Abstract

Purpose

SEER data are widely used to study rural–urban disparities in cancer. However, no studies have directly assessed how well the rural areas covered by SEER represent the broader rural United States.

Methods

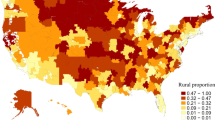

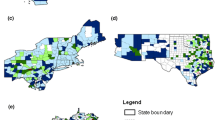

Public data sources were used to calculate county level measures of sociodemographics, health behaviors, health access and all cause cancer incidence. Driving time from each census tract to nearest Commission on Cancer certified facility was calculated and analyzed in rural SEER and non-SEER areas.

Results

Rural SEER and non-SEER counties were similar with respect to the distribution of age, race, sex, poverty, health behaviors, provider density, and cancer screening. Overall cancer incidence was similar in rural SEER vs non-SEER counties. However, incidence for White, Hispanic, and Asian patients was higher in rural SEER vs non-SEER counties. Unadjusted median travel time was 53 min (IQR 34–82) in rural SEER tracts and 54 min (IQR 35–82) in rural non-SEER census tracts. Linear modeling showed shorter travel times across all levels of rurality in SEER vs non-SEER census tracts when controlling for region (Large Rural: 13.4 min shorter in SEER areas 95% CI 9.1;17.6; Small Rural: 16.3 min shorter 95% CI 9.1;23.6; Isolated Rural: 15.7 min shorter 95% CI 9.9;21.6).

Conclusions

The rural population covered by SEER data is comparable to the rural population in non-SEER areas. However, patients in rural SEER regions have shorter travel times to care than rural patients in non-SEER regions. This needs to be considered when using SEER-Medicare to study access to cancer care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Code availability

STATA v16.0 was used for statistical analyses. ArcGIS was used for travel time calculations. Analysis code is available on reasonable request.

References

(2019) Overview of the SEER Program. In: National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. https://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html. Accessed 2 July 2020

Nattinger AB, McAuliffe TL, Schapira MM (1997) Generalizability of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results registry population: factors relevant to epidemiologic and health care research. J Clin Epidemiol 50:939–945

Harper S, Lynch J (2010) Selected comparisons of measures of health disparities health disparities. A review using databases relevant to Healthy People 2010 Cancer-related objectives. NCI Cancer Surveill Monogr Ser 92:1–80

Zeng C, Wen W, Morgans AK et al (2015) Disparities by race, age, and sex in the improvement of survival for major cancers: results from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program in the United States, 1990 to 2010. JAMA Oncol 1:88–96. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.161

Baldwin L-M, Cai Y, Larson E et al (2008) Access to cancer services for rural colorectal cancer patients. J Rural Health 24:390–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00186.x

Stitzenberg KB, Chang YK, Smith AB, Nielsen ME (2015) Exploring the burden of inpatient readmissions after major cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol 33:455–464. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5938

Kuo T, Mobley LR (2016) How generalizable are the SEER registries to the cancer populations of the USA? Cancer Causes Control 27:1117–1126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-016-0790-x

Probst JC, Moore CG, Glover SH, Samuels ME (2004) Person and place: the compounding effects of race/ethnicity and rurality on health. Am J Public Health 94:1695–1703. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1695

Matthews K, Croft J, Liu Y et al (2017) Health-related behaviors by urban-rural county classification—United States, 2013. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ 66:1–12

(2019) Registry Groupings in SEER Data and Statistics. In: National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. https://seer.cancer.gov/registries/terms.html. Accessed 2 Jan 2020

(2017) OMB Bulletin 17-01: revised delineations of metropolitan statistical areas, micropolitan statistical areas, and combined statistical areas, and guidance on uses of the delineations of these areas. Washington DC

Hall SA, Kaufman JS, Ricketts TC (2006) Defining urban and rural areas in U.S. epidemiologic studies. J Urban Health 83:162–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-005-9016-3

(2019) Rural-urban commuting area codes. In: United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/. Accessed 12 Apr 2019

(2019) RUCA data: using RUCA data. In: Rural Health Research Center. https://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-uses.php. Accessed 1 Sep 2019

