Abstract

The sustainable development of rural areas involves guaranteeing the quality of life and well-being of people who live in those areas. Existing studies on farmer health and well-being have revealed high levels of stress and low well-being, with government regulations emerging as a key stressor. This ethnographic study takes smallholder farmers in two rural mountain areas of Italy, one in the central Alps and one in the northwest Apennines, as its focus. It asks how and why the current policy and regulatory context of agriculture affects farmer well-being. Interviews and participant observation were conducted with 104 farmers. Three common scenarios emerged that negatively affect farmer well-being. First, policies and regulations designed for lowland areas do not always make sense when applied in the mountains. Second, when subsidies are put into effect at the local level, the reality of their implementation can veer away from the original goals of the funding program and have unintended effects on farmer well-being, agricultural practices, and the environment. Finally, when regulations are implemented on farms in rural mountain areas, the primacy of a techno-scientific knowledge system over other, local and place-based knowledge systems is exposed. These three scenarios affect well-being by eliciting feelings of stress, frustration, and disillusionment; by reducing farmer control over their work; and by fostering the perception that farming is not valued by society. They also create conditions of inequality and insecurity. The ways in which government policies and regulations play out on mountain farms can erode trust in government institutions, lead to an us versus them mentality, and contribute to the further abandonment of agriculture and rural areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ludovico is a livestock farmer in his early 40s who works in the Alps of north-central Italy. Standing on the edge of his fields, he looked down on the valley a couple hundred meters below and to the Alps towering thousands of meters above. He spoke of his experiences applying for government grants and subsidies to support his small-scale farm holding. Like every other small-scale mountain farmer and beekeeper interviewed for this study, Ludovico talked about the complex regulations, policies, and programs that govern farming in the mountains in Italy. He spoke, unsolicited, of endless paperwork, regulations that seem disconnected from the realities of mountain farming, and complicated proposals for subsidies and grants: “It’s been ten years since I last applied for a grant because the thought of applying makes me vomit.” Other farmers expressed similar frustration and disillusionment, even downright revulsion, at the European Union (EU) and Italian regulations, policies, and programs governing their farming activities. It became clear that their sense of well-being has been affected by the multinational, national, provincial, and local regulatory context in which they have to operate.

These mountain farmers and beekeepers are not alone. Farmers across a range of developed countries experience high rates of stress, depression, and anxiety (Daghagh Yazd et al. 2019; Lundqvist et al. 2023; Younker & Radunovich 2021). Government regulations and policies have emerged as key stressors affecting farmer well-being in other countries as well (Kallioniemi et al. 2011, 2016; Logstein 2016; Scheurich et al. 2021; Simkin et al. 1998). What remains to be understood is how and why this is the case. The current study takes smallholder farmers and beekeepers in two rural mountain areas of Italy, one in the central Alps and one in the northwest Apennines, as its focus and asks how and why the current policy and regulatory context of agriculture affects farmer well-being. It identifies the pathways through which government policies, programs, and regulations act on the subjective well-being of smallholder farmers. The article concludes by assessing how this regulatory and policy context might be modified to promote farmer well-being.

Since the end of World War II, many residents of the Italian Alps and Apennines have left the mountains for economic opportunities in the lowlands and its major cities. The result has been the widespread abandonment of agriculture, rural depopulation, and land abandonment (Dax et al. 2021; MacDonald et al. 2000; Plieninger et al. 2016). Between 1961 and 2010, the number of farms in rural mountain areas of Italy declined by 75% (Spinelli & Fanfani 2012). Despite these trends, there does remain a contingent of farmers who continue to farm, joined by new farmers who have chosen to take up agriculture in the mountains (Dourian 2021; Lupi et al. 2017; Milone & Ventura 2019; Sivini & Vitale 2023). As in mountain areas across Europe, most of these remaining farms are smallholder farms (Kania et al. 2014; Spinelli & Fanfani 2012). Smallholder farms contribute to rural vitality and ecological resilience and provision important ecosystem services for both the highlands and lowlands (Beniston and Stoffel 2014; Egarter Vigl et al. 2017; Grêt-Regamey et al. 2012; Klein et al. 2019; Rivera et al. 2020). These services include tourism, water provision, support of local economies, and the protection of biodiversity and cultural and natural heritage (Bieling et al. 2014; De Groot 2010; Summers et al. 2012). Agricultural activities shape the appearance of the landscape (Höchtl et al. 2005; Niedrist et al. 2009; Plieninger et al. 2016; Schirpke et al. 2021) and the functionality and resilience of mountain ecosystems (Marini Govigli et al. 2022; Marino et al. 2022; Shucksmith and Rønningen 2011). In addition, farming is very important in the European imaginary and mountainous and rural areas across Europe are seen to contain the family farms and landscapes that sustain “not just rural society, but society as a whole characterized by the ideals of stability, justice and equality” (Demossier 2011a,b; Gray 2000:35).

Factors that detract from farmer well-being and might drive farmers to abandon agriculture, therefore, should be reduced both to promote farmer well-being, an important objective in its own right, and to ensure the persistence of mountain agriculture to the benefit both of mountain farmers and Europe as a whole (Mengist et al. 2020). While existing studies on farming in Italy have demonstrated that farmers face extensive challenges posed by the regulatory and policy context (Blasch et al. 2022; Gullino et al. 2018; Varia et al. 2021), the impact of this context on farmer well-being in Italy requires further study. The current study thus fills a need for work on how and why government policies and regulations affect farmer well-being and for studies examining the well-being of Italian farmers on the whole (Gosetti 2017; Daghagh Yazd et al. 2019).

The following sections will describe three scenarios where government policies and regulations negatively affect farmers’ well-being and will outline potential long-term implications of these scenarios for farmers. These scenarios cause farmers to experience stress, frustration, and disillusionment as well as a reduced sense of control over their work. They foster conditions of inequality and uncertainty. Some farmers have come to feel that farming is not valued by society. Potential long-term implications include a further erosion of trust in government institutions, the fostering of an us (the farmers) versus them (the state) mentality, and the further abandonment of agriculture and rural areas.

Background

Defining well-being

Well-being is a multi-dimensional concept. It has individual, interpersonal, and existential dimensions (Mathews & Izquierdo 2009). Well-being includes people’s ability to fulfill basic needs, such as the need for food and housing (Tay and Diener 2011; OECD 2015; Veenhoven 2008) or financial security (Kearney et al. 2014; Lunner Kolstrup et al. 2013; Furey et al. 2016; Logstein 2016). It also includes psychosocial needs, such as the need for respect, dignity, social connections, love, purpose, meaning, and control (Tay & Diener 2011; Veenhoven 2008; Ward & King 2017). In order to be well, an individual must feel fulfilled, feel that their life has meaning, and be free to pursue what they deem of value (Seligman 2011; Marks and Shah 2004; Ryff and Singer 2008). Control over one’s life is also important for psychological and physical well-being (Matthews & Izquierdo, 2009; Smith et al. 2000; Grob 2003; Fischer 2014; Reker et al. 1987). Feeling in control can even compensate for low income that might otherwise negatively affect health and well-being (Lachman & Weaver 1998). Lack of control, on the other hand, can lead to feelings of stress and anxiety (Mineka & Kelly 1989; Gallagher et al. 2014; Griffin et al. 2002). Feeling one’s life has dignity and is respected by society has also been shown to be important for well-being (Fischer 2014; Mathews & Izquierdo 2009) as has fulfilling social and cultural values (Diener & Suh 2003; Dressler & Bindon 2000). Conditions of insecurity and uncertainty are instead linked to worse well-being (Hadley et al. 2012; Witte 1999; Wutich & Ragsdale 2008) as is inequality, which has also been shown to decrease the social cohesion and trust known to underpin well-being (Marmot & Wilkinson 2001; Wilkinson 2006). Subordinate social status, a product of inequality, is linked to chronic activation of the stress response which can lead to stress related diseases such as high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, and coronary heart disease (Sapolsky 2004).

