Abstract

Although prior research has documented a divergent relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision, it fails to uncover the underlying mechanisms of this relationship. Drawing from trait activation theory as the overarching theory, we develop and test a dual-path model to examine how and when leader Machiavellianism leads to abusive supervision. Specifically, we theorize leader perceived threat to hierarchy (power-threatening process) and perceived power dependence on subordinations (power-sustaining process) as two parallel mechanisms through which leader Machiavellianism affects abusive supervision. We further identify leader position power as a boundary factor that influences the power-threatening and power-sustaining processes. Using multi-wave, multi-source data collected from 175 supervisors and their 763 subordinates, we found that Machiavellian leaders were more likely to perceive high threats from subordinates to the existing hierarchy, though this threat perception was not significantly associated with abusive supervision. Additionally, Machiavellian leaders were also more likely to perceive high power dependence on subordinates, which in turn reduced their abusive supervision. We further found that leader position power strengthened the positive effect of leader Machiavellianism on leader perceived threat to hierarchy, but did not weaken the positive effect of leader Machiavellianism on leader perceived power dependence on subordinates. The implications of our findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

I’m particularly awestruck by Machiavellian business leaders—CEOs and corporate executives who are incredibly intelligent and intuitive, motivated and manipulative, diplomatic yet devious, congenial yet cunning.

– Nsehe (2011)

Introduction

Machiavellianism is characterized by people’s tendency to manipulate others for personal gains (Wilson et al., 1996). Recent years have witnessed a growing interest in examining Machiavellianism within the leadership literature (De Hoogh et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2023; Wisse & Sleebos, 2016). Leader Machiavellianism is vital to understanding leadership behaviors because it sheds light on how leaders can effectively navigate social interactions to influence their subordinates (Drory & Gluskinos, 1980; Feng et al., 2022; Kiazad et al., 2010). Moreover, contemporary business executives have advocated the application of Machiavellianism to leadership (Galie & Bopst, 2006; Spain et al., 2016) because demonstrating Machiavellianism can help them effectively attain and exercise power in organizations (Feng et al., 2022; Galie & Bopst, 2006; Jones & Paulhus, 2009). Given the theoretical and practical importance of leader Machiavellianism, understanding how leader Machiavellianism influences leaders’ behaviors can advance our understanding of Machiavellianism within the leadership literature and also inform management practices (De Hoogh et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2022).

Given that Machiavellian individuals believe in the “ends justify the means” (Jones & Paulhus, 2009), some researchers suggest that Machiavellian leaders are inclined to engage in unethical leadership behaviors such as abusive supervision—defined as “the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors towards subordinates, excluding physical contact” (Tepper, 2000, p. 178). Indeed, prior research has shown that leaders high in Machiavellianism tend to hold competitive worldview beliefs (Khan et al., 2023), demonstrate authoritarian leadership (Kiazad et al., 2010), and build close guanxi with top-level managers (Feng et al., 2022), which in turn increase their tendency to abuse subordinates to demand control over them (Feng et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2023; Kiazad et al., 2010). These findings demonstrate the cynical nature of Machiavellianism (Wilson et al., 1998) and reveal that Machiavellian leaders tend to view the world as a competitive jungle (De Hoogh et al., 2021; Wisse & Sleebos, 2016) and may perceive subordinates as a threat to their power.

While Machiavellian leaders are inclined to perceive hostile motives in subordinates and thus view their subordinates as a threat to the power hierarchy, they are also manipulative in nature by relying on their subordinates’ talents to achieve self-interests (Bereczkei, 2018; Kessler et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 1998). As subordinates’ knowledge and efforts are essential for leaders to accomplish their goals and maintain their current state of power (Overbeck, 2010), Machiavellian leaders sometimes may not abuse their subordinates as doing so prevents them from maintaining their superior hierarchical position (De Hoogh et al., 2021; Kessler et al., 2010). In this case, extant literature is characterized by conflicting findings regarding the relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision.

Although scholars have recently begun to reconcile this inconsistency (De Hoogh et al., 2021; Wisse & Sleebos, 2016), they mainly focus on examining boundary conditions (i.e., when leader Machiavellianism relates to more or less abusive supervision) rather than providing in-depth knowledge regarding the underlying mechanisms (i.e., how leader Machiavellianism relates to more or less abusive supervision). As such, we lack comprehensive knowledge about how and when leader Machiavellianism affects abusive supervision. Examining these questions is theoretically important as exploring the underlying mechanisms constitutes a principal component of theory building (Colquitt & Zapata-Phelan, 2007). Practically, a fine-grained understanding of how and when Machiavellian leaders engage in abusive supervision can provide important implications for organizations to implement interventions to reduce abusive supervision.

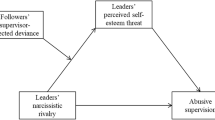

To this end, we draw from trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003) as the overarching theory to examine the power-threatening and power-sustaining processes through which leader Machiavellianism influences abusive supervision. Given the sophisticated nature of Machiavellianism (Wilson et al., 1996), we propose that Machiavellian leaders possess two competing perceptions as to whether their subordinates threaten versus sustain their power. On the one hand, Machiavellian leaders hold a cynical view of the world and show distrust towards their subordinates (Christie & Geis, 1970; Dahling et al., 2008); as such, they may see their subordinates as a threat to the existing power hierarchy—perceived threat to hierarchy, which in turn evokes their abuse towards subordinates to maintain power over them (i.e., power-threatening process). On the other hand, Machiavellian individuals possess a high degree of social intelligence, enabling them to identify and manipulate the instrumental values of others to achieve their objectives (Bereczkei, 2018; Feng et al., 2022). As such, Machiavellian leaders are more likely to recognize the significance of their subordinates’ efforts (Khan et al., 2023) and perceive more dependence on subordinates—perceived power dependence on subordinates, which in turn reduces their abuse towards subordinates to sustain their power (i.e., power-sustaining process). Taken together, we theorize leader perceived threat to hierarchy and perceived power dependence on subordinates as two competing mechanisms linking leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision.

Although we expect that Machiavellian leaders tend to hold two competing perceptions of their subordinates and subsequently engage in more or less abusive supervision, Machiavellian leaders do not always express these trait-related tendencies when interacting with subordinates. According to trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003), trait-relevant situations provide cues that elicit individuals’ different responses as specific trait propensities dictate. As the competing trait-expressed perceptions (i.e., perceived threat to hierarchy and perceived power dependence on subordinates) by Machiavellian leaders are both pertinent to their power aspirations, leader position power—defined as leaders’ formal authority to control team resources, make final decisions, and influence subordinates (Wisse & Sleebos, 2016)—conveys salient trait-relevant cues that can activate or deactivate Machiavellian leaders’ different tendencies. Specifically, because high power can lead individuals to adopt stereotypical views of others (Galinsky et al., 2008; Magee & Smith, 2013), high position power may activate Machiavellian leaders’ power-threatening process. That is, Machiavellian leaders with high position power are more likely to adopt a negative outlook towards their subordinates and thus perceive more power threats posed by subordinates, which in turn increases their abuse to maintain power over subordinates. On the other hand, high position power provides leaders with more formal authority and control over subordinates, which may reduce leaders’ motivation to identify the unique talents of their subordinates for power maintenance. As such, high position power may deactivate Machiavellian leaders’ power-sustaining process. That is, Machiavellian leaders with high position power are less likely to perceive power dependence on subordinates, which in turn increases their abuse toward subordinates. Fig. 1 depicts our theoretical model.

