Abstract

Background: Although interprofessional student led health clinics have been implemented worldwide, the impact of this model await confirmation. Objectives: To conduct a critical analysis of the literature on interprofessional student led clinics, and the views of stakeholders on feasibility and the barriers and facilitators to implementation. Design: A scoping review, evidence synthesis and quality appraisal were conducted using PRISMA Scr. Eight databases were searched from 2003 to 2023: Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), Cochrane, Scopus, ERIC, Web of Science and Informit Health Collection. A qualitative descriptive approach was used to analyse data from patients, students and educators and inductive thematic analysis identified emergent themes. Results: Forty-six studies were included from a yield of 3140 publications. A key theme to emerge was that patients perceived improvements in their health and wellbeing and valued gaining health information from student led clinics. Student experiences were mostly positive although some found it challenging to work in interprofessional teams and roles were not always clear. The clinics enabled students to improve communication skills and autonomy. Clinical educators reported that students benefited from experiential learning within an interprofessional context. The clinics were feasible, provided that sufficient funding, infrastructure, staff and resources were available. Barriers to implementation included lack of funding, excessive waiting times and non-aligned student timetables. Pre-clinic orientation and support from on-site clinical educators facilitated implementation. Conclusions: Despite some challenges with implementing interprofessional student led clinics, they can have a positive impact on student learning and patient experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interprofessional student led health clinics (SLC) have been implemented worldwide using different models, based on the healthcare needs of patients (Stetten et al., 2019) and available infrastructure, clinical supervision and resources (Buckley et al., 2014; Haggarty & Dalcin, 2014; Sick et al., 2014). Services are delivered by students from two or more health or social care disciplines, supervised by a registered health professional in a community-based health or social care setting (Briggs & Fronek, 2020; Lie et al., 2016). Interprofessional student led clinics have been argued to benefit students and patients (Broman et al., 2022; Schutte et al., 2015; Tokolahi et al., 2021). They often involve a combination of medical, nursing and allied health students (Horbal et al., 2019; Schmitt et al., 2013) and sometimes include non-health trainees such as interpreters (Davis, 2021), engineering students (Hayward et al., 2016) or law students (Rock et al., 2014). Students can be involved in clinics as volunteers or through university clinical placements (Forbes et al., 2021; White et al., 2018). A wide range of student led clinics have been reported, including student led, student run, student-delivered, student-assisted, student-initiated, student-facilitated, student-implemented, and student focussed service-learning clinics conducted as part of clinical education placements (Huang et al., 2021; Leung et al., 2016, 2022; Wynne & Cooper, 2021).

Interprofessional student led clinics give students the opportunity to learn with, from and about each other (Hopkins et al., 2022; World Health Organization, 2010). Students have reported increased ownership and responsibility for client care when participating in this type of clinical education (Schutte et al., 2015). There is also preliminary evidence of improved collaborative skills (Hopkins et al., 2022; Wilson et al., 2023), improved role clarity (Horbal et al., 2019), better understanding of patient-centred care (Huang et al., 2021) and an appreciation for working with disadvantaged people (Sick et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2023). Briggs and Fronek (2020) reviewed student experiences of student led clinics, finding them to facilitate teamwork, a finding shared by Timm and colleagues (2021).

Student run free clinics date back to the 1960s and began in the USA as altruistic student enterprises to serve minority groups (Simpson & Long, 2007). Some clinics enabled access to healthcare for people who could not afford private health insurance (Palma et al., 2020; Stuhlmiller & Tolchard, 2015). They included low-income individuals, homeless people, immigrants, refugees and others (McElfish et al., 2018; Ng & Hu, 2017; Sick et al., 2017). Student clinics sometimes benefit people living in rural areas (Spencer et al., 2015; Stuhlmiller & Tolchard, 2015) and older people (Fung et al., 2022; Kent et al., 2016). They can provide low cost health services (Danhausen et al., 2015; Kent & Keating, 2013) and be effective at improving the management of chronic conditions (Gustafsson et al., 2016; Suen et al., 2020). Patients have reported benefits from the health knowledge gained (Burgess & Roberts, 2022; Ng et al., 2020), improved lifestyle and self-efficacy (Stuhlmiller & Tolchard, 2018) and training of students (Isaacson et al., 2014; Meuser et al., 2022). Clinical educators noted that pre-clinical training is usually discipline specific (Hall et al., 2012; VanKuiken et al., 2016), and interprofessional clinics afford greater preparedness for multi-disciplinary practice (Lestari et al., 2016; van Diggele et al., 2020).

With the rapidly growing literature on this topic, there is a need to synthesise recent findings on patient, student and clinical educator views on student led interprofessional clinics. The aim of this review was to address this gap and to understand the feasibility and barriers and facilitators to implementation of this model of health professional education.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This scoping review was completed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018). It was based on the five stages of the methodological framework by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), later refined by Levac and colleagues (2010). Scoping reviews map, summarize and disseminate the available evidence on a topic (Munn et al., 2022). They also help to evaluate the type, range and extent of research already published (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Peters et al., 2020). The review was registered a-priori in Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5VBDZ).

