.g. Kahneman et al. 2004). Most studies have examined objective variables that influence well-being and happiness, but happiness can also be interpreted through a subjectivist approach, which considers happiness from the individual’s own perspective, and this notion has led to the self-report measurement of global happiness (Lyubomirsky and Lepper 1999).

Dolan and his colleagues (Dolan et al. 2008) studied 19 cross-national, major national datasets that included measures of subjective well-being and tried to identify all the potential influencers of well-being. Their analysis revealed seven broad categories: 1. income, 2. personal characteristics (age, personality), 3. socially developed characteristics (education, unemployment), 4. how we spend our time (e.g. caring for others, hours worked), 5. attitudes and beliefs toward self/others/life (religion, political persuasion), 6. relationships (intimate relationship, having children), and 7. the wider social, economic and political environment (degree of democracy, welfare system). Dolan et. al’s review highlighted the most frequently measured factors associated with well-being and was concerned chiefly with the impact of objective and subjective variables which in combination influence overall well-being. In our study, we adopt a subjectivist interpretation where overall subjective happiness denotes a broader and more global psychological phenomenon.

Many studies have shown that overall well-being and happiness at the workplace can be highly beneficial for organizations (Seligman 2002). Research has shown that happier individuals tend to have better physical and psychological health, and live longer (Roysamb et al. 2003; Lyubomirsky et al. 2005a, b), perform better, can cope better with stressful events (Wood and Joseph, 2010), have more positive workplace relationships and are more satisfied with their jobs (Boehm and Lyubomirsky 2008; Connolly and Viswesvaran 2000). Individuals with higher levels of well-being perform better at work, are more cooperative (George 1991), have more satisfying relationships, stronger immune systems, fewer sleep problems, lower levels of burnout, greater self-control, better self-regulation and coping abilities, and are more prosocial (Diener and Seligman 2002; Chida and Steptoe 2008; Seligman and Schulman 1986; Seligman et al. 1990; Kubzansky et al. 2001; Fredrickson and Joiner 2002; Howell et al. 2007; Lyubomirsky et al. 2005a, b; Segerstrom 2007; Williams and Shiaw 1999).

Teachers’ Well-Being and Happiness

The psychological capacities of individuals can be especially important in a professional context. Teaching is a profession which is highly associated with stress-related outcomes and teachers’ stress and burn-out are popular topics of research. Nevertheless, studies primarily focus on problems, like burn-out, stress, frustration, anxiety, attrition (e.g. Singh and Billingsley 1996; Kyriacou 2001; Brouwers and Tomic 1999; Trent 1997; Macdonald 1999; Ramsey 2000) while there are fewer solution-focused, positively framed approaches that build on teachers’ strengths or intrinsic resources linked to well-being. The workplace well-being and happiness of teachers have been investigated less often than other factors, although there are some relevant and remarkable results (Calabrese et al. 2010; Hoy and Tarter 2011; Benevene et al. 2018; Chan 2009; Chan 2010; Lavy and Bocker 2018). According to Hoy and Tarter (2011), positive psychology can be a new frame in which educational staff’s well-being can be improved.

In the context of teaching, research has shown that teachers’ happiness and well-being correlates with students’ well-being and performance. Briner and Dewberry (2007) found a relationship between staff well-being and student SATs (Statutory Assessment Tests) although a causal relationship could not be proved. Some studies show that teachers’ well-being is closely related to students’ school performance and happiness (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005a, b; Jennings and Greenberg 2009). Other studies have revealed that teachers’ happiness has an impact on students’ happiness (Bakker 2005). Jennings and Greenberg (2009) emphasized the importance of teachers’ well-being in developing and maintaining a positive classroom climate and the teacher-student relationship. Roffey (2012) argued that focusing on teacher well-being also promotes student well-being and performance. Spilt et al. (2011) discussed empirical evidence for the influence of teacher-student relationships on teacher well-being.

Despite limited research results regarding the link between teachers’ well-being and students’ attainment, there is a reasonable expectation that such a relationship exists. It seems reasonable to assume that teachers with a high sense of well-being would presumably perform better, display better educational outcomes and that this would lead to happier and more motivated students. Bricheno et al. (2009) highlighted that more research needs to be conducted into the link between teacher well-being and student educational attainment and well-being. Teacher well-being should be actively supported in schools.

There is a substantial body of evidence relating to factors that enhance well-being. To date, many studies have mainly targeted the negative side of the teaching profession including work stress and burnout. This focus on the negative aspects of teachers’ mental health provides no guidance on how to promote and develop overall well-being. By adopting a positive psychological approach, a new perspective opens as the primary focus shifts to revealing and developing potential and inner resources rather than treating problems or negative consequences.

Positive Psychological Resources

Positive psychology offers a new perspective on improving well-being and happiness without solely focusing on deficits and disorders. This notion includes building upon existing resources and strengths that individuals possess such as optimism, hope, resilience, or gratitude, that can help to sustain good mental health (Seligman et al. 2005; Peterson and Seligman 2004; Luthans et al. 2006). Most of the research focused on employee well-being originates from Positive Organizational Scholarship (POS; Cameron et al. 2003) and Positive Organizational Behaviour (POB; Luthans 2002b). POS and POB research have demonstrated that well-being at work is more than the result of job satisfaction and commitment, and that well-being includes “positively oriented human resource strengths and psychological capacities” (Luthans 2002a, p. 59). The concept of psychological capital (PsyCap) refers to an individual’s positive psychological state of development characterized by hope, self-efficacy, resilience and optimism (often referred as the HERO model from the acronym of the components) (Luthans et al. 2007). PsyCap is malleable, and therefore open to development. This notion also opens new opportunities for workplaces to enhance employee well-being (Avey et al. 2011). This positive approach suggests that revealing and promoting resources and strengths that individuals already have can improve their overall well-being and happiness, as well as having a positive impact on the organization’s productivity and on other (not necessarily measurable) outcomes (e.g. workplace climate, cooperation between employees, trust in leaders). The more inner resources individuals have, the more likely it is that they will experience higher levels of motivation, satisfaction and well-being (Xanthopoulou et al. 2007).

Some remarkable research results in recent years have demonstrated the relationship between PsyCap and well-being. For example, Culbertson et al. (2010) found that PsyCap was related to both (hedonic and eudaimonic) types of well-being. This finding suggests that PsyCap may be a core element in the application of positive psychology in organizations, and that improving employees’ PsyCap may be one of the most effective ways to enhance workplace well-being. Research has shown that micro-interventions or even Internet-based interventions (aimed at developing hope, self-efficacy, resilience and optimism) can improve PsyCap (Luthans et al. 2006; Luthans et al. 2008). These encouraging results may provide a suitable starting point when considering broader well-being interventions in organizations.

