Abstract

To determine regional differences in the prevalence of overall physical health, overall mental health, and serious psychological distress (SPD). Data from the 2004 to 2016 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey were used for weighted analysis across region. Relationship modifiers considered were sociodemographic factors, health factors, and measures of health expenditures. A higher burden ratio of health care expenditures is negatively associated with health outcomes, across all US regions and insurance. Compared to 2004 values, SPD, overall physical health, and mental health are significantly improved after 2014. This research supports the whole health paradigm, indicating that overall mental and physical health are closely related. The burden of health care costs is an important consideration and related to overall health outcomes, regardless of insurance status or region. These considerations are likely increasingly important to consider with recent global events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental health is an important aspect of overall wellbeing and general health (Herman-Stahl et al., 2007; McGinty et al., 2020). Diagnosed mental illnesses have been studied extensively, however, serious psychological distress (SPD), also known as non-specific psychological distress, has not (Centers for Disease Control, 2011). Although SPD is not indicative of a specific mental illness, it is associated with anxiety and mood disorders (Andrews & Slade, 2001; Colton & Manderscheid, 2006; Herman-Stahl et al., 2007; Kessler et al., 2002; Pratt, 2009) and is also highly associated with adverse health behaviors, such as smoking, substance abuse, and physical inactivity (Mental Health By the Numbers, NAMI; Mojtabai, 2005; Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administartion, 2013). SPD has further been observed to be associated with younger age, lower income, unemployment, disabilities, poor physical health, and chronic conditions (Davison et al., 2020).

Previous research investigating physical health, mental health, and SPD, compared cultural and structural differences between countries, reporting that poor mental health tends to be more prevalent in the United States (US) compared to Europe (Weissman et al., 2016). Although the overall health benefits of physical activity are well known (Kessler et al., 2005; McGuire et al., 2009; Okoro et al., 2014), those with chronic physical conditions and disabilities frequently experience SPD, resulting in an increased risk for adverse health outcomes and premature death (Andrews & Slade, 2001; Centers for Disease Control, 2011; Kessler et al., 2002). In Shi et al. 2008, adults with three or more chronic conditions were six times as likely to have reported SPD (Shih & Simon, 2008).

An emerging body of literature suggests that geography influences mental health (Kim et al., 2013). Regional differences in overall mental health have been studied in several countries (Bhavsar et al., 2014; Lewis & Booth, 1992) and it has been suggested that geographic areas with stressful environments are associated with mental illness (Martino et al., 2019; Philo, 2005). Physical activity has been considered across regions (Martin et al., 2005), but to the authors’ knowledge, no research has explicitly considered regional differences in overall physical health. When considering regional differences in SPD, most studies compare rural–urban differences of SPD and their results indicate a higher likelihood of SPD in urban residents compared to rural residents, even when adjustments for sociodemographic characteristics are considered (Dhingra et al., 2009). Serious psychological distress has been studied across sex, age, race, ethnicity, and other demographic characteristics, such as education (Dallo et al., 2013; Olfson et al., 2019; Weissman et al., 2020). However, regional differences and variations in serious psychological distress and mental health in the US have not been well elucidated (Dhingra et al., 2009). This study aims to quantify regional relationships for serious psychological distress, overall mental health, and overall physical health.

Methods

Data

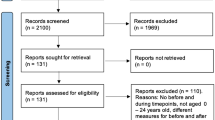

This study utilizes the 2004–2016 US Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) public use data, composed of 258,321 individuals of ages 18–64; participants are sampled from the previous years’ National Health Interview Survey. MEPS collects data through an overlapping panel design, in which participants in each panel are interviewed 5 times, or in rounds, over about 2.5 years. In any given calendar year, two panels will be participating in the survey. From MEPS person-round files, demographic characteristics and utilization of health-related services were collected; these include age group (18–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, 55–64 years old), race (white, black, other), ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic), education (< high school degree, high school, bachelor, post graduate degree), marital status (divorced, married, never married, separated, widowed), region of the US (Midwest, Northeast, South, West), cost burden (burden ratio < 10%, burden ratio ≥ 10%), whether they lacked health insurance for the current year, and type of health care insurance (any private insurance—includes TriCare and ChampVA, public only insurance—Medicare and/or Medicaid/SCHIP, or uninsured) (IPUMS MEPS). Respondents with a combination of private and public insurance were considered privately insured.