Overall, our research makes several theoretical contributions to the literature. First, to account for the paradoxical effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision, we examine leader perceived threat to hierarchy and power dependence on subordinates as two parallel mechanisms underlying the relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision. Doing so offers a more balanced view in understanding the effects of leader Machiavellianism. By examining the two distinct processes (i.e., leader perceived threat to hierarchy and power dependence on subordinates) through which leader Machiavellianism influences abusive supervision, our research also directly examines the duality of Machiavellian leaders. We, therefore, extend extant research that mainly examines the duality of Machiavellian leaders in an implicit way—focusing on the boundary conditions for the effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision, such as leader power (Wisse & Sleebos, 2016) and team climate (De Hoogh et al., 2021). Second, we contribute to the literature on trait activation theory by examining how individuals express their trait-related perceptual and behavioral responses when presented with trait-relevant situational cues (i.e., leader position power). Although trait activation theory has been used to relate latent traits to a variety of trait-related behavioral responses (Tett et al., 2021), little research considers individuals’ other trait-related responses (e.g., perceptions) that can play a key role in translating latent traits into observable behaviors (Barrick & Mount, 2005). We thus extend trait activation theory by demonstrating that the activation of Machiavellianism can impact Machiavellian leaders’ different perceptions of their subordinates (i.e., leader perceived threat to hierarchy and power dependence on subordinates), which in turn influence their behavior towards subordinates (i.e., abusive supervision).

Third, by examining leader position power as a boundary factor in shaping how leader Machiavellianism influences abusive supervision through the power-threatening and power-sustaining processes, we answer the recent call for examining key situational factors that may moderate the relationship between Machiavellianism and anti-social behavior (Monaghan et al., 2020). Finally, our study contributes to the power literature by uncovering the bi-directional nature of power (Keltner et al., 2008). Although leaders are usually considered more powerful than subordinates, power actually operates through a bi-directional process whereby subordinates depend on leaders to acquire valued resources and leaders also depend on subordinates to maintain power and exert influence (Keltner et al., 2008; Overbeck, 2010). Our power-sustaining process reveals that Machiavellian leaders need to depend on subordinates to achieve goals—leader perceived power dependence on subordinates, which is undertheorized in prior research.

Theory and hypotheses

Leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision

Machiavellianism was introduced by Niccolò Machiavelli (1513/1998) to describe political leaders’ use of deceitful and manipulative strategies to gain power and control (Machiavelli, 1513/1998). Christie and Geis (1970) further conceptualize Machiavellianism as a personality trait that refers to the dispositional tendency to manipulate others for one’s own benefit. Machiavellian individuals tend to hold a cynical worldview that people are naturally self-serving and untrustworthy, have a strong desire to maintain dominance over interpersonal situations and achieve high status in social settings, and exhibit adaptiveness in monitoring and manipulating social environments for personal gain (Dahling et al., 2008). These characteristics can help Machiavellian individuals survive in a competitive environment and climb to leadership positions (Jones & Paulhus, 2009; Wisse & Sleebos, 2016). However, once Machiavellian individuals are promoted to team leaders, they may manage their team in an impersonal way and abuse their subordinates to command compliance (Jones & Paulhus, 2009; Kiazad et al., 2010).

Over the last decade, researchers have sought to understand the relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision. Focusing on Machiavellianism’s cynical nature and distrust of others (Dahling et al., 2008), prior studies have found that leader Machiavellianism is positively related to abusive supervision. For example, Kiazad et al. (2010) demonstrated that Machiavellian leaders tend to exhibit authoritarian leadership, which in turn increases their abusive supervision to demand unquestionable obedience from subordinates. Khan et al. (2023) showed that Machiavellian leaders are more likely to adopt competitive worldview beliefs that people in the world compete against each other, which in turn evokes their abusive behaviors toward their subordinates. Feng et al. (2022) found that Machiavellian leaders can effectively implement abusive supervision to reinforce control over subordinates through developing close guanxi with their top-level managers. Results from these studies suggest that Machiavellian leaders may view their subordinates as potential power threats, thereby increasing their abusive supervision to eliminate these power threats.

The complexity of Machiavellian leaders

While prior research shows a positive relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision (e.g., Kiazad et al., 2010), extant literature also points to the possibility that leader Machiavellianism may reduce abusive supervision. According to Machiavellianism literature (Monaghan et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 1996), Machiavellian individuals are good at examining situations to determine the appropriate approach to manipulate the environment effectively and maintain their position in social groups. On the one hand, they may perceive others as threatening who intend to compete for scarce resources (e.g., power and status), which stimulates them to undermine other members’ control over the group (Dahling et al., 2008; Wilson et al., 1998). On the other hand, they may see other people as useful resources to enhance their power. As such, they tend to withdraw their anti-social behaviors (Wilson et al., 1996, 1998).

For Machiavellian leaders, although they are likely to see subordinates as untrustworthy and power-threatening (Feng et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2023), they also need subordinates’ resources and support to maintain their power and leadership position. The effective exercise of leadership requires leaders to attend to the task-related skills of their subordinates and coordinate subordinates’ efforts to achieve team goals (Lee & Tiedens, 2001; Overbeck, 2010). Therefore, Machiavellian leaders with a high degree of social intelligence will recognize their subordinates’ essential role in maintaining their power and thus may not engage in abusive supervision toward their subordinates (Khan et al., 2023). Indeed, research hints that leader Machiavellianism may not always increase abusive supervision and instead could reduce abusive supervision. For instance, Deluga (2001) notes that Machiavellian leaders are motivated to portray a desired image to attract their subordinates’ loyalty and support. Furthermore, Khan et al. (2023) suggest that Machiavellian leaders may perceive their subordinates (especially high performers) as important resources to promote their success in the organization. This evidence points to the possibility that leader Machiavellianism may negatively relate to abusive supervision. Therefore, the effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision could be mixed, which may explain why a recent meta-analysis fails to find a significant positive relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision (Zhang & Bednall, 2016).

Considering the mixed effects of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision, researchers have recently begun to investigate the boundary conditions that determine when Machiavellian leaders abuse their subordinates. Research has shown that leader position power (Wisse & Sleebos, 2016), employee performance (Khan et al., 2023), and psychological work climate (De Hoogh et al., 2021) can shape the effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision. Though insightful, these studies provide a limited understanding of the mechanisms through which leader Machiavellianism may influence abusive supervision in either a positive or negative way. To uncover the complex influence of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision, we draw from trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003) as the overarching theory to examine how and when leader Machiavellianism influences abusive supervision through both the power-threatening and the power-sustaining processes.

The power-threatening process: the mediating role of perceived threat to hierarchy

According to Machiavellianism literature (Dahling et al., 2008; Wilson et al., 1996), Machiavellian people hold the belief that individuals are inherently untrustworthy and vulnerable to be exploited (Fehr et al., 1992; McIlwain, 2003); they regard the world as unjust and believe that individuals are always looking for opportunities to interfere with others’ power and status (Monaghan et al., 2020). Therefore, individuals high in Machiavellianism have a negative view toward others and tend to take aggressive actions to defend their power and position (Dahling et al., 2008; Geis & Moon, 1981). Building on the cynical and distrusting worldview of Machiavellian people (Dahling et al., 2008; Geis & Moon, 1981), we propose that leaders high in Machiavellianism tend to perceive a high threat from subordinates to the existing power hierarchy, which in turn triggers abusive supervision.

