Abstract

Temperament is a widely researched trait that significantly influences children’s lives. Still, theorists differ in their perspectives on the construct. With their nine dimensions of temperament and three “categories” of children—easy, difficult, or slow to warm up—Thomas and colleagues (1968) laid the foundation for future temperament research. Subsequent researchers have identified temperament profiles that are similar to but not completely consistent with Thomas and colleagues’ model. Still, most conceptualizations exist primarily for researchers and may be challenging to translate for educators who work directly with children and their caregivers. Therefore, this study had two aims. First, we used cluster analysis to corroborate and extend research that categorized children into temperament groups. We identified four groups that converge and one group that diverges from previous findings. Our second, more important purpose was to strengthen the link between research and practice by conceptualizing our results in a way that is understandable to educators and caregivers. The challenging task of capturing the nature of each cluster in one or even a few words led us to adopt a zoomorphic approach in which we assigned nonhuman animal names to each group: koalas, penguins, dogs, bobcats, and giraffes. Our findings support previous groupings of children by temperament and provide a consumer-friendly model that facilitates communication between caregivers and educators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Temperament plays an important role in numerous childhood academic, social, and behavioral outcomes. A well-established body of literature attests to its important role in young children’s development. Children’s temperaments are linked to their academic performance (Dare et al., 2021; Nasvytienė et al., 2021) and skill development (Viljaranta et al., 2015), social competence (Veziroglu-Celik, 2023), understanding of emotions (Longobardi et al., 2017), and relationships with teachers (Acar et al., 2021), peers (Magdalena, 2015), and parents (Fleck et al., 2024; Walsh & Zadurian, 2023). Of particular concern are findings indicating that temperament predicts externalizing (Brown et al., 2022) and internalizing (Buzzell et al., 2017) disorders and increased risk of psychotic disorders in adulthood (Brannigan et al., 2020). Of specific relevance for preschool children is Bair and Raver’s (2015) contention that temperament—in terms of reactivity and self-regulation—forms the foundation for school readiness.

Preschool children are in a developmentally “busy” stage, as many aspects of school readiness—cognitive, social, and behavioral competencies—must be mastered for a successful transition to school. This transition can be challenging for children, many of whom must adjust to being away from home and familiar people for the first time. The requirements of school are typically “tighter” than those for home, as children must learn to sit quietly for periods of time and interact with unfamiliar peers. Temperament plays an important role in the quality of children’s relationships with adults (Bair & Raver, 2015; Zee & Roorda, 2018) and peers (Magdalena, 2015); those relationships are critical for children’s adjustment to school. With that in mind, it becomes evident that caregivers, educators, and children would benefit from knowing what temperament is, why it is important, and how understanding it can be helpful. Indeed, knowledge of temperament helps teachers (McClowry et al., 2010; Sealy et al., 2021) and parents (O'Connor et al., 2012) respond more effectively to children’s behaviors and better understand their needs (Sealy et al., 2021). Interventions for parents, children, and teachers that incorporate temperament have proven effective. For example, INSIGHTS Into Children’s Temperaments (McClowry, 2002a) is an evidence-based program that informs parents, teachers, and children about temperament and teaches optimal responses to children’s behaviors. Multiple studies have demonstrated the program’s success in improving children’s behaviors (Cappella et al., 2015; McClowry et al., 2010) and teachers’ classroom management skills (McClowry et al., 2010; McCormick et al., 2015). This evidence clearly illustrates the possibility that temperament can and should guide educational efforts with children.

Early childhood educators recognize the importance of considering temperament in teaching (National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2020). The most recent National Association for the Education of Young Children (2020) position statement on Developmentally Appropriate Practice for Young Children includes among its guidelines that, in addition to individual characteristics such as age and ability, teachers should consider temperament when deciding on learning approaches for children. Years ago, Pullis and Cadwell (1985) argued that temperament should be included in school-based, early childhood assessments. Keough (2003) also emphasized the value of including temperament data for teachers and clinical and school-based practitioners, noting that knowledge of temperament can help teachers improve their interactions with students, which may consequently reduce stress. This consequence is promising, as teachers experience approximately twice the rate of stress as other working adults (RAND, 2022) and many exit the profession early, citing stress as one of the top reasons for leaving (Doan et al., 2023). Practitioners that would benefit from temperament knowledge, such as mental health counselors, child and family social workers, marriage and family therapists, have also been rated in the top 20 most stressful occupations in the United States (Ingram & Barbera, 2023). A more promising statistic from Doan et al. (2023) is that teachers who intend to continue teaching noted opportunities to positively impact students and develop positive relationships with them as reasons to continue teaching. Existing research suggests that temperament knowledge could help teachers and other early childhood practitioners successfully accomplish those things (McClowry et al., 2010; McCormick et al., 2015), so calling for increased applications of temperament-informed classroom interactions is warranted.

Despite the acknowledged importance of understanding temperament in classroom interactions with children, there are still practical limitations to fully realizing these benefits. For example, one study found that parents, as assessed via semi-structured interviews, had little to no knowledge or accurate understandings of temperament and did not consider it in their parenting (Jansen van Rensburg et al., 2016), suggesting that current models of temperament may not be accessible to families and caregivers, leading to a communication gap between educators and caregivers. Although effective temperament-based interventions do exist (McClowry, 2002a), additional models that provides accessible language and easily understandable imagery for conveying information to caregivers are needed. A common conceptualization of temperament could facilitate communication between researchers, educators, and caregivers and could strengthen the research-practice link.

Temperament Models

Researchers generally agree that temperament reflects differences in behavioral styles that are observable early in life and relatively stable throughout the lifespan (Sanson et al., 2004). Despite that agreement, conceptualizations of temperament vary, with established models comprising three (Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981; Thomas et al., 1968), four (McClowry, 2002a), and five (Caspi & Silva, 1995) “types” of children, each with different labels. Prokasky and colleagues (2017) identified six clusters and used different labels than previous researchers. The use of different methodological approaches (e.g., factor analysis vs. cluster analysis; rating scales vs. observations) certainly contributes to the varying groupings. These inconsistencies and insufficient replication studies have been described as problematic (Prokasky et al., 2017); the literature would benefit from additional studies using the most promising methods and analyses.

