Abstract

Agricultural diversification in the Midwestern Corn Belt has the potential to improve socioeconomic and environmental outcomes by buffering farmers from environmental and economic shocks and improving soil, water, and air quality. However, complex barriers related to agricultural markets, individual behavior, social norms, and government policy constrain diversification in this region. This study examines farmer perspectives regarding the challenges and opportunities for both corn and soybean production and agricultural diversification strategies. We analyze data from 20 focus groups with 100 participants conducted in Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa through a combined inductive and deductive approach, drawing upon interpretive grounded theory. Our results suggest that when identifying challenges and opportunities, participants center economics and market considerations, particularly income, productivity, and market access. These themes are emphasized both as benefits of the current corn-soybean system, as well as challenges for diversification. Additionally, logistical, resource and behavioral hurdles– including the comparative difficulty and time required to diversify, and constraints in accessing land, labor, and technical support– are emphasized by participants as key barriers to diversification. Agricultural policies shape these challenges, enhancing the comparative advantage and decreasing the risk of producing corn and soybeans as compared to diversified products. Meanwhile, alternative marketing arrangements, farmer networks, family relationships, and improved soil health are highlighted as important opportunities for diversification. We contextualize our findings within the theories of reasoned action and diffusion of innovation, and explore their implications for farmer engagement, markets, and agricultural policy, and the development of additional resources for business and technical support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Agricultural diversification can bring tremendous benefits to farmers, communities, and food systems. Diversification can lessen agriculture’s negative environmental impacts and enhance farmers’ resilience to shocks, including price volatility and extreme weather (Barbieri and Mahoney 2009; Lin 2011; Gaudin et al. 2015; Tamburini et al. 2020; Baldwin-Kordick et al. 2022). Diversification’s potential is particularly salient in the United States Corn Belt, where industrialized corn and soybean production have dominated agriculture since the 1940s (Anderson 2009). While corn and soybeans have benefited a subset of agricultural stakeholders (e.g., large-scale, often multi-generational farmers, multinational agribusinesses; see National Research Council 2010; “Farming and Farm Income” 2023), corn and soybean production also present significant challenges. These include environmental problems related to soil health, water quality, and greenhouse gas emissions, as well as difficulties for new, beginning, and underserved farmers who may struggle to access sufficient land, equipment, and financial capital (Lu et al. 2018; McLellan et al. 2015; Burchfield et al. 2022; Kim et al. 2021; Nickerson and Hand 2009; Prokopy et al. 2020). While diversifying the Corn Belt has the potential to foster enhanced socioeconomic and environmental sustainability, little is known about farmers’ perceptions of diversification (Weisberger et al. 2021).

In this study, we explore farmers’ perspectives regarding challenges and opportunities of the current corn and soybean-dominated system and diversified agriculture. We draw upon interpretive grounded theory to analyze 20 focus groups in Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa conducted from 2022 to 2023.

Specifically, we ask:

-

What are the most important benefits and challenges related to corn and soybean production, as well as the diversification of cropping systems, livestock production, and market arrangements?

-

How do these benefits and challenges impact the perceived feasibility of farm-level diversification, as well as the broader diversification decision-making process?

Ultimately, farmers’ perspectives and motivations– along with external economic and sociopolitical factors, and practice characteristics– impact agricultural decision-making, including whether to diversify (Rogers 1995; Fishbein and Ajzen 2010; Reimer et al. 2012). Therefore, robust explorations of farmers’ views about diversification are necessary to improve agricultural policy, education, and research, as well as Extension and market development.

Background

What is diversification?

The term ‘agricultural diversification’ has different meanings for different audiences. Diversification can refer to agrobiodiversity, for example via increased species richness at the field or farm-level through crop rotations, intercropping, agroforestry, or integrating livestock production into farming systems (Goslee 2020; Jones et al. 2021; Blesh et al. 2023). Others emphasize the importance of synergy and ecosystem service provision in diversified systems (Martin et al. 2016). Blesh et al. (2023) define diversified farming systems as “intentional management to increase the diversity of agricultural plants and animals and non-agricultural biodiversity from field to landscape scales” (p.480). Agricultural diversification can also incorporate market, enterprise, and income diversification. The United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) list of resources for small farm diversification incorporates value-added products, on-farm processing, and services like custom work, recreation, and education (USDA National Agricultural Library 2023).

For this study in particular, the research team defines agricultural diversification in the Corn Belt considering relevance for the region and the potential to advance social, economic, and environmental benefits. At the farm-level for crop and livestock systems, diversification involves expanding rotations beyond corn and soybeans, including small grains, forages, perennial and bioenergy crops, vegetable/horticulture crops, grazed livestock, agroforestry (e.g. windbreaks, riparian buffers), and more. We explore specific benefits, challenges, and opportunities for these diversification strategies in Sect. 5.1, and employ this framework to classify farmers by diversification level (see Methods). At the market level, diversification includes production and marketing arrangements enabling farmers to move beyond traditional commodity markets for corn and soybean (e.g. direct marketing, U-pick, farmer’s markets, etc.).

However, we deliberately did not limit the discussion to this definition of agricultural diversity during focus groups, in order to gather unbiased insights from participants who represent a range of farming practices. This approach enabled an open exchange of ideas and prioritization of farmers’ views regarding diversification, which at times incorporated production methods and products not included in our definition of diversification (e.g., cover crops, conservation practices such as no-till, and specialty corn and soybean varieties).

Why diversification?

Agricultural diversification at farm, market, and landscape scales has the potential to significantly improve the well-being of humans and ecosystems in the Corn Belt. Low levels of biological diversity on farmland are a direct cause of environmental decline in the region; even small areas of diversified land use, like perennials, have been shown to significantly improve environmental quality, while landscape-scale diversification has the potential to bring greater benefits (Liebman and Schulte-Moore 2015). Other farm-level diversification strategies like small grains and grazed livestock help reduce input use, increase yield, and improve soil quality (Liebman et al. 2008; Maughan et al. 2009). The production of multiple farm products and varied income streams can help buffer farmers from economic and ecological shocks (Anosike and Coughenour 1990; Carlisle 2014), while diversified marketing approaches like direct-to-consumer marketing have been shown to increase economic resilience (Durant et al. 2023). In general, a greater diversity of crops and livestock enhances biodiversity of non-cultivated plants and animals, improves soil health and water quality, and reduces pressure from weeds, pests, and disease without compromising crop yields (Dainese et al. 2019; Tamburini et al. 2020; Beillouin et al. 2021).

Diversification faces numerous challenges, though. At the farm-level, farmers must consider their resources, economic returns, and risks, the marketing channels available to them, as well as systemic sociopolitical factors when making agricultural management decisions, many of which tend to disadvantage diversification. For this reason, crop and livestock diversification are the exception rather than the norm.

Barriers and opportunities for diversification

Extensive literature exists on the adoption of agricultural conservation practices across the U.S. and globe (Prokopy et al. 2019; Ranjan et al. 2019). This includes a variety of theoretical models and their application, including the reasoned action approach and diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers 1995; Fishbein and Ajzen 2010). The former emphasizes the importance of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in influencing behavior, while the latter places a high importance on the characteristics of innovations (relative advantage, complexity, observability, trialability, compatibility); characteristics of the adopters themselves; and dissemination of innovations through social systems (Ibid).

Despite this rich literature, there has been less focus on understanding farmers’ decisions to transition to diversified agricultural systems in the Corn Belt. Factors previously found to be associated with willingness to diversify or adoption of diversification include pro-environmental values; compatibility with current farm operations; engagement with farmer networks; land ownership; access to capital; and biophysical factors like marginal or sloping land (Anosike and Coughenour 1990; Arbuckle et al. 2009; Atwell et al. 2009; Mattia et al. 2018; Valliant et al. 2021; Asprooth et al. 2023a).

