Abstract

The experience of academic stress is common during high school and can have significant negative consequences for students’ educational achievement and wellbeing. High school students frequently report heightened levels of school-related distress, particularly as they approach high-stakes assessments. Programs designed to reduce or prevent academic stress are needed, and their delivery in school settings is ideal to improve treatment access. The current review aimed to examine the effectiveness of high school-based programs in reducing or preventing academic stress. A systematic search returned 31 eligible studies across 13 countries. Programs were categorised according to intervention type, format, and facilitator. Results showed that the methodological quality of most studies was poor, and many used an inactive control group. As predicted by theories of academic stress, the strongest evidence was for programs grounded in cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT). There was evidence that both universal and targeted approaches can be beneficial. The unique implementation issues for these two formats are discussed. Most programs were delivered by psychologists and were generally effective, but almost all of these were CBT programs. A smaller proportion of programs delivered by teachers were effective. Therefore, future studies should evaluate the implementation success of programs to improve the rate of effective delivery by school staff. Overall, the field will benefit from more randomised controlled trials with comparisons to active control groups, larger sample sizes and longer-term follow-ups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Academic stress is defined as the transient experience of pressure, anxiety, or distress related to achieving academic goals [1]. Theoretically, students experience academic stress when they are concerned about their capacity to cope with academic challenges [2]. Test anxiety, which originally was narrowly defined as the fear of taking tests or exams [3], has been shown to strongly overlap with academic stress [4] and anxiety disorders [5], and as such, most of the research on academic stress has come from literature examining test anxiety. This research has consistently shown that test anxiety is comprised of two components: academic-related worry (intrusive and repetitive thoughts about failing) and emotionality (emotional distress and physiological tension) (see [6]. Models of test anxiety (e.g. [7, 8] predict that cognitive factors (such as negative self-beliefs, low self-efficacy, and appraisal of situations as threatening) and unhelpful study behaviours (such as avoidance and sabotage) are important factors in maintaining academic anxiety. Consistent with this, structural equation modelling has shown that high school students with more realistic cognitions, higher academic self-efficacy, and better coping strategies in response to stress experienced less test anxiety and performed better in their examinations [9]. A recent review of 60 studies found that similar factors were related to increased academic stress among high school students, including higher trait anxiety, worry about failure, perfectionism, avoidant coping, and lower academic confidence and resilience [4].

Addressing academic stress in school students is important given its potentially serious impact on educational attainment and wellbeing. High levels of academic stress are associated with poorer examination performance, mental wellbeing, affect, sleep, confidence, motivation, and even physical health [1, 10,11,12,13]. In samples of Australian high school students, severity and prevalence of academic stress is a cause for concern. Academic anxiety has been shown to be significantly higher for students in later high school grades relative to lower grades [14, 15], particularly when students are faced with “high-stakes” examinations at the end of high school education that are associated with entrance ranks into university courses [16,17,18,19]. National and international research has revealed that coping with school-related stress is a primary concern for high school students [20], with approximately 20% reporting very high levels of stress in the final years of high school [4, 21], which increases throughout the final year of school [21]. Taken together, this data highlights the need for interventions to target academic stress specifically in high school students who are faced with high-stakes assessments and who experience increasing levels of stress.

Academic stress interventions can be made more accessible by delivering programs in the school setting [22, 23]. School-based programs are endorsed by the school, delivered on school grounds, during class time, or as an after-school activity, and can be run in group or individual format. Universal programs are delivered to an entire class or grade (usually as part of the school curriculum) regardless of whether students are currently experiencing distress. Therefore, universal programs are sometimes referred to as a “preventative” approach. Targeted programs can be selective or indicated, which are provided to students at increased risk of developing an anxiety disorder (i.e., with particular risk factors) or to students with symptoms of distress (i.e., scoring above a cut-off on a self-report measure, or identified by school staff as distressed).

To date, previous literature reviews have not examined the effectiveness of school-based interventions to reduce academic stress in high school students. Some reviews have been conducted to evaluate mental health promotion or prevention programs (for a range of mental disorders) in schools, however they did not focus exclusively on programs designed to target academic stress [22, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. A small number of reviews have investigated the effectiveness of test anxiety/stress-management interventions for school-aged children, but none specifically in high school students [31,32,33]. Common findings across these reviews were that targeted and universal programs have both led to reduced distress, programs were most often delivered by trained professionals (but some had been successfully delivered by teachers), and programs teaching cognitive-behavioural strategies were the most studied and had the strongest evidence for reducing anxiety.

A specialised review of the literature is needed on whether programs specifically for academic-related stress can be implemented effectively in schools for high school students, as this is the peak period for academic stress. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to focus exclusively on school-based programs for academic stress (including, but not limited to, test anxiety) in high school students. The aim of the current review was to better understand which types of interventions are effective and the characteristics that may alter effectiveness. From previous literature and models of academic stress, it was hypothesised that interventions which targeted theorised and known factors contributing to heightened stress (such as negative thoughts and unhelpful coping styles) would be most likely to be effective. It is anticipated that the results from this review will assist schools to select evidence-based programs that help students better manage the demands and stresses of high school.

