Abstract

In this work, we simulate the effects of the tax autonomy of the Austrian states on the levels of public employment in each state. We show that depending on the strength of the public sector lobby, tax autonomy would require a reduction of employment in the public sector of between 25 and 35% of the current level. We also show that tax autonomy increases welfare levels by 1–1.5%; that is, the positive change in the disposable income of the workers more than offsets the welfare loss resulting from the lower provision of public goods. Finally, we show that the reduction of public employment is superior in terms of welfare to an alternative scenario in which employment levels are held constant but the wage levels in the public sector are adjusted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This is a simplifying assumption, as in the course of the negotiations of fiscal equalization laws, the states’ representatives unquestionably bring substantial power to bear.

This number was higher until the end of 2012, which saw a major wave of municipal amalgamations in the federal state of Steiermark.

The actual shares of joint taxation for each state result from a fairly complex calculation which includes additions and deductions as stipulated in §10(2) of the FAG.

The states will become fully autonomous with tax-rate discretion in the latter contribution, starting from the fiscal year 2018.

Here this is given in simplified form. The full budget constraint additionally involves transfers from the central budget, and can be obtained upon request.

At the time of the simulation, data for the year 2014 was used. Data for 2015 is currently available (Popp 2016] which is, however, marginally different from the data used in this study (employment rose between 2014 and 2015 by 1502 persons).

This assumption corresponds closely to the actual employment contracts of civil servants.

Alternatively, surcharges on income taxation could be visualized. However, since income taxation is progressive, this would require additional assumptions regarding authority over setting the progressivity of the system, as well as the exact shape of the income distribution.

This is a simplifying assumption for the case of income taxation, since we are not able to determine the changes in the structure of earnings. It is accurate for corporate taxation, however, as this is subject to a flat rate.

This is in comparison to 53% for the general population.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable data on the parliamentary election choices of different employment groups. We therefore analyze the sensitivity of the results to the assumptions about the strength of the political distortion.

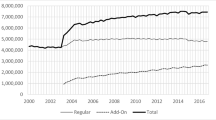

Figures in the first column are based on the states’ reports on public employment (including outsourced services–“Ausgliederungen”) required by the Austrian Stability Pact.

The average under fiscal equalization does not change compared to the tax autonomy, since the explicit fiscal transfers simply redistribute the public means between the states.

The “jumps” in the progression of the curve stem from rounding up the wage levels to the second decimal place.

References

Andrews M, Duncombe W, Yinger J (2002) Revisiting economies of size in American education: are we any closer to a consensus? Econ Educ Rev 21(3):245–262

Ansolabehere S, Snyder JM (2006) Party control of state government and the distribution of public expenditures. Scand J Econ 108(4):547–569

Bauer et al (2010) Grundsätzliche Reform des Finanzausgleichs: Verstärkte Aufgabenorientierung. Institut für Höhere Studien (IHS), Wien

Brennan G, Buchanan JM (1977) Towards a tax constitution for Leviathan. J Public Econ 8(3):255–273

Brennan G, Buchanan JM (1980) The power to tax: analytic foundations of a fiscal constitution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bröthaler et al (2011) Grundlegende Reform des Finanzausgleichs: Reformoptionen und Reformstrategien. Technische Universität Wien

de Castro F, Salto M, Steiner H et al (2013) The gap between public and private wages: new evidence for the EU. Tech. rep., Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission

Die Presse (2014) Gewerkschaft öffentlicher Dienst: Ergebnisliste der Bundes–Personalvertretungswahlen–2014

Eggert W, Sørensen PB (2008) The effects of tax competition when politicians create rents to buy political support. J Public Econ 92(5):1142–1163

Falch T, Strøm B (2005) Wage bargaining and political strength in the public sector. CESifo Working Paper No 1629

Fuest C (2000) The political economy of tax coordination as a bargaining game between bureaucrats and politicians. Public Choice 103(3–4):357–382