Studies have also identified significant barriers to diversification in the Corn Belt. Profitability and market access are key concerns for farmers, impacting perceived feasibility and adoption of diversified crops and livestock (Roesch-Mcnally et al. 2018; Stanek et al. 2019; Torres et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2021; Weisberger et al. 2021). Diversified agriculture is often more labor-intensive, and technology, research, and development are underdeveloped compared to corn and soybean production (Lin 2011; Bowman and Zilberman 2013; Mortensen and Smith 2020). Even if farmers perceive wildlife habitat and soil health benefits from diversification, they may be constrained by lack of infrastructure (e.g., post-harvest processing facilities), or struggles related to on-farm labor and workload (Stanek et al. 2019; Spangler et al. 2022). These challenges are situated within the context of increasing land costs and decreasing labor availability. Land prices continue to soar, with one source estimating a 12% increase in 2022 across most of the Corn Belt (The Land Report 2023).

Policy frameworks are also a major deterrent to diversifying in the region. In 2022, between 75 and 80% of agricultural land was dedicated to corn and soybean production in Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa, the majority of which went to livestock feed, ethanol, and food additives (USDA ERS 2023a; USDA ERS 2023b). The Renewable Fuel Standard artificially increases the price of corn, boosting its appeal (Condon et al. 2015; Roesch-Mcnally et al. 2018). Additionally, subsidized crop insurance– which was allocated approximately $38 billion dollars in the 2018 Farm Bill– greatly reduces risks of producing corn and soybeans relative to other crops (Bowman and Zilberman 2013; Annan and Schlenker 2015; Gottron 2019). Finally, government price supports reward adherence to corn and soybean production. For example, payments derived from the base acres of prior commodity production compensate farmers for maintaining production of only a handful of core commodity crops (Spangler et al. 2020). Together, these challenges contribute to a ‘lock-in effect’, in which socio-political, economic, research, and technological systems create path dependencies that box farmers into specialized systems (Cowan and Gunby 1996; Kallis and Norgaard 2010; Geels 2019).

Methods

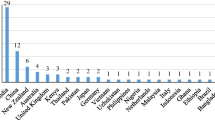

We conducted 20 farmer focus groups with 100 participants in Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa from April 2022 to February 2023. We concentrated on these states as the key producers of corn and soybeans in the region. Ten discussions were conducted in Indiana, five in Iowa, and five in Illinois. We used purposive sampling to recruit participants practicing different levels of agricultural diversification in varied geographic areas. We collaborated with local and regional agricultural organizations, including Extension offices, Soil and Water Conservation Districts, commodity groups, and local Farm Bureaus to identify and contact participants. We also identified participants at conferences, through personal networks of the research team, and via email recruitment via partner organizations’ list servs.

We utilized focus groups to ask relatively broad questions, allow for group discussion and interaction, and enable participants to build upon, affirm, or state contrasting views (Gibbs 1997; Morgan 1997) related to attitudes about diversification and the dominant agricultural system. We have found in past projects that focus groups work better than individual interviews for the types of broad questions we were asking; the interaction and idea-exchange is critical for prompting deeper thought into relatively new topics. This study represents the initial stages of a five-year project– focus groups provided an exploratory lens, captured farmers’ ideas and ways of thinking about diversification, advanced knowledge co-production, and informed subsequent research activities (see Kreuger 1988). We also offered focus group participants the opportunity to stay involved in the project.

We conducted three waves of data collection: two pilot focus groups in April 2022 which informed refinement of discussion questions, ten focus groups in August and September 2022, and eight focus groups between January and February 2023. After the second wave of data collection, we compiled overview statistics of participant demographics and production systems to inform sampling for the third wave. We then focused on recruiting corn and soybean farmers as well as additional participants in Iowa and Illinois, since these populations were less represented.

Eighteen focus groups were conducted in-person, one was conducted online via Zoom, and one via telephone. In-person focus groups were conducted in Extension offices and other public spaces (e.g., county fairgrounds). Discussions lasted between one to two hours. There were five participants on average per focus group; we tried to arrange discussions with eight or fewer participants to give everyone the opportunity to speak. Only one focus group had more than this (11 participants). Facilitators provided background information about the project and intended uses of results. We asked three main questions to gain insight into our research questions: (1) What is working well in the current agricultural system in the Corn Belt? (2) What is not working well in the current agricultural system in the Corn Belt? And (3) What do you see as the benefits and downsides of agricultural diversification? If participants asked the research team for examples of diversification, we provided examples consistent with Sect. 2.1 above, but emphasized that we wanted to hear about whatever types of diversification participants considered to be most relevant based on their own experience. Participants also completed questionnaires with information regarding age, gender, acres rented/owned, and crops/livestock produced. All focus groups were recorded and transcribed by TranscribeMe; we performed transcription quality checks on 16 of the 20 transcripts to verify accuracy.

Our intent was to have separate diversified and less diversified focus groups to create a comfortable setting for participants to share their perspectives. In some instances, focus groups had a mix of diversified and less diversified participants due to challenges with farmer availability. We observed that these mixed groups occasionally influenced participant interactions, for example when farmers more experienced with diversification offered advice or farmers with strong opinions dominated the discussion. Facilitators addressed these situations by steering the conversation and asking other participants to share. Overall, we had five discussions with predominantly less diversified participants, six discussions with predominantly more diversified participants, and nine discussions with a mix between less diversified and diversified participants.

Our analytical methods incorporate elements of ‘interpretive grounded theory’ (Corbin and Strauss 1990; Sebastian 2019). There were four main stages of data analysis: (1) initial coding, (2) intercoder reliability tests, (3) final coding, and (4) synthesis and further analysis of coded data. Open and axial coding as defined by grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss 1990) took place through an iterative process in steps 1–3, while step 4 incorporated axial and selective coding (Miller and Salkind 2002; Tie et al. 2019). Sebastian 2019 argues that in contrast to classical and constructive grounded theory approaches, interpretive grounded theory allows for prior knowledge and a literature review to strengthen research, data collection, and analysis, and the use of broad initial research questions. We adopted this approach due to its focus on inductive and abductive reasoning, and implemented data collection and analysis as interrelated processes, as described below (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Corbin and Strauss 1990; Strauss and Corbin 1990; Bruscaglioni 2016; Sebastian 2019).

First, we conducted a process of initial coding. During the second wave of data collection, the first author distilled key themes from each focus group, and used these insights– along with the focus group guide and a literature review– to develop a preliminary codebook. This codebook informed the intercoder reliability analysis as well as probing questions asked during the third wave of data collection, and contains first, second, and third-level codes (Table A1 in the Supplementary Material). Next, we conducted a process of coding among three authors to establish intercoder reliability, which helps ensure consistency among different coders and enhance trustworthiness of findings (Lincoln et al. 1985; Church et al. 2019). Analyses were conducted in Nvivo 12 (NVivo 2018). We used the Cohen’s kappa coefficient to measure intercoder reliability, which ranges from 0 (agreement no greater than that which would arise by chance), and 1 (perfect agreement), where 0.7 is considered to be a sufficient threshold to demonstrate reliability (Cohen 1960). After reaching acceptable kappa scores (0.72 for first level codes, 0.71 for second level codes, and 0.68 for third level codes), two study authors independently coded the remaining transcripts. As focus groups proceeded, we identified 18 additional codes, and conducted a final round of intercoder reliability analysis focusing only on those new codes. After achieving a suitable Cohen’s kappa (0.82 for the first transcript, 0.9 for the second transcript), the first author completed the remaining coding independently.

