Abstract

Parenting styles act as a risk or a protective factor for the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Moreover, children with deficits in emotion regulation often show increased aggressive behaviors. Previous studies confirm that parenting style also contributes to the development of emotion dysregulation. The present longitudinal study aims to understand this complex interplay and analyzes emotion dysregulation as mediating variable for the relationship between parental warmth or strictness and aggressive behavior from preschool through elementary school. Additionally, parents’ educational level and their unity in parenting were considered as antecedent factors influencing parenting styles. The present path analyses are based on questionnaire data from 442 children and their families. The results show indirect effects for the associations between parenting style and aggressive behavior in preschool and elementary school via children’s emotion dysregulation. At the same time, a lower level of education and unity in parenting are more strongly associated with a strict parenting style. Children’s emotion dysregulation can be positively influenced by a warm and less strict parenting style, leading to a reduction in problems with aggressive behavior from preschool to elementary school.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The important role of parents in children’s behavior development has been undisputedly emphasized in the literature. Parents can have different parenting styles characterized by basic attitudes and behavioral patterns which significantly determine the emotional climate in their interaction with the child (Pinquart & Gerke, 2019). Two dimensions of parenting styles in particular are consistently emphasized: Parental warmth and behavior control. A warm and loving parenting style is characterized by the parents’ affection, support, and acceptance of the child’s experience and behavior (Baumrind, 1965). In contrast, behavior control describes a strict and harsh parenting style that indicates parental monitoring and controlling behavior by setting strict rules, limits, and punishments (Baumrind, 1966).

Parenting Style and Child Aggressive Behavior

Various studies have highlighted that parenting styles are strongly associated with the outcome of behavioral problems (Berthelon et al., 2020; Marcone et al., 2020). In particular, the links to aggressive behavior have been confirmed many times (Masud et al., 2019). A negative parenting style characterized by harsh discipline, along with controlling and punitive behaviors, facilitates the development of aggressive behavior in young children (Berthelon et al., 2020). These predominantly negative interactions between parents and children promote antisocial and aggressive behavior and can lead to incompetent social behaviors. Children learn and manifest negative interaction patterns which they transfer to social interactions outside the parental home (e.g., in school or preschool; Roberton et al., 2012). Thus, a strict parenting style is considered a consistent predictor of the development of children’s aggressive behavior problems (Deater-Deckard et al., 2012; Rademacher & Koglin, 2020).

Conversely, a warm and loving parenting style can reduce behavior problems in children and strengthen social-emotional resources (Denham et al., 2000; Eisenberg et al., 2005). A warm parenting style is associated with a positive and loving emotional climate in the family, which supports children to behave in a socially competent manner and to exhibit less aggressive behaviors (Rademacher & Koglin, 2020; Webster-Stratton et al., 2001). At the same time, early deficits in parental warmth are significantly related to development and maintenance of aggressive behavior problems in childhood (Boeldt et al., 2012; Rothenberg et al., 2020). Therefore, the current longitudinal study aims to examine the relationship between parenting style and aggressive behavior in more detail, including the role of emotion dysregulation in this context.

The Role of Emotion Dysregulation

In recent years, emotion dysregulation in children has become an increasing focus of research. Preceding studies were able to identify emotion dysregulation as a transdiagnostic factor for various mental disorders in children and adolescents such as depression, anxiety, aggressive behavior, and eating problems (Beauchchaine & Cicchetti, 2019; McLaughlin et al., 2011; Sheppes et al., 2015).

Emotion regulation is a broad concept and includes extrinsic and intrinsic processes and describe the adaptive process that influence the experience, intensity, duration, and expression of emotions through the use of functional regulation strategies (Aldao et al., 2010; Thompson, 1994). The term emotion dysregulation describes the deficient use of functional emotion regulation strategies and the preferred use of dysfunctional strategies (Cole et al., 1994). It refers to the inability to control and modulate emotional reactions including sadness, anger, irritability, and frustration. According to Cole and Hall (2008), emotion dysregulation is characterized by contextually inappropriate emotions which either persist for a long period of time or change abruptly. The experienced emotions interfere with appropriate behavior, and attempts to regulate them are usually ineffective.

Emotion Dysregulation and Child Aggressive Behavior

Children with deficits in emotion regulation often show increased aggressive behaviors (Ersan, 2019; Paulus et al., 2021). Emotions regulation is a crucial for children’s behavior adjustment, but when emotions are primarily dysregulated, the development of aggressive behavior problems is facilitated (Thompson, 2011). Children who show enhanced aggressive behavior in preschool are at increased risk for academic and social problems in school (Dodge et al., 2008). However, Roell and colleagues (2012) indicate that emotion regulation does not always lead directly to aggressive behavior. Different child- and environment-related factors can be part of a complex interrelationship of effects. For example, Chang and colleagues (2003) explain that parenting style influences child aggression both directly and indirectly through children’s emotion dysregulation.

