Abstract

Background

Male breast cancer (MBC) is a rare disease for which no randomised controlled trials (RCT) have been conducted to determine optimal surgical management. The available data have been reviewed to identify reasonable options and reveal areas in need of investigation.

Methods

All published series on the surgical management of MBC have been reviewed to determine approaches to treatment of the primary, the breast and the axilla together with the psychological sequelae of surgery.

Findings

Mastectomy is still the major surgical offer but a convincing case can be made for the use of neoadjuvant endocrine treatment in order to facilitate breast conserving surgery. Sentinel node biopsy has been successfully used for staging MBC although nomograms for prediction of nodal status are inadequately calibrated. There are psychological sequelae of mastectomy in males and as yet no evidence that the needs of those with MBC are being met.

Conclusions

Collaborative studies are required so that men can participate in meaningful RCTs to provide an evidence-based rational foundation for the surgery of MBC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Men with breast cancer are a disadvantaged minority. They have been diagnosed with a disease which some considered to be an all-female affliction. This lack of awareness partly explains why more than 40% present with advanced or metastatic disease [1]. The biology of male breast cancer (MBC) differs significantly from that of female breast cancer (FBC) [2,3,4,5]. Despite this, at present, most treatment decisions are based on an extrapolation from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in FBC. Mastectomy has been the standard surgical offer for MBC whereas breast conserving therapy is widely used for selected females with the disease and has been shown to be effective in the long-term [6,7,8]. For men with breast cancer, combined approaches and thoughtful surgery are needed to achieve maximal likelihood of cure together with a minimum of long-term psychological distress.

Neoadjuvant treatment

It is extraordinary that for patients with almost invariably oestrogen receptor positive disease, often presenting with large tumours, no prospective studies of endocrine neoadjuvant therapy for MBC have been reported. Indeed, there are only a few reports of neoadjuvant chemotherapy given on an ad hoc basis [9, 10]. A potentially very useful approach has not been exploited since neoadjuvant endocrine therapy could enable some men with breast cancer to undergo a wide excision of the cancer without a need for a mastectomy or allow less extensive surgery with primary skin closure.

What form should that neoadjuvant endocrine treatment take? It has been suggested that MBC resembles post-menopausal FBC [11]. Tamoxifen has been the standard treatment for pre-menopausal women with ER+ ve breast cancer but RCTS have shown that for post-menopausal women with ER+ ve cancers, aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are superior in an adjuvant role [12]. MBC has been likened to post-menopausal FBC and so it was understandable that AIs should have also been used as adjuvant treatment for MBC [13]. Relatively small studies appeared to show a benefit from adjuvant anastrozole and letrozole [14, 15]. Subsequent larger studies were less encouraging. Harlan et al analysed outcomes in 512 MBC cases derived from the surveillance, epidemiology and end-results (SEER) database [16]. Of these, 124 (28%) received adjuvant hormonal therapy (tamoxifen 95, AI 19, tamoxifen+ AI 8, other 2). Although there was a significant reduction in cancer mortality among those given tamoxifen (HR 0.04, CI 0.1, 0.99) compared with no systemic therapy, adjuvant AIs did not reduce deaths (HR 1.2, 95% CI 0.4, 3.8).

Eggermann et al studied 257 MBC patients with ER+ ve disease reported to German cancer registries and compared their outcome with 2785 FBC cases all of whom received endocrine therapy [17]. The median follow-up of was 106 months for females and 42 months for males. Cases were matched for age, tumour stage, tumour grade, nodal status, HER2 status and receipt of chemotherapy in a 2:1 F/M ratio. The female and male patients were matched 2:1. Tamoxifen was given to 316 women and 158 men and AIs to 60 and 30 respectively. TAM-treated patients of both genders had similar 5-year OS but FBC patients treated with AIs had significantly better 5-year OS (85.0%) compared with AI-treated MBC cases 85% versus 73.3% (p = 028). The probable explanation is that testicular production of oestrogen (approximately 20%) is not abolished by AIs [18]. This indicates that tamoxifen should be the neoadjuvant endocrine therapy of choice in MBC.

