Abstract

The paper contains the results of an experimental investigation of fatigue crack development under mixed-mode I + II and I + III in heat-treated 42CrMo4 steel. Tests were performed on heat-treated compact tension shear specimens and rectangular cross-section specimens for mixed-mode I + III. Mixed-mode I + II tests were conducted for 30 and 60° loading angle, while the test for I + III mixed-mode was conducted for 30 and 45°. Additionally, the paper presents fracture analysis results of fatigue crack path development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This study aims to describe fatigue crack growth in 42CrMo4 steel, quenched and tempered to a hardened state. Many machine elements are heat treated to acquire specific mechanical properties of the material (Białobrzeska et al. 2021) and to be used in safety–critical applications. The material studied in this paper is often used for such machine elements that are partially or fully heat-treated and operate under mixed-mode load (Clauß et al. 2020). That was the motivation to conduct an investigation of this particular type of steel. Due to cost-driven economies, structures are designed to retain safety requirements while reducing costs, mainly by mass reduction. Accordingly, modern designs focus on developing structures where crack develops slowly, and the structure can stand its existence rather than create structures with no crack occurrence. Therefore it is essential to investigate crack initiation and growth in materials after the heat-treatment process. Moreover, the knowledge of crack development is fundamental to understand the crack growth redundant mechanism. A significant number of research papers refer to fatigue crack growth for non-complex loading conditions (Beretta et al. 2011; Mohammadi et al. 2021; Lesiuk et al. 2018a)—modes I, II or III—including research on modified due to heat treatment materials. Underline that testing under the mode I condition is well recognized in the standardization process like ASTM E647 standard. However, there is a strong need for an investigation of fatigue crack growth rate under mixed-mode loading condition, which are referring to real operating conditions. Several approaches to that topic were successfully performed in papers that refer to crack growth under mixed mode load (Iriç 2020; Lesiuk et al. 2020a). Nevertheless the subject still requires investigation.

42CrMo4 steel is suitable for quenching and tempering, non-weldable. 42CrMo4 steel is machinable and commonly used for machine elements requiring high strength and ductility, for parts subjected to variable loads, e.g.: axles, crank shafts, gears, discs, rotors, levers and pushers. Usually, aforementioned steel is heat-treated. Nevertheless, according to reported failures, caused by a fatigue crack appearing in the heat-treated zones (Liu et al. 2017; Goto and Nisitani 1994; Hebsur et al. 1980; Wang and Chang 1996; Chen et al. 2017), there arises an open question of how the fatigue crack growth develops in heat strengthened machine elements. The most widely used heat treatment configuration Q + T (quenching and tempering) and fatigue crack propagation, is relatively well described in several papers (Lesiuk et al. 2018a; Escalero et al. 2018; Pandiyarajan et al. 2020; Jing et al. 2021). However, there are few papers devoted to the problem of mixed-mode loading and fatigue crack propagation for 42CrMo4 steel (Heirani and Farhangdoost 2017, 2018).

Therefore, this paper treats on fatigue crack behavior in 42CrMo4 after heat treatment (quenching and low tempering) under mixed mode loading (I + II, I + III), focusing on fatigue crack growth rate curves for this material and loading conditions.

2 Materials and experimental procedures

2.1 Heat treatment

This study's selected heat treatment is most distinctive from a fatigue fracture point of view—quenching and low tempering. The chemical composition (in wt%) of steel used and parameters of applied heat treatment are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

The microstructure of the material after heat treatment is tempered martensite (Fig. 1). In order to acquire the microstructure of the material, the sample was polished and etched with 5% nitric acid solution in methanol. The sample examination was conducted using optical microscopy. As expected, there are visible needle-like grains that are characteristic of martensitic structures. Low tempered martensite is characterized by high hardness and mechanical properties yet low ductility. Tensile strength was determined during static tensile test using round bar samples on the MTS 810 servo-hydraulic test machine. The results of the tensile test are as follows: tensile strength σu = 1547 MPa, yield stress σ0.2 = 1245 MPa material hardness is 45 HRC. Low-temperature tempering is conducted in order to decrease internal stresses after the quenching process.