Identifying relevant studies

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they: (i) described interprofessional health services delivered to patients by students of at least two healthcare disciplines. Students of one discipline had to work together with students of another discipline. (ii) reported outcomes for patients, students and clinical educators and (iii) were peer-reviewed. A clinical educator was defined as a registered professional, affiliated with an educational institution or healthcare facility who was responsible for supervising or educating students. Reasons for excluding studies were: (i) no patient outcomes reported, (ii) not in English, (iii) publication older than 20 years, (iv) intervention delivered by a clinician not a student, (v) students not enrolled in higher education, (vi) opinion piece, thesis or review, or (vii) full text not available.

Search

A search strategy was created using both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free text terms, available in Supplementary Material 1. This process was guided by a university librarian and was iterative and cross checked with key relevant literature in the topic. The key search concepts were: (i) student led health clinics and (ii) interprofessional structure of service delivery (two or more health disciplines working together). The search strategy was initially developed for Medline (Ovid) and subsequently adapted to each of the following databases: Embase (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), Cochrane, Scopus, ERIC, Web of Science and Informit Health Collection. Additional studies were hand searched in reference lists of included studies and existing systematic reviews relevant to this field of research. A simple search was also conducted in the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) to screen for relevant studies not picked up elsewhere.

Study selection

Covidence®, a web-based software to manage reviews, was used (Covidence systematic review software). In the first stage of screening, duplicates were removed, all titles and abstracts were screened by two blinded reviewers (JPV, MS), followed by full text screening against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer (MEM).

Data charting

Data from each article were extracted using the Covidence® platform, then transferred to a database in Excel. A data extraction chart was created to collect specific information on the characteristics of interprofessional student led health clinics. We extracted data for the following variables: author, year of publication, country, study design, study aims, clinic or project name, key term used to describe the service (student led /run /developed /assisted /service learning), target population, number of patients, setting, disciplines and numbers of students and supervisors, types of intervention delivered by students, amount and mode of supervision, period of data collection, duration and type of student involvement in the clinic (placement or volunteer), method of collaboration between students (teams, planning and debrief meetings, group preparation or delivery of educational content) outcome measures, results, barriers and facilitators, and major findings. Feasibility data were extracted from each article, pertaining to (i) technical resources, equipment, set up, environment (ii) cost/ benefit (iii) organisational structure, processes, staffing, skills (iv) marketing of clinic services. We also analysed the barriers and facilitators to implementation of interprofessional student led clinics.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Quantitative data were tabulated (Supplementary Material 2) and summarized to present an overview of student clinics identified in the review, including the geographical location, design, healthcare setting, disciplines, numbers of participants, target clientele and type of intervention. A qualitative descriptive approach was employed to analyse the qualitative data on three primary populations of interest: patients, students and clinical educators (Stanley, 2014). Each of the three datasets were coded separately and inductive thematic analysis was used to identify emergent themes from the bottom up (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Codes and themes were checked and verified by three reviewers (JPV, MEM, MS).

Quality appraisal

Critical appraisal of the included studies was conducted using the Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., 2018). The MMAT assesses methodological quality for categories: (i) qualitative (ii) quantitative randomised controlled trial (RCT) (iii) quantitative non-RCT (iv) quantitative descriptive (v) mixed methods. The quality appraisal was completed by two reviewers (JPV, CT) and consensus was provided by a third reviewer (MEM) where required. We included an overall quality rating by adding the number of items marked ‘yes’ (i.e. total of ‘1/yes’ scores for each category; response range = 0–5) (Supplementary Material 3).

Results

Study characteristics

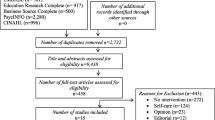

The PRISMA flow chart demonstrates the flow of studies (Fig. 1). Database searches yielded a total of 3140 citations. Citation searching yielded 20 results. After duplicates were removed, 430 full text studies were analysed, and a further 395 were excluded. Eleven of the 20 hand searched studies were excluded. Systematic reviews were set aside for referencing yet excluded from the searches due to duplication of included studies. A total of 46 studies were included in this scoping review and were from the USA, Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, Sweden, South Africa, China, Hong Kong and Singapore.

Most studies were conducted in primary healthcare settings (n = 25) (Supplementary Material 2). Other SLC took place in hospitals (Bird et al., 2022; Burgess & Roberts, 2022; Janson et al., 2009; Meek et al., 2013; Reumerman et al., 2021, 2022; Sultan et al., 2022), at home visits (Bird et al., 2022; Liang En et al., 2011; Ng et al., 2020; Rock et al., 2014; Sarovich et al., 2022; Seymour & Cannon, 2010), via telehealth (Fung et al., 2022; Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Leung et al., 2012; Meuser et al., 2022; Walker et al., 2022), in churches (Gortney et al., 2018; Johnston et al., 2019, 2020), in nursing homes (Dacey et al., 2010; Krout et al., 2010) mobile clinics (Palma et al., 2020), community housing (Busen, 2014; Howell et al., 2021; Krout et al., 2010), detention centres (Shekar et al., 2020), public spaces (Bird et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2015; Sarovich et al., 2022) and pre-schools (Sargison et al., 2021). Nine studies were conducted in more than one setting (Bird et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2015; Busen, 2014; Dacey et al., 2010; Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Krout et al., 2010; Leung et al., 2012; Liang En et al., 2011; Sarovich et al., 2022) (Supplementary Material 2).