Unfortunately there can be a problem with patient compliance in men taking tamoxifen. Annelli et al investigated the side effects of adjuvant tamoxifen treatment in 24 MBC cases of whom 15 (63%) complained of one or more side effect [19]. Of these, 19 had ER− ve primary tumours and the men were treated from 1990 to 1993. These included reduced libido (7) weight gain (6), hot flushes (5) and altered mood (5). One developed deep vein thrombosis. In toto, 5 (21%) stopped taking tamoxifen within 1 year compared with a female discontinuation rate of 10% [20]. Similar findings were reported by the Ottawa Hospital Cancer Centre between with 50% suffering side effects and 24% stopping the treatment in one case because of a pulmonary embolism [15]. Failure to take adjuvant therapy can lead to serious consequences. Xu et al reported a cohort of 116 MBC patients with ER+ ve disease [21]. After 1 year only 65% were still taking tamoxifen, 46% after 2 years, 29% at 3 years, 26% at 4 years and only 18% in the final year. The 10-year disease-free survival of the compliant patients was 96% compared with 42% in the non-compliers. If used as neoadjuvant treatment for shorter durations compliance might be less of a problem.

Other potential approaches include the use of GnRH analogues such as goserelin which reversibly achieve a testicular ablation but such treatment may not be acceptable to many men with MBC. The historical treatment for advanced or metastatic MBC was surgical orchidectomy but this was rejected by more than 50% of patients [22]. Balancing efficacy and toxicity will need international cooperation to run randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of neoadjuvant endocrine therapy for MBC. Collaboration has already started but until appropriately powered studies have been conducted, including quality of life metrics, treatment will continue to be given on an empirical basis without an evidence base [23,24,25].

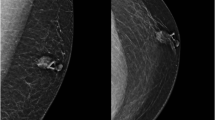

Breast conserving surgery versus mastectomy

Unlike the situation in female breast cancer, there are no RCTs to confirm the safety of breast conserving surgery for selected cases of MBC [26,27,28]. Such evidence as there is derives from historical comparisons which have the disadvantage of the associated unknown selection biases. In a series of 257 Danish MBC cases treated between 1943 and 1972, 78% had operable disease but only 15 (8%) had local excision [29]. Guinee et al reported a cohort of 308 MBC cases with operable disease of whom 30 (10%) underwent breast conserving surgery [30]. Of 229 Canadian cases, 168 were treated by mastectomy and 8 (3.5%) had a local excision and axillary clearance [31]. In the large French cohort of 489 cases only 42 (8.6%) had breast conserving surgery [32].

The surveillance, epidemiology and end-results (SEER) database has been extensively interrogated with regard to MBC. Cloyd et al reported that of 5425 males treated between 1983 and 2009, 4707 (87%) underwent mastectomy and 718 (13%) had lumpectomy, increasing from 11% between 1983 and 1986 to 15% in 2007–2009 [33]. Ten-year breast cancer-specific survival was 83% after lumpectomy and 77% following mastectomy.

In a stage-specific analysis of 4276 cases diagnosed between 1973 and 2008 Fields et al reported breast conserving surgery was used in only 10% [34]. There was similar cancer-specific survival in men treated by lumpectomy and radiotherapy compared with mastectomy (hazard ratio 1.33; 95% CI 0.49–3.61; P = 0.57). Leone et al investigated the relationship between clinico-pathological variables, locoregional treatment and overall survival (OS) in 1283 men with T1a,b,c,N0, M0 disease registered with SEER between 1988 and 2012 [35]. The sub-stages were: T1a 7%, T1b 21% and T1c 72% and within each of these mastectomy was performed in > 74%. There was no significant difference in OS for those treated by breast conservation or mastectomy. Risk factors for worse survival were older age, higher grade tumours, no surgery, no axillary staging and being unmarried.

Zaenger et al examined outcomes for 1777 males with T1/2, N0 disease, treated between 1998 and 2011 [36]. Most were treated by radical or simple mastectomy, with or without post-operative radiotherapy. Only 296 (17%) had breast conserving surgery with 135 (46%) receiving post-operative radiotherapy. The actuarial 5-year cancer-specific survival was 100% for the BCT group and 97% for MRM, for stage 1 and 91.2% for stage 2. This needs to be interpreted with caution because of the relatively short duration of follow-up.

