Abstract

The increasing chronicity and multimorbidities associated with people living with HIV have posed important challenges to health systems across the world. In this context, payment models hold the potential to improve care across a spectrum of clinical conditions. This study aims to systematically review the evidence of HIV performance-based payments models. Literature searches were conducted in March 2020 using multiple databases and manual searches of relevant papers. Papers were limited to any study design that considers the real-world utilisation of performance-based payment models applied to the HIV domain. A total of 23 full-text papers were included. Due to the heterogeneity of study designs, the multiple types of interventions and its implementation across distinct areas of HIV care, direct comparisons between studies were deemed unsuitable. Most evidence focused on healthcare users (83%), seeking to directly affect patients' behaviour based on principles of behavioural economics. Despite the variability between interventions, the implementation of performance-based payment models led to either a neutral or positive impact throughout the HIV care continuum. Moreover, this improvement was likely to be cost-effective or, at least, did not compromise the healthcare system’s financial sustainability. However, more research is needed to assess the durability of incentives and its appropriate relative magnitude.

Resumen

La creciente cronicidad y multimorbilidades asociadas con las personas que viven con el VIH han planteado importantes desafíos para los sistemas de salud en todo el mundo. En este contexto, los modelos de pago tienen el potencial de mejorar la atención en un espectro de condiciones clínicas. Este estudio tiene como objetivo revisar sistemáticamente la evidencia de los modelos de pagos basados en el desempeño aplicados al dominio del VIH. Las búsquedas bibliográficas se realizaron en marzo de 2020 utilizando múltiples bases de datos y búsquedas manuales de artículos relevantes. Los artículos se limitaron a cualquier diseño de estudio que considere la utilización en el mundo real de modelos de pago basados en el desempeño aplicados al dominio del VIH. Se incluyeron un total de 23 artículos de texto completo. Debido a la heterogeneidad de los diseños de los estudios, los múltiples tipos de intervenciones y su implementación en distintas áreas de la atención del VIH, las comparaciones directas entre diferentes estudios se consideraron inadecuadas. La mayoría de la evidencia se centró en los usuarios de la salud (83%), buscando afectar directamente el comportamiento de los pacientes basándose en los principios de la economía del comportamiento. A pesar de la variabilidad entre las intervenciones, la implementación de modelos de pago basados en el desempeño generó un impacto neutral o positivo en todo el proceso de atención del VIH. Además, es probable que esta mejora sea costo-efectiva o, al menos, no comprometa la sostenibilidad financiera del sistema de salud. Sin embargo, se necesita más investigación para evaluar la durabilidad de los incentivos y su magnitud relativa apropiada.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The HIV / AIDS epidemiological evolution remains challenging across the world. Whilst low to intermediate-income countries have focused on tackling new infections and the spread of the disease, the epidemiological evolution in high-income countries has led to people with HIV living longer, and with multiple comorbidities [1]. This increase in chronicity and multimorbidities associated with people living with HIV is posing important challenges to health systems across the world [2]. In fact, given the increasing medical costs per person living with HIV infection [3] and the ever-growing budget constraints, transformational changes in both the HIV care delivery and payment models are required [4].

Multiple payment models have been tested in healthcare, typically characterised based on its: (i) recipients; and (ii) payment unit(s). First, concerning the model’s recipients, payment models are typically utilised to reimburse healthcare providers for their services. However, payment models are also used to cascade down institutional incentives to the individual level, either to incentivise healthcare professionals or the healthcare users themselves. Second, regarding the unit payment, historical unit payments centered on retrospective cost reimbursements have been progressively replaced with prospective unit payments, particularly based on activity (e.g. fee-for-service, bundled payments per episode or per diagnosis) or capita. More recently, payment models have moved from volume to value-based unit payments, with the implementation of performance-based payment models which aim to improve quality of care and decrease overall costs [5]. Different unit payments present diverse advantages and disadvantages, leading to the coexistence of multiple unit payments across different production lines (e.g. ambulatory care, admissions), care providers or even healthcare systems [2, 3]. As an example, if the model’s aim is to improve healthcare access, then volume-based unit payments may be appropriate, whilst if the aim is to enhance disease prevention, the capita unit payment system may be more appropriate. In essence, the payment model’s structure should be aligned with its overall aim.