Finally, we synthesized and further analyzed the coded data. Synthesis methods included (1) reviewing theoretical memos and code notes, (2) using NVivo queries to further analyze code frequency for each discussion, and (3) identification of ‘core’ codes and exploration of relationships between codes through cluster diagramming, using the Jaccard coefficient to determine the coding overlap of chunks of text (Figure A1).

In the Results section below, we characterize farmers as diversified or less diversified to contextualize their responses and illuminate trends in perceptions among these groups. We based this characterization on farmer-reported data on the types of crops and livestock produced, and production practices. ‘Diversified’ farmers were classified as such if they produced three or more crops on their farm (not including alfalfa/hay or cover crops), or produced 1–2 crops plus grazed livestock, or produced grazed livestock only. All other farmers (e.g., those producing corn/soybean only or confined livestock) were classified as ‘less diversified’.

Results

The following sections overview the characteristics of participants, the perceived benefits and challenges of the corn-soybean system, and the perceived barriers and opportunities for diversified systems. The benefits and challenges of corn-soybean and diversified production are often interlinked. Throughout the Results, we include quotes that exemplify the themes most emphasized by participants. We selected quotes that best illustrated these themes, whether they arose from diversified or less diversified farmers. Some diversified farmers also produced corn and soybeans, and in some cases diversified farmers are featured in quotes discussing personal experiences with corn and soybean production.

Participant overview

Participants ranged from 23 to 89 years old. 52% of participants were in Indiana, 25% in Iowa, and 23% in Illinois; 14% of participants identified as women (Table 1). We engaged with participants with varied farm sizes - the average acres operated was approximately 506 in Iowa, 1,070 in Illinois, and 1,313 in Indiana (Table 2). Ninety-six participants were currently farming. While we did not recruit non-farmer participants, four participants were not farmers, and participated in focus groups due either to their attendance at associated recruitment events (e.g., conferences) or inclusion in recruitment by our partner organizations. This included one crop insurance adjuster, one nonoperating landowner, one crop consultant, and one agricultural input salesperson.

The top five types of crops and livestock raised by participants are displayed in Table 3 (Table A2 in the Supplementary Material outlines all crops and livestock raised by participants). The level of diversification varied from exclusive corn and soybean production to somewhat diversified production experimenting with extended rotations or grazed livestock, to highly diversified operations producing a combination of row crops, small grains, fruits and vegetables, trees, and/or other perennials.

The corn-soybean system

What’s working in the corn-soybean system?

Economics and markets

Themes related to economics and markets– for example, market access, income and productivity, and scale– were frequently highlighted as important benefits of corn and soybean production (Table A3).Many farmers emphasized that this system reduces economic risk by generating reliable, predictable income. As one farmer said:

“ […] Financially, the farmers are doing just fine in the current system. So that’s kind of a weird selling point to try and say, ‘Well, you’ll be more financially healthy if you diversify’,’ but then they’ve got an $80,000 pickup truck, [laughter] so the money is not [a good motivator].”– Less diversified farmer.

Others highlighted that the perceived economic benefits of corn and soybean production vastly outperformed diversified agriculture– even when planting on marginal land. In addition to productivity, easy access to markets was a substantial benefit for corn and soybean production. One farmer explained:

“It’s super-efficient… If I’m growing corn or soybeans, you can just open up the book and there’s 20 million different elevators within 100 miles. But if you’re growing cereal rye, well, you open up the book and there’s one name on the paper. ” - Diversified farmer.

Technology for large-scale specialized commodity production further enhanced perceived efficiency on farms, for example by decreasing labor requirements, evidenced by a farmer who told us:

“… the only reason that big operations… can exist is because we have the big equipment… if you’re not harvesting with a 12-row combine, pulling a 24-row planter, and have a fleet of four-wheel drive and green tractors, well, you’re just nobody…” - Diversified farmer.

Several participants mentioned that these market, income, and efficiency benefits generate satisfaction with the status quo among corn and soybean farmers. As one farmer described:

“The standard corn-soybean farmer, you’re putting in 5 months out of 12 and you’re pretty much assured at least break-even. And it’s a great life. Nobody tells you when to get up or go to bed or what you have to do today.” - Diversified farmer.

Indeed, several corn and soybean farmers stated that being able to take time off from farming was an important perk; one described the region’s crop rotation as “corn, beans, and Florida.” Some participants acknowledged, though, that well-being had increased for the few, rather than the many:

“It’s good money.…you had 30 to 40% of the population… 70 years ago now were farmers. Now you have 1%. Well, there’s just as much wealth there and it’s been concentrated into 1% of those -- down by 30 times. So… those of us who are left are well-to-do… I mean, it’s all about the economics.” - Diversified farmer.

This quote exemplifies the major focus that many participants placed on economic and market factors in describing their experiences, and the importance of economic outcomes of different agricultural production systems in shaping attitudes and decision-making (elaborated upon further in Sect. 5.2). In addition to these economic themes, agricultural policies were a frequent area of emphasis for participants, discussed in the next section.

Policies

Discussions of farm policies were a prominent feature of the focus groups. Participants emphasized that subsidized crop insurance and price supports created powerful incentives to produce corn and soybean, influencing the economic returns of different agricultural production decisions. Two farmers summarized this well:

“The thing that’s nice about the conventional [model] is I can be pricing my crops to sell… in a completely liquid market… I get direct payments from the government…. Crop insurance [is also] a huge component.… I can price a profit or not at the beginning of the season with corn and putting together futures, contracting, insurance, my APH [Actual Production History]… It’s easy and it’s easy to execute too.” - Diversified farmer.

“The corn-soybean establishment is, in a word, easy, but it’s also politically manufactured. We wouldn’t have ethanol if it wasn’t for the [government support]…” - Diversified farmer.

As these quotes illustrate, even diversified farmers acknowledged the benefits that agricultural policies conferred on corn and soybean production in terms of economic stability, predictability, and ease. Overall, participants acknowledged that these policies negatively influenced their ability to diverge from corn and soy production.

Technical support and access to information

Technical support for corn and soybean production from agronomists, crop advisors, and retailers from the agricultural input industry was easily accessible, according to the farmers we spoke to. Support from private advisors facilitated access to inputs and information to inform management decisions. However, some farmers somewhat sardonically noted that the system works particularly well for agribusinesses, and much of farmer decision-making is influenced by these external actors. Two farmers described this dynamic as:

“Inputs sales works really well. Our entire commodity system is based on [it].…The seed salesman is also now the chem rep who’s also the agronomist. And so the farmer goes to the one guy who tells him what seed to grow, how to plant it, where to put it, and then what inputs he needs… And by the way, that guy sells all those inputs and will contract this flyboy to come in and fly on this fungicide… And oh, he actually owns the ground rig so he can also take care of that. And so, you get… this complete system that the farmer no longer makes the decision.” - Diversified farmer.

“…I think maybe one thing that we’ve done well… [corn and soybeans is] kind of a plug-and-play system. You don’t have to be inventive or creative… You can just go and hey, buy corn, and I know what to spray it with and I know what my seed salesman tells me.…And I don’t want to suggest that conventional farmers have it easy. They work hard too, but it is a pretty easy business model to adopt…” - Diversified farmer.

The perceived ease of corn and soybean production as compared to diversified alternatives was described by participants as holding significant sway over production system decision-making. This is further discussed in Sect. 4.3.1 and 5.2 below, as the greater perceived complexity of diversified agriculture often constrained adoption, particularly among farmers with low perceived or actual behavioral control.

What’s not working in the corn-soybean system?

Land and labor

Land access and labor availability posed significant challenges and were discussed in most focus groups (Table A4). Many participants mentioned that it was more difficult than ever to find reliable workers with sufficient training, particularly as the older generation of farmers retired. As one example:

“Labor is huge right now…and I think there’s plenty of willing younger generation out there that maybe don’t have the opportunity because let’s be honest, farming is very much so family-oriented. All our dads, our fathers-in-law, grandpas are getting older, and we need to kind of shift gears, and there’s not an abundance of operators… - Diversified farmer.