As shown by Supplementary Material 2, interprofessional education was implemented before, during and after students delivered health services. Students from two or more disciplines worked together or participated in one or more of the following activities: preparing patient educational material, designing exercise classes, attending lectures, attending practical tutorials or role-play sessions, presenting about a topic to peers and faculty, orientation, shadowing senior students or being mentored by them, conducting patient assessments, delivering group or individual treatment sessions, meeting to plan and evaluate sessions, and co-designing the clinic with faculty staff.

Services offered to patients at interprofessional SLC included individual therapy, group therapy, vaccinations, client assessments, health screening, education, medication review, welfare assistance, equipment prescription and health referrals (Supplementary Material 2).

Methodological quality

Quality appraisal results are presented in Supplementary Material 3. Studies used a variety of designs, including qualitative (Bird et al., 2022; Burgess & Roberts, 2022; Garavelis et al., 2023; Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Johnston et al., 2020; Meuser et al., 2022; Sargison et al., 2021; Sarovich., et al. 2022; Walker et al., 2022), quantitative RCT (Reumerman et al., 2022; Rock et al., 2014; Sultan et al., 2022), quantitative non-RCT (Brown et al., 2015; Janson et al., 2009; Lawrence et al., 2015; Ouyang et al., 2013; Virtue et al., 2018), quantitative descriptive (Asanad et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2021; Danhausen et al., 2015; Gortney et al., 2018; Hu & Leung, 2016; Johnston et al., 2019; Kahkoska et al., 2018; Kent & Keating, 2013; Kent et al., 2016; Krout et al., 2010; Ng et al., 2020; Palma et al., 2020; Peluso et al., 2014; Rowe et al., 2021; Shekar et al., 2020; Sheu et al., 2010), and mixed methods (Beckman et al., 2022; Busen, 2014; Dacey et al., 2010; Felder-Heim & Mader, 2020; Fröberg et al., 2018; Fung et al., 2022; Howell et al., 2021; Leung et al., 2012; Liang En et al., 2011; Meek et al., 2013; Reumerman et al., 2021; Sealey et al., 2017; Seymour & Cannon, 2010).

Twenty-one (46%) studies satisfied all five appraisal criteria of the appropriate category of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, with the remaining studies satisfying four appraisal criteria (13 studies, 28%), three (6 studies, 13%), two (3 studies, 6%) and one appraisal criterion (2 studies, 4%). One study scored zero. The mean number of quality indicators with satisfied criteria was 4 (range 0 to 5) (Supplementary Material 3). Quantitative non-RCT studies received the highest quality ratings within the category (i.e., a score of four or five out of five) (4 out of 5 studies, 80%), followed by qualitative designs (7 out of 9 studies, 78%), mixed methods (10 out of 13 studies, 77%), quantitative descriptive (12 out of 16 studies, 75%) and quantitative RCTs (2 out of 3 studies, 67%). This reflects the use of mostly sound methodological approaches, interventions and interpretation of results based on data collected. Importantly, data from controlled (Brown et al., 2015; Janson et al., 2009; Lawrence et al., 2015; Ouyang et al., 2013; Reumerman et al., 2022; Rock et al., 2014; Sultan et al., 2022; Virtue et al., 2018) and less rigorous designs pointed in the same direction, with mostly positive patient and student outcomes (Supplementary Material 4 and 5).

Outcome measures

Patient outcome measures

As seen in Supplementary Material 4, all studies reported data for patient outcomes. Patient outcomes were determined from self-reported surveys and questionnaires (27 studies), interviews and focus groups (8 studies) and clinical tests (14 studies). Twenty-six surveys or questionnaires were used to investigate patient outcomes and 14 of these were validated tools (Supplementary Material 4). Self-reported measures related to health knowledge, satisfaction with the interventions received or experiences of attending student clinics (Asanad et al., 2018; Beckman et al., 2022; Busen, 2014; Dacey et al., 2010; Fröberg et al., 2018; Fung et al., 2022; Gortney et al., 2018; Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Howell et al., 2021; Kent & Keating, 2013; Kent et al., 2016; Krout et al., 2010; Lawrence et al., 2015; Leung et al., 2012; Liang En et al., 2011; Meek et al., 2013; Meuser et al., 2022; Ng et al., 2020; Ouyang et al., 2013; Palma et al., 2020; Rock et al., 2014; Rowe et al., 2021; Sealey et al., 2017; Seymour & Cannon, 2010; Shekar et al., 2020; Virtue et al., 2018; Walker et al., 2022). The findings are presented in the thematic analysis below.

Patient clinical outcomes often pertained to body weight (Brown et al., 2015; Sealey et al., 2017), blood pressure/ heart rate (Felder-Heim & Mader, 2020; Janson et al., 2009; Johnston et al., 2019; Sealey et al., 2017), chronic disease status (Kahkoska et al., 2018; Janson et al., 2009), medication (Johnston et al., 2019; Reumerman et al., 2021; Sultan et al., 2022) or vaccination (Brown et al., 2021; Sheu et al., 2010). Two functional outcome measures were reported: (i) number of steps determined from a pedometer (Sealey et al., 2017) (ii) scores on the Physical Performance Test (Seymour & Cannon, 2010).