In a study of 42 MBC cases treated in Massachusetts between 1990 and 2003, 30 underwent modified radical mastectomy (MRM), 4 simple mastectomy (SM) and 8 had breast conserving surgery (BCS) [37]. A multidisciplinary group assessed musculoskeletal function including arm oedema and range of shoulder movement. Table 1 shows that there was reduced morbidity after BCS with no lymphoedema or limitation of shoulder movement.

Psychological sequelae

Unsurprisingly there are relatively limited data concerning the psychological consequences of the diagnosis and treatment of MBC. Anxiety/depression, body image, cancer-specific distress and coping capacity were determined by Brain et al using a cross-sectional questionnaire on 161 MBC cases [38]. Clinically treatable levels of anxiety and depression were present in 6% and 1% respectively which is substantially lower than that reported in FBC [39]. Nevertheless, high levels of cancer-specific distress were reported by 23%. Within the US 2009 Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey there were 66 MBC cases and Andrykowski compared them with 198 age-matched cancer-free control males [40]. The MBC cases had a significantly increased risk of obesity, comorbidity, reduced activity, poorer life satisfaction and worse general health.

Kowalski et al examined health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in 84 male breast cancer patients and compared HRQoL scores with FBC and male non-MBC populations. In relation to FBC patients, men with MBC had higher scores in 7/8 subscales physical functioning, role functioning-physical and emotional, bodily pain, vitality, social functioning and mental health. In contrast, when compared with the general male population, MBC patients showed major defects in emotional and physical role functioning. Gaitanidis et al examined the SEER database from years 1973–2013 to determine the rate of suicide and risk factors in breast cancer patients. Of 474,128 patients 773 (0.16%) had killed themselves. The significant risk factors were age < 30 years, male sex and single status, particularly in the first year after diagnosis.

Sentinel node biopsy

There have been several series reporting ≥ 30 sentinel node biopsies for MBC, all from the USA which have been summarised in Table 2 [41,42,43,44,45,46]. The lowest identification rate (90%) occurred in the series in which not all cases received both isosulfan blue and technetium-99m [35]. This suggests that whenever possible a joint identification approach should be used.

Vaysse et al examined whether predictive factors for axillary nodal status derived from FBC were applicable to MBC [47]. They used 2 nomograms: Institut Curie (IC) [48] and Memorial Sloan-Kettering (MSKCC) [49]. The calibration and discrimination performance of both nomograms were tested in 80 men with operable cancer. Axillary lymph node involvement was present in 37 (46%). The area under the curve (AUC) of IC and MSKCC was 0.66 and 0.64 respectively, indicating inadequate calibration of both. This could have been the result of a relatively small sample size or possibly different biological determinants in the 2 genders.

Reconstruction

Until recently, reconstruction with skin flaps has used solely to achieve skin closure after mastectomy for MBC but no large series have been reported. Chastel et al used Limberg flaps for two males following modified radical mastectomy with a satisfactory result [50]. It has been argued by Spear and Bowen that a transverse rectus abdominis (TRAM) flap not only replaces the skin and fat but also provides hair-bearing cover similar to the normal male breast skin [51]. Others have also the robustness of TRAM flaps even after local relapse of MBC [52, 53]. Another approach in a debilitated patient needing a mastectomy with a chest wall defect is the delto-pectoral flap (DP) flap [54].

The latissimus dorsi (LD) flap is the reconstruction workhorse in females undergoing mastectomy and reconstruction and this technique has been used successfully in males with large and borderline operable breast cancer [55, 56]. One disadvantage is that LD flaps reduce shoulder function. This long-term morbidity may have to be accepted if local control of the cancer is to be achieved.

A variety of oncoplastic techniques have evolved to achieve a better and more symmetrical outcome after breast conserving surgery. These may be applicable for men who have both MBC and gynaecomastia, so that the cancer can be excised with a better cosmetic outcome and the contralateral breast made symmetric by reduction mammoplasty [57].

Ductal carcinoma in situ

Men have only partly escaped the epidemic of DCIS which manifests as microcalcification and represents 20% of the cancers picked up by screening. As was the case before the introduction of mammographic screening some are symptomatic. When MBC and FBC were compared using a SEER database, DCIS comprised 280/2984 (9.4%) of male cases and 53,928/454,405 (11.9%) of FBC [58]. In a series of 84 pure DCIS male cases in the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology specimen archive the median age at diagnosis was 65 years [59]. Most presented with a lump (58%) and bloody nipple manifested in 35%. In three histological studies the papillary subtype was the commonest, followed by mixed papillary and cribriform [48, 49, 60]. No pure DCIS specimens were high grade disease, with 57% low and 43% of intermediate grade.