Regarding land access, several farmers mentioned that their decision-making was severely constrained by high land costs since they had to keep profits and productivity up and could not afford the risk of experimentation with diversified practices, particularly on rented acres. Additionally, some participants mentioned that the land market put them in the position of deciding whether to expand their business while potentially causing conflict with neighbors. One farmer explained:

“Yes, we just farm what we own. I don’t rent land. I’ve got a lot of neighbors that do. And my wife [had] talked about, ‘Do you want to rent land, get bigger?’ and I said, ‘Okay, first off, then we’re going to have to upsize our machinery. Second, you’re going to steal land away from one of our neighbors that we have lunch with every other day…’” - Less diversified farmer.

New and beginning farmers also faced significant challenges vis-à-vis access to land. As one farmer outlined:

“This will be my first year of… managing the farm… And basically, I’m just paying cash rent to my dad…So, first year, I have no prior farm income. I had to come up with $50,000 for inputs on Monday.… I have no collateral. I have no cash… And that’s making it pretty tough with the lender to be like, ‘Yeah, we’ll just hand you some money and go farm.’ No technical farming history to show that I know what I’m doing other than I grew up on a farm and I’ve worked on a farm.… They say there’s all these aids and programs for beginning farmers, but I haven’t found one that will actually give me it, so…” - Less diversified farmer.

As all the above quotes illustrate, access to land and labor was described as directly influencing participants’ behavioral control and ability to take risks when making agricultural production decisions.

Trade-offs– productivity, policy, and technical support

Many participants, including corn and soybean farmers, emphasized the trade-offs within the current corn and soybean system, suggesting that many benefits could also be framed as challenges. For example, for many farmers the focus on efficiency and productivity had eclipsed other goals, generating negative outcomes. As one farmer pointed out:

“A lot of farmers get focused on the target of bushels per acre versus their net dollars per acre. So many of them are consumed with trying to hit 300-bushel corn or 100-bushel beans. It doesn’t matter how many inputs they have to do or use to get that.”- Less diversified farmer.

Many participants argued that the ease of modern, industrial corn and soybean production was like pushing the “easy button”, preventing farmers from considering alternatives:

“Money is the first thing. The second thing with a lot of guys is, let me hit the easy button. Because I don’t know how many guys I’ve talked to…– ‘I gave up the cultivator 20 years ago, 30 years ago. I’m not getting it back out again…’ They want easy solutions.” - Diversified farmer.

Even farmers who benefited from policies like crop insurance and the ethanol mandate within the Renewable Fuel Standard recognized their trade-offs and limitations. As one farmer who grew both corn and soybeans as well as diversified products put it:

“The crop subsidies… [increase] the revenue generated per acre. And of the revenue, then roughly 35% goes back to the landlord, and that… improves the revenue stream of that land base. Therefore, that land base now has a guaranteed revenue stream that adds an extra $100 an acre to that farm per year.”- Diversified farmer.

Some farmers also alluded to the difficulties of relying on guidance and information from retailers while trying to do the right thing for the environment and their communities. One farmer shared his worries on this topic:

“Yeah, I mean, I’m confident in what I’m doing, but… we raise GMO corn and soybeans… with products that we have been told…are safe and then… there’s a huge lawsuit against Roundup now, so it’s like, ‘Well, is there a problem with Roundup?’…And so, I’m not the one that’s done the legwork.…I’m just doing what my business is… the agronomy, that’s where I lean on [an agricultural retailer’s] shoulder… I trust what he tells us…. I want to make a good product for everybody to consume… But there’s days where I have to question, are we even doing the right thing?” - Less diversified farmer.

These quotes illustrate that while many farmers acknowledged the short-term economic advantages of corn and soybean production, many continued to question the system, highlighting drawbacks, and wondered whether other alternatives could bring better outcomes, either for farmers or for local communities.

Internal factors: attitudes, motivation, and decision-making

While participants tended to place a high importance on systemic agricultural problems (e.g., related to policy and markets), there was an acknowledgment that internal factors like attitudes, perspectives, and motivations could also pose challenges in the current agricultural system. One farmer who also worked as a farm manager of both diversified and less diversified operations pointed out that there was a general aversion to change among many farmers who may not want to depart from their established routines:

“I think one of the bigger struggles is when I interact with farmers in my more conventional system. It just seems like pulling teeth…But more just like, ‘Think outside the box.’ You don’t have to do it just because dad did it and grandpa did it.” - Diversified farmer.

Some participants argued that this aversion to change was compounded by social norms which reward producing corn and soybean the way “we’ve always done it”, rather than by exploring new practices or new crops. As one diversified farmer said: “Yeah. It’s the mentality that if you don’t [farm] corn, soybeans, your fields aren’t clean, you don’t have John Deere, you’re not successful. That’s bullshit.” Another participant suggested that if corn and soybean farmers initially perceived few benefits to changes in management practices, they were more likely to abandon them if difficulties arose:

“…that same older generation has farmed the same way for so long, just roll the soil over, plant it… And now they’re hearing about the cover crop stuff. Some guys are accepting to it, some guys aren’t. Some guys are really wanting to not like it from the start… They may have a bad experience and they’re like, ‘Yeah, I knew that cover crop thing was whack.’… you have to be dedicated to it to kind of hang with it.”– Crop consultant.

Some corn and soybean farmers expressed concern that they lacked the knowledge or skills necessary to grow different crops. For one farmer, this worry combined with difficulties related to equipment and labor to vastly reduce diversification’s feasibility:

“I did work for a guy that grew seed corn and seed beans and he had a good niche market, but he had very specialized machinery, he had very specialized facilities, and that’s profitable but… he had a lot of help, had a lot on his table, and I just don’t have the skill set for that.… I told my wife, I said, “I’m sticking to what I know.”…I’m worried…if I venture out here, am I going to lose money?”– Less diversified farmer.

Several farmers expressed that they had no interest in acquiring the marketing skills necessary to get involved in direct marketing or other types of market diversification which were perceived as necessary to make crop and livestock diversification profitable. As one farmer put it:

“I think that’s the whole problem is that I want to be in production agriculture. I don’t want to be in marketing and sales. So yeah, I would love to diversify into other crops, but I don’t want to go find that market or create that market. I don’t want to be on Twitter or Facebook…I mean, corn and soybeans are very easy.”–Less diversified farmer.

These quotes highlight examples wherein perceived practice characteristics (e.g., complexity, beliefs about likely practice outcomes) and perceived and actual behavioral control (e.g. self-efficacy and access to resources) increased the likelihood that farmers continued to produce corn and soybeans. Many farmers acknowledged that these factors led to suboptimal outcomes both for the environment and for society as a whole. Other barriers to diversification are outlined in Sect. 4.3.1 below.

Barriers and opportunities for agricultural diversification

Barriers to agricultural diversification

Economics

Economic factors were the most important barrier to diversification from participants’ perspectives– specifically income, prices, and productivity; access to markets; scale; and risk. Farmers explained that demand for diversified products was generally low, making it difficult for them to take a risk by trying a new crop. In some cases, a handful of producers had already saturated the market (e.g., for livestock feed in some contexts). For other products, producers were outcompeted by lower cost or higher quality products coming from outside the region (e.g., oats from more arid regions of the US and Canada, fruits and vegetables from California). A common complaint in several groups was the boom and bust cycles of new crops that had been pitched to them, including by Extension officials, as the ‘next big thing’ in the region, only to have the demand, processing, or other logistics collapse after farmers had already begun production. The example of the hemp market in 2019 was the most frequently discussed, although aronia berry and canola were also mentioned in one focus group.

