Abstract

This paper explores the effects of incidental guilt on Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) decisions of retail investors. Do investors who feel guilty invest more in SRIs to clear their conscience? Are guilty investors willing to sacrifice returns to restore their moral selves? Using survey data from an online quasi-experiment among a sample of US retail investors, we find that individuals who experience incidental guilt are willing to invest more in SRI funds than those in a neutral state. We show that this effect, albeit moderate in magnitude, cannot be explained solely by differences in retail investors’ moral reasoning, attitudes towards social responsibility, risk tolerance and demographic factors. When presented with a trade-off between sustainability, risk and return characteristics of the funds, guilty investors are more willing to sacrifice returns for greater sustainability than non-guilty participants. Our research provides new evidence of the effect that incidental guilt has on the sustainable investing decisions of retail investors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) is an investment style which accounts for ethical values, environmental and social responsibility as well as good governance (ESG) (Berry & Yeung, 2013; Gutsche et al., 2020; Renneboog et al., 2006). SRIs are growing at a rapid pace and have already entered the mainstream of investing activities for both institutional and retail investors around the world (Eurosif, 2016; Sparkes & Cowton, 2004). The surge of SRIs has been predominantly driven by Europe; recent figures show that Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) that are aligned with ESG principles represent 65% of total European ETF inflows in 2022.Footnote 1 In the US, SRIs have also significantly evolved and the majority of the largest US asset managers today incorporate ESG considerations into their portfolio construction process.Footnote 2 However, some substantial outflows have been observed in the US as of late 2022 (nearly USD 6.2bn in Q4 2022). The combined ESG fund assets totalled USD 286bn at the end of 2022Footnote 3 representing only 11% of the global fund assets. However, according to the OECD (2021), the mobilisation and upscaling of private investments are required to meet international climate targets. Most of the asset flows to SRIs come from retail investors who want to make a positive change (Fletcher & Oliver, 2022). A large body of literature explores SRI in the context of institutional investors (e.g. Cumming & Johan, 2007; Sparkes, 2008; Sparkes & Cowton, 2004), while little is known about what drives retail investors towards SRI. The rapid increase in SRI among retail investors calls for research to understand its drivers. It is therefore important to study the determinants of retail investment decisions in SRIs to design appropriate policy measures that could support and incentivize retail investments.

Investing in SRI allows retail investors to express their ethical and environmental concerns through investment decision-making, and for this reason, it is considered a moral behaviour, resulting from moral judgement formation (Pitluck, 2008). Emotional responses are a fundamental element of moral judgement formation and a significant factor in any decision-making process (Haidt, 2001; Tarditi et al., 2020). Several studies investigate emotions in the context of environmental and responsible consumption decisions (i.e. Antonetti & Maklan, 2014; Kals et al., 1999) with a particular focus on moral emotions, as these tend to lead individuals towards social and moral considerations (Baumeister et al., 1994; De Hooge et al., 2011). Among moral emotions, guilt is a powerful motivator of ethical decisions (Steenhaut & Van Kenhove, 2006), and for this reason, is often successfully used in environmental campaigns to promote moral behaviours and motivate individuals towards pro-environmental behaviours (Schneider et al., 2017). Our research contributes to this academic stream of literature by investigating whether incidental guilt can also influence SRI decision-making and direct retail investors towards ethical considerations and investments.

Using survey data from an online quasi-experiment among a sample of US retail investors, we test whether individuals who are feeling guilty invest more responsibly in comparison with non-guilty investors when presented with a set of investment opportunities with varying levels of risk, expected return and social responsibility. Additionally, we explore whether guilt has an impact on the trade-off between profitability characteristics and sustainability that might arise during one’s financial decision-making process in real-world settings. Our survey includes a guilt induction and an investment task alongside several survey questions employed to control for additional factors that impact financial and sustainable decision-making. We induce incidental guilt using an autobiographical recall task to explore its effect on a set of investment decisions, where participants are presented with various combinations of investment attributes (risk, expected return and sustainability label). We also control for individuals’ demographic information, financial literacy, moral reasoning, perceived consumer effectiveness (PCE), social responsibility, risk tolerance and other individual characteristics of retail investors.

We find that in general US retail investors have a strong preference towards ethical funds. Furthermore, our results show that incidental guilt has a statistically significant but moderate impact on their decision-making process. Specifically, our findings reveal that guilty individuals have a higher stated preference towards more sustainable funds in comparison with those in a neutral state even when controlling for their personal characteristics and values relevant to such decisions. Moreover, guilty investors are willing to sacrifice more return in order to avoid making an allocation to an unethical investment option, by choosing a more sustainable fund even if it means giving up a portion of expected return, or increasing the level of risk. When controlling for further characteristics, we find that in addition to the guilty state, investors who are generally more moral, socially responsible, financially literate, risk-averse and convinced that their actions and financial choices have an impact on solving ethical issues have a higher stated preference towards ethical funds, while also willing to pay more for sustainability.

The present study makes several contributions. To our knowledge, we are the first to explore the effects of incidental guilt on SRI decision-making. Several scholars explore the relationship between guilt and prosocial, pro-environmental and consumption behaviours (Chen & Moosmayer, 2020; De Hooge et al., 2011; Haidt, 2003; Steenhaut & Van Kenhove, 2006). However, no previous study investigates the relationship between incidental guilt, and SRI decision-making process. This is surprising, as both involve a significant moral element (De Hooge et al., 2011; Hofmann et al., 2008). We also extend the stream of literature that utilises surveys and stated choice experiments to elicit preferences for sustainable choices, by incorporating three key attributes of investment decisions: risk, return and sustainability label, and relating them to the morality of investors.

Additionally, our research contributes to the stream of literature that explores how emotions and incidental states impact financial decision-making (Lerner et al., 2004; Lo & Repin, 2005; Fenton-O’Creevy et al., 2011). Guilt is an essential moral emotion and it is, to some extent, constantly present in our everyday life (Baumeister et al., 1994). For this reason, the guilt induction implemented in the current study represents one of the common states that individuals find themselves in on a regular basis. We also show that controlling for individuals’ moral reasoning and social responsibility does not moderate the impact that guilt has on SRI choices, which means that the effect of incidental guilt is not conditional on one’s high morality or social values. Hence, our findings also shed light on how everyday incidental emotions impact sustainable investment behaviours and offer a valuable contribution to the understanding of how behavioural motivations drive ethical investments. Moreover, the inclusion of additional variables allows us to further explore how individual characteristics of investors affect SRI choices, contributing to the literature investigating the determinants of individual SRI decision-making (e.g. Bauer & Smeets, 2015; Gutsche et al., 2020; Gutsche et al., 2023; Gutsche & Ziegler, 2019; Rossi et al., 2019; Heeb et al., 2023).

Finally, there has been a number of recent studies investigating the impacts of positive emotions on SRI (Gutsche et al., 2023; Gutsche & Ziegler, 2019; Heeb et al., 2023) and findings show that emotions are able to alter such decisions. Our study extends previous findings as well as provides grounds for further research. We focus on the effect of guilt, a negative moral emotion, on SRI, and extend previous studies on the role that guilt has on the decision-making process (e.g. Antonetti & Maklan, 2014; Chen & Moosmayer, 2020; Steenhaut & Van Kenhove, 2006).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. “Literature Review and Hypothesis Development” section presents a review of the literature and our main hypotheses. “Data and Methodology” section outlines the collected survey data and the methodology implemented, including a description of the survey structure, key variables and the econometric models. “Results” section discusses the results. “Discussion and Conclusions” section presents conclusions and implications.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Retail investors are likely to significantly increase investments when ethical funds outperform conventional ones. However, they are also willing to accept certain performance deviations of SRI funds, which is a clear example of irrational behaviour (Bollen, 2007). The willingness to accept less return for the sake of being ethical contradicts the traditional finance theory of rationality, and its core principle, profit maximisation (Beal et al., 2005). Moral considerations can lead to such inefficiencies in financial markets when they become part of investors’ decision-making (Michelson et al., 2004). Hence, irrational behaviour associated with SRI could arise from the moral judgement component that reflects personal attitudes towards ethical issues. Moral judgement, being a complex process, heavily relies on instantaneous emotional responses to triggers, and unconscious processes named as intuition. Hence, moral emotions could play a role in the outcome of any decision-making process (Herzog & Golden, 2009).

