Abstract

Background

Schools provide an ideal setting for promoting healthy lifestyles in youth, but it has proven difficult to promote the adoption and implementation of evidence-based programming by school leaders. The SWITCH® (School Wellness Integration Targeting Child Health) intervention is a capacity-building process designed to help school leaders learn how to plan, implement, and sustain school wellness programs on their own.

Objective

The present study evaluates the transdisciplinary approaches used in establishing an integrated research-practice partnership with the state-wide 4-H/Extension network to support broader dissemination.

Method

The study used a mixed methods approach to evaluate the degree of engagement and motivation of 4-H leaders (N = 30) for providing ancillary support for local school wellness programming. Engagement from 4-H Staff was logged over a year-long period through tracking completion of training and ongoing engagement with aspects of SWITCH. They completed checkpoint surveys and an interview to provide perceptions of supporting school implementation of SWITCH programming. Data were analysed through Pearson bivariate correlations and constant comparative analysis.

Results

County-level 4-H staff demonstrated high engagement in SWITCH by attending training sessions and hosting structured checkpoint sessions with schools. Interview data revealed that 4-H Staff valued connections with schools and emphasized that training on SWITCH was consistent with their existing roles related to youth programming.

Conclusions

The results demonstrate the value of the sequential capacity-building process used to train 4-H Staff to facilitate school wellness programming. The transdisciplinary approaches built transferable skills and fostered relationships that directly support the broader goals of 4-H.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Evidence suggests that school wellness programming is associated with improved student preventive health behaviors and indicators of academic achievement (Biddle & Asare, 2011; Donnelly et al., 2016; Singh, Uijtdewilligen, Twisk, van Mechelen, & Chinapaw, 2012). School districts have been tasked by the USDA to establish school wellness policies and programming as part of the Final Rule requirements (United States Department of Agriculture, 2016); however, research indicates that schools find it difficult for schools to adopt and sustain evidence-based, wellness programming (Berger-Jenkins et al., 2014; Cassar et al., 2019; Friend, Flattum, Simpson, Nederhoff, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2014). Strategies and recommendations for comprehensive school wellness programs have been outlined by a number of public health agencies and researchers (Centers for Disease Control, 2014; Chen et al., 2018; Institute of Medicine, 2013) however, it is apparent that schools need support and training to use and operationalize these guidelines. A systematic review of school-based physical activity interventions (Cassar et al., 2019) documented that low school-level buy- in and capacity to plan for and implement programs were major barriers to implementation. Accordingly, to advance school wellness programming it is important to develop and test implementation strategies that can build capacity and motivation for school system change.

Through a USDA-funded project (2015-68,001-23,242), we developed and evaluated educational modules and training methods to help schools develop and implement wellness programming on their own. The SWITCH® (School Wellness Integration Targeting Child Health) intervention and training process was based on an established training and implementation model (Dzewaltowski et al., 2010; Dzewaltowski, Estabrooks, & Johnston, 2002), but adaptations and refinement were needed prior to broad dissemination efforts with the project. Effective dissemination also necessitated the development of a comprehensive web-based platform that would provide a structure for school-wellness programming efforts (Welk, Chen, Nam, & Weber, 2015). Over the course of three years, we conducted a series of implementation studies to sequentially test and refine various aspects of the implementation model (Chen et al., 2018), the web-based platform used to engage the students (McLoughlin et al., 2019), and the integrated assessment tools used to evaluate school capacity and environments (Lee et al., 2018). These studies collectively document the feasibility and utility of the capacity-building process for schools. However, a critical step in the broader dissemination process was to also build capacity in the training hubs that would serve and support schools across the state (Brownson, Eyler, Harris, Moore, & Tabak, 2018; Kreuter & Wang, 2015).

A mutually beneficial partnership evolved with the 4-H Youth Development program (managed through the Iowa State University-based Extension and Outreach program) to facilitate the dissemination of SWITCH across the state. The mission of 4-H ("Empowers youth to reach their full potential through youth-adult partnerships and research-based experiences”) was a natural fit for SWITCH since 4-H Extension already supported a specific line of healthy living initiatives given that this is a national mandate by their headquarters (4-H,n.d.). Some examples of ongoing 4-H programs within the state of Iowa include Healthy Living Ambassadors, Connecting Learning and Living, and Wellness Warrior Challenge (Iowa 4-H-H Extension,n.d.), all of which are run by the state 4-H Extension office and county-level staff across the state. The emphasis on positive youth development and family engagement in 4-H was also consistent with goals of SWITCH which emphasize working through schools to also reach the home environment. Most importantly, the 4-H program can provide localized support since there are County Youth Coordinators (CYC) in each of the 99 counties trained to promote and lead 4-H programming. The county-based 4-H network is coordinated through a team of Youth Program Specialists (YPS) on a regional level and by state staff affiliated with the University so communication channels were already established for this partnership. Although the Cooperative Extension system is well positioned to support public health programming (Dwyer et al., 2017), a key consideration is that the county-based 4-H Staff are supervised and paid by their local County Extension Council and not by the state or through the University. Therefore, the degree of engagement within a county is contingent on how programming fits with each county’s needs, interests, and resources. To build capacity for the broader dissemination through 4-H it is therefore critical to be responsive to the needs and interests of stakeholders in this distributed network.

