Abstract

Purpose

Clinical guidelines’ (CGs) adherence supports high-quality care. However, healthcare providers do not always comply with CGs recommendations. This systematic literature review aims to assess the extent of healthcare providers’ adherence to breast cancer CGs in Europe and to identify the factors that impact on healthcare providers’ adherence.

Methods

We searched for systematic reviews and quantitative or qualitative primary studies in MEDLINE and Embase up to May 2019. The eligibility assessment, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment were conducted by one author and cross-checked by a second author. We conducted a narrative synthesis attending to the modality of the healthcare process, methods to measure adherence, the scope of the CGs, and population characteristics.

Results

Out of 8137 references, we included 41 primary studies conducted in eight European countries. Most followed a retrospective cohort design (19/41; 46%) and were at low or moderate risk of bias. Adherence for overall breast cancer care process (from diagnosis to follow-up) ranged from 54 to 69%; for overall treatment process [including surgery, chemotherapy (CT), endocrine therapy (ET), and radiotherapy (RT)] the median adherence was 57.5% (interquartile range (IQR) 38.8–67.3%), while for systemic therapy (CT and ET) it was 76% (IQR 68–77%). The median adherence for the processes assessed individually was higher, ranging from 74% (IQR 10–80%), for the follow-up, to 90% (IQR 87–92.5%) for ET. Internal factors that potentially impact on healthcare providers’ adherence were their perceptions, preferences, lack of knowledge, or intentional decisions.

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of breast cancer patients are not receiving CGs-recommended care. Healthcare providers’ adherence to breast cancer CGs in Europe has room for improvement in almost all care processes. CGs development and implementation processes should address the main factors that influence healthcare providers' adherence, especially patient-related ones.

Registration:

PROSPERO (CRD42018092884).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Clinical guidelines (CGs) are defined as “systematically developed statements to assist healthcare providers and patients’ decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances” [1]. These recommendations are intended to optimise patient care, reduce inappropriate practice variation, enhance the transition of research into practice, and improve healthcare quality and safety [2]. Despite the availability of CGs with different presentation formats, a constant production or updating process, their uptake, adherence, or compliance by healthcare providers is variable [3], and sometimes reported as suboptimal [4,5,6]. For example, it has been estimated that only 50% of patients in the United States receive CGs-compliant healthcare [4].

Shared decision-making may be influenced by the complexity of cancer care (e.g. tumour related features), patient’s characteristics, and limitations in the evidence base [5]. Barriers to healthcare providers’ adherence to CGs could be personal barriers, as the healthcare provider’s knowledge (lack of awareness or familiarity with CGs) and the provider’s attitude towards change in practice, and external barriers (the type of guideline, patient, or environment) [6]. A better understanding of barriers to CGs adherence might help healthcare providers comply with CGs recommendations, thereby improving the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care [7].

In 2018, over 400,000 incident breast cancer cases were estimated in Europe [8]. Because of the high burden of the disease and the enormous health-economic impact [9], several breast cancer CGs in Europe have been developed, reflecting decades of intensive research [2]. However, their methodological quality, evaluated with the AGREE II instrument [10], reported low scores for the “rigour of development” and “applicability” domains. The latter includes guideline implementation and resource implications [11]. Despite adherence to breast cancer CGs in Europe being associated with better survival outcomes [12, 13], healthcare providers’ adherence in usual care has not been systematically explored yet. The objective of this systematic literature review is twofold: (i) to evaluate the extent of healthcare providers’ adherence to breast cancer CGs in Europe, and (ii) to identify the barriers to CGs adherence from their perspective.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review [14] and used the PRISMA guidance for its reporting [15]. PRISMA checklist is provided in the Additional file 1. We registered the research protocol in PROSPERO (CRD42018092884).

Information sources and search strategy

We designed the search strategy and conducted the electronic searches, for both systematic reviews and primary studies, in MEDLINE (accessed through PubMed) and Embase (accessed through Ovid), from inception to May 2019. The strategy searched for terms related to adherence, clinical guidelines, and breast cancer. Search strategies are outlined in Additional file 2. Reference sections from retrieved systematic reviews were used to identify additional primary studies.

Eligibility criteria and selection of studies

We sought for primary studies conducted in European countries. The addressed population was healthcare providers of breast cancer care (including primary care, oncology, radiotherapy, or others). Selected studies should measure the adherence of healthcare providers’ indications to breast cancer CGs, with any method (quantitative or qualitative) or source of data (self-reported, medical records’ assessment, interviews) or explore the barriers to adherence from healthcare providers’ perspective.

The extension of assessment could be only one recommendation or a complete guideline. We sought for studies reflecting usual care conditions. We excluded studies assessing patients’ adherence to treatment or indications, clinical trials, or studies to implement programmes to improve CGs adherence. One author (IR) screened titles and abstracts to select potentially relevant references to be evaluated on full text. Then, two authors (AVM, ENDG) independently assessed whether these studies met the eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. We managed references with Endnote version X7 software (Thomson Reuters, New York, USA).

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

We used tabular formats to extract main study characteristics (e.g. country, publication year, objective, year of study data, name of the guideline, guideline scope, adherence definition, number of patients, and patients’ characteristics). Primary outcomes were the proportion of patients receiving breast cancer adherent care according to CGs recommendations, by treatment modality, and the factors that impact on provider’s adherence.

We applied risk of bias assessment tools based on the study design: the AXIS tool for cross-sectional studies [16], the Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies with No Control Group for non-controlled before-after studies [17], the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for prospective and retrospective cohort studies [18], and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for the qualitative study [19]. We followed each tools’ recommendations for the risk of bias assessment. The AXIS tool [16] assigns 0 to 10 scores and has three categories: low (1–4), moderate (5–7), and high (8–10). The Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies With No Control Group [17] includes 12 criteria, and three final categories: good, fair, or poor. The Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale [18] uses scores from 0 (the highest risk of bias) to 9 (the lowest risk of bias). And, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) [19] includes ten domains, with three possible answers: “yes”, “can't tell”, and “no”.