In line with these considerations, various scholars have explored the effects of moral emotions on decision-making in general as well as in social dilemma situations. Moral emotions are also important drivers of prosocial behaviours. General emotions can be defined as individuals’ quick and unconscious behavioural responses to threats and changes in the environment. Moral emotions are instead emotions that impact one’s perception of right and wrong and arise from situations that are linked to morality (Kroll & Egan, 2004). Moral emotions are associated with the interests and wellbeing of others and the society (Haidt, 2003), and affect decisions the most, due to their powerful nature and integration with individuals’ values (Schwartz, 1977). Beal et al. (2005) illustrate these relationships by conducting a meta-analysis on the potential motives of SRI investors. They find that non-pecuniary returns, such as moral satisfaction from doing the right thing, act as a significant driver of prosocial behaviour in the investment context. These non-pecuniary motives provide reinforcement for the feeling of social responsibility and act as a mechanism to generate emotional rewards. This process is also known as “warm glow”, a positive feeling in the form of personal satisfaction, or self-conscious pride, that arises from a morally good act (Ferguson & Flynn, 2016; Tangney & Tracy, 2012).

Feelings of warm glow have positive impact on helping behaviour as well as pro-environmental actions (Dunn et al., 2014; Gorczyca & Hartman, 2017). Gutsche and Ziegler (2019) explore warm glow in the context of ethical decision-making and find that individuals who experience a higher warm glow tend to make more ethical investment decisions when presented with a trade-off between profit and sustainability. In this case, warm glow refers to deriving more utility from the act of giving up a certain amount of possible profits for a good cause, rather than from a potential financial gain. In this sense, warm glow is one of the motivational forces stimulating prosocial behaviour, an example of how moral emotions can impact SRI decision-making.

Nilsson et al. (2016) make a distinction between positive and moral emotions, stating that guilt, a negative emotional reaction to behaving immorally, is the negative equivalent of warm glow. According to Tangney and Dearing (2002), negative moral emotions are likely to be stronger than positive moral emotions. Guilt leads to reparative behaviour and is the most prosocial of moral emotions (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). There is a substantial body of research that relates guilt to environmental and ethical behaviour. Guilt can significantly promote cooperation, charitable giving and pro-environmental behaviour (Basil & Weber, 2006; De Hooge et al., 2011; Harth et al., 2013). Both integral guilt—a negative emotion caused by the event itself—and incidental guilt—a negative emotion generated by an unrelated to the event matter—have a significant positive effect on prosocial behaviour (e.g. Sachdeva et al., 2009; Lerner et al., 2004).

Individuals that feel guilty are likely to seek ways to eliminate this feeling due to the strong negative nature of the emotion (Cotte et al., 2005). Hence, if offered a solution on how to feel less guilty, individuals are likely to act on it. Guilt is a result of ethical dissonance, which is a conflict between a desire to maintain a moral image of oneself and a tempting opportunity to profit from an unethical act (Barkan et al., 2015). When ethical dissonance takes place, it causes a substantial amount of distress to the individual experiencing it. One of the ways that allow individuals to restore their balance to a neutral emotional state is by compensating an immoral act with a moral one. This behaviour is called moral cleansing and mostly comprises unconscious actions that an individual is willing to undertake when her moral dignity is being threatened (Zhong & Liljenquist, 2006). Findings by Sachdeva et al. (2009), who conduct a set of experiments investigating the impact of guilty states on charitable donations, provide evidence for moral cleansing as a means of reducing guilt. Participants are presented with key words and are asked to complete an autobiographical recall task by relating an instance of their life to these key words. This is done to make them consider themselves as immoral. Participants in the negative-traits condition are provided with words such as ‘disloyal, greedy, mean, and selfish’ to induce guilt, in contrast to the words ‘caring, generous, fair, and kind’ in the positive-traits condition. Participants who receive the guilt induction on average donate significantly larger amounts than participants in neutral or positive-traits conditions.

Rees et al. (2015) conduct a set of experiments investigating the role of guilt and other moral emotions in motivating pro-environmental behaviour. Guilt is induced by confronting participants with scenarios describing environmental damages, and each scenario is associated with a specific emotion including guilt. Environmental issues caused by humans are associated with the feeling of guilt. This contributes to further pro-environmental intentions and behaviours. These findings suggest that people do attempt to restore their moral self-image when are feeling guilty and try to compensate for this feeling with moral deeds. In line with these findings, Brunen and Laubach (2022) conduct a financially incentivised experiment investigating the relationship between sustainable consumption and SRI behaviours of clients of three German robo advisors. Among other findings, they show that individuals who have high social values but are unable to fulfil those in their daily life (i.e. consistently exhibiting sustainable consumption behaviours) are likely to invest more sustainably. When engaging with SRI, investors try to compensate for their prior unethical consumption behaviours in order to diminish the feeling of guilt (Brunen & Laubach, 2022), which is in line with the moral cleansing framework. Additionally, Lu and Schuldt (2015) show that negative incidental emotions such as anger and guilt are also able to promote support for specific climate change policies by producing a carry-over effect of incidental emotions and making individuals feel responsible. Hence, we argue that incidental guilt can also have a positive impact on individuals’ engagement with SRI as a way to clear their conscience. We propose that when guilt for an immoral act is induced, individuals will try to compensate for previous wrongdoings by investing ethically. Hence, our first hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1

When presented with a trade-off scenario, where a choice between sustainability and risk/return profile of certain investments is present, investors who experience incidental guilt will have a higher stated preference for a sustainable investment option in comparison with those who do not experience incidental guilt.

The question that remains is whether guilty individuals would be more willing to give up a portion of their potential profit to invest responsibly. Few scholars explore the trade-off between returns and sustainability, and the motives of individuals to engage with SRI. Major findings reveal that those motives and the extent to which investors are willing to act in line with moral values vary significantly indicating heterogeneity among investors (Beal et al., 2005; Berry & Yeung, 2013; Gutsche & Ziegler, 2019). Beal et al. (2005), based on the meta-analysis of the previous literature, classified SRI motives as social, financial, and non-wealth returns.

Berry and Yeung (2013) find that non-monetary motives such as morality, norms, and values have a stronger effect on SRI investment decisions than monetary incentives. Using a stated choice experiment in a form of a postal survey with a sample of UK-based participants, they classify SRI investors into three distinct categories: committed, materialistic and opportunistic. This classification is based on the investment preferences of respondents when presented with a trade-off between monetary gains and ethical investment. Around one-third of the of socially responsible investors sample derive more utility from the increase in financial gain, when compared to the utility of improved ethical performance, while most participants stay dedicated to SRI even with no financial reward to outweigh the utility derived from ethical values. The findings by Berry and Yeung (2013) show that socially responsible investors are much more heterogeneous than is generally assumed, and there are investors who are willing to give up profits to invest in SRI for ethical considerations.