A transdisciplinary, capacity-building approach was used to promote interest and engagement in SWITCH by regional and county 4-H leaders over a two to three-year period. Transdisciplinarity in this context captures the synergies and reciprocal relationships between the university-based research team and the 4-H regional/county 4-H network since stakeholder engagement and shared learning at this intersection is critical for sustained dissemination (Brownson et al., 2018; Estabrooks et al., 2019). The SWITCH research team comprised experts in a broad array of fields related to health promotion and implementation science, thus providing a rich, interdisciplinary team to guide the planning and evaluation. However, the participatory approach with schools and the formal integration with 4-H leaders in the project provided unique transdisciplinary perspectives. The present study provides an in-depth process and impact evaluation of the intentional capacity-building steps used to transition the project for broader dissemination through the state 4-H/Extension network. The following primary research questions guided this evaluation:

-

1.

To what degree did county 4-H Staff feel motivated and incentivized to support school wellness change through SWITCH?

-

2.

How did 4-H Staff perceive the training and preparation for their role as liaisons to schools in SWITCH?

-

3.

What are the perceptions of 4-H Staff regarding their role in ongoing school wellness programming.?

Method

The study used a mixed methods approach to evaluate the transdisciplinary strategies designed to engage and build capacity in 4-H staff to assist schools in SWITCH programming. All research procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the investigators’ home institution. A total of 30 elementary schools were enrolled in the 2019 iteration of SWITCH, but emphasis was placed on training and support provided by the 4-H state-level coordinators (n = two) in supporting schools in their local counties. A total of 40 4-H staff (25 CYC and 15 YPS) participated in the project but in most cases, perceptions were summarized at the school level (i.e., n = 30). Schools were from 24 of the 99 different counties in Iowa (24%), predominantly based in rural settings (n = 20; 66.6%), and with small enrolment numbers (average = 241 students). The students in these schools were predominantly white (87%) and just under half qualified to receive free/reduced-priced lunch as per specifications of the National School Lunch Program (NSLP).

Overview of SWITCH and the Role of 4-H Extension

The original “Switch” intervention program was established with the vision of ‘helping youth to switch what they do, view and chew’ (Eisenmann et al., 2008; Gentile et al., 2009). It was originally designed to work through schools to reach parents, but was re-branded as School Wellness Integration Targeting Child Health (SWITCH®), as a means to conceptualize a Whole-of-School approach and the emphasis on training schools to implement programming on their own. In the revised implementation framework (Chen et al., 2018), schools are guided through a capacity-building process to develop and sustain wellness programming based on the same SWITCH themes and constructs. As part of the process, schools establish a team of three leaders that work collaboratively as a School Wellness Team (SWT) to lead programming. The SWTs are encouraged to follow a set of specific ‘quality elements’ that define effective implementation. The five main quality elements are: (a) integration of SWITCH across the school environment through use of program materials; (b) engaging and gaining input from parents and community stakeholders; (c) involving students as leaders in wellness programming; (d) promoting self-monitoring through the online portal; and (e) weekly meetings as a team to plan implementation. Teams are encouraged to promote ‘best practices’ in three targeted settings (classroom, lunchroom and physical education) but they have autonomy to adapt programming to fit their local needs. The intervention is implemented over a 12-week period in the spring following comprehensive in-person and online training in the preceding fall semester.

School programming is most directly supported through the use of a customized content-management system (CMS) that allows the SWT to coordinate local SWITCH programming and allows for youth to learn self-monitoring skills (McLoughlin et al., 2019). Capacity within the SWT is built through an annual school wellness conference, a sequential set of preparatory webinars, and an online community of practice (CoP) network that allows the SWT (and other school leaders) to share strategies with their peers from other schools. Schools are provided with resources and base program materials including setting-specific resource modules and posters but they are given autonomy with regard to how they were used within their school. The standardized training process ensured that the approach can be systematically evaluated while the flexible implementation enables the programming to be tailored and customized to fit local needs and interests.

Study Design

The study was designed to evaluate engagement and motivation of county and regional 4-H leaders to continue to support the broader dissemination of SWITCH across the state. The 4-H / Extension network is ideally positioned to serve this type of public health role (4-H,n.d.; Braun et al., 2014), but transdisciplinary approaches were important to ensure that the programming was also aligned with 4-H goals and with the roles of county-based 4-H leaders. Experts in dissemination research (Estabrooks et al., 2019) have specifically recommended this type of integrated research-practice partnership to help ensure that interventions can be sustained in practice.

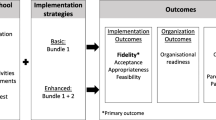

The transdisciplinary collaboration between 4-H and SWITCH evolved over a two to three-year time span as part of the USDA-funded dissemination project (USDA NIFA grant (015-68,001-23,242). A state 4-H program leader and a regional youth programming specialist have worked closely with the research team on the project and they have gradually assumed more direct roles in promoting and implementing SWITCH. These individuals also attend regular evaluation meetings with the SWITCH research team to provide input and guidance on issues relevant to program implementation and evaluation. The transdisciplinary relationships explored in the present study focus primarily on the more distributed relationships between the SWITCH research team, county-level staff, and the SWT that implemented SWITCH. The ways in which county 4-H Extension staff involvement facilitated SWT implementation and SWITCH research team’s understanding of key facilitators/barriers to implementation was of key interest, since they are able to provide more localized support. An adapted implementation model depicting the role of state and local 4-H support as part of the capacity-building process is provided in Fig. 1.