Method

Search Strategy

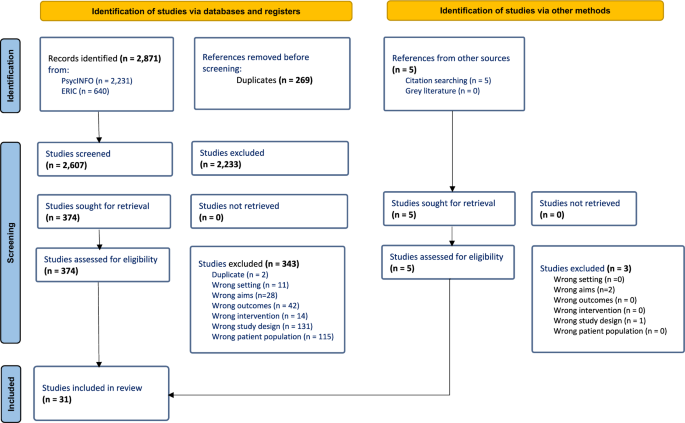

A systematic literature search was conducted using the databases, PsycINFO (American Psychological Association) 1806 to March 2023 and Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC; Institute of Education Sciences) 1966 to March 2023. Keywords were developed to capture school-based stress reduction or prevention programs for high school students: [program OR intervention OR training OR promotion] AND [stress or anxiety or academic stress or test anxiety] AND [school OR high school OR secondary school OR senior school OR school based OR classroom] AND [student* OR adolescent* OR child*] AND [target* OR universal OR at risk OR prevent* OR reduction OR reduce]. Results were limited to studies published in English peer-reviewed journals. This search returned a total of 2,871 articles.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies had to meet the following criteria to be included: (a) participants were high school students; (b) the intervention was school-based; (c) the intervention primarily aimed to reduce or prevent school-related stress or anxiety (i.e., the authors specifically stated that the intervention targeted academic or school-related stress, the authors noted details of the intervention that included reference to academic or school-related stress or the authors included a measure of academic or school-related stress pre- and post-intervention); (d) a primary outcome measure included students’ level of stress or anxiety, measured at both pre- and post-intervention; (e) the intervention group was compared statistically to a control group in a randomised controlled trial. All types of interventions were eligible (e.g., physical, psychological, educational) and the intervention could either be targeted or universal. Given that Australian high schools include grades 7 to 12, studies that reported on “middle school” students in grades 7 or above were included. Similarly, studies that included both primary and high school students were included if they reported subgroup analyses for high school students. Studies were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria, or if: (a) subgroup analyses were not reported for high school students; (b) the intervention primarily aimed to reduce or prevent non-academic stress or an anxiety disorder (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder), mood disorder, or a problem behaviour (e.g., drug use, truancy); (c) the study was a review or research protocol.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

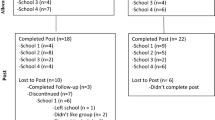

Using Covidence Systematic Review Management Software, articles were screened first by their title and abstract, and then by full text with regards to the above criteria by two authors (TJ, JB). From the database search, 31 articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in this review. An additional 5 articles sourced from reference lists were also found to be relevant, however only 2 met inclusion criteria and were included [34, 35]. Details regarding the study selection process are reported in Fig. 1, based on the PRISMA guidelines [36]. The following data was extracted for the 31 included articles, which can be found in Table 1 (targeted interventions) and Table 2 (universal interventions): (a) sample characteristics including size, age, grade, school and country; (b) intervention and comparison group; (c) program format (i.e., targeted or universal) and treatment type; (d) program facilitator and number of sessions; (e) outcome measures of distress; (f) summary of results related to stress or anxiety including effect size. Studies in which students self-selected to engage in a program (but did not require a set level of symptoms) were considered targeted interventions, as the students likely believed it would be helpful to reduce symptoms.

Methodological Quality

The quality of studies was evaluated by two authors using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2018), which includes a checklist for rating cohort studies. Based on this checklist, studies were scored according to five quality criteria; (a) explored a focused issue; (b) included an appropriate sample; (c) used outcome measures that were unlikely to be biased; (d) used an appropriate design and considered confounds; (e) analysed and interpreted results appropriately. Table 3 presents the quality ratings for each study, as meeting or not meeting the criteria (or unclear).

Results

Studies were conducted across 13 different countries: United States of America (n = 8), United Kingdom (n = 4), Australia (n = 3), Canada (n = 3), Netherlands (n = 3), China (n = 2), Switzerland (n = 2), Finland (n = 1), India (n = 1), Israel (n = 1), Jordan (n = 1), Kenya (n = 1) and Romania (n = 1). Seventeen studies evaluated a targeted intervention whereas 14 studies evaluated a universal intervention.

Outcome Measures

A wide variety of self-report measures were used to assess changes in academic stress and anxiety across studies. The most used measure included the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; [87]) which was used in six studies to measure anxiety [35, 40, 45, 58, 65, 71]. This was followed by the Spielberger Test Anxiety Inventory (TAI [57], or a variation of this measure, used in five studies [37, 53, 56, 58, 71]. The Revised Test Anxiety Scale (RTA [43], and Test Anxiety Scale for Children [60], 1978, [55] were used in four studies. Measures used less frequently were the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire (ASQ [47], the Friedben Test Anxiety Scale (FTAS [64], Revised Childrens Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS [38], Symptoms of Stress Inventory [82] and the 7-item Anxiety Scale (GAD-7 [62], which were used in two or three studies each. There were several other measures that were used in one study, as seen in Tables 1 and 2.

Intervention Format and Type

The 31 studies included in the review were categorised as targeted and universal by JB and TJ. Targeted interventions were run with a select cohort of students who typically scored above a certain cut-off indicating they were experiencing elevated symptoms or ‘vulnerability’ to anxiety or stress. Whereas universal interventions were run with all students regardless of their symptomology. Further, the primary treatment being evaluated in each study was classified into treatment type, this decision was made for each study according to the description of the intervention outlined by authors. The treatment type category, as well as a summary of treatment components, for each study can be seen in Tables 1 and 2. Overall, the majority of the 31 studies evaluated programs that included teaching students cognitive and behavioural skills (i.e., CBT, 17 studies) including traditional CBT, as well as third wave CBT. Of the remaining studies, four examined Cognitive Bias Modification, and two studies each examined Mindfulness/Meditation (including hypnosis), Systematic Desensitisation, and Social Emotional Learning. Expressive Writing and Relaxation were evaluated by one study each. The outcomes of each study will be discussed below.

Targeted Interventions

There were 16 studies identified that targeted a particular sample of participants. Nine of these studies targeted a sample of students with high-test anxiety, three targeted a sample of students with high social anxiety and one study targeted students with a combination of high test and social anxiety (see Table 1). The remaining studies targeted a self-selected sample ([40, 83], or sample with academic strengths or difficulties [39, 50], and one study did not list why they deliberately chose the sample [42].

