Abstract

Natural wetlands are critically important to the lives and livelihoods of many people. Human activities result in the degradation of wetlands globally, and more so in developing countries prioritizing fast economic growth and development. With an increasing population in their immediate surroundings, wetlands in Wakiso District, Uganda, have become over-exploited to meet human needs. Policies, plans and projects have been put in place aiming at wetland conservation and restoration, but with limited stakeholder participation, have achieved limited success. Our research objective was to identify stakeholders, their perceptions, and understand the role these perceptions play in wetland conservation and restoration activities. To achieve these objectives, we used the ecosystem services concept within a qualitative, multi-site case study research approach. Findings show that stakeholders hold divergent perceptions on wetland ecosystem services, perceiving them as source of materials, fertile places for farming, cheap to buy and own, as well as being “God-given”. Furthermore, wetlands as habitats are perceived as not prioritized by central government. Implications for conservation and restoration vary with stakeholders advocating for (1) over-use, wise-use or not-use of wetlands and their resources, (2) educating and sensitization as well as (3) the implementation of the available laws and policies. This paper explores the findings and important implications for the conservation and restoration of wetlands in Wakiso District, Uganda.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Natural wetlands are among the most biodiverse ecosystems on earth, the most productive environments and vital for human survival (Xu et al., 2020). In article 1.1 of the Ramsar Convention, wetlands are defined as “areas of marsh, fen, peat, or water whether natural or artificial, permanent, or temporary with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish, or salty including areas of marine water, the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six metres” (Ramsar Convention Secretariat, 2005, page 1). In Uganda, wetlands are defined as areas permanently or seasonally flooded by water, with plants and animals specifically adapted to this environment (National Environment Act, 2019). Wetlands are integral to supporting the achievement of the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) through contributing to clean water and sanitation (SDG 6)and life on land (SDG 15) (Kakuba & Kanyamurwa, 2021).

The ecosystem services obtained and provided by wetlands support the well-being and survival of many communities through the provisioning of water, food and construction materials (Namaalwa et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2020). Papyrus swamps comprise the highest percentage of inland wetlands in East Africa (Namaalwa et al., 2013; Ministry of Water and Environment (MWE), 2016, 2019). Over the years, papyrus wetlands have been subjected to drainage in favour of agriculture (Schuyt, 2005); over-harvesting (Kakuru et al., 2013; Mengesha, 2017; Wamala, 2021; Zhang, 2019) through ineffective management (Hartter & Ryan, 2010); destruction by large mammals (Morrison et al., 2012); and the effects of climate change. Wetlands are generator areas of life as many species reproduce, spread and populate other locations from there (Zsuffa et al., 2016). The importance of wetlands as outlined justifies the call and need for their conservation and restoration in Uganda and elsewhere in the world.

Uganda is experiencing a high level of inland wetland conversion and degradation. According to the Ministry of Water and Environment (2019), the wetland area reduced from 15% in 1994 to less than 9% by 2018. The same is happening on a global scale (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), 2005; UNFCCC, 2018; Pueyo-Ros et al., 2019; Chanda, 1996; Choudri et al., 2016; Meyer, 2018). About 35% of the global wetland is reported to be lost since the 1970 (Ramsar Convention, 2018). Humans in their pursuit to improve agricultural production and industrialization have for many decades converted wetlands to other uses (Sandhu & Sandhu, 2014), leading to their degradation. There is a strong human nature interdependence (Constanza et al., 1997; De Groot et al., 2012; McInnes, 2013; MEA 2005; Zhao et al., 2016) and development as we know it affects and depends on natural ecosystems such as wetlands (Ranganathan et al., 2008).

Many factors explain why wetland areas are shrinking in Uganda including population increase, rural to urban migration, informal settlements, agricultural activities, poverty, animal grazing, industrialization and other infrastructural developments. The wetlands around Lake Victoria where this study was carried out have been subjected to high levels of conversion. For example, between the years 2008–2014, 53.8% of the wetlands were lost (Government of Uganda, 2016) and the conversion is perceived to be increasing to date. Since 1995, Uganda has put in place several laws and guidelines to help and support conservation and restoration of wetlands with negligible success partly because the implementation of such laws lacks backing and support from government. The government is in a dilemma as it wants to develop and create wealth for the citizens through conversion of natural resources yet at the same time it is mandated to ensure the wise-use of such resources. With more people struggling with poverty, it is quite challenging today and in the foreseeable future to conserve wetlands in Uganda unless alternative sources of livelihoods are put in place and equally accessed by the citizens. Indeed, Mafabi (2018) observed that in many communities of Uganda, wetlands cannot be conserved without other economically viable livelihood options, incentives and benefits given to those that depend on the wetland. Thus, finding options for their survival for those that entirely depend on wetlands as well as those who use them for business is a challenge for the government.

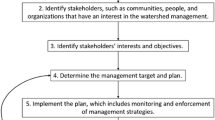

There are many calls to conserve and restore the world wetlands (Simaika et al., 2021; Ministry of Water and Environment, 2019). Conservation and restoration of wetlands necessitate the intervention, collaboration and participation of many stakeholders. The importance of stakeholder involvement in conservation has been emphasized (Dick et al., 2018; Sowińska-Świerkosz & García, 2021; Ramsar Convention Secretariat, 2010). When stakeholders from various disciplines and sectors are involved in the planning and implementation of a wetland conservation project, it raises awareness and appreciation of the intervention (Dick et al., 2018) and thereby favours sustainable wetland management (Bosma et al., 2017). Also, it enables policy makers to base their decisions on local knowledges and the felt needs of those that are affected and benefit from such policies (Grimble & Chan, 1995; Hopkins et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2015). Stakeholders are characterized by divergent degrees of influence and importance when it comes to making decisions regarding wetland conservation and restoration in their respective areas of work (Namaalwa et al., 2013) and such power is exhibited when there is an engagement in differing phases of designing, planning, implementing, monitoring and maintaining a given conservation project (Zingraff-Hamed et al., 2020). Failure to involve stakeholders in wetland conservation presents the possibility of non-cooperation or outright opposition (Grimble & Chan, 1995), thus increasing the probability of failure to conserve and restore wetlands.

A wealth of existing research points to the fact that to achieve success in conservation, wetland management should involve the most concerned stakeholders (DeCaro & Stokes, 2008; Miller & Montalto, 2019; Omoding et al., 2020). In addition, deliberate efforts are required to create awareness aimed at changing popular negative perceptions associated with wetlands to realize their sustainability. Different perceptions and attitudes create unique relations with the environment, and local priorities and tradeoffs are embedded therein (Curșeu & Schruijer, 2017; Miller & Montalto, 2019). Stakeholder inclusion and active participation in ecosystem management interventions has been elaborated by many scholars (Ambrose-Oji et al., 2017; Ruiz-Frau et al., 2018; Spangenberg et al., 2015). In Uganda, there are several interventions geared towards wetland conservation and restoration, but available literature points to their failure (Isunju et al., 2016; Kalanzi, 2015; Mafabi, 2018), and one of the reasons is inadequate stakeholder participation (Nakiyemba et al., 2020). In the research reported here, we focus on understanding and explaining the role human perceptions play in influencing their actions in wetland conservation and restoration. We place particular emphasis on stakeholders at the community level by looking at two separate wetlands in Uganda, one recognized as of international importance (Ramsar site), and the other, a small and locally managed wetland. We wanted to find out whether community-level stakeholder perceptions are indeed included or considered when designing or implementing policies and interventions aimed at wetland conservation.