Gutsche and Ziegler (2019) support this view and implement a direct measure for the trade-off between monetary reward and sustainability, Willingness to Pay (WTP), or in this context, willingness to sacrifice return for SRI, using a stated choice experiment on a representative sample of German investors. Their findings reveal a strong stated preference towards SRI as well as a significantly higher WTP among investors with certain characteristics including consideration of social norms and environmental awareness. Their results support the idea that investors differ in terms of how much return they are willing to sacrifice for SRI and provide evidence that individuals are willing to do so. This finding points to the fact that profit maximisation might not be the primary concern of all investors when their moral values are at stake. Individuals who invest in a responsible manner are ready to accept more performance deviations in sustainable investments in comparison with conventional investments, leading to the conclusion that investors simultaneously derive utility from monetary and non-monetary components of the investment process (Lewis & Mackenzie, 2000).

Williams (2007) conduct a study to further explore whether financial gain is not the only determinant of investment behaviour and to see whether organisations’ social goals have an impact on such a decision-making process. This study investigates investors’ attitudes towards SRI using the annual survey of GlobesScan Ltd. in five countries, Australia, Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. Findings show that social aims of the firms are the main driver of most SRI investors rather than financial gains obtained when investing ethically. Lingnau et al., (2022) provide further support for this claim and show that corporate sustainability, together with traditional risk, return and liquidity, has a significant impact on individuals’ willingness to invest (WTI). CSR practices within organisations matter for investors and their motivations are not solely affected by investments’ profitability characteristics.

Despite a growing number of studies showing that monetary gains might not be the only motivation to make financial investments, profit creation is the fundamental principle of any investment, and socially responsible investors are not less interested in profit creation than common investors (Lewis & Mackenzie, 2000). Døskeland and Pedersen (2021), find that, in experimental conditions, a wealth framing might be more effective than a moral framing to encourage SRI investments. This result shows that the trade-off between expected gains and moral values is not a straightforward decision and depends on the extent to which investors are willing to accept lower returns. In line with this finding, Pasewark and Riley (2010), conduct a study where participants express their willingness to invest in bonds issued by tobacco company when a non-tobacco company bond is present as an alternative. The investment decisions taken in their experiment are simultaneously affected by financial and non-financial motives, which further highlight the heterogeneity of SRI investors' motivations.

The studies above present a different perspective on responsible choices and highlight the fact that SRI investors are heterogeneous and there are multiple factors on top of morality that affect ethical decisions. For instance, Brodback et al. (2019) show that the level of risk of a certain investment also affects the degree of ethical decision-making. However, no significant differences are found between investment decisions made by sustainability-focused versus risk-focused investors. According to the classical asset pricing models, risk and return are the main attributes that contribute to individuals’ financial decision-making process, determine their view of investment profiles and are the main constituents of profit-maximisation (Sharpe, 1964). Hence, risk level, as the level of expected return, should be equally considered when making assumptions on whether retail investors would trade off performance for sustainability. Most studies that investigate this trade-off mainly focus on the return aspect of investment performance, except for the research by Brodback et al. (2019). The trade-off between risk, returns and sustainability is a key driver of SRI choices, but little is known about how moral emotions, such as guilt, impact this trade-off. We argue that when presented with different risk/return investment profiles of SRI versus conventional funds, guilty participants are willing to give up a larger proportion of expected returns than non-guilty ones. Hence, our second hypothesis follows:

Hypothesis 2

When presented with a trade-off scenario, where a choice between sustainability and risk/return profile of certain investments is present, participants who experience incidental guilt will trade off more returns for sustainability in comparison with investors who do not experience incidental guilt.

The following section will describe the survey data, the data collection process and the methodology that is implemented to address our research questions.

Data and Methodology

Survey Data

The dataset employed in our research consists of a representative sample of US participants, whose responses are collected via Amazon MTurk between August and November 2019. In line with Hartzmark and Sussman (2019), we do not limit our sample to only ethical investors. Instead, we extend the analysis to the general population to elicit sustainable behaviours, and participants are compensated for taking part in the study.

Amazon MTurk is a widely used crowdsourcing platform among researchers in various fields (i.e. Amos et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2022; Pirson et al., 2017). There is a body of literature on the reliability of the data collected from MTurk, and, taking into consideration comments and implications, only highly skilled workers, who have previously completed a substantial number of tasks on MTurk are selected for the present study. In addition, we apply several exclusion criteria to ensure the reliability of our data. The survey contains attention questions throughout the study to obtain consistent data and prevent issues such as non-differentiation and speediness (Alvarez et al., 2019). Incorrect responses related to attention check questions, not complying with the instructions presented prior to open-ended questions, incomplete response submissions, and failure to provide a unique system-related id vital to identify individual responses are being discarded. To further address the issue of speediness, participants who spend less than approximately 5 min or more than approximately 15 min on the task are also excluded (Greszki et al., 2014). We also discard responses provided by participants that attempt the same task multiple times. Lastly, incomplete responses are also removed. As a result, after excluding 136 survey responses, our final sample consists of 403 fully completed questionnaires.Footnote 4,Footnote 5

Experimental Task

The surveyFootnote 6 is designed to investigate the effects of incidental guiltFootnote 7 on SRI decisions and to determine which other factors and individual characteristics drive willingness to invest in SRI. The experiment is presented as two separate parts that are combined to prevent demand effects.Footnote 8 In the first part of the experiment, we manipulate participants’ emotional state. An introductory statement is included in the survey explaining that the study is conducted for research purposes of the School of Psychology at the X UniversityFootnote 9 to provide a convincing cover story. This is done to conceal the induction and to further prevent additional demand effects. At first, participants are randomly allocated into induction and control groups. A guilt induction in a form of autobiographical recall is performed within the induction group, and the control group has a task to describe their regular activities on a Tuesday morning (Ketelaar & Tung Au, 2003; Conway & Peetz, 2012; Sachdeva et al., 2009). The autobiographical recall used to induce guilt is the most commonly employed procedure in studies that aim to assess the effects of moral emotions on prosocial behaviour, and that has been tested extensively in various settings and with participants from different countries (Rebega et al., 2013; De Hooge et al., 2011; Ketelaar & Tung Au, 2003; Nelissen & Dijker, 2007).

The induction group receives a task to write about an occasion in the last two weeks when they felt guilty, where the minimum number of words is set to be 50 to achieve response effectiveness throughout the questionnaire and ensure the success of the guilt manipulation. Participants in the control group do not receive any emotional induction, and their writing task is neutral on the emotional spectrum. The wording of the recall task employed is an adaptation from the one implemented by Conway and Peetz (2012). To mitigate possible concerns related to whether the recall task does induce guilt and that individuals in the treatment group do indeed have stronger feelings of guilt than individuals in the control group, we checked the content of the answers provided by the ‘guilty’ participants. All of the respondents mentioned guilt-related themes, and examples of their answers can be found in Online Appendix 2. We have also run a pilot study of UK retail investors, confirming the intended effect of induced guilt on the SRI preferences of retail investors. We have excluded further manipulation checks. Psychology literature (i.e. Hauser et al., 2018) mentions that there is a significant risk in including manipulation checks when testing the impact of emotions as the effect might disappear when participants are made aware of their own feelings, as expressing an emotion leads to its reduction. In our study, we are specifically testing the impact of guilt on SRI choices and hence the investment task is intentionally placed straight after the induction. If manipulation checks are included, this might make the effect disappear and hence we would be unable to investigate our hypotheses.