Given the high mean healthcare cost per person living with HIV infection [3], payment models must balance: (i) the financial risk for all stakeholders; (ii) the promotion of quality of care and care integration [1, 2]; and (iii) multiple recipients, from healthcare providers, healthcare professionals or even the people living with HIV themselves [6]. For these reasons, novel HIV payment models tend to be performance-based as opposed to volume-based.

Over the past decade, multiple reviews evaluated the impact of performance-based HIV payment models [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], which can be grouped according to: the healthcare setting considered (low to intermediate-income countries vs high-income countries); and the area of HIV care considered (from HIV testing and HIV prevention to adherence to treatment). Notably, a systematic literature review published in 2017 assessed the implementation of performance-based payment models in low-income countries [13]. Only four studies were included in this review and the authors concluded there was little evidence regarding the real-world implementation of HIV payment models.

The present manuscript builds upon previous reviews but presents four innovative features. First, contrary to previous studies that only consider high or low-income countries, this review did not exclude evidence based on the study’s country of origin. Second, this review aimed to capture any performance-based payment model regardless of its recipient (healthcare providers, health professionals or healthcare users). Third, the entire HIV continuum of care was considered, from prevention to the treatment of people living with HIV. Previous evidence tended to focus on a specific area, either HIV prevention, adherence to treatment or the delivery of antiretroviral treatment (ART). Fourth, linked to the increasing chronicity of HIV in high-income countries, the review included search terms concerning the use of payment models in the context of multimorbidity.

As a corollary, this systematic literature review aims to summarise the real-world evidence around the implementation of HIV performance-based payment models and provide a solid foundation on which to base decisions from healthcare policy makers across multiple healthcare settings.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted to analyse any empirical evidence around the implementation of payment models in the field of HIV / AIDS. This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement using a pre-defined protocol (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO identification number CRD42020167941) [16].

Search Strategy and Databases

The search strategy was defined based on the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study design) framework, as summarised in Table 1. The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE (PubMed), SCOPUS, Emerald, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. The search strategy (Online Appendix 1) was consistently used in the databases searched, with only minor adjustments specific to the database searched. The use of truncation, wildcards, and Boolean logic aimed at maximising the number of relevant articles. In addition, references cited in the identified papers were also examined. In summary, the search strategy aimed to include studies of any design which evaluated the clinical and/or financial impact of implementing real-world payment models across the HIV continuum of care.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined as per the PICOS strategy (Table 1). As inclusion criteria we considered: (i) studies including adults living with HIV/AIDS aged 18 years or older (studies including children were included if the data had been disaggregated by age group for adults aged ≥ 18 years); (ii) studies, regardless of its design, in which clinical and/or economic outcomes related to the implementation of performance-based payment models were considered; (iii) studies published from 01/01/2008 onwards; and (iv) studies published in English. The age group was limited to adults as performance-based payment models are typically aimed at adults who live with the HIV infection or are at-risk of contracting the infection. With regards to the time frame, the utilisation of behavioural economics applied to the HIV domain has been quite recent, particularly after the introduction of HIV antiretroviral drugs. As an exclusion criterion, non-human studies were excluded.

Screening and Data Extraction

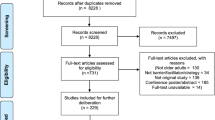

Figure 1 illustrates the process of study selection and data extraction. Abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers (TR, DB) and included or excluded as per the screening protocol. Full texts of selected articles were retrieved and independently assessed by two reviewers (TR, DB) for consistency in alignment with the review’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. Both investigators indicated the reason(s) to include or not include each study in the systematic review. Any disagreements in the screening of abstracts and data extraction from full text papers were reached through consensus and, if not possible, by a third reviewer (VN). The data extraction methodology considered the collation of the following data in an electronic form spreadsheet (using Microsoft Excel):

-

Study description: record number, authors, study title, year, journal, country, study period, source of funding (e.g. public, private, social sector), reference, study methods;

-

Study and participant details: study objectives, study design, study inclusion and exclusion criteria, recruitment procedures used, participants’ allocation methods, population description (e.g. age, sex, socio-economic status of participants, sample size, CD4 count, ART status);

-

Intervention and reported outcomes: intervention and comparator, primary and secondary outcomes measures, period of follow up, subgroup analysis, subgroup details (if applicable), sensitivity analysis;

-

Key findings, summary of study strengths and limitations.