Emotion Dysregulation and Parenting Style

The development of emotion dysregulation is mainly determined by the family environment. Parenting style can be named as a central aspect. Previous research indicated a relationship between parenting style and emotion dysregulation in children (Goagoses et al., 2022; Morris et al., 2017; Shaw & Starr, 2019). A strict and controlling parenting style in particular is associated with emotion dysregulation in children. (Shaw & Starr, 2019). This parenting style represents an external form of regulation by imposing strict rules and fixed limits on the children’s behavior from the outside. The recurring confrontation with strict and punishing educational measures creates an increased level of negative arousal in children (Power, 2004). As a result, children have a harder time learning appropriate regulatory strategies and tend to react with impulsive or aggressive behavior in challenging situations (Allan & Lonigan, 2014; Lonigan et al., 2017).

On the contrary, a warm parenting style is mainly associated with a higher degree of functional emotion regulation (Houltberg et al., 2012). Parents who primarily practice this parenting style, demonstrate greater support and acceptance for their children’s emotions and emotional reactions (Zhou et al., 2002). In this way, a trusting relationship can be fostered, making it easier for children to regulate themselves appropriately (Bernier et al., 2010; von Suchodoletz et al., 2011).

The Current Study

Parenting styles impact the development of aggressive behavior problems in childhood (Masud et al., 2019). Therefore, the study examines how parenting styles act as a risk or a protective factor for children’s behavioral development and provides important insights for early prevention and intervention approaches. However, understanding this relationship is complex and requires consideration of additional factors. In particular, the role of child emotion dysregulation has been considered in recent years as a key variable related to both, parenting style and aggressive behavior (Goagoges et al., 2022; Morris et al., 2017). Notably, studies mutually examining complex relationships between parenting style, emotion dysregulation, and children’s aggressive behavior are sparse.

Since aggressive behavior usually exhibits high stability (Rademacher et al., 2022), the present study aimed to longitudinally examine the impact of parenting style on the development of aggressive behavior in children from preschool to elementary school. It is hypothesized that the link between parenting style and aggressive behavior in both preschool and elementary school is mediated through children’s emotion dysregulation. Since parenting is a context-related construct, parents’ level of education and their unity in parenting styles are analyzed as antecedent factors. It is hypothesized that the predominant use of a particular parenting style is affected by parents’ level of education as the educational level can influence parents’ ideas, values, and goals about child-rearing (Davis-Kean et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2022). Moreover, parents do not always agree on their style of parenting. Mothers and fathers can act differently in parenting situations and this disagreement can in turn have a negative impact on the development of child behavior problems (Kassing et al., 2018). Therefore, the interaction of the parenting style of mother and father in terms of parental coparenting and unity in parenting is considered in the analyses.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The present study was conducted in Northern Germany in a longitudinal design using questionnaire data with two timepoints of measurement as part of a larger research project. The data were collected over a time period of three years from spring 2016 to spring 2019. At the first timepoint of measurement (T1), the participating children were in the last year of preschool before starting school. Therefore, the children and their families were recruited from 39 preschools through ad hoc sampling. Study participation was voluntary and informed consent and written parental permission were obtained. The sample includes N = 442 children (three cases with completely missing data were excluded in advance). At T1, children’s average age was M = 72.49 months (SD = 4.20, ranging from 62 to 88 months) and 214 children of the sample were female (48.42%). At the second timepoint of measurement (T2), the children were in their second year of elementary school, with a mean age of 92.77 months (SD = 4.19, ranging from 83 to 107 months). The study received a positive vote from the national school authorities and was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Oldenburg, Germany.

Around 21% of the children are themselves or have a parent who was born outside of Germany. Nearly 94% of the children speak German from birth, and just under 90% generally speak German at home in the families. Around 85% of the children live in a household with both parents, and for 80% of the children, both parents are the main parenting figures. About 27% of the mothers and nearly 28% of the fathers have a university degree, and less than 2% of the mothers and fathers have no school-leaving qualification.

Measures

For the current study, measures were collected and analyzed for (1) parenting style, (2) emotion dysregulation, (3) aggressive behavior, (4) parents’ educational level, and (5) unity in parenting.