The importance of market access and the potential risks of diversifying are illustrated by two quotes below:

“—…there is no market here for none of that stuff. So it will never go unless we have a guarantee… ‘You’re going to produce this, and you’re going to make so much money on it…’ You have to have markets for these things…” - Diversified farmer.

“I think if there is a market for whatever we’re talking about growing, whatever we’re going to diversify to, we’ll figure out– we’re farmers, we’ll figure out a way to make it work. Whether it’s equipment or fertilizer or chemicals or hiring someone with a weed zapper or whatever… We just want to make sure that we have a chance of profitability before we plant it.” - Less diversified farmer.

Market access challenges and low demand were also noted for alternative crops such as oats, rye, barley, wheat, milo, buckwheat, and sunflowers, as well as organic crops. One farmer pointed out regarding market access:

“So how do you get more diversified?… Where do you deliver milo? Where do you deliver oats?…there’s fewer and fewer local elevators, as there are dairy farms…. You have to incentivize that elevator to open up their portfolio and say, ‘We are accepting oats. We are accepting wheat. We’re accepting milo….’ They’re not going to do that because there’s no money involved in it.” - Diversified farmer.

Another major challenge emphasized by participants was scale and scalability. Producing multiple products often means that farmers do not gain the benefits of economies of scale captured by large-scale corn and soybean farmers. This can negatively affect the relative advantage of diversification (e.g., costs and time) when purchasing inputs, managing storage and quality, and securing buyers:

“Why did farms get bigger?… If you buy 100 bags of seed corn, your price is $200 a bag. If you buy 1,000 bags of seed corn, your price is $150 a bag… Everything in the industry favors scale.” - Diversified farmer.

Time, labor, land, and input use

Time, labor, land, and chemical inputs were some of the most frequently highlighted barriers to diversified agriculture, after economics. In particular, the time and effort required for diversification, limited labor availability, and the high cost and low availability of land were often underlined by diversified farmers as some of the most important obstacles they faced.

According to participants, diversified systems can place greater burdens on farmers’ time and create additional stress. Diversification often necessitates additional work along all stages of production. This includes the research required to implement new systems, labor and time for ongoing management, and the effort to identify markets for end products. As one participant explained regarding horticultural production:

“We do a retail sweet corn stand, so we’re selling direct to consumer… you got to become an expert on everything… And I actually pulled away from some of [that] because now as I’ve gotten older, and this is probably the biggest thing, is if you’re small, it’s all hard physical labor. It’s not done sitting in a tractor with GPS. And I don’t know anybody in America that loves to say, ‘Oh, well let’s do the job that’s harder versus the job that’s easier,’ I suppose, if you figure revenue is about the same.” - Diversified farmer.

Another farmer emphasized similar challenges for oat production:

“They’re trying to get people to grow oats.…The reason why people don’t grow oats anymore is, it’s a pain… You fight weeds, herbicide carryover -- try and get it dry on a wet year. Sure, it’s a good market and go sell them to the Quaker Oats in Cedar Rapids. They want 36-pound oats. You ever tried to get 36-pound oats? [laughter] It’s good feed. Draws a good price, but like I said, it’s a pain…” - Diversified farmer.

One farmer explained similar challenges in the context of livestock production:

“We just undiversified. We were trying to do the farmers market stuff and… had pigs and cows and chickens and broilers and ducks.…it was just too many irons in the fire… what broke it was we took a bunch of ducks in the processor, … and he brings them out, and they still got about a third of the feathers on them. And I’m like, ‘Hey, what’s with the feathers on the ducks, man?’ [laughter] and he said, ‘Well, ducks are really hard to pluck.’ ‘.’ [… So] I fought all day long to finish plucking these ducks because they were already sold… and it was raining, and it was just miserable.

And I thought … ‘Go on, man. What did I stand to earn with this batch of ducks anyways?’… I could have just had a few more steers and no extra work… And then you start looking at it that same way all the way around, and we whittled it from all that stuff down to the sheep [and pasture]… But I don’t know. I love the idea of having more stuff [animal variety]… but I feel like on my own, I would struggle to find resources to cover what needs [to be] covered.” - Diversified farmer.

The challenges of land and labor availability came up in most of the focus groups. Many farmers mentioned that they only had access to farmland because of previous family ownership. On the other hand, the potential for diversification to bring supplemental income on idle land was attractive, even for corn and soybean farmers. Several participants mentioned the importance of educating landlords about the benefits of diversified practices.

Labor availability was mentioned in the context of both corn and soybean and diversified operations. Several participants had positive experiences with the H-2 A visa program for temporary agricultural workers. However, one participant mentioned that communication challenges necessitated simplification of management decisions after increasingly relying on H-2 A laborers:

“If I step back and look at 8 to 10 years ago when I was [trying to diversify] and then I was also going through my labor issue…now I’ve gotten into my H-2A workers to where there is a language barrier there, right? So I actually had to go away from my… strip-till practice… that adds even more complication to trying to implement cover crops… Do I think it’s a great practice…? Absolutely… But there’s a whole ‘nother level of management.” –Less diversified farmer.

Some products, like horticultural food crops, organics, and livestock, were frequently mentioned in relation to challenges with labor intensity or availability. Labor constraints also were mentioned in the context of alternative marketing arrangements like food hubs:

“We ended up hiring a person to be the manager because we discovered very quickly none of us had that skill set…in the end, the whole thing folded because the one person we had running it was trying to do everything themselves…It wasn’t one thing went bad. It was the entire structure never existed in the first place, so we had to build it from the ground up. There was never any major support from USDA or anything.”- Diversified farmer.

Finally, input use and associated agrochemical overspray and drift was a particular challenge for horticulture producers. Several farmers mentioned that when they experienced crop loss due to overspray, they didn’t have much recourse, other than attempting to verbally resolve the issue with neighbors. One participant mentioned that they had signed up for a program called FieldWatch which provided signage for their property, helping to address overspray issues. Dicamba and 2,4-D used in corn and soybean production were mentioned as negatively affecting the feasibility of horticulture production due to toxicity and ease of spread.

Agricultural policies

Systemic issues related to agricultural policy were frequently situated as major challenges for diversification. Although farmers discussed a wide variety of government policies, including biofuel and price support programs, crop insurance was discussed the most. Many, if not most, of the diversified farmers we spoke with– including horticulture producers, agroforestry producers, and farmers growing small grains via companion or relay cropping - were not able to attain crop insurance for diversified crops, whether due to lack of production history information for newer crops, limited time to complete the necessary paperwork, or the fact that insurance programs were not tailored to crops with high annual changes in productivity, like young perennials. As two farmers explained:

“If you have specialty crops, [crop insurance] does not work…. The latest iteration of that came out… It was supposed to fix the problem… we would have to hire a full-time person to do the paperwork… the people who write these things have no idea how you operate a vegetable farm… in this field, there may be three crops planted in the same year. That field may be grazed… There’s no way to put this in the paperwork. The first version that came out, we ran down to the FSA to sign up, and they said, ‘What cover crop or what specialty crop do you grow?’ I said, ‘Oh, we grow 40 different vegetable crops.’ Well, there were three lines on the form.… the people who write these insurance programs need to understand how it works.” - Diversified farmer.

“The new insurance programs– I was looking into them, too, and they were basing your payouts on what your previous two to three years were. We’re in perennials. Each year, our productivity is supposed to go up 20 to 50%. And so, if you’re going back three years, that tree maybe didn’t even produce for that year…” - Diversified farmer.