2.2 Fatigue crack growth test

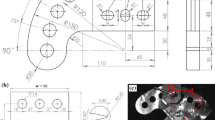

For mode I + II fatigue crack growth rate testing, CTS specimen were used (Fig. 2). Before the experiment, a notch was prepared in the specimen. The notch was 20 mm long and was prepared using electric discharge machining (EDM). At the first stage of the experiment, a pre-cracking process was conducted. All CTS samples were pre-cracked under mode I. Initially, samples were loaded with Fmax = 6.5 kN, stress intensity ratio R = 0.1 and frequency 10 Hz; after 100 000 cycles the load was decreased to Fmax = 4 kN, R = 0.1 and frequency 10 Hz for following 60,000 cycles.

The specimens used for the mixed-mode I + III tests were rectangular in cross-section and 8 mm thick (Fig. 3).

During the second stage, the fatigue test was conducted under mixed-mode I + II for α = 30° and 60°. The specimens were loaded with Fmax = 6 kN, R = 0.1 and frequency 8 Hz. All experiments were conducted on MTS 810 servo-hydraulic test machine. The test stand is presented in Fig. 4. In a specific interval, fatigue crack length was captured using automated imaging DinoLite system.

Fatigue test stand for mode I + II; MTS 810 servo-hydraulic test machine; 1 Control system—MPT software delivered by MTS, 2—Imaging system with DinoLite software for crack length capturing during experiment, 3—load cell, 4—gripping system, 5—CTS specimen holder, 6—DinoLite digital camera, 7—CTS specimen with propagating crack (\(\psi_{0}\) initial crack kinking angle)

Cyclic bending and torsion tests (mode I + III) were performed on the MZGS-100 fatigue machine (Fig. 5) (Lesiuk et al. 2018b; Rozumek et al. 2017, 2020). The tests were performed with a sinusoidal load and an additional mean load (stress ratio R = 0). The specimen placed in the holders (1) and (2) was loaded as a result of vertical movements of the levers, (3) caused by the inertia force of the unbalanced mass on the rotating disk, (4) mounted on flat springs, (5). The mean value of the load was obtained due to the deflection of the spring, (6) of the spring actuator, (7). The development of fatigue cracks was observed with a light microscope, (8) and measured with a micrometer. During the tests, the ratio of the torsional moment to the bending moment was MT/MB = tanα, while the angle α = 30° and 45°.

The tests were carried out with force control (total torque amplitude controlled), under constant amplitude Ma = 17.19 N m with a load frequency of 28.4 Hz. Experimental procedure data is consolidated in Table 3.

3 Results and discussion

The growth of fatigue cracks as a function of the number of cycles for bending with torsion and angle α = 30° and 45° is shown in Fig. 6. Greater durability was observed for specimens tested at an angle α = 45°. A similar case can be observed for fatigue crack growth for mode I + II (Fig. 6), where the greater durability is observed for angle α = 60° than for angle α = 30°.

During the experimental campaign length of the crack, a is measured in terms of the number of cycles and crack path (x and y values of consecutive points on the crack path). However, in describing fatigue crack growth in terms of Paris' Law (Eq. 1), there is a need to calculate the ΔK, which cannot be obtained directly during the experiment (Wang and Chang 1996). Equation 2—ΔK can be determined using mean stress ratio R, an experimental parameter and the stress intensity factor's value.

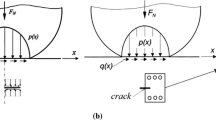

Stress intensity factors are used as constants in equations described field of stress near the crack tip. They are dependent on the geometry of the specimen and the crack. Because crack can be under a different loading mode, stress intensity factors are also independently determined for different modes. In the case of stationary crack, there are often known empirical formulas, which can be used to acquire stress intensity factors (SIFs). The Williams formula can also be used for Compact Tension Shear specimen (Eqs. 3 and 4) (Paris and Erdogan 1963; Sih 1974; Richard 1981; Lesiuk et al. 2020b). Where symbols are denoted as follows: F—loading force, a0—length of the notch with pre-crack, α—loading force angle, W—specimen width.