Six authors (AVM, IR, ENDG, JP; MR, YS) were involved in the data extraction and risk of bias assessment. One author extracted data, and then two authors (YS, ENDG) contrasted the accuracy of data against full texts, cross-checked the risk of bias assessment, and completed missing information. Disagreements were solved by discussion or with the help of a third author (IR).

Data synthesis and analysis

We considered inappropriate pooling quantitative findings due to the high variability in adherence definitions and healthcare processes assessed. Instead, we summarised results in a narrative synthesis, for which we defined and categorised breast cancer care as follows:

The overall breast cancer care: the whole healthcare process from diagnosis to follow-up

The overall treatment process: primary and adjuvant therapy (if applicable) including surgery, CT, ET, and RT. Follow-up procedures not included.

Systemic therapy: comprising both CT and ET

Pre-treatment procedures/diagnosis: staging and HER2 status assessment before the treatment process

Surgical procedures: breast-conserving surgery (BCS), mastectomy (MA), sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), axillary lymphonodectomy (ALND), or other surgery recommendations, either assessed separately or as a group.

Therapies (assessed independently): CT and associated therapies (e.g. antiemetics); ET; Targeted anti-HER2 therapy; or RT

Supportive measures during therapies: defined as any therapy aimed to prevent side effects for specific treatments

Follow-up/monitoring: consultations or procedures after receiving treatment with monitoring purposes

Primary prevention strategies: interventions to promote early diagnosis of breast cancer in asymptomatic patients.

We grouped findings based on similarities of treatment modality. To summarise the proportion of adherence, we calculated descriptive statistics (the median, Interquartile range (IQR) (including the median), and range). Data analysis included estimating if possible the overall adherence when reported disaggregated (e.g. as subgroups); selecting the least restrictive definition when several definitions were reported; and selecting the most recent publication or the one with the longest period for studies with more than one publication with a similar objective. To explore barriers to adherence, we summarised the main findings from quantitative studies reporting factors that were significantly associated with non-adherence, and narratively integrated these findings with the qualitative findings. We classified them as internal or external (related to healthcare providers or not). We explored sources of heterogeneity by the source of data (i.e. self-reported or medical records based), treatment modality, and subtype of tumour. We used Microsoft Excel for data analysis. For data reporting, we present tabular summaries and graphical representations.

Results

Study selection

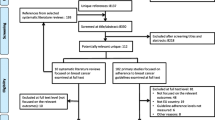

Our search yielded 10,558 references. After removing duplicates, 8137 references were screened based on titles and abstracts. Of these, 102 references were selected for full-text appraisal. We finally included 57 references representing 41 primary studies. Three studies were reported in more than one publication: BRENDA I [12, 13, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], BRENDA II [29,30,31], and OncoDoc2 [32,33,34]. (Fig. 1). Excluded studies alongside their exclusion rationale are available in Additional file 3.

Study characteristics

Included studies were published between 1997 [35] and 2019 [36, 37]. These were conducted in eight European countries, with two countries leading in frequency: The Netherlands (n = 13, 31.7%), and Italy (n = 8, 19.5%). Most followed a retrospective cohort design (n = 19; 46.3%), the remaining included cross-sectional studies (n = 13; 31.7%); non-controlled before-after studies (n = 5; 12.2%); prospective cohorts (n = 4; 4.9%); a case study (n = 1; 2.4%), and a qualitative study (n = 1; 2.4%).

Two cross-sectional studies were based on a national audit [38, 39]. Still, they reported findings for two different subpopulations. Similarly, eleven retrospective studies used data from the National Cancer Registry of the Netherlands but analysed different regions or periods [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50].

Most studies (n = 36, 87.8%) assessed adherence based on medical records (from hospital databases, specific registers, or national cancer registries), and their sample sizes ranged from 131 [51] to 104,201 records [44]. The remaining five studies (12.2%) were based on self-reported data, through surveys or interviews to healthcare providers [52,53,54,55,56], and their samples sizes ranged from 10 [56] to 202 participants [53]. Adherence to CGs recommendations was the primary outcome in 38 studies (92.6%), while three focused on factors that influence adherence [32, 47, 56]. Sixteen studies (39.0%) measured adherence to CGs for more than one process of care (Table 1, Additional file 4).

Thirty-one studies (75.6%) reported how researchers measured the adherence to CGs. Most of these studies (22/31, 71%) assessed adherence contrasting healthcare providers’ indications for breast cancer patients against a selection of CGs recommendations. Six studies (6/31, 19.4%) addressed adherence as a process indicator integrated in the quality assurance programme of their institution [57,58,59,60,61,62]. In three studies (3/31, 9.7%), a “tumour board”, or a multidisciplinary team of physicians, was involved in the clinical pathway of treatment decision [29, 31, 32, 63]. The definitions of adherence were variable across studies. They included one or more of the following components: non-adherence definition, classification for non-adherent treatment, threshold criterion, reference to the currency of guideline, or to the relevance of patients’ profile (Additional file 5).

Risk of bias

We assessed the risk of bias for 40 studies; the case study [32,33,34] was not considered as suitable for this assessment. Most were at low (25/40, 62.5%) or moderate risk of bias (14/40, 35.0%). Only one study (1/40, 6%) was considered to be at high risk of bias, mainly due to concerns regarding selection bias in data analyses [64] (Table 1, Additional file 6).

Adherence to breast cancer CGs recommendations for healthcare processes

Main findings reported by treatment modality, and clinical guidelines are available in Table 2 and Fig. 2.