Systematic training and communications were used by the state 4-H youth coordinators to inform the regional YPS and CYC specialists about the opportunities and roles of 4-H in the implementation of SWITCH. The information was shared with all staff through both in-person and online meetings, but more specific trainings were provided for those that were in counties with registered SWITCH schools. Staff in these counties were connected with school leaders and were invited to attend the in-person conference with school leaders from their county who had already registered their school. Staff were also provided with training opportunities to develop skills needed to assist schools in planning and running wellness programming. In previous iterations of SWITCH, SWTs were supported by the project team to launch and run programming, but the goal in this transition step was to position the CYC staff to provide more localized and personalized support. The SWITCH research team led an initial call with the SWT and encouraged 4-H Staff to join; however, the staff were encouraged to lead the two subsequent ‘checkpoint’ calls to more actively support schools in their county. They were given materials (i.e., sample questions and scripts) to guide these conversations but were given freedom to visit schools in-person, conduct phone calls, or use video conferencing software based on their schedules and SWT availability.

Measures

The majority of measures used to evaluate SWITCH are built into the CMS to facilitate use by schools and the research team. However, additional qualitative and quantitative measures were developed to capture engagement, motivation, and perceptions of 4-H leaders during SWITCH implementation.

Process Measures

Process data of 4-H staff involvement were obtained through tracking logs compiled by the state 4-H leaders to provide objective information on engagement with SWITCH. The logs captured attendance and involvement in the various trainings and professional development opportunities over a nine-month period ranging from August (prior to the start of SWITCH training) through May (following SWITCH implementation by the schools). The primary training opportunities were a summer training institute on SWITCH and a supplemental course on motivational interviewing (MI) techniques designed to train staff in effective ways to engage SWT.Footnote 1 The online MI course was specifically designed for 4-H Staff since the use of MI was incorporated as part of the SWITCH implementation framework to promote autonomy and motivation within school teams (Chen et al., 2018). Key insights were also shared at the annual school wellness conference used to train school leaders how to implement SWITCH. The 4-H Staff were encouraged to attend the annual training conference with members of the school teams to facilitate connections and collaboration.

As part of their role, 4-H Staff also attended monthly webinars from September 2018 to April 2019 where different topics were addressed to facilitate their supporting role with schools. Attendance at webinars was monitored each month and state leaders recorded whether 4-H Staff completed scheduled checkpoint calls with schools at the two timepoints during implementation (~ halfway through and at the end of SWITCH implementation). This provided data on the degree to which they were involved with schools in their county and the level of support they provided. Based on the observed involvement, state 4-H leaders provided categorical rankings of engagement for each school (one = Low / two = Moderate/three = High). The purpose of this indicator was to enable outcomes to be evaluated with both objective and subjective reports of 4-H engagement.

Checkpoint Surveys

Throughout the structured 12-week implementation phase, the 4-H staff were asked to complete surveys at the middle (six weeks) and end (post-week 12) of formal programming to capture their involvement and engagement with the schools. These surveys were captured prior to the planned checkpoint calls/visits with the schools and included questions that captured perceptions of competence to perform job roles well as well as the aspects which motivate them to become involved in SWITCH. At the end of implementation, an additional set of items captured the relative degree of autonomous versus controlled motivation for engaging in SWITCH based on the Self-Regulation of Educators Questionnaire (SREQ; Vazou, Welk, Chen, & Bai, 2016). This adapted version of the instrument was refined to gauge feelings of 4-H Staff regarding motivation toward their roles in supporting schools. Established frameworks to guide dissemination and implementation of evidence-based interventions document the need to understand and assess motivation of individuals and organizations involved in the intervention activities (Damschroder et al., 2009; Kirk et al., 2016; Lonsdale et al., 2016; Wandersman et al., 2008). Autonomous motivation refers to an individual’s intrinsic desires to carry out a certain behaviour, whereas controlled motivation represents a combination of external and less innate desire to perform a certain behaviour (Li, Wang, You, & Gao, 2015; Weinstein & Ryan, 2010). Both forms of motivation are drivers of behaviour change, but research has shown that autonomous motivation is associated with more altruistic and innovative practices in teaching professions (Pavey, Greitemeyer, & Sparks, 2012; Weinstein & Ryan, 2010). Understanding the degree to which county Extension staff are driven to help implement SWITCH is important to enhance broader dissemination. A full list of questions and the classification of autonomous and controlled motivation can be found in Table 1.

Qualitative Interviews

Qualitative data were collected using structured interviews with 4-H Staff at the end of the programming. All 4-H Staff were invited to participate in an interview, and 22 participants (73%) completed this part of the evaluation, representing 20 of the 99 (20%) counties across Iowa. Questions focused on the degree to which staff were prepared/motivated for their role in supporting schools, to what degree SWITCH helped them connect with schools through programming, and the factors that impacted successful implementation in school settings. Examples include, “What were your original perceptions of SWITCH prior to beginning the program? Have these changed at all?” and “What were some of the strengths and weaknesses of programming?” They were also asked questions related to their desired future involvement in SWITCH, and ended with Likert scale questions that asked them: (1) how well did they feel prepared for their role in SWITCH, (2) how much their involvement in SWITCH helped them to carry out their role within Extension, and (3) their likelihood of continuing to work with SWITCH next year (one = poorest rating; five = highest rating). This provided valuable information that may influence the school-Extension partnership and subsequent dissemination efforts. All interviews were conducted over the phone and transcribed verbatim. Informed consent was obtained prior to completion of checkpoint surveys and interviews through a consent script shown (on survey) and read aloud (interview) prior to completion of each item. Participants were informed that they could stop the procedures at any time without negative consequence to their role as 4-H staff. All interviews were conducted by an independent survey and interview group in attempt to ensure anonymity and reduce social desirability in providing honest responses to the questions posed.

Data Analysis

The focus of the analyses was on the process evaluation of Extension involvement and perspectives of 4-H Extension staff regarding their involvement in supporting SWITCH implementation. The mixed methods design facilitated a richer understanding of the transdisciplinary approaches used to support sustainability of the research - practice partnership over time.