However, the formulas mentioned above are only valid when the crack propagation increment length is zero. For the non-zero crack propagation length, there are no empirical formulas. Thus, these values must be obtained using numerical methods, for example finite element method. All analysis was conducted within the Simulia Abaqus 6.14 environment. A two-dimensional model was used. The geometry of the specimen reflects the experimental specimen. To recreate mixed-mode loading under mode I and mode II, special boundary conditions are used. Forces V1, V2, H (Fig. 7) are calculated in this way, that their sum is equal to the force generated on the experimental stand (6 kN or 10 kN) and the direction of the force is 30 or 60°. These boundary conditions are presented below in Fig. 7. Used Eqs. 4 to 7 are presented below too (b and c are geometrical parameters of the specimen and the alpha is the angle of force action). Force is transferred to the model by kinematic coupling between the reference points and the edges of the holes.

Stress intensity factors were obtained using an integral contour approach. The crack tip nodes of the finite element mesh were translated by a quarter of the element's length (as a result, the crack tip is modelled by 3-nodes linear plane stress elements). The rest of the model 4-nodes bilinear plane stress quadrilateral elements with reduced integration and hourglass control were used. The actual crack is modelled as seam (no connection between two surfaces split by seam). Results were obtained in 10 contours and then calculated in contours between 6 and 10 to avoid singularity effects in the first contours. A schematic view of the crack tip area is presented in Fig. 8.

It is worth mentioning that it was required for every crack path point to perform independent simulations. Overall, dozens of simulations must be conducted to obtain all needed in further analysis data. Obtained results are presented in Fig. 9.

For both loading angle cases, it is noticeable that a more significant impact on crack development has mode I. Nevertheless, with an increase of the loading angle, mode II's influence on crack development increases.

Similarly, the da/dN—∆K diagrams were constructed for mode I + III using closed-form formulas for stress intensity factors. The ranges of the stress intensity factor for mode I and mode III were calculated using equations (Harris 1967; Chell and Girvan 1978):

where Δσ—stress range, a0—notch length, a—crack length.

The Y correction factors were calculated from the equations given in the literature (Harris 1967; Chell and Girvan 1978).

Comparing the experimental results in Fig. 10 shows that the change in angle α from 30 to 45° increases the ΔK value for modes I and III. We can also observe slightly higher crack growth rates for 45°. For angle 30°, higher values of ΔK are observed for mode I, while for 45° we see the mixing of modes I and III.

Figure 11 shows the experimental results for mixed-mode I + II and I + III. Comparing results for mode I + II, it is noticeable that fatigue crack growth rate for loading angle α = 60° is significantly higher than the crack growth rate for the lower loading angle. Comparing the test results for mixed-mode I + III, one can notice higher fatigue crack growth rates for the angle α = 45°, compared to the angle α = 30°. Moreover, for the angle α = 45° in the second and third stages of the velocity curve, slight increases in these velocities can be noticed, compared to the observed results for α = 30°.

The test results for the fatigue crack growth rate versus the stress intensity factor range, shown in Fig. 11 has been obtained from the Huber-Mises criterion for proportional loading:

4 Fatigue crack paths analysis

According to the maximum tangential stress criterion (MTS) the initial kinking angle of crack must satisfy the following equation (Erdogan and Sih 1963):

and finally, allow determining the initial angle of crack initation (kinking) angle:

The development of the crack for mixed mode I + II is shown in Fig. 12. In both cases, the crack path did not deviate from the theoretical crack path respectively for each loading angle. For loading angle of 30° the crack initiation angle was approximately 27.5°, while for loading 60° the crack initiation angle was approximately 47.6°. Experimentally determined initial crack angles for mode I + II are plotted in Fig. 13 and compared with the MTS prediction.

The development of the crack paths for mixed-mode I + III is shown in Fig. 14. Various shapes of cracks as they grow and develop at different angles can be observed. When bending with torsion at 30°, the crack paths increased at the angle α1 = 10–15°, while at the angle of 45°, the paths increased at the angle α1 = 21° and 28°.

Detailed fractography study is shown in Figs. 15, 16, 17, 18. Fractograms of the fracture surface obtained from mode I + II and loading angle of 30 degrees are presented in Fig. 15. It is observed the brittle nature of fatigue crack with visible numerous intergranular areas (IG)—Fig. 15a—and secondary cracks typical for mode I. Due to relatively low mixity level, fracture mechanism for 2 mm long fatigue crack under mixed mode loading condition is mostly characterized by typical fatigue fracture with numerous intergranular regions. As the fatigue crack growths, the increase of KI/KII ratio causes the dominant fracture mechanism to be similar to mode I pre-crack mechanism (Fig. 15c vs a). Due to KI increasing with the crack length increase, the fracture surface is characterized by numerous secondary cracks—Fig. 15d.

