Abstract

Food security and nutrition play an important role in HIV and TB care and treatment, including for improving treatment outcomes, adherence and uptake of HIV and TB care. This AIDS and behaviour supplement on “Adherence to HIV and TB care and treatment, the role of food security and nutrition” provides an overview of the current evidence and knowledge about the barriers to uptake and retention in HIV and TB treatment and care and on whether and how food and nutrition assistance can help overcome these barriers. It contains nine papers on three topic areas discussing: (a) adherence and food and nutrition security in context of HIV and TB, their definitions, measurement tools and the current situation; (b) food and nutrition insecurity as barriers to uptake and retention; and (c) food and nutrition assistance to increase uptake and retention in care and treatment. Future interventions in the areas of food security, nutrition and social protection for increasing access and adherence should be from an HIV sensitive lens, linking the continuum of care with health systems, food systems and the community, complementing existing platforms through partnerships and integrated services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Food security and nutrition play an important role in HIV and TB care and treatment, including for improving treatment outcomes, adherence and uptake of HIV and TB care. This AIDS and Behaviour supplement on “Adherence to HIV and TB care and treatment, the role of food security and nutrition” provides an overview of the current evidence and knowledge about the barriers to uptake and retention in HIV and TB treatment and care and on whether and how food and nutrition assistance can help overcome these barriers. This supplement is the result of a joint effort coordinated by WFP that started in the context of International AIDS Society conferences in Addis Ababa in 2011 and in Washington DC in 2012. While tremendous progress has been made in scaling up access to treatment, with covering up to 61 % of those eligible for treatment in 2012 [1], it is estimated that only 65 % of people living with HIV (PLHIV) in sub-Saharan Africa who initiate treatment remain on it after 3 years [2, 3]. Globally, HIV prevalence is increasing as AIDS-related deaths decrease because those receiving treatment are living longer healthier lives [4]. This means that long-term adherence and retention in care and treatment will be a challenge because if all the new WHO guideline recommendations were implemented globally, the number of people eligible for antiretroviral therapy will increase from 16.7 to 28.6 million in 2013 representing 86 % of all PLHIV in low- and middle-income countries [4, 5]. With this projected increase, adherence and retention, as well as the management and prevention of non-communicable diseases become more important [5, 6].

The Steadily Changing World of HIV and TB

The global response to HIV and TB has been shaped by many players, mainly through guidance from UNAIDS and WHO as well as resources channelled through the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), national development agencies and donors. The role of HIV and TB, which was very prominent in the Millenium Development Goals that guided priorities and action until 2015, is less clear in the post-2015 development agenda. This change has presented UNAIDS with a strategic opportunity for advocacy to ensure HIV is “prominently positioned in the post-2015 agenda, including ambitious, measurable targets towards the end of AIDS under an overarching health goal” [7]. This means that applying an HIV lens to other areas with higher prominence in the post-2015 development agenda such as food and nutrition security [8] becomes more important.

Since 2010, the global AIDS response adopted an evidence based strategic investment approach for maximum returns [9] and UNAIDS’ “Getting to Zero Strategy” of zero new infections, discrimination and AIDS-related deaths [10]. The UNAIDS’ investment framework [11, 12] takes on this new investment strategy [9] including its critical enablers and development synergies [13]. Social and programme enablers are part of the critical enablers and contribute to UNAIDS goals by creating demand for and helping improve existing interventions—including nutrition and social protection [9]. In the UNAIDS Division of Labour (DoL), WFP is the sole convener for the integration of food and nutrition in the HIV response [14, 15]. As one of the few UN agencies working on generating demand for HIV and TB services, WFP is complementing existing platforms through partnerships and contributing to UNAIDS “Getting to Zero strategy” by facilitating direct and or indirect access to food and adequate nutrition for those affected by HIV and TB –including vulnerable populations, women and girls and during the first 1,000 days of life, i.e. from conception to 24 months of age.