The majority of studies on farmer well-being have been conducted in developed countries (Daghagh Yazd et al. 2019; Kohlbeck et al. 2022; Lunner Kolstrup et al. 2013; Wheeler & Lobley 2022). Studies of farmer well-being from the United States (Brigance et al. 2018; Klingelschmidt et al. 2018; Rudolphi et al. 2020), Canada (Jones-Bitton et al. 2020), the United Kingdom (Simkin et al. 1998; Wheeler & Lobley 2022; Wheeler et al. 2023) and Ireland (Brennan et al. 2022), Scandinavia (Kallioniemi et al. 2016; Torske et al. 2016), Australia (Brew et al. 2016; Fraser et al. 2005), New Zealand (Alpass et al. 2004; Bin et al. 2008), and continental Europe (Lunner Kolstrup et al. 2013; Truchot & Andela 2018) report low levels of well-being and high levels of depression, suicide, stress, and anxiety among farmers (reviewed in Daghagh Yazd et al. 2019; Younker & Radunovich 2021; Lundqvist et al. 2023). Common stressors reported in these studies include weather and climate change, financial strain, concern about farm succession, and socio-economic inequality. Compliance with government policies and regulations, lack of government support, and globalization also cause stress. Farmers report stress linked to having insufficient time, an excessive workload, and a lack of a work-life balance. These stressors have been shown to lead to feelings of hopelessness, burnout, loneliness, lack of social support, and isolation (Bondy & Cole 2019; Lundqvist et al. 2023; Truchot & Andela 2018; Wheeler et al. 2023). Farmers also report low health-seeking behavior and stigmatization around mental health challenges (Bondy & Cole 2019; Gregoire 2002; Hull et al. 2017).

Government policies and regulations are one of the stressors that affect farmer well-being (Bin et al. 2008; Kallioniemi et al. 2011, 2016; Simkin et al. 1998; Logstein 2016; Daghagh Yazd et al. 2019). Dealing with the extensive paperwork and understanding and implementing complex regulations creates worry and anxiety (Booth and Lloyd 2000; Scheurich et al. 2021; Simkin et al. 1998; Truchot & Andela 2018). Factors influenced by government policies, and beyond farmer control, such as increasing expenses, increasing complexity and quantity of regulations, and changes to tariffs and prices, contribute to farmer stress and worry (Alpass et al. 2004; Booth and Lloyd 2000; Henning-Smith et al. 2022; Hossain et al. 2008). Keeping abreast of new legislation creates stress as does regular inspection of the farm by government officials (Alpass et al. 2004; Truchot & Andela 2018). Inspections by government officials and regulatory demands have also been shown to increase feelings of marginalization, unfairness, and loneliness among farmers (Wheeler et al. 2022).

Smallholder farmers and the agroindustrial system

Despite being located on the margins of the dominant industrial agricultural system, smallholder farmers in the mountains face pressure to increase in size, industrialize, mechanize, and integrate into international markets (Dax et al. 2021; Flury et al. 2013; Knickel et al. 2013) even though this shift towards modern industrial agriculture has not necessarily led to greater prosperity in rural areas (Rivera et al. 2018; Kinckel et al. 2013). The rise and fall of prices and the instability of agricultural markets create conditions of insecurity and uncertainty for smallholder farmers who are susceptible to shocks to the system (European Commission, DG AGRI 2018; Gray 2000; Jepsen et al. 2015; Zimmermann and Heckelei 2012).

In Europe, the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) intervenes to support farmers economically and protect against market instability (European Commission, DG AGRI 2018; Gray 2000; Papadopoulos 2015). It does so through providing farmers with direct payments based on the amount of land they work. Farmers are also able to apply for subsidies and grants based on, for example, their age, being located in a disadvantaged area, and practicing agriculture that is environmentally friendly (European Commission, DG AGRI 2018). Nonetheless, the majority of EU CAP economic support goes to industrial farms with whom small farmers must compete (Bournaris and Manos 2012; Verwoerd 2019). Even with EU support, being integrated into this larger agricultural system means that small-scale farmers operate under complex, insecure, and unstable conditions. The regulatory and policy context with which they must engage is shaped by this larger agricultural system, one dominated by industrial agriculture and large scales of production.

The regulatory and policy context of farming in rural mountain areas of Italy

The contours of Italy’s agricultural policies, programs, and regulations are defined by the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Individual Member States develop Strategic Plans for implementing the CAP that are tied to specific national conditions. Italy has an agricultural sector and agrifood system that is one of the largest in the EU in addition to being highly diverse (European Commission, DG-AGRI 2023a). The country also has an enormous range of landscapes and ecosystems each with unique needs. For example, over half of the land used for agriculture in Italy is in mountain areas or areas with natural constraints. Italy’s regulatory system and agricultural policies must therefore address the needs of a diverse – socially, culturally, economically, and ecologically – territory while adhering to EU guidelines (European Commission, DG-AGRI 2023a).

Agricultural policies and regulations are designed at high levels by technocrats. These individuals remain largely distant from the on-the-ground realities of a diverse agricultural landscape. As a result, generalizable, scientific, technical knowledge underpins policies and regulations (Macnaghten and Chilvers 2014; Scott 2008). In policy arenas, this knowledge is given primacy over other forms of knowledge including the practical, place-based knowledge born of a long history of engaging with specific landscapes and places. Modern farmers are aware of the technoscientific knowledge of current policies as they are required to follow a highly complex regulatory environment in their agricultural practice, but they also possess additional knowledge of the specific places where they farm. This place-based knowledge is constantly being updated and adapted to changing local conditions (Ingold and Kurtilla 2000; Scott 2008). While the EU is seeking to adopt a less technocratic approach to the design of regulations and policies (Bazzan and Migliorati 2020; Minotti and Zagata 2020) and the EU and individual nation states solicit feedback on the CAP from citizens, local, place-based knowledge is not often incorporated into government policies and regulations (Smallman 2018, 2020). The distance can be wide between policymakers and the citizens their policies affect.

Italy in particular has a top heavy, inefficient, and complex existing government bureaucracy (Cottarelli 2018; Fontana 2021; Herzfeld 2021). The country ranks behind nearly all other European countries on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business score (Rank of 58) above only Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Greece (World Bank 2020). It has a large public debt, high labor costs relative to other countries, a large public administration, high levels of corruption and patronage promotions, and it has been crippled by recent austerity measures (Cottarelli 2018; Del Monte and Papagni 2001; Golden 2003). For a small or medium sized business, the cost of dealing with bureaucratic requirements imposed by the Italian government is 45 to 190 full time working days (Assolombarda 2017 in Fontana 2021). The burden of bureaucracy has been increasing over time and is greater on smaller companies who may not have the employees to dedicate to handling bureaucratic requirements (Fontana 2021). While Italy’s economy remains one of the largest in Europe, it has been in decline for decades (Cottarelli 2018). Italians have long reported high levels of dissatisfaction with the government and its bureaucracy (Golden 2003; Morlino and Tarchi 1996; Torcal and Montero 2006). The complexity, inefficiency, and burden on farmers of Italy’s bureaucracy make it an interesting place to study the interactions between government and the well-being of farmers.

Methods

The setting: the Lombardy Alps and the Garfagnana Apennines

Interviews and participant observation were conducted with small-scale farmers in two rural mountain areas of Italy: the Alps of the Lombardy region and an area called Garfagnana in the Apennine mountains of northern Tuscany. The first set of interviews and participant observation were conducted in the Val Camonica and Valtellina of the Lombardy region Alps between December 2017 and December 2018 and between June 2019 and August 2019. Interviews and participant observation were conducted in Garfagnana, Tuscany between July 2021 and July 2023.