Perceived threat to hierarchy is defined as leaders’ perception that their power hierarchy is challenged by their subordinates (Khan et al., 2018). This power threat perception does not necessarily derive from the actual fact that subordinates are threatening their leaders’ power and status in the organization. Rather, leaders may perceive a high power threat to the existing hierarchy when they feel that subordinates have the intention or opportunity to undermine their control over the team (Davis & Stephan, 2011). One of the core characteristics of Machiavellians is showing distrust in others (Dahling et al., 2008). Therefore, leaders high in Machiavellianism are more inclined to have a cynical outlook toward their subordinates’ intentions and perceive that their subordinates are opportunistic. That is, Machiavellian leaders tend to view their subordinates as not genuinely complying with the organization’s hierarchy and preparing themselves to take over leadership positions in the future. As such, Machiavellian leaders may view their subordinates as potential threateners who contend for power and resources. In addition, the power and authority associated with leadership positions enlarge the social distance between leaders and subordinates (Magee & Smith, 2013). This enlarged social distance reinforces the notion that leaders and subordinates belong to different spheres, which may prompt Machiavellian leaders to stereotype others and show distrusting tendencies toward subordinates. Providing support for our arguments, Khan et al. (2023) found that Machiavellian leaders tend to adopt a competitive worldview that people compete with each other for survival. Therefore, Machiavellian leaders are more likely to perceive high threats from subordinates to the existing hierarchy compared to non-Machiavellian counterparts.

In response to this power threat posed by subordinates, Machiavellian leaders engage in abusive supervision so as to maintain their power over subordinates. Research on abusive supervision suggests that leaders may strategically use abusive supervision to eliminate threats and strengthen their power (Tepper et al., 2012). By abusing their subordinates, leaders can put subordinates in a weak and helpless position, thereby reinforcing their power and status (Ferris et al., 2007). Moreover, abusive supervision can force compliance from subordinates and therefore enhance leaders’ image as a figure of authority (Tepper et al., 2011). As such, through abusing their subordinates, Machiavellian leaders can reinforce their position in the organizational power hierarchy and execute their domination over subordinates. Supporting our arguments, prior research found a positive relationship between leaders’ perceived threat to hierarchy and abusive supervision (Khan et al., 2018). Taking these arguments together, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1

Leader perceived threat to hierarchy mediates the positive relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision.

The power-sustaining process: the mediating role of perceived power dependence on subordinates

Although subordinates may be viewed by Machiavellian leaders as potential power threats and consequently arouse their abusive reactions, subordinates play an essential role in Machiavellian leaders’ goal achievement process. While subordinates need to rely on leaders to acquire valuable resources and rewards, leaders also rely on the efforts and resources of subordinates to exert their leadership roles and maintain their position (Uhl-Bien et al., 2014). This is because, without the support of subordinates, leaders do not have the capacity to act and maintain their current state of power (Overbeck, 2010). As such, compared to non-Machiavellian leaders, Machiavellian leaders are more likely to realize the importance of subordinates in sustaining their power because they are goal-oriented and have a high degree of social intelligence to identify others’ instrumental values (Deluga, 2001; Kiazad et al., 2010). Therefore, we predict that Machiavellian leaders are more likely to perceive high power dependence on their subordinates, which in turn reduces abusive supervision.

Perceived power dependence on subordinates refers to leaders’ perception of the degree to which they need information, resources, or knowledge from subordinates to achieve valued goals (Wee et al., 2017). Prior research shows that leaders are more likely to perceive high power dependence on subordinates when their subordinates hold instrumental values such as work skills or resources that they regard as important (Gargiulo & Ertug, 2014; Murray et al., 2009). For Machiavellian leaders, they have a strong desire for power and status (Dahling et al., 2008; Deluga, 2001). Therefore, their primary goal is to maintain high power and status in the organization (Christie & Geis, 1970; Kiazad et al., 2010). As maintaining a leadership position is closely related to subordinates’ work efforts (Uhl-Bien et al., 2014), Machiavellian leaders may feel a need to rely on their subordinates to achieve their goals. More importantly, Machiavellians have high social intelligence—they can understand social dynamics and figure out the strengths and weaknesses of the social environment (Bereczkei, 2018; Wilson et al., 1996). Considering this, Machiavellian leaders with exceptional cognitive skills can figure out the interdependent nature of the leader-follower relationship and identify their subordinates’ instrumental value in relation to their goals. In other words, compared to non-Machiavellian leaders, Machiavellian leaders develop a better understanding of their subordinates’ talents and are more aware of the essential role of subordinates in sustaining their power. Additionally, leadership positions cause an asymmetrical dependence between leaders and subordinates and offer leaders a chance to exploit their subordinates for the sake of achieving their goals (Farmer & Aguinis, 2005). The opportunities for Machiavellian leaders to leverage their subordinates for goal pursuit may encourage Machiavellian leaders to see their subordinates as valuable resources that can be harnessed to accomplish their goals. Therefore, Machiavellian leaders are more likely to perceive high power dependence on subordinates compared to non-Machiavellian counterparts.

Perceived power dependence on subordinates will, in turn, reduce Machiavellian leaders’ tendency to engage in abusive supervision. Research on abusive supervision has shown that abusive supervision has negative implications for employees’ work efforts and performance (Tepper et al., 2017); it may even arouse subordinates’ retaliation such as withholding work-related information or ignoring leaders’ requests (Harvey et al., 2014). As these negative consequences lead to Machiavellian leaders’ power dependence on subordinates less possible, Machiavellian leaders who perceive high power dependence on subordinates will reduce their abuse toward subordinates. Supporting this notion, Wee et al. (2017) found that leaders’ power dependence on subordinates decreases their abusive supervision toward subordinates. Taking these arguments together, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2

Leader perceived power dependence on subordinates mediates the negative relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision.

The trait activation Lens: the moderating role of leader position power

So far, we have discussed the two competing power processes (i.e., power-threatening process and power-sustaining process) to explain the mixed relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision. However, according to trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003; Tett et al., 2013), the activation of these two power processes predicted by Machiavellian propensities depends on certain situations. The key tenet of trait activation theory is that the situations trigger personality traits that reside in the individual, which prompts individuals to engage in trait-related expressions (Tett & Burnett, 2003). Individuals possess stable and enduring traits that influence their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Tett & Guterman, 2000). However, individuals do not necessarily express their personality traits in all situations. The expression of a certain trait is activated when individuals perceive that the situations favor them to engage in such expression (Tett & Guterman, 2000). Although trait activation theory primarily focuses on trait expression in terms of observable behaviors (Tett & Burnett, 2003), the manifestation of traits in distal behaviors is usually transmitted by more proximal cognitions (Barrick & Mount, 2005). Recent research that utilizes trait activation theory also indicates that trait-relevant situations may arouse individuals’ trait-related affective, cognitive, and behavioral expressions (Dust et al., 2022; Watson et al., 2013).

