Abstract

Purpose

Women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) experience lingering confusion and anxiety, and may use the Internet for supplemental information. This study assessed the content and quality of DCIS information on the Internet.

Methods

We searched Google for English-language, publicly available DCIS information tools published from 2010 to current by non-profit organizations. We summarized tool characteristics, DCIS labels, and information important to women with DCIS corresponding to domains of a patient-centred care (PCC) framework. Tool quality was appraised with the DISCERN instrument.

Results

Of 39 tools included, most were plain language summaries published since 2016. Tools employed a median of 2.0 labels (range 1.0 to 5.0) for DCIS, most frequently non-invasive breast cancer (29, 74.4%), abnormal cells (14, 35.9%), pre-cancer (14, 35.9%), and early form of breast cancer (13, 33.3%). Tools addressed a median of 4.0 (range 2.0 to 5.0) PCC domains. Few tools contained content in the domains of fostering the relationship (30.8%), addressing emotions (41.0%), or follow-up (41.0%); 74.4% noted the risk of progression or recurrence but provided vague details. Tools were assessed as high (25.6%), moderate (48.7%), and low (25.6%) quality.

Conclusions

Few DCIS information tools available to women on the Internet meet quality criteria for consumer health information or address concerns of importance to women with DCIS. By identifying a range of poorly defined terms used to label DCIS, and specific content domains that were lacking, this study identified how existing tools could be improved, and identified higher-quality tools that clinicians can use when discussing DCIS with patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Patient-centred care (PCC), which addresses patient clinical needs, life circumstances, and personal preferences [1, 2], is a fundamental element of high-quality health care because it has improved multiple patient and health system outcomes across numerous settings of care [3,4,5,6]. A scoping review of 19 studies published from 1994 to 2011 identified 25 unique frameworks or models that offer insight on how to achieve PCC [7]. Common domains across those PCC frameworks are predicated on information, which facilitates patient–clinician communication, educates and empowers patients, addresses patient concerns or emotions, clarifies uncertainties about risks and outcomes, enables informed decision-making, and enhances patient self-management [8]. Various types of information tools, acquired by patients themselves or provided to patients by clinicians, support PCC. For example, educational material helps patients understand their condition [9], question prompt lists help patients communicate with clinicians [10], and decision aids help patients articulate preferences [11]. Single interventions of information tools in print or electronic format that inform or activate patients can positively impact patient knowledge, communication, decision-making, and health behaviour [12].

PCC is particularly relevant for conditions where there is limited evidence to support decision-making, two or more treatment options are suitable, or when treatment outcomes may be adverse as is sometimes the case for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). DCIS includes several abnormal cell types confined to the breast ducts with variable risk of progression and recurrence [13]. While about 20% of women with DCIS will develop invasive disease, the 20-year breast cancer-specific mortality is a favourable 3.3% [14]. The effectiveness of tests to predict progression [15], and management with active surveillance [16,17,18] are under investigation. Thus, standard care is lumpectomy or mastectomy and possible radiotherapy or hormone therapy [19, 20], Physicians have said it is difficult to describe DCIS [21, 22]. Women with DCIS told they have “stage 0 cancer” or “pre-cancer”, have inaccurate perceptions of the risk of invasive cancer, recurrence and survival, and report receiving little clarifying information or opportunity for discussion, causing confusion and anxiety well after treatment, and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [23,24,25,26]. Thus, while clinical outcomes may be favourable, the patient experience during and after treatment may be less than ideal.

Clearly, to improve PCC and HRQoL for women with DCIS, tools are needed that offer thorough and accurate information about DCIS, and distinguish it from invasive breast cancer. Increasingly, patients turn to the Internet for health information, and women use the Internet as a source of health information more than men [27]. Sharing of Internet-acquired information by patients during appointments can foster communication and improve the patient–clinician relationship [28], and supplement information provided by clinicians [29]. However, clinicians have raised concerns about the accuracy of online health information [30]. The purpose of this study was to assess the content and quality of DCIS information tools available to women on the Internet. This may identify useful resources that could be broadly employed to support PCC for DCIS, or it may reveal the need to develop or improve DCIS information tools if such resources are sparse or of poor quality.

Methods

Approach

Content analysis was employed to assess DCIS information tools identified on the Internet [31]. A manifest content analysis approach was used [32]. This refers to qualitatively and/or quantitatively describing explicit content as reported in written, verbal, or visual communication, without theoretical analysis or interpretation of its underlying meaning. Directed/deductive and summative content analysis techniques were employed to categorize information within tools according to an existing PCC framework (directed/deductive) [8], and to enumerate the number and type of information tools and their content (summative) [31, 32]. While not technically a literature synthesis, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria guided the conduct and reporting of the review [33]. Ethics review and approval was not necessary because information material was publicly available.