Median adherence proportions for overall breast cancer care and individual therapies. The square inner line represents the median, while the upper and lower borders, the interquartile ranges. The bars represent the “minimum” and “maximum” values. Outliers are shown as circles. CT chemotherapy, ET endocrine therapy, RT radiotherapy

Overall breast cancer care

Adherence to CGs for the overall breast cancer care was measured only in three studies with a range from 54 and 69% [35, 57, 58] and included patients receiving treatment from 1995 to 2012. These studies varied in what process they considered as part of overall care: one included RT, CT, ET, initial examination, and follow-up indications and found that only half of the clinicians were adherent to CGs (54%) [35]; the second study evaluated nine quality indicators for diagnosis, surgery, therapy, and follow-up, and found 64% of adherence to CGs [58]; and the third measured seven process indicators of breast cancer care including follow-up and found 69% of adherence with the 80% of cut-off, and 38% when it increased to 90% [57].

Overall treatment process

Six studies addressed the overall treatment process (surgery, CT, ET, and RT). These studies represented patients receiving treatment in the period from 1991 to 2009 [28, 32, 41, 48, 59, 63]. The median adherence was 57.5% (IQR 38.8–67.3%), and ranged from 29 [63] to 91% [32]. A subgroup analysis of the BRENDA I study [22] found that only 15% of patients with bilateral breast cancer (BBC) received a compliant treatment, requiring 100% of compliance to define adherence.

Systemic therapy

Five studies addressed systemic therapy (CT and ET indications). These studies included patients receiving treatment in the period from 1992 to 2012 [27, 50, 57, 66, 71]. The median adherence for systemic therapy was 76% (IQR 68–77%), and ranged from 53 [66] to 82% [71].

Adherence to breast cancer CGs—procedures or therapies (assessed separately)

Pre-treatment procedures

Five studies addressed the procedures before starting treatment. [35, 57, 58, 65, 73]. These procedures were initial examination [35], indicating mammography before surgery [57, 58]; using ultrasonography after mammography when applicable [65]; and assessing HER2 receptors status before surgery [73]. The median adherence for pre-treatment procedures was 86% (IQR 82–96%), and ranged from 81%, for indicating mammography [57], to 99%, for HER2 status assessment [73].

Surgical procedures

Three studies assessed compliance for more than one surgical procedure. These studies included patients receiving treatment in the period from 1992 to 2008 [20, 35, 63].The median adherence for surgical procedures was 86.3% (IQR 75.7–89.2%), and ranged from 65 [63] to 92% [35].

Moreover, eleven studies measured adherence for individual surgical procedures which included (1) breast-conserving surgery (BCS) [45, 58, 60,61,62], the median adherence was 74% (IQR 75.7–93%), and ranged from 35 [60] to 95% [45]; (2) mastectomy (MA) [25, 45, 60], the adherence ranged from 54 [60] to 91% [45]; (3) SLNB [58, 62, 72], from 51 [62] to 76% [72]; (4) ALND [58, 59, 73], from 68 [58] to 81% [59]; and (5) other indicators included organisational indicators [54] or “breast surgery without needing a second surgery” [57], which reported 17% and 97% of adherent treatment, respectively.

Chemotherapy

Fifteen studies addressed CT, including patients receiving treatment in the period between 1992 and 2016 [20, 29, 35, 39, 43, 44, 46, 50, 58,59,60,61, 63, 71, 73]. The median adherence was 88% (IQR 80–90%), and ranged from 60 [39] to 100% [58]. Additionally, one study [70] assessed compliance with CGs recommendations for the treatment of CT-induced anaemia and found that 95% of patients received erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) according to CGs.

Endocrine therapy

Twelve studies addressed recommendations for ET, including patients receiving treatment in the period between 1992 and 2016 [20, 31, 35, 39, 43, 44, 50, 58, 59, 61, 63, 73]. The median adherence was 90% (IQR 87–92.5%), and ranged from 76 [50] to 96% [73].

Targeted anti-HER2 therapy

Three studies assessed recommendations for the use of anti-HER2 therapy, including patients receiving treatment in the period between 2003 and 2009 [40, 51, 64]. The adherence values were 31% [51], 77% [64], and 94% [40].

Radiotherapy

Twelve studies addressed recommendations for RT, including patients receiving treatment in the period between 1992 and 2016 [26, 35, 36, 50, 57,58,59,60,61, 63, 71, 75]. The median adherence was 89.5% (IQR 81.5–93%), and ranged from 48 [34] to 97% [36, 73].

Supportive measures during therapies

Five studies [37, 38, 49, 54, 74] addressed procedures aimed to prevent adverse events during treatment, including patients receiving treatment in the period between 1996 and 2017. The median adherence was 75% (IQR 63–75%, and ranged from 19 [46] to 96% [37]. These recommendations included (1) using antiemetics to avoid acute or delayed emesis induced by chemotherapy [37]; (2) applying measures to prevent surgical infections [46]; (3) using primary prophylaxis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factors in patients receiving chemotherapy [27]; (4) monitoring left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) during anti-HER2 therapy [76], and (5) indicating vitamin D and calcium in patients receiving adjuvant non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors [75].

Follow-up

Six studies addressed follow-up indications, including patients receiving treatment in the period between 1995 and 2013 [35, 42, 55, 57, 58, 69]. The median adherence was 74% (IQR 10–80%), and ranged from 0 [58] to 84% [57]. One study reported that “consultations and mammograms for follow-up purposes were excessive”, and this was the reason for non-compliance [42].

Primary prevention strategies

One study [45] addressed primary prevention strategies in primary care, related to the management of women with concerns about familial breast cancer, and found that 80% of the general practitioners were compliant with CGs.