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

CBT focuses on modifying unhelpful thoughts, beliefs and behaviours known to maintain stress or anxiety. Studies were categorised as CBT if the primary intervention targeted both behaviours and cognitions to reduce academic stress or anxiety. Eight of the targeted programs used CBT including one Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; [50], one Stress Inoculation Training (SIT [40], and one Behaviour Modification program that also included a focus on cognitions [58]. Of these eight studies, six found a significant reduction in students’ academic stress or anxiety immediately following CBT, compared to a waitlist control group with studies reporting large effect size reductions on measures of test anxiety [51, 58, 59, 72] and small effect size reductions on measures of general stress [83, 50]. Further, follow-up treatment effects were found to be sustained two months post-treatment [40] and three months post treatment [83, 58], however Van der Ploeg and Van der Ploeg-Stapert [58] did not report any statistical analyses for their finding, and no effect sizes were reported for any of the follow-up comparisons. Studies have also indicated CBT programs specifically targeted at reducing academic stress or anxiety have led to a decrease in symptoms of clinical disorders such as panic disorder and generalised anxiety disorder [72] as well as posttraumatic stress disorder [59]. The above findings have relied on self-report measures, [83] included a third-party measure of student symptoms i.e., a teacher measure, however they failed to detect a change in teacher reported emotional problems among students post treatment. The study that did not find a significant change in academic stress or anxiety for the CBT group post-treatment when compared to the waitlist control group [39] also trialled emotional freedom technique (EFT,tapping acupuncture points, and in contrast found the EFT group had a significantly greater change in anxiety pre- to post-intervention compared to waitlist control. Gaesser and Karan [39] acknowledged that their study was underpowered and that the lack of significant benefits for CBT might have been due to insufficient treatment dosage with only three treatment sessions delivered.

Systematic Desensitisation

Systematic desensitisation, which involves engaging in relaxation methods whilst visualising stressful scenarios, was analysed as a targeted approach in two studies [41, 49]. Johnson et al. [41] focused on speech anxiety within the school context, whereas Laxer and Walker [49] focused on test anxiety, however both studies yielded positive results. Johnson et al. [41] found that the systematic desensitisation group and speech practice groups both experienced a significant decrease in speech anxiety post-treatment, compared to the no-treatment control group. Laxer and Walker [49] analysed four treatment groups (i.e., systematic desensitisation, relaxation alone, simulation alone, relaxation plus simulation), and compared these four treatment groups to an active control and non-active waitlist control. They found that the students in the systematic desensitisation and relaxation alone conditions experienced a significantly greater decrease in test anxiety compared to the students in the no treatment control condition at post-treatment.

Cognitive Bias Modification

The effectiveness of a cognitive-bias modification (CBM) program was evaluated in two randomised controlled trials [37, 53]. Sud and Prabha [56] split their sample into those with high versus low test anxiety and compared the effectiveness of a three-session attention skills training (focused on modifying worry related to test anxiety) to relaxation training as well as two matched control groups. They found that high test anxiety participants in the attention skills training condition experienced a significant decrease in worry associated with test anxiety, and this was maintained at 4-week follow-up. However, there were no significant between group differences and no significant effects on state anxiety. Results from the second CBM trial were published in two papers [37, 53]. de Hullu et al. and Sportel et al.’s CBM program consisted of a 10-week (2 × per week) computer-based intervention with tasks to shift students’ attention and interpretation biases. Results from Sportel et al. [53] revealed that test anxiety or social anxiety levels of students who received CBM were not significantly lower than students in a comparison CBT program (10 group sessions), or a no-intervention control condition, at any timepoint. In fact, CBT led to significantly greater reductions in test anxiety from pre-treatment to post-treatment, as well as 6-month and 12-month follow-up compared to no-treatment control. These results suggest that CBT was more beneficial than no-treatment, whereas CBM was not. However, de Hullu et al. [37] reported that the difference in symptoms for the CBT group compared to the CBM and control group, on measures of test anxiety and social anxiety, were no longer significant at 2-year follow-up. These studies suggests that treatments focused on modifying unhelpful cognitions alone, do not appear to be more effective in treating academic related stress or anxiety.

Other Programs

Other targeted programs that reported effective in treating academic stress or anxiety, were only examined in a single study. One randomised study provided some evidence that self-hypnosis significantly reduced test anxiety among highly test anxious students, compared to no intervention, and that this effect was maintained at 6-month follow-up [54]. Further, Shen et al. [52] reported that writing about positive emotions everyday led to a significantly greater decrease in test anxiety compared to neutral writing. One further study by Kamour and Altakhayneh [42] found that treatment aimed at improving social emotional learning, i.e., developing emotional intelligence related to school, led to a decrease in maths anxiety, however the quality rating for this study was poor (see Table 2).

Control Conditions

Most (i.e., 13 out of 16) targeted studies included a no intervention or waitlist control group [37, 39,40,41, 49, 83, 50, 51, 53, 54, 58, 59, 72]. Of these 13 studies, 11 found significant between group differences in favour of the treatment group, or a significant change in symptoms for the treatment group, but no effect for the control group. Of the two studies that found no effect between groups, one implemented CBM [37] and the other CBT [40]. Six studies [37, 39, 41, 49, 50, 53] included alternative treatment groups as well as an inactive control group, and three of these compared online and face to face programs [37, 50, 53]. Of these six studies, none found a significant difference between target treatment and active control groups, although Laxer and Walker [49] did not report differences between active treatment groups as they focused on differences between treatment and inactive control groups. Three studies only included an active control group with no inactive control [42, 52, 56], and all three found significant differences in favour of the treatment compared to control group. Although, Sud and Prabha [56] did not find significant between group differences.