Surgical decisions as in so many aspects of MBC have been made on an ad hoc basis. As an example, in a SEER series of 512 MBC cases there were 58 with DCIS [16]. Of these, 38 (66%) were treated by mastectomy, and one also was given post-operative radiation. Nipple-conserving surgery was performed in 18 cases of whom 7 received breast irradiation. Two cases had no surgery and the majority, 70%, had no axillary surgery. When the axilla was explored 8 had a full dissection and 9 had sentinel node biopsy. Six cases received adjuvant tamoxifen but no data were available concerning outcome. In the twenty-first century men with DCIS should have at most a sentinel node biopsy and be spared an automatic axillary clearance.

Conclusions

The rarity of MBC is the reason why, whenever possible, all cases enter collaborative studies which will include the opportunity to participate in meaningful RCTs. As a model of successful clinical research collaboration the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG) has conducted landmark RCTs in a country with only 5½ million inhabitants [61]. In countries with National Health services such as the United Kingdom, networks based around hubs of expertise could be set up. In the UK, with 350 new cases of MBC every year, 3 hubs would each oversee > 100 cases annually. Patients would not need to travel to the hub. Cases would be discussed by a central multidisciplinary meeting together with a senior clinician from referring hospital using telephone conferencing. Those men agreeing to participate would be able to enter National/International RCTs.

Information needs of new cases could be met by an outreach services provided by appropriately trained Breast Care Nurses with support from selected MBC patients, in their homes or at the local hospital. A major step towards reassuring worried patients would be the knowledge that they were being cared for by experienced professionals. The hub team would ensure central registration of all MBC together with central histopathological review to collect a minimum data set so that epidemiological studies could be rendered more effective.

References

Fentiman IS, Fourquet A, Hortobagyi GN (2006) Male breast cancer. Lancet 367:595–604

Shaaban AM, Ball GR, Brannan RA et al (2012) A comparative biomarker study of 514 matched cases of male and female breast cancer reveals gender-specific biological differences. Breast Cancer Res Treat 133:949–958

Orr N, Cooke R, Jones M et al (2011) Genetic variants at chromosomes 2q35, 5p12, 6q25.1, 10q26.13, and 16q12.1 influence the risk of breast cancer in men. PLoS Genet 9:e1002290

Johansson I, Nilsson C, Berglund P et al (2011) High-resolution genomic profiling of male breast cancer reveals differences hidden behind the similarities with female breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 129:747–760

Piscuoglio S, Murray M, Ng CKY et al (2014) The genomic landscape of male breast cancer. SABCS 22:S6–S06

Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J et al (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomised trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347:1233–1241

Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L et al (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomised study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347:1227–1232

Litière S, Werutsky G, Fentiman IS et al (2012) Breast conserving therapy versus mastectomy for stage I–II breast cancer: 20 year follow-up of the EORTC 10801 phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 13:412–419

Giordano SH, Perkins GH, Broglio C, Garcia SG, Middleton LP et al (2005) Adjuvant systemic therapy for male breast carcinoma. Cancer 104:2359–2364

Saha D, Tannenbaum S, Zhu Q (2017) Treatment of male breast cancer by dual human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) blockade and response prediction using novel optical tomography imaging: a case report. Cureus 9(7):e1481. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.1481

Anderson WF, Jatoi I, Tse J, Rosenberg PS (2009) Male breast cancer: a population-based comparison with female breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 28:232–239

Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, Buzdar A, Howell A et al (2010) Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 11:1135–1141

Anderson WF, Althuis MD, Brinton LA, Devesa SS (2004) Is male breast cancer similar or different than female breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat 83(1):77–86

Giordano SH, Perkins GH, Broglio K, Garcia SG, Middleton LP et al (2005) Adjuvant systemic therapy for male breast carcinoma. Cancer 104:2359–2364

Visram H. Kanji F, Dent SF (2010) Endocrine therapy for male breast cancer: rates of toxicity and adherence. Curr Oncol 17:17–21