Student Outcome measures

Eighteen studies reported student outcomes (Supplementary Material 5) using validated self-reported measures such as surveys and questionnaires (Dacey et al., 2010; Fröberg et al., 2018; Howell et al., 2021; Janson et al., 2009; Liang En et al., 2011; Ng et al., 2020; Sealey et al., 2017), non-validated self-reports (Busen, 2014; Fung et al., 2022; Krout et al., 2010; Liang En et al., 2011; Meuser et al., 2022; Reumerman et al., 2021; Sealey et al., 2017; Seymour & Cannon, 2010), and interviews or focus groups (Beckman et al., 2022; Bird et al., 2022; Sealey et al., 2017; Walker et al., 2022). The most common validated measures used were the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale and the Fund for the Improvement of Post-Secondary Education Survey Instrument (Supplementary Material 5).

Clinical Educator Outcome measures

Only three investigations reported clinical educator outcomes. Data collection methods included interviews (Beckman et al., 2022; Bird et al., 2022; Fröberg et al., 2018) and a non-validated self-reported survey (Beckman et al., 2022).

Thematic analysis

Patient views on interprofessional student led clinics

Our qualitative analyses of patient views yielded three key themes about interprofessional student led clinics (Table 1 and Supplementary Material 4).

Improving personal health and health knowledge

Patients reported satisfaction with the knowledge and information gained from attending student led interprofessional clinics, with most reporting improved understanding of their own health and wellbeing (Burgess & Roberts, 2022; Busen, 2014; Danhausen et al., 2015; Fung et al., 2022; Garavelis et al., 2023; Gortney et al., 2018; Howell et al., 2021; Kent et al., 2016; Ng et al., 2020). They appreciated students giving clear explanations and advice on topics such as exercise (Howell et al., 2021), managing COVID19 (Fröberg et al., 2018), tobacco cessation (Virtue et al., 2018), prenatal care (Danhausen et al., 2015), personal hygiene (Gortney et al., 2018; Sealey et al., 2017) and how to minimise hospital readmissions (Seymour & Cannon, 2010). Having their questions answered was a key reason for strong patient satisfaction (Busen, 2014; Kent & Keating, 2013; Lawrence et al., 2015; Palma et al., 2020) (Supplementary Material 4).

Patients also reported learning about how to monitor their own health and wellbeing (Supplementary Material 4) (Busen, 2014; Dacey et al., 2010; Danhausen et al., 2015; Felder-Heim & Mader, 2020; Leung et al., 2012; Liang En et al., 2011; Rock et al., 2014; Sealey et al., 2017). They valued the ways in which SLC fostered health promotion (Dacey et al., 2010; Howell et al., 2021; Kent & Keating, 2013; Leung et al., 2012; Reumerman et al., 2021; Sealey et al., 2017; Seymour & Cannon, 2010), healthy aging (Dacey et al., 2010; Howell et al., 2021; Sarovich et al., 2022) and healthy lifestyle choices (Howell et al., 2021; Leung et al., 2012; Sealey et al., 2017). This empowered patients to change their health behaviours and to recognise when their health was changing (Burgess & Roberts, 2022; Busen, 2014).

“It has woke [sic] me up and think that actually each one of these things is part of my health and I need to update it all the time, I need to stay on top of my exercise, I need to stay on top of my healthy eating, I need to go to the dentist, I need to get my prostate checked, I need to do all of these to keep rolling forward.” (Sealey et al., 2017, pg. 1137).

Patients advised health benefits from frequent health screening (Danhausen et al., 2015; Felder-Heim & Mader, 2020; Leung et al., 2012; Liang En et al., 2011; Rock et al., 2014). Many appreciated person-centred, multi-disciplinary care (Burgess & Roberts, 2022; Liang En et al., 2011; Sargison et al., 2021). Many patients were diagnosed with new conditions or received treatment for existing conditions such as cardiovascular disease (Gortney et al., 2018; Johnston et al., 2019, 2020), respiratory infections (Danhausen et al., 2015; Gortney et al., 2018; Johnston et al., 2019, 2020; Rock et al., 2014), infectious diseases (Danhausen et al., 2015; Johnston et al., 2019, 2020), or dental problems (Busen, 2014; Johnston et al., 2020) (Supplementary Material 4).

As shown in Supplementary Material 4, several authors reported improvements in patient bodyweight (Brown et al., 2015; Leung et al., 2012), blood pressure (Felder-Heim & Mader, 2020; Rowe et al., 2021), cholesterol levels (Janson et al., 2009), smoking (Virtue et al., 2018), diabetes (Kahkoska et al., 2018; Rowe et al., 2021), and medication adherence (Leung et al., 2012; Rock et al., 2014). Many patients had their medications reviewed, changed or prescribed in the student led clinics (Kent & Keating, 2013; Kent et al., 2016; Leung et al., 2012; Liang En et al., 2011; Ng et al., 2020; Peluso et al., 2014; Reumerman et al., 2021, 2022; Rowe et al., 2021; Sultan et al., 2022; Virtue et al., 2018). Some received medications or vaccinations for free or at a low-cost (Asanad et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2021; Johnston et al., 2019; Ouyang et al., 2013; Palma et al., 2020; Sheu et al., 2010). Referrals to other services, such as emergency departments and community health centres, were made by many clinics (Asanad et al., 2018; Danhausen et al., 2015; Gortney et al., 2018; Hu & Leung, 2016; Janson et al., 2009; Johnston et al., 2019, 2020; Kent & Keating, 2013; Kent et al., 2016). Student led clinics reduced hospital admissions and emergency department use for some patients (Janson et al., 2009; Rock et al., 2014; Rowe et al., 2021).