Universal Interventions

There were 15 studies that evaluated treatments to reduce academic stress and anxiety among a non-selected (universal) sample of students. See Table 2.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Nine of the studies evaluating universal interventions examined the effectiveness of CBT [34, 35, 45, 46, 63, 66, 70, 71]. Compared to results of studies investigating targeted CBT, studies investigating universal CBT were more mixed, with seven of the nine studies reporting a reduction in academic stress and anxiety post intervention or at follow-up [35, 45, 46, 48, 66, 70, 71], however one of these studies only reported a reduction in symptoms for students with high test anxiety [66].

Researchers have found that students who complete CBT as part of a universal treatment report lower anxiety and stress compared to control participants at post-treatment, as well as 4-week [45] and 3-month follow-up [35]. Effect size benefits were generally reported to be moderate. Further, although Lang et al. (2016, 2017 did not find a reduction in stress among students immediately following CBT, they reported a significant increase in emotion focused coping skills, and a reduction in stress relative to the control group at 6-month follow-up. Further, the effects of CBT aimed at reducing academic stress and anxiety may generalise to other psychological symptoms. Weems et al. [70] also examined test anxiety pre- to post-CBT among children exposed to Hurricane Katrina, they found a reduction in test anxiety in the treatment group compared to wait-list control. Further, Weems et al. [70] reported that PTSD symptoms within the CBT group significantly decreased, whereas those in the waitlist control group did not. However, Yahav and Cohen [71] examined the effect of CBT on test anxiety and state anxiety among Israeli Jewish and Israeli Arab students and they found that students in the CBT condition experienced a decrease in these symptoms compared to controls pre- to post-treatment. Although, the effect on test anxiety was most pronounced among Arab compared to Jewish students, possibly due to their higher reported test anxiety pre-treatment.

Other studies have been more mixed in terms of their findings regarding the effectiveness of universal CBT programs. Putwain et al. [66] found students with high test anxiety reported a reduction in test anxiety post CBT, however those with mild to low test anxiety did not. Further, Gregor et al. (2005) conducted a study evaluating the effectiveness of CBT alone, relaxation alone and a mix of CBT and relaxation, compared to a control condition. They found no significant difference between student reported anxiety pre- to post-treatment among students in these four conditions. However, they also included a teacher measure of anxiety and found that teachers rated students in the relaxation alone group as significantly less anxious compared to the CBT alone or control group. On both student and teacher measures, students in the mixed CBT and relaxation group had an increase in anxiety post-treatment, however these students started with lower anxiety ratings compared to the other groups indicating that CBT may be more beneficial for those with higher test anxiety, like findings from Yahav and Cohen [71] and Putwain et al. [66]. In line with findings from Gregor et al. (2005), Keogh et al. [34] also did not find that their CBT program decreased test anxiety, however they did report a decrease in mental ill-health among their sample following treatment compared to the control group.

Mindfulness and Meditation Programs

Mindfulness as a universal program was analysed in two studies [44, 61]. Results from these studies indicate that mindfulness/meditation interventions aimed at reducing academic stress and anxiety were no more effective at reducing stress and anxiety symptoms compared to an active control condition. Frank et al. [61] reported no significant difference between the mindfulness group and usual health education control group for symptoms of anxiety or stress pre- to post-intervention. Further, Khalsa et al. [44] compared a yoga intervention with a focus on mindfulness to usual physical education class and reported no significant difference in anxiety or stress between these groups pre- to post-treatment.

Other Programs

Four authors analysed another type of intervention among a universal sample. Although these interventions are encouraging, they were only evaluated in one study each. Stanton [67] conducted a study of imagery/hypnosis compared to a no-treatment control, he reported that the intervention group experienced a decrease in self-reported stress pre- to post treatment, which was maintained at 6-month follow-up, whereas there was no change in stress for the control group over time. Hiebert et al. [65] randomly allocated students across Grade 8 to progressive muscle relaxation or an active control group (career education class), they reported that progressive muscle relaxation led to a reduction in trait anxiety compared to the active control condition. Wang et al. [69] implemented a social emotional learning intervention over 32 sessions among a large number of Chinese students (3,694 students) and compared this to a no-intervention control condition. They found a significant reduction in learning anxiety symptoms and school dropout among students in the intervention condition compared to control at post-treatment, but this reduction was not maintained at the 6-month follow-up. Another more recent study by Venturo-Conerly et al. [68] examined a novel one-treatment session approach that targeted cognitions across three conditions i.e., growth, gratitude, value affirmation, and compared these to a control condition i.e., study skills. They found that students in the value affirmation condition reported lower anxiety compared to the control intervention two weeks post intervention, however the other interventions had no effect on anxiety relative to the control condition.

Control Conditions

Of the 15 universal studies, 12 included no intervention or waitlist control groups, whilst three studies included active control groups only [45, 65, 68]. When compared to no intervention or waitlist control groups, most studies (i.e., 9) found a significant difference between groups, or a significant reduction in symptoms among treatment groups but no reduction for control participants. The three studies that found no such differences trialled CBT [34] and Mindfulness/meditation [44, 61]. Of the 12 studies that included no intervention or waitlist control groups, two also included active control groups [35, 63], however only Szabo and Marian [35] found a significant effect between the treatment and both active and inactive control groups, in favour of the target treatment group. Of the three studies that included active control conditions only, two trialled CBT (i.e., [45, 68] and one trialled PMR (i.e., [65], and all three studies found significant between group differences.