Harlan LC, Zujewski JA,. Goodman MT, Stevens JL (2010) Breast cancer in men in the US: a population-based study of diagnosis, treatment and survival. Cancer 116:3558–3568

Eggemann H, Altmann U, Costa SD, Ignatov AJ (2017) Survival benefit of tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitor in male and female breast cancer. Cancer Res Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-017-2539-7

Doyen J, Italiano A, Largillier R, Ferrero JM, Fontana X, Thyss A (2010) Aromatase inhibition in male breast cancer patients: biological and clinical implications. Ann Oncol 21:1243–1245

Anelli TFM, Anelli A, Tran KN, Lebwohl DE, Borgen PI (1994) Tamoxifen administration is associated with a high rate of treatment-limiting symptoms in male breast cancer patients. Cancer 74:74–77

Love RR, Cameron L, Connell BL, Leventhal H (1991) Symptoms associated with tamoxifen treatment in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 151:1842–1847

Xu S, Yang Y, Tao W, Song Y, Chen Y et al (2012) Tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in 116 men with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 136:495–502

Bezwoda WR, Hesdorffer C, Dansey R, De Moor N, Derman DP et al (1987) Breast cancer in men. Clinical features, hormone receptor status, and response to therapy. Cancer 60:1337–1340

Di Lauro L, Pizzuti L, Barba M, Sergi D, Sperduti I et al (2015) Role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues in metastatic male breast cancer: results from a pooled analysis. J Hematol Oncol 8:53–58

Cardoso F, Bartlett JMS, Slaets L, van Deurzen CH4, van Leeuwen-Stok E et al (2017) Characterization of male breast cancer: results of the EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG International Male Breast Cancer Program. Ann Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx651

Humphries MP, Sundara Rajan S, Honarpisheh H, Cserni G, Dent J et al (2017) Characterisation of male breast cancer: a descriptive biomarker study from a large patient series. Sci Rep 7:45293. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45293

Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M et al (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347:1233–1241

Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M. Saccozzi R et al (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347:1227–1232

Litière S, Werutsky G, Fentiman IS, Rutgers E, Christiaens MR et al (2012) Breast conserving therapy versus mastectomy for stage I–II breast cancer: 20 year follow-up of the EORTC 10801 phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 13:412–419

Scheike O (1973) Male breast cancer 5. Clinical manifestations in 257 cases in Denmark. Br J Cancer 28:552–561

Guinee VF, Olsson H, Moller T, Shallenberger RC, van den Blink JW et al (1993) The prognosis of breast cancer in males. A report of 335 cases. Cancer 71:154–161

Goss PE, Reid C, Pintilie M, Lim R, Miller N (1999) Male breast carcinoma: a review of 229 patients who presented to the Princess Margaret Hospital during 40 years: 1955–1996. Cancer 85:629–639

Cutuli B, Le-Nir CC, Serin D, Kirova Y, Gaci Z et al (2010) Male breast cancer. Evolution of treatment and prognostic factors. Analysis of 489 cases. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 73:246–254

Cloyd JM, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wapnir IL (2013) Outcomes of partial mastectomy in male breast cancer patients: analysis of SEER, 1983–2009. Ann Surg Oncol 20:1545–1550

Fields EC, DeWitt P, Fisher CM, Rabinovitch R (2013) Management of male breast cancer in the United States: a surveillance, epidemiology and end results analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 87:747–752

Leone JP, Leone J, Zwenger AO et al (2017) Locoregional treatment and overall survival of men with T1a,b,cN0M0 breast cancer: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer 71:7–14

Zaenger D, Rabatic BM, Dasher B, Mourad WF (2016) Is breast conserving therapy a safe modality for early-stage male breast cancer? Clin Breast Cancer 16:101–104

Fogh S, Kachnic LA, Goldberg SI, Taghian AG, Powell SN, Hirsch AE (2013) Localized therapy for male breast cancer: functional advantages with comparable outcomes using breast conservation. Clin Breast Cancer 13:344–349

Brain K, Williams B, Iredale R, France L, Gray J (2006) Psychological distress in men with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:95–101

Ania Syrowatka A, Motulsky A, Kurteva S, Hanley JA, Dixon WG et al (2017) Predictors of distress in female breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 165:229–245

Andrykowski MA (2012) Physical and mental health status and health behaviors in male breast cancer survivors: a national, population-based, case-control study. Psycho Oncol 21:927–934