The Val Camonica and Valtellina are the two largest valleys of the Lombardy region Alps. Most informants lived in the Val Camonica, a 90-km-long valley that extends from the Lago d’Iseo to the Passo del Tonale (1883 m) and has a population of 100,161 inhabitants (as of 2019). At its widest point, the valley is about two kilometers across the bottom; at its narrowest, just a couple hundred meters. The valley is flanked by national and regional parks. The Valtellina runs adjacent to the Val Camonica. The entire valley is 120 km long running from the Lago di Como to the Passo dello Stelvio (2758 m). Like the Val Camonica, the Valtellina is flanked by mountains that reach over 3500 m in elevation. Towns dot the length of both valleys. Most of the towns are in the valley bottoms but can also be found several hundred meters up the mountainsides. Off of the main valleys extend inhabited lateral valleys that are smaller and narrower. In recent decades, forests have taken over many former agricultural fields, but the pastures, fields, terraces, and grazing livestock that remain give the valleys a traditional European Alpine appearance. At the same time, in recent decades, the valley bottoms, once used primarily for agriculture, have become occupied by warehouses, factories, and housing.

Garfagnana is an area of northwest Tuscany located between the Apennine mountains and the Apuan Alps, with the highest peaks around 2000 m in elevation. The landscape is defined by mountains and almost entirely lacks a valley bottom. It is one of the rainiest areas in Italy and is densely forested, including by the chestnut trees for which it is well-known. To the west lies the Regional Park of the Apuan Alps and to the east the National Park of the Tosco-Emiliano Apennines. Like in the Alps, agriculture used to be a dominant economic activity, but has been widely abandoned since the 1960s (Spinelli & Fanfani 2012). As an indication of the limited agricultural activity left in Garfagnana, there are only six remaining dairy farmers who sell their milk to large milk cooperatives.

The number of farms located in mountain areas in Italy decreased from 1,086,000 in 1961 to 275,000 in 2010, a decrease of nearly 75% (Spinelli & Fanfani 2012, based on the 2010 Italian Agricultural Census). The abandonment of agriculture has led to widespread reforestation and the transition of many agricultural fields into forested areas. The agriculture that remains is primarily small-scale, family farming largely for personal consumption or local sale.

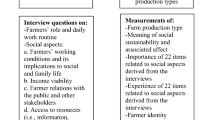

Interviews and participant observation

The majority of studies on farmer well-being are based on quantitative survey data (Daghagh Yazd et al. 2019). This study instead draws on qualitative interview data and participant observation to explain how and why government policies and regulations reduce farmer well-being. The current study is a subset of a larger project on the impact of climate and environmental changes on agriculture and farmer well-being in mountain areas. Semi-structured interviews were therefore aimed at understanding the nature of agriculture in the areas of study, the primary challenges and opportunities facing farmers and beekeepers, their experiences of environmental and climate change, and the impact of recent social and ecological changes on farmers’ sense of well-being. Importantly, the ethnographic approach of semi-structured interviews and participant observation allowed issues to emerge that were not the primary focus of the original research study, including farmer emotional responses to agricultural policies and regulations. The issue surfaced organically; the frequency with which it was mentioned meant it could not be ignored.

People’s behavior does not always match statements made in interviews and the process of being interviewed can shape informant statements (Bernard et al. 2013). Participant observation therefore allowed for validation of the data collected in interviews. Field notes were taken during and after participant observation (Bernard 2013; Spradley 2016). The use of interviews, participant observation, and extended fieldwork (Bernard 2013) gave informants the space to talk about meaning, values, and emotions, about what makes them well (Camfield et al. 2009). Participation in the daily lives of informants also revealed the role of the social and cultural context in shaping well-being (Camfield et al. 2009; White and Pettit 2007).

Farmers raise livestock and /or grow crops. All combine traditional agricultural methods or crops with modern techniques. Beekeepers include both hobby and professional beekeepers. All those interviewed are all small-scale farmers who farm with the goal of making a living (Halloway 2002), though not all are dependent on farming for a living. The beekeepers interviewed also seek to make income from their beekeeping but for none of the beekeepers is beekeeping their sole economic activity. Farmers often engaged in off-farm work. For each of the beekeepers and farmers, producing for their own consumption was an important part of their agricultural activity (as found for other farmers, see Wilbur 2014).

Semi-structured interviews were completed with 44 small-scale farmers and 23 beekeepers in the Lombardy region of the Italian Alps (26 [38.8%] women, 41 [61.2%] men; age range 27 to 82, average age: 47) and 34 small-scale farmers and 3 beekeepers in Garfagnana (28 [75.7%] men and 9 [24.3%] women; age range: 22 to 72, average age: 51 years) (Table 1). Informants were identified through local agriculture websites (Val Camonica and Valtellina), through snowball sampling, and through farmer databases (Bernard et al., 2013). Saturation is typically reached after interviews with thirty informants (Francis et al. 2010). Interviews ran from one to three hours depending on the farmer. Some interviews began at a kitchen table and ended with a tour of the farm. Eighteen interviews were recorded, the remaining were not recorded.

Between 2017 and 2023, repeated participant observation was conducted with farmers and beekeepers. This participant observation included making hay, milking animals, making cheese, and caring for bees. The researcher also spoke with local residents about agriculture and attended local agricultural and community events.

Textual data from interviews and participant observation was coded in the textual analysis software MAXQDA and in Microsoft Word. Both thematic analysis and inductive and deductive coding were used (Bernard et al. 2016). As the interviews covered a number of topics, deductive coding uncovered the sections of the interview where informants spoke of government and bureaucracy. Deductive codes included: government and bureaucracy with subcodes for, for example, funding schemes, government health authority, organic certification, economic factors, return to the land, mountain difficulties/opportunities, and traditional knowledge/methods. Once the areas where farmers spoke about government and bureaucracy were identified, the extracted sections were then analyzed for emotion words. Inductive codes included emotion words such as worry, concern, and frustration as well as well-being words such control, unpredictability, and uncertainty. Emotion words had arisen naturally throughout the interview (e.g. du Bray et al. 2022). The themes that emerged form the core of the three scenarios outlined below and the identified pathways through which these scenarios affect well-being. Speaker voice and tone were also taken into consideration (Cunsolo-Willox et al. 2012; Bernard 2013).

All interviews and participant observation were conducted in Italian directly by the researcher. Relevant quotes were translated into English. All informants have been given pseudonyms. Age and gender are listed in parentheses after quotes (for example: 31W = 31-year-old woman). Informed consent was obtained from participants and the research study was approved by an Institutional Review Board (for human subjects research).

Results

Farmer emotional well-being is affected when policies, programs, and regulations designed by regional, national, and European Union government entities are implemented in rural mountain areas. Three types of scenarios that had negative effects on farmer well-being arose frequently. Farmer well-being is affected (1) when a regulatory system seemingly designed for industrial agricultural operations in lowland areas meets the realities of small-scale mountain farming; (2) when farmers and beekeepers seek to access and use government subsidies and grants; and (3) when the techno-scientific knowledge system that underpins government policies and regulations conflicts with local, place-based knowledge. After outlining the three scenarios, the article discusses how and why they affect well-being (Table 2). Of less concern are the specific content of the policies, programs, and regulations. Farmer perceptions and responses are instead the focus.

A mismatch between contexts: lowlands versus highlands

When policies designed for the lowlands are applied in the highlands

Two examples serve to highlight what happens when regulations that seem designed for intensive agricultural operations in the lowlands are applied to mountain farms. “You’re supposed to use a different wipe to clean each goat [before milking],” Eleonora explained. It was 5:30 in the morning. Despite being mid-August, it was biting cold. Eleonora explained that the official rule is that a farmer must use a fresh disinfecting wipe to clean any dirt or feces off the goat’s teat before milking. The wipes are meant to keep the milk from becoming contaminated, though Eleonora explained that the milk is also filtered in the process of making cheese. Eleonora has 80 goats. Milked twice a day, this would mean she would need 160 wipes a day. Just over the three months of summer when milk production is at its peak, she would need 14,400 wipes, or about 300 packages of wipes.