Assessments

Serious psychological distress (SPD)—One of the measures to describe SPD is the Kessler 6, or K6, which considers population-based measures to estimate SPD (Dallo et al., 2013; Okoro et al., 2009; Pratt et al., 2007; Pratt, 2009). The K6 was developed using Item Response Theory methods that capture self-reported feelings (Fraley et al., 2000; Tomitaka et al., 2017). In this six-item, psychological screening instrument, the frequency of SPD within a particular reference period is measured, ranging from “none of the time” coded zero to “all of the time” coded four, corresponding to a final range of scores from 0 to 24. Summed scores greater than 13 were used to identify those with serious psychological distress (Pratt, 2009).

Physical Health—The SF12v2 physical component summary was used to measure overall physical health. Scores range from 0 to100, where increased scores indicate better health (MEPS, 2016).

Mental Health—The SF12v2 mental health component summary was used to measure overall mental health. Scores range from 0 to100, where increased scores indicate better health (MEPS, 2016).

Total Household Income—Reported income in US dollars. Negative or zero income was adjusted to equal one hundred dollars for analysis (Banthin & Bernard, 2006).

Burden Ratio—This describes the ratio of health expenditures to income. The total amount of health care expenditures was defined as the total amount of expenditures related to prescription medicines and health care utilization, in US dollars. The burden ratio was calculated by dividing this amount by the total household income, as previously defined. Burden ratios exceeding 10% were considered financially burdened (Kielb et al., 2017).

Adjustments

Pooling health care expenditures or costs and income from 2004 to 2016 requires adjusting for inflation to remove the impact of economic growth. All health care related expenditures and costs (prescription medicine costs, health care utilization—office visits, copays, etc.) and income were inflation adjusted to 2016 dollars using the medical component of the Personal Health Care (PHC) index and using the Consumer Price Index (CPI), respectively ().

Statistical Analyses

The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) collects data from a nationally representative subsample of households obtained through a complex sample design involving stratification, clustering, and multistage sampling. These probabilities of selection, the longitudinal, panel nature of the survey, along with adjustments for non-response and post-stratification, are reflected in the provided sample weights. All statistical methods and analyses were conducted using the suggested weighting methods from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), to avoid bias. These weighted methods adjust for clustering at all levels, including family clustering (Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Computing Standard Errors for MEPS Estimates).

Data were combined and summarized using weighted descriptive statistics, such as mean and standard errors for continuous characteristics, and percent and standard errors for categorical characteristics. Differences in mean outcome scores or frequencies across demographic and health care utilization were tested using weighted Chi-square tests for categorical variables and weighted ANOVAs or independent t-tests for continuous variables. Weighted linear regression models were separately built to assess multivariable relationships for overall mental health and overall physical health, with survey respondent demographic information, region, and interactions between burden ratio, region, and insurance status. Using weighted multiple logistic regression considering demographic information, region, and interactions between burden ratio, region, and insurance status, analogous models for SPD were also built (Katon & Unützer, 2013; Mechanic & Olfson, 2016; Pratt, 2009). Interactions were included to test the hypothesis that regional relationships may be influenced by insurance status and burden ratios, as there are potential regional differences in health care expansion activities (Hibbard & Greene, 2013; Thomas et al., 2017).

Results

Higher percentages of the younger age groups, Hispanic ethnicity, and uninsured were observed in the West region compared to the other regions. In the Northeast region, higher percentages of people who are older (55–64) and those with public insurance were observed. The West region has a larger proportion (13.77%) of Other race while the South region has a larger proportion (19.31%) of Black race compared to the other regions. The proportions of low burden ratio (i.e. burden ratio < 10%) are similar across the regions. For assessments of serious psychological distress, overall mental and physical health, there is no appreciable difference across the regions.

Serious Psychological Distress (SPD)

Nearly all variables in the multivariable logistic regression model were associated with SPD (Table 1). Interestingly, compared to those 18–25 years old, those aged 46–55 had the highest odds of SPD compared to the other age groups (OR: 2.09, 95% CI 1.88, 2.31). Blacks and Hispanics had lower odds of SPD compared to Whites and non-Hispanics (all OR < 0.71). Those who are less educated or not married had higher odds of SPD (all OR > 1.19). Notably, compared to 2004, individuals had lower odds of experiencing SPD in 2014, 2015, and 2016 (all OR < 0.76). Individuals with a total burden ratio exceeding 10% had increased odds of SPD across insurance type and regions (all OR > 1.75). Specifically, the odds of SPD of the uninsured with a total burden ratio exceeding 10% was higher than the odds for those with any other type of insurance (OR 4.36, 95% CI 3.71, 5.13). Regional effects were significantly associated with SPD, observed in combination with total burden ratio greater than 10% (all OR > 2.70).