Applying the tenet of trait activation theory to Machiavellian leaders, we propose that the activation or deactivation of Machiavellian leaders’ power-threatening and power-sustaining processes is contingent upon their position power. Leader position power refers to the degree to which leaders have the authority to control valued resources (e.g., reward or punishment) and influence their subordinates (Wisse & Sleebos, 2016), which aligns closely with the core motivations and inclinations of Machiavellian individuals (e.g., showing a strong desire for power and control and seeking to manipulate and exploit others to serve their own interests; Dahling et al., 2008). Due to this alignment, leader position power can provide salient Machiavellianism-related cues that may amplify or mitigate Machiavellian leaders’ different propensities of attaining and maintaining power. Consistent with this notion, Machiavellianism literature also suggests that Machiavellian individuals tend to leverage their Machiavellian characteristics when it benefits their pursuit of power (Dahling et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2022; Wilson et al., 1998).

We first predict that position power will activate Machiavellian leaders’ power-threatening process. High power increases powerful people’s perceived social distance from their powerless counterparts (Magee & Smith, 2013), such that Machiavellian leaders with high position power view themselves as independent and separate from their subordinates. This separateness may trigger Machiavellian leaders’ inclination to apply stereotypes when interacting with their subordinates. Indeed, because of Machiavellianism’s core characteristic of distrust in others (Dahling et al., 2008), high position power can activate Machiavellian leaders’ distrusting view of subordinates that their subordinates are self-interested and dare to challenge leaders’ authority once they appear incompetent. In other words, when position power is high, Machiavellian leaders are more likely to adopt a negative outlook toward their subordinates and view subordinates as potential competitors who may threaten their power.

Additionally, high position power will direct the attention of Machiavellian leaders toward the possibility of power loss, which may further activate their distrust in subordinates. Research suggests that high position power can enhance leaders’ fear of losing power (Anderson & Brion, 2014) and heighten their vigilance about the possibility of power loss. Empirical evidence has also shown that, when occupying high power positions, people with a strong desire for power tend to be afraid of losing power and pay much attention to potential threats (Maner et al., 2007; Mooijman et al., 2015). Considering the Machiavellians’ strong desire for power and control (Dahling et al., 2008), high position power can increase Machiavellian leaders’ sensitivity to potential threats from their subordinates. As such, Machiavellian leaders with high position power are more likely to express their distrust in subordinates. Therefore, when position power is high, Machiavellian leaders are more likely to perceive high threats from their subordinates to the power hierarchy, which leads to abusive supervision. Based on these arguments, we propose that leader position power strengthens the indirect effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision via leader perceived threat to hierarchy:

Hypothesis 3

Leader position power moderates the indirect effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision via leader perceived threat to hierarchy, such that this indirect effect is stronger when leader position power is high than when it is low.

By contrast, we propose that position power will deactivate Machiavellian leaders’ power-sustaining process. High position power reduces the necessity of Machiavellian leaders to rely on subordinates to acquire power and status, which may inhibit their propensities to rely on subordinates for power maintenance. More specifically, power can promote people’s self-view and control over social situations (Magee & Smith, 2013). When position power is high, Machiavellian leaders can leverage their formal authority to exert dominance and control over subordinates; they can also elicit desired behaviors and discourage unwanted behaviors by implementing formal rewards or punishments. In this case, high position power provides alternative ways for Machiavellian leaders to maintain power, which may reduce their tendencies to utilize subordinates for power maintenance. As such, Machiavellian leaders with high position power are less likely to perceive power dependence on subordinates and consequently enhance abusive supervision.

Additionally, high position power may suppress Machiavellian leaders’ inclination to identify subordinates’ capability and reduce their perceptions of the instrumental value of subordinates. Research indicates that power increases individuals’ capacity to construe targets at a higher level (Magee & Smith, 2013) and their tendency to engage in abstract processing of information (Smith & Trope, 2006). The great abstraction in cognitive processing causes powerful people to dismiss the perspectives and abilities of people around them (Magee & Smith, 2013). Indeed, prior research suggests that powerholders take a dehumanizing view of others, that is, they ignore individuals’ unique needs and characteristics (Schroeder & Epley, 2020). In this case, Machiavellian leaders with high position power are less likely to exhibit their social intelligence and identify subordinates’ talents. Therefore, when position power is high, Machiavellian leaders are less likely to perceive dependence on subordinates for power maintenance, which increases their abusive supervision towards subordinates. Taking these arguments together, we propose that leader position power attenuates the indirect effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision via leader perceived power dependence on subordinates:

Hypothesis 4

Leader position power moderates the indirect effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision via leader perceived power dependence on subordinates, such that this indirect effect is weaker when leader position power is high than when it is low.

Methods

Sample and procedure

Our data was collected from part-time Master of Business Administration (MBA) students enrolled in a large university in eastern China. These MBA students had full-time jobs across diverse industries, including manufacturing, technology, commerce, and architecture, which ensures the generalizability of our findings. They all held leadership positions (i.e., serving as a supervisor) and had subordinates who directly reported to them. A total of 204 leaders (MBA students) and their 885 subordinates agreed to participate in our study and constituted our initial sample.

We conducted three-round surveys of different sources (i.e., leaders and subordinates) with approximately two-week intervals between each round. At Time 1, we distributed online questionnaires to leaders. Leaders were asked to report their demographic information and rate their personalities in terms of Machiavellianism. 200 complete questionnaires from leaders were received, yielding a response rate of 98.04%. At Time 2, we distributed online questionnaires to leaders and asked them to assess their position power, perceived threat to hierarchy, and perceived power dependence on subordinates. 199 complete questionnaires from leaders were received, yielding a response rate of 99.50%. At Time 3, we distributed online questionnaires to subordinates under the direct supervision of the leaders. Subordinates were asked to report their demographic information and provide ratings of their perceived abusive supervision. 800 complete questionnaires from subordinates who directly reported to their 188 leaders were received, yielding a response rate of 94.47%.

In the final leader sample, 66.8% were men, the average age was 33.4 years, and the average team tenure was 4.48 years. In the final subordinate sample, 53.09% were men, the average age was 31.2 years, and the average team tenure was 4.23 years. The team size (including team leaders) ranged from 3 to 19 with an average team size of 4.76.

Measures

All surveys that were originally developed in English were translated into Chinese following the back-translation method (Brislin, 1986). All ratings were made on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) unless otherwise indicated below. Full measures are provided in Appendix.

Leader Machiavellianism (Time 1; leader-rated)

Team leaders were asked to report their Machiavellianism on a 16-item Machiavellianism Personality Scale (MPS) developed by Dahling et al. (2008). This scale contains four dimensions (i.e., distrust of others, desire for control, desire for status, and amoral manipulation) with five items for distrust of others (e.g., “I dislike committing to groups because I don’t trust others”), three items for desire for control (e.g., “I enjoy being able to control the situation”), three items for desire for status (e.g., “Status is a good sign of success in life”), and five items for amoral manipulation (e.g., “The only good reason to talk to others is to get information that I can use to my benefit”) (α = 0.91).

Leader position power (Time 2; leader-rated)

We measured leader position power using six items developed by Wisse and Sleebos (2016). The original scale contains seven items. One item (i.e., “I take part in all the important advisory boards/committees”) was not suitable for our sample because most team leaders in this study held a relatively lower rank in the organization and did not engage in boards or committees, so this item was deleted. A sample item was “I have the authority to fire my subordinates” on a 5-point Likert Scale anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (α = 0.88).