The models and methods used to conceptualize temperament described here differ, but each has strengths. Thomas and colleagues’ (1968) New York Longitudinal Study served as the foundation for future investigations of temperament. They observed commonalities among children’s temperament dimensions and identified nine dimensions and three “types” of children—Easy, Difficult, and Slow-to-Warm-Up. Caspi and Silva (1995) differentiated groups of children based on observations of their behaviors during cognitive and motor tasks. Using a cluster-analytic technique followed by a one-way ANOVA, they identified 5 groups—inhibited, reserved, undercontrolled, confident, and well-adjusted. McClowry (2002a) used parent ratings and higher-order factor analysis and identified four groups—High Maintenance, Industrious, Social/Eager to Try, and Cautious/Slow to Warm Up. Rothbart’s theory extended temperament beyond the innate indicators of behavioral style and emotional reaction to include biological components, viewing temperament as an interplay between reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981). Rothbart (2011) factor analyzed questionnaire ratings and identified 15 dimensions that combined into three broad types—Surgency, Negative affectivity, and Effortful control. In more recent work, Prokasky and colleagues (2017) used a cluster analysis of parent ratings with three large samples. They derived a six-cluster model with the following types of children—Unregulated, High Reactive, Well-Adjusted, Regulated, Bold, and Average.

Despite those differences, there are parallels between the models presented here. Thomas and colleagues’ (1968) conceptualization, which served as the springboard for subsequent temperament research, included one Easy, one Difficult, and one Slow-to-Warm group. Each of the subsequent models can be mapped onto Thomas et al.’s groups, and there is consensus that all of the models include at least one Easy and one Difficult group; all but Rothbart and Derryberry’s (1981) models include a Slow-to-Warm group. Rothbart and Derryberry (1981), Caspi and Silva (1995), McClowry (2002a), and Prokasky et al. (2017) identified two Easy groups; we contend that Prokasky’s Average group may also be considered easy. With the exception of Prokasky et al., each model includes one group of Difficult children; Prokasky and colleagues identified two Difficult groups. McClowry’s and Prokaski et al.’s models included one Slow-to-Warm group; Caspi and Silva identified two. It appears that across the models, we might expect two to three Easy groups and one to two Difficult and Slow-to-Warm groups. Table 1 presents each model described here and illustrates the parallels between the groups.

Temperament Terminology

In addition to the various numbers of groupings of children, some of the nomenclature may be difficult for some caregivers to comprehend. For example, though Rothbart and Derryberry’s (1981) is one of the most well-known, widely accepted, and studied temperament models, some terms, such as surgency and affectivity, may be unfamiliar and consequently not as useful in conveying meaning to parents as simpler labels, such as McClowry’s (2002a) social/eager to try or Caspi and Silva’s (1995) confident. A trend in some child-focused professions (e.g., school psychologists) is to improve communication with caregivers by increasing the readability of written communication by using “consumer-friendly” language (Lichtenstein & Ecker, 2019). Readability is often calculated using the Flesch Reading Ease statistic (0 = very difficult; 60 = easy; Flesch, 1948) and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (Kincaid et al., 1975). Each of the terms surgency and affectivity demonstrated their complexity on both indicators, with a Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease score of 0 (Very Difficult) and Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 12 (https://originality.ai/readability-checker). Rothbart’s model has undeniably had a positive and robust impact on subsequent temperament research; however, the terminology may not be accessible to parents and caregivers, limiting its potential impact on practice.

Additionally, some existing labels may carry negative connotations. While Thomas et al.’s (1968) easy and slow-to-warm are neutral and easy to understand, their difficult, and Caspi and Silva’s (1995) undercontrolled, may be perceived by caregivers as negative. Chess and Thomas (1996) acknowledged that “difficult” may be perceived as negative and might leave unnoticed a difficult child’s positive characteristics. Although we acknowledge the usefulness of and strong evidence base for Thomas and colleagues’ and Caspi and Silva’s temperament models, we wonder if there may be other, more positive ways to refer to children who are considered difficult.

The Current Study

As described, there is a need for more consistency among temperament models (Prokasky et al., 2017). Each model described here is empirically supported, highly regarded, and among the most well-known conceptualizations of temperament, and each research group employed strong methodology to derive their models. Thomas et al. (1968) qualitatively analyzed information from interviews and observations, providing rich information gathered about the children and the resulting nine temperament dimensions. McClowry (2002a), Rothbart and Derryberry (1981), and Prokasky et al. (2017) examined questionnaire ratings; McClowry (1995) used her School-Age Temperament Inventory (SATI), while Rothbart and Derryberry and Prokasky et al. used Rothbart’s Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart et al., 2001). Caspi and Silva’s use of behavior observations during brief testing situations allowed them to gain valuable information, but the use of a testing situation may reduce reliability and fidelity to less contrived situations. McClowry and Rothbart and Derryberry used factor analysis to derive their groups, whereas Caspi and Silva (1995) and Prokasky et al. (2017) used cluster analysis. Some researchers argue for greater use of person-centered over variable-centered approaches, suggesting that cluster analysis may be preferable for grouping children according to temperament (Howard & Hoffman, 2018). In comparison to variable-centered approaches, such as factor analysis, person-centered approaches are designed to categorize a sample into subpopulations and, in doing so, allow for more specificity and fine-grained detail about the groups (Howard & Hoffman).

Sample characteristics also varied across some of the studies. For example, the majority of children in Thomas and colleagues’ (1968) sample were White, middle to upper-middle-class, with well-educated parents. In contrast, McClowry’s (2002a) sample varied widely on race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Prokasky et al. (2017) replicated their results across three samples; the majority of children were White and well-educated, with middle to middle-high incomes.

In order to identify a model that is consistent with any of the ones described here, it is important to intentionally select methods and analyses that can be more directly compared. We propose that Prokasky and colleagues' (2017) approach, which combines a person-centered method and a psychometrically sound temperament questionnaire that measures seven dimensions of temperament, accomplishes that. The combination of cluster analysis and the CBQ, with its seven dimensions, provides a more granular taxonomy to emerge than has been captured by many researchers, which Prokasky et al. emphasize is needed.