Parenting Style

Parenting style was assessed at T1 using the German Parenting Style Inventory (Eltern-Erziehungsstil-Inventar, EEI; Satow, 2013). The parenting style scales parental warmth (e.g., “I give my children a feeling of warmth and security”) and parental strictness (e.g., “If a child does not obey an important rule, there must be consequences”) were used for the present analyses. Parental strictness refers to a punitive parenting style associated with the establishment of strict rules and consequences for non-compliance, while parental warmth characterizes a parenting style that is associated with affection, support and acceptance for the child’s experience and behavior. In a self-assessment, parents rated their parenting style on 20 items (10 items per parenting style) in a four-point item format from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.“ For the present sample, internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) is 0.81 for warmth and 0.70 for strictness.

Emotion Dysregulation and Aggressive Behavior

The Behavior Rating Scales for Children (Verhaltensskalen für das Kindergartenalter, VSK; Koglin and Petermann, 2016) were used to measure children’s level of emotion dysregulation and aggressive behavior at T1 in a parent report. The scale emotion dysregulation includes 8 items (e.g., “takes a long time to recover from anger”) and the aggressive behavior scale included 10 items (e.g., “hits other children”). Parents rated children’s behavior over the past four weeks on a four-point scale ranging from “not true” to “true”. At T2, aggressive behavior was evaluated again. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) is overall high for all three scales in the present sample (emotion dysregulation α = 0.80, aggressive behavior T1 α = . 82; aggressive behavior T2 α = 0.86).

Educational Level of Parents

The level of education was measured using an index variable, built from the sum of the highest school-leaving qualifications of mother and father (in each case from 1 for “no qualification” to 6 for “university/college”).

Unity in Parenting

Parents straightforwardly yes or no to the question of whether they agree on parenting.

Data Analysis

By running a complex path model in Mplus (version 8), direct and indirect associations of parental warmth and parental strictness with aggressive behavior in preschool and elementary school were examined. Emotion dysregulation in preschool was examined as a presumed mediator for the links between parenting and child aggressive behavior. In addition, gender was added as control variable that may impact children’s emotion dysregulation, as previous studies reported gender differences in emotion (dys)regulation. Compared to girls, boys show, for example, more dysfunctional emotion regulation strategies when experiencing negative emotions such as sadness, anxiety, and anger (Sanchis-Sanchis et al., 2020). Parents’ educational level and their unity in parenting were used as correlated control variables influencing parental warmth and strictness. Both aggressive behavior scales as outcome variables were correlated to control for the influence of prior aggression level in preschool on children’s aggressive behavior in elementary school. Cases with single missing data were estimated within the model.

Prior to analysis, all scales in the path model were z-transformed to counteract inconsistent scaling. For all paths in the model, correlations were determined in advance. Significant bivariate correlations between the assumed dependent and independent variables were not considered as a condition for the following mediation analysis (cf., Warner, 2013). According to Hayes (2018), a significant bivariate correlation is not a mandatory condition for testing a mediation model. Path analysis was performed using the bootstrap method with a bootstrap of 1000 samples (Poi, 2004). According to Mooney and Duval (1993), bootstrapping can compensate for deviations from the normal distribution. The model fit indices reported are the Chi2 value, the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). CFI and TLI values > 0.95 and RMSEA and SRMR values < 0.08 represent good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The False Discovery Rate (FDR, Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) was determined in order to control for alpha-error accumulation.

Results

The descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for all variables included in the path model are shown in Table 1. There are consistently significant relationships between the independent and dependent variables assumed in the path model, with one exception for the relationship between the educational level of parents and parental warmth (r = .089, p > .05).

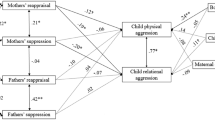

Next, Fig. 1 illustrates the predicted path model with the direct effects of the path coefficients. Significant direct effects of parental warmth (ß = − 0.280; p = .000) and parental strictness (ß = 0.132; p = .007) on children’s emotion dysregulation are found. In addition, parental strictness directly impacts children’s aggressive behavior at both time points of measurement (preschool ß = 0.108; p = .012; elementary school ß = 0.175; p = .000). Parental warmth, on the other hand, only influences child aggressive behavior at preschool directly (ß = − 0.084; p = .049), but not at elementary school (ß = − 0.075; p = .140). At the same time, parental strictness (but not parental warmth) is affected by parents’ educational level (ß = − 0.197; p = .000) and their unity in parenting (ß = 0.100; p = .041). Children’s emotion dysregulation directly predicts aggressive behavior at preschool (ß = 0.558; p = .000) and at elementary school (ß = 0.433; p = .000). in addition, gender effects children’s level of emotion dysregulation, with emotion dysregulation being more associated with boys than girls (ß = − 0.127; p = .007).