Eleonora’s summer farm is located at 2000 m in the heart of the Lombardy Alps. The farm is accessible only by helicopter or a one hour hike up an old military trail. Once a week, Eleonora can use an old cableway to transfer supplies up and down the hill, but just to get to the base of the cableway is a twenty-minute drive up a winding road from the nearest town, a town of 1000 inhabitants. It is a two-and-a-half-hour drive from the nearest big city. It might be feasible for a farm located in the lowlands near to stores and warehouses to use a new wipe for every goat. The rule may also be necessary in the lowland intensive farms where the animals live in close quarters and where the risk of disease transmission is high. But, Eleonora explained, her goats spend their days and nights outside in the fresh air with plenty of space for every animal. She does not think it makes sense to use a new wipe for every goat. To her, the risk seems low, the benefit minimal, and the economic and labor cost high. While the regulations governing hygiene in lowland intensive farms and small mountain farms are the same, the context is different. A young farmer in Garfagnana expressed a similar sentiment to Eleonora, “We’ve been basically swallowed up by the industrial farms … at the level of laws and ordinances, we’re all treated the same. There is not anything more specific for the small producer” (22F). Her farm, too, is located distant from urban centers.

This disconnect between highlands and lowlands can affect new farmers seeking to open an agricultural activity in the mountains. Two young farmers found a piece of land for their farm located at the end of a small dirt road in the middle of the forest in Garfagnana. Every cement mixture used in the construction of the farm buildings had to be certified by an official authority. In such a situation, ideally, a farmer would get a cement truck to deliver a large batch of certified cement. The problem these particular farmers faced, though, was that the road leading to their land was too small for a large cement truck. Therefore, they had to mix individual, small portions of cement, and then drive a sample from every batch to the nearest large city, an hour’s drive away, to have the cement certified. The mountain environment and the rural location made the—though perhaps well-intentioned regulations—impractical.

In both examples, regulations seem to be unaware of the constraints imposed by the steep terrain and relative isolation of mountain areas. While farmers acknowledged that the regulations might make sense for intensive operations in the lowlands, and may even be backed up by research, the regulations need to be modified for small-scale operations in high-mountain areas. An agritourism owner in Garfagnana summarized farmer attitudes:

“They take away the passion of the smallholder … because in the moment when a shepherd who has 80 animals … has to submit to the same regulations as does an industrial dairy producer and spends all day filling out [forms] losing lots of time … Things must be controlled, but there also needs to be a moment of understanding … otherwise you just can’t manage it, and this is why things are going lost.”

Or, in the words of another farmer: “They take the regulations made for the big farms and they pass them on to the small farms and so the small farms have disappeared.” When regulations do not make sense for the mountain context, but nonetheless must be implemented or farmers will be fined, farmers experience frustration, stress, and disillusionment.

The disconnect between the realities of farming and the places where policies are made

Farmer well-being is also affected when regulations are implemented and situations result where there is a clear disconnect between the realities of farming and the places where regulations are made. As a livestock farmer said, “The rules do not make sense for the realities of small mountain farming”. Two examples highlight this farmer’s point. The first is about opening a farm in the mountains and the second about obtaining the organic certification.

An organic vegetable farmer in her late 30s, expressing disbelief about the issue years later, describes the challenges she faced in finding land as a new farmer. She explained that in order to qualify for subsidies to open her farm, she had to find land that was already actively being used as farmland, “worked in a certain way, with certain crops … That is, you can’t just open a farm on any land and begin, no! The farm already had to exist in order for me to open it. I mean, really, it’s as if everyone, and here we return to the Lombardy Region – the state does not understand anything – we should all be children of farmers.” The European Commission has identified accessing land as one of the primary barriers to new entry into farming (EIP-Agri 2016). While there are diverse structural issues at play determining access to land, the regulations encountered by this farmer adds another layer of complication. When such a situation results, it can discourage people from pursuing agriculture at all. Those who do continue may experience frustration and stress, as well as disillusionment.

The second example regards obtaining the organic certification. Marco, a beekeeper and farmer, describes his experience with the certification process:

“You spend hours filling out paperwork and keeping track of everything. Then, once a year someone comes and inspects that you’re doing everything right. They come, sit in your kitchen for six or seven hours, print a million papers and then make you fill out all the same stuff online. I once asked the inspector why I have to print it if it’s all online and he said, ‘that’s just the way things have to be done. You have to print it all too.’ Only the very first check did they come and assess the soil and check the actual farm. All the other times, they just came and checked the paperwork.”

On one visit, the inspector told Marco that he could not keep his blueberries in planters above the ground. Marco had used planters because the soil on his farm is not sufficiently acidic for the berries. He retrieved the soil from a nearby forest. He asked the inspector, “so if I dug a hole and put the berries – planters and all – in the ground, that would be ok?” The inspector replied, “yes, because they would be in the ground.” Marco concluded, “I do not have much faith in the certification anymore.” He has since decided to give up the organic label: “My customers know how I work … I do not really need it.”

Even with the best of intentions, adhering to the complex government regulations is not always possible. But, the risk of non-compliance is high. Keeping up with and following all the government regulations could bankrupt a farmer, but not doing so comes with potential financial repercussions. Fines can be devastating, especially for small farms. As a livestock farmer in Garfagnana explains:

“You forget to write in your registry one animal, but it has its ear tag [meaning it has been registered] and you get fined. Not a 30 Euro fine but a 1000 2000 3000 Euro fine even for absurd things. No, they [the government] don’t help you … and then maybe they don’t go do an inspection in the places where it is really needed. They come to you, tell you everything is ok, but then give you a fine for the tiniest thing” (22F).

She explained how her small farm is compared to an industrial farm, but the incomes are vastly different. Importantly, though, farmers do want to follow the regulations, and think that there need to be regulations. The statement, “it is just that there are rules,” came up repeatedly. A cattle and pig farmer in Garfagnana explained his relationship with the local veterinary health authority: “I’ve always said, ‘if something isn’t right, tell me.’ At least that way we can find a solution” (28M). But, another adds, “Let’s just hope the system changes. We continue our work, but it’s a struggle” (53M).

When regulations are implemented in the mountains, it can become clear that they were designed far from the everyday realities of mountain farming. Regulations may make sense for industrial operations in lowland areas, but less sense for farms located thousands of meters up a mountainside. The situations that result when these regulations are implemented can cause frustration and disillusionment, sow doubt in government policies, and have implications for farm management, as will be discussed further below.

A disconnect between the goals of subsidies and the reality of their implementation

Obtaining and using government subsidies and grants

The Italian government and the EU make available subsidies and grants for agricultural activities in the mountains. The stated goals of these subsidies vary. Some are to support farmers in general, such as the direct payments program; others have specific objectives in mind, for example preserving a particular crop or animal species, protecting a unique landscape, supporting the construction of agricultural infrastructure, or assisting young farmers to launch their farm. A series of examples illustrate how obtaining and using government funding can lead to frustrating and stressful scenarios.

A small mistake in the endless and complex paperwork required to obtain funding can cost a farmer dearly. A 31-year-old beekeeper and viticulturalists from the Alps had the following to say, “The bureaucracy does not help you, especially if you try to do anything out of the ordinary … we lost some subsidies as a result. It’s something that weighs on me.” Farmers explained that while a large farm or organization of farms, more common in lowland areas, might be able to afford to hire an expert to complete the paperwork for them, a small-scale farmer may not have the finances, the knowledge, or the time to handle the application process. A livestock farmer in his early 40s said, “There are certainly organizations that are good at getting funds because they are capable of filling out the forms … the problem is that they make it impossible for you [an individual farmer] to access the funds.” Or, as another farmer explained, “It’s complicated to get [the subsidies] … people who have only one or two people working for the farm – they have to take care of the animals and perhaps they pass all their time in the barn – they don’t have time to also think about all the documentation they have to provide.”