Patients valued services received from interprofessional student teams

Supplementary Material 4 shows that most patients reported positive experiences with SLC (Bird et al., 2022; Fung et al., 2022; Garavelis et al., 2023; Gortney et al., 2018; Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Kent et al., 2016; Lawrence et al., 2015; Liang En et al., 2011; Sargison et al., 2021; Sarovich et al., 2022). They felt respected, understood and listened to by students (Fröberg et al., 2018; Garavelis et al., 2023; Howell et al., 2021; Johnston et al., 2020; Kent et al., 2016; Krout et al., 2010; Liang En et al., 2011; Sargison et al., 2021; Sarovich et al., 2022).

“The experience was very good, very accurate, and very attentive, they knew what they were doing, there was little confusion between what was happening…the reporting and the questioning was done very thoroughly and covered a lot of stuff and they listened and understood what I was explaining” (Garavelis et al., 2023, pg. 6).

The value of social interactions with students, peers and clinical supervisors was also noted by patients (Burgess & Roberts, 2022; Fung et al., 2022; Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Howell et al., 2021; Krout et al., 2010; Ng et al., 2020; Sarovich et al., 2022) (Supplementary Material 2). For some it was the most enjoyable aspect of participating (Seymour & Cannon, 2010).

“The interaction with my peers [was most valuable], because I learned that I am loved and wanted.” (Howell et al., 2021, pg. 259).

In general, patients enjoyed the contact with young people and meeting others with similar health conditions (Fung et al., 2022; Howell et al., 2021). Participants at a remote indigenous community valued the potential to share cultural knowledge with future generations through their connections with students (Sarovich et al., 2022).

“When you guys learn [here, you] also learn a different culture too, to pass on to like, the next community go and do this with the Elders…” (Sarovich et al., 2022, pg. 5).

Longer appointment times were appreciated (Fröberg et al., 2018; Johnston et al., 2020; Kent & Keating, 2013; Kent et al., 2016; Ng et al., 2020), although some patients commented on home visits being too long or too short (Ng et al., 2020). Excessive waiting times were also noted by some patients (Asanad et al., 2018; Lawrence et al., 2015).

Improving access to healthcare for underserved people

Student-run free clinics often provided services for patients who were unable to access healthcare from government agencies or via other means (Asanad et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2021; Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Johnston et al., 2020) (Supplementary Material 4). This particularly applied to homeless people, who struggled to maintain a healthy lifestyle when living on the streets (Johnston et al., 2020). Many experienced theft, poor hygiene, exposure to the elements and diseases (Asanad et al., 2018; Johnston et al., 2020).

“During winter it’s whereby we experience a high number of death rates on the street, due to the fact that people, they don’t know their health state.” (Johnston et al., 2020, pg. 4).

Some patients reported barriers to access healthcare, such as the cost of transport and comorbidities (Johnston et al., 2019; Peluso et al., 2014). Sometimes health insurance was not affordable or available, due to immigration status or the country of residence (Asanad et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2021; Peluso et al., 2014). Student clinics were the main source of healthcare for many underserved groups and helped to address some of these issues (Asanad et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2021; Palma et al., 2020; Sarovich et al., 2022). Some homeless people reported a preference for services to be more frequent, such as dental, social and psychology services.

Student outcomes in interprofessional student led clinics

As shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Material 5, six main themes emerged.

Improving teamwork

Students valued the opportunity to work in teams (Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Howell et al., 2021; Krout et al., 2010; Liang En et al., 2011) (Supplementary Material 5). Interprofessional teams helped them to develop mutual respect (Bird et al., 2022; Dacey et al., 2010), confidence and preparedness for future clinical practice (Beckman et al., 2022; Ng et al., 2020; Reumerman et al., 2021). Students who held leadership positions gained a better understanding of collaborative practice (Liang En et al., 2011). The importance of input from a range of disciplines in patient care was noted:

“The knowledge from psychology is a little bit different to counselling, and then you have… social work [with] more… resources, and I think it’s just really powerful having the combination of the different professions.” (Beckman et al., 2022, pg. 99).

Acquiring and applying knowledge

Students reported gaining knowledge in four key areas: scope of practice, healthcare needs of older people, patient-centred care and practice management and administration. Improved knowledge about their scope of practice and the role of other professionals in the team was particularly valued (Bird et al., 2022; Busen, 2014; Howell et al., 2021; Reumerman et al., 2021; Sealey et al., 2017; Seymour & Cannon, 2010). Some students realised how little they knew about the role of others, as well as how this changed through participation:

“I looked up the scope of practice for nurse practitioners…it was interesting to read what my scope would be and try and explain it to other disciplines. After class…it was interesting to hear how other professions viewed us.” (Busen, 2014, pg. 364).

Knowledge acquired from working with older adults was noted. Some students felt that they acquired an improved understanding of the needs of vulnerable older people, especially when they had limited healthcare resources in the community (Dacey et al., 2010; Fung et al., 2022; Howell et al., 2021; Ng et al., 2020; Seymour & Cannon, 2010).

“I have learned that seniors do want to be actively engaged, and appreciate the opportunity to learn new things that will benefit them…. Working with seniors is a unique challenge, because it can be difficult to look at things from their perspective….” (Dacey et al., 2010, pg. 698).