Eligibility

In the absence of a gold-standard definition or taxonomy of patient information tools, we defined eligible tools using the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) recommendations for reporting knowledge-based interventions (Table 1) [34].

Exclusion criteria were generated concurrent with screening. The following types of information tools were not eligible: publication date or developer not specified, requiring subscription or purchase, clinical practice guidelines, research articles or editorials, risk assessment calculators, clinical trials, insurance services, keynote speaker presentations, videos, news items, social media forums or support groups, or Wikipedia or other similar open-editing web sites. Resources developed by for-profit organizations were excluded due to inconsistency in availability and cost. While some of these excluded tools such as videos or support groups may provide women with information about DCIS, we aimed for uniformity in selecting print or electronic tools comprised of text and/or graphics so that quality could be assessed similarly using a common instrument and compared across tools.

Searching

JB searched the Internet using Google from 22 June to 27 June 2018. With no standard methods for searching “grey literature” on the Internet [35, 36], we employed the following strategy. JB conducted preliminary searches of Google using “DCIS or ductal carcinoma in situ” to develop a list of labels or titles for potential information tools until no further unique terms emerged. Then “DCIS or ductal carcinoma in situ” were successively combined with each of the unique labels for potential information tools including booklet, brochure, decision aid, fact sheet, handout, leaflet, pamphlet, patient information, communication aid, question prompt list, summary, and toolkit. JB and BN conducted a pilot test to determine how many pages of Google search results included relevant results. They executed the same four searches and perused the results to assess how many results were relevant. Both agreed that no further potentially relevant results were apparent after six pages (ten results per page). JB proceeded to search Google using all search term combinations. All search results were exported or copied into an Excel spreadsheet for screening.

Screening

JB, BN, HL, and ARG independently screened titles of the first 100 search results against eligibility criteria. JB compared independent screening to identify discrepancies, and ARG met with JB, BN, and HL to discuss the discrepancies and how to apply the screening criteria. Then JB screened all remaining titles. All potentially relevant items were retrieved for full-text screening. JB and BN independently screened 50 full-text tools on 10 July 2018. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with ARG. JB then screened remaining full-text tools.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed in Excel to collect tool attributes (title, author or developer, country, publication year, tool type, breast cancer or DCIS-specific, DCIS definition, and labels) and content. Content extracted from each tool (Table 2) corresponded to the top ten questions deemed essential from among 117 unique questions specified by women with DCIS when asked what they most wanted to know upon diagnosis [37], which we mapped to domains of the McCormack et al. PCC framework [8], chosen because it is the most comprehensive PCC framework and specific to cancer. To pilot data extraction, JB and BN independently extracted data from six tools on 22 Aug 2018 and identified discrepancies, which were discussed with ARG to achieve consensus. JB extracted data from all remaining tools.

Data analysis

Summary statistics were used to report the number and proportion of tools by type and per content extracted. The quality of all included items was assessed with DISCERN, a validated, widely used instrument to assess the quality of consumer health information, comprised of 15 items pertaining to reliability and content, plus 1 overall quality score [38]. Each item was independently assessed by JB and BN, who achieved consensus through discussion and consultation with ARG, who resolved discrepancies. TF independently confirmed scoring. As per scoring instructions, each items is scored on a 5-point scale converted to yes (5), partially (2–4) or not met (1), and overall scores were based on item scoring.

Results

Search results

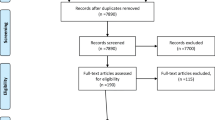

Searching resulted in 759 unique results, and 621 were excluded by title screening. Among 138 full-text tools screened, 96 were excluded based on publication type (51) or date (11), they could not be located (15), lacked any DCIS content (14), were not freely available (9) or were developed by a for-profit organization (3), leaving 39 tools eligible for review (Supplementary File 1). Extracted data are included in Supplementary File 2 [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80].