Perceived threat to hierarchy (Time 2; leader-rated)

We used the 3-item scale developed by Khan et al. (2018) to measure leaders’ perceived threat to hierarchy. A sample item was “I feel a threat to the existing hierarchy by my subordinates” (α = 0.89).

Perceived power dependence on subordinates (Time 2; leader-rated)

We measured leaders’ perceived power dependence on subordinates using Wee et al.’s (2017) 6-item scale. This scale was originally used to measure team leaders’ perception of dependence on one specific subordinate to achieve their valued goals and resources, which was an individual-level construct (Wee et al., 2017). However, based on our research, we made a reference shift and changed the focus from one specific team member to team members as a whole. A sample item was “How reliant are you on your subordinates for career goals that you care about?” (α = 0.95).

Abusive supervision (Time 3; subordinate-rated)

We asked team members to rate abusive supervision using the 15-item scale developed by Tepper (2000). A sample item was “My boss ridicules me” (α = 0.98). We aggregated each team member’s rating of abusive supervision to the team level and treated it as a team-level construct (Chan, 1998). To examine the appropriateness of aggregating abusive supervision at the team level, we calculated within-group interrater reliability using the within-group interrater agreement measure (i.e., Rwg) and the intra-class correlation (ICC) coefficients (Bliese, 2000; James et al., 1984). We followed James et al.’s (1984) method to calculate Rwg(j) and identified 13 teams with negative Rwg(j) values. Negative Rwg(j) values may indicate low within-team agreement in perceptions of abusive supervision among team members (LeBreton & Senter, 2008). To ensure construct validity (Klein et al., 2001), we dropped these 13 teams, yielding the final sample of 175 teams for subsequent hypotheses testing. The Rwg(j) value ranged from 0.36 to 1.00, with a mean of 0.98. The intra-class correlation values were 0.20 (ICC(1) and 0.52 (ICC(2), respectively. The ICC(1) value was greater than the recommended value of 0.059 (Cohen, 1988), which indicated high agreement on experienced abusive supervision among team members within a team. The ICC(2) value was relatively low, which can be explained by the relatively small number of responses per group (average = 4.36; Bliese, 2000). However, the aggregation of abusive supervision is still appropriate, as abusive supervision can be theoretically examined as a group-level construct (e.g., Liu et al., 2012), and other within-group agreement indices (e.g., high Rwg(j) and ICC(1) values) also support the appropriateness of aggregation (Chen & Bliese, 2002).

Control variables

Following prior practices (Belschak et al., 2013), we controlled for leader age, gender, and team tenure, which may influence abusive supervision and bias our results. Gender was coded “0” for female and “1” for male. Team tenure was measured by the number of years.

Analytical strategy

Before testing hypotheses, we followed Cheung et al.’s (2023) approach to use the measureQ package in R to examine our measurement models and evaluate the discriminatory validity of our measures.

We first conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to estimate our measurement models. Due to the different sample sizes, we conducted CFAs for the leader and subordinate samples, respectively. For the CFA of the leader sample (which contained variables including leader Machiavellianism, leader position power, leader perceived threat to hierarchy, and leader perceived power dependence on subordinates), we used the item parceling method to create factors for our focal variables with more than three items because the item-to-sample size ratio of 31:175 is lower than the recommended values (i.e., 1:10; Garson, 2008; Kunce et al., 1975; Marascuilo & Levin, 1983). Item parceling is a preferred method when the sample size is small. This is because CFAs are highly sensitive to sample size and low sample size may cause instability of the factor solution (Little et al., 2002; Marsh & Hocevar, 1988). As leader Machiavellianism contains four dimensions (i.e., distrust of others, desire for status, desire for control, and amoral manipulation), we followed prior research (Chen et al., 2007) to create four parcels by averaging scores on each dimension of Machiavellianism as the indicators of leader Machiavellianism. For other variables with more than three items and without sub-dimensions (i.e., leader position power and leader perceived power dependence on subordinates), we used the item-to-construct balance approach (Little et al., 2002) to create three parcels of items as indicators for each latent variable by averaging the highest factor loading items with the lowest factor loading items. Therefore, leader position power and leader perceived power dependence on subordinates were all represented by three parcels of items.

After examining the discriminant validity of our measures, we used Mplus 7.4 to conduct linear regression analyses to test our hypotheses. For mediation effects, we used bootstrapping with 20,000 resamples to generate the confidence intervals of the indirect effects (Preacher & Selig, 2012). The indirect effect receives support when the confidence interval excludes zero. In addition, for moderation terms (i.e., leader Machiavellianism and leader position power), we grand-mean centered relevant variables to reduce the possible multicollinearity (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

The CFA results for the leader sample showed that the four-factor model (i.e., leader Machiavellianism, leader position power, leader perceived threat to hierarchy, and leader perceived power dependence on subordinates) fit the data well (χ2(59) = 94.56, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.06) and was better than all alternative models. Because there was only one variable (i.e., abusive supervision) in the subordinate sample, we conducted a one-factor model CFA. Results indicated an adequate fit to the data (χ2(90) = 1383.53, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.90, SRMR = 0.03, RMSEA = 0.14). In addition to these model fit indexes, we also calculated additional criteria to guarantee our measurement quality, including factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) values. The standardized factor loadings for each construct were greater than the 0.50 criterion (Hair et al., 2009). All scores of CR were greater than the recommended value of 0.70 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) and the AVE values were greater than the recommended value of 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2009). These results demonstrated an acceptable level of discriminant validity of our measures (Fornell, & Larcker, 1981)Footnote 1.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations of all variables.

Hypothesis 1 predicted that leader perceived threat to hierarchy mediates the positive relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision. The regression results of Model 1 and Model 6 in Table 2 indicated that leader Machiavellianism was significantly and positively related to leader perceived threat to hierarchy (b = 0.30, SE = 0.09, p = .001). However, leader perceived threat to hierarchy was not significantly related to abusive supervision (b = 0.06, SE = 0.05, p = .206). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was not supported.

Hypothesis 2 proposed that leader perceived power dependence on subordinates mediates the negative relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision. According to Model 3 and Model 6 in Table 2, leader Machiavellianism positively predicted perceived power dependence on subordinates (b = 0.23, SE = 0.11, p = .034), and leader power dependence on subordinates negatively predicted abusive supervision (b = − 0.13, SE = 0.04, p < .001). The indirect effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision through perceived dependence on subordinates was also significant (indirect effect = − 0.031, 95% CI = − 0.069, − 0.002), thus providing support for Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3 stated that the indirect effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision via leader perceived threat to hierarchy will become stronger when leader position power is high rather than low. The results of Model 2 in Table 2 revealed that the moderation term of leader Machiavellianism and position power was significantly and positively related to leader perceived threat to hierarchy (b = 0.21, SE = 0.09, p = .014). Simple slope tests suggested that the effect of leader Machiavellianism on perceived threat to hierarchy was significant for leaders with high position power (b = 0.50, p < .001) but not for leaders with low position power (b = 0.12, p = .212). The difference in the effect of leader Machiavellianism on perceived threat to hierarchy between high and low groups of position power was significant (difference = 0.38, p = .005). Fig. 2 shows this first-stage moderating effect of leader position power on the relationship between leader Machiavellianism and leader perceived threat to hierarchy. However, because the relationship between leader perceived threat to hierarchy and abusive supervision was not significant, the moderating effect of leader position power on the indirect relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision via leader perceived threat to hierarchy (Hypothesis 3) was not supported.