The indirect effects are shown in Table 2. Significant mediation effects of parenting via children’s emotion dysregulation exist for both preschool and elementary school aggressive behavior. Parental warmth has a positive effect on child aggressive behavior via emotion dysregulation, whereas parental strictness has a negative effect via emotion dysregulation.

A good model fit to the data is provided in Table 3. The model explains 37.3% of the variance in aggressive behavior in preschool and 26.3% in elementary school.

Discussion

The present study adds to the understanding of the complex interplay between parenting styles and aggressive behavior in childhood. To understand the mechanisms by which parenting style influence aggressive behavior, it is necessary to consider other factors that condition parenting style as well as variables that may mediate between parenting style and child behavior outcomes. In this study, parents’ educational level and their unity in parenting were considered as antecedent factors that have an influence on parenting style. A complex path model was created in which the children’s emotion dysregulation was included as a mediating variable between parenting style and aggressive behavior in both preschool and elementary school.

Direct Effects

The study was conducted in a longitudinal design allowing us to draw conclusions about the extensive influence of parenting (and its antecedent factors) and children’s emotion dysregulation on aggressive behavior problems from preschool to elementary school. Interestingly, only parental strictness has a direct effect on children’s aggressive behavior in both preschool and elementary school. According to the results, a strict parenting style promotes aggressive behavior problems over the time period from preschool to elementary school. At the same time, a strict parenting style leads to increased dysregulation of emotions. As already demonstrated by previous studies, a strict parenting style leads to increased negative interactions between parents and children, manifesting negative patterns of interaction in children, and transferring them to other contexts such as social interaction in preschool or school (Chang et al., 2003; Roberton et al., 2012). Harsh discipline, controlling, and punitive behavior on the part of the parents characterize an external form of regulation that create an increased level of negative arousal (Power, 2004). As a consequence, children might learn less about how to functionally regulate their emotions, and react with more impulsive and aggressive behaviors (Lonigan et al., 2017).

In addition, the educational level of the parents negatively effects the practice of a strict parenting style. The results suggest that a lower level of education is more strongly associated with strict parenting. At the same time, the educational level of the parents positively correlates with parents’ unity in parenting style. When parents describe themselves as united in their preferred use of a parenting style, this shows a small, but significant positive effect on strictness. The negative effect of strictness on aggressive behavior in preschool and elementary school is favored when both parents use strict parenting methods.

In contrast to parental strictness, the predictive power of a warm parenting style for aggressive behavior at preschool age is only small and these effects do not persist until school age. The results may suggest that parental warmth can be a protective factor at preschool age (even in dysregulated children), but no longer at elementary school age. With increasing age, external control seems to have a more important impact on children’s behavior development.

A significant negative effect was found from parenting style on emotion dysregulation. Accordingly, a warm and loving parenting style is associated with fewer deficits in emotion regulation. At the same time, little parental warmth leads to more dysregulated children, which increases aggressive behavior in preschool and elementary school. These findings are in line with previous findings, showing that a warm parenting style is associated with higher degrees of functional emotion regulation (Bernier et al., 2010; Houltberg et al., 2012; von Suchodoletz et al., 2011).

Indirect Effects

Indirect effects were found for both warm and strict parenting styles and aggressive behavior in preschool and elementary school. In this relationship, children’s emotion dysregulation acts as a mediating variable. The results show a negative indirect effect between parental warmth and aggressive behavior at preschool and at elementary school age. In this relation, parental warmth leads to lower dysregulation, while simultaneously low levels of emotion dysregulation act as a protective factor for aggressive behavior at both timepoints of measurement. Previous research has already shown that a warm and loving parenting style promotes regulated behavior, which in turn reduces behavioral problems (Sulik et al., 2015).

For parental strictness and aggressive behavior in preschool and elementary school, a positive indirect effect via children’s emotion dysregulation was found. A strict parenting style fosters emotion dysregulation, which in turn promotes aggressive behaviors. If parents raise their children in a predominantly strict manner, increased dysregulation acts as a risk factor for children’s behavioral development in the transition from preschool to elementary school. According to Chang and colleagues (2003), children acquire negative emotion response strategies through a strict and punitive parenting style and transfer them to other contexts, resulting in incompetent social behavior and increased aggressive behaviors.