Conceptually, the study adopted the ecosystem services framework. Ecosystem services are the benefits humans obtain from ecosystems (Costanza et al., 1997; de Groot et al., 2002a, 2002b; MEA 2005; Sandhu et al., 2012; Wratten, 2013). Studies on ecosystem services have focused on the benefits that people derive from the wetland ecosystem (Barakagira & de Wit, 2019; Bikangaga et al., 2007; Constanza, 2000; Costanza et al., 2014; Finlayson, 2015; Horwitz et al., 2012). According to Asah et al (2014), the focus on benefits has led to a limited understanding of how values for wetlands as ecosystems are shaped by the way stakeholders perceive, depend and use them. According to MEA (2005), there are four categories of ecosystem services, namely provisioning, regulating, cultural and supporting. Several ecosystem services are obtained and provided by Lutembe and Nabaziza wetlands including provisioning (provision of water (drinking, construction and irrigation), provision of raw materials (sand, clay, papyrus, grass for thatching), herbs, clean air, firewood, grazing land for animals, farming grounds for (rice, yams, vegetables), fish, hunting and source of income through selling of fish and agricultural produce. Regulating services include reducing water runoff, soil erosion, flood control and mitigation, water storage, purification and weather regulation. There are also cultural/nonmaterial benefits such as tourism, leisure, birdwatching, venue for cultural practices especially those of spiritual nature, place for education and research. Finally, supporting services are necessary to produce other services such as soil formation, soil fertility, habitat for wildlife, breeding areas for fish and other terrestrial and aquatic species.

We investigated the nature and role of stakeholder perceptions on the restoration and conservation of Lutembe Bay and Nabaziza wetlands in Wakiso. The assumption was that if majority of stakeholders appreciated the values and benefits obtained from wetlands, they would want to participate in, and support their conservation. As proposed by Gosling et al (2017), Dlamini et al. (2020) and Sinthumule (2021), successful wetland conservation and management requires a positive mind and willingness to participate across stakeholder groups including those at community level. We build on a growing body of work on stakeholders perceptions on wetland ecosystems (e.g. Ainscough et al., 2019; McNally et al., 2016) and wetland functioning (Bosma et al., 2017). There are, however, limited studies that have specifically focused on the role played by stakeholder perceptions in influencing actions towards wetland conservation in Wakiso District. It is not yet clear as to why with all the knowledge about climate change and its effects, resources invested in the conservation and restoration of natural resources by national and international organizations as well as the studies done globally the conversion of wetlands continues at an increasing rate. Thus, this study sought to fill that gap through identifying, documenting and analysing perceptions stakeholders have on wetland ecosystem services and their effect on conservation and restoration related activities.

2 Study area

Wakiso District Local Government (DLG) is in Central Uganda and part of the greater Kampala Metropolitan Area. The district has 2807.75 km2 of the land of which 384 km2 are wetlands and by 2016 this comprised of slightly over 13% of its land covered by wetlands. Unfortunately, there have been consistent and increasing reports of the disappearance of wetlands in the district due to developments that are taking place (Kariuki et al., 2016; Tumusiime, 2013; Wakiso, 2017). In Wakiso, there are two wetlands of international importance (Lutembe Bay and Mabamba wetlands). Given its geographical location, Wakiso District is experiencing a high rate of urbanization with a diversity of population in terms of social and economic class, level of education, employment status, different cultures and tribes that live and work there (Wakiso, 2017). There are also many upcoming commercial farms growing flowers, vegetables or fish farming, targeted to benefit from the ready market available in the communities and district because of the high population.

Wetlands in Wakiso District play a significant role in sheltering Lake Victoria by cleansing the water runoff from Kampala and the neighbouring districts. Lake Victoria is locally known as Nalubaale and is the world’s second-largest freshwater lake and the largest in Africa. The lake shares boarders with Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. It is the only source of fresh water for both domestic and industrial use in Kampala city, Wakiso, Mukono and Mpigi districts and other surrounding areas. According to Tumuhimbise (2017), most of the permanent wetlands in Wakiso District are found in Entebbe Municipality and Busiro County along the shores of Lake Victoria. With the ever-increasing rural to urban migration in the country, coupled with the ever-rising cost of living in Kampala and surrounding areas, many of the people who have migrated to the city from other areas of Uganda find it easy and relatively affordable to live in Wakiso, where the cost of living is still considered relatively low compared to living in Kampala city. Undoubtedly, this increases the pressure on the available resources in the district and calls for proper planning, including how to conserve the remaining natural wetlands (Muwanguzi, 2018).

Lutembe Bay is a lacustrine type of wetland as per the Ramsar Convention Secretariat classification. It covers the areas of Katabi, Kajjansi and Makindye Ssabagabo Town Councils of Wakiso District. It is along the Kampala–Entebbe International Airport highway (00°10ʹ N 32°34ʹ E), just twenty-five kilometres away from the capital Kampala. The study stakeholders were from Kajjansi Town Council in the communities of Lutembe Ddewe, Bwerenga and Nganjo. According to data from Uganda Bureau of Statistic (UBOS), Kajjansi Town Council has a population of 135,600 (UBOS, 2021). The wetland was declared a Ramsar site by the government of Uganda in 2006 as an Important Bird Area (Arinaitwe et al., 2010). It is a wetland of international importance and a major tourist attraction. Local tourists come to the area for leisure especially during weekends.

All organisations and groups focused on aspects of wetland conservation or restoration combine under one local umbrella organisation known as the Lutembe Wetland Users Association (LWUA).

Nabaziza wetland site is in Kyengera Town Council, Wakiso District, along the Kampala—Masaka Highway connecting Uganda to Tanzania and Rwanda. It is one of the small wetlands in Uganda that are rarely included in surveys or maps but undergoing conversion. Kyengera Town Council has a population of 285,400 (UBOS, 2021). Nabaziza wetland on the side of Kyengera covers the villages of Nkokonjeru B, Nabaziza and Masanda. The wetland is a tributary of river Mayanja and forms part of the Mayanja Wetland System (Basudde, 2013). As evidenced in Fig. 1a, the wetland is in a highly urbanizing suburb of Kampala City, and this partly explains the challenges it is facing such as illegal dumping of wastes, high levels of encroachment by those constructing informal settlements, crop farmers, clay brick making and the proposed Kampala–Mpigi express Highway which is to pass through the wetland.

The two wetlands are located in the same district and have similarities and differences in terms of their characteristics that are likely to impact on the efforts regarding their conservation and restoration. Lutembe Bay being in a fast-urbanizing community is exposed to many challenges related to its conversion as it is part of Lake Victoria which attracts many people to come in either as fishermongers, traders or residents who buy big plots and establish homes or small encroachers that occupy sections of the wetland illegally waiting for their eviction (Table 1).

3 Materials and methods

Following a qualitative multi-site case study research design (Creswell, 2013), fieldwork was conducted over a 6-month period by the first author in two areas within Wakiso District. Qualitative data were collected using semistructured interviews. Guided by Bryman (2016), the research questions focused on enabling stakeholders to describe their perceptions and feelings and establish their reasoning behind what individuals do in relation to wetland conservation. Drawing on common characteristics of the case study design (Zainal, 2007), we engaged with communities to explore and investigate the contemporary real-life phenomenon of wetland loss, degradation and possibilities for conservation and restoration.

3.1 Study participants

Overall, forty stakeholders were engaged in this study with ten participants from each of the following categories: Lutembe Bay community, Nabaziza wetland community, Wakiso District and National level. Twenty stakeholders were selected at the community level representing a diverse group of people that largely derive their living by working in and around the wetland. These included (1) Water fetchers, (2) Crop and animal farmers, (3) Sand and clay miners, (4) Beach management unit (BMU) a unit that established by government to oversee activities that take place on the beach and report to government accordingly, (5) Herbalists, (6) Tour guides, (7) Representatives of community-based organizations focusing on wetland conservation, (8) Local leaders, (9) Religious leader representatives and (10) Handicraft association representatives. From each of the above categories, one member represented the group. Lutembe Wetland Users Association was helpful in locating the members, and the selection was done purposively given the sensitivity of the study. Ten participants were selected at district level including district technical leaders (district natural resources officer, environment officers, wetland officer, community development officer, organizations and a religious leader). At national level, participants were from Ministry of Water and Environment, research institutions, media and civil society including national and international organizations (Table 2).