All bibliographic references were managed (e.g. elimination of duplicates) using the bibliography management software Zotero.

Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (TR, DB) assessed the risk of bias of each included study using the ‘Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT)’ [17]. MMAT contains 19 core criteria in a quality scoring system which are grouped into five methodological categories, according to the study design: qualitative, quantitative with randomisation, quantitative without randomisation, quantitative descriptive studies and mixed methods.

Results

A total of 23 full text studies were included in the review (see Fig. 1). These presented different methodologies in terms of: study design; country of origin; recipient of the intervention; type of intervention; clinical evidence; and economic evidence. For these reasons it was not deemed appropriate to summarise the evidence using meta-analyses and instead a descriptive synthesis of evidence was undertaken. Table 2 summarises the key methodological information extracted from the 23 studies included. Table 3 illustrates the clinical and economic results from the 23 studies included in this systematic review (for detailed information please refer to Online Appendix II). The evidence in the appendices are listed in chronological order (newest to oldest) and grouped per study design.

Study Design

Of the 23 articles included, 15 (65%) articles reported randomised clinical trials [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33], 4 (17%) non-randomised empirical studies [34,35,36,37] and 4 (17%) quantitative descriptive studies with cost-effectiveness analyses [38,39,40,41].

Country of Origin

The studies included were classified according to their country of origin (see Table 2), given that interventions with payment models have the potential to be diversified according to the country in which the intervention is implemented. Thirteen out of 23 (57%) papers were derived from countries with high-income levels, specifically the USA (11 studies), the UK and Australia (1 study each). The remaining 10 (43%) articles were derived from several African countries with low to medium-income levels: Uganda (3 studies), Tanzania (2 studies) and Malawi, South Africa, Mozambique, Swaziland and Rwanda (1 study each).

Intervention’s Recipient

The payment model may also vary depending on its recipients: (i) health organisations; (ii) health professionals; and (iii) health care users themselves. A total of 19 of 23 articles (83%) focused on health users, followed by 7 of 23 (30%) articles with an emphasis on health organisations and no evidence on healthcare professionals. Three articles simultaneously incentivised health organisations and health care users.

Type of Intervention

Different studies have considered various interventions, particularly regarding the model’s unit payment. However, the evidence presented a common denominator as all interventions that aimed to change the behaviour of health users deployed positive financial incentives.

All seven papers that focused on health organisations considered the use of incentives based on pay-for-performance. However, the rationale inherent as to how incentives aimed to change organisational behaviours varied, as did the area of HIV on which the incentives were focused. At the health care users’ level, the empirical evidence (19 articles) concentrated mostly on the use of financial incentives to change behaviours across the various areas of HIV. These financial incentives were always positive incentives, with a view of promoting appropriate behaviour, and not negative incentives aimed at inhibiting incorrect behaviours. However, these incentives varied greatly in terms of structure, with financial incentives being attributed as: (i) a fixed component, where incentives were paid to all participants regardless of the results obtained; (ii) based on a lottery, where only one or more participants received incentives based on a random draw; and / or (iii) a conditional component, where there is only room for payment (partial or total) depending on the achievement of certain objectives, usually around clinical indicators associated with HIV management. It should be noted that most studies in low-income countries considered the use of fixed incentives whilst in high-income countries these tended to be conditional. Moreover, different incentive structures were not mutually exclusive, as some payment models were hybrid, with fixed incentives complemented by conditional ones. In addition, in countries with low to intermediate income levels, some models included the use of non-financial incentives, such as the allocation of food items or food vouchers.