We approach teacher well-being within the positive psychology framework to give us a more comprehensive understanding of what factors may play significant roles in the formation of teachers’ well-being. For this reason, we use the multidimensional PERMA model as a basic framework. In this study, we explore teachers’ psychological capital in relation to workplace well-being and happiness. We assume that different PsyCap factors relate distinctly to different facets of well-being and overall workplace happiness. Applying the PsyCap model and the multidimensional PERMA model can help us to understand which aspects are the most relevant for overall happiness. We aim to reveal the unique contribution of each PsyCap component to each of the PERMA factors, as well as to overall workplace happiness. Our research was guided by the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the sources of teachers’ workplace happiness? What are the elements that contribute to overall happiness at work?

-

2.

How do different PsyCap factors relate to each of the PERMA facets? Do some factors of PsyCap have a stronger link to overall workplace happiness?

-

3.

Which dimensions of PERMA play a role in overall workplace happiness? Do some facets of PERMA have a stronger link to overall workplace happiness?

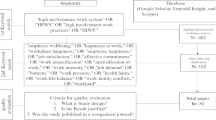

Method

Participants

297 participants completed the Workplace well-being and happiness questionnaires (201 female, 93 male, three respondents did not indicate their gender). The mean age of the participants was 41.4, with a standard deviation of 7.81 and most participants were between 36 and 45 years of age. All the participants had university or college degrees. The relationship status of participants was also recorded: 207 were married, 50 single, and 36 divorced or widowed (4 participants did not respond). 65 of the participants had 1 child, 123 had two, 40 had three, 6 had four, 1 had five, and 60 had no children (2 persons did not respond).

The cohorts were participants in Educational Leadership training at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics’. This is a postgraduate course to get a qualification in the field of leadership that lasts for two years. This qualification is necessary to become a principal of any educational institute. Participants were recruited before the training session has started. The conductor of the research gave them all the information about the aim of the research personally. They received information about the opportunity to participate from the conductor of the research, therefore taking part was voluntary. Volunteers filled the questionnaires after the training session has ended.

The questionnaires were completed by teachers working at elementary (39,7%) and secondary (28%) schools, kindergartens (15,1%), art schools - music, dance, crafts - (9,4%) and special education teachers (7,8%) working for pedagogical professional services.

Measures

The participants in the study were asked to rate their workplace happiness, well-being and psychological capital on scales as a pilot study for future international research. The results of both quantitative and qualitative measures were then analysed.

Qualitative Method – Content Analysis

The aim of this research was to explore the determinants of workplace happiness via content analysis of teachers’ answers written to the open-ended question: “When do you feel/experience happiness at work?” Given that happiness is defined as a subjective phenomenon, our aim was to explore what teachers identified as the main factors that determine their workplace happiness experience in their own words, and accordingly this open-ended question was asked before the rest of the test battery. The first questionnaire, the Subjective Happiness Scale, included an instruction for participants to record responses according to their current workplace and full time job context.

Quantitative Measurements

Seligman’s PERMA model was used as a framework for measuring workplace well-being. We use a measurement that was developed on the basis of this model (Kun et al. 2017). Although the PERMA model focuses on positive aspects of well-being, this measurement also captures the negative side of workplace well-being. The Workplace PERMA Questionnaire comprised 6 dimensions: Positive emotions, Engagement, positive Relationships, Meaning of work, Accomplishment, and Negative aspects of work. Respondents had to record their answers on a 5-point Likert scale. The scale had a Cronbach α of .87, which indicated that the scale was reliable for the sample.

Psychological capital was measured using four different questionnaires. Resilience was measured using the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS; Smith et al. 2008). For the Hungarian sample, our own translation of this scale was used. The scale contained 6 items, of which 3 are positive and 3 are negative items. Respondents recorded their answers on a 5-point Likert scale. The scale’s Cronbach α of .80 showed that the scale was reliable for the sample. Self-efficacy was measured using the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE; Schwarzer and Jerusalem 1995), for which we also used our own translation. The scale consisted of 10 items, which respondents had to record their answers for on four-point Likert scales. The scale’s Cronbach α of .82 showed that the scale was reliable. The validations of the Hungarian versions of BRS and GSE scales are currently in progress. After the translation of these two scales into Hungarian we translated a completed translation back into English, compared that new translation with the original scales, and finally, reconciled any meaningful differences between the two.

Optimism was measured with the Life Orientation Test – Revised (LOT-R; Scheier et al. 1994), the Hungarian translation of which was developed by Bérdi and Köteles (2010). The scale consists of 10 items, including reverse items for pessimism. Respondents had to record their answers on a 7-point Likert scale. The scale’s Cronbach α was below .70, therefore the 8th item had to be omitted, after which the scale had an α-value of .70, and therefore proved to be reliable. Hope was measured on the Adult Hope Scale (AHS; Snyder et al. 1991). The scale contains 12 items, and two subscales: Agency (motivation to reach a goal, and the amount of energy focused on the goal), and Pathway (the personal ability to find solutions and if the goal is being seen as a stressor or challenge), measured by four items on each subscale. Four distractor items were also added to the scale. The Hungarian translation was developed by Martos et al. (2014). Respondents had to record their answers on an 8-point Likert scale. The Pathway subscale had a Cronbach α of .71, while the Agency subscale had an α of .70. The overall scale had a Cronbach α of .80 confirming its reliability. Finally, overall workplace happiness was measured by means of the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS; Lyubomirsky and Lepper 1999) which consists of four items. As a Hungarian translation was not available at the time of research our own translation was used and followed the same translation process we mentioned above. Respondents had to record their answers on a 7-point Likert scale, where only the highest and lowest values were labelled within each item. In the instructions, participants were asked to answer questions specifically regarding their workplace experiences. The scale proved reliable in translation and as applied to the sample with a Cronbach α of .81.

The last section of the set contained socio-demographic questions on gender, age, relationship status, number of children, highest level of education and employment status, and also single questions about work and life satisfaction, stress at work and overall health status. The questions about life and work satisfaction and workplace stress were measured on a 3-point scale, while overall health status was measured on a 5-point scale. These questions were included to further explore if the (positive or negative) correlation between these factors and happiness can be proved. Previous Hungarian studies had examined the relation of these factors and overall well-being among healthcare professionals and educators (Deutsch et al. 2015; Holecz and Molnár 2014), but not specifically applied to the happiness experienced by teachers. However, since overall well-being and happiness are both positive constructs, we expected similar results. The surveys were conducted at the training venue.