Variables

Dependent Variable

The second part of the experiment consists of an investment task that is designed to measure participants’ investment preferences and willingness to invest sustainably. The experiment is composed of a set of ten stated preference questions that require respondents to select which of the funds, namely Funds A, B and C, they would like to invest in. An introductory statement is also included in prior to the task explaining that the study is conducted for research purposes of The Finance Department of X University similarly to the first part of the study.

Each fund in each question has its own level of risk (low, medium or high), return (5%, 10% or 15%), and sustainability label (green, neutral or red).Footnote 10 Minimising risk and maximising return are assumed to be the main goal of any rational individual making financial decisions (Sharpe, 1964). Hence, the risk and return attributes of the funds in the stated choice experiment are crucial factors affecting the investment decision-making process and are used to assess the importance of the sustainability label in the presence of risk and return. The levels of expected return are selected following Brodback et al. (2019) and Wilcox (2003) with the aim to create a realistic scenario where returns represent plausible market values. Sustainability labels are selected based on the principle of traffic-light labelling (Døskeland & Pedersen, 2019). Traffic-light labelling system is widely used in environmental literature as well as food consumption research (e.g. Thøgersen & Nielsen, 2016; Thorndike et al., 2014). The green colour represents sustainability and can activate pro-environmental thoughts (Pancer et al., 2017). Levels of risk are aligned with Bauer and Smeets (2015) and Brodback et al. (2019).

Figure 1 presents the investment task that participants are asked to complete. A trade-off between the attributes of risk, return and sustainability is present in most of the questions, where, for instance, choosing an option with lower risk means giving up some of the expected return (e.g. question 6) or choosing a higher expected return option leads to making a less sustainable choice (e.g. question 2).

Choice questions. This figure shows a stated choice experiment that participants were presented with. Each question (1–10) has three choice options: Fund A, Fund B and Fund C, while each fund has varying levels of risk, return and sustainability. Risk varies between High, Medium and Low. Expected Return varies between 5%, 10% and 15%. Sustainability labels vary between Red, Neutral and Green

We construct the investment task according to principles of statistical efficiency, response efficiency, and ecological validity.Footnote 11 We employ a fractional factorial discrete choice experiment (DCE) design, a method that allows us to limit the number of items by using a small sample from the full list of possible combinations of fund attributes and levels, while maintaining response efficiency (i.e. Brodback et al., 2019; Gutsche & Ziegler, 2019). This approach aims to keep the statistical efficiency to the highest possible level by making the design balanced and orthogonal, while achieving a balance between the statistical and response efficiency measures (Johnson et al., 2013).Footnote 12

Following this strategy,Footnote 13 the fractional factorial DCE design employed in the experiment has ten items.Footnote 14 The Cronbach alphaFootnote 15 test for the overall investment task consisting of ten choice sets shows an alpha of 0.87, and indicates high reliability and internal consistency of the items. Ecological validityFootnote 16 is achieved by presenting participants with realistic funds’ attributes that are key drivers of investment choices for retail investors and market practitioners. As a result, the DCE used in this research provides a valuable tool to assess various aspects of sustainable choices as well as to determine whether a trade-off between sustainability, risk and return is present and whether it is affected by the incidental guilt manipulation.

Explanatory Variables

Measures of Moral Reasoning and Social Responsibility

As it was mentioned in the previous section, moral reasoning lies at a heart of SRI and hence it is important to control for the effects of the moral traits that respondents possess. Previous research concludes that morality is one of the key drivers of ethical investing (Berry & Yeung, 2013; De Hooge et al., 2011; Hofmann et al., 2008) while also having a significant impact on pro-environmental behaviour (Bhattacharyya et al., 2020). By accounting for moral reasoning, we aim to test whether guilt arising from the emotional induction is on its own able to affect SRI investment decisions or whether guilt only impacts individuals with high moral reasoning skills. We can also observe whether more moral individuals have a higher stated preference towards sustainability. Incorporating moral reasoning serves as a tool to distinguish between the effect of the momentaneous state of guilt and the individual level of moral reasoning in general.

We also control for the extent to which participants are socially responsible in their daily life, as this should also affect their ethical investment decisions. Investors who are concerned with social responsibility in general attach a greater value to SRI in comparison with the ones that are not concerned with it (Barreda-Tarrazona et al., 2011). Similarly, Gutsche et al. (2023) find that environmental values have a significant impact on individual SRI choices, which is economically relevant. Their results show that a person with an average level of environmental affinity would invest significantly more into SRI when compared with an investor whose environmental awareness is low. As a result, two subscales from Penner et al. (1995)’s Prosocial Personality Battery (PPB)Footnote 17 are included: Social Responsibility (7 items) and Moral Reasoning (6 items) scales. Both are presented as a set of statements with response options in the form of a Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree with the labels removed to avoid demand characteristics. Our expectation is that investors with higher moral reasoning and social responsibility scores will have a higher stated preference towards green labels in comparison with those that have lower moral reasoning and social responsibility scores. We further hypothesise that such participants will be willing to sacrifice more return for sustainability.Footnote 18

Perceived Consumer Effectiveness (PCE)

In addition to moral aspects, it is important to account for individuals’ perception of their own impact on solving SRI issues via their direct actions, and indirectly when investing in SRI funds. Moral considerations are crucial for investing in SRI funds, but to act on these moral aspects, investors need to believe that their actions would make a difference and improve sustainability. Following Nilsson (2009), who finds PCE to be a significant predictor of SRI behaviours, we include inventors’ impact considerations in the survey. Other previous studies also find that PCE is a significant explanatory variable of socially responsible (SR) actions (Achchuthan et al., 2016; Ming et al., 2015). We use direct questions on whether a participant believes that his/her actions can help to solve socially responsible issues (Impact), and secondly, whether his/her investment actions can contribute to solving these issues (Investment Impact).Footnote 19 We expect that the more individuals believe that their actions/investment actions can have a positive impact on socially responsible issues, the more return they are willing to sacrifice to make a sustainable choice.

Financial Literacy

Another variable included in the analysis is Financial Literacy, which indicates the extent to which individuals are aware and able to distinguish between basic financial concepts (Klapper et al., 2015), their ability to evaluate financial information (Kempson et al., 2009), and use this information to manage resources efficiently (Knoll & Houts, 2012). Although previous studies report inconclusive results about the impact of financial knowledgeFootnote 20 on SRI preferences (Bauer & Smeets, 2015; Riedl & Smeets, 2017), financial literacy as a broader concept can influence financial behaviours, and has been extensively studied in the SRI context (Martenson, 2005; Nilsson et al., 2016; Rossi et al., 2019). Using a stated choice experiment, Gutsche et al., (2020, 2023) find that financial literacy is positively related to investment amounts in SRI. In line with the findings of Gutsche et al., (2020, 2023), we expect that participants who are more financially literate will have higher stated preference for the green label and will be willing to sacrifise more return for it. We implement the Standard & Poor's Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey (Klapper et al., 2015), which consists of five multiple choice questions.Footnote 21

Risk Tolerance

Participants’ risk attitude is another variable included and is a commonly used attribute of financial decision-making. We use Grable and Lytton’s (1999) 13-items questionnaire to assess participants’ risk tolerance.Footnote 22 Questions range from situational to risk-return probability-weighted scenarios. D’Hondt et al. (2022) conduct a study using both survey and trading data for 9,826 retail investors and find a significant negative relationship between the degree of risk tolerance and social and environmental scores of the stocks held in investor portfolios. One of the primary reasons for considering ESG factors when investing is to be able to minimise risks, while profit maximisation is the primary goal of a rational investor’s decision-making process, which means that it is likely that an investor would associate a green fund with lower risk (CFA, 2020). Hence, we expect that individuals who are more risk-averse will be willing to sacrifice more return for the green label while having a higher stated preference for green investment choices in comparison with participants who are more risk tolerant.

