Abstract

This paper defends global realism about the units of selection, the view that there is always (or nearly always) an objective fact of the matter concerning the level at which natural selection acts. The argument proceeds in two stages. First, it is argued that global conventionalist-pluralism is false. This is established by identifying plausible sufficient conditions for irreducible selection at a particular level, and showing that these conditions are sometimes satisfied in nature. Second, it is argued that local pluralism – the view that while realism is true of some selection regimes, pluralist conventionalism holds for others – should also be rejected. I show that the main arguments for local pluralism are consistent with global realism. I also suggest that local pluralism offers an unacceptably disunified view of the metaphysics of selection. It follows that we should accept global realism. But this leaves open the question of how to classify so called ‘multi-level selection type 1’ (MLS1) processes, such as Wilson’s classic trait-group model for the evolution of altruism: should they be interpreted as particle selection or collective selection? On the assumption of global realism, at most one of these is correct. I argue, against global realists such as Sober, that MLS1 processes should be understood as particle, not collective, selection, due to three features of MLS1: the reducibility of collective fitness, the absence of collective reproduction, and the dispensable role of collectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This paper addresses the issue of realism vs. pluralism/conventionalism about the units of selection, which is (as Sober notes 2011, 162) one of the most important, yet unresolved, philosophical questions about the nature of selection. There are different forms of pluralism: some, such as ‘unit pluralism’, which accepts that as a matter of objective fact selection operates at multiple levels, are compatible with realism. Others, such as ‘model pluralism’, which holds that particular selective episodes can be legitimately modelled in terms of different units or agents of selection, and there is no fact of the matter concerning the level at which selection is acting, are anti-realist, or conventionalist views. My focus in this paper is on conventionalist pluralism, and that is what I shall mean by ‘pluralism’. By ‘realism’ I shall mean the view that for the selective episode in question, there is an objective fact of the matter concerning the level(s) at which selection is acting.

The issue of realism vs. pluralism has generally been understood in terms of the debate between global realism – the view that there is always a fact of the matter about the level at which selection is acting, the entities being selected, etc. – and global pluralism – the view that there is never a fact of the matter about these things (e.g. Sober 2011).Footnote 1 One need not be a global realist or pluralist however. Local pluralism is the view that for some selective episodes there is not a fact of the matter about the level at which selection is acting, such that pluralism is permissible with regard to these episodes (Okasha 2006; Boucher 2020). Thus we have the following four views:

-

1.

Global realism: there is always a fact of the matter concerning the level(s) at which natural selection acts.

-

2.

Global pluralism: there is never a fact of the matter concerning the level(s) at which natural selection acts.

-

3.

Local realism: for some selective episodes, there is a fact of the matter concerning the level(s) at which natural selection acts.

-

4.

Local pluralism: for some selective episodes, there is not a fact of the matter concerning the level(s) at which natural selection acts.

Global realism comes in different forms. If global realism is correct, there is always a determinate fact of the matter concerning the entities (or combination of entities) subject to selection in any given case, but this leaves open the question of which entities are being selected. Darwin held that it is always (or nearly always) the organism; Dawkins (circa 1976) held that it is always the gene; multi-level selectionists (e.g. Gould 2002, Sober and Wilson 1998) hold that selection acts at multiple levels. In particular (and this is my focus in this paper), within the global realist camp, there is disagreement over the right way to understand what is going on in what is known as multi-level selection type 1 (MLS1) cases. In ‘collective selection’ (I employ scare quotes as whether this is really collective selection is something we will consider) of the MLS1 variety the focus is on changes in the prevalence of types of particles in the metapopulation over time, with collectives acting as a context or environment affecting the fitnesses of particles.Footnote 2 ‘Collective’ selection of this type leads to the evolution of properties of particles (such as altruism), not collectives, and while it is collectives (as well as particles) that are the bearers of fitness (of a kind), it is the particles that reproduce and pass on their traits. The fitness of a collective in MLS1 (fitness1) is defined as the number of particles it contributes to the next generation, or the average fitness of the particles composing the collective. In multi-level selection type 2 (MLS2), the focus is rather on changes in the prevalence of types of collectives over time. Collectives, as well as particles, reproduce, and pass on their traits to offspring collectives, i.e. there is collective heritability. In MLS2 collective fitness (fitness2) is defined in terms of number of offspring collectives, and can vary independently of the fitness of the particles that compose the collectives, and of the fitness1 of the collectives (on the difference between MLS1 and MLS2 see e.g. Okasha 2006, Arnold and Fristrup 1982, Sober 1984, Damuth and Heisler 1988; see Jeler 2020 for a recent discussion). Take two collectives, X and Y, containing equal numbers of particles. X may contribute more particles to the next generation than Y, but Y may contribute more collectives to the next generation. In that case X would have the higher fitness1, but Y would have the higher fitness2 (Okasha 2006, loc. 729).Footnote 3

If one is a global realist, one could regard MLS1 cases as (really) instances of higher-level selection, or one could regard them as (really) instances of lower-level selection. But at most one of these can be correct.Footnote 4

I will thus be concerned with four positions: global pluralism; global realism with MLS1 cases interpreted as higher-level selection; global realism with MLS1 cases interpreted as lower-level selection; and local pluralism (in particular, the combination of pluralism about MLS1 cases, and realism about MLS2 cases).Footnote 5 In this paper I defend the third position - global realism with MLS1 cases interpreted as lower-level selection.

Summary of the argument (in three premises).

Premise one

Sufficient conditions for selection acting at a level are sometimes satisfied in nature. Thus global pluralism is false.

Premise two

The main arguments for local pluralism do not establish it, as they are consistent with global realism. And local pluralism seems to be metaphysically incoherent, or at least unstable, suggesting we ought to accept either global realism or global pluralism. Given we have rejected the former (P1), we ought to accept global realism.

Given P1, i.e. given we’re accepting realism about some selective episodes, what P2 says is in effect that we have no reason to stop there, no reason not to extend this to all selective episodes. The arguments for preserving anti-realist pluralism about certain episodes are not persuasive. Given global realism is the simpler, more unified view, we ought to adopt it.

P1 states that global pluralism is false, and P2 states that we should reject local pluralism. If follows from P1 and P2 that we should accept global realism. But which form of it? If global realism is correct, MLS1 is either objectively collective selection or objectively particle selection.

Premise three

MLS1 cases should not be interpreted as higher-level (collective) selection in a realist sense.

Conclusion

We should accept global realism with MLS1 cases understood as lower-level (particle) selection.

Section 2 sets out the case for P1, Sect. 3 sets out the case for P2, and Sect. 4 sets out the case for P3.

It is important to stress, before we begin the argument, that the form of pluralism I shall be attacking is a quite specific, and explicitly conventionalist (anti-realist) view concerning only the units of selection.Footnote 6 I am not suggesting either that other forms of pluralism in the philosophy of science and the philosophy of biology must be conventionalist views, or that my arguments in any way carry over to them. In other cases pluralistic views may be consistent with realism (e.g. pluralistic realism about species concepts, Dupre (1981), Kitcher (1984) Boyd (1999)). And there is no reason that I can see one why one could not reject conventionalist pluralism about the units of selection of the type I discuss while embracing other forms of pluralism such as, for example, pluralism about species concepts (ibid.), pluralism about functional explanation (Godfrey-Smith 1993), or more general pluralistic views about science such as those defended by Dupre (1993), Mitchell (2003) or Shaw (2016).Footnote 7

The final introductory point I shall make is that my view is potentially distinctive in two ways. Firstly, most who have argued that MLS1 is lower-level selection have done so because they wanted to be reductionists, and deny the reality or importance of all group and higher-level selection. But I am happy to accept the hierarchical, multi-selectionist view.Footnote 8 It’s just that I advocate a more stringent requirement on higher-level selection than has typically been accepted by multi-selectionists. This will, as we’ll see, deny the status of higher-level selection to all the MLS1 models that are advertised as group selection models; but I can accept the reality and importance of MLS2 processes such as species selection, superorganism group selection, and so on.