Mental Health

Similar relationships to that seen for SPD were observed for overall mental health. Older age and not being married were associated with decreased overall mental health (Table 2). However, being more educated, non-white, and Hispanic were associated with better overall mental health. Interestingly, the association with improved overall mental health increased more than two-fold after 2013 compared to 2004 levels, all else the same. A burden ratio greater than 10% was associated with decreased overall mental health across insurance types. Regional effects were significantly associated with decreased overall mental health, but only in combination with a burden ratio greater than 10% (all coefficient estimates < 3.69 and significant).

Physical Health

Aging, non-white race, and being divorced, separated, or widowed was associated with decreased physical health (Table 3). However, higher education was associated with increased physical health. Similar to trends observed for mental health, regional relationships with overall physical health were only observed in combination with increased burden ratio (all significant with estimated coefficients < 4.92). In addition, a burden ratio greater than 10% was associated with decreased overall physical health, across insurance types. Significant improvement in overall physical health was observed after 2014, compared to 2004 levels.

Discussions

In this study, small improvements in all health outcomes (overall mental health, overall physical health, and SPD) were observed after 2014, which could be due to the implementation and the expansion of Affordable Care Act, as suggested by other researchers (IPUMS MEPS; Weissman et al., 2020). Our results also indicate that aging, non-Hispanic ethnicity, and lower education are negatively associated with all health outcomes, overall physical health, overall mental health, and SPD. Being married is positively associated with improved physical health, mental health, and lower rates of SPD; being single is positively associated with improved overall physical health. People who identify as non-White have better overall mental health and lower SPD than Whites. These demographic findings are consistent with what has been previously observed, although Hispanics have been previously identified as having high psychological distress (Adams & Boscarino, 2005; Alegría et al., 2002; Dismuke & Egede, 2011; McGinty et al., 2020; McGuire & Miranda, 2008).

The main finding of our research, which we believe is noteworthy, is that regional associations were only observed in combination with a higher burden ratio of health care expenditures and that these are negatively associated with health outcomes. Similarly, insurance type, in combination with a higher burden ratio of health care expenditures, was largely associated with negative health outcomes (SPD, overall mental health, and overall physical health). This suggests that generally, greater financial burden of health care can decrease overall health, any way that it is measured (Banthin & Bernard, 2006).

Of patients that see primary care providers, the literature suggests that about 20–25% are experiencing mental health concerns, with anxiety, depression, alcohol and substance abuse disorders ranking at the top (Katon & Unützer, 2013). These rates could be twice as high for those that are uninsured or have Medicaid insurance. Mental distress during the COVID 19 pandemic is rising due to increasing anxiety related to maintaining physical health and mental wellness, job losses (with corresponding loss of health insurance), and overall financial well-being. There has been a reported more-than-threefold increase in the percentage of US adults who reported symptoms of psychological distress—from 3.9 percent in 2018 to 13.6 percent in April 2020. When considering adults ages 18–29 this increased from 3.7 percent in 2018 to 24 percent in 2020 (McGinty et al., 2020). This pandemic has exacerbated known areas of weakness for health care but opportunities to address health as a whole are being revealed which equally emphasize the importance of both physical and mental health (Blundell et al., 2020). Specifically, screening, promotion of self-care, exercise and physical health interventions, and telehealth care have increased in both availability and utilization, in recent months (Holingue et al., 2020).

Limitations of this work are related to the limited longitudinal nature of the MEPS survey, the self-reported nature of the data, and the surveyed population which are chosen to be representative of the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population, which may limit generalizability. In addition, expenditures included in the study may not be complete and although adjusted for inflation, some bias related to year of data collected may still exist. Although self-reported data are used frequently in health care research and clinical care, bias from self-reported data may be present.

Even more important since the COVID-19 pandemic and the reality of the ever-shifting “new normal”, this research supports the whole health paradigm, indicating that overall mental health and physical health are closely related. In particular, the burden of health care costs is an important consideration, regardless of insurance status or region, perhaps even more so with recent global events.