Another diversified farmer told us that their insurance claim for onion production was denied due to limited insurer knowledge of the crop, requiring them to appeal to local committees to receive their payout. Many participants also emphasized that crop insurance was one piece of a larger policy jigsaw puzzle incentivizing the status quo and inflating the profits from corn and soybeans, even in cases where they would not otherwise be financially viable. As one farmer said:

“The problem with crop insurance… is it keeps everybody in the paradigm that they’re in, whether it’s working for them or not. It locks in because it’s too risky to change… In my county by crop insurance standards, you can’t physically grow small grains. You can’t physically grow popcorn. You can’t physically grow vegetables because none of these things are insurable…. But as soon as you cross the county line, it’s totally possible to grow these things, and you can get insurance…And there’s so many hurdles in getting something to be insurable, nobody bothers with it. It takes years of data to do.” - Diversified farmer.

This direct reference to the ‘lock-in’ effect illustrates this participant’s frustrations with the inertia of inflexible insurance policies favoring existing production systems, which exacerbated the difficulty of producing diversified crops.

Technical support

Access to technical support was also a commonly mentioned barrier to diversification. Several farmers mentioned that while information about diversification had become more readily available through the Internet, “how-to” guides with information about how to get started in new diversified products were lacking, and many local technical support staff were ill-equipped to give advice. Participants mentioned that it would be helpful to understand diversification options based on their available equipment, local climate and markets, as well as specific certification requirements (e.g., for livestock or organic production). One participant wished they had access to business cases with accessible information on costs and revenue to inform management decisions, but said they did not know if such resources existed.

Opportunities for agricultural diversification

Markets and income

Despite the challenges with market access mentioned previously, several participants shared success stories about profitably marketing diversified products. These were often through alternative marketing arrangements, including direct-to-consumer marketing, farmers’ markets, niche markets (e.g., goat meat), food hubs, and co-ops, as well as U-pick operations and agri-tourism. These arrangements were often for relatively small volumes of product. Among the alternative marketing arrangements discussed, direct-to-consumer meat marketing was the most frequently mentioned. Participants saw significant changes in consumer preferences during the Covid-19 pandemic, which increased market access, bolstered local food systems, and offered benefits to their communities. As two farmers outlined:

“…We’re living in a day and age of technology and market access and market awareness that… really gives us more opportunities than what we had in the past, and the ability to connect directly with the customer through social media… Covid scaring everybody away from grocery stores, find the farmer, all this stuff… There’s just been lots of positive things to drive change.”-Diversified farmer.

“…for us, the drive to be diversified even though it requires more work is more of a survivability feature, and we saw that, especially during the pandemic, when our local small-town grocery store suddenly could not get fresh produce or fresh vegetables or eggs… All of a sudden, our phone was ringing off the hook because people were like, ‘Oh, yeah… they have eggs that they sell at the farm market. I wonder if they could have produce?’… It really brought to light the fact that we need more diversified growers to be able to support their local communities in a time of crisis…” - Diversified farmer.

Several farmers mentioned price premiums and other income benefits for raising crops outside of typical corn and soybean production. This included benefits for raising seed corn, cover crop seed (including rye and vetch), and wheat (in some cases), as well as specialty varieties like high oleic or Plenish soybean, non-GMO soybean, and food grade soybean. Some farmers producing cover crop seed saw significant income benefits, particularly through relay cropping. Alfalfa/hay production was also mentioned as being lucrative by several participants. In some cases, diversified production enabled farmers to increase profits without expanding farm size. There were several examples of successful cooperative models, including for agroforestry products (chestnuts), and one horticultural producer mentioned that they had increased prices due to water challenges in California and subsequent decreased supply. These examples illustrate the importance of market diversification and development in enabling farm-level crop diversification. To further demonstrate this point, several participants discussed the need for large-scale investment in diversified markets, including in R&D, processing, and manufacturing.

Farmer networks and family relationships

Many diversified farmers remarked on the positive impact that farmer networks had on their ability to diversify. Virtually connecting with other farmers, for example via Facebook, Twitter, AgTalk, and other venues helped them acquire information about diversification, supplementing their potentially more competitive local networks. Connecting with other farmers at conferences, for example the Marbleseed organic farming conference, Grassworks grazing conference, or the No-Till conference– as well as visiting others’ operations– also brought benefits. Several farmers suggested setting up additional resources to connect diversified farmers (for example through a list or geo-database of diversified operators), to share specialized production knowledge or set up new partnerships. Access to farmer networks helped participants learn about marketing opportunities, equipment modifications, and management strategies. Other farmers mentioned that they shared labor or equipment with neighbors. As one diversified farmer said,

“And with social media and stuff, I have all the phone numbers of those guys that are on that bleeding edge… if I have a question on something, I know who I can talk to.”

Family relationships were also frequently mentioned in the context of diversification. There were several examples of operations that diversified because they had multiple children who wanted to come back to farm. As one farmer explained:

“…it’s about who’s coming back to the farm. So he has got six kids. This guy has one farm. He wants to farm a thousand acres, but you could probably do that for him. If you want to add family, a couple of thousands is not enough unless you diversify.” –Less diversified farmer.

Bringing in family members to support a new part of the business allowed participants to focus on the parts of their work they enjoyed the most, while potentially avoiding other activities (like marketing). As the same farmer said:

“…My wife does all [the sales]. If it wasn’t for her, I wouldn’t sell freezer beef…I mean, I’m just not a people person. I want to produce a product and I want to do the best I can at that. I don’t want to be that guy that does every step.” –Less diversified farmer.

These quotes outline how family relationships affected both the perceived benefits of diversification, as well as farmers’ behavioral control in agricultural decision-making.

Farm management and soil health

Farm management related to diversification was a frequently discussed topic, and many participants shared successful examples of what worked for them. Technology and equipment helped enable transitions to diversified systems in some cases -- for example, GPS-based virtual fences to facilitate grazing cattle, special seed separation equipment to separate soybeans from grains after harvest, and “weed zappers” used in organic production. High tunnel systems were mentioned as enabling diversified vegetable production. Several farmers felt that technology options to estimate their carbon footprint could help them capitalize on incentive programs and policy frameworks (e.g., 45Z Tax credits through the Inflation Reduction Act), creating a different ‘scoreboard’ for farming beyond corn and soybean yield.

Several diversified farmers mentioned that they enjoyed continuously learning by adaptively managing diversification on their operation:

“…The biggest phrase that has always bothered me, especially since I got into no-till and trying to do things that are environmentally conscious, I hear farmers all the time say, ‘That’s not how we do it,’ or ‘This is how we’ve always done it.’ So to me, diversification means constantly learning, constantly doing something different. And it may not always be just about dollars and cents.”–Diversified farmer.

Finally, the soil health benefits of diversification were often emphasized by participants, whether from growing cover crops, grazing livestock, incorporating a third crop into rotations, or growing perennials like alfalfa/hay. As one participant said:

“Well, I think another piece of that is risk management and just overall resilience. We kind of get stuck in the corn-soybean rotation, and if we get two or three weeks of bad weather at the wrong time for each crop, it gets pretty tough. But with more diversification, we spread that risk… And again, from a soil health, sustainability point of view, we may have opportunities to ensure that the next two or three generations are going to… be even more successful than what we are.” - Less diversified farmer.

The examples listed above demonstrate that many farmers perceived important benefits from diversification, whether related to their own internal motivation, curiosity, and enjoyment; the economic stability of their farm; or environmental benefits. These perceived positive outcomes helped motivate diversification.

Discussion

Diversification’s barriers and opportunities

While a transition to more diversified agriculture involves significant obstacles, our results suggest several important opportunities for different diversification strategies. We grouped our results for five specific farm-level crop and livestock diversification strategies– grazed livestock, agroforestry, horticultural food crops, small grains, and alfalfa/hay (see Sect. 2.1)– to identify commonalities and differences based on participant perceptions. Table 4 displays an overview.

