Abstract

Differences in feeding performance and aggressive abilities between species and sexes of hummingbirds are often associated with the partitioning of their food sources, but whether such partitioning results in floral isolation (reproductive isolation at the stage of pollination) has received little attention. We examined components of floral isolation and pollinator effectiveness of Heliconia caribaea and H. bihai on the island of Dominica, West Indies. The short flowers of H. caribaea match the short bills of male Anthracothorax jugularis, its primary pollinator, whereas the long flowers of H. bihai match the long bills of female A. jugularis, its primary pollinator. In pollination experiments, both sexes of A. jugularis were equally effective at pollinating the short flowers of H. caribaea, which they preferred to H. bihai, whereas females were more effective at pollinating the long flowers of H. bihai. Moreover, an average difference in length of 12 mm between H. caribaea and H. bihai flowers did not prevent heterospecific pollen transfer, and both sexes transported pollen between the two plant species. In field studies using powdered dyes as pollen analogs, however, heterospecific pollen transfer was minimal, with only 2 of 168 flowers receiving dye from the other species. The length of H. bihai flowers acted as an exploitation barrier to male A. jugularis, which were unable to completely remove nectar from 88% of the flowers they visited. In contrast, interference competition combined with high floral fidelity through traplining prevented female A. jugularis from transferring pollen between the two Heliconia species. A combination of exploitation barriers, interference and exploitative competition, and pollinator preferences maintains floral isolation between these heliconias, and may have contributed to the evolution of this hummingbird-plant system.

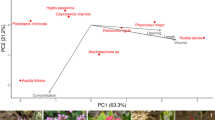

a–d Modified from Temeles and Kress (2003)

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Arizmendi MC, Ornelas JF (1990) Hummingbirds and their floral resources in a tropical dry forest in Mexico. Biotropica 22:172–180

Bateman AJ (1951) The taxonomic discrimination of bees. Heredity 5:271–278

Berry F, Kress WJ (1991) Heliconia: an identification guide. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC

Cotton PA (1998) Coevolution in an Amazonian hummingbird-plant community. Ibis 140:639–646

Cuevas E, Espino J, Marques I (2018) Reproductive isolation between Salvia elegans and S. fulgens, two-hummingbird-pollinated sympatric species. Plant Biol 20:1075–1082

Darwin C (1862) On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilized by insects. John Murray, London

Fairbairn DJ, Reeve JP (2001) Natural selection. In: Fox CW, Roff DA, Fairbairn DJ (eds) Evolutionary ecology: concepts and case studies. Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, pp 35–54

Feinsinger P (1976) Organization of a tropical guild of nectarivorous birds. Ecol Monogr 46:257–291

Feinsinger P, Colwell RK (1978) Community organization among neotropical nectar-feeding birds. Am Zool 18:779–795

Fenster CB, Armbruster WS, Wilson P, Dudash MR, Thomson JD (2004) Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 35:375–403

Foellmer MW, Fairbairn DJ (2005) Competing dwarf males: sexual selection in an orb-weaving spider. J Evol Biol 18:629–641

Fulton M, Hodges SA (1999) Floral isolation between Aquilegia formosa and Aquilegia pubescens. Proc R Soc Lond B 266:2247–2252

Gill FB, Wolf LL (1975) Economics of feeding territoriality in the golden-winged sunbird. Ecology 56:333–345

Gowda V, Kress WJ (2013) A geographic mosaic of plant-pollinator interactions in the Eastern Caribbean islands. Biotropica 45:224–235

Gowda V, Temeles EJ, Kress WJ (2012) Territory fidelity to nectar sources by purple-throated caribs, Eulampis jugularis. Wilson J Ornithol 124:81–86

Grant V (1949) Pollination systems as isolating mechanisms. Evolution 3:92–97

Grant V (1992) Floral isolation between ornithophilous and sphingophilous species of Ipomopsis and Aquilegia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:11828–11831

Grant V (1994) Modes and origins of mechanical and ethological isolation in angiosperms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:3–10

Grant KA, Grant V (1968) Hummingbirds and their flowers. Columbia University Press, New York

Grant V, Temeles EJ (1992) Foraging ability of rufous hummingbirds on hummingbird flowers and hawkmoth flowers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:9400–9404

Iles WJD, Sass C, Lagomarsino L, Benson-Martin G, Driscoll C, Specht CD (2017) The phylogeny of Heliconia (Heliconiaceae) and the evolution of floral presentation. Mol Phylogen Evol 117:150–167

Kay KM (2006) Reproductive isolation between two closely related hummingbird-pollinated neotropical gingers. Evolution 60:538–552

Kearns CA, Inouye DW (1983) Techniques for pollination biologists. University Press of Colorado, Niwot, CO

Kress WJ, Betancur J, Echeverry B (1999) Heliconias—Llamaradas de la selva Colombiana. Cristina Uribe Editores, Bogotá, Colombia

Lande R, Arnold SJ (1983) The measurement of selection on correlated characters. Evolution 37:1210–1226

Maglianesi MA, Böhning-Gaese K, Schleuning M (2015) Different foraging preferences of hummingbirds on artificial and natural flowers reveal mechanisms structuring plant-pollinator interactions. J Anim Ecol 84:655–664