Tool characteristics

Tool attributes are summarized in Table 3. Information tools were published between 2011 and 2018; nearly two-thirds (27, 69.2%) were published more recently in the last 3 years from 2016 to 2018. Most tools were developed by organizations in the United States (18, 46.2%), followed by England (10, 25.6%), Australia (5, 12.8%), 2 (5.1%) in each of Canada and New Zealand, and 1 (2.6%) in each of Ireland and Scotland. Information tools were largely developed by charities or foundations (13, 33.3%), treatment centres/hospitals (10, 25.6%), and governments (6, 15.4%) or governmental agencies (5, 12.8%), followed by patient support services (2, 5.1%), and 1 (2.6%) each by a professional society, patient advocacy group, and partnership between a charity and an academic institution. With respect to tool type, most tools were printable plain language summaries featuring text and/or graphic information (25, 64.1%, range 1 to 107 pages) that were labelled by developers as booklets, brochures, fact sheets, FAQs, handouts, leaflets, or pamphlets. Remaining tools were web sites (12, 30.8%) comprised of single or multiple pages, and 2 (5.1%) were printable decision aids. Most tools were specific to DCIS (25, 64.1%) while 14 (35.9%) pertained to breast cancer and included information about DCIS.

DCIS labels

Tools employed a median of 2.0 labels (range 1.0 to 5.0) for DCIS (Supplementary File 3). The most frequently used term was non-invasive breast cancer (29, 74.4%). Approximately one-third of tools employed the terms abnormal cells (14, 35.9%), pre-cancer or pre-invasive cancer (14, 35.9%), and early form of breast cancer (13, 33.3%). Fewer tools used the labels stage 0 cancer (9, 23.1%) or cancer cells (6, 15.4%). Only 2 (5.1%) tools solely used the term ductal carcinoma in situ, and only 1 (2.4%) tool specified that it was not breast cancer.

PCC domains

No tools addressed all six PCC domains [7] corresponding to questions of importance to women with DCIS [37] (Supplementary File 4). Tools addressed a median of 4.0 PCC domains (range 2.0 to 5.0). A total of 10 (25.6%), 10 (25.6%), 17 (43.6%), and 2 (5.1%) tools addressed 5, 4, 3, and 2 PCC domains, respectively. Findings did not appear to differ by publication year, country, or developer.

Fostering the relationship

Fostering the relationship was the least-addressed domain. A total of 12 (30.8%) tools named specialties involved in DCIS care. For example: “Surgical, medical and radiation oncologists work together with pathologists, plastic and reconstructive surgeons, nurses, genetics counselors and pharmacists to develop an individualized treatment plan…” Ten (25.6%) tools also specified the role of each specialty. For example: “The pathologist writes a pathology report that says whether you have DCIS or not”. and “A radiation oncologist is a doctor who gives breast cancer patients special X-rays to kill their cancer cells”.

Exchanging information

Most tools addressed “exchanging information” by defining or describing DCIS. A total of 37 (94.9%) specified that DCIS was distinct from invasive breast cancer because it was contained within the milk ducts. For example: “DCIS is a non-invasive type of breast cancer that occurs when abnormal cells are found solely within the milk ducts”. A total of 12 (30.8%) also described different grades of DCIS. For example: “With ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) the three grades are usually called low, intermediate and high instead of 1, 2 or 3”. Four (10.3%) tools also included questions that patients could ask of clinicians.

Addressing emotions

Resources inconsistently “addressed emotions” by acknowledging or validating feelings of concern or anxiety (16, 41.0%) or offering coping strategies (7, 17.9%), and this content was often brief or vague. For example, “Finding out you have breast cancer can leave you feeling a range of emotions. Fear, shock, sadness and anger are all common feelings at this time. Remember that there are people who can support you so do not be afraid to ask for help”. [72]

Managing uncertainty

Many tools addressed “managing uncertainty” by noting the risk of progression or recurrence (29, 74.4%). However, most provided brief and vague information; for example: “DCIS has a very good prognosis (outlook)” [39] or “Risk of invasive cancer or DCIS recurrence is very low”. [60] Only 8 (20.5%) tools offered statistics to describe risks; for example, “Most recurrences happen within 5–10 years of initial diagnosis. The chances of recurrence are under 30%” [51] or “Women who have had DCIS are 4–12 times more likely to develop subsequent invasive breast cancer despite treatment”. [75]

Making decisions

All 39 tools addressed “making decisions” by describing treatment options including different means of diagnosis, surgical approaches, adjuvant treatments, and options for reconstruction following mastectomy. Of those, 26 (66.7%) tools also rationalized the need for treatment despite DCIS being non-invasive. For example: “DCIS may, if left untreated, develop the ability to spread outside of the ducts, known as invasive cancer”. [48]

Enabling self-management

Enabling self-management was inconsistently addressed by included tools by describing what to expect after treatment. Few tools described follow-up care (16, 41.0%) and most of those provided little detail; for example, “Now that you have been diagnosed with DCIS, it is very important that you have regular breast exams”. [76] A greater number of tools (24, 61.5%) offered self-care advice with respect to lifestyle factors and/or provided contact information or links for sources of additional information or support.