My view is also somewhat distinctive in that the most prominent global realists in the realism-pluralism debate, such as Sober and Wilson (1998), have understood MLS1 as collective selection (with the particle selection construal interpreted instrumentally). Few global realists interpret MLS1 as I do, as particle selection (with the collective selection perspective interpreted instrumentally). In other words, I advocate an unusual combination of global realism, multiselectionism, and MLS1-interpreted-as-particle selection.

The MLS1-MLS2 distinction has been discussed and deployed in much of the recent literature on the units of selection, but hasn’t, as far as I’m aware, been pressed into service to support a general metaphysical view regarding realism and conventionalism about the units of selection. That is what I aim to do here.

Against global pluralism

Global pluralism will be shown to be false if we can show that, for some cases, realism with respect to a process of selection acting at a particular level is unavoidable. In order to establish this, we need to (a) identify sufficient conditions for selection acting at a level where the process is not re-describable in terms of selection acting at some lower-level, and (b) show that these conditions are satisfied in nature.

Fitness in MLS2 and conditions for natural selection

It might seem that MLS2 processes, as Okasha describes them, give us the sufficient conditions we require: There is evolution by natural selection at level L if there is heritable variation in fitness2 among entities at L. After all, unlike in MLS1, in MLS2 our focus is on the evolution of collective-level characters through differential higher-level fitness that is irreducible. As Okasha writes, ‘…in MLS2, group selection affects the evolution of a group character, not an individual character; so there is no way that an ‘individualist’ re-description is possible. This ties in with the point that pluralism is only a theoretical option in relation to MLS1, for only there is it possible to describe the overall change in both multi-level and single-level terms’ (ibid, loc. 2505). (MLS2 processes (as the name implies) are usually discussed as examples of group, species and higher-level selection, but the concept easily generalises to any level in the hierarchy at which entities reproduce, giving rise to other entities of the same kind. MLS2 processes operate at the multicellular organism-level, for example (Michod 1999, 2005). I return to this point below.)

In fact Okasha’s own discussion (2006, ch. 3) shows why MLS2 processes on their own do not provide us with sufficient conditions for irreducible selection acting at a particular level. This is because of what he calls ‘cross-level by-products’ in MLS2. Consider some level L. In some cases differential success of entities at level L, where this is understood in terms of fitness2 differences, is entirely a by-product of fitness differences, and selection, at a lower-level. Thus, Okasha suggests, for selection at a level there needs to be a causal, not just statistical connection between character and fitness at the appropriate level. Fitness-character covariance can be result of a causal relation between character and fitness, or can be a result of (by-product of) lower-level fitness.

Take the classic case of the evolution of running speed in zebras (Williams 1966). Fast herds of zebras may give rise to more groups than slow herds (assuming the herds can reproduce, which may be questionable (Godfrey-Smith 2009)), and thus have higher fitness2. There is covariance of zebra group character (group fleetness) and zebra group fitness, but this is a by-product of fitness and selection at the level of individual zebras; it is a merely statistical connection/correlation: the group character does not cause the group fitness. Species sorting is another example of this (Vrba and Gould 1986).Footnote 9 This is an MLS2 process. The differential fitness of species that is a product of lower-level selection processes can be fitness2: some species do better than others in the sense of leaving more offspring-species; but, although this kind of fitness is not defined in terms of lower-level fitness, this can be (mere) species sorting rather than species selection if it results from selection on individuals. If species A has higher fitness2 than species B merely because the members of A have higher average fitness than the members of B – that is, because species A has higher fitness1 than species B – the fitness2 differences are a cross-level by-product, and we are dealing with mere species-sorting, not selection. There will be some (aggregate) species-level trait that is correlated with success or failure characterised in terms of fitness2, but in species sorting the species-level character does not cause the fitness2 of the species; the latter is caused rather by the fitness of the individual members of the species. (While mere sorting has been discussed primarily at the species-level, it easily generalises to any collective level. From now on by ‘sorting’ I shall mean sorting at any level.)

The point is that although fitness2 is defined independently of fitness1, the two can be aligned: fitness2 is defined independently of fitness1, but can still be entirely the result of fitness1, and lower-level selection. This suggests, as Okasha notes, that fitness2 differences are not a sufficient condition for selection at L: it also needs to be the case that the differences are not a by-product of lower-level processes – there must be irreducible causal processes at the higher-level where this goes beyond just fitness2 differences: there needs to be the causal connection between character and fitness.

This, then, suggests generalised sufficient conditions for selection at a level –

There is selection at level L if there is heritable variation in fitness2 among entities at L, and the character-fitness covariance at L is causal.Footnote 10

Thus it isn’t quite right to suggest, as Okasha does, that in MLS2, ‘there is no way that [a lower-level] … re-description is possible’, because in MLS2, collective selection affects the evolution of a collective, not a particle character (ibid., loc. 2505). If the fitness2 differences at the collective level are just a by-product of particle-level selection, then there is no collective-level selection at all, and presumably a particle-level re-description in such cases, at least with respect to the relevant causes, is not only possible but mandatory. In cases of species sorting, for instance, the differences in fitness2 among species, while not themselves being strictly reducible to fitness1 differences (as by definition fitness1 and fitness2 are characterised differently), are nonetheless entirely a by-product of selection on individuals, so that the species ‘selection’ must be re-described as an individual-level selection process, albeit one that may influence collectively characterised traits, and have macroevolutionary effects. Here, the collective (species) selection is spurious.

As noted above, MLS2 processes are standardly thought to apply to ‘higher-level selection’, or at least levels where collectives produce other collectives, and I have not always been able to avoid talking in these terms, but this is an artefact of the history of the concept, and is not (or should not be) built in to the very concept of MLS2 selection. What matters for MLS2 is that the fitness of entities at a level is understood in terms of the generation of more entities of that type (at that level) whether or not these are collective entities. (This contrasts with MLS1: since the fitness1 of an entity concerns the fitness of the particles within it, it only applies to collective levels.) Thus the above sufficient condition equally applies to non-collective levels. If genes are not collectives in the relevant sense, they may still possess fitness2, understood as their propensity to replicate, i.e. produce more copies of things like themselves. (Of course, in such a case the fitness of the entities will be trivially irreducible, since there is nothing it can be reduced to.)Footnote 11

Emergent fitness and emergent characters

Some, such as Vrba (1984, 1989), have maintained that, at least in the case of species selection, my proposed sufficient conditions are not in fact sufficient. For species selection to take place, there also need to be emergent (not just aggregate) species-level characters.Footnote 12 Whether this is required for species selection, or whether emergent species fitness is sufficient, has been the subject of an ongoing debate. Lloyd (1988), along with Okasha (2006), Gould (2002) and Grantham (1995), deny that emergent traits are necessary, and I think they are correct. Take two species of horses, one small-bodied and one large-bodied. Large-bodied horses may have a competitive advantage over small-bodied horses at the organismic level, such that (a) within each species larger body size is selected for, and (b) the larger-bodied species contributes more individuals to subsequent generations that does the small-bodied species (it has higher fitness1); yet the small-bodied species may speciate more rapidly than the large-bodied species (it has higher fitness2). Unlike in the zebra case, the aggregate species character (being a small species) is the cause of the fitness2 of the species. This can give rise, under the right conditions, to a cladogenetically-driven trend of decrease in body size in the horse clade (Grantham 1995). In such a case individual selection and species selection are pushing in opposite directions (a sufficient, but not a necessary condition for higher-level selection). Whether this has actually happened is of course an empirical question, but it is seemingly coherent as a species-selection scenario. Yet average body size is plainly an aggregate, not an emergent trait of horse species. Species selection happens when species fitness is caused by species characters, and the species fitness is not reducible to individual (lower-level) fitness (i.e. the evolution of the character is not explainable in terms of selection at lower-levels), whether the species character is emergent or aggregate (which is not to deny that cases that involve emergent species characters are the paradigm cases of species selection).