Results

Content Analysis – Exploring Workplace Happiness Factors

In the content analysis procedure the teachers’ answers to an open-ended question were defined as a text unit, and “that part of the text unit to which coding categories or dimensions are applicable” (Smith 2000., p. 320) were categorised as a coding unit.

We used linguistically defined segments (sentences, clauses, phrases, words) as coding units. The most important aspect of the text used as coding unit is the theme, that is a single idea or statement about the topic (here: about workplace happiness). A theme may be expressed in a few words, a phrase, or sentences. Each theme in a text unit was classified by its properties and then classified. We did not have a priori categories, but instead inductive, empirical ones were created for every theme that appeared to warrant classification as a new one. By using an inductive approach, categories emerge from the material without any preconceptions. Since our qualitative research tends to be exploratory, this approach seemed to be most appropriate for our research question.

Two coders analysed the written answers from 297 respondents independently to create coding categories, with the criteria of uni-dimensionality, comprehensiveness, mutual exclusivity and independence (Smith 2000). Frequency scores for categories were calculated by adding the number of themes that represented a given category. Categories were retained if the intercoder agreement was at least 80% and if each of the coding units had more than five recorded (or coded) units. To avoid overestimation of the agreement we also included frequency occurrences and non-occurrences. We provided the validity of the content analysis along three criteria:

-

1.

Closeness of categories: two coders independently coded the study sample of 297 workplace happiness descriptions and empirical categories were retained if they arrived at an agreed upon definition of each specific categories. We excluded categories from the final analysis that was not agreed upon.

-

2.

Data validity: our data accurately reflect the range of content being studied. Our measuring procedure represented the intended, and only the intended, concept.

-

3.

Internal validity: a) our categories are exhaustive and mutually exclusive b) and we measured our workplace happiness concept with categories that are the highest level of measurement possible.

The answers given to the workplace happiness open-ended question varied in length from one to 48 words. We summarized a total of 762 responses (sentences, phrases, words) given to the open question, and finally, 673 coded units were classified into categories. As a result, four distinct main dimensions, and within them, 21 subcategories were defined (Table 1). Subcategories describe the content of the main ones in a more detailed way. The four main dimensions are as follows:

-

1.

Results and success

-

2.

Assessment of and feedback on the work

-

3.

Meaning at work

-

4.

Social relationships

Table 1 Frequency and mean of coded units and weighted means

Results and Success – Past, Present, Future

The first subcategory refers to success, mainly to results achieved by the teachers (“The students understood the curriculum.”). These results are the confirmation of good work and enhance teachers’ well-being, and as positive results affect not only their emotional experiences but also serve as a basis for future motivation and successes (Tadić et al. 2013). As a second subcategory, teachers have a sense of inner, subjective competence and self-efficacy as they feel that they are able to perform tasks that match their skills, and motivate them to perform well (“Using my skills and knowledge I did the best I could.”). All of these ensure the sense of achievement and enjoyment of success and in turn contribute to the sense of efficacy (Friedman and Kass 2002). Not surprisingly, performance and success are also specifically related to children’s’ success. This is the third sub-category within the category of success. The answers to this question cover past, present and future - it is not only about the work done in the present but also covers feedback from children on past performance (“ ...my old students come back to school and tells me how valuable the knowledge he has gained from me”), and about the hope that can be linked to the future (e.g. that a child will be successful in an entrance exam). This time continuity is ensured by a sense of success and effective work that includes not only retrospective but also positive and future-inspired confidence. All these aspects are significant contributors to the sense of personal well-being (Zee and Koomen 2016). In the fourth subgroup, there is a general motive for success, and another is related to the professional side (“I did a very good job professionally and methodologically.”). These can be related to the concrete results achieved, joint work with their students and colleagues and success experienced at a subjective level (“I have a sense of success.”). A separate dimension of successes and achievements of school life can be defined, such as social events, applications for funding or projects, competitions, celebrations, and other programs (“My students won prizes in a contest.”, “Our school won a tender.”). The presence of this category clearly indicates that the (workplace) community is an important element of personal well-being (Gross and John 2003), as no one works in isolation but on a collective level, and shared goals and experiences are as positive as achieving personal goals. Individual prosperity and happiness can only be imagined in an organization that is supportive, and in addition to individual endeavours, it provides strong attachments and builds a community. Experiences shared by colleagues and teams may enhance the individual’s level of well-being (Greller et al. 1992; Sonnentag 1996). In the main category of success, the next subgroup is also related to children, which includes one of the important goals of teacher work: the development of children. This refers both to work with children in usual, everyday education situations, or to children with problematic abilities, and can also be considered when a child with ‘problematic personality traits’ changes in a positive way (I taught to read a little kid everyone has given up about.”). The importance of developing not only the abilities but the personality of children is also part of this category, and this development-centred work can be an indicator of teachers’ work and a sense of personal well-being. The last key element of the first major dimension is the realization and implementation of goals and plans, which may be short or long-term, and may be more general or specific (“When I can effectively implement my plans.”, “I am satisfied when each work phase works as I planned.”). These are direct, sometimes measurable indicators of success, as they demonstrate the individual’s competence, efforts and commitment to goals, which, as a source of motivation (Locke and Latham 2002), provide a further basis for future goals and aspirations.