3.2 Data management and analysis

Primary data were collected through interviews, then transcribed and translated to English when the local language was used. The transcripts were then processed and analysed following steps. All interviews were audio recorded on a digital recorder, transcribed and typed in Microsoft Word. Data familiarization was achieved through reading the transcripts and identifying the major themes. The themes identified were then coded through marking key ideas, phrases and concepts in the transcripts. A code as defined by Clarke and Braun (2017) is the smallest unit of analysis that captures interesting features of data relevant to the research question. Then, the transcribed interviews were entered into NVivo 12 Pro software for sorting and easy identification. In NVivo, individual transcripts were organized in several nodes, and from them, some verbatim statements were identified from the coded transcripts which were later incorporated in this paper. Therefore, NVivo was used to organize data and filter it for ease of access based on the generated thematic codes and nodes. Analysis of the data was done using the embedded analysis as suggested by Creswell (2013). Interpretation was done through identifying links, meanings, differences from quotes, nodes and themes to draw answers to the research question. Finally, we used embedded analysis (Creswell, 2013) where we looked at aspects of stakeholder perceptions in relation to several factors of interest such as wetland ownership, wetland use, current and future state of wetland, benefits derived from wetlands as well as perceptions that stakeholders had on wetlands and their implications for conservation and restoration efforts.

3.3 Limitations to the study

Efforts to include representatives from the manufacturing sector (industries and factories) as well as large flower farms were unsuccessful. Despite numerous attempts, none agreed to be interviewed. Representatives from Environmental police were also inaccessible despite initial agreements. We cannot confirm why these stakeholders refused to be interviewed but can hypothesize that it relates to the presence of negative publicity about both large-scale industry and governance in the recent past, especially regarding their role in wetland degradation. Interviews at district and national levels were conducted digitally via telephone as they were conducted at a time when Uganda was under lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Face-to-face interactions were missed along with their associated benefits of observing non-verbal cues that accompany the respondents’ responses.

4 Results of the study

4.1 Stakeholder perceptions of wetlands

Stakeholders had various perceptions on Lutembe and Nabaziza wetlands. Some were similar, complementary, or overlapping, yet others were different. Our findings show that human perceptions are very complex to understand given their heterogeneous nature. What is constant is that different stakeholder perceptions affect the way they interpret the ecosystem services that are provided by the wetlands. There were a few stakeholders who perceived wetlands as places that deserved total protection, restricting all activities, while others looked at them as a source of materials for their livelihoods. To those who perceived them as a source of materials, restricting access to the wetland meant changing their livelihoods altogether. In turn, this would negatively affect their social, cultural and economic well-being. As shown in Table 3, the primary reasons stakeholders had for relating with the wetland were highly influenced by their livelihoods.

The key perceptions that emerged after data analysis were related to the following aspects of the wetland ecosystem and had significant impacts on the actions or inactions that later the stakeholders engaged in, in as far as wetland conservation and restoration is concerned.

4.2 Wetlands as a source of materials

Community-level stakeholders perceive wetlands as a source of livelihood in the form of Mudfish and Lungfish for eating or selling. Other materials provided include papyrus for weaving, water for domestic use and sand and clay for house construction. Stakeholders, especially those who were older, regarded wetlands as a source of medicinal plants and herbs for treating some human ailments such as skin and stomach related diseases as well as snake bites. This was not common among the young stakeholders, and it could be because of changes in the community with the advance of modern medicine. These activities have a direct effect on the status and functioning of the wetland and is related to the scale of the extraction. For instance, when substantial amounts of papyrus and other vegetation are cut down to create space for farming, the level of degradation of the wetland can be severe. Whereas some of the activities are on a small scale such as sand and clay mining, many were found to be on a large scale, especially farming. The larger the scale, the higher the perceived impact on the state of the wetland, and its actual impact cannot easily be estimated in the short term. Whereas stakeholders at the community level were more familiar with the direct values that they obtained from the wetland, there were other indirect values that are related to functions and services such as environment protection, water purification, water storage and any other services and these were highlighted by those at district level.

4.3 Wetlands as fertile lands for crop and animal farming

Stakeholders involved in growing crops perceived wetlands as fertile lands suitable for crops. Indeed, many community members were engaged in the growing of crops especially vegetables in and around wetlands. People have been growing crops along the wetland edges for many years. What has changed now is that some people are moving into the wetland, away from the edges, clearing and burning the papyrus, degrading the wetland. Other people ferry and pour soil picked from the dry land to areas that are wet to be able to grow their crops. Earlier studies such as Kakuru et al (2013) noted that around 80% of the people who live near wetlands in Uganda derive their livelihood from it. The major crops grown include yams, cassava, cabbages, tomatoes, sweet potatoes and other vegetables. One of the study participants at the community level stated that, “… this wetland [Lutembe] does so many things for us. We grow food there, get grass for our animals and some have started fish farming”. Such an observation suggests that the respondent attaches a lot of importance to the existence of the wetland since through human action, wetlands support the generation of many types of provisioning services albeit contributing to their degradation. Whereas many people still depend on the wetland for their food, Mbabazi et al. (2010) discourage such practices. In their study, they cautioned people to refrain from eating crops grown in wetlands due to the high threat of ingesting heavy metals that accumulate in the wetlands following heavy rainfall events (Fig. 2).

Wetlands are perceived to be immensely helpful during dry seasons for the cattle keepers as they would remain green and provide grass that can be eaten by the animals. Certainly, the participants at the community level did not perceive animal grazing to be one of the degrading activities among those done in the wetland. The reason was that whatever the cattle fed on would grow again rapidly and thus it was not a reason to worry about. The fact that agriculture and animal grazing are not perceived as detrimental to the functioning of wetlands in Wakiso District is in agreement with observations from Musasa and Marambanyika (2020) who noted that cultivation and livestock grazing are the dominant wetland use activities in Zimbabwe.

4.4 Wetlands offer cheap and affordable options to the poor to access land

Over half of the study participants were of the view that lands in or around wetlands were cheaper compared to dry lands. There were also people who simply came and occupied parts of a wetland without paying any fee or rent, content to stay until evicted by government officials. There are some insights that the encroachers know that what they were doing was illegal and against the set laws that govern wetlands. Nevertheless, due to life challenges they end up encroaching the wetland in search for survival even when they know that it will be temporary. The search for survival partly explains why a wetland like Lutembe Bay is occupied by so many people owning or using small plots of land.

4.5 Wetlands as “God-given” and belonging to no one

Community stakeholders perceive wetlands as “God-given” and therefore belonging to no one. In contrast, stakeholders at district and national levels perceive wetlands as belonging to individuals and institutions. There is evidence of lack of consensus regarding ownership of wetlands in the district. To many stakeholders, the wetlands belong to no one and are managed by the government on behalf of citizens. Yet, the government and business sector continue to commodify wetlands by fencing off sections and preventing community members from access. This deprives the people access to essential resources such as water. Ownership of wetland as private property is highly contested and often the cause of conflict especially when the public have been prohibited from accessing and using wetland resources which they perceive to belong to no one. Lack of clear ownership has made wetland conservation in the district to be a concern of everybody, but a responsibility of no one. Participants argued that one cannot ably manage what does not belong to them.

