Abstract

Background

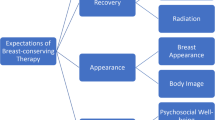

Many women eligible for breast conservation therapy (BCT) elect unilateral mastectomy (UM) with or without contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) and cite a desire for “peace of mind.” This study aimed to characterize how peace of mind is defined and measured and how it relates to surgical choice.

Methods

Nine databases were searched for relevant articles through 8 October 2023, and data were extracted from articles meeting the inclusion criteria.

Results

The inclusion criteria were met by 20 studies. Most were prospective cohort studies (65%, 13/20). In the majority of the studies (72%, 13/18), Non-Hispanic white/Caucasian women comprised 80 % or more of the study’s sample. Almost half of the studies used the phrase “peace of mind” in their publication (45%, 9/20), and few directly defined the construct (15%, 3/20). Instead, words representing an absence of peace of mind were common, specifically, “anxiety” (85%, 17/20), “fear” (75%, 15/20), and “concern” (75%, 15/20). Most of the studies (90%, 18/20) measured peace of mind indirectly using questionnaires validated for anxiety, fear, worry, distress, or concern, which were administered at multiple postoperative time points (55%, 11/20). Most of the studies (95%, 18/19) reported at least one statistically significant result showing no difference in peace of mind between BCT, UM, and/or CPM at their latest time of assessment.

Conclusion

Peace of mind is largely framed around concepts that suggest its absence, namely, anxiety, fear, and concern. Existing literature suggests that peace of mind does not differ among average-risk women undergoing BCT, UM, or CPM. Shared surgical decisions should emphasize at least comparable emotional and/or psychosocial well-being between CPM and breast conservation.

Adapted from Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj. N71. For more information, visit http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Agarwal S, et al. Effect of breast conservation therapy vs mastectomy on disease-specific survival for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:267–74.

Chen K, et al. Comparative effectiveness study of breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy in the general population: a NCDB analysis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:40127–40.

Chu QD, et al. Outcomes of breast-conserving surgery plus radiation vs mastectomy for all subtypes of early-stage breast cancer: analysis of more than 200,000 women. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;234:450–64.

Hartmann-Johnsen OJ, et al. Survival is better after breast conserving therapy than mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer: a registry-based follow-up study of Norwegian women primary operated between 1998 and 2008. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3836–45.

Hartmann-Johnsen OJ, et al. Better survival after breast-conserving therapy compared to mastectomy when axillary node status is positive in early-stage breast cancer: a registry-based follow-up study of 6387 Norwegian women participating in screening, primarily operated between 1998 and 2009. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15:118.

Kummerow KL, et al. Nationwide trends in mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(1):9–16.

Jagsi R, et al. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy decisions in a population-based sample of patients with early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:274–82.

Rosenberg SM, et al. Perceptions, knowledge, and satisfaction with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among young women with breast cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:373–81.

Tuttle TM, et al. Increasing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer patients: a trend toward more aggressive surgical treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5203–9.

Wong SM, et al. Growing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy despite no improvement in long-term survival for invasive breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2017;265:581–9.

Shiraishi M, et al. Long-term patient satisfaction and quality of life following breast reconstruction using the BREAST-Q: a prospective cohort study. Front Oncol. 2022;12:815498.

Stolpner I, et al. Long-term patient satisfaction and quality of life after breast-conserving therapy: a prospective study using the BREAST-Q. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:8742–51.

Montgomery LL, et al. Issues of regret in women with contralateral prophylactic mastectomies. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:546–52.

Anderson C, et al. Long-term satisfaction and body image after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:1499–506.

Aerts L, et al. Sexual functioning in women after mastectomy versus breast-conserving therapy for early-stage breast cancer: a prospective controlled study. Breast. 2014;23:629–36.

Andrzejczak E, Markocka-Mączka K, Lewandowski A. Partner relationships after mastectomy in women not offered breast reconstruction. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1653–7.

Pesce C, et al. Patient-reported outcomes among women with unilateral breast cancer undergoing breast conservation versus single or double mastectomy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;185:359–69.