Assessment of and Feedback on Work

The first major sub-category of the second dimension is feedback, and most of all, positive feedback on job performance. The number of responses about positive feedback (Mitchell et al. 1982) is outstanding since they account for more than half of the total number of responses in this dimension (140). Its robustness is also reflected in the fact that not only global, generally work-related feedback, but also positive, confirming, acknowledging feedback is determinative. Further analysis revealed that teachers stress the importance of feedback from students, parents, colleagues, and leaders alike content (“I get positive feedback from children, parents, and colleagues.”). Feedback can be direct (either verbal or nonverbal) and indirect feedback (e.g. the success of a child or a child winning a contest can be considered the result of the contribution of a teacher). The next subcategory concerns moral recognition and the appreciation of teachers’ work. As with the previous category, there is a general level of recognition from students, colleagues, parents, and leaders (“I get appreciative words from my colleagues or from the school principal.”). The value of moral recognition and appreciation is obvious, and studies have shown that it can have a much stronger effect on performance and commitment (to the workplace) than financial benefits (e.g. Brun and Dugas 2008). The third category within this main dimension is the satisfaction expressed by others (superiors, colleagues, students, etc.), but this sub-category also represents personal, subjective satisfaction (“I am satisfied.”,“My colleagues are satisfied with my job.”). Satisfaction has a striking effect on workplace happiness because of its emotional component since it directly contributes to the subjective sense of well-being of individuals (Bowling et al. 2010). The coding units of the next sub-category, labelled praise, appear not only in general but also on a specific level specifying who (leader, co-worker, parents) the praise is given by. Praise is also a type of the social reinforcement, which has a direct impact on motivation since it is the direct and socially awarded expression of maximum recognition (Deci and Ryan 1985; Sansone et al. 1989). It is a highly rated form of the reinforcement of good performance. In the penultimate sub-category within the second main dimension, there are coding units that confirm the respondent as a member of a particular workplace, organization, that counts on and considers a person an important part of it and takes into account his/her opinion. This sub-category was labelled organizational citizenship, referring to the fact that the employer considers his/her employee a full member of the workplace and appreciates his/her contributions to the organizational goals and values (“They consider my job important and make me feel that what I do is required to the success of the school.”). Organizational citizenship is an important key factor of workplace engagement (Bhatnagar and Biswas 2010), and without it, the worker feels as if they are only a tiny cog in the machine, which if lost, can easily be replaced by another. Finally, the last sub-category includes financial recognition and reward, which naturally includes salary (“I would be lying if I said finances do not cause happiness but is not what matters the most.”). It is worth mentioning that there were only a few coding units in this category, this sharp difference is notable in itself: there are 29 coding units that refer to the importance of moral recognition and only 6 units to the importance of financial recognition. Apart from social incentives, it is understandable that financial incentives are also important, but it is worth pointing out that teachers do not have exclusively or primarily financial incentives, but instead moral and social motivational factors play an essential role in the formation of their well-being and happiness.

Meaningful Work – Meaningfulness and Emotion

The first and most significant among the five sub-categories of this dimension is the well-being, joy and happiness of the children. This refers to the times when children enjoy the lesson, learning, tasks, and when they give positive feedback to the teacher (“I see the joy on the children’s faces.”, “Students give feedback that they had a good time in my class.”). Positive emotions (pleasure, enthusiasm, excitement, enjoyment) expressed by children and shared with the teacher are significant components of a teacher’s well-being (Spilt et al. 2011). The second sub-dimension that is also related to the children concerns rises in children’s motivation and interest (“I see genuine interest on my students’ faces.”), and which includes changes in attitude (from passive to active), and increased desire to be praised and to learn. This is one of the main missions of pedagogical work, as one of the greatest challenges for teachers is to raise children’s interest, curiosity and motivation to learn. The next subcategory representing an important determinant of a teacher’s happiness is that his/her work had or has meaning. The most essential aspect of this category is that the teacher does not perform irrelevant, often unnecessary (e.g. administrative) tasks, but instead real and valuable pedagogical work is carried out. An important criterion for meaningful work is that the employee feels that his/her work is significant, useful, and influences others in a positive way, and is also undertaken for unselfish reasons (Pratt and Ashforth 2003). This subjective meaning and personal significance are very important determinants of an individual’s work-related well-being, as is evident here. The transfer and sharing of knowledge, defined as a separate sub-category, is one of the key tasks of pedagogical work, which includes the success of knowledge and information transfer processes during lessons, when children understand the material being transmitted. This sub-category also includes success in approaching, working on and completing the tasks teachers are set. The last category covers the special state and characteristics associated with teachers’ experiences while conducting everyday classroom work, which we could actually call flow at work. Flow is an optimal psychological state where attention is undivided and motivates action to fulfill the goal of expressing self (Csikszentmihalyi 1990). On the one hand this is when a teacher has flow in his/her work (“I work with intrinsic motivation and experience flow.”); on the other it is when a teacher triggers flow-like experience in children. In the happiness texts we can detect features of flow, such as work is carried out smoothly and almost unnoticed (“The whole class becomes one unit no child is left out of attention.”); time passes unnoticed (“Time spent together flies.”); they enjoy tasks (“Kids enjoy the task.”); there is a chance for a relaxed and creative manifestation; and there are a lot of smiles and laughter. In a state of flow teachers have a sense of self-efficacy and they feel that they are at the apex of their abilities professionally and methodologically.

Social Relationships

The three sub-categories of Social relationships display the highest weighted means. The first subcategory covers the love, emotional attachment, and positive emotional feedback children express toward teachers (“I feel the love, trust, and attachment of the children”). Positive emotional reinforcements from others are essential building blocks of subjective well-being and are important determinants of happiness (Ryff 1989). The more commonly an individual experiences positive emotions, the more they feel others’ acceptance and support, the better their personal well-being and the more efficiently they form and maintain their relationships (Kahn et al. 2003). In the case of teachers, it is no coincidence that social reinforcements from children, who are at the centre of their activities, play such an important role. The second sub-category involves teachers’ relationships with colleagues and the workplace climate. Like the previous child-centred category, relationships are still in focus. The coding units here cover positive, balanced, well-functioning relationships with colleagues (“I am happy to work with my colleagues they are like a second family to me.”) and on an organizational level a positive, supportive climate and a positive emotional milieu (“The workplace atmosphere is good, relaxed, and cheerful.”). The quality of relationships at work often represents an important reason for retention, as well as contributing to job satisfaction and workplace commitment (Crosby 1982; Venkataramani et al. 2013), and as a whole, provides a strong basis for individual and collective achievements and successes. The third and last sub-category of this main dimension concerns social support and co-operation (We help each other, if a colleague has a problem.”, “We work together in a good mood to achieve our goal.”). Helping and supporting colleagues, as well as sympathy and acceptance from colleagues, are an essential part of this category. Selfless help and co-operation in problem management or in finding solutions provide shared (emotional, behavioural) experiences that keep the community together and provide a safe, trusting milieu for the individual. Helping others is not only a pleasure for an individual but gives a sense of meaningful contribution to a community that is also an important building block of subjective well-being (Mitchell et al. 1982; Aknin et al., 2013a, b).

Quantitative Analyses

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive information for each of the scales included in the study (N = 297). As can be seen, participants were above the neutral level for all measurements except the optimism scale (LOT-R).