These barriers and opportunities largely comport with previous literature focused on diversification. Small grains may be appealing due to their relative compatibility with current farming practices and equipment, which also enhances trialability. Despite this, a couple of farmers pointed out that harvest times for oats and wheat coincided with the summer ‘off-season’ making it less attractive due to labor considerations. Additionally, market opportunities for cover crop seed as well as farm management adaptations like relay cropping can enhance the profitability of extended rotations (see Martins et al. 2021; Tyndall et al. 2021). However, challenges remain related to quality, productivity, and germination of cover crop seed (Han and Grudens-Schuck 2022; Asprooth et al. 2023b). Farmers had varying perspectives on prices for small grains, with some mentioning challenges finding a desirable price and others highlighting opportunities. Previous research has shown that while integrating small grains in rotations can help bolster corn and soy yield and reduce excess nitrogen, profitability results are mixed (Liebman et al. 2008; Davis et al. 2012; Haan et al. 2017; Singh et al. 2021)

Our results suggest that farmers perceived important environmental benefits to grazed livestock production, for example related to soil health, which aligns with previous research in the Corn Belt (Hayden et al. 2018; Roesch-Mcnally et al. 2018). Furthermore, the emphasis farmers placed on the profitability of direct marketing for grazed livestock and horticulture food crops is borne out by previous literature. Several studies have found that direct marketing through, for example, online sales and CSAs increased resilience and economic stability for farmers during Covid-19 (Bachman et al. 2021; Durant et al. 2023). Exposure to agroforestry was generally low, and perhaps partially due to insufficient access to information, there was some skepticism from less diversified participants regarding agroforestry’s viability in the Corn Belt. This is supported by previous studies of interest in agroforestry adoption in Illinois and Iowa, which have shown that perceived environmental benefits (e.g., pollinator and wildlife habitat) can be outweighed by lack of information and concerns related to equipment, processing, and market access, as well as the time and risks associated with adoption (Atwell et al. 2009; Mattia et al. 2018; Stanek et al. 2019). There was also relatively little discussion among participants of perennial crops outside of alfalfa/hay, and diversified bioenergy and biomass crops like miscanthus and switchgrass were only mentioned a couple of times.

To diversify or not to diversify? A theorical framework

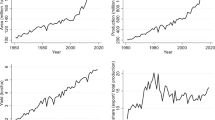

Our results help elucidate decision-making processes around diversification adoption, and many of our findings align with the framework of the reasoned action approach (Fig. 1, Fishbein and Ajzen 2010). The figure outlines how ‘background factors’ (Fig. 1, Box 1) – e.g., agricultural policies, technical support, and market access – intermingle with farmer perceptions of diversification’s barriers and benefits (Box 2) to influence motivations to diversify. Social norms related to what ‘successful farming’ looks like (Box 3) also influence the intent to adopt. Existing policies and technical support networks create a strong short-term economic relative advantage for corn and soybean production, fortified by decades of path dependence and technological development (Box 1, see Bowman and Zilberman 2013; Magrini et al. 2019; Spangler et al. 2020). Attitudes about diversification can either constrain or facilitate adoption, and may be shaped by broader environmental attitudes, as well as perceptions regarding the likely outcomes of diversification and the characteristics of diversification strategies. For example, a farmer may be interested in diversification because they expect to improve soil health, harness their creativity, involve family members in their farm, or maintain profits on a smaller amount of land. On the other hand, many corn and soybean farmers we spoke with expressed concerns about potential negative economic outcomes of diversification related to decreased profitability and lack of market access; this comports with previous research (Roesch-Mcnally et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2021; Weisberger et al. 2021).

Even if a farmer is motivated to diversify, they may be constrained by additional challenges, including time, capacity, labor availability, and other personal and operational characteristics, as outlined in Boxes 4 and 6 (Anosike and Coughenour 1990; Atwell et al. 2009; Spangler et al. 2022). In the figure, these factors are categorized under ‘perceived’ and ‘actual behavioral control,’ since they can influence farmers’ ability to act on their motivations (see Ajzen 2002). The farmer who ‘undiversified’ after their experience plucking ducks is an example of this intention-action gap.

If a farmer has sufficient motivation and resources and chooses to diversify, their experiences with adoption (Box 7) will shape future decision-making. Farmers who experience negative outcomes – whether due to insufficient technical support, challenges with markets or infrastructure, or climatic conditions – may stop diversifying. On the other hand, our results suggest that formal and informal farmer networks can help bolster diversification and enhance observability of diversified practices; this is also borne out by previous studies (Kroma 2006; Atwell et al. 2009; Asprooth et al. 2023a). Additionally, some farmers can sustain their motivation to diversify and troubleshoot successfully through challenges, adapting where needed, drawing on their farm management knowledge, available labor, and other resources. As more farmers diversify, information-sharing regarding diversification success stories increases, positively influencing farmer perceptions of diversification outcomes.

Conclusion and paths forward

Our results emphasize three main points related to the future of diversification in the Corn Belt. First, practical strategies are needed to address diversification’s economic and market challenges, which participants consistently emphasized as the most important factors limiting diversification. Second, there is also a need to address the significant logistical, resource, and behavioral hurdles related to the comparative difficulty, time intensiveness, and complexity of adopting diversification as compared to corn and soybean or confined livestock alternatives. Finally, systemic factors like agricultural policies play a significant role in shaping the two main challenges discussed above, and thus must be carefully evaluated for improvement.

On the first point, market development interventions from public and private sectors should focus on improving access to mass and niche markets and securing price premiums and subsidies for diversified farmers to enhance profitability and decrease risk. This could include (1) investments in research and development, processing, and manufacturing for diversified products; (2) support for local-level initiatives, including food hubs, co-ops, and training programs for direct marketing; and (3) price premiums, subsidies, or other incentives for sustainably produced diversified products. We expect that approaches that are supported by actors throughout the supply chain– such as mandatory local food procurement for governmental institutions– can change the current agricultural landscape and strengthen the local economy.

Additionally, several interventions may help lessen challenges related to the time and effort required to diversify, enhancing the relative advantage of diversification at farm-level and making it more feasible for interested farmers to pursue diversification. This includes (1) the creation and dissemination of business cases and how-to guides for diversification, (2) focusing engagement efforts in areas already diversifying and fostering farmer-to-farmer collaboration, and (3) training technical support practitioners in diversification strategies (Extension, NRCS, certified crop advisors, etc.). First, business cases can help farmers evaluate and select diversification options. Due to the importance of profitability in the decision-making process, business cases must provide clear information on costs and benefits of diversification, describing compatibility with available equipment. How-to guides could cover topics like selecting additional crops, ensuring high quality when growing third crops for seed or food-grade markets, or utilizing diversification to enhance profitability on marginal land. These guides could outline contact information for relevant sources of technical support, and be disseminated through trusted agricultural organizations. Second, our results underline the importance of social networks in increasing adoption; diversification is more likely to naturally spread in contexts where some farmers have already diversified. Thus, research identifying geographic hotspots and existing networks for diversification can help inform targeting of further engagement. Supporting and strengthening cooperation among farmers -- for example via equipment and knowledge sharing, and coordination of production and marketing -- is an important mechanism to enhance the feasibility of diversification. Finally, diversification expertise should be incentivized and enhanced within technical support entities.

Caution should be used when promoting the adoption of specific crops, considering participants’ negative experiences related to boom and bust crops like hemp, aronia, and canola (among others). To the extent possible, recommendations for diversified crop adoption should consider and communicate relevant context about market demand, prices, and local and regional processing capacity. Furthermore, where possible, buyers should be included in discussions about diversification to help ensure sufficient market demand.