Limitations

The results of the present study should be considered alongside several limitations. We only considered parents’ educational level and parental unity as antecedent factors that have an influence on parenting style. We know from the literature that a number of factors can influence parenting, among them proximal factors such as parents’ own childhood experiences (Belsky & Jaffee, 2006), parental mental health (Blatt-Eisengart et al., 2009; Gelfand & Teti, 1990), level of parental conflict (Patterson, 2002), as well as parenting skills and/or knowledge and beliefs about parenting (Shears & Robinson, 2005; Thompson et al., 2003). Other factors might comprise distal ones, such as family or socioeconomic stressors (Kiernan & Huerta, 2008), social support (Taylor et al., 2015), or cultural influences (Bornstein & Cheah, 2006; Bornstein et al., 2011; Dettlaff & Earner, 2012; Hassan and Rousseau, 2009). Broadening our understanding of which factors may explain the emergence of warm versus strict parenting behavior, thus influencing emotion dysregulation, and the emergence of aggressive behavior, is open to future research.

For the reported analyses, mothers and fathers were asked about their predominant parenting style. This analysis was limited in that it does not take into account the family relationship type, such as same-sex or different-sex parents, live-in or separated, or divorced. Taking a more nuanced and differentiated look at the influence of parental attitudes and child behavior could be informative (see for example, Fedewa and Clark, 2009; Patterson, 2002).

Future Directions

In this study, the etiology of aggressive behavior is more likely attributable to environmental factors (including antecedent variables like parent agreeableness on managing behavior, parental attitudes towards managing behavior, etc.). From a more developmental perspective one major factor that is common in children with externalizing behaviors is the presence of underlying language-based difficulties, especially in the area of receptive language and pragmatic language (Gremillion & Martel, 2014). Additionally, many young children with such difficulties oftentimes have co-occurring cognitive difficulties (Ryder et al., 2008). With this combined, there is a higher incidence of acting out and engagement in aggressive behavior. So the etiology then is more developmental, which should additionally be considered in further studies.

Our study results provide evidence for the central importance of emotion dysregulation in the relationship between parenting style and aggressive behavior. However, only externalizing behaviors were considered as outcome variables in the current study. If the idea is pursued that emotion dysregulation is a transdiagnostic risk factor that occurs across multiple disorders, the associations with internalizing behavior problems should also be considered. Children who repeatedly fail to regulate negative emotions are more likely to experience situations as uncontrollable. These children are more exposed to unwanted feelings, which might put them at higher risk of developing depressive and anxiety symptoms (Loevaas et al., 2018).

Moreover, the present study is limited to a one-sided view of the effects between parenting style and behavior problems. However, further studies may also consider other approaches that assume reciprocal effects, according to which undesirable child behavior results in a stricter parenting style (Burke et al., 2008; Rolon-Arroyo et al., 2018). Aggressive and dysregulated behaviors may lead parents to feel compelled to curtail their warm and loving parenting style, and use more disciplinary and strict parenting measures. At the same time, Barbot and colleagues (2014) report that social-emotional skills in children can reduce parental stress and increase positive parental engagement. Bidirectional effects should be considered in further research to gain a full understanding of the origins and interplay of behavior problems and parenting style.

Besides, future research that gives more weight to information about parental consistency in anticipating and managing child behavior, especially externalized behavior and aggression, would be interesting and helpful to the filed. In relation to unity, future studies that probe the degree of agreeableness between parents regarding their management of childhood behavior relative to subsequent behavioral trajectory (Kassing et al., 2018) is also important.

In addition to family-related factors which includes parenting style, child-related factors, such as temperament also play a role in the development of aggressive behavior. Temperament is considered innate and can be expressed in high irritability, low frustration tolerance or impulsiveness (Rothbart, 2011). In order to fully present the pathogenesis of aggressive behavior, future studies should consider temperament as well as genetic aspects should also be considered.

We were able to identify far-reaching effects of parenting style in a longitudinal study from preschool through elementary school. However, it remains open and unknown how long these effects may last. In particular, the transition from childhood to adolescence is a critical period. If behavior problems occur early, they may increase in intensity and frequency during adolescence (Caspi et al., 1996). Pardini and colleagues (2008) have shown that parenting can influence the change of behavior problems in the period from 6 to 16 years. Simultaneously, Pardini and colleagues (2008) were able to emphasize the impact of behavior problems on changes in parenting behavior. Therefore, future studies should extend the longitudinal timeline.

Practical Implications

The results of our study highlight the need to foster parenting education regarding the significance of parenting style on their children’s emotion dysregulation and aggressive bahviors. This includes, in particular, raising awareness with parents as to what actions characterize a strict style of parenting and the negative effects of on children’s development Chao et al., 2006; Thomson and Carlson, 2017). As parental strictness may arise either from beliefs or lack of parenting knowledge, or from parental strain, our results can contribute to parent focused preventive measures. When educating parents about adaptive parenting behavior, according to our results, an emphasis might be put on the positive impact of parental warmth. Showing parents explicit behaviors such as committed and loving behaviors, can encourage parents to enact a warm and supportive parenting style. Simultaneously, preventive and interventive measures must increase parents’ awareness of the importance of self-regulation of emotions and the influence of early parenting behaviors.