Again, this point generalises to selection at any level. The generalised version of Vrba’s requirement would be that for selection to take place at level L, there must be emergent characters at L. But that is too strong.Footnote 13 For there to be genuine selection at level L, it is not necessary that there be emergent characters at L, only that there be emergent, irreducible fitness defined at L. The criterion for selection acting at level L is that the fitness of entities at level L is caused by level-L characters, and this fitness is not reducible to the fitness of entities at level L-n (i.e. the evolution of the character not explainable in terms of selection at lower levels). For this irreducible (emergent) level L characters are not required.

It is true that at levels other than the species-level – the organism level, for instance - there may not be many non-emergent traits that cause irreducible fitness, in which case the differences between Vrba’s view and the one I favour would not show up at that level. When there is irreducible fitness at the organism-level, it is likely to be caused by emergent organism traits. Organisms are highly cohesive, integrated, and tightly organised entities, such than many of their traits are good candidates to be emergent characters– ‘more than the sum of the parts’. The cases where the two views disagree, i.e. cases of aggregate traits at a level causing irreducible fitness differences at that level, may be found predominantly at the species, and perhaps the deme, level. Thus it is likely that my first premise (that global pluralism is false) could be established even if we accepted Vrba’s requirement: whether her more stringent conditions are ever met in the case of species – and this is an open question – it is very plausible that they are met at other levels, such as the organism-level, and all we require to establish P1 is some case or other of irreducible selection at a level. It is nonetheless preferable to work with the less restrictive view, not only because it is more plausible in itself, but because, for the purposes of my argument, firstly, if it turned out that no characters at any level were emergent (and this metaphysical claim, however implausible, can’t be entirely ruled out in advance), my argument for P1 would fail, if it relied on Vrba’s criteria. And secondly, we can thereby sidestep the vexed question of how to define ‘emergent character’ (Turner 2011).

MLS2 processes in nature

Recall our sufficient conditions:

There is selection at level L if there is heritable variation in fitness2 among entities at L, and the character-fitness covariance at level L is causal.

If these conditions are satisfied, there is collective selection which is not reducible to particle selection (more generally, there is irreducible selection at a level), and thus realism is unavoidable with respect to it, and pluralism is ruled out. But are the conditions ever satisfied? Species selection is the paradigm case of MLS2 (Demuth and Heisler 1988), but, while there are theorists who believe that our two conditions are often met in the case of species, and thus that species selection is a real and important phenomenon, this is a controversial, and seemingly a minority, position. So it would be unwise to tie our argument against global pluralism too closely to the empirical case for species selection.Footnote 14 But we don’t need to. We have an MLS2 process whenever there are heritable fitness2 differences and this may occur at any level in the hierarchy. Two, perhaps more plausible, examples of processes satisfying our two conditions are the evolution of superorganisms (e.g. ant colonies) and, most obviously, individual organisms.

As Sterelny notes (1996), the most persuasive example of genuine, irreducible group selection has always been the evolution of organism-like colonies in the eusocial insects – ant colonies, termite colonies, etc. – classic ‘superorganisms’. There are two reasons, he suggests, for taking superorganism evolution to be irreducible group selection, with respect to which a particle-level description is unavailable. Firstly, superorganisms display a degree of cohesion, integration, and functional specialisation that approaches that of individual organisms, and thus have almost as strong a claim to be considered objective vehicles/interactors as do individual organisms. Secondly and relatedly – and this is the key point for our purposes - we have reason to think the fitness of superorganisms varies independently of the fitness of their component organisms – in our (but not Sterelny’s) terms, it is fitness2, in which the fitness of the nest or hive has been completely decoupled from the fitness of its individual members: the hive or nest has fitness2 in its own right, not as a by-product of its fitness1. Thus, if he is right, superorganism evolution is an example of our sufficient conditions being satisfied in nature. It follows that global pluralism is false.

And finally and most convincingly, the work of Michod (1999, 2005) and Michod and Roze (1999) suggests (a) that our two conditions are the appropriate criteria for genuine selection to occur at the level of individual multicellular organisms (indeed, for it to be meaningful to speak of such organisms existing as evolutionary individuals at all), and (b) that the conditions are often satisfied at the individual organism level (see Okasha ibid. loc. 3066 for discussion). If they are right about (b) – and I take their claim to be relatively uncontroversial - there is often selection at the level of multicellular organisms that is not reducible to lower-level (e.g. cell) selection. Again, it follows that global pluralism is false.

Against local pluralism

Local pluralists are pluralists about at least some selective episodes. This is of course consistent with being a global pluralist, but by ‘local pluralism’ I will mean the view that realism is true of some episodes (global pluralism is false) and pluralism is true of others. One salient view here is realism with respect to MLS2, combined with pluralism with respect to MLS1. Local pluralism in this sense has been defended by Sterelny and Griffiths (1999). In this section I claim that some key arguments for local realism are consistent with global realism. I shall consider two important arguments for local pluralism: Sterelny and Griffiths’ stance-dependence argument, and a diachronic-vagueness argument suggested by Okasha’s analysis of the major transitions in evolution. Footnote 15

Stance-dependent interactors and local pluralism

In this section and the next I consider arguments for local pluralism, and suggest that they do not in fact support that position. Sterelny and Griffiths (1999), for example, argue that some groups, such as superorganisms (ant colonies and the like), count as objective interactors, and thus objective agents of selection, while others, such as temporary trait groups, loose coalitions, and so on, are at most ‘stance-dependent’ interactors and agents of selection – we can take the ‘interactor stance’ towards them, just as, according to Dennett (1987), we can take the ‘intentional stance’ towards certain systems. But just as the intentional stance is, according to Dennett, justified in pragmatic terms – in terms of whether it is useful in predicting the behaviour of the system, irrespective of whether the system is ‘really’ an intentional system - the interactor stance is also justified pragmatically. It may seem that this argument supports local pluralism: pragmatist-pluralism is true of some groups, and some selective episodes, but false of others. But it does not. It is perfectly consistent with global realism that groups that are not in fact interactors, in an objective sense, can be treated as if they are, if doing so is theoretically or pragmatically fruitful. On this way of looking at it, in MLS1, the particles are the agents of selection (i.e. the interactors) in an objective sense; but the collectives can be treated as if they are agents of selection (they are stance-dependent interactorsFootnote 16). Similarly, most commentators interpret Dennett as claiming that nothing is really an intentional system, but certain systems can be usefully interpreted as if they are. So thermostats are not actually intentional systems, but it can be useful to treat them as if they are (i.e. it’s not that there is no fact of the matter about whether they are). In other words, it is not the case that, as Sterelny and Griffiths claim, there is no fact of the matter about the interactors or the units of selection in the relevant cases. Rather it is a fact that the particles, and not the collectives, are the interactors, and the selection at work is particle, not collective selection. This is of course consistent with modelling the process as collective selection, with the model then interpreted instrumentally, i.e., as a useful fiction. (This is the reverse of Sober and Wilson’s view (1998) that in MLS1 the groups are the agents of selection, with selection acting on the collectives, but the process can be modelled as a particle-level process, so long as this is interpreted instrumentally – as useful for predicting what will evolve, but not as accurately capturing the actual causal process at work.) In Sect. 4 I will argue that this is indeed how we should understand MLS1 processes – as particle, not collective selection. For now I wish merely to show that Sterelny and Griffiths’ arguments for local pluralism are consistent with global realism.