References

Adams, R. E., & Boscarino, J. A. (2005). Differences in mental health outcomes among Whites, African Americans, and Hispanics following a community disaster. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes., 68(3), 250–265. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2005.68.3.250

Alegría, M., Canino, G., Ríos, R., Vera, M., Calderón, J., Rusch, D., & Ortega, A. N. (2002). Mental health care for latinos: inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and Non-Latino Whites. Psychiatric Services, 53(12), 1547–1555. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547

Andrews, G., & Slade, T. (2001). Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health., 25(6), 494–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00310.x

Banthin, J. S., & Bernard, D. M. (2006). Changes in financial burdens for health care: national estimates for the population younger than 65 years, 1996 to 2003. JAMA, 296(22), 2712–2719. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.22.2712

Bhavsar, V., Schofield, P., Das-Munshi, J., & Henderson, C. (2019). Regional differences in mental health stigma—analysis of nationally representative data from the Health Survey for England, 2014. PLoS ONE, 14(1), e0210834. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210834

Blundell, R., Costa Dias, M., Joyce, R., & Xu, X. (2020). COVID-19 and Inequalities*. Fiscal Studies, 41(2), 291–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5890.12232

Centers for disease control. mental illness surveillance among adults in the United States. Published online September 2, 2011.

Colton, C. W., & Manderscheid, R. W. (2006). Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventing Chronic Disease, 3(2), A42.

Dallo, F. J., Kindratt, T. B., & Snell, T. (2013). Serious psychological distress among non-Hispanic whites in the United States: The importance of nativity status and region of birth. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(12), 1923–1930. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0703-1

Davison, K. M., Lung, Y., Lin, S. L., Tong, H., Kobayashi, K. M., & Fuller-Thomson, E. (2020). Psychological distress in older adults linked to immigrant status, dietary intake, and physical health conditions in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 526–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.024

Dhingra, S. S., Strine, T. W., Holt, J. B., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). Rural-urban variations in psychological distress: Findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2007. International Journal of Public Health, 54(S1), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0002-5

Dismuke, C. E., & Egede, L. E. (2011). Association of serious psychological distress with health services expenditures and utilization in a national sample of US adults. General Hospital Psychiatry., 33(4), 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.03.014

Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology., 78(2), 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350

Herman-Stahl, M., Ashley, O. S., Penne, M. A., Bauman, K. E., Weitzenkamp, D., Aldridge, M., & Gfroerer, J. C. (2007). Serious psychological distress among parenting and nonparenting adults. American Journal of Public Health, 97(12), 2222–2229. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.081109

Hibbard, J., & Greene, J. (2013). What the evidence shows about patient activation: Better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on cost. Health Affairs, 32(2), 207.

Holingue, C., Badillo-Goicoechea, E., Riehm, K. E., Veldhuis, C. B., Thrul, J., Johnson, R. M., Fallin, M. D., Kreuter, F., Stuart, E. A., & Kalb, L. G. (2020). Mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic among US adults without a pre-existing mental health condition: Findings from American trend panel survey. Preventive Medicine., 139, 106231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106231

IPUMS MEPS. Accessed March 5, 2019. https://meps.ipums.org/meps/userNotes_expenditures.shtml

Katon, W. J., & Unützer, J. (2013). Health reform and the Affordable Care Act: The importance of mental health treatment to achieving the triple aim. Journal of Psychosomatic Research., 74(6), 533–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.04.005

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006074

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

Kielb, E. S., Rhyan, C. N., & Lee, J. A. (2017). Comparing health care financial burden with an alternative measure of unaffordability. INQUIRY: the Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing., 54, 004695801773296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958017732960

Kim, G., Parton, J. M., DeCoster, J., Bryant, A. N., Ford, K. L., & Parmelee, P. A. (2013). Regional variation of racial disparities in mental health service use among older adults. The Gerontologist, 53(4), 618–626. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns107

Lewis, G., & Booth, M. (1992). Regional differences in mental health in Great Britain. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 46(6), 608. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.46.6.608

Martin, S. L., Kirkner, G. J., Mayo, K., Matthews, C. E., Durstine, J. L., & Hebert, J. R. (2005). Urban, rural, and regional variations in physical activity. The Journal of Rural Health., 21(3), 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00089.x

Martino, S. C., Mathews, M., Agniel, D., Orr, N., Wilson-Frederick, S., Ng, J. H., Ormson, A. E., & Elliott, M. N. (2019). National racial/ethnic and geographic disparities in experiences with health care among adult Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Services Research, 54, 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13106

McGinty, E. E., Presskreischer, R., Han, H., & Barry, C. L. (2020). Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA, 324(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.9740

McGuire, L. C., Strine, T. W., Vachirasudlekha, S., Anderson, L. A., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). Modifiable characteristics of a healthy lifestyle and chronic health conditions in older adults with or without serious psychological distress, 2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. International Journal of Public Health, 54(S1), 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0011-4

McGuire, T., & Miranda, J. (2008). New evidence regarding racial and ethnic disparities in mental health: Policy implications. Health Affairs, 27(2), 393.