Quality assessment

With respect to quality, 10 (25.6%), 19 (48.7%), and 10 (25.6%) tools were assessed with the DISCERN instrument [38] as high, moderate, and low quality, respectively (Supplementary File 5). High quality was not associated with year of publication, country, or developer type; however, 6 of 10 (60.0%) high-quality tools addressed 5 of 6 PCC domains.

Discussion

This study identified 42 DCIS information tools available to women on the Internet. Most were printable plain language summaries published since 2016 that referred to DCIS using a wide variety of labels. Many tools failed to address PCC domains that correspond to questions of importance to women with DCIS [8, 37], and few tools were assessed as high quality [38]. Overall, these findings underscore the need to develop or improve DCIS information tools that could help clinicians communicate with women diagnosed with DCIS, and supplement clinician discussions to reduce confusion and inaccurate perceptions among women.

Other research highlights increasing use of the Internet as a source of breast cancer information, and the poor quality of that information. For example, analysis of Google data revealed increasing use of the Internet for cancer information, and that breast cancer was the top search [78]. Self-report questionnaire data from 27,491 breast cancer patients between 2007 and 2013 also showed increasing use of the Internet as a source of information, particularly among those younger than 70 years of age, with 10 or more years of formal education, and lower cancer stage [79]. Assessment of 30 English- and 30 German-language web sites on side effects of radiotherapy for breast cancer with DISCERN found that most were poor quality [80]. While Lo et al. [37] identified questions important to women with DCIS, we found no prior published studies that developed or evaluated DCIS information tools. Similarly, in a scoping review of 51 studies published from 1997 to 2016, we identified only two that developed or evaluated educational interventions targeted to either patients or clinicians to support patient awareness, knowledge, discussions, or decision-making about DCIS [81]. Thus, our findings are unique in their focus on DCIS, and in the context of related research demonstrating increasing use of the Internet as a source of information by breast cancer patients, emphasizes the importance of developing or improving DCIS information tools on the Internet.

Our research identifies specific ways to develop, or improve the content and quality of DCIS information tools. We found that DCIS information tools used a wide variety of terms, most commonly, non-invasive breast cancer, abnormal cells, pre-cancer or pre-invasive cancer, or early form of breast cancer; thus, one option is to consistently employ and define terms for DCIS. It is well-recognized that use of medicalized terms by clinicians prompts higher anxiety ratings and perceived disease severity among patients with various conditions, and preference for more aggressive management [82, 83]. This is also true of women with DCIS, who preferred use of terminology without the cancer label to describe DCIS [84, 85]. While some experts have advocated for changes to terminology for lesions with low malignant potential [86], other experts argue that use of non-cancer labels may be deceptive and limit informed decision-making [87]. Using a two-round Delphi of 27 women with DCIS and 29 clinicians, we generated Canadian consensus recommendations on PCC for DCIS, which included a recommendation to refine DCIS nomenclature [88], In future research, we plan to engage international experts including DCIS survivors, clinicians, cancer staging and classification agencies, cancer societies, and breast cancer trials groups and advocacy groups in identifying the potential benefits and harms of various DCIS labels.

A second option for improving the content and quality of DCIS information tools is to more thoroughly address PCC domains, which correspond to questions of importance to women with DCIS [8, 37]. Doing so may help clinicians discuss DCIS with patients, engage patients in their own care, and improve the care experience and HRQoL in women newly diagnosed with DCIS and DCIS survivors. In particular, our study found that few tools contained content relevant to the domains of fostering the relationship, addressing emotions, managing uncertainty, or enabling self-management, demonstrating the need for DCIS tools to include more information on the role of various specialties involved in DCIS care; acknowledging and validating feelings of concern or anxiety, and offering coping strategies; providing specific details about the risk of progression to invasive breast cancer and of recurrence; and describing follow-up care processes and self-care advice. Once developed, research is needed to evaluate the impact of such tools on patient–clinician communication and patient outcomes such as perceived PCC and HRQoL.

With respect to clinical practice, these findings could help clinicians to direct women with DCIS to useful online tools since patients who conduct their own searches may not find all resources that were assessed as high quality or appraise the resources they find to ascertain those that might be more useful. Also, clinicians could benefit from reviewing the resources assessed as high quality to help them in discussion DCIS with their patients.