Okasha on the major transitions

A different kind of argument for local pluralism can be derived from Okasha’s discussion of MLS1 and MLS2 processes in the context of the major transitions in evolution (Okasha ibid., ch. 8). These are the watershed, ‘game-changing’ moments in the history of life that involve the origin of individuals at new, higher levels, such as the origin of the eukaryotic cell, or the origin of multicellularity (Maynard Smith and Szathmary 1995), and about which there has been an explosion of interest in recent years (see e.g. Calcott and Sterelny 2011, Clarke 2014, Bourrat 2015, Currie 2019, Ryan et al. 2016, O’Malley and Powell 2016, Wu and Banzhaf 2011, Okasha 2022).

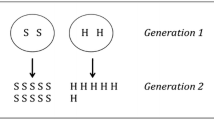

Okasha plausibly suggests that a key message of work on this topic is that rather than being, as they had tended to be thought of previously, two different, unconnected processes, MLS1 and MLS2 processes should, in the light of the major transitions, be understood as two temporal stages in the one historical process of the emergence of individuality and independent fitness at higher levels of biological organisation. The major transitions are characterised by the gradual transition from (1) particles acting entirely independently, to (2) particles interacting co-operatively, and forming pseudo-, or proto-collectives, in which the fitness of the ‘collective’ is defined as average particle fitness (MLS1); to (3) a stage in which the fitness of the emerging collectives can be defined independently of the fitnesses of the particles but is nonetheless determined by them, and finally to (4) the emergence of genuine collectives, with collective-level functions, overall integration, cohesion and coordinated activity, in which the interests and activities of the particles are subordinated to the interests and activities of the collective, and in which the fitness of the collective is not determined by the fitnesses of the particles – MLS2 (Okasha 2006). Fitness has at this final stage been transferred, or ‘exported’, from particle to collective. As Michod discusses (1999, 2005), the transition from 2 to 3 to 4 depends crucially on the evolution of mechanisms for the suppression of competition among the particles, reducing the possibilities of the collective breaking down due to subversion from within by selfish free-riders.Footnote 17

It follows from this analysis that there is a period of indeterminacy (the third stage) while an MLS1 processes (stage 2) is transformed into an unambiguous MLS2 process (stage 4) – the period during which the fitness of the collective is not defined as average particle fitness but is proportional to it. ‘There is bound to be a period of indeterminacy during which it is unclear whether genuine collectives exist or not; how to classify selection processes that occur during this period will be similarly indeterminate’ (ibid., loc. 3131). What is going on during this phase is neither clearly an MLS1 process nor clearly an MLS2 process; it is a grey area in between. In this paper I argue (see below) that MLS1 processes are lower-level selection processes, while MLS2 processes are (or can be) higher-level selection processes. Thus, if Okasha is right, there are seemingly some processes that are intermediate between lower-level and higher-level selection processes, such that it is indeterminate whether to count them as higher or lower-level selection processes. Although Okasha doesn’t explicitly draw a pluralist moral from this, it is easy to see how one could: during the phase in question, there is no fact of the matter about whether what is happening is lower or higher-level selection; thus lower-level and higher-level selection models (MLS1 and MLS2) are equally acceptable models of this process.

It is important to see that this pluralist challenge applies even if we accept, as I suggest we should, that MLS1 processes are objectively lower-level selection processes, and MLS2 processes are (or can be) objectively higher-level processes. As we have seen, Sterelny and Griffiths suggest that MLS1 processes themselves are subject to pluralism; even if we reject that, we still need to consider the period of indeterminacy in between MLS1 and MLS2 processes, as grounds for local pluralism.Footnote 18

The first point to make here is that we in fact have a ready means of classifying the intermediate stage: it is MLS2-sorting. Recall that in MLS2-sorting, collectives reproduce, the fitness of the collectives is fitness2 (average number of offspring groups), but this fitness is entirely determined by the fitness of the particles (fitness2 is a function of fitness1). The period of temporal intermediacy between MLS1 and MLS2-selection is, it would seem, MLS2-sorting. And we have seen that MLS2-sorting should be understood as lower-level (particle) selection, not higher-level (collective) selection. Even if, as Okasha sometimes suggests, the third phase can be modelled as either MLS1 or MLS2-sorting, this needn’t imply indeterminacy or pluralism between particle and collective selection, since both of these count as particle selection.

But, it will be objected, surely the general gradualness of Darwinian processes, and the fact that Darwinian processes themselves evolve (Godfrey-Smith 2009), entails that there will be a transitional phase between the MLS2-sorting phase and the MLS2-selection phase. It would be most implausible to posit a sharp boundary here, when MLS2-sorting instantly becomes MLS2-selection. The autonomy of fitness2 in relation to fitness1 presumably emerges gradually. Perhaps here we have a good candidate for an intermediate stage between particle and collective selection.

I can accept this, as it is no part of the global realist thesis I am defending that there is never any indeterminacy between particle and collective selection. For, from the fact that there are processes which are neither determinately lower-level nor determinately higher-level selection processes it does not follow that these processes can be modelled as either lower-level or higher-level selection and that these may be both be maximally correct (model pluralism). The assertion of vagueness is different from, and doesn’t necessarily support, conventionalist pluralism (Boucher 2020). Vagueness in the relevant sense here is a realist idea: that as a matter of objective fact, for some processes it is indeterminate whether they are higher-level or lower-level processes. Model pluralism, on the other hand, is an anti-realist, or conventionalist, idea, as we have seen. Okasha’s approach is emphatically a realist one: MLS1 processes are real processes in nature, as are MLS2 processes, and it is also a fact about nature that some processes are intermediate between the two, as one changes gradually into the other. This fits the realist-vagueness perspective, which allows for occasional absences of fact concerning the classification of certain processes or phenomena; but it fits ill with the pluralist-conventionalist perspective that would regard the question of how to classify these processes as purely one of convention or pragmatic utility.Footnote 19 Thus the vagueness Okasha points to does not threaten global realism about the units of selection, as long as this realism can accommodate vagueness and indeterminacy, as any realist view of Darwinian processes should. In a sense it is still the case that there is always a fact of the matter about the units of selection, it’s just that sometimes it is a fact of the matter that the process in question is neither determinately lower nor determinately higher-level selection.Footnote 20

In this section I have considered two arguments for local pluralism, and concluded that they fail: they are consistent with global realism. The failure of these arguments to establish local pluralism does not of course show that local pluralism is false. But in the absence of convincing arguments for it, we ought, I’d suggest, to accept global realism, as the more metaphysically unified and simple view.