Our study has two aims. First, we attempt to corroborate and extend research that categorized children into temperament groups. We adopted Prokasky et al.’s methodology, using cluster analysis to examine parent ratings on a standardized, norm-referenced temperament rating scale comprising the nine temperament dimensions described by Thomas et al., (1968; See Table 2). Unlike Prokasky et al., we examined a single and much smaller sample. We acknowledge cluster analysis’s sensitivity to sample size and characteristics and the items upon which cases (children here) are clustered and recognize McClowry’s (2002a; citing York & John, 1992) criticism that cluster analysis results in exclusive groups and prohibits membership in multiple groups. However, the technique has the capacity to provide a conceptually clear solution in which all children are classified. Although cluster analysis is an exploratory technique, our expectations for the number of clusters we would find were based on the convergent findings from the research described here (Caspi & Silva, 1995; McClowry, 2002a; Prokasky et al., 2017; Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981; Thomas et al., 1968). We anticipated finding at least one cluster representing each of the three groups identified by most other researchers—easy, difficult, and slow-to-warm.

Our second aim was to develop a model of temperament that could promote communication between educators and caregivers by assigning user-friendly, positively worded labels for the resulting clusters. Keeping in mind current trends to increase the readability and user-friendliness of professional terminology used in schools (Lichtenstein & Ecker, 2019), we hoped to establish language that would enhance educators’ and caregivers’ understanding of temperament, which may strengthen the research-to-practice link and increase the likelihood that the individuals who actually work with children will benefit from what researchers have long known and continue to demonstrate about the importance of temperament.

Method

Participants

Participants included parents of 85 children (46 female, 38 male, 1 not reported) ranging from 38 to 68 months (M = 51.5 months) attending preschools or daycare centers in urban and rural areas of North Carolina and Tennessee. The majority of children and parents were White (93%). Parents were generally well-educated: 38.8% reported their highest level of education was a graduate or professional degree, and 31.8% reported a bachelor’s as their highest degree. Each family completed one questionnaire for each child; some parents completed them together, while for others, just one parent completed them.

Measure

The Behavioral Style Questionnaire (BSQ; McDevitt & Carey, 1996), one of several age-specific questionnaires in the Carey Temperament Scales (Carey & McDevitt, 1995), is a 100-item caregiver rating scale designed to assess the temperament of children 34 to 68 months of age. Caregivers respond to items describing their children’s behaviors on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Almost Never to 6 = Almost Always). The BSQ is based on the nine dimensions of temperament identified by Thomas and colleagues’ (1968). Table 2 provides descriptions of the dimensions and interpretations of what high and low scores reflect (e.g., high activity means very active; high mood means negative mood).

The psychometric properties of the BSQ are generally satisfactory for research, with test–retest reliabilities ranging from 0.67 (Threshold) to 0.94 (Rhythmicity) and alpha reliabilities from 0.47 to 0.80 (Carey & McDevitt, 1995). Substantial evidence for the validity of the BSQ has been provided by studies of the relationships between temperament and clinical diagnoses and other measures (Carey & McDevitt). Psychometric data for the current sample appears in Table 3.

Procedure

Twelve preschool center directors in urban and rural North Carolina and Tennessee were solicited for participation; eleven consented. Centers were identified from the childcare directory search provided by the North Carolina Division of Child Development (https://ncchildcare.ncdhhs.gov/) and by a research team member who had relationships with directors in Tennessee. Teachers distributed packets to parents that contained information about the study, informed consent forms, and stamped envelopes addressed to the researchers. Parents who agreed to participate provided written informed consent on the forms and returned them directly to the researchers via mail. Questionnaires were grouped in counterbalanced order and mailed to participants, who returned the forms to the researchers in self-addressed, stamped envelopes. Participants received monetary compensation ($10 per child) from funds granted by Appalachian State University’s Research Council. This study was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board and was conducted in a manner consistent with its guidelines for research with human subjects.

Data Analysis

A hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s (1963) method with a squared Euclidean distance measure was conducted on the BSQ scale scores. We examined the schedule coefficients to identify likely solutions.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, correlation coefficients, and Cronbach’s alphas for the BSQ scales are presented in Table 3. The current data are largely consistent with those previously reported (Carey & McDevitt, 1995). The internal consistency reliability coefficients in the current data ranged from 0.51 to 0.83 (see Table 3) and were consistent with those presented in the test manual (Carey & McDevitt; ranging from 0.47 to 0.80) and observed by previous authors (e.g., Gibbs et al., 1987; Hubert et al., 1982; Scheier et al., 1995). Alpha reliabilities were below 0.60 for the Rhythmicity (0.55) and Threshold (0.51) subscales. In light of these low alphas, results from these scales should be interpreted cautiously.

Using a Bonferroni corrected alpha of 0.006 (α = 0.05 / 9 tests), the current sample is higher in Rhythmicity (i.e., more regular; current M = 3.04, normative M = 2.75; t = 4.311, p < 0.001) and lower in Intensity (i.e., less intense; current M = 4.25, normative M = 4.52; t = -4.802, p < 0.001), Mood (i.e., more positive; current M = 3.05, normative M = 3.31; t = -3.669, p < 0.001), and Threshold (i.e., needs more stimulation to prompt a response; current M = 3.70, normative M = 3.85; t = -4.64, p < 0.001) than the normative sample. No other statistically significant mean differences were found between the normative and current samples for any other BSQ scales.

With the exception of Activity, girls’ and boys’ BSQ subscale scores were similar. Using a Bonferroni corrected alpha of 0.006 (α = 0.05 / 9 tests), girls were less active (M = 3.33, SD = 0.54) than boys (M = 3.74, SD = 0.56), t(82) = -3.38, p = 0.001. Because only one scale demonstrated sex differences in the current sample, data were collapsed across gender for all analyses.