Demographic Data

Several studies explore the profiles of socially responsible investors to identify which demographic traits affect their decisions. We control for age, gender, and income, which are incorporated in the main models. Previous studies do not provide a conclusive result on the relationship between age and SR behaviours (Diamantopoulos et al., 2003). However, few recent works on the relationship of demographic factors and pro-environmental attitudes show a positive relationship between age and pro-environmental actions (Pinto et al., 2011; Swami et al., 2011). Hence, our expectation is that older participants will have a higher stated preference for the green label. Age is measured using a direct question where participants are being asked to indicate their current age, while no participant taking part in the survey is below 18 years old.

Gender is another factor that is related to SRI decisions. Previous findings suggest that female investors tend to show higher engagement with SRI (Gutsche et al., 2023; Laroche et al., 2001; Roberts, 1996). According to Zelezny et al. (2000), this might be because society shapes gender roles, and women are expected to be more empathetic, and cooperative than men, and hence more socially responsible. Our expectation is that women will have a higher stated preference for a green label than males and will be willing to sacrifice more return for it. Additionally, we also control for income in our analysis. Income is one of the most common factors used in studies that investigate green behaviours (Diamantopoulos et al., 2003). We expect higher income to be positively associated with the willingness to sacrifice return for sustainability and to also have a positive impact on the stated preference for a green fund (Junkus & Berry, 2010; Woodward, 2000). Income is measured as a categorical variable capturing the annual income of the respondents.Footnote 23

Econometric Approach

Mixed Logit Model Analysis

In the present study, we aim to address the question whether the impact of desirable sustainability characteristics of an investment option (i.e. green sustainability label) on choice is stronger for individuals that are in a guilty state in comparison with those that are not experiencing guilt. Furthermore, we are attempting to investigate whether such participants who experience incidental guilt via manipulation would be willing to sacrifice more expected return for the green label in comparison with investors who are not subject to a guilt induction (control group). Each individual investor is required to make ten choices between three funds, where each fund has three attributes: level of risk and expected return, which are integral to investment choice, and sustainability labels (green, neutral and red). A mixed logit model is employed to establish the relevance of these attributes and their relative impact on the investment choice. Mixed logit models allow us to identify the attributes or attribute levels driving individual choices in the specific choice situation. In our setting, we use mixed logit models to test whether individuals have a significantly higher stated preference towards a fund with green or neutral sustainability label compared to a fund with a red label.Footnote 24 The relative impact of the fund attributes on the fund choice is based on approximating utility functions for each of the alternatives (Gutsche & Ziegler, 2019), which is a basis for DCE construction (Mangham et al., 2009). This model, in contrast to more standard multinomial logit models, allows for random preference variation and correlation in unobserved factors, a feature relevant for stated choice experiments as it allows to consider correlations between alternatives (McFadden & Train, 2000).

The utility of each respondent i (i = 1, 2, 3…N) for alternative m (m = Fund A, Fund B, fund C) in set of choices p (p = 1,2,3…10) can be expressed as the following function:

where \({X}_{imp}\) is a vector of observed attributes and individual characteristics. \({B}_{i}\) is a vector of unknown corresponding parameter vectors and \({e}_{imp}\) is an independent and identically distributed (IID) error term which summarises all possible unobserved factors for the choice of a fund. To account for the set of individual and demographic characteristics outlined above, we employ a set of interaction terms between those characteristics, the dummy variables for the sustainability labels (green, neutral, red) and the guilt dummy. All the coefficients of the interaction terms included in the analysis are set to be fixed (Goett et al., 2000; Gutsche & Ziegler, 2019). By including interaction terms, mixed logit models further allow us to identify which investors (e.g. in terms of age, gender, or financial literacy) are more or less likely to invest in a fund with a green sustainability label. We further test our hypotheses by including the aggregated dummy variable for the sustainability label in the model specification. This allows us to analyse whether the feeling of guilt would make individuals avoid making an unethical choice (i.e. a fund with a red label) by selecting either a neutral or green fund instead, and to further investigate which individual characteristics have an impact on such choice. After having obtained the data on the respondents' sequence of choices, \({y}_{ip}=m\) and assuming that each individual would choose m only if he is deriving maximum utility from it in comparison with other alternatives, we derive the probability of choosing m using SML estimation with 1000 Halton intelligent draws (Hensher et al., 2005).

Willingness to Pay (WTP) Measure

Following Gutsche and Ziegler (2019), we employ Willingness to Pay (WTP) measure to elicit the magnitude of trade-offs between various choice attributes—i.e. financial and non-financial attributes in order to address the research question of whether guilty participants are more willing to sacrifice return for sustainability. This measure is used extensively in various fields including pro-environmental, consumption behaviour (Dardanoni & Guerriero, 2021; Hensher et al., 2005; Michaud et al., 2013), and corporate disclosure (De Villiers et al., 2021). With the exception of Gutsche and Ziegler (2019), who implement the measure to elicit willingness to sacrifice return for sustainability, WTP has not been extensively used to analyse sustainable investments.

Our estimation of WTP is based on setting the coefficients of expected return as fixed (Gutsche & Ziegler, 2019; Hensher et al., 2005). However, we cannot assume that there is no variation across participants because the utility derived by different investors cannot be quantified. A comparison of variation in marginal utilities of participants would be implausible and, for this reason, we only focus on the ratios of marginal utilities across attributes. Assuming fixed coefficients for expected return and for interaction terms, and random coefficients for the remaining non-financial attributes enables us to estimate mean WTP for each of the random parameter attributes and interactions. WTP is calculated as the ratio between the negative means of the random coefficients and the means of the coefficients of the expected return parameter (Gutsche & Ziegler, 2019).

Summary Statistics

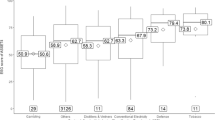

Table 1 represents summary statistics for the average number of green, neutral and red funds chosen across the 10 questions in DCE including a between-group t-test. Panel A represents statistics for the green choices, while Panels B and C show statistics for the neutral and red labels, respectively. It can be seen from Panel A that 48.9% of the total number of participants receive a survey with guilt induction (guilty group), while 51.1% receive a questionnaire with no induction (control group). On average, participants who receive a guilt induction choose green funds 4.9 times out of 10, and the median of the group is 5. Respondents in the control group choose green funds 4.5 times on average and have a lower median than the guilty group (4). This indicates that participants who feel guiltyFootnote 25 make a marginally larger number of sustainable choices than those in the control group. The difference in the mean scores is 0.39, and statistically significant on the 5% level, pointing to a relatively modest effect of guilt on the number of green choices. Moreover, the number of green funds chosen in the guilty group varies between 0 and 10, while the maximum number of green choices that respondents in the control group make is equal to 8.

From Panel B it can be observed that the difference between the average number of neutral funds chosen across guilty and non-guilty groups is not significant with a median score for both groups being 3. However, Panel C shows that in line with the findings regarding green choices, guilty participants choose significantly fewer red funds on average. Specifically, the average number of red funds chosen among guilty individuals is 0.34 lower than that of participants from the non-guilty group and the difference is significant on the 5% level. These observations point to a generally small shift of the distribution for the guilty group towards a higher number of times that the green fund is chosen and a lower number of times that the red fund is chosen with respect to the non-guilty group.