At the time of data analysis no reference means were not available for all instruments. Some of the measurements (Acton and Glasgow 2015; Aknin et al. 2013; Avey et al. 2011) have not yet been validated in Hungarian, therefore we used our own translations, and the PERMA questionnaire (Baumann 2012) is relatively new (published in 2017 by Kun et al.) therefore it still lacks reference means. Two scales are validated in Hungarian (Argyle 1987; Avanzi et al. 2012), the reference means for these questionnaires are as follows: LOT-R: 3.25 (Bérdi and Köteles 2010), AHS: 5.79 (Martos et al. 2014). As can be seen our particular sample’s means slightly differ from these values.

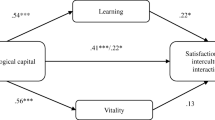

Correlation Analyses

Bivariate Pearson correlations (two-tailed) were deployed to test our research questions 2–3. Correlational analyses were conducted between each dependent variable, including all scales of PsyCap, and the two subscales of AHS. All correlations between variables can be found in Table 3. Our second research question concerned the relationships between the PsyCap and PERMA subscales and SHS. Moderate positive correlations were found between the PsyCap and the overall PERMA scale (r = .52), and between the PsyCap and all the PERMA subscales (.23 < r < .55). Positive Emotions and Achievement showed the strongest relationships with PsyCap subscales, with Positive Emotions having a moderate correlation with LOT (r = .44) and weak correlations with AHS (r = .34) and the Agency subscale of AHS (r = .32). Achievement showed moderate correlations with GSE (r = .45), LOT (r = .40), AHS (r = .55), and the Agency (r = .56) and Pathway subscales of AHS (r = .41).

PsyCap in general showed connections with different subscales of PERMA, displaying moderate correlations with Achievement (r = .56) and Positive Emotions (r = .44), and weak correlations with Engagement (r = .34), Meaning (r = .32), and Positive Relationships (r = .23). The results also suggested that PsyCap was positively and significantly related to SHS (r = .50). Thus, the findings indicate that Psychological Capital factors have a positive relationship with all the workplace well-being factors and overall workplace happiness.

Upon the examination of separate scales of PsyCap, GSE showed strong correlations with AHS (r = .66) and the AHS Pathway subscale (r = .66), moderate correlation with the AHS Agency subscale (r = .49), and weak correlations with BRS (r = .35) and LOT (r = .32). LOT displayed moderate correlations with PERMA (r = .49), SHS (r = .56), and AHS (r = .41), and weak correlations with the AHS Agency (r = .39) and Pathway subscales (r = .35), and with BRS (r = .36). Furthermore, AHS yielded weak correlations with BRS (r = .34), PERMA (r = .39) and SHS (r = .36), while the Agency subscale displayed weak correlations with PERMA (r = .35) and SHS (r = .35), and the Pathway subscale showed weak correlations with BRS (r = .37) and PERMA (r = .32).

Our third research question concerned the relationship between PERMA and SHS. A positive and significant relationship was found between them (r = .47), thus supporting our third research question. SHS also showed a moderate correlation with Positive Emotions (r = .46) and a weak correlation with Achievement (r = .36) and Meaning (r = .31).

Discussion

Teachers are important persons who contribute to student achievement and success (Stronge et al. 2004). Teachers’ workplace happiness and well-being is therefore a critical factor in positive education (Ross et al. 2012). The aim of this study was to reveal the most relevant workplace happiness factors and to understand teachers’ well-being in detail in the framework of the PERMA model and Psychological Capital theory.

We used both qualitative and quantitative methods. After coding nearly 300 respondents’ written workplace happiness texts it became clear that a wide range of essential factors contributed to workplace happiness. Answers were organized into four main dimensions and 21 subcategories. Most of the responses referred to results (e.g. realization of goals and plans) and experiences of success such as successful work, the success of children, and success of the school. This implies that the success of others is as important for teachers as their own individual success in producing workplace happiness. Respondents frequently mentioned the importance and significance of assessment of and feedback on their work. This second main category included moral and financial recognition, praise, and other people’s satisfaction with the teachers’ work, as well as their own feelings of satisfaction. Countless studies have revealed and confirmed the decisive role played by feedback on work, and its impact on performance, commitment to the organization, satisfaction and motivation (Kluger and DeNisi 1996; Eccles and Wigfield 2002). As regards the third main category, teachers’ answers supported the importance of meaningful work in relation to the sense of workplace happiness. Intrinsic reasons for working and finding meaning in work have a positive effect on subjective well-being (Winefield and Tiggemann 1990). Our results have demonstrated that perceiving work as meaningful appears to play an important role in teachers’ happiness. Meaning is derived from different aspect of teachers’ work such as knowledge sharing, interesting and motivating the children, and experiencing flow in their work. The last main dimension referred to social relationships with children, colleagues, and parents. Analysis of teachers’ responses revealed that not only good personal relationships but also a positive overall workplace climate is necessary for workplace happiness. Social relationships, then, are necessary for happiness (Diener and Seligman 2002). The people around teachers provide social support and teachers place a high importance in relationships as sources of happiness.

Our study used six additional questionnaires to explore the relationship between teachers’ well-being, happiness and their inner psychological resources. The data supported our research questions. Correlations showed significant relationships between the variables with the findings revealing that workplace happiness relates positively with all psychological capital factors (hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism; .23 < r < .57) and all well-being dimensions (positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, meaning, and achievement; .19 < r < .46). Optimism (of PsyCap) and positive emotions (of PERMA) were the most relevant factors in relation to workplace happiness (r = .57 and r = .46, respectively). In terms of Frederickson’s (Fredrickson 2001) broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, these findings support the notion that the implementation of interventions to improve optimism and positive emotions may increase happiness. According to this theory, positive experiences and emotions create a positive spiral generating more positive thoughts, experiences and feelings that are beneficial for well-being and happiness. Experiencing positive emotions regularly can produce long-term changes in individuals’ personal resources.

We also found that two of the PERMA subscales, positive emotions and achievement, have the strongest relationship to psychological capital. More precisely, positive emotions are strongly related to optimism while achievement is related to self-efficacy and the two subscales of hope (agency and pathway). This result is consistent with the foundation of hope theory (Snyder 2002) which claims that a pathway involves the future potential to achieve goals, and agency involves motivation for movement along a pathway toward achieving. Not surprisingly, teachers’ achievement is essential for their subjective well-being and happiness at work as our content analysis has also confirmed above.

Our results strongly support the Acton and Glasgow (2015) approach to teacher wellbeing, which is defined as “an individual sense of personal professional fulfilment, satisfaction, purposefulness and happiness, constructed in a collaborative process with colleagues and students” (p. 101).