Finally, our findings suggest a need for policy changes to increase the potential for farm, market, and landscape-level diversification. While providing exhaustive policy recommendations is beyond the scope of this paper, one high-priority option to consider is making crop insurance work better for diversified farmers. This could include providing crop insurance premium discounts for diversified production, or more comprehensively tailoring current programs to the realities of diversified systems such as by allowing for a higher number of crops or accounting for temporal variations in productivity in production histories. Overall, our results highlight the urgent need for transformation of the agricultural system to harness diversification’s benefits.

Notes

Either as a crop or a cover crop.

References

Ajzen, Icek. Perceived Behavioral Control, and Self-Efficacy. 2002. Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32: 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x.

Anderson, J. L. 2009. Industrializing the Corn Belt: Agriculture, Technology, and Environment, 1945–1972. Dekalb, IL: Northern Illinois University.

Annan, Francis, and Wolfram Schlenker. 2015. Federal Crop Insurance and the disincentive to adapt to Extreme Heat. American Economic Review 105: 262–266. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20151031.

Anosike, Nnamdi, and C. Milton Coughenour. 1990. The socioeconomic basis of Farm Enterprise diversification Decisions1. Rural Sociology 55: 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.1990.tb00670.x.

Arbuckle, J., Corinne Gordon, Andrew Valdivia, John Raedeke, Green, and J. Sanford Rikoon. 2009. Non-operator landowner interest in agroforestry practices in two Missouri watersheds. Agroforestry Systems 75: 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-008-9131-8.

Asprooth, L., M. Norton, and R. Galt. 2023a. The adoption of conservation practices in the Corn Belt: the role of one formal farmer network, practical farmers of Iowa. Agriculture and Human Values. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-023-10451-5

Asprooth, Lauren, M., A. Krome, A. Hartman, R. McFarland, Galt, and L. S. Prokopy. 2023b. Drivers and deterrents of small grain adoption in the Upper Midwest. East Troy, WI: Michael Fields Agricultural Institute.

Atwell, Ryan C., A. Lisa, and Schulte. 2009. and Lynne M. Westphal. Linking Resilience Theory and Diffusion of Innovations Theory to Understand the Potential for Perennials in the U.S. Corn Belt. Ecology and Society 14. Resilience Alliance Inc.

Bachman, Grace, Sara Lupolt, Mariya Strauss, Ryan Kennedy, and Keeve Nachman. 2021. An examination of adaptations of direct marketing channels and practices by Maryland fruit and vegetable farmers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Agriculture Food Systems and Community Development 10: 283–301. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2021.104.010.

Baldwin-Kordick, Rebecca, Mriganka De, Miriam D. Lopez, Matt Liebman, Nick Lauter, John Marino, D. Marshall, and McDaniel. 2022. Comprehensive impacts of diversified cropping on soil health and sustainability. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 46. Taylor & Francis: 331–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2021.2019167.

Barbieri, Carla, Edward Mahoney. 2009. Why is diversification an attractive farm adjustment strategy? Insights from Texas farmers and ranchers. Journal of Rural Studies 25: 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2008.06.001.

Beillouin, Damien, Tamara Ben-Ari, Eric Malézieux, Verena Seufert, and David Makowski. 2021. Positive but variable effects of crop diversification on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Global Change Biology 27: 4697–4710. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15747.

Blesh, Jennifer, Zia Mehrabi, Hannah Wittman, Rachel Bezner Kerr, Dana James, Sidney Madsen, and Olivia M. Smith et al. 2023. Against the odds: Network and institutional pathways enabling agricultural diversification. One Earth 6: 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2023.03.004.

Bowman, Maria S., and David Zilberman. 2013. Economic Factors Affecting Diversified Farming Systems. Ecology and Society 18.

Bruscaglioni, Livia. 2016. Theorizing in grounded theory and creative abduction. Quality & Quantity 50: 2009–2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0248-3.

Burchfield, Emily K., Britta L. Schumacher, Kaitlyn Spangler, and Andrea Rissing. 2022. The state of US Farm Operator livelihoods. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 5.

Carlisle, Liz. 2014. Diversity, flexibility, and the resilience effect: lessons from a social-ecological case study of diversified farming in the Northern Great Plains, USA. Ecology and Society 19. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06736-190345. The Resilience Alliance.

Church, Sarah P, Michael Dunn, and S Prokopy Linda. 2019. Benefits to Qualitative Data Quality with Multiple Coders: Two Case Studies in Multi-coder Data Analysis.

Cohen, Jacob. 1960. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement 20. SAGE Publications Inc: 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104.

Condon, Nicole, Heather Klemick, and Ann Wolverton. 2015. Impacts of ethanol policy on corn prices: a review and meta-analysis of recent evidence. Food Policy 51: 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.12.007.

Corbin, Juliet M., Anselm Strauss. 1990. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology 13: 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593.

Cowan, Robin, Philip Gunby. 1996. Sprayed to death: path dependence, lock-in and Pest Control Strategies. The Economic Journal 106: 521–542. https://doi.org/10.2307/2235561.

Dainese, Matteo, Emily A. Martin, Marcelo A. Aizen, Matthias Albrecht, Ignasi Bartomeus, Riccardo Bommarco, and Luisa G. Carvalheiro et al. 2019. A global synthesis reveals biodiversity-mediated benefits for crop production. Science Advances 5: eaax0121. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax0121.

Davis, Adam S., D. Jason, Craig A. Hill, Ann M. Chase, Johanns, and Matt Liebman. 2012. Increasing cropping system diversity balances productivity, profitability and environmental health. PloS One 7: e47149.

Durant, Jennie L., Lauren Asprooth, Ryan E. Galt, Sasha Pesci Schmulevich, Gwyneth M. Manser, and Natalia Pinzón. 2023. Farm resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: the case of California direct market farmers. Agricultural Systems 204: 103532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2022.103532.

Editors, Land Report. 2023. Farmland Values Jump 12% in Corn Belt. The Land Report.

Farming and Farm Income. 2023. USDA Economic Research Service. August 31.

Fishbein, Martin, Icek Ajzen. 2010. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned Action Approach. New York, NY, US: Psychology.

Gaudin, Amélie CM, N. Tor, Alan P. Tolhurst, Ken Ker, Cristina Janovicek, Ralph C. Tortora, Martin, and William Deen. 2015. Increasing crop diversity mitigates weather variations and improves yield stability. PloS One 10: e0113261.

Geels, Frank W. 2019. Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: a review of criticisms and elaborations of the Multi-Level Perspective. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 39. Elsevier: 187–201.

Gibbs, Anita. 1997. Social research update: Focus Groups. Department of Sociology, University of Surrey.

Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction.

Goslee, Sarah C. 2020. Drivers of Agricultural Diversity in the Contiguous United States. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 4.

Gottron, Frank. 2019. The 2018 farm Bill (P.L.115–334): Summary and Side-by-side comparison. R45525. Congressional Research Service.

Haan, Robert L., Matthew A. De, Schuiteman, and Ronald J. Vos. 2017. Residual soil nitrate content and profitability of five cropping systems in northwest Iowa. PLOS ONE 12 Public Library of Science: e0171994. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171994.

Han, Guang, Nancy Grudens-Schuck. 2022. Motivations and challenges for Adoption of Organic Grain production: a qualitative study of Iowa Organic Farmers. Foods 11: 3512. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11213512.

Hayden, Jennifer, Sarah Rocker, Hannah Phillips, Bradley Heins, Andrew Smith, and Kathleen Delate. 2018. The importance of Social Support and communities of Practice: Farmer perceptions of the challenges and opportunities of Integrated crop–livestock systems on organically managed farms in the Northern U.S. sustainability 10. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: 4606. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124606.

Jones, Sarah K., C. Andrea, D. Sánchez, Stella, Juventia, and Natalia Estrada-Carmona. 2021. A global database of diversified farming effects on biodiversity and yield. Scientific Data 8 Nature Publishing Group 212. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-01000-y.