Cluster Analysis

A hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s (1963) method with a squared Euclidean distance measure was conducted on the BSQ scale scores. The agglomeration schedule coefficients (see Table 4) revealed that, as the initial clusters were separated into additional clusters, the coefficient for Stage 7 was considerably larger than in previous stages, suggesting that the best solution would comprise fewer than 7 clusters. Interpretation of the dendrogram (see Fig. 1) indicated that either 4 or 5 clusters were most appropriate. The steps between 1 and 2 clusters, 2 and 3 clusters, 3 and 4 clusters, and 4 and 5 clusters were all noticeably larger than the step between 5 and 6 clusters. After qualitatively examining the data, it was determined that the 5-cluster solution better fit the data than the 4-cluster solution. First, by examining the sample sizes from the 4 and 5 cluster solutions, it was determined that Cluster 1 from the 4-cluster solution was split into two clusters to form Cluster 5. We examined the means and standard errors of the BSQ subscales for meaningful differences (see Table 5). The 5-cluster solution had many notable differences (using a > 1 SD criterion) between the first and fifth clusters and thus appeared to be the better option.

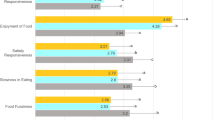

After adopting the 5-cluster solution, the mean BSQ scale scores for each cluster were calculated, plotted—Fig. 2 presents “profiles” across the temperament dimensions for each cluster of children—and converted to z-scores, which can be more helpful than raw scores in the interpretation of BSQ scale scores (see Table 6). According to the Carey Temperament Scales Test Manual (Carey & McDevitt, 1995), scores greater than + 1.0 are considered high; average scores are those between + 1.0 and -1.0, and scores below -1.0 are low.

Following these guidelines, z-scores greater than ± 1 were used to characterize children in the clusters. The following descriptions list temperament dimensions in rank order, starting with the strongest characteristic. Children in Cluster 1 (n = 8; approximately 9% of the current sample) are characterized by positive mood, high threshold, mild intensity, and—if the standard is relaxed slightly to 0.9 SD—low distractibility and low activity. Children in Cluster 2 (n = 16; approximately 19% of the current sample) displayed positive mood and high adaptability. Children in Cluster 3 (n = 34; approximately 40% of the current sample) did not have z-scores at (or approaching) ± 1 on any of the nine temperament dimensions. Children in Cluster 4 (n = 10; approximately 12% of the current sample) displayed negative mood, non-adaptability, and arrhythmicity. Children in Cluster 5 (n = 17; approximately 20% of the current sample) demonstrated positive mood, high threshold, mild intensity, and low persistence (See Fig. 2).

Labeling Identified Clusters

Following the statistical analyses described above that identified five distinct clusters of children characterized by their standing on temperament dimensions, we endeavored to create meaningful and accessible labels to capture the essence of each group. We chose to take a zoomorphic labeling approach informed by an artificial intelligence language model, ChatGPT. Using animal attributes as metaphors to characterize people has been a common practice for some time (Sommer, 2008). Examples of zoomorphism appear in popular publications (Herzog & Galvin, 1992) such as comic books and movies, perhaps reflecting children’s inclination toward animals (Wu et al., 2023). Incorporating animals in instructional videos has demonstrated effectiveness in improving children’s learning (Wu et al.). Moreover, researchers have examined perceptions of personality traits of animals (Sommer & Sommer, 2011).

ChatGPT is a large-scale language model trained on expansive and diverse text data, providing common responses to natural language prompts. All defining temperament dimensions for each identified cluster (e.g., positive mood and high adaptability for Cluster 2) were entered simultaneously in the context of asking ChatGPT to identify animals associated with those particular descriptors, except for Cluster 3, for which there were no outstanding temperament dimensions (we used “average” for this category). For each cluster, ChatGPT suggested a list of potential animal species with those associations. From that list, we endeavored to choose distinct, non-overlapping species with neutral or positive perceptions, eschewing those with negative connotations (e.g., snake, skunk, sloth), resulting in selecting koala, penguin, dog, bobcat, and giraffe as labels for Categories 1–5. Our selections were informed by Sommer and Sommer’s (2011) examination of college students’ perceptions of favorability of animal names of species that were most likely to be associated with human personality traits. Two of our animal names–penguins and bobcats—were rated as favorable, koalas were perceived as equally favorable and unfavorable; however, giraffes and dogs were not rated in Sommer and Sommer’s study.

To further examine the semantic accuracy of our labels, we subsequently used ChatGPT to identify which temperament dimensions were associated with each selected animal label to see if appropriate temperament dimensions were returned. When we were trying to decide between two or more potential animal labels for a category, this helped inform the selection of an appropriate animal label.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was twofold: to corroborate groups of children described by prominent temperament researchers (Caspi & Silva, 1995; McClowry, 2002a; Prokasky et al., 2017; Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981; Thomas et al., 1968) and to use our results as a framework for a user-friendly model of temperament that can facilitate conversations among practitioners and caregivers. A careful review of previous research reveals substantial overlap in how children have been grouped—even though researchers differ on the number and names of the groups. Children generally can be placed into easy, difficult, and slow-to-warm groups, possibly with multiple groups in each category. Based on these commonalities, we anticipated finding at least one each of the following groups—easy, difficult, and slow-to-warm children.

We identified a five-cluster model that included four easy groups and one difficult group; surprisingly, we did not find a slow-to-warm group. Even so, the groups are largely comparable to those identified by Thomas and colleagues (1968), Caspi and Silva (1995), Prokasky et al. (2017), Rothbart and Derryberry (1981), and McClowry (2002a). In the following paragraphs, we carefully examine these five clusters identified through cluster analysis and labeled semantically and compare them to previous findings. Table 1 summarizes the similarities between the current study and previous research.

Cluster 1 (approximately 9% of the current sample) represents an easy group of children that we labeled koalas. These children displayed positive mood, high threshold (i.e., sensitivity), mild intensity, low distractibility, and low activity, and could be considered easygoing. Based upon the item content caregivers used to describe them (McDevitt & Carey, 1978), children in this group tend to laugh and smile often and complain very little when tired, ill, or frustrated. They are not easily distracted by interruptions, such as parental requests or nearby conversations, and tend to sit calmly and quietly while engaging in activities or waiting for things. Their high sensitivity to events in their environments may leave them susceptible to mild approval and disapproval, noises, and injuries, and they may notice minor changes in the people or events around them (e.g., a parent’s haircut, foods). This group of children is likely to respond mildly to their environments; despite their high sensitivity, they do not react overly intensely. In a classroom or group setting, our koalas would likely engage positively with other children and maintain focus on activities and interactions. When compared to previous studies, these children most resemble Thomas et al.’s (1968) Easy group, Caspi and Silva’s (1995) and Prokasky et al.’s (2017) Well-Adjusted groups, McClowry’s (2002a) Industrious, and Rothbart and Derryberry’s (1981) Effortful Control groups.