A new livestock farmer in her late 30s described the hassle of obtaining financial support for the construction of a stall. In order to access the grant money, the local municipality had to re-classify her land from business to agricultural. The town has a population of less than 1000. Nonetheless, it took more than six months for the local government to approve the classification change. In the meantime, she won the subsidies, but the deadline to claim them passed before the municipality approved the classification change. In the end, she took out a mortgage to build the stall. She is managing, but the process caused much frustration and made her question whether there was local support for her activity. A farmer from Garfagnana described similar challenges: “Now there is so much bureaucracy so if you want to make a new fence or even fix an old fence it’s a problem. You have to have all the permissions and to get them it takes forever. It’s very hard, especially at the bureaucratic level” (28M).

Those who successfully secure grants or subsidies speak of an endless mountain of paperwork and constant surveillance, and of regulations that do not seem to make sense for small, multifunctional mountain farms. For example, once government funding is obtained, the way it has to be used is highly regulated. While this is important to reduce corruption, the requirements sometimes conflict with how a farmer might have used the financing if allowed to manage it on their own. A young goat farmer explained that, as part of the requirements of a grant he won, he had to spend 30,000 Euros on agricultural machines. He bought a tractor, but, he said, he did not need to spend all that money on a new tractor. He could easily have spent closer to 5000 Euros on a small, used tractor and used the remainder on items he needed more. He argued that if the well-being of the farmer and the future of the farm were really of top concern, then the government would have let him spend the grant in a different way. To him, it seemed clear that the main goal was, even if only in a small way, to contribute to stimulating the wider economy rather than actually promoting his farm. He felt used even if he was also very grateful to have won the grant.

A young organic vegetable farmer explains how she feels about the EU CAP subsidies she received to start her farm. Individual countries in the EU can choose to designate a portion of the funds they receive to support young farmers, for example by providing farmers under 40 with start-up funds (European Commission DG-AGRI 2023b). Frustration and irritation as well as a sense of resignation and disillusionment come through in her discussion of the reporting requirements of the grant.

“And then you have so many forms to fill out … I have ten square meters here and I have to record everything I have planted. But if in a week I pull up the beets and then I put in lettuce, how can I record all this? And how can I possibly know how much I’ll make in a year when everything changes so much? That is, if this year goes well, I’ll make a certain amount, but next year it is logical that things will be different … I’m always changing things. Are you saying that every time I change what I am planting I have to tell them and pay 50 euros? Every six months I change things, and I have to tell them everything? You have got to be kidding. For five years, though, I have to do it.

Since then, I have not requested any grants or subsidies … and, I’ll tell you, I already regret getting the ones I did, it would have been quicker to do nothing, because it is all a terrible headache from a bureaucratic perspective.”

While the reporting requirements might make sense for monoculture agricultural operations, they do not make sense for the type of agriculture that is common in the mountains, one that is multifunctional and constantly changing. The above examples beg the question of the value of grants and subsidies if the barriers to access are so high and if the grants and subsidies are so complicated and frustrating to obtain and manage.

Subsidies shape agricultural practices, sometimes in unintended ways

Some subsidies or grants are designed to support specific types of agriculture. In so doing, they shape the type of agriculture practiced in the mountains. A viticulturalist in his mid-50s explains: “The [local government agency] will give a farmer subsidies if they grow a certain type of grape—Merlot, Marsemino, and Cabernet—but not other types.” Farmers respond by growing these varieties, he explained, but the result could be the loss of unique, local varieties. On the other hand, some subsidies do encourage farmers to raise breeds that might otherwise disappear, such as autochthonous breeds of sheep, like the pecora di Corteno, a local breed of sheep unique to the town of Corteno Golgi (population ~ 1900) in the Val Camonica or the white Garfagnina sheep and the Garfagnina cow, breeds unique to Garfagnana. In so doing, the subsidies support the preservation of biodiversity, as well as the traditions that accompany the raising of animals, such as outdoor pasturing and the making of traditional products. These traditions might otherwise go lost, with downstream effects on society and the environment.

Sometimes, though, the economic support has unintended outcomes. The following example is presented in detail as it captures the many dimensions and implications of a specific subsidy program. An unfortunate side effect of the allocation of European funds to farmers who pasture animals at high elevation is that speculators and people who live outside of the mountains vie with local farmers for access to the high elevation pastures (malghe). The malghe are highly sought after because they are an important source of pasture for animals; the cheese and butter produced in the malghe is of high quality and is in high demand; and farmers receive significant EU subsidies for moving their animals to the malghe in the summer.

The malghe are run by local municipalities who rent them out, at least historically, to local farmers. Recently, though, large, wealthy farms, or speculators, located distant from the mountains are winning the contracts because they can offer rents that are out of reach for mountain farmers. Two livestock farmers explained what has happened to a malga near theirs: “That malga has fallen into the hands of people from far away who can offer a lot of money for it … They want the malga because they get subsidies from the state for maintaining it.” The farmers continued, “We almost lost our malga to a farm from away, but the other person who made the claim did not end up showing up … We have a friend who was unable to get a malga because they could not afford the high rent … Malghe are going for 12,000 Euros, something a small farmer cannot afford.” For municipalities strapped for cash, the higher rents are a boon, but the awarding of contracts to non-local farmers comes with consequences for local farmers and for landscapes and ecosystems.

Ludovico, a livestock farmer in his early 40s, explains that he did not get the contract for his local malga, and the different reasons it is a problem if the malghe are not used.

“Normally, the local government considers the applications and tries to favor people from nearby … Instead, the mayor chose someone from away who would pay 21,000 Euros a year to the town to have the malga, whereas the rent before had been closer to 5000 to 6000 Euros. I was willing to pay a bit more than that, but not 21,000 … This guy didn’t even end up coming to work the land …

With a longer term vision in mind, the municipality could have thought about how this person might not even come up and work the land and that the trees might grow up as a result and therefore the value of the land would go down with time so that by the time the next person comes to rent, the malga would have less pasture and be worth less and the municipality would lose money …

If they rented it to someone who they knew would go up there, they would at least not lose money because the size of the malga wouldn’t decrease and might even increase and they would be investing in local community and people … The municipality invested in money and not in people … This kind of situation should not exist. The malghe should not be rented just based on economic reasons to a farm who has nothing to do with the land, who maybe later you find is just a speculator.”

The livestock farmers affected by the non-local competition for the malghe are very frustrated: “It is a big problem for the people of the place and is just not right” (early 40s, M). Luckily for some local farmers, not all malghe are managed in the same way. Certain municipalities fix the rents on their malghe and local farmers are prioritized. A livestock farmer in her 30s explains, “We pay 3500 Euros for the malga but other malghe, like the one up the hill [belonging to a different municipality], go for 15,000.”

These sorts of situations make some farmers question whether the government is really looking out for them, or if it has other motivations and mountain areas are just being used:

“That’s just the way things are. The wealthy politicians design policies that ultimately help them. There are policies in the CAP for mountain areas, but in the end, they don’t help mountain areas because the politicians support the large farms in the lowlands and they know they can get the money that is supposed to be for the mountains by applying and offering a lot for the malghe, more than anyone from here can afford (late 30s,M).”

This farmer had detailed knowledge of the CAP, but was unimpressed by its policies, even those that were supposed to favor mountain areas, “The money ends up going to the rich large farmers in the lowlands no matter what. Probably these farmers are friends with the politicians … Politicians can appear to be supporting small, mountain farmers, but instead they are just benefiting themselves as usual.” A young farmer in Garfagnana made an argument along the same lines: “We took the exam for the professional agricultural entrepreneur and they talked about mountain areas as disadvantaged areas, but in the end the promised support never arrives. They talk to you about it, they say, ‘yes, these areas are disadvantaged,’ but when it comes down to it, there is not any support.”