Sando IC, et al. An evaluation of the choice for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and patient concerns about recurrence in a reconstructed cohort. Ann Plast Surg. 2018;80:333–8.

Bloom DL, et al. Reframing the conversation about contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: preparing women for postsurgical realities. Psychooncology. 2019;28:394–400.

Rosenberg SM, et al. “I don’t want to take chances”: a qualitative exploration of surgical decision-making in young breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2018;27:1524–9.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906.

Tricco AC, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

McGowan J, et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Haddaway NR, Grainger MJ, Gray CT. Citationchaser: a tool for transparent and efficient forward and backward citation chasing in systematic searching. Res Synth Methods. 2022;13:533–45.

Lodder L, et al. Psychological impact of receiving a BRCA1/BRCA2 test result. Am J Med Genet. 2001;98:15–24.

Morgan J, et al. Psychosocial outcomes after varying risk management strategies in women at increased familial breast cancer risk: a mixed-methods study of patient and partner outcomes. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2024;106:78–91.

van Oostrom I, et al. Long-term psychological impact of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation and prophylactic surgery: a 5-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3867–74.

Boughey JC, et al. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) consensus statement from the American society of breast surgeons: data on CPM outcomes and risks. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3100–5.

Daly MB, et al. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:77–102.

Lee YC, Lin YC, Huang CL, Fredrickson BL. The construct and measurement of peace of mind. J Happiness Stud. 2013;14:571–90.

Klassen AF, et al. Development and psychometric validation of BREAST-Q scales measuring cancer worry, fatigue, and impact on work. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:7410–20.

Yale university harvey cushing/john hay whitney medical, L., Reference deduplicator. 2021.

McLaughlin S, et al. Peace of mind after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: does it really happen? Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;1:S28.

Buchanan PJ, et al. An analysis of the decisions made for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:29–40.

Lim DW, et al. Longitudinal study of psychosocial outcomes following surgery in women with unilateral nonhereditary breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:5985–98.

Moyer A, Salovey P. Patient participation in treatment decision-making and the psychological consequences of breast cancer surgery. Womens Health. 1998;4:103–16.

Nissen MJ, et al. Quality of life after breast carcinoma surgery: a comparison of three surgical procedures. Cancer. 2001;91:1238–46.

Parker PA, et al. Short-term and long-term psychosocial adjustment and quality of life in women undergoing different surgical procedures for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3078–89.

Pozo C, et al. Effects of mastectomy versus lumpectomy on emotional adjustment to breast cancer: a prospective study of the first year postsurgery. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1292–8.

Retrouvey H, et al. psychosocial functioning in women with early breast cancer treated with breast surgery with or without immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:2444–51.

Wellisch DK, et al. Psychosocial outcomes of breast cancer therapies: lumpectomy versus mastectomy. Psychosomatics. 1989;30:365–73.

Arora NK, et al. Impact of surgery and chemotherapy on the quality of life of younger women with breast carcinoma: a prospective study. Cancer. 2001;92:1288–98.

Brewster AM, et al. PCORI final research reports, in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and breast cancer: clinical and psychosocial outcomes. 2018, Patient-centered outcomes research institute (PCORI).

Levy SM, et al. Mastectomy versus breast conservation surgery: mental-health effects at long-term follow-up. Health Psychol. 1992;11:349–54.

Lizarraga IM, et al. Surgical decision-making surrounding contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: comparison of treatment goals, preferences, and psychosocial outcomes from a multicenter survey of breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:8752–65.

Momoh AO, et al. Tradeoffs associated with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women choosing breast reconstruction: results of a prospective multicenter cohort. Ann Surg. 2017;266:158–64.

Parker PA, et al. Prospective study of psychosocial outcomes of having contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among women with nonhereditary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2630–8.

Portschy PR, et al. Perceptions of contralateral breast cancer risk: a prospective, longitudinal study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3846–52.

Cohen L, et al. The effects of type of surgery and time on psychological adjustment in women after breast cancer treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:427–34.

Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605.

Spitzer RL, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70.

Veit CT, Ware JE Jr. The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:730–42.