Cluster 2 (~ 19%) represents another easy group of children that we labeled penguins. These children displayed positive mood and high adaptability and may tend to “go with the flow” and be considered even-tempered. Based upon the BSQ item content, parents characterized these children as happy during play and when meeting new people. They adjust easily to changes in plans and routines at home and school, learn new things quickly and easily, and take setbacks in stride. In contrast to the koalas, penguins have average levels of intensity, distractibility, activity, and threshold, or sensitivity. Children in this group may be expected to interact easily with others in social situations, settle conflicts quickly, and readily change their behaviors in response to punishment. Based on this combination of traits, these children should be relatively easy for caregivers and teachers to manage. When compared to previous studies, our penguins resemble Thomas and colleagues’ (1968) Easy, McClowry’s (2002a, 2002b) Social/Eager to Try, Caspi and Silva’s (1995) Confident, Prokaski and colleagues’ (2017) Bold, and Rothbart and Derryberry’s (1981) Surgency groups.

Cluster 3 (~ 40%) represents a group of children without notably high or low scores on any of the nine temperament dimensions and did not readily fit into easy, difficult, or slow-to-warm groups. Because of their ubiquitous nature and the large number of breeds, we labeled our largest category dogs. These children could be considered moderate or neutral. According to their caregivers’ ratings, these children display developmentally typical levels of all temperament dimensions. This category seems much like Caspi and Silva’s (1995) Well-Adjusted children, Rothbart and Derryberry’s (1981) Effortful Control, and Prokaski and colleagues’ (2017) Average groups, but did not appear to fit with any of McClowry’s (2002a) groupings. McClowry et al. (2013) describe an “intermediate” group, but upon close inspection, only the name is comparable; intermediate children were described as displaying aggression, disruptive behaviors, and attentional difficulties. McClowry’s (2002a) study also found that most of the children did not fit into any of her four groups. Moreover, the largest group of children in our study and that of Caspi and Silva (1995)—40% of each sample—are children who are remarkable in their “average-ness.” Since both Caspi and Silva and the current authors used cluster analysis, a process that forces every individual into a group, it is possible that we, McClowry, and Caspi and Silva identified the same kind of moderate children through different methods.

Cluster 4 (~ 12%) represents a challenging group of children, which we labeled bobcats. These children displayed negative mood, low adaptability and rhythmicity, and might be described as difficult. Children in this group may be unpleasant, troubled by new situations or changes in routine, and unpredictable in their bodily functions (eating, sleeping, toileting). According to their parents, children in this group may request to eat at irregular times and have trouble falling asleep at the same time every day. These children may cry or whine when frustrated or sick, frown when asked to comply with chores, and become annoyed if others interrupt them during play. They are bothered by changes in plans or routines, slow to adapt, and need time to adjust. This combination of traits can make them challenging during interpersonal interactions and in group situations. Peers and caregivers may find it unpleasant to interact with them because of their negative and often unpredictable moods, which may cause them to sulk when corrected or to display anger toward peers. Planning activities for young children whose biological functions are unpredictable can be challenging for caregivers, as they may not be able to anticipate the need for restroom breaks or naps. To accommodate their low adaptability, caregivers must anticipate changes that may challenge these children and prepare them as early as possible. This combination of characteristics may require high levels of energy by parents and teachers to effectively respond to these children, often while they simultaneously care for multiple children. Our bobcats are very similar to Thomas and colleagues’ (1968) Difficult, Caspi and Silva’s (1995) Undercontrolled, Rothbart and Derryberry’s (1981) Negative Affectivity, McClowry’s (2002a) High Maintenance, and Prokaski et al.’s (2017) Unregulated and High Reactive groups.

Cluster 5 (~ 20%) shares three of the five “easy” traits that characterize the koalas group, including positive mood, high threshold of responsiveness, and mild intensity. Unlike the koalas, this group displays moderate activity and distractibility but low levels of persistence. We labeled this group giraffes. The combination of their positive mood, high sensitivity, mild intensity, and low persistence may characterize these children as “low-key” or “carefree.” Like the koalas, children in this group are generally happy and laugh and smile often. Although they are highly sensitive to stimuli, such as noise, approval or disapproval by caregivers, and minor changes in familiar people or foods, their responses to positive or negative events are mild. Not only are these children relatively easy in terms of mood and intensity, but they also display low activity and distractibility, which promote success in learning and play activities. Our giraffes demonstrate low levels of persistence, which suggests they may become quickly bored or disinterested in new toys or activities and give up on activities prematurely. Their low persistence may make these otherwise easy children somewhat challenging in learning situations and play interactions. In group settings, they may be well-liked and easy to get along with because of their positive mood and low intensity, but caregivers may find it challenging to maintain their interest in tasks or activities. Our giraffes fit with Thomas and colleagues’ (1978) Easy group but are unlike the easy groups described by Caspi and Silva (1995), Rothbart and Derryberry (1981), McClowry (2002a), or Prokasky et al. (2017). Thus, it represents a new group of easy children.

It is noteworthy and unexpected that our data did not identify a slow-to-warm-up group. Previous temperament theorists have consistently observed variations in characteristics such as withdrawal (Thomas et al., 1968), social fearfulness (Goldsmith, 1996), and shyness (Rothbart & Derryberry, 1981) and identified groups of children who consistently display these traits. Although we do not have data to inform an explanation for the absence of a slow-to-warm category in our study, perhaps the high level of parental education allowing for higher familial resources could have provided a richer environment encouraging social-emotional development.