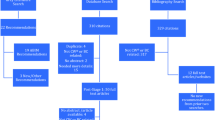

Barriers for healthcare providers’ adherence to breast cancer CGs

Sixteen studies described and analysed potential barriers for adherence to CGs, and factors associated with non-adherent indications. These barriers were categorised as internal and external factors [6]; the latter included patient-related factors and structural/organisational barriers (Table 3, Fig. 3).

Barriers for healthcare providers’ adherence to breast cancer CGs. Based on main categories proposed by Cabana et al. [6]

Internal factors, represented by healthcare provider-related factors for non-adherence to CGs, include their perceptions, preferences, knowledge, and attitudes regarding CGs recommendations. A qualitative study [56] explored the barriers for the implementation of CGs for preventive treatment for women at increased risk of breast cancer. According to providers’ perceptions, the reasons for non-adherence were the perceived lack of benefit of the interventions, being poorly informed and finding difficulties interpreting recommendations [56]. Another retrospective study reported that non-adherent indications in surgery reflected providers’ preferences for using specific techniques [45].

In other cases, these non-adherent indications would be intentional and conscious healthcare providers' decisions, as described in a case study [34] conducted within an [“optimal”] setting, where a CGs-based clinical decision support system (OncoDoc2) was routinely applied. They found that all non-compliant decisions concerned mostly a group of patients and decisions (i.e. elderly patients in pre-surgery decisions, patients with micro-invasive tumour in re-excision decisions, and patients with positive hormone receptors and HER2+ in adjuvant decisions). These discordances were found mainly in areas where scientific evidence is lacking, and the non-adherence behaviour, in this case, was actually intentional and conscious [34] (Table 3, Fig. 3).

External factors include the patient-related factors and structural factors. The patients’ age was the patient-related factor that appeared consistently associated with non-adherent treatment [20, 21, 30, 31, 33, 34, 40, 45, 48, 50, 63, 64, 68, 72]. In comparison with younger patients, older women were less likely to receive CGs concordant surgery, CT and RT, but were more likely to receive guideline-concordant ET. The intrinsic tumour characteristics were also associated with non-adherent behaviours, such as the gene expression profile [47] having triple-negative breast cancer [12, 68] or being diagnosed with higher tumour stages [20, 63]. Non-adherence was also associated with comorbidities [20, 27, 29, 32, 40, 64] [e.g. in patients with cardiovascular diseases, it was more frequent to withhold trastuzumab [40], or in patients with cognitive impairment it was more frequent the delay starting chemotherapy [29]]. Other patient-related factors included the quality of life (QoL) and low socioeconomic status (SES) [31]. Poor QoL was associated with non-adherence to ET [31]. If the QoL was good, older age was not related to deviation [30]. Low SES patients were more likely to be undertreated with CT than patients with higher SES; however, an association with ET was not found [29, 44]. Previous treatment also influenced non-adherence, e.g. RT was associated with an increased follow-up consultation [42], the absence of prior axillary surgery, with non-adherence to adjuvant decisions [33], and the type of CT received [37] with non-indicating therapies to prevent side effects.

The structural factors represent the environmental or organisational characteristics of the healthcare system were associated with non-adherent behaviour. One study reported that non-compliant decisions were mainly “choices of multidisciplinary staff meetings” [34]. Other factors associated with adherence to CGs recommendations were the academic activity in the organisation [38], geographical location [63], and the volume of departments [72] (Table 3, Fig. 3).

Discussion

Main findings

We synthesised the literature exploring the healthcare providers’ adherence to breast cancer CGs published in the last 20 years across eight European countries. Most followed a retrospective cohort design and were considered to have a low or moderate risk of bias. Adherence for overall breast cancer care process (from diagnosis to follow-up) ranged from 54 to 69%, for the overall treatment process (including surgery, CT, ET, and RT) the median adherence was 57.5% (IQR 38.8–67.3%), while for systemic therapy it was 76% (IQR 68–77%). The median adherence values for the processes assessed individually were higher, ranging from 74% (IQR 10–80%) for the follow-up to 90% (IQR 87–92.5%) for ET. Factors that potentially impact on healthcare providers’ adherence were internal: their perceptions, preferences, lack of knowledge, or intentional decisions; and external: the patient-related and structural factors. The most consistent factor for non-adherence was the age of patients.

Our results in the context of previous research

Previous systematic reviews addressing adherence of healthcare providers to CGs recommendations but out of the scope of breast cancer care [76,77,78,79], found similar results to our review, these studies reported a wide range of adherence values, depending on the specific criteria evaluated or the treatment modality. From 8.2 to 65.3%, for a set of CGs [76]; from 5 to 95% for different recommendations in the management of acute coronary syndromes [77]; and from 0.3 to 100% in antibiotic prophylaxis [78]. One study found 50% of adherence for cancer-associated thrombosis [79], lower than the median estimated for the overall treatment process in breast cancer care (58%).

Previous systematic reviews have also explored the main barriers to healthcare providers’ adherence in other healthcare areas [77, 78, 81, 82]. The factors they reported are consistent with our findings: the internal factors related to health professionals' limited skills or competences to use a therapy, and their poor knowledge, a low level of awareness, familiarity or confidence with the commonly used therapy (prior to CGs-recommended therapy), or a perceived lack of benefit of the "new" therapy [80,81,82]. They also pointed out as internal factors those related to intentional non-adherence [77]. Those highlighted as external factors include patient-related factors, such as comorbidities and patient-level barriers [78, 80], as well as structural factors, such as organisational characteristics like being a teaching hospital [78].

Other additional factors identified in previous studies included poor organisational- or institutional-level support, inadequate peer support among health professionals, the complex nature of some therapies or guidelines [80], the expectation that compliance is mandatory [4], or the patients' preferences or demands [4, 81].