Boughey JC, Bedrosian I, Meric-Bernstam F, Ross MI, Kuerer HM et al (2006) Comparative analysis of sentinel lymph node operation in male and female breast cancer patients. J Am Coll Surg 203:475–480

Rusby JE, Smith BL, Dominguez FJ, Golshan M (2006) Sentinel lymph node biopsy in men with breast cancer: a report of 31 consecutive procedures and review of the literature. Clin Breast Cancer 7:406–410

Gentilini O, Chagas E, Zurrida S, Intra M, De Cicco C et al (2007) Sentinel lymph node biopsy in male patients with early breast cancer. Oncologist 12:512–515

Kiluk JV, Lee MC, Park CK, Meade T, Minton S et al (2011) Male breast cancer: management and follow-up recommendations. Breast J 17:503–509

Flynn LW, Park J, Patil SM, Cody HS III, Port ER (2008) Sentinel lymph node biopsy is successful and accurate in male breast carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 206:616–621

Maráz R, Boross G, Pap-Szekeres J, Markó L, Rajtár M et al (2014) The role of sentinel node biopsy in male breast cancer. Breast Cancer 23:85–91

Vaysse C, Sroussi J, Mallon P, Feron JG, Rivain AL et al (2013) Prediction of axillary lymph node status in male breast carcinoma. Ann Oncol 24:370–376

Reyal F, Rouzier R, Depont-Hazelzet B, Bollet MA, Pierga JY et al (2011) The molecular subtype classification is a determinant of sentinel node positivity in early breast carcinoma. PLoS ONE 6(5):e20297. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020297

Bevilacqua JL, Kattan MW, Fey JV et al (2007) Doctor, what are my chances of having a positive sentinel node? A validated nomogram for risk estimation. J Clin Oncol 25:3670–3679

Michel P, Chastel C, Verhelst G, Van Eukem P, Paquet JL et al (1984) Importance of the Limberg triple flap in the surgical treatment of cancer of the breast in the male. Acta Chir Belg 84:138–143

Spear SL, Bowen DG (1998) Breast reconstruction in a male with a transverse rectus abdominis flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 102:1615–1617

Cagliá P, Veroux PF, Cardillo P, Nicosia A, Mio F, Amodeo C (1998) Carcinoma of the male breast: reconstructive technique. G Chir 19:358–362

Igun GO (2000) Rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap in reconstruction for advanced male breast cancer: case report. Cent Afr J Med 46:130–132

Nakao A, Saito S, Naomoto Y, Matsuoka J, Tanaka N (2002) Deltopectoral flap for reconstruction of male breast after radical mastectomy for cancer in a patient on hemodialysis. Anticancer Res 22:2477–1479

Yamamura J, Masuda N, Kodama Y, Yasojima H, Mizutani M et al (2012) Male breast cancer originating in an accessory mammary gland in the axilla: a case report. Case Rep Med 2012:286210. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/286210

Banys-Paluchowski M, Burandt E, Banys J et al (2016) Male papillary breast cancer treated by wide resection and latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction: a case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Oncol 7:420–424

Brenner P, Berger A, Schneider W, Axmann HD (1992) Male reduction mammoplasty in serious gynecomastias. Aesthet Plast Surg 16:325–330

Anderson WF, Devesa SS (2005) In situ male breast carcinoma in the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database of the National Cancer Institute. Cancer 104:1733–1741

Hittmair AP, Lininger RA, Tavassoli FA (1998) Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) in the male breast: a morphologic study of 84 cases of pure DCIS and 30 cases of DCIS associated with invasive carcinoma—a preliminary report. Cancer 83:2139–2149

Cutuli B, Dilhuydy JM, De Lafontan B, Berlie J, Lacroze M et al (1997) Ductal carcinoma in situ of the male breast. Analysis of 31 cases. Eur J Cancer 33:35–38

Jensen MB, Ejlertsen B, Mouridsen HT, Christiansen P, Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (2016) Improvements in breast cancer survival between 1995 and 2012 in Denmark: the importance of earlier diagnosis and adjuvant treatment. Acta Oncol 55(Suppl 2):24–35

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain and studies with human participants performed by the author.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fentiman, I.S. Surgical options for male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 172, 539–544 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4952-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4952-2