(2019) 2019 Measures. In: County Health Rankings. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/measures-data-sources/2019-measures. Accessed 1 Aug 2019

Liu B, Parsons V, Feuer EJ et al (2019) Small area estimation of cancer risk factors and screening behaviors in US counties by combining two large national health surveys. Prev Chronic Dis 16:1–10. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.190013

(2019) Incidence rates table. In: State Cancer Profiles. www.statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/incidencerates/. Accessed 19 Jan 2020

(2019) Suppression of rates and counts. In: United States Cancer Stat. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/technical_notes/stat_methods/suppression.htm. Accessed 1 Sep 2019

Flury BK, Riedwyl H, Flury BK, Riedwyl H (2016) Standard distance in univariate and multivariate analysis. Am Stat 40:249–251

Austin PC (2011) An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 46:399–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.568786

Onega T, Duell EJ, Shi X et al (2008) Geographic access to cancer care in the U.S. Cancer 112:909–918. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23229

Diaz A, Schoenbrunner A, Pawlik TM (2019) Trends in the geospatial distribution of adult inpatient surgical cancer care across the United States. J Gastrointest Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000003366

Stitzenberg KB, Sigurdson ER, Egleston BL et al (2009) Centralization of cancer surgery: implications for patient access to optimal care. J Clin Oncol 27:4671–4678. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1715

Al-Sahaf M, Lim E (2015) The association between surgical volume, survival and quality of care. J Thorac Dis 7:S152–S155. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.04.08

Birkmeyer JD, Sun Y, Wong SL, Stukel TA (2007) Hospital volume and late survival after cancer surgery. Ann Surg 245:777–783. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000252402.33814.dd

Learn PA, Bach PB (2010) A decade of mortality reductions in major oncologic surgery: the impact of centralization and quality improvement. Med Care 48:1041–1049. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f37d5f

Ambroggi M, Biasini C, Del Giovane C et al (2015) Distance as a barrier to cancer diagnosis and treatment: review of the literature. Oncologist 20:1378–1385. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0110

Herb JN, Dunham LN, Mody G et al (2020) Lung cancer surgical regionalization disproportionately worsens travel distance for rural patients. J Rural Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12440

Wolfe MK, McDonald NC, Holmes GM (2020) Transportation barriers to health care in the United States: findings from the national health interview survey, 1997–2017. Am J Public Health 110:e1–e8. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2020.305579

Chan L, Hart LG, Goodman DC (2006) Geographic access to health care for rural Medicare beneficiaries. J Rural Health 22:140–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00022.x

Meilleur A, Subramanian S, Plascak JJ et al (2013) Rural residence and cancer outcomes in the US: issues and challenges. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 22:1657–1667. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0404.Rural

Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D et al (2002) Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care 40:IV3–IV18

Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A et al (2017) Making the case for investment in rural cancer control: an analysis of rural cancer incidence, mortality, and funding trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 26:992–997

Wingo PA, Jamison PM, Hiatt RA et al (2003) Building the infrastructure for nationwide cancer surveillance and control—A comparison between The National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (United States). Cancer Causes Control 14:175–193. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023002322935

(2020) About US Cancer Statistics. In: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/about/index.htm. Accessed 21 July 2020

(2019) National Cancer Database. In: American College of Surgeon Cancer Programs. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb. Accessed 1 Mar 2020

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge May Kuo, PhD for her assistance with the study design. Dr. Herb is partially supported by a National Service Research Award Pre-Doctoral/Post-Doctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality sponsored by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Grant No. 5T32 HS000032

Funding

Dr. Herb is partially supported by a National Service Research Award Pre-Doctoral/Post-Doctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality sponsored by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Grant No. 5T32 HS000032.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by JH, RW and PMcD. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JH and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Herb has disclosed his funding source above.

Ethical approval

This is an observational study and the data used in this study are deidentified and publicly available. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt as this is a secondary data analysis of deidentified data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Herb, J., Wolff, R., McDaniel, P. et al. Rural representation of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Cancer Causes Control 32, 211–220 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-020-01375-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-020-01375-0