In a bid to streamline issues of wetland ownership and management, the central Uganda government designated three categories of wetlands that are managed at distinct levels: (1) wetlands of international importance (Ramsar sites); (2) national importance (critical wetlands); and (3) local importance (valuable wetlands) as outlined in the National Environmental Act (MWE, 2019). In the Act, the central government is mandated to manage only the first two categories, and the third one valuable wetlands are managed at community level. The “wise-use” of wetlands is only acceptable in Uganda by law to apply to those wetlands categorized as critical and valuable and not in the wetlands of international importance. The practice in Wakiso District shows no different treatment whether a wetland is of national importance, critical or valuable. They are all degraded and continually converted to pave way for other developments. The practice of parcelling plots in Lutembe wetland and issuance of titles were of particularly great concern for many stakeholders at both the community and district levels. As stated by one stakeholder at the community level “The dilemma we have while trying to conserve our wetlands are those who even up to-today are still issuing land/ plot titles on the wetland”. It was indeed noted that if all individuals owning plots of land on Lutembe wetland decided to use them, there will be no wetland vegetation left. This in a way deflates the efforts and zeal of those involved in wetland conservation and restoration efforts.

4.6 Central government perceived as not prioritizing wetland conservation

Wetlands are perceived to be one of the ecosystems that are not prioritized by the central government. There is a cross-cutting perception among stakeholders especially at the community and district levels. The central government and its environment protection agencies are perceived to be not doing enough to streamline the management of wetlands in Wakiso District. Participants alleged that a few officials in government do facilitate and supervise the encroachment on wetlands through issuing permits, land and plot titles in wetlands. With extensive structures already in place, the government is perceived and indeed believed to have the capacity and means to conserve wetland if there was political will. “… we know that the government institutions in place have the capacity to protect the wetland if those in power chose to do so. But they chose to ignore it” mentioned a stakeholder at the national level. Another participant doubted the possibility of the government officials to conserve the wetland stating that much of the degradation is associated with the government: “Degradation of wetlands is largely by the government itself; it is either by people who are working for the government, their accomplices or a project supported by government or a government project such as establishment of a road or factory”. As Hobfoll et al., (2018) observed that individuals and groups strive to obtain, retain, foster and protect the resources they value. It would appear here some government officials do not value wetlands as an ecosystem. It can be argued that the central government is more concerned with development and meeting economic gains (Ondiek et al., 2020) from the wetlands rather than caring about the other values and benefits derived from them.

4.7 Wetlands as places of spiritual practices

Both Lutembe and Nabaziza were perceived as sources of spiritual power. Hence both wetlands are visited by many people, not only those who lived near them but also from distant places. The visitors come to consult the spirits believed to be found in the wetlands. Seeking for spirits and blessings from wetlands supports Russi’s (2013) statement that there are social and cultural values to the wetlands. Local knowledge has it that the name Lutembe originated from a practice of calling a Crocodile from Lake Victoria to give them blessings (Stakeholder at the community level). Nabaziza wetland is a tributary of River Mayanja which is full of traditions in the central region as it is widely believed to have been birthed by a Muganda woman named Nalongo. To date, some people go to the river and use its banks as a spiritual and historical place (Basudde, 2013). In addition to spiritual blessings, both Lutembe and Nabaziza are perceived as rich sources of traditional herbs that help people in treating some skin infections, stomach pains, snake bites, cough and chest pains. While talking about the relevance of the wetland, one participant commented: “As a Herbalist I do get herbs from Lutembe wetland. I used to get many herbs in the past from the wetland, but they are now reducing as people clear the wetland vegetation to plant their crops or graze animals”. Because of large vegetation cutting and burning to establish gardens, many of the varieties of herbs in the form of grass, roots, trees and flowers can no longer be found. As confirmed by Ondiek et al (2020), such disappearance reduces the value of the wetlands a source of materials and spiritual centres.

4.8 Wetlands as tourist attractions

Lutembe wetland is widely known as an International Birding Area. The migration of birds such as White-winged Terns, Gull-billed Terns from Europe between September and March attract tourists, specifically those interested in birdwatching. There are concerns that the wetland and its ability to host birds that tourists want to see is under threat. As one of the study participants commented: “I am worried because what tourists used to come for is no longer present. The birds like the Shoebill were everywhere, today you can take hours to find one”. The changes that are happening in Lutembe are real and felt by the local stakeholders and many are just left wondering what is happening. Such scenarios could point to either migration or extinction of some wildlife that used to inhabit the wetland.

Nabaziza wetland also attracts visitors that come to learn about the wetland including students from nearby primary and secondary schools. There are also community members who walk along the wetland edge as a form of leisure especially during the evening hours. Community members visit the wetland to relax and get connected with nature.

4.9 Wetlands as degraded ecosystem

Wetlands were on a whole perceived as degraded in Wakiso District. It was one of the most agreed upon perceptions by more than half of the stakeholders. Wetlands are perceived to be reducing in size, quality and vegetation cover as most of their edges are converted to other uses. Examples include, construction of houses, growing crops, animal farms, flower gardens, factories as well as other businesses like establishment of petrol stations. While describing their perceptions regarding the state of wetlands in Wakiso District, some stakeholders used phrases such as “it is worrying”, “wetlands are threatened extensively”, “it is alarming”, “it is appalling” and “wetland coverage is reducing”. One stakeholder at the district level noted that “The state of wetlands in the district is worrying because there is a lot of degradation. We cannot say that the status is the same as we started it is on a decline trend because of several reasons”. Another participant from the community level explained that “… previously all the wetland [Lutembe Bay] was covered by forest and it could rain a lot in this area. Now, rainfall has become so unpredictable and that has led to changes in our seasons”. After the trees were cut down, the land was divided into small plots and sold to numerous people. The stated quotes suggest that stakeholders perceive wetlands as being encroached on at a high scale portraying a bleak future if no action is taken to avert the situation.

5 Discussion

The results have highlighted several ecosystem services that people obtain from wetlands and presented arguments for the need for conservation of what is remaining of the wetlands as well as restoration of what has already been converted to other uses. Clearly, the central government has done a lot to enact laws but has not created an enabling environment for the implementation of the same laws to allow for success in wetland conservation and restoration. Perhaps, the biggest conundrum is for the government to balance the need and drive for wealth creation while at the same time conserving natural resources such as wetlands. All this happens in a country where there is increase in population and demand for land for other uses as it is the case with other developing countries (Asumadu et al., 2023). There is need for many local-level studies to support evidence-based wetland management practices which this study contributes to. Consequently, the study adds to the body of knowledge about perceptions stakeholders have on wetland ecosystem conservation and restoration in Wakiso District, Uganda. The research contributes to the current discussion on how to increase chances of success in efforts geared towards nature conservation particularly wetlands in developing countries.

There are three broad implications of stakeholder perceptions regarding wetland conservation and restoration. These perceptions may lead to over-use, wise-use and not-use of wetlands and their resources. Stakeholders who are more inclined to and or supported the uncontrolled conversion of wetlands to meet human and developmental needs lead to actions that results in increased conversion, degradation and over-use of wetland resources. Those whose perceptions supported wise-use of wetlands appreciate the dangers resulting from over-use and are concerned that uncontrolled conversion would lead to disaster. Wise-use of wetland resources is recommended in a number of studies including Keddy and Fraser, (2000), Kalanzi, (2015), Gupta et al., (2020), Kingsford et al., (2021) and the Ramsar Convention Secretariat (2010). Wise-use is defined as the maintenance of the wetland’s ecological character achieved through the implementation of ecosystem approaches (Finlayson et al., 2015; Gardner & Davidson, 2011). The third and final group were those stakeholders whose perceptions were against using wetlands at all and wished to leave them intact, arguing that a lot of degradation and conversion has already taken place. These were in support of large scale conservation and restoration programmes as well as ensuring that what remains should not tampered with at all costs.