Knowledge of patient-centred care enabled some students to identify the impact of health conditions on the ability of people to perform activities of daily living (Bird et al., 2022; Seymour & Cannon, 2010). It was reported that real-life clinical experiences acquired in an interprofessional setting helped them to develop a holistic approach to healthcare (Bird et al., 2022; Dacey et al., 2010; Fröberg et al., 2018).

Many students participated in free clinics delivered by an interprofessional student council, where student leaders oversaw the logistical and administrative tasks of the clinic (Asanad et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2021; Busen, 2014; Danhausen et al., 2015; Gortney et al., 2018; Liang En et al., 2011; Ouyang et al., 2013; Palma et al., 2020; Peluso et al., 2014; Reumerman et al., 2022; Sheu et al., 2010; Sultan et al., 2022). This assisted them to develop leadership skills, and experience in service design and service implementation (Danhausen et al., 2015; Liang En et al., 2011). Students also learned about administration and clinic management:

“NHS is the best volunteer program out there because it is initiated by students, done by students, and supported by everyone else. I was placed in charge of a team, and it was wonderful to have the opportunity to guide my juniors along, as well as take charge of handling the patient’s care.” (Liang En et al., 2011, pg. 834).

Improving communication skills

Most students reported improvements in their communication skills. Rapport building with patients, educators and other students also improved (Bird et al., 2022; Howell et al., 2021; Leung et al., 2012; Meuser et al., 2022) (Table 2 and Supplementary Material 5). This was particularly true when orientation was delivered prior to service (Bird et al., 2022; Meuser et al., 2022). Clinics delivered via telehealth helped students to develop their technology and management skills (Meuser et al., 2022; Walker et al., 2022). A number of students reported improvements in public speaking skills (Howell et al., 2021; Sealey et al., 2017). Improved communication was linked to service quality and efficiency:

“…I learned how really utilizing all professions can improve patient outcomes. I also learned that through good communication skills and respect for all health care professions we can accomplish higher quality work in a timelier manner.” (Dacey et al., 2010, pg. 698).

Valuing participation in student teams

Most students found that the interprofessional clinic environment provided a valuable team experience (Fröberg et al., 2018; Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Krout et al., 2010; Reumerman et al., 2021). Some saw direct relevance to the content about teamwork learned in class (Krout et al., 2010) and to future practice (Beckman et al., 2022). Support and trust gave them increased confidence and autonomy with teamwork and patient care (Bird et al., 2022; Dacey et al., 2010).

“During this project I have learned many things about myself as well as my team members…. I have learned to become more adaptable which will help me to overcome obstacles in my profession. Also, I strongly believe that the key to success and being able to overcome any barrier we are presented with is the ability to stay confident and always remain optimistic. This class has given me the confidence and optimism necessary to overcome any problem”. (Dacey et al., 2010. pg. 698)

Increasing social awareness

Many students gained more positive perceptions about working with older adults during the clinics (Table 2 and Supplementary Material 5). Some changed their negative preconceived ideas about the capabilities and interests of older people (Meuser et al., 2022; Ng et al., 2020).

“This class will definitely be a memorable experience that will forever have an impact on both my personal and professional life. I can honestly say my learnings from this class have definitely changed my views toward the aging population.” (Howell et al., 2021, pg. 260).

Working with underserved groups was also appreciated by students and benefited altruism (Busen, 2014; Howell et al., 2021; Liang En et al., 2011). The clinics facilitated cultural competence (Bird et al., 2022), especially when providing services to marginalised groups (Bird et al., 2022; Busen, 2014; Danhausen et al., 2015). Skills in identifying healthcare gaps were noted:

“The NHS program is helpful in exposing us as students to the poor living conditions and health knowledge of residents in Taman Jurong. Hopefully it also helps the patients by picking up otherwise undetected diseases and reintegrating patients who have fallen out of the health care system.” (Liang En et al., 2011, pg. 835).

Student views of challenges

Having a poor understanding of the role of other health professionals at the start of the clinical placement was challenging for some students (Beckman et al., 2022; Bird et al., 2022; Busen, 2014; Sealey et al., 2017) (Tables 2 and Supplementary Material 5). Several requested more orientation and role-play prior to the clinic (Beckman et al., 2022; Howell et al., 2021). A small number of difficulties were reported in telehealth clinics related to rapport building with patients (Fung et al., 2022; Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Leung et al., 2012; Walker et al., 2022). A number required more training in online service delivery:

“So if it was to be a known—say telehealth placement—it would be interesting to learn some of those communication strategies that you always—at uni you’re learning face to face, you’re trying to learn how to build rapport and all of that physical, body language, stuff like that. So I think it could have been beneficial to know that going in to be a bit more prepared.” (Walker et al., 2022, pg. 86).

Clinical educator views in interprofessional student led clinics

Three main themes emerged from qualitative analysis of clinical educator interviews (Table 3 and Supplementary Material 6).

Facilitating the clinical educator role

The clinical educator role was found to be facilitated in interprofessional SLC by allocating sufficient time for clinical supervision (Table 3 and Supplementary Material 6):

“I believe that I have more time to engage in my role… even if you always try to but it is… it is different. It is quieter and I have more time to engage in the subject, I have time to look things up before so that I know what they are studying and what they are supposed to focus on and so forth.” (Fröberg et al., 2018, pg. 42).