Hypothesis 4 predicted that leader position power moderates the indirect effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision via leader perceived power dependence on subordinates, such that this indirect effect becomes weaker when leader position power is high rather than low. Inconsistent with our prediction, the results of Model 4 in Table 2 showed that the moderation term of leader Machiavellianism and position power was not significantly related to leader perceived power dependence on subordinates (b = 0.08, SE = 0.11, p = .468). As the first-stage moderation effect was not significant, the moderated mediation hypothesis (Hypothesis 4) was not supported.

Discussion

Drawing from trait activation theory (Tett & Burnett, 2003) as the overarching theory, our research seeks to advance theoretical understanding of the mixed effects of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision. Our findings showed that Machiavellian leaders not only perceived high threats from subordinates to the existing hierarchy, but also perceived high power dependence on subordinates. While perceived high threat to hierarchy did not affect abusive supervision, perceived high power dependence on subordinates reduced abusive supervision. Moreover, we found that when leader position power was high, the positive relationship between leader Machiavellianism and leader perceived threat to hierarchy was stronger. These findings provide important theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical implications

Our research draws from trait activation theory as the overarching theory to elucidate the psychological mechanisms underlying how and when leader Machiavellianism can increase or decrease abusive supervision, thus answering research calls for addressing the complex effects of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision (De Hoogh et al., 2021; Tepper et al., 2017; Zhang & Bednall, 2016). Although prior studies mainly hold that Machiavellian leaders prefer aggression and abuse toward their subordinates (e.g., Kiazad et al., 2010; Wisse & Sleebos, 2016), many researchers argue that it is too early to jump to the conclusion that leader Machiavellianism is positively related to abusive supervision (De Hoogh et al., 2021). Indeed, both theoretical and practical inferences indicate a potential negative influence of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision (Dahling et al., 2008; Kiazad et al., 2010). However, prior work has mainly focused on the positive relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision. Our research advances extant literature by unpacking leader perceived threat to hierarchy (a power-threatening process) and perceived power dependence on subordinates (a power-sustaining process) as two parallel mechanisms explaining the mixed effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision.

Specifically, regarding the power-threatening process, our findings echo prior research (De Hoogh et al., 2021; Kiazad et al., 2010), demonstrating that Machiavellian leaders often possess a cynical worldview and may perceive their subordinates as potential threats who compete for power. Of note, we did not find an association between leader perceived threat to hierarchy and abusive supervision. This unexpected result may be accounted for by different strategies that Machiavellian leaders choose to manage threats from their social environment (Mead & Maner, 2012). In response to subordinates who may threaten their power, leaders do not necessarily engage in abusive supervision to undermine subordinates’ influence and thus maintain control. Rather, leaders may seek closeness with those subordinates to better control threats and protect their power (Mead & Maner, 2012). Therefore, the relationship between leader perceived threat to hierarchy and abusive supervision may be more complex than currently theorized. Regarding the power-sustaining process, our findings offer critical insights that Machiavellian leaders possess high social intelligence and can identify their subordinates’ instrumental value for power maintenance, which reduces their tendency to engage in abusive supervision. To our knowledge, our work is among the first to document that leader Machiavellianism can diminish abusive supervision via leader perceived power dependence on subordinates. Therefore, our study sheds new light on the relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision.

Second, by simultaneously investigating the power-threatening and power-sustaining processes, our research provides direct examinations of the complexity of Machiavellian leaders. Machiavellianism literature has suggested that Machiavellians are adaptive to utilizing the environment for their own benefit and may hold different mindsets to deal with their interpersonal interactions (Monaghan et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 1996, 1998). Our research extends this line of research by drawing from trait activation theory to uncover the competing perceptions of Machiavellian leaders toward their subordinates. We theorize that Machiavellian leaders tend to hold two competing perceptions of their subordinates as indicated by the complexity of Machiavellianism. On the one hand, because of the cynical nature of Machiavellian personality, Machiavellian leaders tend to distrust others and may consider their subordinates as competitors who have the possibility to threaten their power. Therefore, they are inclined to perceive their subordinates as a threat. On the other hand, teams and organizations are established in collaborative settings (Tost & Johnson, 2019) in which leaders and subordinates who are assigned different roles need to cooperate with each other to achieve group goals as well as personal goals (Blau, 1964). In this case, Machiavellian leaders, who have high social intelligence (Bereczkei, 2018), understand that they should depend on their subordinates to achieve status and other benefits. Therefore, they are also inclined to perceive high power dependence on their subordinates. By integrating these two competing mechanisms, our work highlights the complex and adaptive nature of Machiavellian leaders, which lays the groundwork for future research to put forth a holistic model when investigating the impact of leader Machiavellianism.

Third, our study sheds light on trait activation theory by enriching the trait-related responses expressed by individuals when they are presented with trait-relevant situational cues. Trait activation theory posits that individuals tend to express a specific trait when they encounter situations relevant to this trait (Tett & Burnett, 2003). The trait expression is usually examined in the form of behavioral expressions (Tett et al., 2021). Although the manifestation of traits in distal behaviors is often mediated by more proximal cognitions (Barrick & Mount, 2005), prior research utilizing trait activation theory fails to consider how traits manifest in cognitive expressions. This omission is particularly consequential when considering the complexity of certain personalities, such as Machiavellianism. Machiavellian individuals are flexible in their use of the environment to benefit themselves and thus can express different propensities to navigate their interpersonal interactions (Monaghan et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 1996, 1998). So, under trait-related conditions (e.g., high leader position power), different trait-related cognitions may emerge to translate the Machiavellian personality to distal behaviors. By broadening the scope of trait activation theory, our research shows that the activation of Machiavellianism manifests in leaders’ two competing perceptions of subordinates (i.e., perceived threat to hierarchy and power dependence on subordinates). In doing so, our research highlights the important role of trait activation in not only shaping overt behaviors but also influencing cognitive and perceptual processes in individuals.

Fourth, our study draws from the trait activation theory to identify one key situational factor—leader position power—that provides salient trait-related cues activating or deactivating Machiavellian trait expressions (i.e., power-threatening and power-sustaining processes). Our study found that high position power strengthens Machiavellian leaders’ perceived threat to hierarchy. This result echoes power literature which depicts how “power reveals the person” (Hirsh et al., 2011, p. 418). The psychology of power posits that powerholders tend to act in accordance with their internal states such as their emotions and personality (Galinsky et al., 2008). Providing support for this argument, we found that high position power may stimulate Machiavellian leaders to manifest their cynical worldviews and perceive others as untrustworthy, competitors, and manipulative objects. As such, they are more likely to perceive a high threat from subordinates to the existing hierarchy when their position power is high. Therefore, our study incorporates the Machiavellian personality to advance our understanding of how power elicits individuals’ expression of trait-related responses.

Unexpectedly, we failed to find the moderating effect of leader position power on the power-sustaining process underlying the negative relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision via leader perceived power dependence on subordinates. Our results showed that no matter whether Machiavellian leaders have high or low position power, they may always perceive high power dependence on subordinates. A plausible explanation for this finding is that high position power does not necessarily mean that leaders can exert their own will and are free from subordinates’ influence (Heller et al., 2023; Tost, 2015). Although leaders with high position power can command control and dominance by resorting to their hierarchical position and implementing formal rewards and punishments, their exercise of power and influence may not be effective without the support of subordinates (Tost, 2015). Therefore, Machiavellian leaders who are sensitive to the nature of social situations should realize that regardless of whether they have high or low position power, they still need subordinates’ conformity to their influence so as to maintain power.