Many stakeholders that participated in this study support wise-use because they reason that humans have for decades relied on the services offered or supported by wetlands. This agrees with what Warbington and Boyce, (2023) and Gosling et al., (2017) observed that communities living adjacent to the wetland know their value but may end up over-using them in the absence of regulation and enforcement. Some stakeholders were deeply concerned about the continued conversion of wetlands and called for immediate conservation and restoration if future generations are to benefit from wetlands. Stakeholders with this perception are most likely not to engage in actions that would further degrade the wetland. Some stakeholders at the community level did not only guard the wetlands but also discouraged others from degrading them. Sensitizing others on the relevance of conserving and restoring wetlands was done emphasizing the benefits, goods and services they provided. Unfortunately, these were the minority among the study participants and comprised about 30% of the study population.

As the results show, there has been a failure in clearly understanding and using this concept in the two wetlands of Lutembe and Nabaziza. The same results could be applied to other wetlands in the Wakiso District and the central region at large. Wetlands around Lake Victoria tend to face almost similar challenges such as over-use especially the harvesting of papyrus and encroachment for agricultural production. Failure to promote and adopt the “wise-use” concept could be as a result of lack of capacity to implement the required practices as outlined by the Ramsar Secretariat recommendations (Ramsar Convention Secretariat, Handbook I, 2010; Ostrovskaya et al., 2013), or a lack of knowledge about the wetland and its usefulness (Gardner & Davidson, 2011). Evidence from interviews shows that local-level stakeholders consider what they do as wise-use since they have done so for ages given that their wetland has the capacity to regenerate. It is new practices such as back filling and flower farming which completely alters the ecological character and state of the wetland.

There are stakeholders that perceived wetland as a source of livelihoods materials, as fertile land for crop and animal farming, cheap and affordable, “God-given”, and not being prioritized by the central government. These perceptions are a danger to the existence of wetlands in the district because they contribute to over-use, conversion and degradation of wetlands. The need for present survival as opposed to future is largely the driving force. It is natural for some people to always think about their own needs or those of their immediate family members first before considering the larger society. Whereas such stakeholders may not be completely stopped from accessing such resources depending on the established norm, they need to be assisted to find alternative livelihoods if they are to co-exist with such a fragile ecosystem. Therefore, stakeholders with these perceptions need to be identified, involved and made aware of how their perceptions and actions negatively affect the overall functioning of the wetland ecosystem. There is need for constant reminders that natural resources such as wetlands in most countries belong to the living, the dead and the yet to be born.

The perception that wetlands are “God-given” makes it difficult to exercise caution believing that it does not harm individual members of the community, yet that endangers other creatures and species that live in the wetlands. No wonder there has been a reported decline in the number of fish species caught from Lake Victoria which is partially attributed to loss of wetlands and climatic change. In response to the reduced quantities of fish, the government has deployed soldiers to monitor fishing activities on the lake and to reduce the use of illegal fishing nets locally known as “Kambamajji”, “Bungulu” and “Kokota” and unauthorized fishing boats called “Baotaddu” or “Paala”. Those who use illegal fishing nets and boats are perceived to make more money since they catch small fish which they sell and earn more than those who use authorized gear. The continued degradation of especially Lutembe Bay wetland where fish produces from as it lays there eggs contributes significantly to the persistent loss of fish and low catch affecting hundreds of people that depend on that trade.

The study found that stakeholders had varied perception regarding who is responsible for conserving and restoring wetlands in Wakiso District. Those named include government, civil society organizations, community members as the key institutions responsible for conserving wetlands. Surprisingly only one stakeholder said, “it was the responsibility of everyone to manage the wetland”. Notably, participants at the community level mentioned civil society as not only responsible for conservation and restoration of wetlands but also as owners. A possible explanation for this could be that civil society organizations are possibly the most active in the field but also engage and involve local people in their programme activities related to wetland conservation. The benefits of stakeholder participation have been expressed by many scholars (Bal et al., 2013; Centre & Jeffery, n.d.; Nakiyemba et al., 2020; Pluchinotta et al., 2018). The more stakeholders participate, the higher the possibilities of arriving at an effective management, especially when it comes to natural resources.

Perceiving wetlands as very fertile lands with water has always attracted many low-income earners to settle on them. After they fail to get alternative land elsewhere to construct houses and grow some crops to feed themselves that is when some turn to wetlands. When all the edges are all safeguarded by their perceived owners, such wetland users’ resort to going deep inside the wetland to establish their own sections where no one claims ownership. Whereas wetlands should be conserved, maintained or rehabilitated (Turyasingura et al., 2023), this study found that more and more farmers are entering deep into the wetland to grow vegetables especially in Lutembe Bay. This affects the essential role of the wetland in climate change mitigation since especially flower farmers are cutting, burning, backfilling large sections of the wetland to establish gardens hence changes the ecological character of the wetland. Moomaw et al. (2018) stress the need for wetlands to be protected from direct human disturbance as this affects their functioning and contradicts the wise-use principle.

The perception that some central government officials, ministries and departments do not prioritize wetland conservation was prevalent even when there were many presidential directives calling on wetland encroachers to vacate. The central government in general was perceived as the leading contributor to wetland conversion in Wakiso District, yet it bears the highest responsibility to conserve wetlands. This is a challenge that is cutting across many African countries where even when there is remarkable progress in developing policies for wetland conservation (Simaika et al., 2021) there exist implementation challenges. Although the majority stakeholders in this study (57%) said it was the responsibility of government to conserve wetlands, 13% of the stakeholders are not aware of who is exactly responsible (see details in Fig. 3). The perceived inadequate prioritization means that not enough funds are allocated to monitor and prevent wetland encroachment. It also demotivates staff leaving them helpless to act even when they want to. Continuous allocation of wetland sections to private developers clearly shows a lack of commitment to conserve and restore wetlands in the district.

There is a sense of despondency among some district level stakeholders. For example, one of the stakeholders stated that, “Do you want me to be shot at first for you to know I care about wetland conservation?”, and another asked “Should I use my private car and fuel it to do government work?” Such could be interpreted as lack of morale for the staff to do what they ought to do. Then statements indicate that some government employees in wetlands management are becoming less hopeful about the success of their efforts, and thus are resigned to doing the little they can. Inadequate support demoralizes staff at district and Town Council level and inhibits their ability to monitor and conduct detailed and up-to-date inventories on what is remaining of the wetland, despite that being a prerequisite for proper planning (Simaika et al., 2021). Hence, it paves the way for individual wetland degraders to continue unchallenges at the expense of the majority stakeholders who are meant to benefit from such resources whether directly or indirectly.

The perceived absence of political will in wetland conservation makes the available policies less effective. Considering what is on the ground, the available laws ought to be amended to cater for the current crisis where the district is about to lose all the natural wetlands. The same observation was arrived at in a study by Ostrovskaya et al. (2013), that wetland management capacities are high at policy formulation level but extremely weak at implementation level. Therefore, availability of good laws and policies not backed by political will and enforcement commitment from the side of government is not sufficient to bring about the desired increment in wetland restoration.

Issues of survival may in many cases supersede the need to conserve wetlands. The challenge is to ensure that people escape poverty, while at the same time conserving and/or restoring Wakiso natural wetlands. In line with Agol et al. (2021), our study demonstrates that there is a great urgency to manage, conserve and restore wetland ecosystems in Wakiso District. However, as Verhoeven (2014) observes even with the protection of wetlands by laws they are still converted to other uses especially where major economic and social interests are at stake. Therefore, there is a conundrum that calls for more research to support survival and decent life, while at the same time conserving the environment.

“The good thing with the current generation is that majority of the people are educated and now the responsibility is with you. Whatever happens it is your responsibility. It is sad that your [referring to the interviewer] generation seem not to care about the environment, and it is being destroyed as you look on. It is really sad!” Interview Community level stakeholder.