The incoherence of local pluralism

The local pluralist’s attempt to combine realism in some cases with conventionalist instrumentalism in others, is of doubtful coherence (see Boucher 2020). In Sterelny and Griffiths’ version, when selection acts on organisms, or superorganisms, there are facts concerning the level at which selection acts, but when it ‘acts’ in population-structured trait-group evolution, such facts drop out of the picture, and we may adopt whatever perspective we find most useful in modelling the process. But this is hard to make sense of. One way to bring this out is the following. When, in a case X of organism selection, we utter ‘the organism was the (or a) unit of selection in X’, the predicate ‘unit of selection’ picks out a property that something in X (i.e. organisms) possesses, and our utterance possesses truth conditions that obtain. But when, in a case of population-structured evolution Y, we utter a sentence of the form ‘U was the (or a) unit of selection in Y’, ‘unit of selection’ expresses a property that nothing in Y possesses, as a matter of objective fact, and all such utterances thus possesses truth conditions that do not obtain, and so are false, strictly speaking, though perhaps some are ‘useful fictions’. This combination of realism for some selection contexts with an error-theoretic interpretation of all units of selection talk with respect to other selection contexts may not be logically contradictory, but it is, to say the least, a strangely disunified view about the metaphysics of evolution (Sober 2011, 167). It suggests that local pluralism is fundamentally unstable, and that if we aspire to a more metaphysically unified view we need to choose between global realism and global pluralism. In the previous section I argued we should reject global pluralism. By disjunctive syllogism, it follows that we should accept global realism.

MLS1 as particle selection

In Sect. 2 I rejected global pluralism, and in Sect. 3 I rejected local pluralism. It follows that we should accept global realism. But the truth of global realism leaves open the important question of the status of MLS1 processes: are they examples of collective or particle selection? In this section I shall argue for the latter claim.

In the standard MLS1 trait-group model, individuals, as part of their life cycle, form temporary groups (particles form temporary collectives) that provide an environment – a population-structure – in which interactions take place that affect their fitness. The groups form assortatively (i.e. non-randomly: like assorts with like). The groups do not persist, or reproduce as groups; the individuals later re-join the larger population, reproducing as individuals. Groups that have a larger proportion of individuals with the character of interest (e.g. altruism) contribute more individuals to subsequent generations, i.e. have higher fitness1, as a result of individuals with that character giving a fitness boost to all members of their group, even if within each group, such individuals are themselves at a selective disadvantage vis-à-vis selfish types.

That such an MLS1 process is fundamentally particle, not collective, selection, is implicit in much of the discussion of MLS1. For instance, Wu and Banzhaf write,

If we are interested in the changing frequencies of different individual traits, individual entities will be the objects of evolution; group entities are only a structure or an environment where fitness-affecting interactions take place. Most multilevel selection models proposed for the evolution of cooperation … belong to this kind. These models focus on how to propagate the altruistic trait among individuals in a population. (2011) [Emphasis added.]

What is striking in this passage (and many others in the literature could have been cited) is Wu and Banzhaf are saying that in MLS1, groups are merely ‘a structure or an environment where fitness-affecting interactions take place’, rather than being interactors in their own right.Footnote 21 That is, in MLS1 individuals are selected on the basis of differential fitness, where their fitness is determined in part by the particular population structure they find themselves in. The view that groups are ‘aspects of the context or environment’ is part of the individualist framework (Godfrey-Smith 2006, 376). Note that Wu and Banzhaf do not say that this individualist construal is merely one possible interpretation of MLS1 processes (as conventionalist pluralism would have it). Rather, this is what MLS1 processes are.Footnote 22

More specifically, there are three related reasons for treating MLS1 as particle, not collective selection: the reducibility of collective fitness; the lack of collective reproduction; and the dispensable role of collectives in MLS1.

Reducible fitness

Recall that in Sect. 2 I offered the following sufficient conditions for there to be genuine selection at level L:

There is selection at level L if there is heritable variation in fitness2 among entities at L, and the character-fitness covariance at L is causal.

This was intended to capture to intuitive idea that the criterion for selection acting at level L is that the fitness of entities at level L is caused by level-L characters, and this fitness is not reducible to the fitness of entities at level L-n (i.e. the evolution of the character not explainable in terms of selection at lower-levels).

One argument for the claim that MLS1 is particle, not collective selection, is simply that the above conditions are individually necessary as well as jointly sufficient for selection at a level:

There is selection at level L only if there is heritable variation in fitness2 among entities at L, and the character-fitness covariance at L is causal.

Now I may of course be open to the charge of begging the question here, given that what is at issue is precisely whether MLS1 processes can count as collective selection, and I am declaring that they can’t by definition, as it were. But this necessary condition is well-motivated. As I noted in Sect. 2, this criterion has been discussed primarily as a criterion for species selection, but it very naturally generalises to a plausible set of necessary and sufficient conditions for selection to act at a level. For the purposes of the argument of this section, the requirement of fitness2 differences is what matters. This is all we need to rule out MLS1 processes as examples of collective selection. We have seen that level L fitness2 differences are not sufficient for selection at L. Okasha shows why we also need the causal covariance condition, given the possibility of cross-level by-products. Others, as we have seen, go further, claiming that emergent traits are also required. I followed Okasha and Lloyd in rejecting that further claim. But for the purposes of this section, these arguments can be set aside, since establishing the necessity of fitness2 differences is enough to declare MLS1 processes lower-level selection. The necessity of fitness2 differences is accepted by all when it comes to species selection. My claim is that this very naturally generalises to give us a necessary condition for selection at any particular level. After all, for multiselectionists, there is not supposed to be anything special about the species level. It is merely one level among many at which selection takes place. If we have a necessary condition for selection to act on species, why would not this also serve as a necessary condition for selection to act at any level in the hierarchy?

The need for fitness2 differences at any level L arises for the same reason that we require fitness2 differences in the case of species selection. Without them, fitness and selection are reducible to fitness and selection at lower-levels. Thus, to the extent that there is collective fitness represented in MLS1, it is defined as average particle fitness. So it is reducible to particle fitness. Hence MLS1 is not really higher-level selection. Note that in a sense fitness2 is also reducible to lower-level fitness if it is just a by-product of lower-level fitness, or by-product of fitness1. In such a case it is defined independently of fitness1 but is entirely determined by it. That is why L-level fitness2 differences are not by themselves sufficient for selection to act at L. But as I noted, once we accept the necessity of fitness2 differences, we have already established that MLS1 does not qualify as higher-level selection. Genuine selection at a level requires (at least) fitness defined for that level (not reducible to lower-levels) – i.e. fitness2. So for selection to occur at a level, there must be fitness2 differences at that level. Fitness1 always pertains to selection operating at the level of the particles, not the collective.

Reproduction and heritability

Part of the claim that fitness2 differences are necessary for selection at a level is the idea that for selection to take place there must be unambiguous reproduction at that level (Maynard Smith 1976). This follows from two relatively uncontroversial claims: that for selection to happen at a level there must be heritability defined at that level (as there must be heritable variation in fitness at that level), and that reproduction is required for heritability. As we’ve seen, by definition in MLS1 collectives don’t reproduce, only the particles. In the trait group model, groups are formed, then dissolve, and later are formed again, but the earlier and later groups do not stand in ancestor-descendant relations, or form lineages, unlike, for example, the way one species may be ancestral to another. Given the above assumptions, it follows that there is no heritability at the collective level in MLS1, and therefore that MLS1 is not collective selection.Footnote 23

There are three options for those who want to interpret MLS1 as higher-level selection (Okasha, Sect. 6.4). Firstly, one may accept the claims that heritability is required for selection, and that reproduction is required for heritability, but claim, contrary to the way MLS1 is usually defined, that collectives do in fact reproduce in MLS1 (Sober and Wilson 1998). But this stretches the notion of reproduction to breaking point, and would seem to collapse the distinction between MLS1 and MLS2, upon which our whole discussion, and most recent work in this area, is based.