Clinical Evidence

The clinical evidence presented in the systematic review was grouped along the continuum of HIV care according to five areas: (i) HIV prevention; (ii) HIV testing and screening; (iii) link to HIV care and initiation of antiretroviral therapy; (iv) retention in health care and adherence to treatment; and (v) viral suppression. Table 3 illustrates the empirical clinical evidence taken from the 23 studies, with the detailed view presented in Online Appendix II. Prospective studies, such as randomised clinical trials and observational studies, tended to be restricted to only one or two areas of HIV and not to the complete continuum of care. Irrespective of the study considered, the implementation of payment models led either to a neutral or positive impact across the five areas of HIV considered (Table 3). As an example, a recent randomised clinical trial by El-Sadr et al. (2019) [19] assessed the impact of individual financial incentives in two areas of HIV care: continuity of healthcare (proportion of patients with CD4 + count in 4 of the last 5 quarters); and viral suppression (proportion of patients with a viral load below 400 copies per ml among patients with at least 2 counts in the last 5 quarters). A higher proportion of participants in the intervention group showed greater continuity of health care compared to the control group (7.5%, p = 0.007, t-test) and exhibited a trend towards improved HIV viral suppression (2.7%, p = 0.076, t-test).

Economic Evidence

Regarding the magnitude of incentives, empirical evidence suggests that, regardless of the model’s recipient, the probability of influencing behaviours increases with the respective magnitude of the incentive (see Online Appendix II). In other words, the greater the incentive, the more likely to influence behaviours. Moreover, in the context of behavioural economics, more than the absolute value of the incentive, it is important to relate the magnitude of the incentive to the level of income of each participant (relative value of the incentive compared to the level of income of the participant). For example, studies carried out on the African continent presented lower incentives [between $ 1 and $ 40 when compared to high-income countries, such as the USA (average cost between $ 100 and $ 1173)], but their relative value compared to the respective average income per participant tends to be comparable or even higher.

Only one study analysed the durability of the results following the implementation of the payment model [19]. In this study, a randomised clinical trial [19], the findings from the payment model were sustained 9 months post its implementation.

Critical Appraisal

The risk of bias associated with each study was assessed using the MMAT. Fifty-two percent (12/23) of papers included presented ‘high quality’, 43% (10/23) ‘intermediate quality’ and 4.3% (1/23) ‘low quality’ (Table 2). Randomised controlled trials and modelling studies (cost-effectiveness studies) scored higher compared to non-randomised trials.

Discussion

Despite the design of the search terms, aimed at maximising the empirical evidence to include, the systematic literature review demonstrated the existence of limited empirical evidence around the implementation of payment models in the field of HIV and / or multimorbidities. The 23 articles included in the review showed important differences, concerning: (i) the country of origin; (ii) the type of study; (iii) recipient of the model; (iv) HIV care area considered; and (v) the type of intervention considered.

First, 57% (13/23) of the papers came from high-income countries, particularly the USA (11/13). The remaining 43% (10/23) studies come from seven countries on the African continent. The main difference between studies from low and high-income countries resided in the area of HIV care that the model seeks to impact, and not the type of study or the intervention’s recipient. Studies from low-income countries tended to focus on HIV prevention, HIV testing and screening, linkage to HIV care and initiation of antiretroviral therapy, whilst high-income countries tended to target subsequent dimensions of the continuum of care, in particular health care retention, adherence to treatment and viral suppression. This evidence seems to be consistent with the key issues that the interventions tried to address. The high incidence and vertical transmission of HIV in African countries is the key issues that health systems currently face, whereas in high-income countries, health systems have more difficulties around the integration of care, retaining people with HIV in antiretroviral therapy and ultimately suppress viral load.

Second, there were no differences concerning the impact of different payment models depending on the type of study, with all studies showing either a neutral or positive impact.

Third, the interventions centred on two distinct levels of recipients, health organisations and health care users themselves. No study aimed to incentivise health professionals. Most evidence focused on health care users (83%), followed by health organisations (30%). The fact that most interventions targeted health users themselves, i.e. people at higher risk of HIV infection and/or people living with HIV infection, is aligned with behavioural economics theories [41] and reflects the individual importance of the user in the context of the entire care continuum. The inherent rationale is that health systems should devote financial resources to change the way users behave, seeking to enhance the cost-effectiveness of the care provided. Although this approach is consistent and independent of the health system considered, there is an important difference depending on the income level of the country of origin. Low-income countries aimed to promote cost-effectiveness by focusing on reducing infection rates and the initiation of antiretroviral therapy whilst high-income countries focused on promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy and, ultimately, achieve viral suppression. The inherent rationale is to improve quality of life of people living with HIV, while avoiding costly episodes of hospitalisation in patients without viral suppression.