Strengths of this study include use of rigorous and unique methods to identify and screen tools, and extract and summarize data; compliance with research reporting standards [33]; use of an established PCC framework [8], which corresponds to the concerns of women with DCIS [37], upon which to map DCIS information tool content; and use of a validated instrument to assess DCIS information tool quality [38]. Several factors may limit the interpretation and application of the findings. Despite employing a thorough search strategy, we may not have identified all relevant DCIS information tools, particularly because we restricted our search to English-language tools and resources developed only by non-profit organizations. Furthermore, we did not include for-profit Internet resources that may be available to and used by women.

In conclusion, despite increasing use of the Internet as a source of information by women with breast cancer or DCIS, only 25.0% of DCIS information tools available to women on the Internet meet quality criteria for consumer health information or address concerns of importance to women with DCIS. By identifying a range of poorly defined terms used to label DCIS, and specific content domains that were lacking, this study revealed how existing tools could be improved, and important considerations for the future development of tools, and identified resources that clinicians can use when discussing DCIS with patients.

References

Institute of Medicine (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press, Washington DC

Carman KL, Workman TA (2017) Engaging patients and consumers in research evidence: applying the conceptual model of patient and family engagement. Patient Educ Couns 100:25–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.009

Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA (2013) Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 70(4):351–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558712465774

Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D (2013) A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570

Stewart M, Ryan BL, Bodea C (2011) Is patient-centred care associated with lower diagnostic costs? Healthc Policy 6(4):27–31

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (2015) Patient- and family-centered care initiatives in acute care settings: a review of the clinical evidence, safety and guidelines. Ontario, Ottawa

Constand MK, MacDermid JC, Dal Bello-Haas V, Law M (2014) Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare BMC Health Serv Res 14:271. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-271

McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D et al (2011) Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med 72(7):1085–1095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.020

Fonhus MS, Dalsbo TK, Johansen M, Fretheim A, Skirbekk H, Flottorp SA (2018) Patient-mediated interventions to improve professional practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD012472, https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012472.pub2

Alegria M, Carson N, Flores M, Li X, Shi P, Lessios AS, Polo A, Allen M, Fierro M, Interian A, Jimenez A, La Roche M, Lee C, Lewis-Fernandez R, Livas-Stein G, Safar L, Schuman C, Storey J, Shrout PE (2014) Activation, self-management, engagement, and retention in behavioral health care. JAMA Psychiatry 71:557–565. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4519

Scalia P, Durand MA, Berkowitz JL, Ramesh NP, Faber MJ, Kremer JAM, Elwyn G (2018) The impact and utility of encounter patient decision aids: systematic review, meta-analysis and narrative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.12

Gagliardi AR, Legare F, Brouwers MC, Webster F, Badley E, Straus S (2016) Patient-mediated knowledge translation interventions for clinical encounters: a systematic review. Implement Sci 11:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0389-3

Partridge AH, Elmore JG, Saslow D et al (2012) Challenges in ductal carcinoma in situ risk communication and decision-making. CA Cancer J Clin 62:203–210. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21140

Narod SA, Iqbal J, Giannakeas V et al (2015) Breast cancer mortality after a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ. JAMA Oncol 1:888–896. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2510

Raldow AC, Sher D, Chen AB et al (2016) Cost effectiveness of the Oncotype DX score for guiding treatment of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol 34:3963–3968. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.67.8532

Francis A, Thomas J, Fallowfeld L et al (2015) Addressing overtreatment of screen detected DCIS; the LORIS trial. Eur J Cancer 51:2296–2303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.017

Elshof LE, Tryfonidis K, Slaets L et al (2015) Feasibility of a prospective, randomised, open-label, international multicentre, phase III, non-inferiority trial to assess the safety of active surveillance for low risk ductal carcinoma in situ–the LORD study. Eur J Cancer 51:1497–1510

Hwang ES, Hyslop T, Lynch T et al (2019) The COMET (comparison of operative versus monitoring and endocrine therapy) trial: a phase III randomized controlled trial for low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). BMJ Open 9(3):e026797. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026797

Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Balassanian R et al (2018) Breast cancer, version 4.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 16(3):310–320. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2018.0012

Virnig BA, Tuttle TM, Shamliyan T et al (2010) Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: a systematic review of incidence, treatment and outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:170–178. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djp482

Kennedy F, Harcourt D, Rumsey N (2009) Perceptions of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) among UK health professionals. Breast 18:89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2009.01.004

Partridge A, Winer JP, Golshan M et al (2008) Perceptions and management approaches of physicians who care for women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin Breast Cancer 8:275–280. https://doi.org/10.3816/CBC.2008.n.032

Ruddy KJ, Meyer ME, Giobbie-Hurder A et al (2013) Long-term risk perceptions of women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Oncologist 18:362–368. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0376