References

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004.

Allan, N. P., & Lonigan, C. J. (2014). Exploring dimensionality of effortful control using hot and cool tasks in a sample of preschool children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 122, 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2013.11.013.

Barbot, B., Crossman, E., Hunter, S. R., Grigorenko, E. L., & Luthar, S. S. (2014). Reciprocal influences between maternal parenting and child adjustment in a high-risk population: A 5-year cross-lagged analysis of bidirectional effects. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 567–580. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000012.

Baumrind, D. (1965). Parental control and parental love. Children, 12, 230–234.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37, 887–907. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126611.

Beauchaine, T. P., & Cicchetti, D. (2019). Emotion dysregulation and emerging psychopathology: A transdiagnostic, transdisciplinary perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 31, 799–804. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419000671.

Belsky, J., & Jaffee, S. R. (2006). The multiple determinants of parenting. In D. Cicchetti, & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (pp. 38–85). John Wiley & Sons.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling for the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 57, 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x.

Bernier, A., Carlson, S. M., & Whipple, N. (2010). From external regulation to self-regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children’s executive functioning. Child Development, 81, 326–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01397.x.

Berthelon, M., Contreras, D., Kruger, D., & Palma, M. I. (2020). Harsh parenting during early childhood and child development. Economics and Human Biology, 36, 100831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2019.100831.

Blatt-Eisengart, I., Drabick, D. A., Monahan, K. C., & Steinberg, L. (2009). Sex differences in the longitudinal relations among family risk factors and childhood externalizing symptoms. Developmental Psychology, 45, 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014942.

Boeldt, D. L., Rhee, S. H., DiLalla, L. E., Mullineaux, P. Y., Schulz-Heik, R. J., Corley, R. P., & Hewitt, J. K. (2012). The association between positive parenting and externalizing behaviour. Infant and Child Development, 2, 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.764.

Bornstein, M. H., & Cheah, C. S. L. (2006). The place of “culture and parenting” in the ecological contextual perspective on developmental science. In K. H. Rubin, & O. B. Chung (Eds.), Parenting beliefs, behaviors, and parent-child relations: A cross-cultural perspective (pp. 3–33). Psychology Press.

Bornstein, M. H., Putnick, D. L., & Lansford, J. E. (2011). Parenting attributions and attitudes in cross-cultural perspective. Parenting Science and Practice, 11, 214–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2011.585568.

Burke, J. D., Pardini, D. A., & Loeber, R. (2008). Reciprocal relationships between parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 679–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9219-7.

Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Newman, D. L., & Silva, P. A. (1996). Behavioral observations at age three years predict adult psychiatric disorders: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53, 1033–1039. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009.

Chang, L., Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., & McBride-Chang, C. (2003). Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 598–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598.

Chao, P. C., Bryan, T., Burstein, K., & Ergul, C. (2006). Family-centered intervention for young children at-risk for language and behavior problems. Early Childhood Education Journal, 34, 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-005-0032-4.

Cole, P. M., & Hall, S. E. (2008). Emotion dysregulation as a risk factor for psychopathology. In T. P. Beauchaine, & S. P. Hinshaw (Eds.), Child and adolescent psychopathology (pp. 265–298). Wiley & Sons.

Cole, P. M., Michel, M. K., & Teti, L. O. (1994). The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 73–100. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166139.

Davis-Kean, P. E., Tighe, L. A., & Waters, N. E. (2021). The role of parent educational attainment in parenting and children’s development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30, 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721421993116.

Deater-Deckard, K., Wang, Z., Chen, N., & Bell, M. A. (2012). Maternal executive function, harsh parenting, and child conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 1084–1091. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02582.x.

Denham, S. A., Workman, E., Cole, P. M., Weissbrod, C., Kendziora, K. T., & Zahn-Waxler, C. (2000). Prediction of externalizing behavior problems from early to middle childhood: The role of parental socialization and emotion expression. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400001024.

Dettlaff, A. J., & Earner, I. (2012). Children of immigrants in the child welfare system: Characteristics, risk, and maltreatment. Families in Society, 93, 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.4240.

Dodge, K. A., Greenberg, M. T., Malone, P. S., & The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2008). Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Development, 79, 1907–1927. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01233.x.