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. The broad eligibility criteria we applied helped to capture the complete picture of the healthcare providers’ adherence to breast cancer CGs in Europe. We included studies with any design reporting the measure of adherence even for single CGs recommendations. The detailed data extraction process helped us to provide a synthesis of adherence proportions by treatment modality, although definitions or selected recommendations were variable. We could identify different reporting elements across definitions and methods to measure adherence. For factors associated with healthcare providers’ adherence, we adapted a conventional classification, which highlights factors to be considered by breast cancer CGs developers and other relevant stakeholders.

Our study also has some limitations. Included studies were conducted in eight European countries, with more than half of them coming from two countries (The Netherlands and Italy). Therefore, we should be cautious when interpreting results and cannot extrapolate our findings to other European countries. Since we included studies of patient cohorts from the 1990s, when the implementation of guidelines was starting, we might be underestimating CGs adherence values. We identified only one qualitative study exploring factors for non-adherence to breast cancer CGs, possibly explained by the type of databases we selected. Another important limitation is that guideline non-adherence data did not differentiate deliberate guideline deviations from unjustified practice variation. This was not possible to explore as most of the included studies did not specify the reasons for non-adherence. Other factors, like changes between versions or discrepancies between several national and international guidelines, could have potentially influenced guideline deviations. However, this analysis was not feasible.

Implications for practice and research

This systematic review summarises for first-time healthcare providers’ adherence to breast cancer guidelines in Europe. Even though observed median proportions seem to be acceptable for most specific treatments, there is still room for improvement for healthcare providers’ adherence, especially for supportive measures during therapy as well as during follow-up. Advances in breast cancer screening and treatment have reduced breast cancer mortality across the age spectrum in the past decade [73, 74]. However, we identified that the most consistent external factor associated with non-adherence to CGs was the older age of patients. Breast CGs might not adequately address this subpopulation, or they may represent a population where the evidence to develop breast cancer guidelines is scarce.

We found high variability in the methods used to measure, define, and report adherence. Future studies should provide the rationale to define adherence with enough transparency and should always consider the strength of a recommendation in their selection. In usual care, healthcare providers may not be aware of the standards required for CGs and may be tempted to select low-quality recommendations [74]. Hence, to facilitate the use of evidence supporting healthcare recommendations, guideline developers should use rigorously developed presentation formats (e.g. decisions aids, clinical decision trees). In agreement with other authors [75, 76], we believe it is necessary to provide a selection of relevant, reliable, and reproducible definitions for unwarranted clinical variation in healthcare [76], in this case for breast cancer care. Use of robust methods to measure adherence, avoiding the selection or performance bias, with appropriate blinding of assessment, will help to evaluate this process in a more reliable and reproducible way. The development of more qualitative research to capture breast cancer healthcare providers' perspective should be fostered. Furthermore, health care providers should register the reasons for non-adherence to facilitate that real-world data inform guideline updating.

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of breast cancer patients appear not to be receiving CGs-recommended care. Aligning healthcare provider’s decisions with breast cancer CGs recommendations in European countries should be improved for almost all processes of care, especially for preventive therapies and follow-up. Knowing the reasons for non-compliance is essential to understand these deviations. The development and implementation of CGs for breast cancer patients should address relevant patient-related factors to enhance the applicability of CGs in clinical care.

Data availability

The datasets used or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CGs :

-

Clinical guidelines

- RT :

-

Radiotherapy

- CT :

-

Chemotherapy

- ET :

-

Endocrine therapy or hormonal therapy

- BCS :

-

Breast-conserving surgery

- MT :

-

Mastectomy

- ALND:

-

Axillary lymph node dissection

- TNBC :

-

Triple-negative breast cancer

- SLNB :

-

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

- HER2 :

-

Human epidermal growth receptor 2

References

Institute of Medicine (US), Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines, Field MJ, Lohr KN (1992) Guidelines for clinical practice: from development to use. National Academies Press (US), Washington (DC)

Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust (2011) National Academy Press (US), Washington DC. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209546/. Accessed 31 July 2019

Gurses AP, Marsteller JA, Ozok AA, Xiao Y, Owens S, Pronovost PJ (2010) Using an interdisciplinary approach to identify factors that affect clinicians' compliance with evidence-based guidelines. Crit Care Med 38(8 Suppl):S282–S291

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A et al (2003) The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 348(26):2635–2645

Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA (2013) Committee on improving the quality of cancer care: addressing the challenges of an aging population BoHCS, institute of medicine. Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. National Academies Press (US), Washington (DC)

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA et al (1999) Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 282(15):1458–1465

van Fenema EM (2017) Assessment of guideline adherence and quality of care with routine outcome monitoring data. Tijdschr Psychiatr 59(3):159–165

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Dyba T, Randi G, Bettio M et al (2018) Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer 103:356–387

Luengo-Fernandez R, Leal J, Gray A, Sullivan R (2013) Economic burden of cancer across the European union: a population-based cost analysis. Lancet Oncol 14(12):1165–1174

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G et al (2010) AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. J Clin Epidemiol 63(12):1308–1311

Gandhi S, Verma S, Ethier JL, Simmons C, Burnett H, Alibhai SM (2015) A systematic review and quality appraisal of international guidelines for early breast cancer systemic therapy: are recommendations sensitive to different global resources? Breast 24(4):309–317

Schwentner L, Wolters R, Koretz K, Wischnewsky MB, Kreienberg R, Rottscholl R et al (2012) Triple-negative breast cancer: the impact of guideline-adherent adjuvant treatment on survival–a retrospective multi-centre cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 132(3):1073–1080

Wockel A, Kurzeder C, Geyer V, Novasphenny I, Wolters R, Wischnewsky M et al (2010) Effects of guideline adherence in primary breast cancer–a 5-year multi-center cohort study of 3976 patients. Breast 19(2):120–127

Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H (2010) Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement Sci 5:56

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535

Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS (2016) Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 6(12):e011458

National Institute of Health (2014) Study quality assessment tools USA. https://www-nhlbi-nih-gov.are.uab.cat/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed 31 July 2019

Wells GSB, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P (2013) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 31 July 2019

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme CASP Qualitative Checklist (2018). https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf. Accessed 31 July 2019

Ebner F, Hancke K, Blettner M, Schwentner L, Wockel A, Kreienberg R et al (2015) Aggressive Intrinsic Subtypes in Breast Cancer: a predictor of guideline adherence in older patients with breast cancer? Clin Breast Cancer 15(4):e189–e195

Hancke K, Denkinger MD, Konig J, Kurzeder C, Wockel A, Herr D et al (2010) Standard treatment of female patients with breast cancer decreases substantially for women aged 70 years and older: a German clinical cohort study. Ann Oncol 21(4):748–753

Schwentner L, Wolters R, Wischnewsky M, Kreienberg R, Wockel A (2012) Survival of patients with bilateral versus unilateral breast cancer and impact of guideline adherent adjuvant treatment: a multi-centre cohort study of 5292 patients. Breast 21(2):171–177

Van Ewijk R, Wockel A, Gundelach T, Hancke K, Janni W, Singer S et al (2015) Is guideline-adherent adjuvant treatment an equal alternative for patients aged %3e65 who cannot participate in adjuvant clinical breast cancer trials? A retrospective multi-center cohort study of 4,142 patients. Arch Gynecol Obstet 291(3):631–640

Varga D, Wischnewsky M, Atassi Z, Wolters R, Geyer V, Strunz K et al (2010) Does guideline-adherent therapy improve the outcome for early-onset breast cancer patients? Oncology 78(3–4):189–195

Wockel A, Varga D, Atassi Z, Kurzeder C, Wolters R, Wischnewsky M et al (2010) Impact of guideline conformity on breast cancer therapy: results of a 13-year retrospective cohort study. Onkologie 33(1–2):21–28

Wockel A, Wolters R, Wiegel T, Novopashenny I, Janni W, Kreienberg R et al (2014) The impact of adjuvant radiotherapy on the survival of primary breast cancer patients: a retrospective multicenter cohort study of 8935 subjects. Ann Oncol 25(3):628–632

Wollschlager D, Meng X, Wockel A, Janni W, Kreienberg R, Blettner M et al (2017) Comorbidity-dependent adherence to guidelines and survival in breast cancer-Is there a role for guideline adherence in comorbid breast cancer patients? A retrospective cohort study with 2137 patients. Breast J 24:120–127

Wolters R, Wischhusen J, Stuber T, Weiss CR, Krockberger M, Bartmann C et al (2015) Guidelines are advantageous, though not essential for improved survival among breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 152(2):357–366

Leinert E, Schwentner L, Blettner M, Wockel A, Felberbaum R, Flock F et al (2019) Association between cognitive impairment and guideline adherence for application of chemotherapy in older patients with breast cancer: results from the prospective multicenter BRENDA II study. Breast J 25:386–392

Schwentner L, Van Ewijk R, Kuhn T, Flock F, Felberbaum R, Blettner M et al (2016) Exploring patient- and physician-related factors preventing breast cancer patients from guideline-adherent adjuvant chemotherapy-results from the prospective multi-center study BRENDA II. Support Care Cancer 24(6):2759–2766

Stuber T, van Ewijk R, Diessner J, Kuhn T, Flock F, Felberbaum R et al (2017) Which patient- and physician-related factors are associated with guideline adherent initiation of adjuvant endocrine therapy? Results of the prospective multi-centre cohort study BRENDA II. Breast Cancer 24(2):281–287

Bouaud J, Seroussi B (2011) Revisiting the EBM decision model to formalize non-compliance with computerized CPGs: results in the management of breast cancer with OncoDoc2. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011:125–134

Seroussi B, Laouenan C, Gligorov J, Uzan S, Mentre F, Bouaud J (2013) Which breast cancer decisions remain non-compliant with guidelines despite the use of computerised decision support? Br J Cancer 109(5):1147–1156

Seroussi B, Soulet A, Messai N, Laouenan C, Mentre F, Bouaud J (2012) Patient clinical profiles associated with physician non-compliance despite the use of a guideline-based decision support system: a case study with OncoDoc2 using data mining techniques. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2012:828–837

Ray-Coquard I, Philip T, Lehmann M, Fervers B, Farsi F, Chauvin F (1997) Impact of a clinical guidelines program for breast and colon cancer in a French cancer center. JAMA 278(19):1591–1595

Wimmer T, Ortmann O, Gerken M, Klinkhammer-Schalke M, Koelbl O, Inwald EC (2019) Adherence to guidelines and benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy in patients with invasive breast cancer: results from a large population-based cohort study of a cancer registry. Arch Gynecol Obstet 299:1131–1140

Van Ryckeghem F, Haverbeke C, Wynendaele W, Jerusalem G, Somers L, Van den Broeck A et al (2019) Real-world use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in ambulatory breast cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer 27(3):1099–1108

DURTO (2013) Antiemetic prescription in Italian breast cancer patients submitted to adjuvant chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 11(12):785–789

Roila F, Ballatori E, Patoia L, Palazzo S, Veronesi A, Frassoldati A et al (2003) Adjuvant systemic therapies in women with breast cancer: an audit of clinical practice in Italy. Ann Oncol 14(6):843–848

de Munck L, Schaapveld M, Siesling S, Wesseling J, Voogd AC, Tjan-Heijnen VC et al (2011) Implementation of trastuzumab in conjunction with adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of non-metastatic breast cancer in the Netherlands. Breast Cancer Res Treat 129(1):229–233

de Roos MA, de Bock GH, Baas PC, de Munck L, Wiggers T, de Vries J (2005) Compliance with guidelines is related to better local recurrence-free survival in ductal carcinoma in situ. Br J Cancer 93(10):1122–1127