Intervention Facilitator

In 15 of the 31 studies, programs were delivered solely by psychologists or counsellors (school staff or external), 11 of the 15 studies were targeted rather than universal samples, and 10 of the 15 studies included CBT interventions as their primary treatment. All but one of the studies that were delivered by psychologists or counsellors reported significant reductions in anxiety or stress pre- to post-intervention. However, the study by Keogh et al. [34] that did not report a reduction in test anxiety reported a reduction in mental ill-health for students in the intervention group. Teachers delivered the program exclusively in six out of the 31 studies, five of these six studies were universal rather than targeted samples, and their modality was mixed, with three of the six studies including CBT as the intervention, and the other three studies including expressive writing, social and emotional learning, and mindfulness/meditation. Two of the six studies reported change in academic anxiety or stress pre- to post-intervention and these studies included expressive writing [52] social and emotional learning [69] interventions. One study reported a significant reduction in stress for the intervention compared to control group at 6-month follow-up [46, 48], and one study reported significant reduction in test anxiety for highly test anxious students in the intervention group compared to control group [66], and both studies included a CBT based intervention. One study reported psychologists or teachers delivering CBT with a reduction in stress, and an increase in self-efficacy from pre- to post intervention for the intervention group. Professional instructors delivered a program in five studies and these programs were either CBT [39, 50, 72], mindfulness/meditation [44] or systematic desensitisation [49]. Such programs were effectively delivered to result in significant reduction in academic anxiety or stress in all but one study (i.e., mindfulness/meditation,[44]. In one study [68] lay providers delivered the program with limited success. Two studies [42, 56] did not report the facilitator of the program.

Methodological Quality

The methodological quality of studies was varied, and only 10 of the 31 studies were of high quality i.e., meeting all five criteria (see Table 3). The most common problem was that studies lacked an adequate sample, for example they may have only sampled one class or school, which limits generalisability of their results (e.g., [40, 46, 48]. Some authors did not outline their aims, hypotheses, or primary outcome measures (e.g., [39, 69], some used unvalidated measures (e.g., [50], and some did not consider potential confounds such as gender, school, timing of assessments (e.g., [44, 65]. A few studies did not report enough detail in their results, for example the significance level of changes in means (e.g., [42, 58], or adjust the p-value for the number of tests performed (e.g., [44]).

Discussion

This systematic literature review aimed to examine the effectiveness of school-based academic stress programs in high school students. The review also aimed to understand delivery characteristics that may alter program effectiveness. In general, the results suggest that CBT programs delivered as a targeted approach had the most benefit, with large effect sizes reductions in test anxiety and small effect size reductions in general stress. The effectiveness of universal programs was more mixed, with the most evidence for CBT interventions which were associated with moderate effect size benefits. Although there was some preliminary evidence for programs using other interventional methods (e.g., systematic desensitisation, expressive writing), more research is needed to establish their efficacy.

In general, there was more support for interventions that used psychologists to deliver the program. However, this result may be conflated with the theoretical underpinnings of these interventions, which were typically CBT-based. There was some evidence that teachers were able to deliver programs successfully, and while it is possible that some teacher-led programs were ineffective due to low implementation fidelity (see [26], more research is needed to examine how adequately teachers adhered to the programs.

Universal Versus Targeted Approaches

Overall, results showed that both universal and targeted approaches to delivering academic stress programs can be beneficial. This is consistent with meta-analyses finding comparable effect sizes for universal and targeted school-based programs for anxiety disorders [29]. However, careful analysis of the included studies suggests that targeted treatment may be slightly more efficacious (e.g., [71]. Considering the pros and cons of each approach along with their unique implementation issues may assist schools in choosing whether to run a universal or targeted program with their students (see [26, 29].

Universal programs have the appealing potential to help students who are already highly distressed and, at the same time, prevent distress from increasing to clinical levels in the future for other students. Not needing to screen students means less resources are required, and negative stigma is reduced (because students are not singled out). An inherent difficulty with universal programs, however, is that not all students will be distressed and require intervention. Which may be why results from randomised studies are not as strong i.e., these results are watered down as the intervention does nothing for these students because their distress is already low. Further, disengagement and drop-out may be likely for students who perceive the program to be irrelevant to them. A challenge for facilitators, then, is how to engage these students. A notable challenge is that if the program is to be facilitated by teachers, then a whole-school approach will require all school staff to be on board with the program, trained, supervised, and consistent in their delivery.

Targeted programs are usually delivered to a smaller number of students and therefore require fewer trained facilitators. As such, targeted programs can feasibly be delivered by external providers to place less demand on teachers. If time is an issue, targeted programs can be run as an after-school class, which would also be less disruptive. Some schools may choose targeted programs if they address specific difficulties that are prevalent in their student population, as opposed to universal programs that may address more general difficulties. Conversely, the targeted approach has some drawbacks. School staff may not have the expertise to identify symptoms of stress or anxiety in their students, and therefore may require more training. Moreover, teachers who facilitate targeted programs may not be adequately equipped to manage high-risk students and will likely need additional support.

Study Limitations

Conclusions drawn from the current review should be considered in light of its limitations. First, our search was limited to articles published in English, which meant most studies were conducted in developed countries. Therefore, the suitability of programs and schools’ access to resources necessary for their delivery may be different in developing countries, other international education systems or other cultures. Second, by limiting our results to studies published in peer-reviewed journals, it is possible that other publications of academic stress programs (e.g., in book chapters, school journals or educational reports) were not considered.

The overall quality of the studies included in this review was variable, with several weaknesses which limit the conclusions that can be made. Most studies compared the intervention to an inactive control (no intervention or waitlist) and so it is unclear if these interventions were more beneficial than non-specific treatment effects (Gallin & Ognibene, 2012). Only one of the targeted CBT interventions was compared to an active control group [39] and as such it is not clear whether CBT programs are better than active controls. Further, in most cases targeted intervention studies recruited participants who volunteered that they felt distressed rather than using cut-off scores to enrol only those students who had heightened symptoms. Other factors may also have created variability in the study’s results, such as the outcome measures used and the level of allocation to conditions (i.e. classes versus schools). Overall, this field of research will benefit from more high-quality studies that use random allocation, adequate sample sizes, validated measures, and comparison to active control conditions.

Future Directions

In line with theoretical models of academic stress, the findings support our hypothesis that the interventions most likely to be effective were programs that targeted known factors underlying and maintaining academic stress, namely irrational thoughts, and unhelpful study behaviours. While the CBT programs addressed some of the underlying factors, increased efficacy might come from more structured targeting of factors specific to academic stress, such as perfectionism and procrastination. Further improvements might come from integrating feedback from students or teachers. This could yield important information, such as whether certain strategies/skills are helpful, which could help to refine programs to their essential components and make them easier for teachers to deliver. Better screening tools with validated cut-offs are also needed to help school staff identify which students would benefit from targeted programs, as the targeted studies in this review were inconsistent in how they determined students with “high” stress/anxiety.