Practical Considerations

Our research suggests that several important factors can influence happiness and well-being in the workplace specifically. In the light of positive psychology and the potential role of ‘positivity’ as an added value, it is worth reviewing some of the potential activities that may be useful for teachers in order to improve their overall well-being. These possible activities of intervention are selected from the toolkit of positive psychological interventions (PPIs).

There are many forms of positive psychological interventions aimed at improving happiness and well-being – including in the context of work and organizational settings (Layous et al. 2014; Lyubomirsky et al. 2005a, 2005b; Seligman et al. 2005). The aim of PPIs is to identify, develop and broaden individual trait-like characteristics such as the elements of psychological capital and to promote well-being. Interventions to increase psychological capital are assumed to lead to higher efficiency and performance (Luthans and Youssef 2004). The development of hope can be used to build positive well-being through identifying personally important goals, goal design, pathway generation, resources and possible obstacles in achieving goals, reframing barriers, etc. Hope interventions help individuals to set realistic goals that could boost their well-being as they achieve these goals. Optimism is another component of psychological capital development. Optimism can be enhanced through various types of interventions, resulting in increased well-being. Research findings suggest, for example, that gratitude interventions may enhance optimism and well-being (Emmons and McCullough 2003; Froh et al. 2008). Optimistic thinking includes positive expectations for the future and viewing negative life events as temporary, external, and limited to the immediate incident (Seligman et al. 1995). Thus, activities targeting optimistic thinking may prevent teachers from burning out and suffering stress and may have positive effects on their self-efficacy and well-being.

Further practices can be applied in the context of work in order to improve workplace happiness and well-being. Our suggestions are:

-

1.

The use of strengths-based feedback (Roberts et al. 2005; Aguinis et al. 2012; Herman et al. 2012) instead of weakness-focused feedback on performance.

-

2.

Matching of work tasks and employee characteristics using the ‘job crafting’ approach (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001) resulting in work becoming more meaningful for the person, which has a positive effect on well-being and productivity.

-

3.

Using solution-focused brief coaching – this type of coaching focuses on solutions, individual strengths, personal resources, and the future instead of causes and problems. This technique has a positive impact on psychological well-being, strengthens hope and spurs further efforts to achieve the goal (Green et al. 2006; Sherlock-Storey et al. 2013).

Above mentioned research suggest that increasing well-being through intentional activities has multiple effects on employees. Workplace positive psychology interventions are relatively few in number and many previous studies have not focused much on what individuals can do to enhance their own well-being themselves (Sin and Lyubomirsky 2009; Wood et al. 2010; Mazzucchelli et al. 2010). PPIs are simple and time-saving self-guided interventions that can improve well-being in today’s work environment (Meyers et al. 2013).

Our findings seem to be promising in regard to determining main intervention fields for enhancing teachers’ well-being. Considering our main results linked to our research questions, we think that PsyCap can be one of the core constructs of interventions. As our results indicated, all the five well-being factors of PERMA were related to overall PsyCap, and two elements, Positive Emotions and Achievement showed the strongest relationship with it. Our findings also showed that optimism (of PsyCap) and Positive Emotions (of PERMA) were the most relevant factors in relation to overall workplace happiness. Considering these results, on one hand we recommend developing programs aiming at PsyCap components (hope, self-efficacy, resiliency, and optimism) that can have a positive effect on overall well-being (Luthans et al. 2006), and we also suggest putting the main focus on Achievement and Positive Emotions.

Currently little is known about which interventions impact which elements of PERMA but there are a few studies that provide the first results about techniques that increase positive emotions, enhance achievement, and raise global happiness. These studies have used different activities, for example, working on personal goals, committing acts of kindness, visualizing best possible self, or remembering one’s best achievement (Fordyce 1983; Sheldon and Lyubomirsky 2006; Pham and Taylor 1999; Sheldon et al. 2002). In order to design specific and relevant interventions for improving workplace happiness, our qualitative research may help to determine the specific areas and content of them. For example, strengthening the sense of competence and pursuing personal goals can contribute to the sense of success (Sheldon et al.2002) or job crafting technique may help teachers to find or reshape the meaning of their work (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001).

We conclude that the two models of PsyCap and PERMA and our qualitative analysis are a good starting point in developing PPIs in order to improve teachers’ workplace happiness and well-being. An additional future direction could involve developing programs for teachers specifically but more research is needed to work toward recommendations regarding this issue.

Limitations and Future Research

It is important to identify several weaker features of our study. First, our research was conducted based on a sample of Hungarian teachers and therefore the results cannot be generalized to the population. Also, teachers in our sample were affiliated with different types of education institute and we have not controlled for contingency and organizational variables. Another limitation of this research is that the constructs were measured via self-reported questionnaires, and the cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow us to infer causal relationships.

For future directions, it would be interesting to study the level of well-being and happiness among different age (Avanzi et al. 2012; Kinnunen et al. 1994) and occupational groups of teachers or in different educational institutes. We believe that research questions raised in this study deserve further research attention, along with applied PPIs practices in work environment and other relevant constructs that can serve as new resources for workplace well-being and happiness. We hope our results hold implications for the future of positive psychological research for teachers and school settings.

References

Acton, R., & Glasgow, P. (2015). Teacher wellbeing in neoliberal contexts: A review of the literature. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(8).

Aknin, L. B., Barrington-Leigh, C. P., Dunn, E. W., Helliwell, J. F., Burns, J., Biswas-Diener, R., Kemeza, I., Nyende, P., Ashton-James, C. E., & Norton, M. I. (2013a). Prosocial spending and well-being: Cross-cultural evidence for a psychological universal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031578.

Argyle, M. (1987). The psychology of happiness. New York: Methuen.

Avanzi, L., Cortini, M., & Crocetti, E. (2012). When age matters: The role of teacher aging on job identity and organizational citizenship behaviours. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale, 25(3–4), 179–210.

Avey, J. B., Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20070.

Aknin, L. B., Dunn, E. W., Whillans, A. V., Grant, A. M., & Norton, M. I. (2013b). Making a Difference Matters: Impact Unlocks the Emotional Benefits of Prosocial Spending. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 88, 90-95.

Aguinis, H., Gottfredson, R. K., & Joo, H. (2012). Delivering effective performance feedback: The strengths-based approach. Business Horizons, 55(2), 105—111.

Bakker, A. B. (2005). Flow among music teachers and their students: The crossover of peak experiences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 26–44.

Baumann, N. (2012). Autotelic personality. In S. Engeser (Ed.), Advances in flow research (pp. 165–186). New York: Springer.