This is not to say that farmers do not benefit from government subsidies. As one livestock farmer put it, “finished the subsidies, finished mountain agriculture.” Another livestock farmer and forester explained, “I opened my farm three years ago, but only started selling now. It was a long process. In fact, without grants, I would never have made it.”

While the subsidies are, at least in theory, meant to assist small-scale farmers, and sometimes they do, farmers nonetheless face hurdles accessing, using, and managing the funding. The complexity of the funding process, the barriers to accessing the grants, and the reality of their implementation mean that the grants and subsidies do not always achieve their intended results. In fact, the way they are implemented can have the opposite effect, cause frustration and stress, as well as disillusionment with the government, and have real implications for farm economy.

Disconnect between scientific and local knowledge

The final scenario comes about when a knowledge system rooted in techno-scientific understandings of agriculture encounters local, place-based knowledge, the knowledge systems conflict, and it becomes clear which knowledge system is considered of higher value. Many farmers will agree that some of the government regulations do make sense. There need to be regulations about how to keep things sanitary, to safeguard animal welfare, and to protect farmers and consumers. But when regulations designed in one knowledge system are imposed on another, the disconnect between them is laid bare. This disconnect results in situations that undermine, perhaps unintentionally, knowledge derived from daily contact with animals and environments and passed generation to generation. The disconnect can affect well-being by making farmers feel their knowledge and contribution is not respected or valued.

This disconnect can take different forms. For example, regulations rooted in technoscientific knowledge may apply well to highly controlled and controllable industrial agriculture settings in lowland areas, such as intensive, indoor cattle farms. These same regulations may not map on to settings where less control over animals is possible, such as mountain areas where animals are pastured in the wild and are milked at outdoor, transportable milking stations in high elevation pastures. Outdoor, small-scale, mountain farms, may require regulations that better harmonize both technoscientific knowledge as well as local, place-based knowledge.

Regulations may contradict farmer understandings of proper land management. For example, for decades, the forest service’s policy was to protect fir trees in order to encourage reforestation. Farmers and foresters had to obtain permission from the government to cut down the trees. This rule, combined with the on-going process of rural abandonment, allowed fir trees to expand widely into pastures and fields and to higher elevations. Farmers argued that the policy should never have been in place. They should have been allowed to cut the trees. Now, the policy has changed. Fir trees may be cut down, but other species of trees are protected. The flipflopping rules are confusing and frustrating to some farmers who have seen the negative impact of these policies on their agricultural practices. The question here is not whose knowledge is correct, but that one is given priority and imposed on the other.

As another example, regulations may not align with traditional agricultural practices and this disconnect may cause farmers to evade the regulations. For example, government regulations require cheese and meat products (such as salami) to be aged in a specialized refrigerator cell that electronically maintains a constant temperature and can be completely disinfected. But, some farmers argued, the meat and cheese aged in these cells does not taste as good or as authentic – and is not what their customers expect – as products aged in traditional cellars. Traditional cellars are dark, may have dirt floors, and would be difficult to keep as sterile as a refrigerator cell. The farmers insist, though, that the temperature stays constant in these cellars too, and thus food safety is not an issue, and that the product emerges of higher quality. Therefore, some farmers continue to use traditional cellars, even when they have a refrigerator cell on hand.

The disconnect between knowledge systems also emerges when the implementation of government measures wrests farm management from farmers. Certain subsidies/grants require farmers to use agricultural cooperatives to complete the work subsidized by the grant. For example, if a farmer wins a grant to fence their pastures against wolves, they must hire a cooperative to build the fence. The farmer is not allowed to do work they may be capable of doing, in fact the very work of a farmer. Farmers explained that, by requiring the use of a third party, the government disvalues farmer knowledge, skills, and experience. Farmers are given the impression that they cannot be trusted to follow the requirements of the grants and that they are not capable of managing their own farm. While requiring the use of cooperatives is an attempt to support the local economy, to ensure adherence to the grant requirements, and to reduce fraud, it can come at the expense of farmers. As a consequence, some farmers choose not to apply for subsidies, which can result in lost opportunities for improving their farm.

The clash between knowledge systems can also have implications for farm management. In the following example, we see that both knowledge systems are aiming for high animal welfare, but there are different ideas about how it should be achieved. The example also shows how the realities of mountain farming, its limits and possibilities, may not made it to the places where policies are made. And, it shows how the implementation of government requirements sometimes forces farmers to ignore their own knowledge. An experienced livestock farmer in her early 70s describes her experience:

“The environmentalists and doctors who have never even been on a farm and do not know what it’s like to manage animals, they go too far … They especially do not know what it’s like to have a mountain farm … There is a new rule that the calves cannot be tied up in the stall, that they have to have their own box. The way old stalls are made, though, they aren’t set up to have a box for the calves … Plus, if you let a calf loose from birth, it’s nearly impossible to manage it later in life. It becomes wild.”

She described a case where she and her family were trying and trying to catch a calf that had never been tied up in order to give the animal a required vaccine. The veterinarian had arrived, and the vaccine had to be delivered in that moment. The animal was so agitated that it was trying to run up the walls of the stall, which put strain on its heart. She asked,

“How is that better for the calf? … They [the scientists] don’t understand what it’s like to have an animal … You can’t control the animal later on in life if it hasn’t been tied up when it’s little … The local veterinarians agree with me. When they must give a calf a shot and it hasn’t been tied up, they can’t catch the animal. It is dangerous for the animal and for the vet … I’d like to see the scientist who made the rule come up and try and catch the animal to give it the vaccine.”

The latter example is complicated because animal welfare is at stake, but the key point to take from the example is the sentiment that comes through: the farmer perceives that her knowledge is of lower value.

Tensions may arise in these situations. Farmers follow the government directives; they know they must, and they recognize the value of many of the regulations. But doing so sometimes requires them to ignore their own experience, their own knowledge, and their own understandings, with implications for their well-being.

Finally, the perception that local knowledge systems and values are not being respected also comes out in farmer statements about the value of mountain farming to society. Farmers explained how they keep the pastures and fields open, maintain traditions important for natural and cultural heritage, and contribute to preserving and protecting mountain ecosystems. Yet when regulations seem not to be designed for mountain farms or when one knowledge system seems to take priority over another, one result is that farmers feel their work and knowledge is not valued. Ludovico, the livestock farmer introduced above, explains:

“Our work is socially useful, but it is not treated as such. More dignity needs to be given by society to farming … The law and politics also need to give the work more dignity. It needs to be seen as work that contributes to society.”

An organic crop farmer in his early 60s agrees with Ludovico: “Farming has to be part of the social fabric … it needs to be supported [by mountain residents and the government].” A young livestock farmer from Garfagnana expressed a similar opinion, “Politics ignore the small producer … there is no one representing us, not locally or at higher levels … what kind of message does this send to farmers?”.

In each of the above scenarios, farmers are made to feel their knowledge, values, and contributions are of lesser value than the technoscientific knowledge that underpins government policies. Farmers are sometimes forced to implement measures that may go against their own knowledge and value systems, which can affect their sense of well-being, reducing their sense of control over their work and giving them the impression that their work does not have dignity or value for society.

Discussion

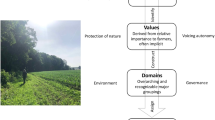

We have seen that farmer well-being is negatively affected when policies and programs designed with lowland areas in mind are applied in mountain areas, when farmers seek to obtain and use government subsidies and grants, and when regulations rooted in techno-scientific knowledge conflict with local, place-based knowledge. Not one farmer spoke only positively of their experiences with government measures. This is not to say that farmers do not also depend on government support, but what is clear is that farmer subjective well-being is affected by the regulatory context. In what way is farmer well-being affected and what are the long-term implications of these effects on well-being (Fig. 1)?

Frustration, stress, irritation, and disillusionment result from the complexity of the regulations, the times when they result in what farmers consider absurd outcomes, and the high economic stakes of failing to properly adhere to the rules. Regulations that do not make sense to mountain farmers in turn risk not being followed.