The HIV/AIDS and TB response has changed as countries are starting to align their national strategy plans and responses to WHO’s “Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection” released in 2013 [16] and its update from March 2014 [17]. To maximize the linkages and synergies with other key public health areas, WHO has developed a Global Health Sector Strategy on HIV/AIDS 2011–2015 [5] and a new Global Strategy for TB after 2015 [18], both approved at the 67th World Health Assembly in May 2014. Additionally, the Global Fund and its Strategy 2012–2016: “Investing for Impact” and its New Funding Model, require countries to use an investment approach and a prioritised and sustainable National Strategy Plan when applying for funds [19]. PEPFAR’s “Blue Print” strategy of creating an AIDS-free generation –focusing on partnerships, women and girls, monitoring and evaluation and ending stigma and discrimination to improve access and uptake of HIV services—lays a roadmap for USAID-funded activities globally [20]. Today’s approaches are based on National Strategy Plans that are context specific, that are led and developed in-country using an integrative and client-centred investment approach. While UNAIDS, WHO, PEPFAR and the Global Fund and others have integrated food and nutrition in their strategies, the generation of demand for access, uptake and retention in HIV and TB care remains a challenge which can also be better linked with food and nutrition strategies.

Adherence to HIV and TB Care and Treatment, the Role of Food Security and Nutrition

This supplement summarizes available evidence on the role of food security and nutrition in uptake and retention in care for HIV and TB and of ways to address issues related to food security and nutrition and their impact on uptake and adherence to care and treatment. The supplement’s nine papers are grouped into three main topic areas.

Adherence, Food Security and Nutrition

This section of the supplement includes papers discussing adherence, food security and nutrition in relation to HIV, including definitions, measurement tools and a description of the current situation. Stricker et al. [21] review critical elements of HIV care and ART adherence interventions as well as measurement methods and patient-related factors impacting on adherence and retention in care. Anema et al. [22] discuss definitions and indicators of food security in the context of HIV, highlighting opportunities for harmonization. Findings from this paper were presented at the Food and Nutrition Inter-Agency Task Team (IATT) face-to-face meeting in Cape Town, South Africa on December 12–13, 2013. Fielden et al. [23] analyse commonly used tools for measuring food and nutrition security, describing their use in the context of HIV.

Key messages on adherence to HIV care and treatment, food security and nutrition

-

Retention (in care) is the continued engagement in health services including the entire continuum of HIV care [21]

-

Adherence (to treatment) is the extent a client follows a prescribed medication or treatment regimen [21]

-

Inadequate retention and adherence lead to poor health outcomes (morbidity, mortality, drug resistances, risk of transmission) and reduced cost effectiveness (increased costs and lower productivity). The greatest loss to follow-up for HIV care occurs before starting treatment [21]

-

Lack of adherence to ART causes suboptimal viral suppression that may result in higher risk of developing drug resistance, transmission of such drug resistance and increasing treatment costs [21]

-

Adherence can be measured directly and indirectly; a good strategy is to use a combination of both [21]

-

The three components of food security (food sufficiency, dietary quality, and food safety) are useful for understanding and measuring food security needs of HIV-affected and other vulnerable groups [22]

-

Many of the existing tools measuring food and nutrition security have been adapted for the context of HIV. Considerations in selecting appropriate tools include subtypes (food sufficiency, dietary diversity and food safety); scope or level of application; and available resources [23]

-

Generalized food sufficiency and dietary diversity tools are useful to adequately measure food and nutrition security in HIV programming. Food consumption measurement tools provide further data for clinical research [23]

-

Food safety measurement is an important, but underdeveloped area in the context of HIV [23]

Food and Nutrition Insecurity as Barriers to Uptake and Retention

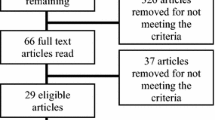

In this section Young et al. [24] review the role of food insecurity in adherence to care and treatment among adult and paediatric populations living with HIV. O’ HIarlaithe et al. [25] review and propose a classification of the barriers preventing women from accessing maternal and newborn child health (MNCH) and prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services (Table 1).

The findings and conclusions from O’ HIarlaithe et al. are in line to those of a recently published review by Phelps et al. on the linkages, initiation and retention of children in the HIV continuum of care (including individual, institutional, and systems barriers to diagnosing children with HIV, linkages to care and treatment, and reducing loss to follow-up). The review found that the provision of food has a role in improving retention and act as a barrier to accessing paediatric HIV care [26].