Benevene, P., Ittan, M. M., & Cortini, M. (2018). Self-esteem and happiness as predictors of school teachers' health: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 9.

Bhatnagar, J., & Biswas, S. (2010). Predictors and outcomes of employee engagement: Implications of the resource-based view perspective. The Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 46(2), 273–288.

Boehm, J. K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Does happiness promote career success? Journal of Career Assessment, 16, 101–116.

Bowling, N. A., Eschleman, K. J., & Wang, Q. (2010). A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between job satisfaction and subjective well-being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X478557.

Bricheno, P., Brown, S., & Lubansky, R. (2009). Teacher wellbeing: A review of the evidence. London: Teacher Support Network.

Briner, R., & Dewberry, C. (2007). Staff wellbeing is key to school success. A research study into the links between staff wellbeing and school performance. London: Worklife Support.

Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (1999). Teacher burnout, perceived self-efficacy in classroom management, and student disruptive behaviour in second-ary education. Curriculum and Teaching, 14(2), 7–26.

Brun, J. P., & Dugas, N. (2008). An analysis of employee recognition: Perspectives on human resources practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190801953723.

Bérdi, M., & Köteles, F. (2010). Az optimizmus mérése: az Életszemlélet Teszt átdolgozott változatának (LOT-R) pszichometriai jellemzõi hazai mintán. Magyar Pszichológiai Szemle, 65(2), 273-294.

Calabrese, R., Hester, M., Friesen, S., & Burkhalter, K. (2010). Using appreciative inquiry to create a sustainable rural school district and community. International Journal of Educational Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513541011031592.

Cameron, K. S., Dutton, J. E., & Quinn, R. E. (Eds.). (2003). Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Chan, D. W. (2009). Orientations to happiness and subjective well-being among chinese prospective and in-service teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 29(2), 139–151.

Chan, D. W. (2010). Gratitude, gratitude intervention and subjective well-being among chinese school teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 30(2), 139–153.

Chida, Y., & Steptoe, A. (2008). Positive psychological well-being and mortality: A quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba.

Connolly, J. J., & Viswesvaran, C. (2000). The role of affectivity in job satisfaction: A metaanalysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 29, 265–281.

Crede, M., Chernyshenko, O. S., Stark, S., Dalal, R. S., & Bashshur, M. R. (2007). Job satisfaction as mediator: An assessment of job satisfaction's position within the nomological network. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317906X136180.

Crosby, F. (1982). Relative deprivation and working women. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Culbertson, S. S., Fullagar, C. J., & Mills, M. J. (2010). Feeling good and doing great: The relationship between psychological capital and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020720.

Dagenais-Desmarais, V., & Savoie, A. (2011). What is psychological well-being, really? A grassroots approach from the organizational sciences. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 659–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9285-3.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-deternination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Deutsch, S., Fejes, E., Kun, Á., & Medvés, D. (2015). A jóllétet meghatározó tényezők vizsgálata egészségügyi szakdolgozók körében. Alkalmazott Psuichológia, 15(2), 49–71.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13, 81–84.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. P. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective wellbeing. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 94–122.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 109–132.

Emmons, R. A. (1986). Personal strivings: An approach to personality and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1058–1068.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389.

Fisher, C. D. (2010). Happiness at work. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(4), 384–412.

Fordyce, M. W. (1983). A program to increase happiness: Further studies. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30, 483–498.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00431.

Freedman, J. (1978). Happy people: What happiness is, who has it, and why. New York: Hartcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Friedman, I. A., & Kass, E. (2002). Teacher self-efficacy: A classroom-organization conceptualization. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 675–686.

Froh, J. J., Sefick, W. J., & Emmons, R. A. (2008). Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 213–233.

George, J. M. (1991). State or trait: Effects of positive mood on prosocial behaviors at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 299–307.

Green, L. S., Osdes, L. G., & Grant, A. M. (2006). Cognitive-behavioral, solution-focused life coaching: Enhancing goal striving, well-being, and hope. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(3), 142–149.

Greller, M. M., Parsons, C. K., & Mitchell, D. R. D. (1992). Additive effects and beyond: Occupational stressors and social buffers in a police organization. In J. C. Quick, L. R. Murphy, & J. J. Hurrell Jr. (Eds.), Stress and well-being at work: Assessments and interventions for occupational mental health (pp. 33–47). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2016.1199294.

Herman, A., Gottfredson, R. K., & Joo, H. (2012). Delivering effective performance feedback: The strengths-based approach. Business Horizons, 55(2), 105–111.

Howell, R. T., Kern, M. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2007). Health benefits: Meta-analytically determining the impact of wellbeing on objective health outcomes. Health Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437190701492486.

Hoy, W. K., & Tarter, C. J. (2011). Positive psychology and educational administration: An optimistic research agenda. Educational Administration Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X10396930.

Holecz, A., & Molnár, S. (2014). Pedagógusok pozitív pszichológiai tükörben: a jóllétet erősítő tényezők jellemzői a pályán. Iskolakultúra, 24(10), 3-14.

Iverson, R. D., Olekalns, M., & Erwin, P. J. (1998). Affectivity, organizational stressors, and absenteeism: A causal model of burnout and its consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1996.1556.

Jayawickreme, E., Forgeard, M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2012). The engine of well-being. Review of General Psychology, 16(4), 327–342.

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693.

Kahn, J., Hessling, R., & Russell, D. (2003). Social support, health, and well-being among the elderly: What is the role of negative affectivity? Personality and Individual Differences. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00135-6.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1103572.

Kinnunen, U., Parkatti, T., & Rasku, A. (1994). Occupational well-being among aging teachers in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 38(3–4), 315–332.

Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254–284.

Kubzansky, L. D., Sparrow, D., Vokonas, P., & Kawachi, I. (2001). Is the glass half empty or half full? A prospective study of optimism and coronary heart disease in the normative aging study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 63, 910–916.

Kun, Á., Gerákné Krasz, K., & Balogh, P. (2017). Development of the work-related well-being questionnaire based on Seligman’s PERMA model. Periodica Polytechnica Social and Management Sciences. https://doi.org/10.3311/PPso.9326.

Kyriacou, C. (2001). Teacher stress: Directions for future research. Educational Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910120033628.

LaMontagne, A. D., Keegel, T., Louie, A. M., Ostry, A., & Landsbergis, P. A. (2007). A systematic review of the job-stress intervention evaluation literature, 1990–2005. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 13(3), 268–280.

LaMontagne, A. D., Martin, A. K., Page, M., Reavley, N. J., Noblet, A. J., Milner, A. J., Keegel, T., & Smith, P. M. (2014). Workplace mental health: Developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-131.