Fourth, five areas along the HIV care continuum were considered. As illustrated in Table 2, different papers focused on one or several areas, with 43% (10/23) of articles assessing the impact on viral suppression, followed by 30% (10/23) around HIV prevention and retention in healthcare and adherence to treatment and 22% (5/23) in the remaining areas (HIV testing and screening; link to HIV care and early antiretroviral therapy). It should be noted that the evidence surrounding viral suppression derived mainly from high-income countries.

Fifth, about the intervention, i.e. the payment model, this usually includes the use of financial incentives to encourage both health organisations and their users. These payments were mostly fixed, followed by conditional payments or based on lotteries. The use of conditional incentives is particularly relevant in: (i) care retention, where the user or organisation is only reimbursed according to consecutive indicators of access to care (e.g. consecutive CD4 counts); and (ii) viral suppression, where the user or organisation is only incentivised if viral suppression is achieved and/or sustained (e.g. CD4 counts below a given clinical objective). Contrary to some theory of behavioural economics, these incentives were always of a positive nature, that is, aimed at promoting behaviours, and not negative ones, which aim to inhibit behaviours (“carrot and not the stick”). A final point was the use of non-financial incentives (e.g. food items, smart phones) in studies developed in low-income countries.

Despite these methodological differences, the implementation of payment models presented a neutral or positive impact throughout the HIV care continuum. In fact, no study has shown a negative impact from applying the intervention with a payment model. This means that payment models improved the care provided under different dimensions of analysis, particularly in terms of access and quality of care. In particular, one high-quality randomised clinical trial conducted in the USA (HPTN 065 study) showed that the use of payment models led to a statistically significant improvement in the suppression of HIV viral loads [27]. These findings, consistent throughout the evidence analysed, seem to reflect the potential for pay-for-performance to improve HIV care. However, publication biases were not formally assessed.

Additionally, the financial impact of the intervention appears to be aligned with the financial sustainability of the health system itself. When considering the four studies that evaluated the cost-effectiveness of HIV payment models [38,39,40,41], these were found to have a high probability of being cost-effective taking into account the usual financial envelopes of the health systems (“willingness-to-pay thresholds”). This means that the interventions represent “value for money” and the increased costs associated with the payment model were more than offset by the avoided costs and / or by improving the quality of life of people living with HIV infection.

In terms of economic findings, the magnitude of the payment seems to be associated with the probability of success of the respective intervention. In the context of behavioural economics, more than the specific value of the incentive (absolute value), it is important to relate the magnitude of the incentive to the level of income of each participant (relative value of the incentive compared to the level of income of the participant). Finally, there was little evidence regarding the durability of the impact of the intervention. More research is needed to understand the long-term implications and sustainability of payment models in changing organisational and patients’ behaviours.

Lastly, payment models in the HIV domain are at an early stage of development. This situation is similar to the payment models used in the context of patients with multimorbidity [42]. However, due to the increasing chronicity associated with HIV, novel payment models should consider HIV in the context of other clinical conditions (e.g. diabetes, mental health). Also, general payment models hold the potential to indirectly affect HIV care. For instance, a payment model that incentivises healthy habits or diabetes care holds the potential to impact patients who also live with an HIV infection. For these reasons, further research on the real-world implementation and cost-effectiveness of new or novel payment models is strongly recommended.

Review Limitations

The present review covers a period of 12 years (since 2008). The authors believe the exclusion of studies prior to 2008 constitutes a minor limitation as most relevant performance-based payment models, particularly in high-income countries, were constituted following the introduction of HIV antiretroviral drugs. The review includes only HIV specific performance-based payment models. Therefore, the potential impact of generic payment models across HIV patients is not included, which constitutes a review limitation. Given its broad inclusion criteria, all range and heterogeneity of studies conducted in different health care settings were included in the review. Despite this, a small number of studies (23) were included. The quality of these studies was assessed using the MMAT methodology, but no individual assessment of publication biases was conducted. Although a limitation, the authors believe that the review’s findings are likely to reflect the real-world implementation of HIV-based performance payment models. Lastly, given the non-comparability of the studies retrieved, we conducted a narrative review and not a meta-analysis.