Eisenberg, N., Zhou, Q., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., Fabes, R. A., & Liew, J. (2005). Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development, 76, 1055–1071. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00897.x.

Ersan, C. (2019). Physical aggression, relational aggression and anger in preschool children: The mediating role of emotion regulation. The Journal of General Psychology, 147, 18–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2019.1609897.

Fedewa, A. L., & Clark, T. P. (2009). Parent practices and home-school partnership: A differential effect for children with same-sex coupled parents? Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 5, 312–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504280903263736.

Gelfand, D. M., & Teti, D. M. (1990). The effects of maternal depression on children. Clinical Psychology Review, 10, 329–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(90)90065-I.

Goagoses, N., Bolz, T., Eilts, J., Schipper, N., Schuetz, J., & Koglin, U. (2022). Parenting dimensions / styles and emotion dysregulation in childhood and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03037-7.

Gremillion, M. L., & Martel, M. M. (2014). Merely misunderstood? Receptive, expressive, and pragmatic language in young children with disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43, 765–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.822306.

Hassan, G., & Rousseau, C. (2009). North african and latin american parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions of physical discipline and physical abuse: When dysnormativity begets exclusion. Child Welfare, 88, 5–22.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Houltberg, B. J., Henry, C. S., & Morris, A. S. (2012). Family interactions, exposure to violence, and emotion regulation: Perceptions of children and early adolescents at-risk. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 61, 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00699.x.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Kassing, F., Lochmann, J. E., & Glenn, A. L. (2018). Autonomic functioning in reactive versus proactive aggression: The influential role of inconsistens parenting. Aggressive Behavior, 44, 524–536. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21772.

Kelly, C. L., Slicker, G., & Hustedt, J. T. (2022). Family experiences, parenting behaviors, and infants’ and toddlers’ social-emotional skills. Early Childhood Education Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-022-01425-z.

Kiernan, K. E., & Huerta, M. C. (2008). Economic deprivation, maternal depression, parenting and children’s cognitive and emotional development in early childhood. British Journal of Sociology, 59, 783–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2008.00219.x.

Koglin, U., & Petermann, F. (2016). Verhaltensskalen für das Kindergartenalter. [Behavior Rating Scales for Children]. Hogrefe.

Loevaas, M. E. S., Sund, A. M., Patras, J., Martinsen, K., Hjemdal, O., Neumer, S. P., & Reinfjell, T. (2018). Emotion regulation and its relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression in children aged 8–12 years: Does parental gender play a differentiating role? BMC Psychology, 6, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0255-y.

Lonigan, C. J., Spiegel, J. A., Goodrich, J. M., Morris, B. M., Osborne, C. M., Lerner, M. D., & Phillips, B. M. (2017). Does preschool self-regulation predict later behavior problems in general or specific problem behaviors? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 1491–1502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0260-7.

Marcone, R., Affuso, G., & Borrone, A. (2020). Parenting styles and children’s internalizing-externalizing behavior: The mediating role of behavior regulation. Current Psychology, 39, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9757-7.

Masud, H., Ahmad, M. S., Cho, K. W., & Fakhr, Z. (2019). Parenting styles and aggression among young adolescents: A systematic review of literature. Community Mental Health Journal, 55, 1015–1030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00400-0.

McLaughlin, K. A., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Mennin, D. S., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2011). Emotion dysregulation and adolescent psychopathology: A prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.003.

Mooney, C. Z., & Duval, R. D. (1993). Bootstrapping: A nonparametric approach to statistical inference. Sage.

Morris, A. S., Criss, M. M., Silk, J. S., & Houltberg, B. J. (2017). The impact of parenting on emotion regulation during childhood and adolescence. Child Development Perspectives, 11, 233–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12238.

Pardini, D. A., Fite, P. J., & Burke, J. D. (2008). Bidirectional associations between parenting practices and conduct problems in boys from childhood to adolescence: The moderating effect of age and african-american ethnicity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 647–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9162-z.

Patterson, G. R. (2002). The early development of coercive family process. In J. B. Reid, G. R. Patterson, & J. Snyder (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention (pp. 25–44). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10468-002.

Paulus, F. W., Ohmann, S., Moehler, E., Plener, P., & Popow, C. (2021). Emotion dysregulation in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychiatry,12, 628252. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.628252.

Pinquart, M., & Gerke, D. C. (2019). Associations of parenting styles with self-esteem in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(8), 2017–2035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01417-5.

Poi, B. P. (2004). From the help desk: Some bootstrapping techniques. Stata Journal, 4, 312–328.