Overall, our findings suggest that despite diverse conceptualizations of temperament and disparate methodologies, a remarkably consistent portrait of children and their temperaments has emerged across studies. The general consensus is that there is a group of easy children (with subtypes, perhaps), a group of difficult children, a group of children who are generally positive but shy and not so adaptable or persistent, and a large group of children who do not fit into these groups.

One major strength of this study is that it confirms and integrates previous work. Our methodology and results align closely with Prokasky and colleagues’ (2017), albeit with a much smaller and single sample. We recognize and later describe aspects of our study that limit its generalizability, but we contend that the combination of measurement and analysis we used adds value to our findings and is different than most other approaches (Prokasky et al.’s aside). Person-centered approaches are considered more appropriate to use than variable-centered, and we considered cluster analysis to be the best method for discovering subgroups. Additionally, data from caregiver ratings on a standardized temperament questionnaire provides valuable information from caregivers about their children’s behaviors across multiple settings and times, which can increase the ecological validity of findings. The BSQ provides information on nine dimensions of temperament, which responds to Prokasky et al.’s (2017) call for studies using more fine-grained measures.

Another strength of our study is the novel approach to naming clusters. Those who work with young children and families can appreciate the difficulty in conveying assessment results to caregivers. While our study is limited and exploratory, we hope that our zoomorphic approach will spark interest in developing new nomenclatures for use in practice settings. McClowry’s (2002b) INSIGHTS program uses puppets with temperament-based names (e.g., Hillary the Hardworker), which has proven to be a very effective approach for improving child, parent, and teacher outcomes (Cappella et al., 2015; McClowry et al., 2010, 2013; O'Connor et al., 2012). An advantage of using animals is that it avoids gendering categories.

Implications

Our findings have implications for caregivers and teachers of preschoolers. School-based early childhood assessments and interventions rarely formally measure temperament (Carey, 1998). In their recent report of the test use and assessment practices of school psychologists across the United States, Benson et al. (2019) found that out of the 150 specific tests reportedly used, none were measures of temperament; three measures of personality were used, and two of these were rarely used in practice. Our findings bridge the research-to-practice gap by providing a common language for understanding and communicating information about child temperament. Early childhood educators receive little training in individual differences, such as temperament. Although they may learn about managing student behaviors, those who appreciate the importance of temperament recognize that behavior management is not a “one-size-fits-all” endeavor. Scholars understand what terms such as “surgency” and “rhythmicity” mean, but most parents and early childhood professionals do not. We know that when parents and educators understand temperament, they are better equipped to support children (McClowry et al., 2010; McCormick et al., 2015). Our use of animal names provides a starting point for conversations and professional development.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. Cluster analytic techniques are dependent on the characteristics and size of the sample. Our sample’s small size (N = 85), small number of children in each cluster, and homogeneity (primarily White children with well-educated parents) limit the generalizability of our results. We note that, although Prokasky et al.’s (2017) study involved three much larger samples and their replication across the samples makes their results quite robust, the demographic characteristics of their samples are similar to ours. Additionally, direct comparisons of the current clusters to previous categories may not be appropriate because of age differences in the samples examined and the data collection methods and measures. For example, McClowry’s (2002a) sample consisted of kindergarten and primary school-aged children, whose temperaments tend to be more stable than younger children. Children in our sample were similar in age to Prokaski and colleagues’ samples (range = 37 to 68 months). Additionally, the BSQ is based on Thomas and colleagues’ (1968) nine dimensions of temperament. Even though we discovered commonalities across existing temperament theories, we acknowledge that using a specific theory-driven measurement tool may have influenced our findings. However, as with the sample characteristics, our use of a fine-grained questionnaire with research support is consistent with Prokasky et al. Despite the limitations we describe here, the similarity of our results to others may speak to the robustness of the findings.

An additional methodological concern is the low reliabilities observed on some BSQ scales. Although we acknowledge that alpha values below 0.60 may impact the interpretation of the results, this issue is not uncommon in research examining the BSQ and has been addressed by other researchers. For example, Barger et al. (2019) found alphas of 0.57, 0.59, and 0.37 on the Persistence, Rhythmicity, and Threshold scales, respectively. Moreover, Huelsman et al. (2013) proposed that some scales are developed to produce a set of divergent items to assess the breadth of the constructs, as opposed to a more homogeneous set of items to measure a particular characteristic. Behavioral manifestations of temperament may vary across time, context, and development. As such, the individual items on the BSQ temperament scales address the variety of behaviors that are reflected in each temperamental trait. For example, Huelsman and colleagues noted that while children may demonstrate consistent eating and sleeping patterns, their bowel and bladder functions might be less consistent, yielding a lower index of internal consistency reliability for the Rhythmicity scale. Still, results from scales with low reliabilities are a concern. To address this problem, Rothbart and Mauro (1990) emphasize the importance of examining both a scale’s definition and its items in order to understand what is being assessed.

Though we consider the use of animal names for our clusters to be a strength and the innovative contribution of our study, we recognize that this approach may engender questions from temperament researchers and practitioners. Several equity-related issues influenced our decision to use animal names. There is evidence that both African American and White individuals report similar levels of animal-liking and preferences (Richardson et al., 2020). Although that study only included one underrepresented group, we carefully considered and selected animals that would not carry a negative stigma (Sommer & Sommer, 2008). Although some research suggests that different animals connote different genders (Sommer & Sommer), the use of animal labels does not exclude individuals of any gender identity. Our study is exploratory, and our model should not be generalized to other populations or applied in practice. However, as with any model, well-trained practitioners who convey information about temperament to caregivers do so ethically, sensitively, and with consideration for family characteristics. In other words, we suggest that the quality of the interactions between practitioners and consumers is as, if not more, important than the labels applied to the children.