Prinjha S, Evans J, Ziebland S et al (2011) A mastectomy for something that wasn’t even truly invasive cancer’. Women’s understanding of having a mastectomy for screen-detected DCIS: a qualitative study. J Med Screen 18:34–40

Davey C, White V, Warne C et al (2011) Understanding a ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosis: patient views and surgeon descriptions. Eur J Cancer Care 20:776–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01265.x

Lauzier S, Maunsell E, Levesque P et al (2010) Psychocological distress and physical health in the year after diagnosis of DCIS or invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 120:685–691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-009-0477-z

Bidmon S, Terlutter R (2015) Gender differences in searching for health information on the Internet and the virtual patient-physician relationship in Germany: exploratory results on how men and women differ and why. J Med Internet Res 17:e156. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4127

Tan SS, Goonawardene N (2017) Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 19:e9

Haase KR, Thomas R, Gifford W, Holtslander L (2018) Perspectives of healthcare professionals on patient Internet use during the cancer experience. Eur J Cancer Care 30:e12953. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12953

Wang J, Ashvetiya T, Quaye E et al (2018) Online health searches and their perceived effect on patients and patient-clinician relationships: a systematic review. Am J Med 131:e1250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.04.019

Elo S, Kyngäs H (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 62:107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15:1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Albrecht L, Archibald M, Arseneau D, Scott SD (2013) Development of a checklist to assess the quality of reporting of knowledge translation interventions using the workgroup for intervention development and evaluation research (WIDER) recommendations. Implement Sci 8:52

Benzies KM, Premji S, Hayden KA et al (2006) State-of-the-evidence reviews: advantages and challenges of including grey literature. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 3:55–61

Adams J, Hillier-Brown FC, Moore HJ et al (2016) Searching and synthesising ‘grey literature’ and ‘grey information’ in public health: critical reflections on three case studies. Syst Rev 5:164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0337-y

Lo AC, Olson R, Feldman-Stewart D, Truong PT, Aquino-Parsons C, Bottorff J, Carolan H (2017) A patient-centered approach to evaluate the information needs of women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Clin Oncol 40:574–581. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0000000000000184

Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R (1999) DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health 53:105–111

Breast Cancer Care (2018) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (BCC39). Breast Cancer Care, London. https://www.breastcancercare.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/pdf/bcc39_dcis_2018_web.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

Cancer Council Western Australia (2018) Understanding breast cancer—a guide for people with cancer, their families and friends. Cancer Council Western Australia, Subiaco, Western AU. https://www.cancerwa.asn.au/resources/2018-07-28-understanding-breast-cancer.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation (2018) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation, Encino, CAhttps://www.drsusanloveresearch.org/ductal-carcinoma-situ-dcis. Accessed 18 July 2018

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2018) Breast cancer noninvasive. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Plymouth Meeting, PA. https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/stage_0_breast/files/assets/common/downloads/files/stage0breast.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

National Health Service—Scotland (2018) Informing women about the benefits and risks of breast screening. National Health Service—Scotland , Edinburgh, SCT. http://www.portobello-conandoylesurgery.co.uk/Priority%201%20-%20benefits%20and%20risk%20of%20breast%20screening.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

Nova Scotia Health Authority—Nova Scotia Cancer Care Program (2018) Information for Patients receiving radiation therapy: breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast. Nova Scotia Health Authority—Nova Scotia Cancer Care Program, Halifax, NS. http://www.nshealth.ca/sites/nshealth.ca/files/patientinformation/nsccp1242.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

Komen SG (2018) Facts for life: ductal carcinoma in situ. Dallas, TX. https://ww5.komen.org/uploadedFiles/_Komen/Content/About_Breast_Cancer/Tools_and_Resources/Fact_Sheets_and_Breast_Self_Awareness_Cards/DuctalCarcinomaInSitu.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

Komen SG (2018) Treatment for DCIS. Denver, CO. https://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/RecommendedTreatmentsforDuctalCarcinomaInSitu.html. Accessed 09 July 2018

Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center—Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (2018) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast. Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center—Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute, Columbus, OH. https://patienteducation.osumc.edu/Documents/dcis.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust (2018) Enhanced recovery after breast surgery: an information guide. Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust, Manchester. http://www.pat.nhs.uk/downloads/patient-information-leaflets/breast-surgery/771%20Enhanced%20recovery%20after%20breast%20surgery.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

University of Iowa: Hospitals and Clinics (2018) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). University of Iowa: Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA. https://uihc.org/health-topics/ductal-carcinoma-situ-dcis. Accessed 18 July 2018