Table 2 below shows summary statistics for the explanatory variables. Panel A represents the statistics for all participants, while Panels B and C present the statistics for guilty and non-guilty groups, respectively. Panel D presents a series of between-group two-sided t-tests used to establish whether there are any significant differences between groups with regard to the values of the explanatory variables.

Panel A shows that the average participant in our sample is 46 years old, has moderate risk tolerance and is financially literate in line with Klapper et al. (2015).Footnote 26 Male and female investors are almost equally represented (48% and 52%, respectively). The median result for financial literacy in our sample is 3 overall as well as in each of the groups (Panels B and C). In terms of group-specific traits (Panels B and C), participants in both groups seem on average more inclined to believe that their actions as well as investment decisions have an impact rather than otherwise. Specifically, both guilty and non-guilty groups score 3 on average for both questions, while the scale is ranging between 0 and 4. For moral reasoning and social responsibility, the median score is 23 for both groups, while variables range between 8 and 30 and between 10 and 35, respectively. Additionally, Panel D shows that there are no significant differences between guilty and non-guilty groups across all control variables aside from risk tolerance, where it seems that non-guilty participants are slightly more risk tolerant than guilty ones. The difference is equal to 0.17 and is significant on the 10% level. It has been documented in the literature that risk tolerance increases when positive emotions are triggered while decreasing when negative emotions are present (Brooks et al., 2023). This marginal difference in risk tolerance could potentially explain the weakly significant difference between the two sub-samples, because the risk tolerance task is presented to participants after the guilt induction, implying that guilty investors might take less risk as a byproduct of the manipulation.

According to Spearman’s correlation matrix in Table 3, there is a significant 9.7% correlation between green choices and the guilt induction dummy. A positive relationship indicates that participants in the guilty group choose more green funds than participants in the non-guilty group. Similarly, a significant negative correlation coefficient of 9.7% between the number of times participants chose a red label and guilt shows that guilty participants choose fewer red funds, confirming results from summary statistics and in line with our expectations. We also find a significant positive relationship between age and the number of green choices made alongside with a negative relationship between age and the number of red choices made. As participants get older, they make more responsible choices and consequently choose more green-labelled funds. Female is significantly positively correlated with the average number of green funds chosen and negatively correlated with the average number of red funds selected with coefficients showing that females are more inclined to make sustainable choices than males. Moral reasoning and social responsibility have a positive significant correlation with the variable green choices and a negative significant correlation with the average number of red choices made, confirming the expectation that investors with higher moral reasoning and social responsibility prefer green funds. Financial literacy is significantly positively correlated with the number of green funds chosen (29%). In addition, risk tolerance has a significant negative correlation with the number of green choices made (− 19%). Finally, impact and investment impact are both significantly positively (negatively) correlated with the number of green (red) choices made.

Results

The Impact of Guilt and Fund Attributes on SRI Choices

Table 4 displays the parameter estimates for the mixed logit models with robust Z-statistics and the mean WTP for the choices among Funds A, B and C with green and neutral sustainability labels, expected return and the level of risk. The estimation is based on 403 participants (403 × 10 × 3 = 12,090 observations as per model specification). Across all regressions, the standard deviations of the random parameters are statistically significant, which means that unobserved heterogeneity is present among participants.Footnote 27 Column (1) shows that both neutral and green labels have a significant positive impact on the choice between funds A, B and C, meaning that in general participants have a higher stated preference for such funds in comparison with the ones with the red label. Moreover, it can be observed that participants also prefer to obtain higher expected returns, while minimising the level of risk, which aligns with the traditional finance theory of a rational man (Sharpe, 1964).

The means of the parameters in mixed logit models can be interpreted in terms of their signs; however, the size of the effect cannot be directly established without further analysis. For this reason, the lower part of Table 5 represents the mean WTP estimation, used to gauge the economic size of the estimated effects. In column (1), the mean WTP for the green label is 1.76 percentage points higher than for the red label, which shows that in general participants are willing to sacrifice returns for the green label and hence their preference for such investments is strong, in line with previous findings (i.e. Bauer & Smeets, 2015; Gutsche & Ziegler, 2019; Nilsson, 2009). Similarly, the mean estimated willingness to sacrifice return for the neutral label is 1.14 percentage points higher than for the red one, which is even higher than WTP for a lower level of risk (0.89 percentage points), indicating strong preference and willingness to sacrifice returns for the neutral label over the red one, which represents undesirable ESG characteristics.

Column (2) includes two additional variables, which represent interaction terms between the dummy variable guilt with green and neutral labels, respectively. Both are significant on the 1% level, indicating that guilty participants have a higher stated preference for both green and neutral labels. Our findings show that investors who experience incidental guilt have a higher stated preference for sustainable funds in comparison with those who do not experience incidental guilt. Furthermore, the lower part of Column 2 shows that guilty individuals are willing to sacrifice 0.54 and 0.33 percentage points more expected return for green and neutral labels, respectively, in comparison with non-guilty ones. This latter finding highlights the significant—albeit relatively moderate—impact that incidental moral emotions (i.e. guilt) have on investment decisions while motivating individuals to clear their conscience via investing sustainably.Footnote 28

The Impact of Guilt and Individual Characteristics on SRI Choices

Table 5 represents the SML estimation results for mixed logit models incorporating fund attributes (dummy variables for the sustainability labels, risk and expected return) as well as interaction terms between the sustainability labels and additional individual characteristics including age, gender, moral reasoning, social responsibility, financial literacy, income, risk tolerance, impact and investment impact. Column (1) shows the parameter means, Column (2) represents standard deviations of the random parameters, and Column (3) depicts the mean WTP estimates for the variables of interest. Due to the inclusion of interaction terms in this model specification, the interpretation of the parameter means for the sustainability labels (green and neutral labels) on their own only refers to a case when all interaction terms are equal to zero. For this reason, our analysis focuses on the mean parameter estimates and WTP for the interaction terms between the labels and individual characteristics. We find that these interaction terms are statistically significant predictors of the stated preference for the green and neutral labels among participants.

When controlling for such individual characteristics, guilty participants still exhibit a significantly higher stated preference for a green label in comparison with non-guilty ones, while the mean WTP for guilty participants is 0.41 percentage points higher than for the ones who are not experiencing guilt, confirming our Hypotheses 1 and 2 related to the impact of guilt on preferences towards green funds and higher WTP for guilty investors. These findings are in line with existing literature on the effect of moral emotions on prosocial (Sachdeva et al., 2009) and pro-environmental (Rees et al., 2015) behaviours, and show that the mechanism of moral cleansing can also be applied to the investment settings.

The parameter mean estimate for the interaction between neutral label and guilt is not significant, due to the presence of other control variables incorporated in the model. Specifically, it can be noticed that the mean parameter estimate for the interaction term between age and neutral label is significant, while the interaction term between age and green label is not. In other words, older participants have a higher stated preference and are willing to sacrifice more return for a neutral label, but not for the green label. Generally, earlier studies show conflicting evidence on the relationship between age and SRI, which lead Diamantopoulos et al. (2003) to conclude that younger and older participants differ in terms of how they take part in green activities. The rationale behind it is that younger people tend to display intended SRI behaviour, while older individuals show current SRI behaviour (Scott & Willits, 1994). Hence, it could be possible that, by choosing a neutral fund, older participants are able to express their SRI behaviour in real life.