Given sufficient evidence base for CBT programs in targeting academic stress, future research should examine the implementation success in order to improve the rate of successful delivery and uptake as part of routine school activities. Implementation issues (e.g., adherence to a manual, consistency between facilitators, delivery style, and student engagement) can limit a program’s effectiveness [24]. Most of the studies included in the current review did not assess the program’s implementation success. Future researchers may do so using an implementation framework (for an example, see [79]). Some researchers have already done this for school-based CBT programs [81], physical activity programs [77, 78] and mindfulness/Yoga programs [80], however more studies are needed.

It would also be interesting to examine other factors that may influence the effectiveness of academic stress programs, such as the timing of their delivery (i.e., to students in earlier versus later grades). For example, it would be useful for schools to know if programs are more relevant/beneficial when provided to students approaching the high-stakes assessments of their final year, a period typically associated with increased distress [4, 73]. This should also include measurement and reporting of adverse events and drop-outs associated with different interventions. Furthermore, given that few studies in this review conducted a long-term follow-up, future studies should assess effectiveness over time to determine whether booster sessions are needed for students to maintain stress-management skills throughout high school.

Summary

This systematic literature review focused exclusively on school-based programs designed to reduce or prevent academic stress in high school students who are more likely to experience heightened distress due to increased academic pressures (such as high-stakes assessments). The findings showed that a variety of programs exist but more high-quality studies are needed. The best evidence was for programs grounded in cognitive-behavioural therapy, supporting theoretical understandings of the factors that maintain and exacerbate academic stress. While universal and targeted approaches are both likely to be beneficial, more research is needed to understand how the implementation success of these programs can be improved, particularly when delivered by teachers.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data is available in the published literature of the primary source. The composition of the data is available from the authors.

References

Pascoe MC, Hetrick SE, Parker AG (2020) The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. Int J Adolesc Youth 25(1):104–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1596823

Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company, New York

Spielberger CD, Vaag PR (1995) Test anxiety: a transactional process model. In: Spielberger CD, Vaag PR (eds) Test anxiety: theory, assessment and treatment (pp. 1–14). Taylor and Franchis, Washington DC. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0985

Wuthrich VM, Jagiello T, Azzi V (2020) Academic stress in the final years of school: a systematic literature review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 51:986–1015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-00981-y

King NJ, Ollendick TH, Prins PJ (2000) Test-anxious children and adolescents: Psychopathology, cognition, and psychophysiological reactivity. Behav Chang 17(3):134–142. https://doi.org/10.1375/bech.17.3.134

Putwain DW (2008) Deconstructing test anxiety. Emot Behav Diffic 13(2):141–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632750802027713

Sarason IG (1984) Stress, anxiety, and cognitive interference: reactions to tests. J Pers Soc Psychol 46(4):929. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.929

Zeidner M, Matthews G (2005) Evaluation anxiety: current theory and research. In: Elliot AJ, Dweck CS (eds) Handbook of competence and motivation. Guilford Publications, London, pp 141–163

Putwain DW (2019) An examination of the self-referent executive processing model of test anxiety: control, emotional regulation, self-handicapping, and examination performance. Eur J Psychol Educ 34(2):341–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-018-0383-z

Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bögels SM (2014) Adolescents’ sleep in low-stress and high-stress (exam) times: a prospective quasi-experiment. Behav Sleep Med 12(6):493–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2012.670675

Karatas H, Alci B, Aydin H (2013) Correlation among high school senior students’ test anxiety, academic performance and points of university entrance exam. Educ Res Rev 8(13):919

Kruger L, Wandle C, Struzziero J (2007) Coping with the stress of high stakes testing. J Appl Sch Psychol 23:109–128. https://doi.org/10.1300/j370v23n02_07

Shankar NL, Park CL (2016) Effects of stress on students’ physical and mental health and academic success. Int J Sch Educ Psychol 4(1):5–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2016.1130532

Byrne B (2000) Relationships between anxiety, fear, self-esteem, and coping strategies in adolescence. J Adolesc 35(137):201–215

Moulds JD (2003) Stress manifestation in high school students: an Australian sample. Psychol Sch 40(4):391–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10093

Einstein DA, Lovibond PF, Gaston JE (2000) Relationship between perfectionism and emotional symptoms in an adolescent sample. Aust J Psychol 52(2):89–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530008255373

Hodge GM, McCormick J, Elliott R (1997) Examination-induced distress in a public examination at the completion of secondary schooling. Br J Educ Psychol 67(2):185–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1997.tb01236.x

Robinson JA, Alexander DJ, Gradisar MS (2009) Preparing for Year 12 examinations: Predictors of psychological distress and sleep. Aust J Psychol 61(2):59–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530701867821

Smith L, Sinclair KE, Chapman ES (2002) Students’ goals, self-efficacy, self-handicapping, and negative affective responses: an Australian senior school student study. Contemp Educ Psychol 27(3):471–485. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2001.1105

Ivancic I, Perrens B, Fildes J, Perry Y, Christensen H (2014) Youth Mental Health Report, June 2014: Mission Australia and Black Dog Institute.