Lavy, S., & Bocker, S. (2018). A path to teacher happiness? A sense of meaning affects teacher-student relationships, which affect job satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(5), 1485–1503.

Layous, K., Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). Positive activities as protective factors against mental health conditions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(1), 3–12.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57, 705–717.

Luthans, F. (2002a). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 695–706.

Luthans, F. (2002b). Positive organizational behavior: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Academy of Management Executive, 16, 57–72.

Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. M. (2004). Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management. Organizational Dynamics, 33, 143–160.

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Norman, S., & Combs, G. (2006). Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-intervention. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 387–393.

Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2007). Psychological capital. New York: Oxford University Press.

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., & Patera, J. L. (2008). Experimental analysis of a web-based intervention to develop positive psychological capital. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 7, 209–221.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46, 137–155.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005a). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005b). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9, 111–131.

Macdonald, D. (1999). Teacher attrition: A review of literature. Teaching and Teacher Education, 15, 835–848.

Meyers, M. C., von Woerkom, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2013). The added value of the positive: A literature review of positive psychology interventions in organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.694689.

Mitchell, R. E., Billings, A. G., & Moos, R. H. (1982). Social support and well-being: Implications for prevention programs. Journal of Primary Prevention, 3, 77–97.

Martos, T., Lakatos, C., & Tóth-Vajna, R. (2014). A Remény Skála magyar változatának (AHS-H) pszichometriai jellemzői. Mentálhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika, 15, 187–202.

Mazzucchelli, T. G., Kane, R. T., & Rees, C. S. (2010). Behavioral activation interventions for well-being: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology 5(2), 105-121.

Nielsen, K., Nielsen, M. B., Ogbonnaya, C., Känsälä, M., Saari, E., & Isaksson, K. (2017). Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1304463.

Page, K. M., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2009). The ‘what’, ‘why’ and ‘how’ of employee well-being: A new model. Social Indicators Research, 90(3), 441–458.

Page, K. M., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2012). From nonmalfeasance to beneficence: Key criteria, approaches, and ethical issues relating to positive employee health and well-being. In N. P. Reilly, M. J. Sirgy, & C. A. Gorman (Eds.), Work and quality of life: Ethical practices in organizations (pp. 463–489). Dordrecht: Springer.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A classification and handbook. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pham, L. B., & Taylor, S. E. (1999). From thought to action: Effects of process- versus outcome-based mental simulations on performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 250–260.

Pratt, M. G., & Ashforth, B. E. (2003). Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 309–327). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Roberts, L. M., Spreitzer, G., Dutton, J., Quinn, R., Heaphy, E., & Barker, B. (2005). How to play to your strengths. Harvard Business Review, 83, 74–80.

Roffey, S. (2012). Pupil wellbeing: Teacher wellbeing. Two sides of the same coin? Educational and Child Psychology, 29(4), 8–17.

Ross, S. W., Romer, N., & Horner, R. H. (2012). Teacher well-being and the implementation of schoolwide positive behavior interventions and supports. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300711413820.

Roysamb, E., Tambs, K., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., Neale, M. C., & Harris, J. R. (2003). Happiness and health: Environmental and genetic contributions to the relationship between subjective well-being, perceived health, and somatic illness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(6), 1136–1146.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 10, 1037110003–066X.55.1.68.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719.

Ramsey, G. (2000). Quality matters. Revitalising teaching: Critical times, critical choices. Sydney: New South Wales Department of Education and Training. Retrieved 12 January 2015, from http://www.det.nsw.edu.au/teachrev/report/

Sansone, C., Sachau, D. A., & Weir, C. (1989). Effects of instruction on intrinsic interest: The importance of context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 819–829.

Segerstrom, S. C. (2007). Stress, energy, and immunity: An ecological view. Current Directions in Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00522.x.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfilment. London: Nicholas Brealey.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Schulman, P. (1986). Explanatory style as a predictor of productivity and quitting among life insurance agents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 832–838.

Seligman, M. E. P., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Thornton, N., & Thornton, K. M. (1990). Explanatory style as a mechanism of disappointing athletic performance. Psychological Science, 1, 143–146.

Seligman, M. E. P., Reivich, K., Jaycox, L., & Gillham, J. (1995). The optimistic child: A proven program to safe-guard children against depression and build lifelong resilience. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60, 410–421.

Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 73–82.

Sherlock-Storey, M., Moss, M., & Timson, S. (2013). Brief coaching for resilience during organisational change – An exploratory study. The Coaching Psychologist, 9(1), 19–26.

Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20593.

Singh, K., & Billingsley, B. (1996). Intent to stay in teaching: Teachers of students with emotional disorders versus other special educators. Remedial and Special Education, 17(1), 37–47.

Smith, C. P. (2000). Content analysis and narrative analysis. In H. T. Reiss & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 313–335). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 249–275.

Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., Yoshinobu, L., Gibb, J., Langelle, C., & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 570–585.

Sonnentag, S. (1996). Work group factors and individual well-being. In M. A. West (Ed.), The handbook of work group psychology (pp. 346–367). Chichester: Wiley.

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., & Thijs, J. T. (2011). Teacher wellbeing: The importance of teacher–student relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 23, 457–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y.

Smith, B. V., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194-200.

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio causal and control beliefs (pp. 35-37).

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063-1078.

Stronge, J. H., Tucker, P.D., & Hindman, J. L. (2004). Handbook for qualities of effective teachers. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria, VA, USA

Sheldon, K. M., Kasser, T., Smith, K., & Share, T., (2002). Personal goals and psychological growth: Testing an intervention to enhance goal attainment and personality integration. Journal of Personality, 70(1), 5-31.

Tadić, M., Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2013). Work happiness among teachers: A day reconstruction study on the role of self-concordance. Journal of School Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.07.002.

Trent, L. M. Y. (1997). Enhancement of the school climate by reducing teacher burnout: Using an invitational approach. Journal of Invitational Theory and Practice, 4(2), 103–114.

Venkataramani, V., Labianca, G. (. J.)., & Grosser, T. (2013). Positive and negative workplace relationships, social satisfaction, and organizational attachment. Journal of Applied Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034090.

Williams, S., & Shiaw, W. T. (1999). Mood and organizational citizenship behavior: The effects of positive affect on employee organizational citizenship behavior intentions. Journal of Psychology, 133, 656–668.

Winefield, A. H., & Tiggemann, M. (1990). Employment status and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.4.455.