Fatigue fracture surface for mixed-mode I + II loading condition under load angle α = 60°, a mode I precrack region, a enlarged precrack region, c 6 mm crack length, da/dN = 7·10–5 mm/cycle, d enlarged part of fracture surface presented in c, e 11 mm crack length, da/dN = 3.65·10–4 mm/cycle, f enlarged part of fracture surface presented in e

As the loading angle increases, the initial KI/KII ratio increases, and the primary fracture mechanism is slightly different (Fig. 16) than for loading angle 30° (Fig. 15). The same fracture mechanism is observed for the mode I pre-crack region (Fig. 16a–b). However, for 6 mm, crack lengths are visible flat regions caused by shear mode—Fig. 16c–d. With the increase in the crack length (Fig. 16e–f) dominant mode I fatigue crack growth is observed by occurrence of numerous intergranular regions.

For mixed-mode I + III (Figs. 17, 18), fracture surface was mostly shaped by shear mode fatigue crack growth with numbers of "flat" areas damaged by complex deformation mechanisms. Figure 17a–b presents the initial fatigue crack path obtained for mode I + III loading and the angle of 30°. Additionally, noticeable is a mixed type of fracture—transgranular and intergranular—Fig. 17b.

With increased mixity constraints, under load angle 45° (mode I + III), dominant transgranular fatigue crack growth is observable in the initial stage of fatigue crack growth (Fig. 18a–b). As the crack grows, the mode I fatigue crack growth mechanism is dominant (Fig. 18c–d) with a typical fracture surface for a complex stress-state.

5 Conclusions

The results of fatigue crack growth tests on notched specimens made of 42CrMo4 steel in the hardened state, all tested under mixed-mode I + II and I + III loading conditions, help draw the following conclusions:

-

1.

According to the mode I + II, the fatigue crack growth for the crack inclination angles α = 30° and 60°, was observed only in the initial stage of cracking up to 1–2 mm. After this KI mode was dominant.

-

2.

For mixed-mode I + II each time, the value of the parameter ΔK for mode I was higher than mode II.

-

3.

Fatigue lifetime increases with loading angle for both modes I + II and I + III.

-

4.

For mixed-mode I + III and load angle 45° similar crack growth rates for mode I and mode III were observed. On the other hand, the parameter ΔK) had higher values for mode III, and mode I dominated as the crack increased.

-

5.

Fatigue crack paths obtained for mode I + II follow MTS criterion in terms of the initial crack angle.

-

6.

Based on Huber-Mises criterion—ΔKeq does not consolidate all modes into one line—which is usually expected. This observation is valid for mixed modes I + II and I + III.

References

Beretta S, Foletti S, Valiullin K (2011) Fatigue strength for small shallow defects/cracks in torsion. Int J Fract 33:287–299

Białobrzeska B, Jasiński R, Konat L, Szczepański L (2021) Analysis of the properties of hardox extreme steel and possibilities of its applications in machinery. Metals 11(1):1–19

Chell GG, Girvan E (1978) An experimental technique for fast fracture testing in mixed mode. Int J Fract 14:81–84

Chen W, Chen H, Li C, Wang X, Cai Q (2017) Microstructure and fatigue crack growth of EA4T steel in laser cladding remanufacturing. Eng Fail Anal 79:120–129

Clauß B, Schaller S, Schubert A (2020) Investigations of non-circular turning using a high-acceleration drive unit based on aerostatic bearing principle. In: Proceedings of the 20th international conference of the European Society for Precision Engineering and Nanotechnology, EUSPEN 2020, pp 385–388

Erdogan F, Sih GC (1963) On the crack extension in plates under plane loading and transverse shear. J Basic Eng ASME Trans 85:519–525

Escalero M, Blasón S, Zabala H, Torca I, Urresti I, Muniz-Calvente M, Fernández-Canteli A (2018) Study of alternatives and experimental validation for predictions of hole-edge fatigue crack growth in 42CrMo4 steel. Eng Struct 176:621–631