Additionally, interaction terms between impact and investment impact with the sustainability labels show that individuals who believe in their own impact on solving ESG issues have a higher stated preference for a neutral fund, while those who believe that their investment actions have such impact have a higher stated preference for a green label, with mean WTP being 0.20 and 0.22 percentage points higher in comparison with the red label, respectively. This aligns with previous findings that perceived impact is a significant motivator for ethical investing. If retail investors do not believe that their actions can make a difference, they will not invest in SRI, even if they support the underlying cause (Nilsson, 2009). In line with our expectations, more moral and socially responsible investors have a higher stated preference for sustainable funds and are willing to sacrifice more returns for both green and neutral labels (e.g. Barreda-Tarrazona et al., 2011; Berry & Yeung, 2013).

Investors with higher financial literacy also have a significantly higher stated preference for both neutral and green labels and are willing to sacrifice 0.38 and 0.67 more return for such funds in comparison with the red ones. Our findings align with Gutsche et al. (2020), who also find a significant positive relationship between financial literacy and stated choice SRI preferences. We also document a significant negative relationship between risk tolerance and stated preference towards sustainable funds. More risk-averse participants are willing to sacrifice 0.05 percentage points more expected return for a neutral label and 0.07 percentage points more return for the green label, which aligns with findings by D’Hondt et al. (2022).

Aggregate Sustainability Label and SRI Choices

So far, we have observed that a guilty conscience influences SRI decisions and investors’ willingness to sacrifice return for sustainability, even when accounting for several individual characteristics of investors, supporting our hypotheses. Table 6 displays the parameter estimates for mixed logit with robust Z-statistics and the mean WTP for the choices among Funds A, B and C with the aggregated sustainability label, used instead of individual neutral and green labels, the level of expected return, risk, and the individual characteristics of retail investors described earlier. Here we explore whether those characteristics individually influence the willingness to sacrifice return for SRI. Following Gutsche and Ziegler (2019), we incorporate the aggregated dummy variable for the sustainability labels. This way we are able to derive the aggregate values for willingness to pay for sustainability instead of considering separate sustainable labels, namely the neutral and green labels. We aim to better understand how much return investors are willing to sacrifice to avoid making an unethical choice (i.e. choosing a red fund) on average, and explore which individual characteristics have an impact on such choice.

The analysis predominantly focuses on the interaction terms between guilt and sustainability, as well as interaction terms between the additional individual characteristics and the aggregate sustainability label. The main finding is that the interaction term between guilt and the aggregated variable for the sustainability label is significant, confirming that guilty individuals have a significantly higher stated preference towards a more sustainable label, which can be observed across Columns (1–10). This further supports our Hypothesis 1 and shows that when controlling for additional variables, investors that are in a guilty state are more inclined towards a more sustainable choice in contrast to choosing a fund that has a negative sustainability label. Moreover, the mean WTP for the sustainability label is consistently higher for guilty participants providing further support for Hypothesis 2. It is also important to note that the magnitude of this difference is economically significant. Apart from high financial literacy and gender in Column (3), the difference in the mean WTP for sustainability between guilty and non-guilty participants is the highest across all variables.

Furthermore, Columns (2), (3) and (4) further confirm our findings with regard to age, while Columns (2–6) show that female investors have a higher stated preference towards a more sustainable choice and are willing to sacrifice more return to make ethical investments. This is in line with the positive correlation between the variable Female and Green Label discussed in Sect. "Summary Statistics" as well as being in line with the literature findings, which indicate that women tend to exhibit significantly more pro-environmental behaviours than men (Hunter et al., 2004), and engage more with SRI (Nilsson, 2009). Column 10 represents estimated coefficients and WTP for all variables of interest and shows that guilt, moral reasoning, social responsibility, financial literacy, risk tolerance and investment impact have the strongest influence on the stated preference towards making a sustainable choice, which is in line with our expectations and hypotheses as well as previous findings in the literature.Footnote 29

Number of Green Choices: Poisson Regression Model

The main focus of the paper is to gauge the impact of guilt on SRI decision-making and to explore whether guilty investors would be willing to invest more in sustainable funds. For this reason, we provide a complimentary analysis in search of further confirmation of our results. In this analysis, we intend to measure the number of times participants choose a green fund, and a count data model is the most suitable to perform such an investigation (Gutsche, 2019). We employ a Poisson regression model, with robust standard errors to control for heteroskedasticity and normality, to explore whether guilt and individual characteristics of retail investors have an impact on the number of green choices made among participants.

The dependent variable is a count variable Green Choices, which can take values between 0 and 10, indicating the number of times a fund with the green sustainability label is chosen by each retail investor i out of 10 tasks. The main explanatory variable is a dummy variable Guilt, which can take values 1 or 0 depending on whether the guilt induction is performed or not. The model is specified as follows:

where \({\alpha }{\prime}\) is a vector of constant terms, εi is a standard normal error term, \({Guilt}_{i}\) is the guilt induction dummy variable, \({Age}_{i}\) is participants’ age measured in years, \({Female}_{i}\) is a dummy variable of participants’ gender, taking the value of 1 if the gender is female, and 0 otherwise. \({MoralReasoning}_{i}\) and \({SocialResponsibility}_{i}\) are count variables that proxy for the personal degrees of moral reasoning and social responsibility and are measured in scores ranging from 6 to 30 and from 7 and 35. \({Income}_{i}\) is a categorical variable that can take values between 0 and 15 depending on the income bracket. \({FinancialLiteracy}_{i}\) is a count variable ranging between 0 and 4 depending on participants’ financial literacy score, representing low to high financial literacy. \({RiskTolerance}_{i}\) is a count variable with values between 13 and 47, indicating low to high risk tolerance of the investors. \({Impact}_{i}\) and \(Investment{Impact}_{i}\) are count variables ranging between 0 and 4.

Table 7 presents the parameter estimates for the Poisson regression model incorporating all additional variables explored in the previous section. Guilt has a statistically significant impact on the number of green choices made, at 5% and 10% levels across Columns (1–12). Moreover, the remaining results are qualitatively similar to the previous analysis, with the exception of age which is not significant. With regard to gender, it can be observed that variable Female has a statistically significant relationship with the number of green choices made in all regressions except (6). This provides further evidence of the impact that gender has on SRI choices.

Our earlier findings related to financial literacy, risk tolerance, moral reasoning, social responsibility, impact, and investment impact are also confirmed. Interestingly, this model reveals a significant impact of income on the number of green choices made, which did not have any significant explanatory power over the choice between funds A, B and C in the mixed logit analysis. The finding that investors with higher income tend to make more green choices is in line with research that investigates demographics in the context of SRI (i.e. Cheah et al., 2011; Junkus & Berry, 2010). However, Poisson regression models do not consider additional fund attributes incorporated in the DCE (i.e. level of risk and return), and results can be prone to omitted variable bias. Hence, we mitigate this concern by using mixed logit models as our main econometric estimation technique, taking into account all fund attributes and levels.