Well-being is also affected when farmers lose a sense of control over their work. This includes control over their agricultural practices and farm management, their financial security, and their ability to plan for the future. For farmers, autonomy and control are valued and contribute to well-being (Knickel et al. 2018; Rivera et al. 2018; McCarthy et al. 2023). It is important to recognize that farming is a profession in which many factors, such as unpredictable weather, changes in the social and political framework governing farming, and disease outbreaks, are inherently out of a farmer’s control, (Lunner Kolstrup et al. 2013). If autonomy and control could be increased in farmer lives, this might compensate for those situations that farmers are unable to control. Currently, government bureaucracy is having the opposite effect.

The scenarios presented can create situations of inequality, uncertainty, and unpredictability that affect well-being (Kawachi & Kennedy 1997, 1999; Marmot and Wilkinson, 2001; Wutich & Ragsdale 2008). Constantly changing regulations and lack of consistency and clarity in their implementation create situations of uncertainty. The affording of contracts to those who can pay higher rents places local farmers in a subordinate position compared to wealthy farmers or speculators. Inequality can create feelings of relative deprivation, or the perception of being worse off than those around you, which has been linked to worse health outcomes (Kawachi & Kennedy 1997). Other psychosocial effects of inequality include feelings of limited control over life, anxiety, insecurity, depression, and fewer social affiliations (Marmot and Wilkinson 2001; Sapolsky 2004). By increasing inequality and perceptions of inequality, such as between farmers in lowland and highland areas, government policies can undermine farmer well-being.

Past studies have shown that farmer subjective well-being and quality of life is tied to the feeling that their work is important for society (McCarthy et al. 2023; Mzoughi 2014; Piccoli 2020; Röös et al. 2019) and a sense of dignity is known to contribute to well-being (Diener & Suh, 2003; Fischer 2014; Mathews & Izquierdo 2009). In interviews, farmers and beekeepers spoke of the value of their work for the mountains. They help maintain and protect ecosystems and landscapes and they preserve and protect natural and cultural heritage. When malghe are awarded to farmers who do not use them and who do not even live in the mountains, the contribution of local mountain farmers not only goes unrecognized, but farmers come to see their work as not valued by society. Government actions that unintentionally devalue or disregard farmer contributions to society and the environment, or that reduce the dignity afforded the farming profession, can undermine well-being. These actions also risk increasing distrust in institutions, institutions that are there, in theory, to protect consumers, producers, animals, and the environment and to support mountain agriculture. As we have seen, the sentiment expressed by many farmers is that the state has forgotten about small-scale farmers in the mountains, that it is more concerned with the larger, wealthier farms in the lowlands.

Some farmers expressed frustration, but also hopelessness, at regulations based in a knowledge system that both feels distant from the realities of mountain farming and does not appear to incorporate local, place-based knowledge. Farmer knowledge derives from daily contact with animals and plants and with local weather and environmental conditions. Some farmers have come to feel that their knowledge is seen as inferior to that of researchers or policymakers. The perceived lack of respect furthers the divide between us, the farmers, and them, the policymakers, scientists, and politicians making decisions that affect farmers deeply, but making them far from the realities of mountain farming. It is well-established that feelings of not being treated equally erode social cohesion and trust and reduce health and well-being (Marmot and Wilkinson 2001; Wilkinson 2006). If farmer knowledge systems are not reflected in regulations, this may continue to erode trust in institutions, trust which is already low in Italy (see Herzfeld 2021; Nye et al. 1997; Scott 2008; Torcal and Montero 2006).

At the same time, it is important to again acknowledge that subsidies, grants, and low-interest loans are an important source of economic support for existing and new farmers and that they make it possible for farmers to continue to farm in the mountains. Yet knowing that the financing is there, that some people are benefiting, but that you are not, or feeling that the funding schemes were not really designed with you in mind, may create additional frustration and stress for farmers.

Conclusion

The practical implications: the future of farming, rural abandonment, and the impact on the environment

Supporting farmer well-being is a key goal of sustainable development. Dealing with government regulations and policies is an important source of stress for farmers in developed countries across the world (i.e. Daghagh Yazd et al.; Fraser et al. 2005; Lunner Kolstrup et al. 2013). Identifying the pathways through which the government regulatory context causes stress and frustration for farmers is a first step in creating conditions that foster farmer well-being.

There are important practical and policy implications of the negative impact of the current regulatory context on farmer well-being. The bureaucratic hurdles that accompany each of the forms of financial support may preclude certain farmers from accessing the funds, in so doing affecting a farm’s possibilities and even survival. Misuse of the subsidies for pasturing animals at high elevations means that pastures are not maintained, which has long-term implications for landscapes, ecosystems, and the future of farming. If the scenarios presented here contribute to driving farmers out of agriculture, this will lead to further rural abandonment and further landscape change associated with rural abandonment. Pastures and fields will continue to be overtaken by trees and cultural landscapes, such as terraces, will continue to disappear. Ecosystem services provided by farmers, such as the clearing of debris from streams and riverbeds as well as the forest floor, will be lost.

Innovation and progress may be thwarted if farmers fear acting in ways that could be fined or choose not to apply for grants or subsidies because of the requirements of the funding. Farmers may decide to not innovate on their farm because of the hassles of applying for subsidies or implementing complex and changing regulations. For example, we have seen how some farmers are discouraged from obtaining the organic certification because of the way it is regulated, and the complexity associated with obtaining the label. New farmers who wish to begin farming in the mountains may be discouraged from starting an activity by the complexity of the bureaucracy associated with starting a farm and the risks associated with failing to follow the regulations.

While there are many push factors that might cause a farmer to abandon their agricultural activities (Burchfield et al. 2022; Dax et al. 2021; Lasanta et al. 2017; Rissing 2019), the fact that dealing with government bureaucracy was mentioned by every farmer suggests that complying with the bureaucratic requirements is a burden for all farmers and may be an important push factor. Despite these push factors, most of the farmers interviewed wish to continue farming. How might they be supported?

Policy implications

The scenarios outlined above point to deep-seated structural and social forces shaping mountain agriculture that should be further analyzed and scrutinized with an eye towards reducing their impact on farmer well-being. Among other things, these forces include a global industrial agricultural system that favors mechanization and large-scale production (Jepsen et al. 2015; McMichael 1994; Van Der Ploeg 2010), the abandonment and consolidation of agriculture (Dax et al. 2021; Jepsen et al. 2015; Knickel et al. 2013), a political context where smallholder agriculture in mountain and rural areas is marginalized (Bournaris and Manos 2012; Flury et al. 2013; Verwoerd 2019), and a top-heavy Italian bureaucracy (Cottarelli 2018; Fontana 2021; Herzfeld 2021). Changes to this context would favor mountain agriculture and reduce the pressures on mountain farms.

Modifying the content and implementation of policies, programs, and regulations so that they are specific to the local contexts of mountain farming is one way to address their impact on farmer well-being. Policies and regulations that do not make sense either for the realities of mountain farming or because they do not integrate into existing knowledge systems risk not being followed and risk fostering distrust in government institutions. They could also create an us (the farmers) versus them (the state) mentality.

There should be greater recognition of the social and environmental value of farming. Local leaders and the media should seek to re-valorize rural lifeways. Targeted subsidies for mountain farms could further recognize the contribution of mountain farming to society. Reducing the amount of paperwork and the fees that must be paid to complete that paperwork could increase farmer well-being by reducing frustration and freeing up farmer time for farming. There should be greater oversight or a re-evaluation of policies surrounding the rental of communal malghe. Local farmers who can guarantee that they will pasture their animals at the malga in the summer should be given priority over non-local renters.