Secondly, one may accept that heritability is required for selection, and accept that collectives don’t reproduce in MLS1, but deny that collective reproduction is required for collective heritability. Heritability (at least, heritability in MLS1 – what Okasha (2006) calls collective heritability1) may be understood, for instance, in terms of the resemblance between a group and the set of individuals it produces (Okasha ibid.). But this move seems somewhat ad hoc. If the first option involved stretching the concept of reproduction, this option involves a similar stretching of the concept of heritability.

Thirdly – and this may be a notational variant of the second option - one may deny that collective heritability (of any sort) is required for collective selection (Sober 1987): all that is needed is particle heritability. But this would seemingly mean abandoning the classic heritable variation in fitness account of the conditions for selection, which seems a high price to pay for being able to call MLS1 collective selection.

We should, I suggest, accept the simple principle (deriving from Lewontin’s classic abstract characterisation of natural selection) that for there to be selection at a level, entities at that level must reproduce, and pass on their traits, allowing for heritability at that level, in the traditional sense (see Godfrey-Smith 2009, ch. 6). More could be said here; I’ve only been able to touch on these arguments briefly. But the difficulties of squaring the apparent lack of genuine reproduction and heritability of collectives in MLS1 with the standard account of the conditions for natural selection contribute to the case against seeing MLS1 as collective selection.Footnote 24

Dispensable collectives

Godfrey-Smith (2009), following Maynard Smith (1976), has pointed out that in MLS1 processes, discrete groups (collectives) need not even exist for the process to work, and for the characters of interest to evolve. The requisite fitness-affecting interactions among the particles can be instantiated within a continuous lattice-like structure, rather than a group-structure. In the model the population of individuals regularly forms and then dissolves the lattice structure, with each individual interacting only with its immediate neighbours when in the lattice. The bearers of the altruistic trait still give a fitness boost to their neighbours, such that it pays to be surrounded by that type (while being surrounded by selfish types lowers one’s fitness). As long as like tends to associate and interact with like (e.g. altruists with altruists, selfish types with selfish types), the same evolutionary dynamics as in group-structured MLS1 can emerge: ‘Groups are replaced, in a sense, by neighborhoods. But there are as many neighborhoods as there are individuals. Neighborhoods, unlike groups, cannot be seen as collectives competing at a higher-level’ (2009, 118). The implication is inescapable: if collectives as such are not even required for MLS1 to operate, MLS1 cannot fundamentally be collective selection. In Godfrey-Smith’s terms, it is particle selection driven by correlated interaction: group structure is merely one way among others that the required interactions can be brought about.Footnote 25

Okasha’s arguments for interpreting MLS1 as collective selection

Okasha offers two arguments for thinking of MLS1 as genuine collective selection. His first argument is that those putting forward MLS1 models have thought that what they were doing was offering models of collective selection. If MLS1 is particle, not collective, selection, they would all be wrong about this, which is an unfortunate conclusion (ibid., loc. 778). This doesn’t appear to be a strong argument (Okasha accepts it is not decisive). While MLS1 has often been interpreted as collective selection – indeed it is the ‘classic’ form of collective selection – it has also, as we’ve seen, been widely interpreted as context-dependent particle selection. We need to consult our reasons for treating it as collective or particle selection, whatever others have thought about this.

His second argument is that ‘[a]lthough MLS1 treats the particles as the focal units, it can nonetheless shed light on collective-level phenomena. For since collectives are composed of particles, explaining the evolution of a particle character could help explain salient features of collectives too’ (loc. 783–785). But the ability to shed light on collective-level phenomena seems too weak a condition for treating MLS1 as real collective selection. MLS2-sorting, as we’ve seen, is also a process that has collective-level effects, and can shed light on collective-level phenomena. But Okasha himself rejects the idea that it thereby qualifies as collective selection. The case for treating MLS1 as collective selection is even weaker.

Similarly, Okasha writes, ‘although particles are the focal units [in MLS1], a selection process at the collective level does occur - the collectives make differential contributions of particles to the next generation’ (loc. 820–821). But so long as the process whereby collectives make differential contributions of particles to the next generation can be re-described (as Okasha accepts it can for MLS1) in terms of lower-level fitness and selection, we need not call this ‘a selection process at the collective level’, strictly speaking.Footnote 26

Conclusion

This completes the argument. To sum up, in Sect. 2 I argued (P1) that Okasha’s analysis of fitness in MLS2, and cross-level by-products, can be combined with the standard heritable variation in fitness account of evolution by natural selection, to yield plausible sufficient conditions for selection at a level. I then suggested that it is very likely that such conditions are satisfied at some levels, thus ruling out global conventionalist pluralism. In Sect. 3 (P2) I argued both that some key arguments that can be gleaned from the literature in support of local pluralism do not convince, being consistent with global realism, and that local pluralism yields an unsatisfactorily disunified (bordering on incoherent) picture of the metaphysics of selection. The rejection of global pluralism (P1) and local pluralism (P2) leaves global realism as the surviving option. In the final section (P3) I argued that MLS1 should be understood as particle, not collective selection, due to three features of MLS1: the reducibility of collective fitness, the absence of collective reproduction, and the dispensable role of collectives. I conclude that we should accept, as a plausible general metaphysical picture of the units of selection, global realism with MLS1 understood as particle selection.

Notes

Within the pluralist camp pluralistic gene selectionists hold that while multiple representations of selection processes are generally available and permissible, the genic perspective on the units of selection should be privileged as providing the most general account of evolution. See Kitcher and Sterelny (1988); see Wilson (2005) and Lloyd (2005) for discussion and critique.

I follow Okasha (2006) in talking of ‘collectives’ and ‘particles’ rather than ‘groups (of organisms)’ and ‘individuals/organisms’ because MLS1 and MLS2 don’t just apply to the latter: in some contexts individual organisms are the ‘collectives’, with their constituent cells being the ‘particles’, for example.

As an anonymous reviewer pointed out, the MLS1-MLS2 distinction is not universally accepted. But it is, it seems to me, fairly widely accepted, thus it can be assumed for the purposes of the argument of the paper.

Of course, the realist may hold that in MLS1, when selection acts on collectives, it also acts separately on particles (for instance, favouring collectives of altruists while favouring selfish types within collectives). What the realist cannot say is that the collective selection itself can be modelled as particle selection, with only pragmatic differences between them, in the model pluralist sense.

Global pluralism is defended by Sterelny and Kitcher (1988), Kitcher et al. (1990), Dawkins (1982), Kitcher (2004) and Waters (1991, 2005). Local pluralism is defended by Sterelny and Griffiths (1999), and Dugatkin and Reeve (1994). Global realism with MLS1 interpreted as collective selection is defended by Sober and Wilson (1998, 2002). Okasha’s view is a little hard to pin down. He rejects global pluralism. He argues in some places that MLS1 is really collective selection, but elsewhere says he is open to at least the ‘possibility’ of pluralism with respect to MLS1. If pressed I suspect he would endorse local pluralism.