Grandjean I, Kwast AB, de Vries H, Klaase J, Schoevers WJ, Siesling S (2012) Evaluation of the adherence to follow-up care guidelines for women with breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 16(3):281–285

Heins MJ, de Jong JD, Spronk I, Ho VKY, Brink M, Korevaar JC (2017) Adherence to cancer treatment guidelines: influence of general and cancer-specific guideline characteristics. Eur J Pub Health 27(4):616–620

Kuijer A, Verloop J, Visser O, Sonke G, Jager A, van Gils CH et al (2017) The influence of socioeconomic status and ethnicity on adjuvant systemic treatment guideline adherence for early-stage breast cancer in the Netherlands. Ann Oncol 28(8):1970–1978

Schaapveld M, de Vries EG, Otter R, de Vries J, Dolsma WV, Willemse PH (2005) Guideline adherence for early breast cancer before and after introduction of the sentinel node biopsy. Br J Cancer 93(5):520–528

Schaapveld M, de Vries EG, van der Graaf WT, Otter R, Willemse PH (2004) Quality of adjuvant CMF chemotherapy for node-positive primary breast cancer: a population-based study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 130(10):581–590

Schreuder K, Kuijer A, Rutgers EJT, Smorenburg CH, van Dalen T, Siesling S (2017) Impact of gene-expression profiling in patients with early breast cancer when applied outside the guideline directed indication area. Eur J Cancer 84:270–277

van de Water W, Bastiaannet E, Dekkers OM, de Craen AJ, Westendorp RG, Voogd AC et al (2012) Adherence to treatment guidelines and survival in patients with early-stage breast cancer by age at diagnosis. Br J Surg 99(6):813–820

Visser A, van de Ven EM, Ruczynski LI, Blaisse RJ, van Halteren HK, Aben K et al (2016) Cardiac monitoring during adjuvant trastuzumab therapy: guideline adherence in clinical practice. Acta Oncol 55(4):423–429

Weggelaar I, Aben KK, Warle MC, Strobbe LJ, van Spronsen DJ (2011) Declined guideline adherence in older breast cancer patients: a population-based study in the Netherlands. Breast J 17(3):239–245

Poncet B, Colin C, Bachelot T, Jaisson-Hot I, Derain L, Magaud L et al (2009) Treatment of metastatic breast cancer: a large observational study on adherence to French prescribing guidelines and financial cost of the anti-HER2 antibody trastuzumab. Am J Clin Oncol 32(4):369–374

Aristei C, Amichetti M, Ciocca M, Nardone L, Bertoni F, Vidali C (2008) Radiotherapy in Italy after conservative treatment of early breast cancer. A survey by the Italian Society of Radiation Oncology (AIRO). Tumori 94(3):333–341

de Bock GH, Vliet Vlieland TP, Hakkeling M, Kievit J, Springer MP (1999) GPs' management of women seeking help for familial breast cancer. Fam Pract 16(5):463–467

Mylvaganam S, Conroy EJ, Williamson PR, Barnes NLP, Cutress RI, Gardiner MD et al (2018) Adherence to best practice consensus guidelines for implant-based breast reconstruction: results from the iBRA national practice questionnaire survey. Eur J Surg Oncol 44(5):708–716

Natoli C, Brocco D, Sperduti I, Nuzzo A, Tinari N, De Tursi M et al (2014) Breast cancer "tailored follow-up" in Italian oncology units: a web-based survey. PLoS ONE 9(4):e94063

Smith SG, Side L, Meisel SF, Horne R, Cuzick J, Wardle J (2016) Clinician-reported barriers to implementing breast cancer chemoprevention in the UK: a qualitative investigation. Public Health Genom 19(4):239–249

Andreano A, Rebora P, Valsecchi MG, Russo AG (2017) Adherence to guidelines and breast cancer patients survival: a population-based cohort study analyzed with a causal inference approach. Breast Cancer Res Treat 164(1):119–131

Barni S, Venturini M, Molino A, Donadio M, Rizzoli S, Maiello E et al (2011) Importance of adherence to guidelines in breast cancer clinical practice. The Italian experience (AIOM). Tumori 97(5):559–563

Jacke CO, Albert US, Kalder M (2015) The adherence paradox: guideline deviations contribute to the increased 5-year survival of breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer 15:734

Ottevanger PB, De Mulder PH, Grol RP, van Lier H, Beex LV (2004) Adherence to the guidelines of the CCCE in the treatment of node-positive breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 40(2):198–204

Sacerdote C, Bordon R, Pitarella S, Mano MP, Baldi I, Casella D et al (2013) Compliance with clinical practice guidelines for breast cancer treatment: a population-based study of quality-of-care indicators in Italy. BMC Health Serv Res 13:28

Schrodi S, Niedostatek A, Werner C, Tillack A, Schubert-Fritschle G, Engel J (2015) Is primary surgery of breast cancer patients consistent with German guidelines? Twelve-year trend of population-based clinical cancer registry data. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 24(2):242–252

Lebeau M, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Bellera C, Tunon-de-Lara C, Daban A, Lipinski F et al (2011) Breast cancer care compared with clinical Guidelines: an observational study in France. BMC Public Health 11:45

Liebrich C, Unger G, Dlugosch B, Hofmann S, Petry KU (2011) Adopting guidelines into clinical practice: implementation of trastuzumab in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer in lower Saxony, Germany, in 2007. Breast Care (Basel) 6(1):43–50