There is an emerging perception that wetlands are vanishing because Wakiso District is increasingly urbanizing. Urbanization was referred to commonly by district level stakeholders who argue that many people want to live in the district because the price of land is still lower compared to the capital Kampala. Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 4, urbanization was only the fourth driver of wetland conversion following increase in poverty, population increase and crop and animal farming as the major drivers of wetland conversion in Wakiso District. However, such an argument can be challenged because urbanization per se is not a threat to wetland survival in the region, but rather what allows urbanization to take place such as wetlands not being clearly demarcated, ownership challenges, not being politically prioritized by central government makes wetlands disappear is the main concern. As evidenced by the study results, addressing unplanned urbanization, informal settlements, over exploitation of wetland resources reducing destructive farming practices like the use of herbicides and pesticides will enable stakeholders to conserve and restore wetlands amidst pressures of urbanization. However, as Eroğlu & Erbil (2022) observe, it is a challenge to manage many stakeholders with varied expectations for a long time. Managing expectations call for constant reviews and updates to ensure that stakeholder interests are always at the forefront of any wetland conservation project.

Introducing and adopting contemporary designs of housing infrastructure can help in creating more space for social and economic activities. With the current scattered settlement patterns, it makes it hard to distribute social services such as water and electricity to everyone. On the contrary, when people live in specific defined places, it creates space for more farming activities as well as conservation of the forests and wetlands. At the time of this study, firewood and charcoal were the main source of energy for cooking in the district. Enabling people to adopt the use of improved energy sources, like electricity for cooking and lighting, can go a long way in boosting the wetland conservation effort. In a study about cost of cooking technologies in Uganda, it was found that using gas was the cheapest form of fuel, followed by electricity, then charcoal and firewood (Black et al., 2021). The argument is that making the cost of accessing and using electricity affordable to most of the households will save the country hundreds of hectares of natural forests and aid the conservation of wetlands.

There have been continuous presidential directives and statements calling upon all those who encroached on the wetland illegally to leave. It may be said that these have been ignored and not implemented by those to whom they are directed. The government is expected to observe and promote the right of nature as stated in the Environment Act of 2019 that “Nature has the right to exist, persist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycles, structure, functions and its processes in evolution” (MWE, 2019, page 18). It is categorically clear that wetlands, as part of nature, also have a right to be conserved and restored where damage has been done to them either through human action or any other reason. It can be argued that effective participation and involvement of all concerned stakeholders is key to attain success in wetland conservation and restoration. The benefits of stakeholder participation have been expressed by many scholars (Centre & Jeffery, 2009; Pluchinotta et al., 2018).

6 Conclusion

The study was set out to establish the stakeholder perceptions on wetland conservation and restoration activities in Wakiso District, Uganda. This research has shown that there are many stakeholders involved in wetland conservation and restoration and that they have varied perceptions, motivations and interests for their participation and operate at various levels with community level stakeholders being the least active ones. Second major finding was that no single stakeholder category is responsible for the degradation and conversion of wetlands although the degree and scale of their contribution differs with commercial farmers contributing more than for example papyrus harvesters. Results further showed that the central government even when it has put in place enabling laws and policies to help guide conservation and restoration of wetlands, its agencies have not been in position to successfully implement them hence leaving the management of this critical resource in the hands of those who want to use it to benefit self rather than societal needs. Most of the stakeholders supported wise-use in principle but lacked capacity to implement it. Taken together, these results suggest that majority of the stakeholders are concerned about the current state of wetland degradation in Wakiso District and blamed the central government for not doing enough to halt the practice using the available laws and policies. However, driven by the desire to create wealth and improve the standards of living for majority citizens, it is likely to remain a big challenge for the government to conserve wetlands as it strives to develop the country. Every effort needs to be taken to address this socio-ecological and development challenge that faces Wakiso District and Uganda at large to achieve balanced and sustainable development.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Agol, D., Reid, H., Crick, F., & Wendo, H. (2021). Ecosystem-based adaptation in Lake Victoria Basin; synergies and tradeoffs. Royal Society Open Science, 8(6), 201847. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.201847.

Ainscough, J., de Vries Lentsch, A., Metzger, M., Rounsevell, M., Schröter, M., Delbaere, B., de Groot, R., & Staes, J. (2019). Navigating pluralism: Understanding perceptions of the ecosystem services concept. Ecosystem Services, 36, 100892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.01.004.

Ambrose-Oji, B., Buijs, A., Ger Hoházi, E., Mattijssen, T., Száraz, L., van der Jagt, A. P. N., Hansen, R., Rall, E., Andersson, E., & Kronenberg, J. (2017). Innovative governance for urban green infrastructure: A guide for practitioners. In Work Package 6: Innovative Governance for Urban Green Infrastructure Planning and Implementation GREEN SURGE Deliverable 6.3. Green Surge.

Arinaitwe, J., Byaruhanga, A., & Mafabi, P. (2010). Key sites for the conservation of waterbirds in Uganda. OSTRICH. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00306525.2000.9639882.

Asah, S. T., Guerry, A. D., Blahana, D. J., & Lawler, J. J. (2014). Perceptions, acquisition and use of ecosystem services: Human behaviour, and ecosystem and policy implications. Ecosystem Services, 10, 180–186.

Asumadu, G., Quaigrain, R., Owusu-Manu, D., Edwards, D. J., Oduro-Ofori, E., Kukah, A. S. K., & Nsafoah, S. K. (2023). Analysis of risks factors associated with construction projects in urban wetlands ecosystem. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 30(2), 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2022.2130465.

Barakagira, A., & de Wit, A. H. (2019). The role of wetland management agencies within the local community in the conservation of wetlands in Uganda. Environmental & Socio-Economic Studies, 7(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.2478/environ-2019-0006.

Basudde, E. (2013). The Mystical River Mayanja. Retrieved 25 Jan 2020 from https://www.newvision.co.ug/news/1322489/mystical-river-mayanja.

Bikangaga, S., Picchi, M. P., Focardi, S., & Rossi, C. (2007). Perceived benefits of littoral wetlands in Uganda: A focus on the Nabugabo wetlands. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 15(6), 529–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-007-9049-3.

Black, M. J., Roy, A., Twinomunuji, E., Kemausuor, F., Oduro, R., Leach, M., Sadhukhan, J., & Murphy, R. (2021). Bottled Biogas—An Opportunity for Clean Cooking in Ghana and Uganda. Energies, 14(13), 3856. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14133856.

Bosma, C., Glenk, K., & Novo, P. (2017). How do individuals and groups perceive wetland functioning? Fuzzy cognitive mapping of wetland perceptions in Uganda. Land Use Policy, 60, 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.10.010.

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

Centre, D., & Jeffery, N. (2009). Stakeholder Engagement: A Road Map to Meaningful Engagement. 48.

Chanda, R. (1996). Human perceptions of environmental degradation in a part of the Kalahari ecosystem. Geo Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00174930.

Choudri, B. S., Baawain, M., Al-Sidairi, A., Al-Nadabi, H., & Al-Zeidi, K. (2016). Perception, knowledge and attitude towards environmental issues and management among residents of Al-Suwaiq Wilayat, Sultanate of Oman. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 23(5), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2015.1136857.

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613.

Costanza, R. (2000). Social goals and the valuation of ecosystem services. Ecosystems, 3, 4–10.

Costanza, R., de Groot, R., Sutton, P., van der Ploeg, S., Anderson, S. J., Kubiszewski, I., Stephen Farber, R., & Turner, K. (2014). Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change, 26, 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.002.

Costanza, R., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., O’Neill, R. V., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R. G., & Sutton, P. (1997). The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature, 387, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

Curșeu, P. L., & Schruijer, S. G. (2017). Stakeholder diversity and the comprehensiveness of sustainability decisions: The role of collaboration and conflict. Current Opinion in Environment Sustainability, 28, 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.09.007

de Groot, R., Brander, L., van der Ploeg, S., Costanza, R., Bernard, F., Braat, L., Christie, M., Crossman, N., Ghermandi, A., Hein, L., Hussain, S., Kumar, P., McVittie, A., Portela, R., Rodriguez, L. C., ten Brink, P., & van Beukering, P. (2012). Global estimates of the value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units. Ecosystem Services, 1(1), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2012.07.005.