Sterelny and Kitcher (1988, 359) are explicit that what they are arguing for is a kind of ‘instrumentalism’, according to which certain putative entities, ‘targets of selection’, ‘do not exist’, while Kitcher (2003, p. xii) writes that: ‘there’s a constant danger of overinterpreting Darwin’s metaphor, so that there’s an alleged causal fact about the world concerning the exact place at which natural selection ‘acts’. Better, I believe, to see that selection is just our metaphorical way of approaching the complex facts of birth, mating and death; we can organise those facts in various Darwinian ways, and our choices among styles of organisation should be thoroughly pragmatic’.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer who urged me to clarify this point. This reviewer wondered why I wasn’t considering forms of pluralism such as Mitchell’s ‘integrative pluralism’ (2003). But conventionalist pluralism about the units of selection is, as I said, a very specific form of pluralism, and is seemingly very different from Mitchell’s view. Model pluralists are not saying the different models of the units of selection present partial and incomplete, but compatible models that need to be integrated into an overall picture. In MLS1, for instance, the model pluralist claim is that it can be modelled as collective selection, or as particle selection, and either of these is maximally adequate. It’s not that each gives a partial and partially correct picture and we need to integrate them, and show that they are compatible and complementary. It’s that there is no fact of the matter about which is objectively correct, so the biologist can pick the one that is most pragmatically helpful. But they are not compatible in Mitchell’s sense. The claim that in case X selection is operating on the collective, and the claim that in case X it is not operating on the collective but only on the particles, are incompatible and can’t in any sense be integrated (just as the relativist about morality does not think incompatible moral claims can or should be integrated). But they can be, in a sense, seen as equally correct if one adopts, like the model pluralist, a conventionalist view of the units of selection. Mitchell’s view seems closer to what I termed ‘unit pluralism’, i.e. the realist version of multi-level selection theory (‘a pluralism of models of causal processes which may describe contributing factors in a given explanatory situation’, Mitchell (1992, 142). She even appears to endorse unit pluralism in her (2004, 87). Conventionalist pluralism and integrative pluralism seem to be very different, indeed opposed, views, thus rejecting the former need not in any way force one to reject the latter.

I don’t however officially take a stand on this in this paper. The conclusions of the paper are consistent with, for example, the realist version of strict genic-selectionism. But they do not (as one anonymous reviewer worried that they do) imply that genic-selectionism is correct, and I trust it will be seen that in spirit the paper is in sympathy with multiselectionism.

More precisely, ‘sorting’ refers to differential species proliferation, with selection being one possible explanation for this. Sorting without selection is ‘mere’ sorting. (Vrba calls this ‘effect macroevolution’, though it may happen in standard microevolution.) From now on by ‘sorting’ I shall mean ‘mere sorting’.

This is a version of the ‘heritable variation in fitness’ account of the conditions for evolution by natural selection. This account, in one form or another, has been standard since Lewontin (1970). There are a number of questions that may be asked about its status and applicability, and how precisely it should be formulated – see Godfrey-Smith (2007, 2009). But it is widely enough accepted, at least in broad outline, that I can take it for granted here. I am interested in whether, given we accept this account, it can be combined with Okasha’s analysis to yield plausible general conditions for selection at a level.

So note that Okasha’s definition of particle fitness: ‘the number of offspring particles it leaves’ (loc. 717) is, aside from the words ‘particle’ and collective’, identical to his definition of collective fitness2: ‘the number of offspring collectives it leaves’ (loc. 720). There is one type of fitness here: the number of offspring of that type produced, which may apply to collectives, or particles that are not themselves collectives. This means that we need to qualify Okasha’s claim, discussed below, that MLS2 processes evolve out of MLS1 processes. This is not true of all MLS2 processes, but only those involving collectives.

There is also the problem that emergent characters at L are presumably typically a product of a selection process at L, i.e. L-level adaptations. But in that case, they cannot also be a precondition for such a process (Okasha 2006, loc. 1463).

I accept multilevel selection theory and the hierarchical expansion of NeoDarwinism, which is to say I think our sufficient conditions are in fact satisfied at multiple levels in the hierarchy, but all that is needed to establish the falsity of global pluralism is irreducible selection at a single level, so for the purposes of the argument of this paper I do not need to commit to the stronger claim about selection at multiple levels.

Sect. 3 builds on and develops the analysis in my (2020).

This suggests a weaker kind of pluralism from the conventionalist-pluralism I am rejecting: one that accepts a role for collective-selection, multi-level models so long as they are treated as useful fictions (just as Sober and Wilson (1998) accept a weak kind of pluralism, compatible with global realism, according to which individualist models of group selection are permissible so long as they are interpreted instrumentally; see Boucher 2020, Barrett and Godfrey-Smith 2002).

See Bourrat (2015) for an interesting critique of Okasha’s and Michod’s conception of evolutionary transitions in individuality.

Similarly, Sterelny (1996, 578) suggests there are likely to be borderline cases between population-structured evolution (MLS1) and superorganism evolution (MLS2).

Sober (2011, 167) also points out that occasional ‘borderline’ cases do not threaten the global realism he advocates. He does however accept conventionalist pluralism for the borderline cases, making him technically a local pluralist (though he claims, with tongue in cheek, that he is a realist ‘99.44%’ of the time). I am denying that conventionalist pluralism holds even for such cases.

Similarly, Wilson (2005) defends the view that higher and lower levels of selection are often ‘entwined’ such that there will sometimes fail to be a fact of the matter concerning the level at which selection is acting, but he sharply distinguishes this realist way of there being a lack of a fact of the matter from the conventionalist model-pluralist view. While his thesis is somewhat different from the temporal-indeterminacy thesis we are considering here (he thinks entwinement is a widespread phenomenon, not just a matter of occasional transitional borderline cases) it does highlight the fact that the acceptance of vagueness or indeterminacy can, indeed should, form part of the realist picture, and need not entail even local conventionalism (see also Boyd 1989).

Similarly Lloyd (2017) notes that ‘under MLS1, the lower-level particles are the interactors as well as the replicators, while in MLS2, both the upper level collectives as well as the particles are interactors.’ It is standardly thought that group selection requires groups to be interactors; more generally, that selection at Level L requires L-level interactors. If Lloyd is right, MLS1 processes involve particle, not collective, selection.

An anonymous referee expressed the worry that this view, which I endorse, involves a kind of eliminativism about MLS1. I don’t think that’s correct. The term ‘MLS1’ marks, in my view, a very real class of population-structured evolutionary processes that is theoretically extremely important. It is just that it is, in my view, particle, not collective selection. But it is not standard particle selection. It is particle-selection of a certain special kind, one where membership of a collective and the character of that collective, affects the fitness of particles within it. That is, I hold, a real and important phenomenon. Its discovery represented a great advance in evolutionary thinking. And I am a realist about MLS1: pluralists about MLS1 hold that MLS1 can be described equally as particle or collective selection. Realists hold that it is either collective selection, or particle selection, as a matter of objective fact. I hold that it is particle selection as a matter of objective fact. Of course if one thinks one can only be a realist about MLS1 if one regards it as collective selection, then I am not a realist about it. But I don’t see why we should accept that.

Maynard Smith (1987) argues that MLS1 processes cannot produce group-level adaptations, further weakening the case for regarding it as higher-level selection.

An anonymous reviewer expressed the concern that in treating MLS1 as particle selection, I was committed to denying that selection operates at multiple levels, and ultimately must accept something like the gene’s eye view. But this is not so. The view that I am defending allows that selection can operate at multiple levels. On my view there is selection at a level whenever the sufficient conditions I spelled out in Sect. 2 (pertaining to MLS2) obtain, and this may be the case at multiple levels. It is true that, as I say in footnote 8, the argument of the paper doesn’t rely on an answer to the question of which levels this is true of. But, as I also say in that footnote, my own view is that this is in fact true of multiple levels. The question of whether MLS1 processes count as collective or particle selection is a separate question. Even if they count as particle selection, we can still accept multi-level selection theory, so long as the sufficient conditions hold at multiple levels. Also, suppose that, say MLS1 group selection is really (as I argue) context-dependent selection on individual organisms. So long as that selection on organisms is an MLS2 process (at the organism level), there is genuine selection on organisms, and this does not reduce to genic selection. The reduction need not go all the way down in other words.