Power, T. G. (2004). Stress and coping in childhood: The parents’ role. Parenting: Science and Practice, 4, 271–317. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327922par0404_1.

Rademacher, A., & Koglin, U. (2020). Self-regulation as a mediator for the relationship between parenting and the development of behavior problems and social-emotional competences in elementary school children. Kindheit und Entwicklung, 29, 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1026/0942-5403/a000297.

Rademacher, A., Zumbach, J., & Koglin, U. (2022). Cross-lagged effects of self-regulation skills and behavior problems in the transition from preschool to elementary school. Early Child Development and Care, 192, 631–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1784891.

Roberton, T., Daffern, M., & Bucks, R. S. (2012). Emotion regulation and aggression. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17, 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.09.006.

Roell, J., Koglin, U., & Petermann, F. (2012). Emotion regulation and child aggression: Longitudinal associations. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 43, 909–923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0303-4.

Rolon-Arroyo, B., Arnold, D. H., Breaux, R. P., & Harvey, E. A. (2018). Reciprocal relations between parenting behaviors and conduct disorder symptoms in preschool children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 49, 786–799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-018-0794-8.

Rothbart, M. K. (2011). Becoming who we are. Temperament and personality in development. Guilford Press.

Rothenberg, W. A., Lansford, J. E., Bacchini, D., Bornstein, M. H., Chang, L., & Al-Hassan, S. M. (2020). Cross-cultural effects of parent warmth and control on aggression and rule-breaking from ages 8 to 13. Aggressive Behavior, 46, 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21892.

Ryder, N., Leinonen, E., & Schulz, J. (2008). Cognitive approach to assessing pragmatic language comprehension in children with specific language impairment. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 43, 427–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820701633207.

Sanchis-Sanchis, A., Grau, M. D., Moliner, A. R., & Morales-Murillo, C. P. (2020). Effects of age and gender in emotion regulation of children and adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 946. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00946.

Satow, L. (2013). Eltern-Erziehungsstil-Inventar (EEI): Test- und Skalendokumentation [Parenting Style Inventory]. Available at http://www.drsatow.de.

Shaw, Z. A., & Starr, L. R. (2019). Intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation: The role of authoritarian parenting style and family chronic stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 3508–3518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01534-1.

Shears, J., & Robinson, J. (2005). Fathering attitudes and practices: Influences on children’s development. Child Care in Practice, 11, 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357527042000332808.

Sheppes, G., Suri, G., & Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 379–405. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112739.

Sulik, M. J., Blair, C., Mills-Koonce, R., Berry, D., Greenberg, M., & Family Life Project Investigators. (2015). Early parenting and the development of externalizing behavior problems: Longitudinal mediation through children’s executive function. Child Development, 86, 1588–1603. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12386.

Taylor, Z. E., Conger, R. D., Robins, R. W., & Widaman, K. F. (2015). Parenting practices and perceived social support: Longitudinal relations with the social competence of mexican-origin children. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 3, 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000038.

Thank you for the valuable comments to improve the manuscript. We have tried to incorporate all comments as best we could.

Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of a definition. Monographs for the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 25–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166137.

Thompson, R. A. (2011). Emotion and emotion regulation: Two sides of the developing coin. Emotion Review, 3, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073910380969.

Thompson, A., Hollis, C., & Dagger, D. (2003). Authoritarian parenting attitudes as a risk for conduct problems: Results from a British National Cohort Study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 12, 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-003-0324-4.

Thomson, R. N., & Carlson, J. S. (2017). A pilot study of a self-administered parent training intervention for building preschoolers’ social–emotional competence. Early Childhood Education Jounral, 45, 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0798-6.

von Suchodoletz, A., Trommsdorff, G., & Heikamp, T. (2011). Linking maternal warmth and responsiveness to children’s self-regulation. Social Development, 20, 486–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00588.x.

Warner, R. M. (2013). Applied statistics: From bivariate through multivariate techniques (2nd ed.). Sage.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Hammond, M. (2001). Preventing conduct problems, promoting social competence: A parent and teacher training partnership in Head Start. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_2.

Zhou, Q., Eisenberg, N., Losoya, S. H., Fabes, R. A., Reiser, M., Guthrie, I. K., & Shepard, S. A. (2002). The relations of parental warmth and positive expressiveness to children’s empathy-related responding and social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development, 73, 893–915. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.0044.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rademacher, A., Zumbach, J. & Koglin, U. Parenting Style and Child Aggressive Behavior from Preschool to Elementary School: The Mediating Effect of Emotion Dysregulation. Early Childhood Educ J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01560-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01560-1