Keen M, Kotsogiannis C (2003) Leviathan and capital tax competition in federations. J Public Econ Theory 5(2):177–199

Keuschnigg C, Loretz S (2015a) Finanzautonomie der Bundesländer. Universität St Gallen, FGN-HSG, WPZ, Eine Finanzpolitik näher am Bürger

Keuschnigg C, Loretz S (2015b) Macht braucht Verantwortung: Warum die Länder ihre Ausgaben über eigene Steuern finanzieren sollten. WPZ Analyse Nr 8

Oates WE (1972) Fiscal federalism. Harcourt, New York

Persson T, Tabellini G (2000) Political economics: explaining public policy. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Popp D (2015) Personal im Verantwortungsbereich der Bundesländer: Ergebnisse der Erhebung 2014. Tech. rep., Bundeskanzleramt Österreich

Popp D (2016) Personal im Verantwortungsbereich der Bundesländer: Ergebnisse der Erhebung 2015. Tech. rep., Bundeskanzleramt Österreich

Rechnungshof (2016) Maßnahmen des Landes Kärnten zur Begrenzung des Personalaufwands. Bericht des Rechnungshofes: Kärnten 2016/1

Strohner et al (2015) Abgabenhoheit auf Länder- und Gemeindeebene. EcoAustria - Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung

Visser J (2006) Union membership statistics in 24 countries. Mon Labor Rev 129:38–49

Visser J (2015) ICTWSS data base. Version 5.0. Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies AIAS, Amsterdam

Wilson JD (1999) Theories of tax competition. Natl Tax J 52(2):269–304

Wilson PW, Carey K (2004) Nonparametric analysis of returns to scale in the us hospital industry. J Appl Econ 19(4):505–524

Zodrow GR, Mieszkowski P (1986) Pigou, Tiebout, property taxation, and the underprovision of local public goods. J Urban Econ 19(3):356–370

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge suggestions from the editor and the anonymous referees, which have significantly improved the paper. We also gratefully acknowledge the suggestions and advice of Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik, Gerhard Reitschuler, participants in the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Austrian Economic Association and our colleagues who contributed to previous versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Sensitivity analysis of the model

We demonstrate the sensitivity of our results to the basic assumption of the support from the public sector lobby for the government. We allow this to vary between the value of 53% in the general population, and 80%. Figures 18 and 19 summarize these findings, which present the population-averaged changes in the outcomes of the model in the baseline case of no autonomy for each value of political distortion.

As shown in Fig. 18, for any value of political distortion, tax autonomy leads to a decrease in public employment, and consequently in the provision of public services and overall expenditure on public wages. For higher values of political distortion, however, the expected change is lower. For the basic scenario, of \(p_o=79\%\), public employment is reduced on average by 24%, expenditure on public wages by 21% and the provision of public goods by 9%. In the opposite case, in which the strength of the public lobby is lower, the changes resulting from tax autonomy are −37, −35 and −14%, respectively.

In all cases, tax autonomy is associated with an increase in disposable income, both for public and private employees, and an overall positive change in average welfare. Stronger changes are expected when political distortion is lower. Depending on the value of the political distortion, the change in disposable income varies between +3 and +4.5%, and the change in overall welfare between 0.9 and 1.5%.

Figure 20 presents the relationship between support for the government from the public sector lobby and the public wage level necessary to keep public employment constant.Footnote 14 If the political distortion is low, tax competition will have a stronger impact on tax rates; therefore, the budget constraint would require a higher decrease in public wages, namely to a level of 62% of the current wage, if the state government decides to keep employment levels constant. On the other hand, for high values of political distortion, tax autonomy would force a drop in wages to a level of 75% of the current wage, keeping employment constant. As shown in the previous subsection, all of these changes would be inferior in terms of welfare to the case of a decrease in public employment levels without affecting wages.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Christl, M., Köppl–Turyna, M. Tax competition and the political economy of public employment: a model for Austria. Empirica 45, 607–638 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9379-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9379-1