Jeler (2021) argues that if MLS1 is particle selection, selection must be operating on what he calls ‘belonging to’ properties, and that this idea is problematic. I do not have the space to address his arguments in this paper.

References

Arnold J, Fristrup K (1982) The theory of evolution by natural selection: a hierarchical expansion. Paleobiology 8(2):113–129

Barrett M, Godfrey-Smith P (2002) Group selection, pluralism, and the evolution of altruism. Philos Phenomenol Res 65(3):685–691

Boucher SC (2020) Pluralism, realism and the units of selection. South Afr J Philos 39(1):47–62

----Unpublished manuscript Two Kinds of Antirealism about the Units of Selection

Bourrat P (2015) Levels, time and fitness in evolutionary transitions in individuality. Philos Theory Biology 7:e601–e601

Boyd R (1989) What realism implies and what it does not. Dialectica 43(1/2):5–29

Boyd R (1999) Homeostasis, species, and higher Taxa. In: Wilson RA (ed) Species: new interdisciplinary essays. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, pp 141–186

Calcott B, Sterelny K (eds) (2011) The major transitions in evolution revisited. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Clarke E (2014) Origins of evolutionary transitions. J Biosci 39(2):303–317

Currie A (2019) Mass extinctions as major transitions. Biol Philos 34:29

Damuth J, Heisler IL (1988) Alternative formulations of multi-level selection. Biol Philos 3:407–430

Dawkins R (1976) The selfish gene. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Dawkins R (1982) The extended phenotype. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Dennett D (1987) The intentional stance. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Dugatkin LA, Reeve HK (1994) Behavioural ecology and levels of selection: dissolving the group selection controversy. Adv Study Behav 23:101–133

Dupre J (1981) Natural kinds and biological taxa. Philosophical Rev 90(1):66–90

Dupre J (1993) The disorder of things: metaphysical foundations for the disunity of science. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA

Godfrey-Smith P (1993) Functions: consensus without unity. Pac Philos Q 74:196–208

Godfrey-Smith P (2006) Local interaction, multilevel selection, and evolutionary transitions. Biol Theory 1(4):372–380

Godfrey-Smith P (2007) Conditions for evolution by natural selection. J Philos 104:489–516

Godfrey-Smith P (2009) Darwinian populations and natural selection. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Godfrey-Smith P, Kerr B (2002a) Individualist and multi-level perspectives on selection in structured populations. Biol Philos 17(4):477–517

Godfrey-Smith P, Kerr B (2002b) Group fitness and multi-level selection: replies to commentaries. Biol Philos 17(4):539–550

Gould SJ (2002) The structure of evolutionary theory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Grantham T (1995) Hierarchical approaches to macroevolution: recent work on species selection and the effect hypothesis. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 26:301–321

Grantham T (2007) Is macroevolution more that successive rounds of microevolution? Palaeontology 50(1):75–85

Jeler C (2020) Explanatory goals and explanatory means in multilevel selection theory. Hist Philos Life Sci 42:36

Jeler C (2021) A note against the Use of belonging to properties in multilevel selection theory. Acta Biotheor 69:377–390

Kitcher P (2003) In Mendel’s mirror: philosophical reflections on biology. Oxford University Press, New York, NY

Kitcher P (2004) Evolutionary theory and the social uses of biology. Biol Philos 19:1–15

Kitcher P, Species (1984) Philos Sci 51(2): 308–333

Kitcher P, Sterelny K, Waters CK (1990) The illusory riches of Sober’s monism. J Philos 87(3):158–161

Lewontin RC (1970) The units of selection. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 1:1–14

Lloyd EA (1988) The structure and confirmation of evolutionary theory. Greenwood, New York

Lloyd EA (2005) Why the gene will not return. Philos Sci 72(2):287–310

Lloyd EA (2017) Units and levels of selection. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. April 2017. Stanford University Centre for the study of language and information. < https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/selection-units/

Maynard Smith J (1976) Group selection. Q Rev Biology 51:277–283

Maynard Smith J (1987) How to model evolution. In: Dupre J (ed) The latest on the best: essays on evolution and optimality. MIT Press, Cambridge MA. 119–31.

Maynard Smith J, Szathmary E (1995) The major transitions in evolution. W. H. Freeman, Oxford

Michod RE (1999) Darwinian dynamics: evolutionary transitions in fitness and individuality. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ

Michod RE (2005) On the transfer of fitness from the cell to the multicellular organism. Biol Philos 20(5):967–987

Michod RE, Roze D (1999) Cooperation and conflict in the evolution of individuality III. In: Nehaniv CL (ed) Mathematical and computational biology: computational morphogenesis, hierarchical complexity, and digital evolution, vol 26. American Mathematical Society, Providence, Rhode Island, pp 47–92

Mitchell SD (1992) On pluralism and competition in evolutionary explanations. Am Zoologist Vol 32(1):135–144

Mitchell SD (2003) Biological complexity and integrative pluralism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

O’Malley M, Powell R (2016) Major problems in evolutionary transitions: how a metabolic perspective can enrich our understanding of macroevolution. Biol Philos 31:159–189

Okasha S (2006) Evolution and the levels of selection. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Kindle edition

Okasha S (2022) The major transitions in evolution—A philosophy-of-science perspective. Front Ecol Evol 10:1–10

Ryan PA, Powers ST, Watson RA (2016) Social niche construction and evolutionary transitions in individuality. Biol Philos 31:59–79

Shaw J (2016) Pluralism, pragmatism and functional explanations. Kairos: J Philos Sci 15(1):1–18

Sober E (1984) The nature of selection: evolutionary theory in philosophical focus. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Sober E (1987) Comments on Maynard Smith’s how to model evolution. In: Dupre J (ed) The latest on the best: essays on evolution and optimality. MIT Press, Cambridge MA. 133 – 45.

Sober E (2011) Did Darwin write the origin backwards? Philosophical essays on Darwin’s theory. Prometheus Books, New York. Kindle Edition

Sober E, Wilson DS (1998) Unto others: the evolution and psychology of unselfish behavior. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Sober E, Wilson DS (2002) Perspectives and parameterizations: commentary on Benjamin Kerr and Peter Godfrey-Smith’s ‘Individualist and multi-level perspectives on selection in structured populations’. Biol Philos 17(4):529–537

Sterelny K (1996) The return of the group. Philos Sci 63(4):562–584

Sterelny K, Griffiths P (1999) Sex and death: an introduction to philosophy of biology. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Sterelny K, Kitcher P (1988) The return of the gene. J Philos 85(7):335–358

Turner D (2011) Paleontology: a philosophical introduction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Vrba E (1984) What is species selection? Syst Zool 33:318–328

Vrba E (1989) Levels of selection and sorting with special reference to the species level. Oxf Surv Evolutionary Biology 6:111–168

Vrba E, Gould SJ (1986) The hierarchical expansion of sorting and selection: sorting and selection cannot be equated. Paleobiology 12(2):217–228

Waters CK (1991) Tempered realism about the forces of selection. Philos Sci 58:553–573

Waters CK (2005) Why genic and multilevel selection theories are here to stay. Philos Sci 72(2):311–333

Williams GC (1966) Adaptation and natural selection: a critique of some current evolutionary thought. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Wilson RA (2005) Genes and the agents of life: the individual in the fragile sciences, biology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Wu S, Banzhaf W (2011) Evolutionary transition through a new multilevel selection model. ECAL

Acknowledgements

Thank you to two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boucher, S.C. An argument for global realism about the units of selection. Biol Philos 38, 41 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-023-09931-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-023-09931-z