Future Directions

To further support our categories, which we argue are consistent with previous studies, future researchers might conduct replications with larger, more representative samples of preschool and school-aged children. Additionally, longitudinal studies would advance our understanding of temperament categories and developmental trajectories by providing information about stability and change in children in each group. As temperament is influential throughout our lives, future research should continue previous research efforts by examining academic, behavioral, and social outcomes for specific clusters of children. Findings from such studies would aid child practitioners in identifying and treating students at risk for academic problems, delinquency, mental health issues, and poor interpersonal relationships.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our research contributes to the temperament literature by supporting the trends in previous attempts to group children by temperament. By integrating our findings with previous theoretically and empirically supported models, we provide a basis for furthering temperament research. Practitioners who work with young children certainly appreciate the importance of using “real-world” language with caregivers. We hope that the labels we assigned to our groups—koalas, penguins, dogs, bobcats, and giraffes—will serve as a starting point for linking temperament research, school-based practice, and family interactions.

References

Acar, I. H., Torquati, J. C., Raikes, H., & Rudasill, K. M. (2021). Pathways to low-income children’s self-regulation: Child temperament and the qualities of teacher–child relationships. Early Education and Development, 32(8), 1103–1121. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2020.1830465

Bair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 711–731. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015221

Barger, B., Moody, E. J., Ledbetter, C., D’Abreu, L., Hepburn, S., & Rosenberg, S. A. (2019). Temperament similarities and differences: A comparison of factor structures from the Behavioral Style Questionnaire in children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(5), 1749–1762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-03866-1

Benson, N. F., Floyd, R. G., Kranzler, J. H., Eckert, T. L., Fefer, S. A., & Morgan, G. B. (2019). Test use and assessment practices of school psychologists in the United States: Findings from the 2017 National Survey. Journal of School Psychology, 72, 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.12.004

Brannigan, R., Cannon, M., Tanskanen, A., Huttunen, M. O., Leacy, F. P., & Clarke, M. C. (2020). Childhood temperament and its association with adult psychiatric disorders in a prospective cohort study. Schizophrenia Research, 216, 229–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2019.11.055

Brown, K. M., Perez-Edgar, K., & Lunkenheimer, E. (2022). Understanding how child temperament, negative parenting, and dyadic parent-child behavioral variability interact to influence externalizing problems. Social Development, 31, 1020–1041. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12601

Buzzell, G. A., Troller-Renfree, S. V., Barker, T. V., Bowman, L. C., Chronis-Tuscano, A., Henderson, H. A., Kagan, J., Pine, D. S., & Fox, N. A. (2017). A neurobehavioral mechanism linking behaviorally inhibited temperament and later adolescent social anxiety. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56, 1097–1105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.10.007

Cappella, E., O’Connor, E. E., McCormick, M., Turbeville, A., Collins, A., & McClowry, S. G. (2015). Classwide efficacy of INSIGHTS: Observed student behaviors and teacher practices in kindergarten and first grade. Elementary School Journal, 116(2), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1086/683983

Carey, W. B. (1998). Temperament and behavior problems in the classroom. School Psychology Review, 27, 522–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1998.12085935

Carey, W. B., & McDevitt, S. C. (1995). The Carey Temperament Scales. Behavioral-Developmental Initiatives

Caspi, A., & Silva, P. A. (1995). Temperamental qualities at age three predict personality traits in young adulthood: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Child Development, 66, 486–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00885.x

Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1996). Temperament: Theory and practice. Brunner/Mazel

Dare, S. P., Owusu, R., & Asante, O. (2021). Child temperament and academic performances among kindergarteners. International Journal of Current Science Research and Review, 4(5), 333–338. https://doi.org/10.47191/ijcsrr/V4-i5-02

Doan, S., Steiner, E. D., Pandey, R., & Woo, A. (2023). Teacher well-being and intentions to leave: Findings from the 2023 State of the American Teacher Survey. RAND Corporation https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-8.html

Fleck, L., Fuchs, A., Williams, K., Moehler, E., Resch, F., Koenig, J., & Kaess, M. (2024). Child temperament as a longitudinal predictor of mother–adolescent interaction quality: Are effects independent of child and maternal mental health? European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02359-6

Flesch, R. (1948). A new reliability yardstick. Journal of Applied Psychology, 32, 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0057532

Gibbs, M. V., Reeves, D., & Cunningham, C. C. (1987). The application of temperament questionnaires to a British sample: Issues of reliability and validity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 28, 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1987.tb00652.x

Goldsmith, H. H. (1996). Studying temperament via construction of the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire. Child Development, 67, 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01730.x

Herzog, H. A., & Galvin, S. L. (1992). Animals, archetypes, and popular culture: Tales from the tabloid press. Anthrozoos, 5, 77–92. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279392787011494

Howard, M. C., & Hoffman, M. E. (2018). Variable-centered, person-centered, and person-specific approaches: Where theory meets the method. Organizational Research Methods, 21(4), 846–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117744021

Hubert, N. C., Wachs, T. D., Peters-Martin, P., & Gandour, M. J. (1982). The study of temperament: Measurement and conceptual issues. Child Development, 53, 571–600. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129176

Huelsman, T. J., Gagnon, S. G., Kidder-Ashley, P., & Griggs, M. S. (2013). Preschool temperament assessment: A quantitative assessment of the validity of Behavioral Style Questionnaire data. Early Education and Development, 25, 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2013.770636

Ingram, J. & Barbera, A. (2023, February 3). The 20 most stressful jobs. US News and World Report. https://money.usnews.com/careers/company-culture/slideshows/the-most-stressful-jobs?onepage

Jansen van Rensburg, B., Stydom, C., & Grobler, H. (2016). Parents’ understanding of temperament and preference functions of their children. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 52(3), 332–349. https://doi.org/10.15270/52-3-513

Keough, B. K. (2003). Temperament in the classroom: Understanding individual differences. Paul H Brookes.

Kincaid, P., Fishburne, R. P., Rogers, R. L., & Chissom, B. S. (1975). Derivation of new readability formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel

Lichtenstein, R., & Ecker, B. (2019). High assessment reports for children and adolescents: A consumer-responsive approach. Guilford

Longobardi, E., Spataro, P., D’Alessandro, M., & Cerutti, R. (2017). Temperament dimensions in preschool children: Links with cognitive and affective theory of mind. Early Education and Development, 28, 377–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1238673

Magdalena, S. M. (2015). Study on the temperament as a predictor of peer interactions at preschool ages. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 187(1), 663–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.123

McClowry, S. G. (1995). The Development of the School-Age Temperament Inventory. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 41(3), 271–285. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23087890.