Wuthrich VM, Belcher J, Kilby C, Jagiello T, Lowe C (2021) Tracking stress, depression, and anxiety across the final year of secondary school: a longitudinal study. J Sch Psychol 88:18–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2021.07.004

Neil AL, Christensen H (2009) Efficacy and effectiveness of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for anxiety. Clin Psychol Rev 29(3):208–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.002

Stallard P, Skryabina E, Taylor G, Phillips R, Daniels H, Anderson R, Simpson N (2014) Classroom-based cognitive behaviour therapy (FRIENDS): a cluster randomised controlled trial to Prevent Anxiety in Children through Education in Schools (PACES). The Lancet Psychiatry 1(3):185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(14)70244-5

Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB (2011) The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev 82(1):405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Feiss R, Dolinger SB, Merritt M, Reiche E, Martin K, Yanes JA, Thomas CM, Pangelinan (2019) A systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based stress, anxiety, and depression prevention programs for adolescents. J Youth Adolesc 48:1668–1685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01085-0

O’Reilly M, Svirydzenka N, Adams S, Dogra N (2018) Review of mental health promotion interventions in schools. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 53:647–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1530-1

Rones M, Hoagwood K (2000) School-based mental health services: A research review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 3:223–241. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1026425104386

Sklad M, Diekstra R, Ritter MD, Ben J, Gravesteijn C (2012) Effectiveness of school-based universal social, emotional, and behavioral programs: do they enhance students’ development in the area of skill, behavior, and adjustment? Psychol Sch 49(9):892–909. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21641

Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, Newby JM, Christensen H (2017) School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 51:30–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.005

Zhang Q, Wang J, Neitzel A (2023) School-based mental health interventions targeting depression or anxiety: a meta-analysis of rigorous randomized controlled trials for school-aged children and adolescents. J Youth Adolesc 52:195–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01684-4

Kraag G, Zeegers MP, Kok G, Hosman C, Abu-Saad HH (2006) School programs targeting stress management in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Sch Psychol 44(6):449–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.07.001

Soares D, Woods K (2020) An international systematic literature review of test anxiety interventions 2011–2018. Pastoral Care Educ 38(4):311–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2020.1725909

Von der Embse N, Barterian J, Segool N (2013) Test anxiety interventions for children and adolescents: a systematic review of treatment studies from 2000–2010. Psychol Sch 50(1):57–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21660

Keogh E, Bond FW, Flaxman PE (2006) Improving academic performance and mental health through a stress management intervention: outcomes and mediators of change. Behav Res Ther 44(3):339–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.002

Szabo Z, Marian M (2012) Stress inoculation training in adolescents: Classroom intervention benefits. J Evid Based Psychother 12(2):175–188

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group* (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Internal Med 151(4):264–269. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

de Hullu E, Sportel BE, Nauta MH, de Jong PJ (2017) Cognitive bias modification and CBT as early interventions for adolescent social and test anxiety: two-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 55:81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.11.011

Chorpita BF, Yim L, Moffitt C, Umemoto LA, Francis SE (2000) Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: a revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behav Res Ther 38(8):835–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00130-8

Gaesser AH, Karan OC (2017) A randomized controlled comparison of emotional freedom technique and cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce adolescent anxiety: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med 23(2):102–108. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2015.0316

Hains AA, Ellmann SW (1994) Stress inoculation training as a preventative intervention for high school youths. J Cogn Psychother 8(3):219–232. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.8.3.219

Johnson T, Tyler V, Thompson R, Jones E (1971) Systematic desensitization and assertive training in the treatment of speech anxiety in middle-school students. Psychol Sch 8(3):263–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(197107)8:3%3c263::aid-pits2310080312%3e3.0.co;2-m

Kamour M, Altakhayneh B (2021) Impact of a counselling program based on social emotional learning toward reducing math anxiety in middle school students. Int J Curriculum Instruct 13(3):2026–2038

Benson J, Bandalos DL (1992) Second-order confirmatory factor analysis of the reactions to tests scale with cross-validation. Multivar Behav Res 27(3):459–487. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2703_8

Khalsa SBS, Hickey-Schultz L, Cohen D, Steiner N, Cope S (2012) Evaluation of the mental health benefits of yoga in a secondary school: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Behav Health Serv Res 39(1):80–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-011-9249-8

Kiselica MS, Baker SB, Thomas RN, Reedy S (1994) Effects of stress inoculation training on anxiety, stress, and academic performance among adolescents. J Couns Psychol 41(3):335–342. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.41.3.335

Lang C, Feldmeth AK, Brand S, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Pühse U, Gerber M (2016) Stress management in physical education class: an experiential approach to improve coping skills and reduce stress perceptions in adolescents. J Teach Phys Educ 35(2):149–158. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2015-0079

Byrne DG, Davenport SC, Mazanov J (2007) Profiles of adolescent stress: the development of the adolescent stress questionnaire (ASQ). J Adolesc 30(3):393–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.004

Lang C, Feldmeth AK, Brand S, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Pühse U, Gerber M (2017) Effects of a physical education-based coping training on adolescents’ coping skills, stress perceptions and quality of sleep. Phys Educ Sport Pedagog 22(3):213–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2016.1176130

Laxer RM, Walker K (1970) Counterconditioning versus relaxation in the desensitization of test anxiety. J Couns Psychol 17(5):431. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0029876

Puolakanaho A, Lappalainen R, Lappalainen P, Muotka JS, Hirvonen R, Eklund KM, Ahonen PS, Kiuru N (2019) Reducing stress and enhancing academic buoyancy among adolescents using a brief web-based program based on acceptance and commitment therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Youth Adolesc 48(2):287–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0973-8

Putwain DW, Pescod M (2018) Is reducing uncertain control the key to successful test anxiety intervention for secondary school students? Findings from a randomized control trial. Sch Psychol Q 33(2):283–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000228

Shen L, Yang L, Zhang J, Zhang M (2018) Benefits of expressive writing in reducing test anxiety: a randomized controlled trial in Chinese samples. PLoS ONE 13(2):e0191779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191779

Sportel BE, de Hullu E, de Jong PJ, Nauta MH (2013) Cognitive bias modification versus CBT in reducing adolescent social anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 8(5):e64355. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064355

Stanton HE (1994) Self-hypnosis: One path to reduced test anxiety. Contemp Hypn 11(1):14–18

Sarason IG, Ganzer VJ (1962) Anxiety, reinforcement, and experimental instructions in a free verbalization situation. Psychol Sci Public Interest 65(5):300. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048977

Sud A, Prabha I (1995) Test anxiety and academic performance: efficacy of cognitive/relaxation therapies. Psychol Stud 40:179–186. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-1748.2017.00001.7