Nattero J, Sérsic AN, Cocucci AA (2010) Patterns of contemporary phenotypic selection and flower integration in the hummingbird-pollinated Nicotiana glauca between populations with different flower-pollinator combinations. Oikos 119:852–863

Queiroz JA, Quirino ZGM, Machado IC (2015) Floral traits driving reproductive isolation of two co-flowering taxa that share vertebrate pollinators. AoB Plants 7:plv127

Rodríguez-Gironés MA, Santamaría L (2004) Why are so many bird flowers red? PLoS Biol 2(10):e350

Rodríguez-Gironés MA, Santamaría L (2005) Resource partitioning among flower visitors and evolution of nectar concealment in multi-species communities. Proc R Soc Lond B 272:187–192

Rodríguez-Gironés MA, Santamaría L (2006) Models of optimal foraging and resource partitioning: deep corollas for long tongues. Behav Ecol 17:905–910

Rodríguez-Gironés MA, Santamaría L (2007) Resource competition, character displacement, and the evolution of deep corolla tubes. Am Nat 170:455–464

Rodríguez-Gironés MA, Santamaría L (2010) How foraging behaviour and resource partitioning can drive the evolution of flowers and the structure of pollination networks. Open Ecol J 3:1–11

Rodríguez-Gironés MA, Sun S, Santamaría L (2015) Passive partner choice through exploitation barriers. Evol Ecol 29:323–340

Santamaría L, Rodríguez-Gironés MA (2015) Are flowers red in teeth and claw? Exploitation barriers and the antagonistic nature of mutualisms. Evol Ecol 29:311–322

Scheistl FP, Schlüter PM (2009) Floral isolation, specialized pollination, and pollinator behavior in orchids. Annu Rev Entomol 54:425–446

Shaw JP, Taylor SJ, Dobson MC, Martin NH (2017) Pollinator isolation in Louisiana iris: legitimacy and pollen transfer. Evol Ecol Res 18:429–441

Snow DW, Snow BK (1980) Relationships between hummingbirds and flowers in the Andes of Colombia. Bull Br Mus Nat Hist 38:105–139

Stiles FG (1975) Ecology, flowering phenology and hummingbird pollination of some Costa Rican Heliconia species. Ecology 56:285–301

Taylor J, White SA (2007) Observations of hummingbird feeding behavior at flowers of Heliconia beckneri and H. tortuosa in southern Costa Rica. Ornithol Neotrop 18:133–138

Temeles EJ, Kress WJ (2003) Adaptation in a plant-hummingbird association. Science 300:630–633

Temeles EJ, Kress WJ (2010) Mate choice and mate competition by a tropical hummingbird at a floral resource. Proc R Soc Lond B 277:1607–1613

Temeles EJ, Pan IL (2002) Effect of nectar robbery on phase duration, nectar volume, and pollination in a protandrous plant. Int J Plant Sci 163:803–808

Temeles EJ, Rankin AG (2000) Effect of the lower lip on pollen removal by hummingbirds. Can J Bot 78:1164–1168

Temeles EJ, Pan IL, Brennan JL, Horwitt JN (2000) Evidence for ecological causation of sexual dimorphism in a hummingbird. Science 289:441–443

Temeles EJ, Linhart YB, Masonjones M, Masonjones HD (2002) The role of flower width in hummingbird bill length—flower length relationships. Biotropica 34:68–80

Temeles EJ, Goldman RS, Kudla AU (2005) Foraging and territory economics of sexually-dimorphic purple-throated caribs, Eulampis jugularis, at three heliconias. Auk 122:187–204

Temeles EJ, Shaw KC, Kudla AU, Sander SE (2006) Traplining by purple-throated carib hummingbirds: behavioral responses to competition and nectar availability. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 61:163–172

Temeles EJ, Koulouris CR, Sander SE, Kress WJ (2009) Effect of flower shape and size on foraging performance and trade-offs in a tropical hummingbird. Ecology 90:1147–1161

Temeles EJ, Rah YJ, Andicoechea J, Byanova KL, Giller GSJ, Stolk SB, Kress WJ (2013) Pollinator-mediated selection in a specialized hummingbird-Heliconia system in the Eastern Caribbean. J Evol Biol 26:347–356

Temeles EJ, Newman JT, Newman JH, Cho SY, Mazzotta AR, Kress WJ (2016) Pollinator competition as a driver of floral divergence: an experimental test. PLoS ONE 11:e0146431

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Andre, S. Durand, and M. Burton of the Forestry Service of the Commonwealth of Dominica and M. Thomas for assistance and support, S. and A. Peyner-Loehner for accommodations and hospitality, N. J. Horton for statistical advice, and M. A. Rodríguez-Gironés, M. Symonds, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by an Amherst College Faculty Research Award and an Amherst College Senior Sabbatical Fellowship through The H. Axel Schupf ‘57 Fund for Intellectual Life, NSF Grant DEB-1353783, and the Chinese Scholarship Council. Our experimental protocol for the capture, care, and experimental work on hummingbirds adhered to IACUC guidelines and was reviewed and approved by the Forestry Department of the Commonwealth of Dominica and by the IACUC Committee of Amherst College.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Temeles, E.J., Liang, J., Levy, M.C. et al. Floral isolation and pollination in two hummingbird-pollinated plants: the roles of exploitation barriers and pollinator competition. Evol Ecol 33, 481–497 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-019-09992-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-019-09992-1