Regular meetings with stakeholders and students also enabled collaboration (Bird et al., 2022; Fröberg et al., 2018) and educators saw modelling and communication as beneficial outcomes:

“I will go in and have a chat, even if it’s just “Hey, this is what I’m thinking, what do you reckon?” I think modelling that behaviour is a great approach.” (Beckman et al., 2022, pg. 101).

Understanding roles, responsibilities and value of interprofessional teams

Clinical educators noticed the value of interprofessional SLC in boosting student confidence to work within a team, mostly due to improved knowledge of their own scope of practice, the role of others and improved communication skills (Bird et al., 2022; Fröberg et al., 2018). Student-centred supervision gave students more independence and responsibilities with patients (Fröberg et al., 2018).

“I think their professional growth was enormous…they really grew in their ability.” (Bird et al., 2022, pg. 82).

With regards to interprofessional supervision training, SLC provided a conducive environment for supervision and afforded opportunities for student-centred feedback (Beckman et al., 2022; Fröberg et al., 2018).

“I have to say that there is much less stress at the SRC…one gets to focus on the supervisor role.” (Fröberg et al., 2018, pg. 42) (SRC = student run clinic).

The interprofessional setting promoted student learning (Beckman et al., 2022; Bird et al., 2022).

“Because working in unison, apart from anything else, can help them understand the life of the people they were working with. And really shift their thinking from a disability or a therapy focus, to a community empowerment focus.” (Bird et al., 2022, pg. 80).

Challenges in delivery

Educators identified some procedural issues in running the interprofessional clinics (Beckman et al., 2022; Fröberg et al., 2018) (Table 3 and Supplementary Material 6). Sometimes it was difficult to align the timetables of students from different professions, particularly when different groups of students required orientation on the same day (Beckman et al., 2022). A few lacked necessary training and needed further professional development and orientation prior to supervising students in the clinics (Fröberg et al., 2018). Supervisors noted that some students lacked awareness of their own professional culture, which may have been a barrier in developing strong connections with other students, staff and the community (Bird et al., 2022). Some supervisors acknowledged the balance between student autonomy and supervisor control was challenging (Fröberg et al., 2018).

“Then again it’s about control… And I guess that you are different about that and I believe that me as a person, I like to be in control. So you really need to challenge yourself, and at the same time you need to find that balance. So that it is still patient safe and, well. That is it, the difficult part. And sometimes you are in a good flow and sometimes it is more difficult…” (Fröberg et al., 2018, pg. 43).

Feasibility and implementation

Feasibility is summarised in Table 4. Clinics were viable provided that there was adequate patient access, technical resources, equipment, infrastructure and availability of well trained clinical education staff (Table 4). Dedicated clinic funding and marketing increased the feasibility of interprofessional student led clinics (Table 4).

Thirty studies reported barriers and facilitators to student clinic operations (Asanad et al., 2018; Bird et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2021; Busen, 2014; Dacey et al., 2010; Danhausen et al., 2015; Felder-Heim & Mader, 2020; Fröberg et al., 2018; Fung et al., 2022; Gortney et al., 2018; Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Howell et al., 2021; Hu & Leung, 2016; Janson et al., 2009; Kahkoska et al., 2018; Kent et al., 2016; Krout et al., 2010; Leung et al., 2012; Meek et al., 2013; Ouyang et al., 2013; Palma et al., 2020; Peluso et al., 2014; Reumerman et al., 2022; Rowe et al., 2021; Sargison et al., 2021; Sarovich et al., 2022; Sealey et al., 2017; Shekar et al., 2020; Sheu et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2022) (Table 4).

Frequently cited facilitators were (i) delivery of student orientation prior to student clinics (Beckman et al., 2022; Bird et al., 2022; Danhausen et al., 2015; Howell et al., 2021; Lawrence et al., 2015; Meuser et al., 2022; Ouyang et al., 2013; Sargison et al., 2021) (ii) consistent and positive support from educators (Bird et al., 2022; Dacey et al., 2010; Fröberg et al., 2018; Sealey et al., 2017; Seymour & Cannon, 2010; Sheu et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2022) and (iii) use of existing clinics (Bird et al., 2022; Dacey et al., 2010; Danhausen et al., 2015; Fröberg et al., 2018; Janson et al., 2009; Reumerman et al., 2022).

Frequently cited barriers were difficulty timetabling students from different disciplines (Beckman et al., 2022; Busen, 2014; Dacey et al., 2010; Danhausen et al., 2015; Gortney et al., 2018; Howell et al., 2021; Janson et al., 2009), low University support (Asanad et al., 2018; Beckman et al., 2022; Fröberg et al., 2018; Gortney et al., 2018; Henderson-Kalb et al., 2022; Krout et al., 2010; Meek et al., 2013; Rowe et al., 2021) and poor funding (Asanad et al., 2018; Danhausen et al., 2015; Leung et al., 2012; Sheu et al., 2010).

Discussion

Student led clinics are increasingly being used to prepare students for the demands of future workforce requirements (Guitar & Connelly, 2021; Hopkins et al., 2022; Schutte et al., 2015). This review has generated new evidence that interprofessional SLC can have benefits for patients, students and clinical educators. Many patients reported a positive impact on health, knowledge, social interactions, or clinical outcomes. There was converging evidence that students felt better prepared for working in teams, taking responsibility for service delivery and providing client-centred care. Clinical educators highlighted the benefits of interprofessional supervision to student learning outcomes.