Spielberger CD (1980) The test anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologist Press Inc, Palo Alto

Van Der Ploeg HM, Van Der Ploeg-Stapert JD (1986) A multifacetted behavioral group treatment for test anxiety. Psychol Rep 58(2):535–542. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1986.58.2.535

Weems CF, Scott BG, Graham RA, Banks DM, Russell JD, Taylor LK, Cannon MF, Varela RE, Scheeringa MA, Perry AM, Marina RC (2015) Fitting anxious emotion-focused intervention into the ecology of schools: results from a test anxiety program evaluation. Prev Sci 16:200–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-014-0491-1

Sarason SB, Davidson K, Lighthall F, Waite R (1958) A test anxiety scale for children. Child Dev. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126274

Frank JL, Broderick PC, Oh Y, Mitra J, Kohler K, Schussler DL, Greenberg MT (2021) The effectiveness of a teacher-delivered mindfulness-based curriculum on adolescent social-emotional and executive functioning. Mindfulness 12:1234–1251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01594-9

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10):1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Gregor A (2005) Examination anxiety: live with it, control it or make it work for you? Sch Psychol Int 26(5):617–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034305060802

Friedman IA, Bendas-Jacob O (1997) Measuring perceived test anxiety in adolescents: a self-report scale. Educ Psychol Measur 57(6):1035–1046. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164497057006012

Hiebert B, Kirby B, Jaknavorian A (1989) School based relaxation: attempting primary prevention. Can J Couns Psychother 23(3):273–287

Putwain D, Chamberlain S, Daly AL, Sadreddini S (2014) Reducing test anxiety among school-aged adolescents: a field experiment. Educ Psychol Pract 30(4):420–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2014.964392

Stanton HE (1985) The reduction of children’s school-related stress. Aust Psychol 20(2):171–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050068508256163

Venturo-Conerly KE, Osborn TL, Alemu R, Roe E, Rodriguez M, Gan J, Weisz JR (2022) Single-session interventions for adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms in Kenya: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 151:104040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2022.104040

Wang H, Chu J, Loyalka P, Xin T, Shi Y, Qu Q, Yang C (2016) Can social–emotional learning reduce school dropout in developing countries? J Policy Anal Manag 35(4):818–847. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21915

Weems CF, Taylor LK, Costa NM, Marks AB, Romano DM, Verrett SL, Brown DM (2009) Effect of a school-based test anxiety intervention in ethnic minority youth exposed to Hurricane Katrina. J Appl Dev Psychol 30(3):218–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.11.005

Yahav R, Cohen M (2008) Evaluation of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for adolescents. Int J Stress Manag 15(2):173–188. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.15.2.173

Putwain DW, von der Embse NP (2021) Cognitive–behavioral intervention for test anxiety in adolescent students: do benefits extend to school-related wellbeing and clinical anxiety. Anxiety Stress Coping 34(1):22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1800656

Lotz C, Sparfeldt JR (2017) Does test anxiety increase as the exam draws near?–Students’ state test anxiety recorded over the course of one semester. Personality Individ Differ 104:397–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.032

Johnson C, Burke C, Brinkman S, Wade T (2017) A randomized controlled evaluation of a secondary school mindfulness program for early adolescents: do we have the recipe right yet? Behav Res Ther 99:37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.09.001

Lam K, Seiden D (2020) Effects of a brief mindfulness curriculum on self-reported executive functioning and emotion regulation in Hong Kong adolescents. Mindfulness 11(3):627–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01257-w

Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven de Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J, Saw S, Buckingham WJ, Zubrick SR (2015) The mental health of children and adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Australian Government Department of Health, Canberra

Cassar S, Salmon J, Timperio A, Naylor PJ, Van Nassau F, Ayala AMC, Koorts H (2019) Adoption, implementation and sustainability of school-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour interventions in real-world settings: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 16(1):120–132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0876-4

Christian DL, Todd C, Rance J, Stratton G, Mackintosh KA, Rapport F, Brophy S (2020) Involving the headteacher in the development of school-based health interventions: a mixed-methods outcome and process evaluation using the RE-AIM framework. Plos One 15(4):e0230745. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230745

Gaglio B, Shoup JA, Glasgow RE (2013) The RE-AIM framework: a systematic review of use over time. Am J Public Health 103(6):38–46. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301299

Gould LF. Dariotis JK, Greenberg MT, Mendelson T (2016) Assessing fidelity of implementation (FOI) for school-based mindfulness and yoga interventions: a systematic review. Mindfulness 7(1):5–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0395-6

Jagiello T, Wuthrich VM, Ellis LA (2022) Implementation trial of a cognitive behavioural therapy programfor reducing student stress in the final year of secondary school. Br J Educ Psychol 92:502–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12460

Leckie MS, Thompson E (1979) Symptoms of stress inventory. Seattle, WA: University of Washington

Lowe C, Wuthrich VM (2021) Randomised controlled trial of Study Without Stress: a cognitive behavioural therapy program to reduce stress in students in the final year of high school. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 52(2):205–216. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10578-020-01099-x

Spielberger CD (1970) Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (self-evaluation questionnaire)

Spielberger CD (1973) The state-trait anxiety inventory for children (STAIC). The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene PR, Vagg PR, Jacobs AG (1983) Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory (Form Y). Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research was supported by a Medical Research Future Fund Investigator grant awarded to Viviana Wuthrich (APP1197846).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TJ and VW designed the study, TJ, JB conducted initial searches, screening and data extraction, JB and AN conducted secondary searches, screening and data extraction, KB assisted with updates to literature and creating tables. VW assisted with resolving conflicts between screeners and oversaw the whole project, All authors contributed to the writing and reviewing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was not required for this study as it used data already published in the scientific literature.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jagiello, T., Belcher, J., Neelakandan, A. et al. Academic Stress Interventions in High Schools: A Systematic Literature Review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-024-01667-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-024-01667-5