Farmer knowledge needs to be considered and valued. While the EU did seek input in its recent revision of the CAP, the degree to which the input provided by smallholder farmers was incorporated into the policies should be further scrutinized to determine whether the modifications affected farmer well-being. As Italy, like other EU countries, decides how to implement the EU CAP based on the specific needs and context of the country’s agricultural system, and given how complex and highly diverse this system is in Italy, further smallholder farmer participation in the process of designing policies, regulations, and programs could result in a more contextually specific and relevant policy and regulatory system that is less of a burden for farmers.

Many of the farmers interviewed, as with smallholder farmers across Europe, participate in alternative food networks, such as solidarity networks and local purchase groups. These farmers are taking steps to wrest power back from the industrial agrifood system at the local scale and drive the transition towards more sustainable agriculture (Lamine et al. 2012; Marsden 2013; Rossi et al. 2019; Seyfang & Haxeltine 2012). In these systems, decision-making is a participatory process that, among other things, works to “integrate local, diffused know-how with scientific knowledge” (Piccoli et al. 2023). These networks can serve as sources of social support, provide a means for local self-governance, increase farmer sense of control over their agricultural activities, and protect farmers from the vagaries of the global agricultural system by partially disengaging them from that system (Chiffoleau et al. 2019; Piccoli et al. 2023; Uleri 2018). As such, the networks can contribute to well-being (Brennan et al. 2018; Berkman et al. 2014). Thus, in addition to respecting farmer knowledge, these networks could be a source of policies that are appropriate at the local scale and aligned with farmer belief systems, and therefore more likely to be followed. Future work should further examine how participation in alternative food networks and groups may counter the negative effects on farmer well-being of the current government regulatory context.

The current study is limited by the fact that it assesses the impact of government measures only among small-scale farmers in mountain areas of Italy. Future work should assess whether similar scenarios to those presented here occur in other countries or for industrial farmers in lowland areas. While there are shared stressors that shape the well-being of farmers across developed countries, there may be differences in the scenarios that result when government measures encounter the realities of farming. The pathways through which they affect well-being might also differ. Identifying the unique and shared elements of different scenarios and their implications for well-being could help with the design of measures that favor agriculture and farmer well-being more widely. As agriculture is an important economic activity for rural development, protects and preserves natural and cultural heritage, and contributes to more vibrant rural communities, protecting farmer well-being and ensuring farmers can continue to farm should be a priority. The solutions outlined above are a first step in this direction.

Abbreviations

- EU:

-

European Union

- CAP:

-

Common Agricultural Policy

References

Alpass, F., R. Flett, S. Humphries, C. Massey, S. Morriss, and N. Long. 2004. Stress in dairy farming and the adoption of new technology. International Journal of Stress Management 11 (3): 270.

Assolombarda. 2017. Quanto costa la burocrazia? - L’Osservatorio sulla Semplificazione di Assolombarda Confindustria Milano e Monza Brianza (Rapporto completo edizione 2017). Assolombarda.

Bazzan, G., & Migliorati, M. 2020. Expertise, politics and public opinion at the crossroads of the European Commission’s decision-making: The case of Glyphosate. International Review of Public Policy 2(2:1): 68–89.

Beniston, M., and M. Stoffel. 2014. Assessing the impacts of climatic change on mountain water resources. Science of the Total Environment 493: 1129–1137.

Berkman, L.F., I. Kawachi, and M.M. Glymour, eds. 2014. Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bernard, H. R., A. Wutich, and G.W. Ryan. 2016. Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE publications.

Bernard, H.R. 2013. Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Bieling, C., T. Plieninger, H. Pirker, and C.R. Vogl. 2014. Linkages between landscapes and human well-being: An empirical exploration with short interviews. Ecological Economics 105: 19–30.

Bin, H., F. Lamm, and R. Tipples. 2008. The impact of stressors on the psychological wellbeing of New Zealand farmers and the development of an explanatory conceptual model. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety 6 (1): 79–96.

Blasch, J., B. van der Kroon, P. van Beukering, R. Munster, S. Fabiani, P. Nino, and S. Vanino. 2022. Farmer preferences for adopting precision farming technologies: A case study from Italy. European Review of Agricultural Economics 49 (1): 33–81.

Bondy, M., and D. Cole. 2019. Farmers’ health and wellbeing in the context of changing farming practice: a qualitative study. European Journal of Public Health 29 (Supplement_4): ckz186–597.

Booth, N.J., and K. Lloyd. 2000. Stress in farmers. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 46 (1): 67–73.

Bournaris, T., and B. Manos. 2012. European Union agricultural policy scenarios’ impacts on social sustainability of agricultural holdings. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 19 (5): 426–432.

du Bray, M.V., B. Quimby, J.C. Bausch, A. Wutich, W.M. Eaton, K.J. Brasier, ... and C. Williams. 2022. Red, White, and Blue: Environmental Distress among Water Stakeholders in a US Farming Community. Weather, Climate, and Society 14 (2): 587–597.

Brennan, M., T. Hennessy, D. Meredith, and E. Dillon. 2023. Weather, workload and money: determining and evaluating sources of stress for farmers in Ireland. Journal of agromedicine 27 (2): 132–142.

Brew, B., K. Inder, J. Allen, M. Thomas, and B. Kelly. 2016. The health and wellbeing of Australian farmers: A longitudinal cohort study. BMC Public Health 16 (1): 1–11.

Burchfield, E.K., B.L. Schumacher, K. Spangler, and A. Rissing. 2022. The state of US farm operator livelihoods. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 5: 795901.

Camfield, L., G. Crivello, and M. Woodhead. 2009. Wellbeing research in developing countries: Reviewing the role of qualitative methods. Social Indicators Research 90 (1): 5–31.

Chiffoleau, Y., S. Millet-Amrani, A. Rossi, M.G. Rivera-Ferre, and P.L. Merino. 2019. The participatory construction of new economic models in short food supply chains. Journal of Rural Studies 68: 182–190.

Cottarelli, C. 2018. I sette peccati capitali dell’economia italiana. Feltrinelli.

Cunsolo Willox, A., S.L. Harper, J.D. Ford, K. Landman, K. Houle, and V.L. Edge. 2012. “From this place and of this place:” Climate change, sense of place, and health in Nunatsiavut, Canada. Social Science & Medicine 75 (3): 538–547.

Daghagh Yazd, S., S.A. Wheeler, and A. Zuo. 2019. Key risk factors affecting farmers’ mental health: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (23): 4849.

Dax, T., K. Schroll, I. Machold, M. Derszniak-Noirjean, B. Schuh, and M. Gaupp-Berghausen. 2021. Land abandonment in mountain areas of the EU: An inevitable side effect of farming modernization and neglected threat to sustainable land use. Land 10 (6): 591.

De Groot, R.S., R. Alkemade, L. Braat, L. Hein, and L. Willemen. 2010. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecological Complexity 7 (3): 260–272.

Del Monte, A., and E. Papagni. 2001. Public expenditure, corruption, and economic growth: The case of Italy. European Journal of Political Economy 17 (1): 1–16.

Demossier, M. 2011a. Anthropologists and the challenges of modernity: Global concerns, local responses in EU agriculture. Anthropological Journal of European Cultures 20 (1): 111–131.

Demossier, M. 2011b. Beyond terroir: Territorial construction, hegemonic discourses, and French wine culture. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 17 (4): 685–705.

Diener, E., and E.M. Suh, eds. 2003. Culture and subjective well-being. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: MIT Press.

Dourian, T. 2021. New farmers in the south of Italy: Capturing the complexity of contemporary strategies and networks. Journal of Rural Studies 84: 63–75.

Dressler, W.W., and J.R. Bindon. 2000. The health consequences of cultural consonance: Cultural dimensions of lifestyle, social support, and arterial blood pressure in an African American community. American Anthropologist 102 (2): 244–260.

Egarter Vigl, L., E. Tasser, U. Schirpke, and U. Tappeiner. 2017. Using land use/land cover trajectories to uncover ecosystem service patterns across the Alps. Regional Environmental Change 17 (8): 2237–2250.