De Groot, R. S., Mathew, A. W., & Boumans, R. (2002b). A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Journal of Ecological Economics, 41(3), 393–408.

De Groot, R. S., Wilson, M. A., & Boumans, R. M. J. (2002a). A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecological Economics, 41(3), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00089-7.

DeCaro, D., & Stokes, M. (2008). Social-psychological principles of community-based conservation and conservancy motivation: Attaining goals within an autonomy-supportive environment. Conservation Biology, 22(6), 1443–1451. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00996.x.

Dick, J., Turkelboom, F., Woods, H., et al. (2018). Stakeholders’ perspectives on the operationalization of the ecosystem service concept: Results from 27 case studies. Ecosystem Services, 29, 552–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.09.015.

Dlamini, S., Tesfamichael, S. G., Shiferaw, Y., & Mokhele, T. (2020). Determinants of environmental perceptions and attitudes in a socio-demographically diverse urban setup: The case of Gauteng Province, South Africa. Sustainability, 12(9), 3613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093613.

Eroğlu, M., & Erbil, A. Ö. (2022). Appraising science-policy interfaces in local climate change policymaking: Revealing policymakers’ insights from Izmir Development Agency, Turkey. Environmental Science & Policy, 127, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.09.022.

Finlayson, C., M. (editor) (2015). Wetlands and human health. Journal of wetland: Ecology, Conservation and Management Serie No.5.

Gardner, R. C., & Davidson, N. C. (2011). The Ramsar Convention. In B. A. LePage (Ed.), Wetlands (pp. 189–203). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0551-7_11.

Gosling, A., Shackleton, C. M., & Gambiza, J. (2017). Community-based natural resource use and management of Bigodi Wetland Sanctuary, Uganda, for livelihood benefits. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 25(6), 717–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-017-9546-y

Government of Uganda (2016). Uganda Wetlands Atlas – Volume Two Popular Version. Ministry of Water and Environment, Kampala UGANDA.

Grimble, R., & Chan, M.-K. (1995). Stakeholder analysis for natural resource management in developing countries. Natural Resources Forum, 19(2), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-8947.1995.tb00599

Gupta, G., Khan, J., Upadhyay, A. K., & Singh, N. K. (2020). Wetland as a sustainable reservoir of ecosystem services: Prospects of threat and conservation. In A. K. Upadhyay, D. P. Ranjan Singh, & Singh, (Eds.), Restoration of Wetland ecosystem: A trajectory towards a sustainable environment (pp. 31–43). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7665-8_3

Hartter, J., & Ryan, S. J. (2010). Top-down or bottom-up? Decentralization, natural resource management, and usufruct rights in the forests and wetlands of western Uganda. Journal Land Use Policy, 27, 815–826.

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Hopkins, T. S., Bailly, D., Elmgren, R., Glegg, G., Sandberg, A., & Støttrup, J. G. (2012). A systems approach framework for the transition to sustainable development: Potential value based on coastal experiments. Ecology and Society. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05266-170339.

Horwitz, P., Finlayson, M. and Weinstein, P. (2012). Healthy wetlands, healthy people. A review of wetlands and human health interactions. Published jointly by the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands and the World Health Organisation. Ramsar Technical Report No. 6. Gland, Switzerland.

Isunju, J. B., Orach, C. G., & Kemp, J. (2016). Hazards and vulnerabilities among informal wetland communities in Kampala. Uganda. Environment and Urbanization, 28(1), 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247815613689.

Jiang, B., Wong, C. P., Chen, Y., Cui, L., & Ouyang, Z. (2015). Advancing wetland policies using ecosystem services – China’s way out. Wetlands, 35(5), 983–995. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-015-0687-6.

Kakuba, S. J., & Kanyamurwa, J. M. (2021). Management of wetlands and livelihood opportunities in Kinawataka wetland, Kampala-Uganda. Environmental Challenges, 2, 100021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2020.100021.

Kakuru, W., Turyahabwe, N., & Mugisha, J. (2013). Total economic value of wetlands products and services in Uganda. The Scientific World Journal, 2013, e192656. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/192656.

Kalanzi, W. (2015). Local governments and wetland conservation in Uganda: Contributions and challenges. Journal of Public Administration, 50(1), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC175611.

Kariuki, M., Thomas, D., Magero, C., & Schenk, A. (2016). Local people and government working together to manage natural resources: Lessons from Lake Victoria Basin. Nairobi: Birdlife Africa.

Keddy, P., & Fraser, L. H. (2000). Four general principles for the management and conservation of wetlands in large lakes: The role of water levels, nutrients, competitive hierarchies and centrifugal organization. Lakes & Reservoirs: Science, Policy and Management for Sustainable Use, 5(3), 177–185. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1770.2000.00111.x.

Kingsford, R. T., Bino, G., Finlayson, C. M., Falster, D., Fitzsimons, J. A., Gawlik, D. E., Murray, N. J., Grillas, P., Gardner, R. C., Regan, T. J., Roux, D. J., & Thomas, R. F. (2021). Ramsar wetlands of international importance-improving conservation outcomes. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 9, 53. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2021.643367.

Mafabi, P (2018). National wetland policy: Uganda, environment affairs, ministry of water and environment, Kampala, Uganda.

Mbabazi, J., Wasswa, J., Kwetegyeka, J., & Bakyaita, G. K. (2010). Heavy metal contamination in vegetables cultivated on a major urban wetland inlet drainage system of Lake Victoria. Uganda. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 67(3), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207231003612613.

McInnes, R. J. (2013). Recognizing Ecosystem Services from Wetlands of International Importance: An Example from Sussex. UK. Wetlands, 33(6), 1001–1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-013-0458-1.

McNally, C. G., Gold, A. J., Pollnac, R. B., & Kiwango, H. R. (2016). Stakeholder perceptions of ecosystem services of the Wami River and Estuary. Ecology and Society. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08611-210334.

Mengesha, T. A., & Mengesha, T. A. (2017). Review on the natural conditions and anthropogenic threats of Wetlands in Ethiopian. Global Journal of Ecology, 2(1), 006–014. https://doi.org/10.17352/gje.000004.

Meyer, C. (2018). Perceptions of the environment and environmental issues in Stellenbosch, South Africa: A mixed-methods approach [Thesis, Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University]. https://scholar.sun.ac.za:443/handle/10019.1/104937.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Program). (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: Synthesis. Island Press.

Miller, S. M., & Montalto, F. A. (2019). Stakeholder perceptions of the ecosystem services provided by green infrastructure in New York City. Ecosystem Services, 37, 100928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.100928.

Ministry of Water and Environment. (2016). Uganda wetlands atlas – volume two, ministry of water and environment.

Ministry of Water and Environment. (2019). State of wetlands report for Uganda.

Moomaw, W. R., Chmura, G., & Davies, L. (2018). Wetlands in a changing climate: Science, policy and management. Wetlands, 38(2), 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-018-1023-8

Morrison, E. H. J., Upton, C., Odhiambo-K’oyooh, K., & Harper, D. M. (2012). Managing the natural capital of papyrus within riparian zones of Lake Victoria. Kenya. Hydrobiologia, 692(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-011-0839-5.

Musasa, T., & Marambanyika, T. (2020). Threats to sustainable utilization of wetland resources in ZIMBABWE: A review. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 28(4), 681–696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-020-09732-1.

Muwanguzi, I. (2018). Attitudes of communities towards wetland conservation programmes: A case of Lutembe Bay Wetland, Wakiso District, Uganda Thesis, Makerere University. http://makir.mak.ac.ug/handle/10570/6888.

Nakiyemba, A. W., Isabirye, M., Poesen, J., Deckers, J., & Mathijs, E. (2020). Stakeholders’ Perceptions of the Problem of Wetland Degradation in the Ugandan Lake Victoria Basin Uganda. Natural Resources, 11, 218–241. https://doi.org/10.4236/nr.2020.115014.