McClowry, S. G. (2002a). The temperament profiles of school-age children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 17, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1053/jpdn.2002.30929

McClowry, S. G. (2002b). Transforming temperament profile statistics into puppets and other visual media. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 17, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1053/jpdn.2002.30933

McClowry, S., Rodriguez, E. T., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Spellmann, M. E., Carlson, A., & Snow, D. L. (2013). Teacher/student interactions and classroom behavior: The role of student temperament and gender. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 27, 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2013.796330

McClowry, S. G., Snow, D. L., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., & Rodriguez, E. T. (2010). Testing the efficacy of INSIGHTS on student disruptive behavior, classroom management, and student competence in inner city primary grades. School Mental Health, 2, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-009-9023-8

McCormick, M. P., O’Connor, E. E., Cappella, E., & McClowry, S. G. (2015). Getting a good start in school: Effects of INSIGHTS on children with high maintenance temperaments. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 30, 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.10.006

McDevitt, S. C., & Carey. W. B. (1996). Manual for the Behavioral Style Questionnaire. Behavioral-Developmental Initiatives

McDevitt, S. C., & Carey, W. B. (1978). The measurement of temperament in 3–7 year old children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19, 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1978.tb00467.x

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2020). Developmentally appropriate practice: A position statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/enhance-development

Nasvytienė, D., & Lazdauskas, T. (2021). Temperament and academic achievement in children: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology, & Education, 11, 736–757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11030053

O’Connor, E., Rodriguez, E., Cappella, E., Morris, J., & McClowry, S. (2012). Child disruptive behavior and parenting efficacy: A comparison of the effects of two models of INSIGHTS. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(5), 555–572. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21482

Prokasky, A., Rudasill, K., Molfese, V. J., Putnam, S., Garstein, M., & Rothbart, M. (2017). Identifying child temperament types using cluster analysis in three samples. Journal of Research in Personality, 67, 90–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.10.008

Pullis, M., & Cadwell, J. (1985). Temperament as a factor in the assessment of children educationally at risk. The Journal of Special Education, 19(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/002246698501900107

RAND Corporation. (2022). Teacher and principle stress running at twice the rate of general working public, hindering pandemic recovery. [Press release]. https://www.rand.org/news/press/2022/06/15.html

Richardson, K. S., Burke, K. C., Brazley, K. N., Jones, T. M., & Bottoms, B. L. (2020). Understanding African Americans’ attitudes toward nonhuman animals: Historical and psychological perspectives. Society & Animals, 31(2), 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-BJA10013

Rothbart, M. K. (2011). Becoming who we are: Temperament and personality in development. Guilford Press

Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A., Hershey, K. L., & Fisher, P. (2001). Investigations of temperament at 3–7 years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development, 72, 1394–1408. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3654394.

Rothbart, M. K., & Derryberry, D. (1981). Development of individual differences in temperament. In M. E. Lamb & A. L. Brown (Eds.), Advances in developmental psychology (pp. 37–86). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rothbart, M. K., & Mauro, J. A. (1990). Questionnaire approaches to the study of infant temperament. In J. W. Fagen & J. Colombo (Eds.), Individual differences in infancy: Reliability, stability, and prediction (pp. 411–429). Erlbaum.

Sanson, A., Hemphill, S. A., & Smart, D. (2004). Connections between temperament and social development: A review. Social Development, 13, 142–170. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-9507.2004.00261.x

Scheier, L. M., Casten, R. J., & Fullard, W. (1995). Latent-variable confirmatory factor analysis of the Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire. Journal of Adolescent Research, 10, 246–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743554895102004

MA Sealy KM Rudasill JS Barrett J Eum N Adams A Hinrichs S McClowry 2021 Temperament in the early elementary classroom: Implications for practice IntechOpen https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.96270

Sommer, R. (2008). Semantic profiles of zoos and their animals. Anthrozoös, 21(3), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303708X332044

Sommer, R., & Sommer, B. A. (2011). Zoomorphy: Animal metaphors for human personality. Anthrozoös, 24(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303711X13045914865024

Thomas, A., Chess, S., & Birch, H. G. (1968). Temperament and behavior disorders in children. New York University Press

Veziroglu-Celik, M. (2023). The moderating effect of parenting stress on temperament and social competence in early childhood. Current Psychology, 42, 27874–27887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03802-8

Viljaranta, J., Aunola, K., Mullola, S., Virkkala, J., Hirvonen, R., Pakarinen, E., & Nurmi, J.-E. (2015). Children’s temperament and academic skill development during first grade: Teachers’ interaction styles as mediators. Child Development, 86, 1191–1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12379

Walsh, G., & Zadurian, N. (2023). Exploring the links between parental attachment style, child temperament and parent-child relationship quality during adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32, 2721–2736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02447-2

Ward, J. H. (1963). Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 58, 236–244. https://doi.org/10.2307/2282967

Wu, C., Jing, B., Gong, X., & Ma, X. (2023). The zoomorphic effect: A contribution to the study of images of pedagogical agents for children’s learning in instructional videos. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39(5), 1620–1635. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12822

York, K. L., & John, O. P. (1992). The four faces of Eve: A typological analysis of women’s personality at midlife. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 494–508. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.494

Zee, M., & Roorda, D. L. (2018). Student–teacher relationships in elementary school: The unique role of shyness, anxiety, and emotional problems. Learning and Individual Differences, 67, 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.08.006

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Carolinas Consortium. This research was approved by Appalachian State University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB Reference #05–40) and was conducted in a manner consistent with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The authors have no relevant financial, non-financial, or competing interests to disclose. The research leading to these results received funding from Appalachian State University’s University Research Council (IRB Reference #05–40).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study's conception and design. Sandra Gagnon performed material preparation and data collection; Jana Maine and Timothy Huelsman performed data analysis. Jana Maine wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors commented on and edited previous versions of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maine, J., Huelsman, T.J., Gagnon, S.G. et al. A Penguin is Not a Giraffe: Categorizing Preschool Children According to Temperament. Early Childhood Educ J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-024-01696-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-024-01696-8