Quantitative Analyses

Process data captured throughout the project were compiled and coded to capture the overall degree of engagement by the participating regional and county 4-H staff. A weighted index was computed to capture this engagement since some events were longer and more important than others in the capacity-building process. The weighted index provided five points for involvement in the summer training, involvement in the MI course, and attendance at the annual SWITCH conference (15 points total) and one point each for attendance on the monthly/school webinars (eight points total) so the total possible score was 23. Descriptive statistics were computed to report the engagement in specific components of the training as well as the involvement of staff in the checkpoint calls with schools. Pearson bivariate correlations were also computed between the subjective ratings from state 4-H coordinators and the overall composite score to evaluate the relative agreement between these two indicators of engagement.

Data from the checkpoint surveys were downloaded from the online survey tool and coded to capture the motivations and perceptions of 4-H staff. Items from the SREQ instrument were processed using standard methods for these scales to compute separate indicators of ‘autonomous’ and ‘controlled’ motivation. The relative scores on these scales capture the degree to which 4-H Staff were intrinsically or extrinsically motivated to engage with schools as part of their role in 4-H/Extension. The other items on satisfaction and perceived engagement were summarized similarly to compute key indicators for the evaluation. Responses from the second checkpoint survey were used if available, but values from the first checkpoint survey were used in cases where the second survey was missing (n = two). After generating means from survey data, Pearson bivariate correlations were calculated between motivation items (autonomous and controlled), satisfaction with training/support and overall program, and perceived competence toward conducting checkpoint calls with schools.

Qualitative Analyses

All transcripts were uploaded into NVivo (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia) prior to analysis. Given the lack of extant literature on the transdisciplinary processes by which school programming is supported by local Extension, data analysis followed a grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 2015). This approach allows researchers to systematically extract meaning and common themes from extensive qualitative data and to remain as inductive as possible so as to prevent their own internal biases from being reflected in the analyses (Strauss & Corbin, 2015).

The process took place in a series of three distinct phases: open coding, axial coding, and inductive analysis. The purpose of open coding was to gather high-level perceptions of data and generate initial themes which are later tested in axial coding. This process entailed reviewing a subsample of transcripts (10) and developing an initial codebook in NVivo. Broad concepts were captured in this initial coding, before slowly developing main/first order themes (e.g., building relationships) and second order/subthemes (e.g., collaborating with teachers) that align with these themes. The purpose of axial coding was to test the un-coded data against the initial codebook for agreement and to make refinements to themes. Where new ideas/themes emerged, the coders developed new nodes in NVivo to accommodate emerging concepts. Similarly, where new data did not converge with existing theme names but were related, the coders discussed changing certain theme titles to better reflect the data coded within these themes. The finalizing of themes followed an inductive approach to organize themes in a meaningful way that addressed the research questions, as a means to further guide knowledge about transdisciplinary research (Strauss & Corbin, 2015).

To establish trustworthiness and credibility in data analysis, additional steps were followed based on previously established criteria (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). First, upon developing codes from the data, the lead researcher regularly conducted peer debriefing with other members of the research team to minimize personal bias in reporting main themes. Second, methods, sources, and participant triangulation were employed throughout analysis to develop themes that encompassed multiple individual’s perspectives while taking objective data into consideration (Patton, 2015; Whittemore, Chase, & Mandle, 2001). Finally, an audit trail was developed and maintained throughout all phases of analysis to document trends in interview data and the dialogue that took place between the main and second coder (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Whittemore et al., 2001). Here, the researchers took rich notes regarding the coding process and the ways in which coding evolved over time.

Results

The study examines the value of the transdisciplinary approaches used to build interest and engagement within the 4-H network to support the implementation of SWITCH in schools. The 4-H leaders had high levels of engagement and generally high motivation to support schools. Details on the process and impact evaluation are summarized below.

Process Evaluation

The involvement of 4-H staff in the various SWITCH training activities is summarized in Fig. 2. Overall engagement was high as 77% attended summer training, 47% completed the supplemental MI training / coursework, 80% attended the SWITCH training conference with schools, 77% attended two or more staff webinars, and 67% organized/attended at least two checkpoint calls with schools. The average score on the composite indicator of engagement (reflecting training, webinars, checkpoint calls) was 14.07(± 4.1) out of the possible 23 points. The average engagement score-assigned by state 4-H coordinators-averaged 2.29(± 0.9) on the three-point scale with seven (23.3%) scoring a one, four (13.3%) scoring a two and 19 (63.3%) scoring a three. This demonstrates a moderate-to-high engagement as deemed by state-level staff.

Correlation analyses revealed a significant positive relationship between the state-level assigned engagement rating and the composite score (r = 0.752, p < 0.0001), the number of webinars attended (r = 0.634, p < 0.0001) and the number of checkpoint calls attended/led (r = 0.769, p < 0.0001). Further, the composite score was positively associated with the number of checkpoint calls attended/led (r = 0.762, p < 0.0001). These data demonstrate the utility of the composite score and the 4-H rating as indicators of Extension involvement during SWITCH.

Impact Evaluation

A primary variable of interest in the impact evaluation was the perceived motivation of the 4-H Staff for engaging with schools. To examine this, plots of autonomous/controlled motivation were developed for each individual. The results show that individuals can have aspects of both types of motivation, but there is a general tendency for higher autonomous motivation to correspond with lower levels of controlled motivation (see Fig. 3). Descriptive data are shown in Table 2.

Correlations were computed to examine relationships between motivational orientation and perceptions of SWITCH training and involvement (See Table 3). Autonomous motivation was not positively associated with any of the other variables (p > 0.05), and was moderately negatively associated with the degree to which participants felt motivated (p = 0.011) and valued (p = 0.023) in conducting the checkpoint calls. Non-significant relationships were also observed between controlled motivation and feelings of optimism (p = 0.742) or satisfaction (p = 0.188).