American Society of Clinical Oncology (2017) ASCO answers: breast cancer. American Society of Clinical Oncology, Alexandria, VA. https://www.cancer.net/sites/cancer.net/files/asco_answers_breast.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

BreastCancer.org (2017) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). BreastCancer.org, Ardmore, PA. https://www.breastcancer.org/symptoms/types/dcis. Accessed 09 July 2018

BreastScreen Aotearoa (2017) Breast conditions: ductal carcinoma in situ. BreastScreen Aotearoa, Palmerston North, NZ. https://www.healthed.govt.nz/system/files/resource-files/HE1812_BSA%20factsheet_Ductal%20carcinoma%20in%20situ.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

Cancer Australia—Australian Government (2017) Ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Australia—Australian Government, New South Wales, AU. https://breast-cancer.canceraustralia.gov.au/types/ductal-carcinoma-situ. Accessed 18 Jul 2018

Cancer Research UK (2017) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Cancer Research UK, London. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/breast-cancer/stages-types-grades/types/ductal-carcinoma-insitu-dcis. Accessed 18 Jul 2018

Cancer Treatment Centers of America (2017) Ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Boca Raton, FL. https://www.cancercenter.com/breast-cancer/types/tab/ductal-carcinoma-insitu/. Accessed 18 Jul 2018

Healthtalk.org—DIPEx—University of Oxford (2017) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Healthtalk.org—DIPEx—University of Oxford, Oxford.http://www.healthtalk.org/peoples-experiences/cancer/ductal-carcinoma-situ-dcis/what-ductal-carcinoma-situ-dcis. Accessed 18 July 2018

National Health Service (2017) NHS breast screening—helping you decide. National Health Service, England. http://www.uhs.nhs.uk/Media/SUHTInternet/Services/BreastImagingUnit/NHS-Breast-Screening—helping-you-decide.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

Alaska Breast Care and Surgery (2016) DCIS—ductal carcinoma in-situ. Alaska Breast Care and Surgery, Anchorage, AKhttp://www.alaskabreastcare.com/DCIS.html. Accessed 09 July 2018

American Cancer Society (2016) Treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GAhttps://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/treatment/treatment-of-breast-cancer-by-stage/treatment-of-ductal-carcinoma-insitu-dcis.html. Accessed 09 July 2018

California Department of Health Care Services (2016) A woman’s guide to breast cancer treatment. California Department of Health Care Services, Sacramento, CA (2016) http://www.mbc.ca.gov/Publications/Brochures/breast_cancer_english.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

Living Beyond Breast Cancer (2016) Guide for the newly diagnosed. Living Beyond Breast Cancer, Bala Cynwydhttps://www.lbbc.org/sites/default/files/GuideForTheNewlyDiagnosed_2016.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

National Health Service (2016) Breast cancer in women. National Health Service, Londonhttps://www.nhs.uk/conditions/breast-cancer/. Accessed 09 July 2018

Bright-Thomas R, Worcester Breast Surgery (2016) Patient leaflet–ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Worcester Breast Surgery, Worcestershire. http://www.worcesterbreastsurgery.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/DCIS.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals—NHS Foundation Trust (2016) Ductal carcinoma-in situ treatment completion. Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals—NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle. http://www.newcastle-hospitals.org.uk/services/20619.aspx. Accessed 09 July 2018

Contiga V (2016) Know about ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and treatment. Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation, Toronto, ON. https://www.uhn.ca/PatientsFamilies/Health_Information/Health_Topics/Documents/Know_about_DCIS_and_treatment.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

American Cancer Society (2015) Special section: breast carcinoma in situ. American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2015/special-section-breast-carcinoma-insitu-cancer-facts-and-figures-2015.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

Macmillan Cancer Support (2015) A practical guide to understanding cancer—understanding ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Macmillan Cancer Support, London. http://be.macmillan.org.uk/Downloads/CancerInformation/CancerTypes/MAC12870DCISe30150501.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

Westmead Breast Cancer Institute (2015) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Westmead Breast Cancer Institute, New South Wales, AU. https://www.bci.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/BCI_DCIS_8DL_2015_WEB.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

Breast Cancer Action (2014) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Breast Cancer Action, San Francisco, CA. https://bcaction.org/site-content/uploads/2010/11/DCIS-factsheet1.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

Breast Cancer Now (2013) The best treatment Your guide to breast cancer treatment in England and Wales. Breast Cancer Now, London. https://breastcancernow.org/sites/default/files/public/best_treatment_guide_-_england_and_wales.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