Vercauteren LD, Kessels AG, van der Weijden T, Severens JL, van Engelshoven JM, Flobbe K (2010) Association between guideline adherence and clinical outcome for patients referred for diagnostic breast imaging. Qual Saf Health Care 19(6):503–508

Bucchi L, Foca F, Ravaioli A, Vattiato R, Balducci C, Fabbri C et al (2009) Receipt of adjuvant systemic therapy among patients with high-risk breast cancer detected by mammography screening. Breast Cancer Res Treat 113(3):559–566

Ebner F, van Ewijk R, Wockel A, Hancke K, Schwentner L, Fink V et al (2015) Tumor biology in older breast cancer patients–what is the impact on survival stratified for guideline adherence? A retrospective multi-centre cohort study of 5378 patients. Breast 24(3):256–262

Schwentner L, Wockel A, Konig J, Janni W, Ebner F, Blettner M et al (2013) Adherence to treatment guidelines and survival in triple-negative breast cancer: a retrospective multi-center cohort study with 9,156 patients. BMC Cancer 13:487

Mille D, Roy T, Carrere MO, Ray I, Ferdjaoui N, Spath HM et al (2000) Economic impact of harmonizing medical practices: compliance with clinical practice guidelines in the follow-up of breast cancer in a French Comprehensive Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol 18(8):1718–1724

Ray-Coquard I, Morere JF, Scotte F, Cals L, Antoine EC (2012) Management of anemia in advanced breast and lung cancer patients in daily practice: results of a French survey. Adv Ther 29(2):124–133

Balasubramanian SP, Murrow S, Holt S, Manifold IH, Reed MW (2003) Audit of compliance to adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy guidelines in breast cancer in a cancer network. Breast 12(2):136–141

Holm-Rasmussen EV, Jensen MB, Balslev E, Kroman N, Tvedskov TF (2017) The use of sentinel lymph node biopsy in the treatment of breast ductal carcinoma in situ: a Danish population-based study. Eur J Cancer 87:1–9

Jensen MB, Laenkholm AV, Offersen BV, Christiansen P, Kroman N, Mouridsen HT et al (2018) The clinical database and implementation of treatment guidelines by the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group in 2007–2016. Acta Oncol 57(1):13–18

Boskovic L, Gasparic M, Petkovic M, Gugic D, Lovasic IB, Soldic Z et al (2017) Bone health and adherence to vitamin D and calcium therapy in early breast cancer patients on endocrine therapy with aromatase inhibitors. Breast 31:16–19

Jensen A, Mikkelsen GJ, Vestergaard M, Lynge E, Vejborg I (2005) Compliance with European guidelines for diagnostic mammography in a decentralized health-care setting. Acta Radiol 46(2):140–147

Arts DL, Voncken AG, Medlock S, Abu-Hanna A, van Weert HC (2016) Reasons for intentional guideline non-adherence: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform 89:55–62

Engel J, Damen NL, van der Wulp I, de Bruijne MC, Wagner C (2017) Adherence to cardiac practice guidelines in the management of non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a systematic literature review. Curr Cardiol Rev 13(1):3–27

Gouvea M, Novaes Cde O, Pereira DM, Iglesias AC (2015) Adherence to guidelines for surgical antibiotic prophylaxis: a review. Braz J Infect Dis 19(5):517–524

Mahe I, Chidiac J, Helfer H, Noble S (2016) Factors influencing adherence to clinical guidelines in the management of cancer-associated thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 14(11):2107–2113

Baatiema L, Otim ME, Mnatzaganian G, de-Graft Aikins A, Coombes J, Somerset S (2017) Health professionals' views on the barriers and enablers to evidence-based practice for acute stroke care: a systematic review. Implement Sci 12(1):74

Egerton T, Diamond LE, Buchbinder R, Bennell KL, Slade SC (2017) A systematic review and evidence synthesis of qualitative studies to identify primary care clinicians' barriers and enablers to the management of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 25(5):625–638

Slade SC, Kent P, Patel S, Bucknall T, Buchbinder R (2016) Barriers to primary care clinician adherence to clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Clin J Pain 32(9):800–816

Funding

The systematic review was carried out by the Iberoamerican Cochrane Center under Framework Contract 443094 for procurement of services between European Commission Joint Research Centre and Asociación Colaboración Cochrane Iberoamericana. YS is funded by China Scholarship Council (No. 201707040103). MR is funded by Sara Borrell contract (CD16/00157). AVM received a training Grant D43 TW007393 Fogarty International Centre of the US National Institutes of Health for the Emerging Diseases and Climate Change Research Unit of the School and Public Health Administration at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ENDG, YS, PAC, CC, LN, JP, MR, DR, IS, AV, and IR conducted the systematic review. IR, DR, IS, CC, PAC, and LN contributed to the definition of the research protocol. IS conducted the search strategy. IR, AV, ENDG, JP, YS, and MR conducted study selection, data extraction, and quality appraisal of included studies. ENDG and YS conducted the statistical analysis. IR, ENDG, AV, JP, YS, MR, IS, DR, CC, PAC, and LN contributed to the interpretation and reporting of the results. YS and ENDG drafted the first version of the article. All authors reviewed critically reviewed and provided comments on subsequent versions of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Zuleika Saz Parkinson, Luciana Neamtiu, and Elena Parmelli are current employees of the Joint Research Centre, European Commission; Ignacio Ricci-Cabello, Ena Niño de Guzmán, Javier Pérez-Bracchiglione, Yang Song, Montserrat Rabassa, Iván Solà, David Rigau, Carlos Canelo-Aybar, and Pablo Alonso-Coello are employees of the Iberoamerican Cochrane Center.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niño de Guzmán, E., Song, Y., Alonso-Coello, P. et al. Healthcare providers’ adherence to breast cancer guidelines in Europe: a systematic literature review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 181, 499–518 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05657-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05657-8