With regard to perceptions of leading checkpoint calls, 4-H Staff reported moderate ratings related to preparation, and generally favourable perceptions related to motivations and energy regarding the task of supporting schools. Positive associations were noted between feeling prepared and motivated (p = 0.002) and energized (p = 0.003) for leading checkpoint calls. The degree to which staff felt energized was positively associated with preparation (p = 0.003) but no other variables. Feeling valued was associated with the most variables including feeling prepared (p = 0.004), energized (p = < 0.0001), and optimistic (p = 0.000) for conducting checkpoint calls. Program satisfaction was negatively associated with various perceptions related to leading checkpoint calls as well as with feeling valued.

Qualitative Data Themes

The evaluation of qualitative interview data revealed three overarching themes. Participants spoke of their relationship building efforts with schools, the ways in which supporting schools in SWITCH related to their job roles and responsibilities, and the perceived facilitators and barriers for broader implementation and dissemination through the state 4-H network. Where relevant, subthemes were introduced that fit within broader concepts. All meaning units (i.e., coding inferences for each specific theme) for themes/subthemes are listed with salient quotations in Table 4.

-

1.

Building Relationships with Schools (43 meaning units)

The ways in which 4-H Staff collaborated with SWITCH schools manifested in a variety of ways; some staff chose to insert themselves in to the SWT and play an equal role, whereas some took a more distal role and provided advice and support when needed. Many 4-H Staff reported that SWITCH facilitated relationship building between them and the schools in their county by providing a vehicle for communication and collaboration. In this regard, Extension staff were effectively positioned as intermediaries between the SWT and the SWITCH coordinating team at the state level. They were able to answer specific questions, offer feedback and provide more localized support than would be possible through the state network.

The efforts to disseminate SWITCH have been ongoing for the past two to three years, and some schools already had a year (or two) of experience with the program prior to the 2018–2019 implementation cycle. In some cases, the schools served as a reference point to 4-H Staff who weren’t familiar with programming. Even if schools didn’t need much support they still seemed to value the opportunity to connect with and have support from the 4-H Staff.

-

2.

Utility of Training for Support Role (31 meaning units)

The 4-H Staff were trained to support school wellness efforts through summer professional development, training in MI techniques, webinars, and the school wellness conference. For some staff, this was their first experience with school wellness programming despite leading similar efforts in their respective counties, thus training served as vital preparation for their supporting role in SWITCH. Many staff alluded to the MI training as a key preparation tool since it helped them to practice before leading checkpoint calls with schools. When asked to rate the degree to which training prepared them to lead calls, 4-H Staff rated this as 4.1 out of five (see Fig. 4). In addition to initial training, staff mentioned the importance of ongoing support from the state 4-H Staff throughout the training and implementation phase. When programming was underway, staff talked about how they were able to apply the skills developed through MI training directly to facilitating systems change in schools.

Fig. 4 Subjective ratings of SWITCH programming and relevance to job roles through interview data (n = 22). Preparation = Satisfaction of preparation for support role; Role Relevance = perceived relevance to job roles; Continue support = How supportive 4-H Staff would feel regarding continuation of role with schools

Conversely, either due to lack of training or lack of confidence after training, some staff expressed that they felt uncomfortable in leading conversations based on MI principles. Specifically, some 4-H Staff attributed a lack of time to not completing training and thus felt unprepared to lead calls. Some staff expressed that, despite receiving training and support, they felt it wasn’t extensive enough and they weren’t given enough specific information regarding how to contact schools and what ideas to provide. This implies that, although providing 4-H Staff with flexibility regarding how they chose to support schools promotes autonomy, an opportunity may have been missed to provide them with concrete examples of messages to send, ideas to provide, or ways to embed themselves in programming.

-

3.

Factors Impacting Involvement in School Wellness Programming (105 meaning units)

Finally, a third major theme within the data related to the logistical and programmatic factors that impacted implementation. Three subthemes emerged from this theme in relation to how Extension perceived supporting schools as a relation to their overall job roles, considerations for further supporting roles, and barriers to implementation. When asked to rate the degree to which facilitating school wellness programming aligned with their job roles, 4-H Staff reported this as 3.8 out of five, which was the lowest of all three ratings (see Fig. 4). Many 4-H staff were already involved in programming related to health and wellness in some capacity and were able to find ways to support the efforts of schools to enhance school wellness programming through SWITCH.

In addition to alignment with job roles and responsibilities, many staff discussed how they envision supporting SWITCH more broadly in their respective counties in the future. When asked to rate the degree to which they want to continue supporting SWITCH schools in future, 4-H Staff reported this was 4.7 out of five, the highest of all three ratings (see Fig. 4). Despite the clear synergies between Extension job roles and the overall structure of SWITCH programming, the interviews highlighted communication/collaboration challenges which may hinder involvement by 4-H leaders. Some reported a lack of contact from schools and a lack of buy-in from SWT. This suggests that some schools were not as invested as 4-H Staff, creating tensions between these two systems and potentially hindering collaboration. Other barriers, such as weather, time, and financial constraints were mentioned by staff members as potential barriers to engagement. Weather issues often interfered with implementation, increasing the pressure on instructional time for core subjects, which meant that there was a lesser focus on SWITCH themes and coordination of wellness programming.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the transdisciplinary approaches used to transition the SWITCH project for broader dissemination through the state 4-H/Extension network. Findings from reviews of school wellness programming have emphasized the importance of understanding environmental and systemic factors influencing the scale-up and dissemination of evidence-based approaches (McKay et al., 2019). Consistent with these recommendations, the SWITCH project has used a series of studies to sequentially test different facets of our implementation process. The emphasis in SWITCH has been on building capacity for schools to take responsibility for internal wellness programming; however, consistent with the vision of the Cooperative Extension system (Braun et al., 2014), 4-H staff were trained to provide local support and assistance. The advantage of this model from a dissemination perspective is that it allows for standardized and centralized training but potential for localized support. This study provided valuable information to ensure that dissemination efforts consider the needs and interests of the county-level stakeholders.