Key messages on food and nutrition insecurity as barriers to uptake and retention

-

Food insecurity has been found to be a critical barrier to adherence to ART and care among HIV- infected adults, HIV-infected pregnant women and their HIV-exposed infants, and child and adolescent PLHIV in both qualitative and quantitative studies [24]

-

Mechanisms to explain the linkages between food insecurity and ART non-adherence include: the exacerbation of hunger, ART side effects in the absence of adequate food and competing resource demands [24]

-

Interventions that address food insecurity may improve adherence to care and treatment for PLHIV [24]

-

Increased coverage or uptake of PMTCT services can be achieved if policy makers and programme managers understand access barriers [25]

-

Barriers to accessing PMTCT (Table 1) include social norms and knowledge, socioeconomic status, physiological status and psychological conditions. Economic and social factors are some of the most common demand side barriers. Transportation is the most frequently mentioned socioeconomic barrier. Non-disclosure, stigma and partner relations are the most commonly cited social barriers [25]

Food and Nutrition Assistance to Increase Uptake and Retention in Care and Treatment

This section of the supplement examines food and nutrition interventions as instruments to increase uptake and retention in HIV and TB care and treatment. Here, De Pee et al. [27] review studies where food assistance was used as an enabler to promote adherence to HIV and TB treatment. Grede et al. [28] focus on social and economic costs of TB by analysing the role of food assistance in mitigating the social and financial consequences of TB at individual and household levels. Aberman et al. [29] assess the global action in response to the AIDS epidemic in the context of food and nutrition security interventions as well as the evolution of policy supporting their integration into HIV programming. Martinez et al. conclude with a study from Honduras where the provision of household assistance in the form of a food basket and nutrition education improved adherence to HIV treatment by 20 % (p = 0.01) within 6 months among 400 clients with previous sub-optimal adherence [30].

Key messages on food and nutrition assistance to increase uptake and retention in care and treatment

-

The provision of food improved adherence and/or treatment completion for HIV care and treatment, ART or TB-DOTS in eight out of ten studies [27]

-

As a social protection measure, food assistance ensures food security and offsets some of the catastrophic costs of disease and their effect on the household [27]

-

Integrating food and nutrition support in HIV and TB care and support programmes and services is a good strategy to improve adherence to ART, retention in care and to rebuild livelihoods [27]

-

Creating enabling environments for this integration include: linking health systems (e.g. eligibility for therapeutic or supplementary food, integration of nutrition assessment counseling and support, linkages to HIV sensitive and HIV specific safety nets, referral systems to PMTCT and reproductive health, social protection, etc.) and communities (behavioral interventions at community level using task shifting and health care workers to track malnourished clients, creating nutrition support centers and referral systems) [27]

-

Socio-economic consequences of TB include stigma, social isolation, increased out-of-pocket expenditures for medical and non-medical costs and reduced income [28]

-

Social transfers in the form of food, cash or vouchers can mitigate the negative effects of TB by enabling diagnosis seeking behaviours, protecting minimum food expenditures, reducing the need to accumulate debt and reduce productive assets [28]

-

Social transfers also reduce the negative impacts on other household members, particularly young children and school-age children [28]

-

A current practice is the integration of nutrition assessment, counseling, and support (NACS) in the HIV response by strengthening links between nutrition and specific services by the health, agriculture, food security, social protection, education, and rural development sectors for more comprehensive care [29]

-

Nutrition supplementation and safety nets in the form of food assistance and livelihood interventions have potential in certain contexts to improve food security and nutrition outcomes in an HIV/AIDS context [29]

-

Providing household assistance in the form of a food basket along with nutrition education improved adherence to HIV treatment by 20 % (p = 0.01) among a group of non-adherent patients [30]

-

The impact of providing food and nutrition education can be measured with simple adherence indicators that include: missed clinic appointments, delayed prescription refills, and self-reported missed doses of ART [30]