Mechanic, D., & Olfson, M. (2016). The relevance of the affordable care act for improving mental health care. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology., 12(1), 515–542. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-092936

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Computing Standard Errors for MEPS Estimates. Accessed March 5, 2019. https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/standard_errors.jsp

Mental Health By the Numbers|NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness. Accessed August 24, 2018. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-By-the-Numbers

MEPS 2016 full year consolidated file. Accessed March 5, 2019. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h192/h192doc.pdf

Mojtabai, R. (2005). Trends in contacts with mental health professionals and cost barriers to mental health care among adults with significant psychological distress in the United States: 1997–2002. American Journal of Public Health., 95(11), 2009–2014. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2003.037630

National Health Statistics Group, Office of the Actuary, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Table 23 National Health Expenditures; Nominal Dollars Real Dollars Price Indexes and Annual Percent Change.xlsx. Accessed July 10, 2020. http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/Tables.zip

Okoro, C. A., Stoodt, G., Rohrer, J. E., Strine, T. W., Li, C., & Balluz, L. S. (2014). Physical activity patterns among U.S. adults with and without serious psychological distress. Public Health Reports, 129(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491412900106

Okoro, C. A., Strine, T. W., Balluz, L. S., Crews, J. E., Dhingra, S., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). Serious psychological distress among adults with and without disabilities. International Journal of Public Health., 54(1), 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-0077-z

Olfson, M., Wang, S., Wall, M., Marcus, S. C., & Blanco, C. (2019). Trends in serious psychological distress and outpatient mental health care of US adults. JAMA Psychiatry., 76(2), 152. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3550

Philo, C. (2005). The geography of mental health: An established field? Current Opinion in Psychiatry., 18(5), 585–591. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.yco.0000179502.76676.c8

Pratt, L. (2009). Serious psychological distress, as measured by the K6, and mortality. Annals of Epidemiology, 19, 202–209.

Pratt, L. A., Dey, A. N., & Cohen, A. J. (2007). Characteristics of adults with serious psychological distress as measured by the K6 scale: United States, 2001–04. Advance Data, 382, 1–18.

Shih, M., & Simon, P. A. (2008). Health-related quality of life among adults with serious psychological distress and chronic medical conditions. Quality of Life Research, 17(4), 521–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9330-9

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administartion. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Abuse and Health: Mental Health Findings. NSDUH Series H-47 HHS. 2013; Publication No. (SMA) 13-4805:136.

Thomas, K. C., Shartzer, A., Kurth, N. K., & Hall, J. P. (2017). Impact of ACA health reforms for people with mental health conditions. Psychiatric Service, 69(2), 231–234. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700044

Tomitaka, S., Kawasaki, Y., Ide, K., Akutagawa, M., Yamada, H., Yutaka, O., & Furukawa, T. A. (2017). Pattern analysis of total item score and item response of the Kessler Screening Scale for psychological distress (K6) in a nationally representative sample of US adults. PeerJ, 5, e2987. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2987

Using Appropriate price indices for expenditure comparisons. Accessed March 5, 2019. https://meps.ahrq.gov/about_meps/Price_Index.shtml

Weissman, J. D., Russell, D., Harris, R., Dixon, L., Haghighi, F., & Goodman, M. (2019). Sociodemographic risk factors for serious psychological distress among U.S. veterans: Findings from the 2016 national health interview survey. Psychiatric Quarterly, 90(3), 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-019-09651-2

Weissman, J., Russell, D., & Mann, J. J. (2020). Sociodemographic characteristics, financial worries and serious psychological distress in U.S. adults. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(4), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00519-0

Acknowledgements

This project received funding from the MU Population, Education and Health Center Small Grant Program. Support for this research at the Missouri Research Data Center is gratefully acknowledged. Any opinions and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Census Bureau, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, or the National Center for Health Statistics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by IZ, EL, and NYK. The first draft of the manuscript was written by IZ and EL and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leary, E., Zachary, I. & Kyeong, N.Y. Regional Differences in Serious Psychological Distress and Overall Physical and Mental Health. Community Ment Health J 58, 770–778 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-021-00882-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-021-00882-x