Goto M, Nisitani H (1994) Fatigue life prediction of heat-treated carbon steels and low alloy steels based on a small crack growth law. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct 17(2):171–185

Harris DO (1967) Stress intensity factors for hollow circumferentially notched round bars. J Basic Eng 89:49–54

Hebsur MG, Abraham KP, Prasad YVRK (1980) Effect of electroslag refining on the fracture toughness and fatigue crack propagation rates in heat treated AISI 4340 steel. Eng Fract Mech 13(4):851–864

Heirani H, Farhangdoost K (2017) Mixed mode I/II fatigue crack growth under tensile or compressive far-field loading. Mater Res Express 4(11):116505

Heirani H, Farhangdoost K (2018) Effect of compressive mode I on the mixed mode I/II fatigue crack growth rate of 42CrMo4. J Mater Eng Perform 27(1):138–146

Iriç S (2020) Experimental and numerical investigations of crack growth under mixed-mode loading. Emerg Mater Res 9(4):1319–1324

Jing JN, Dong LH, Wang HD, Jin G (2021) Influences of vacuum ion-nitriding on bending fatigue behaviors of 42CrMo4 steel: Experiment verification, numerical analysis and statistical approach. Int J Fatigue 145:106104

Lesiuk G, Duda MM, Correia J, de Jesus AMP, Calcada R (2018a) Fatigue crack growth of 42CrMo4 and 41Cr4 steels under different heat treatment conditions. Int J Struct Integr 9(3):1–9

Lesiuk G, Szata M, Rozumek D, Marciniak Z, Correia J, De Jesus A (2018b) Energy response of S355 and 41Cr4 steel during fatigue crack growth process. J Strain Anal Eng Des 53(8):663–675. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309324718798234

Lesiuk G, Smolnicki M, Rozumek D, Krechkovska H, Student O, Correia J, Mech R, De Jesus A (2020a) Study of the fatigue crack growth in long-term operated mild steel under mixed-mode (I + II, I + III) loading conditions. Materials 13(1):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13010160

Lesiuk G, Smolnicki M, Mech R et al (2020b) Analysis of fatigue crack growth under mixed mode (I + II) loading conditions in rail steel using CTS specimen. Eng Fail Anal 109:104354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2019.104354

Liu F, Lin X, Yang H, Wen X, Li Q, Liu F, Huang W (2017) Effect of microstructure on the fatigue crack growth behavior of laser solid formed 300M steel. Mater Sci Eng A 695:258–264

Mohammadi R, Najafabadi MA, Saghafi H, Saeedifar M, Zarouchas D (2021) The effect of mode II fatigue crack growth rate on the fractographic features of CFRP composite laminates: An acoustic emission and scanning electron microscopy analysis. Eng Fract Mech 241:107408

Pandiyarajan R, Arumugam K, Prabakaran MP (2020) Fatigue life and fatigue crack growth rate analysis of high strength low alloy steel (42CrMo4). Mater Today 37:1957–1962

Paris P, Erdogan F (1963) A critical analysis of crack propagation laws. J Fluids Eng Trans ASME Doi 10(1115/1):3656900

Richard HA (1981) A new compact shear specimen. Int J Fract. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00033347

Rozumek D, Marciniak Z, Lesiuk G, Correia JAFO (2017) Mixed mode I/II/III fatigue crack growth in S355 steel. Proc Struct Integr 5:896–903

Rozumek D, Lewandowski J, Lesiuk G, Correia J (2020) The influence of heat treatment on the behavior of fatigue crack growth in welded joints made of S355 under bending loading. Int J Fatigue. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2019.105328

Sih GC (1974) Strain-energy-density factor applied to mixed mode crack problems. Int J Fract 10:305–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00035493

Wang CC, Chang Y (1996) Effect of postweld treatment on the fatigue crack growth rate of electron-beam-welded AISI 4130 steel. Metall Mater Trans A 27(10):3162–3169

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Grant Number 2018/31/N/ST8/03590 financed by the Polish National Science Centre (Narodowe Centrum Nauki, NCN).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duda, M., Rozumek, D., Lesiuk, G. et al. Fatigue crack growth under mixed-mode I + II and I + III in heat treated 42CrMo4 steel. Int J Fract 234, 235–248 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10704-021-00585-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10704-021-00585-0