Exposure of 4-H Staff to SWITCH evolved over a two to three-year time span, but the focus of this paper was on evaluating the motivation and engagement over the most recent round of programming. The systematic tracking of process data provided an objective indicator of exposure while the survey data obtained directly from the 4-H staff provided direct measures of motivation and engagement. The process data demonstrate that 4-H Staff were highly engaged with SWITCH programming and took advantage of professional development opportunities; such engagement was strongly related to the ordinal levels of engagement assigned by state 4-H staff. These findings support the value of transdisciplinary approaches for both building capacity and enhancing engagement with SWITCH programming.

Survey data revealed that 4-H staff reported high autonomous motivation and moderate controlled motivation toward supporting schools in SWITCH. It is not surprising that motivation was both autonomous and controlled, as the staff were asked to take on SWITCH as an additional responsibility instead of as an optional program to help promote school wellness. A lack of association between constructs of motivation and perceptions toward conducting checkpoint calls may also be interpreted in this way, as staff may be highly autonomously motivated to support schools in SWITCH programming but may still lack confidence to lead checkpoint calls. Such findings are contextualized by prior research demonstrating that 4-H staff may not hold strong experiences in evidence-based prevention programs, which impacted their perceptions toward dissemination through schools (Perkins, Chilenski, Olson, Mincemoyer, & Spoth, 2014). These findings demonstrate the importance of providing ongoing training and support to 4-H Staff during broader dissemination, so that they feel competent and able to help propagate wellness initiatives in schools.

The findings from survey data are supported by themes from interviews, in that many 4-H staff members cited initial trainings in MI principles and engaging in the school wellness conference as vital to their preparation for support roles. Many 4-H staff lacked experience with wellness initiatives prior to SWITCH, thus were often merely one step ahead of the schools, and in some cases were learning at the same pace. These findings are reflected by prior work to investigate the readiness of state 4-H Staff regarding dissemination of an evidence-based delivery program (Spoth et al., 2015). In particular, the authors noted that the readiness of state 4-H Staff to disseminate programming was lower than that of department of education representatives (Spoth et al., 2015). Lack of financial investment and training were cited as potential reasons the discrepancy (Spoth et al., 2015). The fact that some staff members in the present study felt that such training was not sufficient (or that they did not have time to complete training) indicates the need for innovation in professional development, especially for staff who travel to communities and schools for programming and cannot commit to in-person and fixed time training. As such, ongoing support must be provided to those in facilitator roles so that they are equipped with the knowledge and capacity to aid in program dissemination.

Other pertinent findings demonstrated the potential for SWITCH to act as a vehicle for school-Extension collaboration; new relationships were formed and existing ones were fortified through facilitating wellness programming efforts. Fostering relationships between 4-H Extension and intervention delivery sites (i.e., schools) is an integral step in ensuring the sustainability of SWITCH across the state. Local support has been shown to be important in other school studies (Linnell, Zidenberg-Cherr, Scherr, & Smith, 2018; Reed et al., 2016). For example, Reed and colleagues (2016) evaluated a teen tobacco prevention program and found that localized support (i.e., county-based) was a successful strategy to enable program adoption and implementation. In this case, Extension officers were able to form partnerships with local schools and the local prevention research center to increase the reach of programming. Similarly, Linnell et al. (2018) studied the degree to which an Extension classroom nutrition program could be implemented by classroom teachers as a means to further disseminate programming, but found that this task was more difficult than initially perceived in that teachers needed more support from local 4-H Staff. The authors concluded that further training and a closer relationship between Extension and classroom teachers was needed in order to effectively deliver program curricula (Linnell et al., 2018). These findings are consistent with the findings in the present study showing the importance of mutually beneficial relationships between community partners (i.e., 4-H Extension) and schools.

It is encouraging that nearly all 4-H staff reported that SWITCH was directly tied to their ongoing work with schools or that it was highly relevant to job roles and responsibilities. Some 4-H staff took initiative to lead programming efforts or events in schools, illustrating their commitment to school wellness and building capacity in schools. Previous research has demonstrated the value of 4-H Staff involvement and programmatic support for school-based activity programming (Wade & Nichols, 2008) and the advantages of broader involvement in public health programming has been well documented (Dwyer et al., 2017). Such findings provide impetus for 4-H Staff to play a role in program facilitation through teaching lessons, leading school activities, and other school wellness initiatives through SWITCH.

Despite program successes, participants did report barriers to programming and working with schools in this particular capacity. In some cases, these barriers related to program components that could be modified, such as the training and preparation of schools prior to SWITCH implementation and financial aspects of programming. The 4-H staff also commented on the difficulty of conducting checkpoint calls, citing the narrow time frame (~ two weeks) and scheduling issues as key reasons. Scholars have stressed the importance of providing 4-H Staff with autonomy over evaluation procedures as a means to strengthen program delivery (Balis, John, & Harden, 2019). Consistent with other research-practice partnerships (Estabrooks et al., 2019), the feedback will be used to streamline the roles and collaborative process between county 4-H leaders and schools. The feedback and suggestions on how to better coordinate the delivery of SWITCH is vital to ensuring sustainability of programming as the program continues to expand to more counties in the state.