Cancer Australia—Australian Government (2013) Breast cancer fact sheet. Cancer Australia—Australian Government. New South Wales, AU. https://canceraustralia.gov.au/system/tdf/publications/breast-cancer-fact-sheet/pdf/bckf_breast_cancer_factsheet_51e6410714794.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=3597. Accessed 09 July 2018

Irish Cancer Society (2013) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Irish Cancer Society, Dublin, IE. http://edepositireland.ie/bitstream/handle/2262/71949/ductal_carcinoma_in_situ.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 18 July 2018

National Cancer Institute (2012) About this booklet. National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD. https://pubs.cancer.gov/pdf/Insides-wyntk-breast.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

National Cancer Institute (2012) Surgery choices for women with DCIS or breast cancer. National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD. https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/surgery-choices/surgerychoices.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

myVMC—Virtual Medical Centre (2012) Breast cancer: pre-invasive ductal carcinoma (ductal carcinoma in situ; DCIS). myVMC—Virtual Medical Centre, Subiaco, Western AU. https://www.myvmc.com/diseases/pre-invasive-ductal-carcinoma-ductal-carcinoma-insitu-dcis-breast-cancer/. Accessed 18 July 2018

Cancer Prevention & Treatment Fund (2011) DCIS: what you need to know. Cancer Prevention & Treatment Fund, Washington DC. http://dev.stopcancerfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/DCIS-Booklet-for-Web-Site-2011-copyright-v2.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2018

Cancer society of New Zealand (2011) Ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer society of New Zealand, Wellington, NZ. https://cancernz.org.nz/assets/Uploads/IS-DuctalCarcinomaIS-3FEB2012.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2018

Foroughi F, Lam AK, Lim MSC, Saremi N, Ahmadvand A (2016) “Googling” for cancer: an infodemiological assessment of online search interests in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. JMIR Cancer 2:e5. https://doi.org/10.2196/cancer.5212

Kowalski C, Kahana E, Kuhr K, Ansmann L, Pfaff H (2014) Changes over time in the utilization of disease-related internet information in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients 2007 to 2013. JMIR 16:e195. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3289

Janssen S, Kasmann L, Fahlbusch FB, Rades D, Vordermark D (2018) Side effects of radiotherapy in breast cancer patients: the internet as an information source. Strahlenther Onkol 194:136–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-017-1197-7

Kim C, Liang L, Wright FC, Hong NJL, Groot G, Helyer L, Meiers P, Quan ML, Urquhart R, Warburton R, Gagliardi AR (2017) Interventions are needed to support patient-provider decision-making for DCIS: a scoping review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 168:579–592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4613-x

Nickel B, Barratt A, Copp T, Moynihan R, McCaffery K (2017) Words do matter: a systematic review on how different terminology for the same condition influences management preferences. BMJ Open 7:e014129. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014129

Dixon PR, Tomlinson G, Pasternak JD, Mete O, Bell CM, Sawka AM, Goldstein DP, Urbach DR (2019) The role of disease label in patient perceptions and treatment decisions in the setting of low-risk malignant potential. JAMA Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0054

Nickel B, Barratt A, Hersch J, Moynihan R, Irwig L, McCaffery K (2015) How different terminology for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) impacts women’s concern and management preferences: a qualitative study. Breast 24:673–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2015.08.004

McCaffery K, Nickel B, Moynihan R, Hersch J, Teixeira-Pinto A, Irwig L, Barratt A (2015) How different terminology for ductal carcinoma in situ impacts women’s concern and treatment preferences: a randomised comparison within a national community survey. BMJ Open 5:e008094. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008094

Esserman LJ, Thompson IM Jr, Reid B (2013) Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: an opportunity for improvement. JAMA 310:797–798. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.108415

Kohn EC, Malik S (2019) Disease labels and clear communication with patients—a rose by any other name would smell as sweet. JAMA Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0053

Gagliardi AR, Wright FC, Hong NJL, Groot G, Helyer L, Meiers P, Quan ML, Urquhart R, Warburton R (2019) National consensus recommendations on patient-centered care for ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res Treat 174:561–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05132-z

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Bryanna Nyhof, Helen Liu, and Tali Filler who helped with data collection and analysis.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (grant number 250).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Jayden Blackwood declares that he has no conflicts of interest. Frances Wright declares that she has no conflicts of interest. Nicole Look Hong declares that she has no conflicts of interest. Anna Gagliardi declares that she has no conflicts of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was not required as there were no human participants involved in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Blackwood, J., Wright, F.C., Hong, N.J.L. et al. Quality of DCIS information on the internet: a content analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 177, 295–305 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05315-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05315-8