Namaalwa, S. (2013). A characterization of the drivers, pressures, ecosystem functions and services of Namatala wetland, Uganda. Environmental Science & Policy, 34, 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.01.002.

Omoding, J., Walters, G., Andama, E., Carvalho, S., Colomer, J., Cracco, M., Eilu, G., Kiyingi, G., Kumar, C., Langoya, C. D., Nakangu Bugembe, B., Reinhard, F., & Schelle, C. (2020). Analysing and applying stakeholder perceptions to improve protected area governance in Ugandan conservation landscapes. Land, 9(6), 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060207.

Ondiek, R. A., Vuolo, F., Kipkemboi, J., Kitaka, N., Lautsch, E., Hein, T., & Schmid, E. (2020). Socio-economic determinants of land use/cover change in wetlands in East Africa: A case study analysis of the Anyiko Wetland, Kenya. Frontiers in Environmental Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2019.00207.

Ostrovskaya, E., Douven, W., Schwartz, K., Pataki, B., Mukuyu, P., & Kaggwa, R. C. (2013). Capacity for sustainable management of wetlands: Lessons from the WETwin project. Environmental Science & Policy, 34, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.08.006.

Pluchinotta, I., Pagano, A., Giordano, R., & Tsoukiàs, A. (2018). A system dynamics model for supporting decision-makers in irrigation water management. Journal of Environmental Management, 223, 815–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.06.083.

Pueyo-Ros, J., Ribas, A., & Fraguell, R. M. (2019). A cultural approach to wetlands restoration to assess its public acceptance. Restoration Ecology, 27(3), 626–637. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.12896.

Ramsar Convention Secretariat (2005). What are wetlands? Ramsar Information P. 1.

Ramsar Convention Secretariat (2010). Wise use of wetlands: Concepts and approaches for the wise use of wetlands. Ramsar handbooks for the wise use of wetlands, (4th ed) vol. 1. Ramsar Convention Secretariat, Gland, Switzerland. https://www.ramsar.org/handbooks.

Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. (2018). Global wetland outlook: State of the world’s wetlands and their services to people. Gland: Ramsar Convention Secretariat.

Ranganathan, J., Raudsepp-Hearne, C., Lucas, N., Irwin, F. H., Zurek, M. B., Bennett, K., Ash, N., West, P., World Resources Institute. (2008). Ecosystem services: A guide for decision makers. World Resources Institute.

Ruiz-Frau, A., Krause, T., & Marbà, N. (2018). The use of sociocultural valuation in sustainable environmental management. Ecosystem Services, 29, 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.12.013.

Russi D., ten Brink P., Farmer A., Badura T. (2013). The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity for water and wetlands. IEEP, London and Brussels; Ramsar Secretariat, Gland.

Sandhu, H., Crossman, N., & Smith, F. (2012). Ecosystem services and Australian agricultural enterprises. Ecological Economics, 74, 19–26.

Sandhu, H., & Sandhu, S. (2014). Linking ecosystem services with the constituents of human well-being for poverty alleviation in eastern Himalayas. Ecological Economics, 107, 65–75.

Schuyt, D. K. (2005). Economic consequences of wetland degradation for local populations in Africa. Journal of Ecological Economics, 53, 177–190.

Simaika, J. P., Van Dam, A. A., & Chakona, A. (Eds.). (2021). Towards the sustainable use of African wetlands. Frontiers Media SA.

Sinthumule, N. I. (2021). An analysis of communities’ attitudes towards wetlands and implications for sustainability. Global Ecology and Conservation, 27, e01604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01604.

Sowińska-Świerkosz, B., & García, J. (2021). A new evaluation framework for nature-based solutions (NBS) projects based on the application of performance questions and indicators approach. Science of the Total Environment, 787, 147615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147615.

Spangenberg, J. H., Görg, C., & Settele, J. (2015). Stakeholder involvement in ESS research and governance: Between conceptual ambition and practical experiences – risks, challenges and tested tools. Ecosystem Services, 16, 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2015.10.006.

Tumusiime T.T.M (2013). The contribution of wetland resources management to household food security in Nangabo subcounty, Wakiso District. Uganda, Uganda Management Institute Masters Dissertation.

Tumuhimbise I (2017). Spatio-temporal changes in land use patterns influencing the size of Namulomge wetland, Wakiso District, central Uganda. Masters Thesis, Kenyatta University.

Turyasingura, B., Hannington, N., Kinyi, H. W., Mohammed, F. S., Ayiga, N., Bojago, E., Benzougagh, B., Banerjee, A., & Singh, S. K. (2023). A Review of the effects of climate change on water resources in Sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Climate Change and Resource Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.37284/ajccrs.2.1.1264.

Verhoeven, J. T. (2014). Wetlands in Europe: Perspectives for restoration of a lost paradise—ScienceDirect. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925857413001109?casa_token=bKx9Flz_YfAAAAAA:RWsKOD9J05EWYSA9-ZdPCU1F_BCbQdwYgswby8OzYe-Qx2bfvan3y6rc_ghf0bHdWFgNI2U.

Wakiso District Local Government (2017). Physical Development Plan (2018–2040). Unpublished.

Wamala, S. M. (2021). Assessing the factors that influence encroachment on Lubigi wetland [Thesis, Makerere University]. http://dissertations.mak.ac.ug/handle/20.500.12281/8952.

Warbington, C. H., & Boyce, M. S. (2023). Water-level fluctuations and ungulate community dynamics in central Uganda. Water. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15152765.

Wratten, S., Sandhu, H., Cullen, R., & Costanza, R. (Eds.). (2013). Ecosystem services in agricultural and urban landscapes. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Xu, X., Chen, M., Yang, G., Jiang, B., & Zhang, J. (2020). Wetland ecosystem services research: A critical review. Global Ecology and Conservation, 22, e01027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01027.

Zainal, Z. (2007). Case study as a research method. 6.

Zhang, H., Pang, Q., Long, H., Zhu, H., Gao, X., Li, X., Jiang, X., & Liu, K. (2019). Local residents’ perceptions for ecosystem services: A case study of Fenghe River Watershed. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193602.

Zhao, Q., Bai, J., Huang, L., Gu, B., Lu, Q., & Gao, Z. (2016). A review of methodologies and success indicators for coastal wetland restoration. Ecological Indicators, 60, 442–452.

Zingraff-Hamed, A., Hüesker, F., Lupp, G., Begg, C., Huang, J., Oen, A., Vojinovic, Z., Kuhlicke, C., & Pauleit, S. (2020). Stakeholder mapping to co-create nature-based solutions: Who is on board? Sustainability, 12(20), 8625. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208625

Zsuffa, I., Cools, J., Vlieghe, P., Debels, P., van Griensven, A., van Dam, A., Hein, T., Hattermann, F., Masiyandima, M., Cornejo, M. P., de Grunauer, R., Kaggwa, R., & Baker, C. (2016). The WETwin project: Enhancing the role of wetlands in integrated water resources management for twinned river basins in the EU, Africa and South-America in support of EU water initiatives. In J. Fehér (Ed.), Watershed and river basin management. Trivent Publishing. https://doi.org/10.22618/TP.EI.20162.120006.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to all the stakeholders that participated in this study from Lutembe Bay and Nabaziza wetland communities, Wakiso District and national-level stakeholders.

Funding

The research was part of Anthony Kadoma PhD sponsored by the University of Glasgow College of Social Sciences PhD Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, data analysis and the first draft of the manuscript were done by AK. FGR and MP supervised the study. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript, and they read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicting interest whether personal or financial that could have influenced the work reported in this article.

Ethical approval

This study and its tools were approved by the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology and University of Glasgow College of Social Sciences Ethics Committee.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.