Finally, our power-sustaining process (i.e., leader perceived power dependence on subordinates) also contributes to the power literature by uncovering the interdependence nature in leader-subordinate interaction. Although power researchers argue that powerful people are not entirely free and may be affected by their subordinates (Tost, 2015), power literature has predominantly focused on how powerholders treat their subordinates and impact subordinates’ behaviors (Galinsky et al., 2008). Recent research has called for a more balanced view by examining the bi-directional nature of power (Keltner et al., 2008; Tost & Johnson, 2019). Followership scholars also highlight the important role of subordinates in shaping their leaders’ influence and power (Oc & Bashshur, 2013). Answering this call, our research provides evidence that Machiavellian leaders can identify the value of subordinates in sustaining their power (i.e., perceiving high power dependence on subordinates). As such, our findings lend support to the notion that power operates in a mutual-dependence process in which leaders and subordinates rely on each other.

Practical implications

Our research has clear and immediate implications for managerial practice. First, our findings showed that Machiavellian leaders perceived a high level of dependence on subordinates for power, which in turn reduced abusive supervision. This finding implies that organizations can take some measures to reduce Machiavellian leaders’ abusive behaviors. For example, organizations can enhance Machiavellian leaders’ perceived power dependence on subordinates by establishing a close connection between the performance of Machiavellian leaders and that of subordinates. By linking the achievements and successes of Machiavellian leaders with the overall performance of subordinates, organizations can reinforce the notion to Machiavellian leaders that they rely on their subordinates for achieving success, which would reduce their tendency to abuse their subordinates (Wee et al., 2017).

In addition, building upon the trait activation theory, we demonstrate that the influence of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision is not inherent but rather activated by power-related stimuli. Specifically, we found that Machiavellian leaders were more likely to perceive high threats from subordinates to the existing hierarchy when their position power was high. This is because high position power allows Machiavellian leaders to freely express their traits and thus might trigger their distrust in subordinates (Wisse & Sleebos, 2016); as such, Machiavellian leaders are more likely to perceive threats from their subordinates to the existing power hierarchy. Therefore, it is recommended for organizations to proactively create a conducive work environment, wherein the undesirable aspects of Machiavellian leaders (i.e., perceived threat to hierarchy) are less likely to be activated. For example, organizations can alleviate Machiavellian leaders’ perception of power threats from subordinates by reducing the level of organizational politics. In an organizational setting with low levels of politics, there are fewer hidden agendas and power struggles, which allows for more open communication and collaboration between leaders and subordinates (Cheng et al., 2022). This open and supportive work environment can help Machiavellian leaders see their team in a more positive light and thus reduce their perception of threats from subordinates.

Another implication of our study relates to how subordinates can interact with Machiavellian leaders and avoid being abused. Considering the two competing perceptions that Machiavellian leaders hold toward subordinates, subordinates can adopt two courses of action to promote their interactions with Machiavellian leaders—reducing leader perceived threat to hierarchy and increasing leader perceived power dependence on subordinates. On the one hand, subordinates can show benevolence or build high-quality relationships with Machiavellian leaders to reduce leaders’ perceived threat to hierarchy. On the other hand, subordinates can actively demonstrate their instrumental value and increase leader perceived power dependence on them. For example, employees can enhance their work skills or build personal bonds with leaders to facilitate Machiavellian leaders’ goal attainment.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the theoretical and practical implications of this study, several limitations should be noted. First, this study focuses on the moderating role of leader position power to explain when Machiavellian leaders may engage in abusive supervision. Leader position power primarily stems from one’s formal role within the organization. Future research may further consider the influence of other sources of power, such as leader personal power (Cheng et al., 2022). Leaders typically acquire personal power through their work experiences and knowledge (i.e., expert power), or through the support of their subordinates (i.e., referent power) (French & Raven, 1959). It would be interesting to explore whether different sources of leader power moderate Machiavellian leaders’ trait expressions in distinct ways.

Apart from individual power-related factors, future research can also examine how power-related context may influence Machiavellian leaders’ trait expressions. For example, in highly political environments, there is a lack of clear norms to guide individuals’ behavior, which provides opportunities for leaders to exercise their authority more freely (Cheng et al., 2022). Consequently, Machiavellian leaders may have a stronger motivation to defend their authority and be more likely to view subordinates as threats. Therefore, we encourage future research to examine how organizational politics would shape the effect of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision via leader perceived threat to hierarchy and leader perceived power dependence on subordinates respectively.

Second, this study examines the power-threatening and power-sustaining processes to capture the complexity of Machiavellian leaders. Although uncovering the opposite effect of these two processes on abusive supervision is insightful, it is also interesting to see whether these two processes can lead to different behavioral outcomes, especially the power-sustaining process. Considering that Machiavellian leaders are likely to perceive high dependence on subordinates, apart from reducing abusive supervision to maintain their power, Machiavellian leaders may engage in more active strategies such as seeking proximity to team members and knowledge sharing with team members to enhance their power in the team. Indeed, recent research found that highly dominance-oriented individuals (similar to Machiavellian individuals) tend to affiliate with their in-group competitors to maintain status and control threats (Mead & Maner, 2012). Therefore, considering that Machiavellian individuals are flexible in using various manipulation tactics, future research could further explore those different behavioral consequences.

Third, we dropped 13 groups with negative Rwg(j) values of abusive supervision when conducting data analysis. Negative Rwg values indicate significant discrepancies in the perceptions of abusive supervision among members within these groups. As team members can differ in their abilities and motivations (Doerr et al., 2004), it is plausible that leaders may also hold distinct perceptions or attitudes toward different members. Indeed, studies have suggested that leaders exhibit varied levels of mistreatment towards members of the same team (Ogunfowora, 2013). For example, leaders tend to be more abusive toward subordinates who are high on negative affectivity compared to those who are low on negative affectivity (Tepper et al., 2006). Consequently, members of the same team may experience different levels of abusive supervision. Given that we theorized abusive supervision as a group-level construct, we excluded 13 groups with negative Rwg(j) values of abusive supervision from the regression analysis, because these groups demonstrated a lack of agreement among employees on experienced abusive supervision. We encourage future research to explore factors that contribute to the discrepancies in perceptions of abusive supervision among employees within a team.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our research advances scholarly understanding of how and when leader Machiavellianism increases versus decreases abusive supervision. Although prior researchers suggest divergent relationships between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision, few studies unpack the underlying mechanisms of these relationships. Drawing from trait activation theory as the overarching theory, we investigate the power-threatening (i.e., leader perceived threat to hierarchy) and power-sustaining processes (i.e., leader perceived power dependence on subordinates) that respectively shape the positive and negative effects of leader Machiavellianism on abusive supervision, as well as the boundary role of leader position power in shaping these processes. Therefore, we examine the complex and multifaceted relationship between leader Machiavellianism and abusive supervision. We hope that our research can motivate more comprehensive inquiries into this paradoxical relationship, thereby advancing our theoretical understanding of Machiavellian personality.