Conclusion

This review summarised the evidence around the use of performance-based payment models in the context of HIV and multimorbidity. Despite the very limited amount of evidence and its heterogeneity, the utilisation of payment models seemed to be associated with neutral or positive impact across different dimensions of HIV care and was likely to be cost-effective. However, the optimal magnitude of the incentives, as well as its long-term durability, remains unclear and therefore further research is recommended.

Availability of Data and Material

Data available upon request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral treatment

- MMAT:

-

Mixed Method Appraisal Tool

- USA:

-

United States of America

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

Oliva-Moreno J, Trapero-Bertran M. Economic Impact of HIV in the Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Era - Reflections Looking Forward. AIDS Rev. 2018;20(4):226–35. https://doi.org/10.24875/AIDSRev.M17000011.

Struckmann V, Quentin W, Busse R, van Ginneken E. How to strengthen financing mechanisms to promote care for people with multimorbidity in Europe? Copenhagen (Denmark): European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2017.

Johnson C et al., Systematic review of HIV testing costs in high and low income settings. World Health Organization, 2015. Accessed: Sep. 07, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK316032/.

Srivastava S, Singh PK, Vatsalya V, Karch RC. Developments in the diagnostic techniques of infectious diseases: rural and urban prospective. Adv Infect Dis. 2018. https://doi.org/10.4236/aid.2018.83012.

Costa C, Santana R, Boto P. “Financiamento por capitação ajustada pelo risco : conceptualização e aplicação,” Rev. Port. Saúde Pública, Temático 7, 67–102, 2008.

Galarraga O, Sosa-Rubi SG. Conditional economic incentives to improve HIV prevention and treatment in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Hiv. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30233-4.

Touré H, Audibert M, Dabis F. To what extent could performance-based schemes help increase the effectiveness of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) programs in resource-limited settings? A summary of the published evidence. BMC Public Health. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-702.

Operario D, Kuo C, Sosa-Rubi SG, Galarraga O. Conditional economic incentives for reducing HIV risk behaviors: integration of psychology and behavioral economics. Health Psychol. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032760.

Galárraga O, Genberg BL, Martin RA, Barton Laws M, Wilson IB. Conditional economic incentives to improve HIV treatment adherence Literature review and theoretical considerations. AIDS Behav. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0415-2.

Lee R, Cui RR, Muessig KE, Thirumurthy H, Tucker JD. Incentivizing HIV/STI testing: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):905–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0588-8.

Bassett IV, Wilson D, Taaffe J, Freedberg KA. Financial incentives to improve progression through the HIV treatment cascade. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1097/COH.0000000000000196.

Taaffe J, Cheikh N, Wilson D. The use of cash transfers for HIV prevention–are we there yet? Afr J AIDS Res AJAR. 2016. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2015.1135296.

Suthar AB, Nagata JM, Nsanzimana S, Barnighausen T, Negussie EK, Doherty MC. Performance-based financing for improving HIV/AIDS service delivery: a systematic review. Bmc Health Serv Res. 2017;17:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1962-9.

Choko AT, Candfield S, Maheswaran H, Lepine A, Corbett EL, Fielding K. The effect of demand-side financial incentives for increasing linkage into HIV treatment and voluntary medical male circumcision: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207263.

Galárraga O, Sosa-Rubí SG. Conditional economic incentives to improve HIV prevention and treatment in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(10):e705–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30233-4.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Hong QN, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221.

Choko AT, et al. HIV self-testing alone or with additional interventions, including financial incentives, and linkage to care or prevention among male partners of antenatal care clinic attendees in Malawi: an adaptive multi-arm, multi-stage cluster randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002719.

El-Sadr WM, et al. Brief report: Durability of the effect of financial incentives on HIV viral load suppression and continuity in care: HPTN 065 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001927.

Thirumurthy H, et al. Financial incentives for achieving and maintaining viral suppression among HIV-positive adults in Uganda: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30330-8.

Kadota JL, et al. The heterogeneous effect of short-term transfers for improving ART adherence among HIV-infected Tanzanian adults. AIDS Care. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1476666.

Maughan-Brown B, et al. A conditional economic incentive fails to improve linkage to care and antiretroviral therapy initiation among HIV-positive adults in cape town, South Africa. AIDS Patient Care Stds. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2017.0238.