Conclusion and Way Forward

This supplement provides an extensive review of evidence on the role of food security and nutrition in increasing seeking care, adherence to HIV and TB treatment and retention in care. It analyses barriers to uptake and retention in care and on whether and how food and nutrition assistance activities can help overcome some of these barriers. While interventions for initial access to treatment are important and life saving, there is an urgent need to develop a better understanding of retention in care and adherence across the entire continuum of care from HIV infection, to HIV testing, to pre-ART care and finally continuous lifelong ART. For maximum effectiveness, responses should address supply and demand of services for HIV and TB in a balanced manner. While global actions for increasing access to treatment have been successful, with 12.9 million people in low—and middle-income countries being on treatment at the end of 2013 [31], these have focused mainly on the supply side of healthcare services for HIV and TB. As treatment scale up strategies continue, attention to the demand-side, emphasizing access, uptake and adherence to care and treatment are essential. This supplement shows the importance of food security and nutrition support to strengthen the demand side of HIV and TB care and through that the uptake and outcome of treatment.

Strategies in the area of food security and social protection should include an HIV sensitive lens to increase access and adherence to HIV and TB care, and complement and link existing platforms through partnerships and integration of services. These interventions should: (a) be carefully planned to contribute to UNAIDS “Getting to Zero strategy” and “the end of AIDS” post 2015; (b) be context sensitive and aligned to sustainable country strategies and National Strategy Plans; (c) enable and improve uptake, adherence and retention in care by facilitating direct and or indirect access to food and adequate nutrition for those affected by HIV and TB and their households—including vulnerable populations, women and girls and during the first 1,000 days of life; (d) identify linkages and synergies with health systems and community members to generate demand for services [27, 32].

References

UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. [Internet]. UNAIDS. 2013 Nov 5; [cited 2014 Jun 25] pp. 1–198. [cited 2014 July 2]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf.

Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to 3 years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;29(15):1–15.

Kranzer K, Govindasamy D, Ford N, Johnston V, Lawn SD. Quantifying and addressing losses along the continuum of care for people living with HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. JIAS. 2012 Nov 19;15(2).

Maartens G, Celum C, Lewin SR. HIV infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. The Lancet. Elsevier Ltd; 2014 Jun 13;1–14.

WHO. The global health sector strategy on HIV/AIDS 2011–2015: an interim review of progress: abridged report, May 2014. WHO. Geneva; 2014 May 15;1–52.

Haregu TN, Oldenburg B, Setswe G, Elliott J, Nanayakkara V. Epidemiology of comorbidity of HIV/AIDS and non-communicable diseases in developing countries: a systematic review. J Glob Health Care Syst. 2012;2(1):1–12.

UNAIDS. Agenda item 3 - AIDS response in the Post-2015 Development Agenda. UNAIDS. 2013 May 28;(May 28 2013):1–23.

Kharas H. A new global partnership: eradicate poverty and transform economies through sustainable development. Coplan JH, editor. United Nations. New York; 2013 Jul 3;1–81.

Schwartlander B, Stover J, Hallett T, Atun R, Avila C, Gouws E, et al. Health policy towards an improved investment approach for an effective response to HIV/AIDS. The Lancet. Elsevier Ltd; 2011 Jun 11;377(9782):2031–41.

UNAIDS. Getting to Zero [Internet]. About UNAIDS. Geneva; 2010 [cited 2014 Jul 3]. pp. 1–64. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2010/jc2034_unaids_strategy_en.pdf.

A New Investment Framework for the Global HIV Response. UNAIDS [Internet]. 2011. Available from: http://icssupport.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/3-Investment-Framework-Summary-UNAIDS-Issues-Brief.pdf.

UNAIDS. Investing for results. Results for people. [Internet]. UNAIDS. Geneva; 2012 Jul 20;JC2359E:1–28. [cited 2014 Jun 30]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2012/JC2359_investing-for-results_en.pdf.

UNDP. Understanding and acting on critical enablers and development synergies for strategic investments. UNDP [Internet]. 2012 Dec 3;1–24. Available from: http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/hivaids/English/UNAIDS_UNDP_Enablers_and_Synergies_ENG.pdf.