Data availability

Data used in this study will be available from the authors upon request.

Notes

These detailed results are available from the authors upon request.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc.

Anderson, C., & Brion, S. (2014). Perspectives on power in organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 67–97. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091259.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (2005). Yes, personality matters: Moving on to more important matters. Human Performance, 18, 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1804_3.

Belschak, F. D., Hartog, D., D. N., & Kalshoven, K. (2013). Leading machiavellians: How to translate machiavellians’ selfishness into pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Management, 41(7), 1934–1956. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313484513.

Bereczkei, T. (2018). Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis revisited: What evolved cognitive and social skills may underlie human manipulation. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 12(1), 32–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000096.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner, & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research (pp. 137–164). Sage Publications, Inc.

Chan, D. (1998). Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.234

Chen, G., & Bliese, P. D. (2002). The role of different levels of leadership in predicting self- and collective efficacy: Evidence for discontinuity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.549.

Chen, G., Kirkman, B. L., Kanfer, R., Allen, D., & Rosen, B. (2007). A multilevel study of leadership, empowerment, and performance in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.331.

Cheng, Y. N., Hu, C., Wang, S., & Huang, J. C. (2022). Political context matters: A joint effect of coercive power and perceived organizational politics on abusive supervision and silence. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 41, 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-022-09840-x.

Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2023). Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09871-y.

Christie, R., & Geis, F. L. (1970). Studies in Machiavellianism. Elsevier.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,.

Colquitt, J. A., & Zapata-Phelan, C. P. (2007). Trends in theory building and theory testing: A five-decade study of the Academy of Management Journal. Academy of Management Journal, 50(6), 1281–1303. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2007.28165855.

Dahling, J. J., Whitaker, B. G., & Levy, P. E. (2008). The development and validation of a new Machiavellianism scale. Journal of Management, 35(2), 219–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308318618.

Davis, M. D., & Stephan, W. G. (2011). Electromyographic analyses of responses to intergroup threat. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(1), 196–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00709.x.

De Hoogh, A. H. B., Hartog, D., D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2021). Showing one’s true colors: Leader Machiavellianism, rules and instrumental climate, and abusive supervision. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(7), 851–866. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2536.

Deluga, R. J. (2001). American presidential machiavellianism: Implications for charismatic leadership and rated performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 12(3), 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(01)00082-0.

Doerr, K. H., Freed, T., Mitchell, T. R., Schriesheim, C. A., & Zhou, X. (2004). Workflow policy and within-worker and between-workers variability in performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(5), 911–921. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.911.

Drory, A., & Gluskinos, U. (1980). Machiavellianism and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65(3), 81–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.65.1.81.

Dust, S. B., Liu, H., Wang, S., & Reina, C. S. (2022). The effect of mindfulness and job demands on motivation and performance trajectories across the workweek: An entrainment theory perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(2), 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000887.

Farmer, S. M., & Aguinis, H. (2005). Accounting for subordinate perceptions of supervisor power: An identity-dependence model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1069–1083. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1069.

Fehr, B., Samsom, E., & Paulhus, D. L. (1992). The construct of Machiavellianism: Twenty years later. In C. D. Spielberger, & J. N. Butcher (Eds.), Advances in Personality Assessment (pp. 77–116). Erlbaum.

Feng, Z., Keng-Highberger, F., Yam, K. C., Chen, X. P., & Li, H. (2022). Wolves in sheep’s clothing: How and when machiavellian leaders demonstrate strategic abuse. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05132-y.

Ferris, G. R., Zinko, R., Brouer, R. L., Buckley, M. R., & Harvey, M. G. (2007). Strategic bullying as a supplementary, balanced perspective on destructive leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.004.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104.

French, J. R. P. Jr., & Raven, B. (1959). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright (Ed.), Studies in social power (pp. 150–167). Univer. Michigan.

Galie, P., & Bopst, C. (2006). Machiavelli & Modern Business: Realist thought in contemporary corporate leadership manuals. Journal of Business Ethics, 65(3), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-5352-1.

Galinsky, A. D., Magee, J. C., Gruenfeld, D. H., Whitson, J. A., & Liljenquist, K. A. (2008). Power reduces the press of the situation: Implications for creativity, conformity, and dissonance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1450–1466. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012633.

Gargiulo, M., & Ertug, G. (2014). The power of the weak. Contemporary perspectives on organizational social networks (Vol. 40, pp. 179–198). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Garson, G. D. (2008). Structural equation modeling. Retrieved April 7, 2008, from http://www2.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/pa765/structur.htm.

Geis, F. L., & Moon, T. H. (1981). Machiavellianism and deception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 766–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.41.4.766.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

Harvey, P., Harris, K. J., Gillis, W. E., & Martinko, M. J. (2014). Abusive supervision and the entitled employee. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(2), 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.08.001.

Heller, S., Ullrich, J., & Mast, M. S. (2023). Power at work: Linking objective power to psychological power. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 53(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12922.

Hirsh, J. B., Galinsky, A. D., & Zhong, C. B. (2011). Drunk, powerful, and in the dark: How general processes of disinhibition produce both prosocial and antisocial behavior. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(5), 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611416992.

James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1984). Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(1), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.1.85.

Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2009). Machiavellianism. In M. R. Leary, & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 93–108). The Guilford.

Keltner, D., van Kleef, G. A., Chen, S., & Kraus, M. (2008). A reciprocal influence model of social power: Emerging principles and lines of inquiry. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 151–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00003-2.

Kessler, S. R., Bandelli, A. C., Spector, P. E., Borman, W. C., Nelson, C. E., & Penney, L. M. (2010). Re-examining Machiavelli: A three-dimensional model of Machiavellianism in the workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(8), 1868–1896. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00643.x.

Khan, A. K., Moss, S., Quratulain, S., & Hameed, I. (2018). When and how subordinate performance leads to abusive supervision: A social dominance perspective. Journal of Management, 44(7), 2801–2826. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316653930.

Khan, A. K., Hameed, I., Quratulain, S., Arain, G. A., & Newman, A. (2023). How the supervisor’s machiavellianism results in abusive supervision: Understanding the role of the supervisor’s competitive worldviews and subordinate’s performance. Personnel Review, 52(4), 992–1009. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2021-0176.

Kiazad, K., Restubog, S. L. D., Zagenczyk, T. J., Kiewitz, C., & Tang, R. L. (2010). In pursuit of power: The role of authoritarian leadership in the relationship between supervisors’ machiavellianism and subordinates’ perceptions of abusive supervisory behavior. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(4), 512–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2010.06.004.

Klein, K. J., Conn, A. B., Smith, D. B., & Sorra, J. S. (2001). Is everyone in agreement? An exploration of within-group agreement in employee perceptions of the work environment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.3.

Kunce, J. T., Cook, D. W., & Miller, D. E. (1975). Random variables and correlational overkill. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 35(3), 529–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447503500301.

LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106296642.

Lee, F., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2001). 2. Is it lonely at the top? The independence and interdependence of power holders. Research in Organizational Behavior, 23, 43–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(01)23003-2.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1.

Liu, D., Liao, H., & Loi, R. (2012). The dark side of leadership: A three-level investigation of the cascading effect of abusive supervision on employee creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1187–1212. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0400.

Magee, J. C., & Smith, P. K. (2013). The social distance theory of power. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(2), 158–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868312472732.