Given a lack of prior research that illustrates how 4-H Staff can facilitate dissemination of school wellness programming, this study adds great value. Nonetheless, there are a few limitations that should be noted. First, the relatively small sample size and missing data from some measures limits our ability to draw concrete conclusions regarding the feasibility of Extension involvement in the scale-up and dissemination of SWITCH. Secondly, the naturalized design did not allow for randomization into comparison groups so common sources of bias (e.g., social desirability) can potentially influence the results (Grimm, 2010). Finally, due to our efforts to gain trust of 4-H staff, and keep checkpoint surveys anonymous, we were not able to link self-reported motivation/preparation data to other sources of data. Thus, we could not draw direct connections between their engagement and perceptions of autonomous/controlled motivation. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights about the value of the transdisciplinary approach used to engage 4-H staff to facilitate SWITCH programming.

Implications for Future Dissemination

Findings from the present study highlight the synergies and advantages of 4-H Extension involvement in the broader dissemination of SWITCH in Iowa. The transdisciplinary partnership with 4-H was nurtured by good communication, systematic training, and collaboration strategies that provided mutual benefits. The mixed methods approach used in the study provided insights into this process that could not be gleaned through surveys or objective means alone. The interview data demonstrated the value of SWITCH as a vehicle for 4-H to reach and serve schools within their respective counties. It also documented that 4-H staff improved skills that can be applied across all youth programming mechanisms. Addressing the reported barriers expressed by the 4-H staff will prove helpful in ensuring broader reach of SWITCH and improved sustainability over time.

Notes

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a rigorously defined conversation skill that has been widely used in behavior change applications to promote autonomous motivation. In SWITCH, MI-based approaches and strategies are used to empower and encourage school leaders to take responsibility for local programming in their own schools.

References

4-H. (n.d.). 4-H Mission Mandates. Retrieved from https://nifa.usda.gov/sites/default/files/resource/4-HMissionMandates.pdf.

Balis, L. E., John, D. H., & Harden, S. M. (2019). Beyond evaluation: using the RE-AIM framework for program planning in extension. Journal of Extension, 57(2), 2TOT1.

Berger-Jenkins, E., Rausch, J., Okah, E., Tsao, D., Nieto, A., Lyda, E., et al. (2014). Evaluation of a coordinated school-based obesity prevention program in a Hispanic community: Choosing healthy and active lifestyles for kids/healthy schools healthy families. American Journal of Health Education, 45, 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2014.932724.

Biddle, S. J. H., & Asare, M. (2011). Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(11), 886–895. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2011-090185.

Braun, B., Bruns, K., Cronk, L., Kirk Fox, L., Koukel, S., Le Menestrel, S., Warren, T. (2014). Cooperative Extension’s National Framework for Innovation Report 1420 Academic Medicine. Retrieved January 2, 2020, from https://www.aplu.org/members/commissions/food-environment-and-renewable-resources/CFERR_Library/national-framework-for-health-and-wellness/file.

Brownson, R. C., Eyler, A. A., Harris, J. K., Moore, J. B., & Tabak, R. G. (2018). Getting the word out. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 24(2), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000673.

Cassar, S., Salmon, J., Timperio, A., Naylor, P.-J., van Nassau, F., Contardo Ayala, A. M., et al. (2019). Adoption, implementation and sustainability of school-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour interventions in real-world settings: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 16(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0876-4.

Centers for Disease Control. (2014). Whole school, whole community, whole child: A collaborative approach to learning and health, 2014. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/wscc/wsccmodel_update_508tagged.pdf..

Chen, S., Dzewaltowski, D. A., Rosenkranz, R. R., Lanningham-Foster, L., Vazou, S., Gentile, D. A., et al. (2018). Feasibility study of the SWITCH implementation process for enhancing school wellness. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6024-2.

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

Donnelly, J. E., Hillman, C. H., Castelli, D., Etnier, J. L., Lee, S., Tomporowski, P., et al. (2016). Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: A systematic review. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 48, 1197–1222. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000901.

Dwyer, J. W., Contreras, D., Eschbach, C. L., Tiret, H., Newkirk, C., Carter, E., et al. (2017). Cooperative extension as a framework for health extension. Academic Medicine, 92(10), 1416–1420. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001640.

Dzewaltowski, D. A., Rosenkranz, R. R., Geller, K. S., Coleman, K. J., Welk, G. J., Hastmann, T. J., et al. (2010). HOP’N after-school project: An obesity prevention randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity, 7, 90–101.

Dzewaltowski, D. A., Estabrooks, P. A., & Johnston, J. A. (2002). Healthy youth places promoting nutrition and physical activity. Health Education Research, 17(5), 541–551. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/17.5.541.

Eisenmann, J. C., Gentile, D. A., Welk, G. J., Callahan, R., Strickland, S., Walsh, M., et al. (2008). SWITCH: Rationale, design, and implementation of a community, school, and family-based intervention to modify behaviors related to childhood obesity. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 223. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-223.

Estabrooks, P. A., Harden, S. M., Almeida, F. A., Hill, J. L., Johnson, S. B., Porter, G. C., et al. (2019). Using integrated research-practice partnerships to move evidence-based principles into practice. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 47(3), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000194.

Friend, S., Flattum, C. F., Simpson, D., Nederhoff, D. M., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2014). The researchers have left the building: What contributes to sustaining school-based interventions following the conclusion of formal research support? Journal of School Health, 84(5), 326–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12149.