Cella D, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3-s11.

McNair DM. Profile of mood states. Educational and industrial testing service, 1992.

Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (self-evaluation questionnaire). No title, 1970.

Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The impact of event scale–revised. In: JP Wilson, TM Keane, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. The Guilford Press, 1997. p. 399–411

Schain W, et al. Psychosocial and physical outcomes of primary breast cancer therapy: mastectomy vs excisional biopsy and irradiation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1983;3:377–82.

Rakovitch E, et al. A comparison of risk perception and psychological morbidity in women with ductal carcinoma in situ and early invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;77:285–93.

Lerman C, et al. Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening. Health Psychol. 1991;10:259–67.

Vickberg SM. The concerns about recurrence scale (CARS): a systematic measure of women’s fears about the possibility of breast cancer recurrence. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25:16–24.

Simard S, Savard J. Fear of cancer recurrence inventory: development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:241–51.

Cella DF, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–9.

Fisher B, et al. Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing total mastectomy and segmental mastectomy with or without radiation in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:665–73.

Calvert M, et al. Maximising the impact of patient-reported outcome assessment for patients and society. BMJ. 2019;364:k5267.

Stamm T, et al. Building a value-based care infrastructure in Europe: the health outcomes observatory. Catalyst Non-Issue Content. 2021; 2.

Grimmer L, et al. Variation in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy rates according to racial groups in young women with breast cancer, 1998 to 2011: a report from the national cancer data base. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:187–96.

Jerome D, Emilia B, Trinh H. Socioeconomic factors associated with the receipt of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with breast cancer. J Womens Health Larchmt. 2020;29:220–9.

Jahagirdar D, et al. Using patient-reported outcome measures in health services: a qualitative study on including people with low literacy skills and learning disabilities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:431.

Lavallee DC, et al. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Aff Millwood. 2016;35:575–82.

Pugh SL, et al. Characteristics of participation in patient-reported outcomes and electronic data capture components of NRG oncology clinical trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108:950–9.

Sisodia RC, Rodriguez JA, Sequist TD. Digital disparities: lessons learned from a patient-reported outcomes program during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28:2265–8.

Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:254–8.

Cruz Rivera S, et al. The need for ethical guidance for the use of patient-reported outcomes in research and clinical practice. Nat Med. 2021;27:572–3.

Slade AL, et al. Systematic review of the use of translated patient-reported outcome measures in cancer trials. Trials. 2021;22:306.

Mouslim MC, Johnson RM, Dean LT. Healthcare system distrust and the breast cancer continuum of care. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;180:33–44.

Stan D, Loprinzi CL, Ruddy KJ. Breast cancer survivorship issues. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(805–27):ix.

Hoerger M, et al. Cognitive determinants of affective forecasting errors. Judgm Decis Mak. 2010;5:365–73.

Wilson TD, Gilbert DT. The impact bias is alive and well. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;105:740–8.

Hoerger M. Coping strategies and immune neglect in affective forecasting: direct evidence and key moderators. Judgm Decis Mak. 2012;7:86–96.

Kahneman D, et al. Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science. 2006;312:1908–10.

Acosta J, et al. Investigating the bias in orthopaedic patient-reported outcome measures by mode of administration: a meta-analysis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2020;4:e2000194.

Cabitza F, Dui LG. Collecting patient-reported outcomes in the wild: opportunities and challenges. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2018;247:36–40.

Cabitza F, Dui LG, Banfi G. PROs in the wild: assessing the validity of patient-reported outcomes in an electronic registry. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2019;181:104837.

Hammarstedt JE, et al. Survey mode influence on patient-reported outcome scores in orthopaedic surgery: telephone results may be positively biased. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:50–4.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Shoshana Rosenberg received funding from Conquer Cancer Foundation/Pfizer Global Medical Grants (NIH R01CA256877-01A1). Dr. Rachel Greenup was supported by NCI R01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

There are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamid, S.A., Bakkila, B., Schultz, K.S. et al. “Peace of Mind” After Mastectomy: A Scoping Review. Ann Surg Oncol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-024-15360-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-024-15360-3