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper empirically examines whether incidental guilt can influence investors' decisions to invest in Socially Responsible Investments, among a sample of US retail investors. We also elicit willingness to pay (WTP), a measure of the extent to which investors are willing to sacrifice return for sustainability. We posit that guilty investors would prefer SRI funds and are likely to sacrifice more return to invest sustainably than non-guilty ones. To address our hypotheses, we conduct a survey with an online quasi-experiment, which consist of an incidental guilt induction, one investment task in the form of a newly designed stated choice experiment, questions that control for variables relevant to financial and socially responsible decision-making, and the demographic characteristics of respondents. We conduct a mixed logit analysis that documents a statistically significant relationship between induced incidental guilt and stated preferences for the sustainability labels (namely green and neutral labels) as well as higher WTP among guilty investors. Individuals who feel guilty have a significant preference towards green funds and are willing to sacrifice more return to invest sustainably in comparison with participants who do not feel guilty, supporting literature findings on the impact of guilt on charitable giving, prosocial and pro-environmental behaviours (i.e. Lu & Schuldt, 2015; Rees et al., 2015; Sachdeva et al., 2009). After controlling for additional variables, we show that the effect of incidental guilt on SRI choices is still significant, albeit relatively moderate in magnitude, and that this relationship is not conditional on the level of moral reasoning, social responsibility and other individual characteristics.Footnote 30

These findings provide grounds for further research in the domain of moral emotions with regard to Socially Responsible Investing and Corporate Social Responsibility. Guilt is an extremely powerful moral emotion able to alter and/or motivate specific behaviour (Rees et al., 2015), which leads to the question of whether other moral emotions would have a similar impact on socially responsible decision-making. We also find that more financially literate, more risk-averse, socially responsible individuals, with a higher degree of moral reasoning, who believe in the (environmental) impact of their actions and investment decisions are willing to sacrifice more return for sustainability. These findings align with Basil and Weber (2006) who show that moral values are core for ethical consumers when deciding whether to buy a product from a company that is involved in SRI and confirm the results of earlier studies that explore determinants of SRI among retail investors (i.e. Berry & Yeung, 2013; Gutsche & Ziegler, 2019; Gutsche et al., 2023; Ming et al., 2015).

Our findings have important implications for fund marketers, financial advisors, retail investors, and policy-makers, as well as being relevant for the practice of ethics in business. With regard to our main finding, namely the impact of guilt on sustainable choices, we show that similarly to charitable giving settings, a moral cleansing mechanism might at times become activated among retail investors who are feeling guilty while making allocation decisions. These insights can be applied in a fund marketing context to promote sustainable investment practices and in advisory settings, similar to certain charitable marketing campaigns. Firstly, we reveal that incorporating emotional messages in marketing materials for SRI is likely to be an efficient way to promote green investments. Aligning with this approach, guilt appeals are widely adopted in marketing settings and are found to have a significant positive impact on charitable donations (Hibbert et al., 2007; Adomaviciute & Urbonavicius, 2023). However, practitioners should reflect on whether manipulating incidental guilt to grow SRIs is actually ethical in itself. Given that guilt, a negative emotional state, is indirectly influencing the decision to invest ethically (via a cross-over effect), exploiting this mechanism to incentivize sustainable investments could be perceived as unethical (e.g. Antonetti & Maklan, 2014). Moreover, the heterogeneity of retail investors’ attitudes towards sustainability, which we highlight by incorporating individual traits and showing their extent in different degrees of willingness to sacrifice returns for sustainability, signals that not every individual is likely to respond to sustainability-linked nudges in a similar manner. Hence, targeting groups of retail investors depending on their individual characteristics is likely to be a more effective way to promote SRI.

Our findings also have implications for financial advisors when meeting with retail investors. Advisors need to be aware of the impact that the moral emotional states of their clients may have on their investment decisions. Experiencing a specific incidental emotion before meeting with their financial advisors may unintentionally affect the investment decisions that a client makes. The sort of mood of the client before or during the meeting with the financial advisor could influence the investment choices. Indeed the completion of a risk profiling questionnaire usually takes place at the very beginning of the session, when incidental emotional states are likely to play a role in the responses provided by the client (Brooks et al., 2023).

One way to mitigate this could be incorporating an emotional state assessment prior to any investment decision-making taking place with their clients. This would, however, involve additional transaction costs in the process. Moreover, the emotional state assessment might not be adequately performed by financial advisors who are not professionally trained in the emotional profiling of retail investors, leading to additional risks and costs related to the advisory process. Training on emotion regulation could also be beneficial for investors (Brooks et al., 2023). Indeed, individuals that cognitively rationalise emotions tend to be better decision-makers than those that just suppress them (Heilman et al., 2010), leading to more rational investment decisions.

Furthermore, to encourage sustainable investing, policy-makers should recognise the role of individual characteristics and emotional states and their impact on such investment decisions. For instance, the fact that financial literacy has a strong impact on SRI choices means that in order to invest sustainably, retail investors need to have a clear understanding of the available information related to the alternative investment options presented to them by financial advisors or indirectly via investment memorandums and acquire familiarity with key fundamental investing concepts. Promoting financial education and literacy could also indirectly support the understanding and development of SRI (Gutsche et al., 2020). Furthermore, taking into account our findings related to the individuals’ perception of investors’ own impact on solving SRI issues via their direct actions, and indirectly when investing in SRI funds, policy-makers and companies should make the information on the actual impact of SRI more transparent and measurable, so that individual investors are able to recognise, quantify and monitor the impact that their investment decisions have on ESG issues (i.e. net-zero transition, reduction in the amount of CO2 emissions), and further incentivise sustainable investing in the long-run.

Lastly, we intentionally study the effect of incidental guilt on SRI decisions rather than integral guilt. This choice is motivated by the observation that incidental emotions are applicable to several real-life situations, not only to SRI and financial decision-making. Based on the psychological literature on emotions discussed in this research, and the empirical evidence for the relationship between incidental guilt and SRIs, we believe that by changing the guilt emotion induction to an integral guilt induction, the effect of integral guilt on SRI choices would be stronger.Footnote 31 This latter investigation is beyond the scope of our study, but it would be interesting for future research to examine whether integral guilt has the expected stronger impact on sustainable investment choices of retail investors. Some companies and fund marketers might consider it less controversial to induce integral guilt rather than incidental guilt. For instance, an integral guilt manipulation could require fund marketers, companies or financial advisors to provide retail investors with factual information on the negative impact that humans and polluting companies have on the environment and society (e.g. carbon emissions, water scarcity, gender equality), and hence promoting SRI investments that are effective to mitigate such negative impact (e.g. investments on companies that actively engage with initiatives that reduce carbon emissions and/or favour of green energy alternatives). However, also this latter option entails a conundrum, namely whether to manipulate a negative integral emotion—a business practice that could be perceived as unethical—in order to induce ethical behaviours and grow SRI investments.

Notes

Boyde, E. (2023). ESG accounts for 65% of all flows into European ETFs in 2022. Financial Times. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.ft.com/content/a3e9d87f-fa6f-4e5e-be6e-e95b42af2fec.

Boerner, H. (2021). The Surging Volume and Velocity of ESG Investing. NIRI. Retrieved July 15, 2023, from https://www.ga-institute.com/fileadmin/ga_institute/Articles/Surging_Volume_and_Velocity_of_ESG_Investing.pdf.

Kenway, N. (2023). Global Sustainable Flows Bounce Back in Q4. ESG Clarity. Retrieved July 15, 2023, from https://esgclarity.com/global-sustainable-flows-bounce-back-in-q4/.

106 pilot responses from UK retail investors were collected in June 2019, but these responses are not used in the present analysis. This pilot study enabled us to test the survey construction, test the guilt induction, and achieved qualitatively similar findings. The results of the pilot study are not reported for brevity.

The survey is provided in full in Online Appendix 1.

Exploration of other emotional states and their effects are left for further research.

Demand effects are possible changes in participants’ behaviour due to cues of the behaviour they are expected to exhibit (Zizzo, 2010). In our setting, the study is divided in two parts so that the participants do not realise the link between guilty conscience and SRI.

We use the wording ‘X University’ in the manuscript in order not to identify ourselves during the peer review process. In the actual study, the name of the university was outlined in full.