Gentile, D. A., Welk, G. J., Eisenmann, J. C., Reimer, R. A., Walsh, D. A., Rusell, D. W., et al. (2009). Evaluation of a multiple ecological level child obesity prevention program: Switch® what you Do, View, and Chew. BMC Medicine, 7, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-7-49.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Grimm, P. (2010). Social desirability bias. In N. K. Malhotra (Ed.), Wiley international encyclopedia of marketing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444316568.wiem02057.

Institute of Medicine. (2013). Educating the student body: Taking physical activity and physical education to school. Retrieved February 16, 2017, from https://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2013/Educating-the-Student-Body-Taking-Physical-Activity-and-Physical-Education-to-School.aspx.

Iowa 4-H Extension. (n.d.). 4-H Youth Development: Healthy Living. Retrieved March 12, 2020, from https://www.extension.iastate.edu/4h/program-list.

Kirk, M. A., Kelley, C., Yankey, N., Birken, S. A., Abadie, B., & Damschroder, L. (2016). A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implementation Science, 11(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z.

Kreuter, M. W., & Wang, M. L. (2015). From evidence to impact: recommendations for a dissemination support system (Report). New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2015(149), 11. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20110.

Lee, J. A., Welk, G. J., Vazou, S., Ellingson, L. D., Lanningham-Foster, L., & Dixon, P. (2018). Development and application of tools to assess elementary school wellness environments and readiness for wellness change (doctoral dissertation). Iowa State University.

Li, M., Wang, Z., You, X., & Gao, J. (2015). Value congruence and teachers’ work engagement: The mediating role of autonomous and controlled motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 80, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.021.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry (Vol. 75). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Linnell, J. D., Zidenberg-Cherr, S., Scherr, R. E., & Smith, M. H. (2018). Building the capacity of classroom teachers as extenders of nutrition education through extension: Evaluating a professional development model. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 6(1), 58–75.

Lonsdale, C., Sanders, T., Cohen, K. E., Parker, P., Noetel, M., Hartwig, T., et al. (2016). Scaling-up an efficacious school-based physical activity intervention: Study protocol for the ‘internet-based professional learning to help teachers support activity in youth’ (iPLAY) cluster randomized controlled trial and scale-up implementation evaluat. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 873. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3243-2.

McKay, H., Naylor, P.-J., Lau, E., Gray, S. M., Wolfenden, L., Milat, A., et al. (2019). Implementation and scale-up of physical activity and behavioural nutrition interventions: an evaluation roadmap. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 16(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0868-4.

McLoughlin, G. M., Rosenkranz, R. R., Lee, J. A., Wolff, M. M., Chen, S., Dzewaltowski, D. A., et al. (2019). The importance of self-monitoring for behavior change in youth: Findings from the SWITCH® school wellness feasibility study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 3806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203806.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Pavey, L., Greitemeyer, T., & Sparks, P. (2012). “I help because i want to, not because you tell me to”: Empathy increases autonomously motivated helping. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(5), 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211435940.

Perkins, D. F., Chilenski, S. M., Olson, J. R., Mincemoyer, C. C., & Spoth, R. (2014). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Commitment Concerning Evidence-Based Prevention Programs: Differences between Family and Consumer Sciences and 4-H Youth Development Educators. Journal of Extension, 52(3), 3FEA6. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25722498.

Reed, D., Jarrett, T., Farley, J., Richards, T., Mcdonald, D., & Dino, G. (2016). Lessons of partnership: Successes and challenges associated with the dissemination of the not-on-tobacco program within cooperative extension service framework. Journal of Youth Development, 11(1), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.5195/JYD.2016.435.

Singh, A., Uijtdewilligen, L., Twisk, J. W. R., van Mechelen, W., & Chinapaw, M. J. M. (2012). Physical activity and performance at school: A systematic review of the literature including a methodological quality assessment. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.716.

Spoth, R., Schainker, L., Redmond, C., Ralston, E., Yeh, H.-C., & Perkins, D. (2015). Mixed picture of readiness for adoption of evidence-based prevention programs in communities: Exploratory surveys of state program delivery systems. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(3–4), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9707-1.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

United States Department of Agriculture. (2016). Final Rule: Local School Wellness Policy Implementation Under the HHFKA of 2010. Retrieved from https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2016/07/29/2016-17230/local-school-wellness-policy-implementation-under-the-healthy-hunger-free-kids-act-of-2010.

Vazou, S., Welk, G., Chen, S., & Bai, Y. (2016). Self-regulations for educators questionnaire (SREQ): Measurement development and validation. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 87(S2), A6.

Wade, K., & Nichols, A. (2008). Catch ‘em being good:” An extension service and state school system team up to promote positive outcomes for youth. Journal of Youth Development, 3(3), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.5195/JYD.2008.293.

Wandersman, A., Duffy, J., Flaspohler, P., Noonan, R., Lubell, K., Stillman, L., et al. (2008). Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: The interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3), 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z.

Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016984.

Welk, G. J., Chen, S., Nam, Y. H., & Weber, T. E. (2015). A formative evaluation of the SWITCH® obesity prevention program: print versus online programming. BMC Obesity, 2, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40608-015-0049-1.

Whittemore, R., Chase, S. K., & Mandle, C. L. (2001). Validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 11(4), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973201129119299.

Funding

This research was funded by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) NIFA program (GRANT11683080).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (blinded IRB; Application Number: 14-651-00) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McLoughlin, G.M., Vazou, S., Liechty, L. et al. Transdisciplinary Approaches for the Dissemination of the SWITCH School Wellness Initiative Through a Distributed 4-H/Extension Network. Child Youth Care Forum 50, 99–120 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09556-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09556-3