Mills EJ, et al. Unconditional cash transfers for clinical and economic outcomes among HIV-affected Ugandan households. AIDS Lond Engl. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001899.

Montoy JCC, Dow WH, Kaplan BC. Cash incentives versus defaults for HIV testing: a randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199833.

Chamie G, et al. Comparative effectiveness of novel nonmonetary incentives to promote HIV testing. AIDS Lond Engl. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001833.

Alsan M, et al. A commitment contract to achieve virologic suppression in poorly adherent patients with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Lond Engl. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001543.

El-Sadr W, et al. Financial incentives for linkage to care and viral suppression among HIV-positive patients: A randomized clinical trial (HPTN 065). JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1083–92. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2158.

Stitzer M, et al. Enhancing patient navigation to improve intervention session attendance and viral load suppression of persons with HIV and substance use: a secondary post hoc analysis of the Project HOPE study. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-017-0081-1.

Metsch LR, et al. Effect of patient navigation with or without financial incentives on viral suppression among hospitalized patients with hiv infection and substance use: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8914.

de Walque D, et al. Using provider performance incentives to increase HIV testing and counseling services in Rwanda. J Health Econ. 2015;40:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.12.001.

De Walque D, et al. Incentivising safe sex: a randomised trial of conditional cash transfers for HIV and sexually transmitted infection prevention in rural Tanzania. BMJ Open. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000747.

Barnett PG, Sorensen JL, Wong W, Haug NA, Hall SM. Effect of incentives for medication adherence on health care use and costs in methadone patients with HIV. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.017.

Belenky N, et al. Associations between Medicare part D and out-of-pocket spending, HIV viral load, adherence, and ADAP use in dual eligibles with HIV. Med Care. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000843.

Brantley AD, Burgess S, Bickham J, Wendell D, Gruber D. Using financial incentives to improve rates of viral suppression and engagement in care of patients receiving HIV care at 3 health clinics in Louisiana: The health models program, 2013–2016. Public Health Rep Wash DC 1974. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354918793096.

Rajkotia Y, et al. The effect of a performance-based financing program on HIV and maternal/child health services in Mozambique-an impact evaluation. Health Policy Plan. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx106.

Foster C, McDonald S, Frize G, Ayers S, Fidler S. ‘Payment by results’ - Financial incentives and motivational interviewing, adherence interventions in young adults with perinatally acquired HIV-1 infection: A pilot program. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2013.0262.

Wagner Z, Montoy JCC, Drabo EF, Dow WH. Incentives versus defaults: cost-effectiveness of behavioral approaches for HIV screening. AIDS Behav. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02425-8.

B. Adamson et al., “The Cost-Effectiveness of Financial Incentives for Viral Suppression: HPTN 065 Study.,” Value Health J. Int. Soc. Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res., 22: 194–202, 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.09.001.

Stevens ER, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a combination strategy to enhance the HIV care continuum in Swaziland: Link4Health. PLoS ONE. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204245.

Heymer K-J, Wentzlaff-Eggebert M, Mortimer E, Wilson DP. An economic case for providing free access to antiretroviral therapy for. Sex Health. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH10148.

Chang LL, DeVore AD, Granger BB, Eapen ZJ, Ariely D, Hernandez AF. Leveraging behavioral economics to improve heart failure care and outcomes. Circulation. 2017;136(8):765–72. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028380.

Stokes J, et al. Towards incentivising integration: A typology of payments for integrated care. Health Policy. 2018;122(9):963–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.07.003.

Funding

The systematic review was conducted as part of the project “Financiamento do VIH no continuum do percurso da pessoa com doença” [HIV financing in the continuum of the care path of the person with disease”] funded by the Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TR, DB, VN and AE conceptualised the study and developed the research protocol. TR and DB identified articles for full-text review. TR and DB extracted data from studies that met inclusion criteria. TR wrote the paper and all authors contributed comments for finalise the manuscript. All authors approved the final submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript. Furthermore, this research will not lead to the development of products.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rua, T., Brandão, D., Nicolau, V. et al. The Utilisation of Payment Models Across the HIV Continuum of Care: Systematic Review of Evidence. AIDS Behav 25, 4193–4208 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03329-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03329-2

Keywords

- Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- HIV infections

- Multimorbidity

- Healthcare Financing

- Payment Models

- Economic