UNAIDS. Consolidated guidance note: UNAIDS Division of Labour 2010. UNAIDS [Internet]. Geneva; 2011 Jan;1–60. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/JC2063_DivisionOfLabour_en.pdf.

Unaids WFP. UNAIDS cosponsor 2014 world food programme. UNAIDS. 2014;6:1–4.

WHO. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. WHO. 2013;1–272.

WHO. March 2014 supplement to the 2013 consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection recommendations for a public health approach [Internet]. WHO. Geneva; 2014 [cited 2014 Apr 23]. pp. 1–128. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/104264/1/9789241506830_eng.pdf?ua=1.

WHO. Draft global strategy and targets for TB prevention, care and control after 2015. WHO [Internet]. Geneva; 2014 Mar 12;1–24. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB134/B134_12-en.pdf.

GFATM. The global fund strategy 2012–2016: investing for impact [Internet]. Geneva: Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; 2011 [cited 2014 Jun 25]. pp. 1–22. Available from: http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/about/strategy/.

OGAC. PEPFAR Blueprint [Internet]. OGAC. Washington DC: The office of the global AIDS coordinator; 2012 [cited 2014 Jun 25]. Available from: http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/201386.pdf.

Stricker SM, Fox KA, Baggaley R, Negussie E, de Pee S, Grede N, Bloem M. Retention in care and adherence to ART are critical elements of HIV care interventions. AIDS Behav. 2013. doi:10.1007/s10461-013-0598-6.

Anema A, Fielden SJ, Castleman T, Grede N, Heap A, Bloem M. Food security in the context of HIV: towards harmonized definitions and indicators. AIDS Behav. 2013. doi:10.1007/s10461-013-0659-x.

Fielden SJ, Anema A, Fergusson P, Muldoon K, Grede N, de Pee S. Measuring food and nutrition security: tools and considerations for use among people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013. doi:10.1007/s10461-013-0669-8.

Young S, Wheeler AC, McCoy SI, Weiser SD. A review of the role of food insecurity in adherence to care and treatment among adult and pediatric populations living with HIV and AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2013. doi:10.1007/s10461-013-0547-4.

Hiarlaithe MO, Grede N, de Pee S, Bloem M. Economic and social factors are some of the most common barriers preventing women from accessing maternal and newborn child health (MNCH) and prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2014. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0756-5.

Phelps BR, Ahmed S, Amzel A, Diallo MO, Jacobs T, Kellerman SE, et al. Linkage, initiation and retention of children in the antiretroviral therapy cascade. AIDS. 2013;27:S207–13.

de Pee S, Grede N, Mehra D, Bloem MW. The enabling effect of food assistance in improving adherence and/or treatment completion for antiretroviral therapy and tuberculosis treatment: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2014. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0730-2.

Grede N, Claros JM, de Pee S, Bloem M. Is there a need to mitigate the social and financial consequences of tuberculosis at the individual and household level? AIDS Behav. 2014. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0732-0.

Aberman N-L, Rawat R, Drimie S, Claros JM, Kadiyala S. Food security and nutrition interventions in response to the aids epidemic: assessing global action and evidence. AIDS Behav. 2014. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0822-z.

Martinez H, Palar K, Linnemayr S, Smith A, Derose KP, Ramírez B, Farías H, et al. Tailored nutrition education and food assistance improve adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: evidence from Honduras. AIDS Behav. 2014. doi:10.1007/s10461-014-0786-z.

UNAIDS. The Gap Report [Internet]. UNAIDS. Geneva 2014 July 16; p. 12. [cited 2014 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf.

Mehra D, de Pee S, Bloem MW. Nutrition, food security, social protection and health systems strengthening for HIV programming, Chap. 4. In: Ivers L, editor. Food insecurity and public health. Boca Raton: CRC Press (in press).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Claros, J.M., de Pee, S. & Bloem, M.W. Adherence to HIV and TB Care and Treatment, the Role of Food Security and Nutrition. AIDS Behav 18 (Suppl 5), 459–464 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0870-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0870-4