Over and above the previous reviews by Hopkins et al. (2022) and Schutte et al. (2015), our article adds new evidence on the benefits to patients participating in interprofessional SLC. Patient access to healthcare services was facilitated, particularly when clinics were delivered in the community (Bird et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2021; Howell et al., 2021), schools (Sargison et al., 2021), workplaces (Brown et al., 2015) and aged care (Busen, 2014). Extended time for consultations was valued by patients as it facilitated rapport building and enabled patients to feel listened to (Fröberg et al., 2018; Garavelis et al., 2023). This is in agreement with the work of Lemon et al. showing that consultation length plays an important role in patient satisfaction (Lemon & Smith, 2014). Improvements in patient personal health and health knowledge were also consistently demonstrated across the studies that we reviewed, in agreement with previous reports (Broman et al., 2022; Frakes et al., 2011; Suen et al., 2020).

Student learning outcomes were enhanced by interprofessional SLC, especially knowledge of professional roles, clinical skills and teamwork (Beckman et al., 2022; Bird et al., 2022; Dacey et al., 2010; Danhausen et al., 2015; Fung et al., 2022; Howell et al., 2021; Janson et al., 2009; Krout et al., 2010; Liang En et al., 2011; Ng et al., 2020; Reumerman et al., 2021; Sealey et al., 2017; Seymour & Cannon, 2010). These findings agree with Wilson et al. (2023) who reported that students enhanced their collaboration skills and empathy for vulnerable populations. Students also valued the feedback received from clinical educators (Fröberg et al., 2018; Sealey et al., 2017). This concurred with a report by Lie et al. (2016) who advocated for timely and relevant feedback to assist students to integrate their clinical skills. Students who received prior training on their role in the team had more positive experiences (Beckman et al., 2022; Bird et al., 2022).

Clinical educators noted an increased sense of student responsibility and preparedness for future practice (Beckman et al., 2022; Bird et al., 2022). The educators themselves gained knowledge and refined their collaborative skills (Fröberg et al., 2018). Similar findings were reported by Martin et al. (2022) who showed that clinical educators at rural SLC improved their interprofessional competencies. Some clinical educators felt unprepared for interprofessional supervision (Fröberg et al., 2018), a finding previously identified by Anderson et al. (2009). Improvements in confidence and skills were reported by educators who took part in training prior to involvement in interprofessional SLC (Anderson et al., 2009; Bird et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2015; Busen, 2014; Fung et al., 2022).

In agreement with other research, we found the benefits of interprofessional SLC also included a focus on health promotion (Dacey et al., 2010; Kent & Keating, 2013), genuine opportunities for interprofessional learning (Bird et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2021; Fung et al., 2022; Janson et al., 2009; Reumerman et al., 2022; Seymour & Cannon, 2010), better access to university resources (Asanad et al., 2018; Bird et al., 2022; Danhausen et al., 2015; Garavelis et al., 2023; Sarovich et al., 2022; Sealey et al., 2017) and opportunities for service co-design (Bird et al., 2022; Howell et al., 2021; Krout et al., 2010; Sarovich et al., 2022).

The feasibility of delivering interprofessional SLC was had some limitations and was affected by a range of issues. They were often difficult to timetable (Beckman et al., 2022; Busen, 2014; Dacey et al., 2010) or fund (Asanad et al., 2018; Danhausen et al., 2015; Kent et al., 2016). Some staff and students felt poorly prepared for this unique type of multi-disciplinary clinical placement (Beckman et al., 2022; Busen, 2014; Janson et al., 2009). Kent et al. (2014) observed that financial constraints could be a challenge, as well as staffing (Fröberg et al., 2018; Hu & Leung, 2016; Krout et al., 2010) and venue availability (Fröberg et al., 2018; Howell et al., 2021). Wait times were sometimes associated with dissatisfaction with free clinics (Asanad et al., 2018; Lawrence et al., 2015), a finding shared by others who sought effective strategies to improve efficiency (Lee et al., 2017; Stephens et al., 2020).

This scoping review has some limitations. Some studies were of modest methodological quality and most had comparatively small samples and non-randomized or non-comparative designs which increase the risk of bias (Supplementary Material 2 and 3). Broman et al. (2022) and Wilson et al. (2023) noted that heterogeneity and underpowered samples limit the generalisability of findings in this field. Less than half of studies reported student outcomes, and only a few collected data on clinical educator views. Around half of the studies with patient outcomes used self-reported methods which carry an increased risk of bias. Self-reported measures, while valuable for capturing individual experiences, carry social desirability bias, response bias, and recall bias (Althubaiti, 2016). This increased risk of bias underscores the importance of future investigations adopting robust study designs, with large sample sizes and diverse patient populations, using validated quantitative and qualitative outcome measures. It would also be helpful to compare the outcomes of student led clinics with professional-delivered interventions. Evaluation of long-term student outcomes upon entry to the workforce is also required.

In conclusion, student led health clinics can have positive impacts for student learning, especially in relation to interprofessional collaborative practice, skill development and readiness for entering the workforce. For patients, healthcare access can be facilitated and there are benefits for knowledge, health and wellbeing.

Data availability

All data sets discussed in the current review are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Althubaiti, A. (2016). Information bias in health research: Definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 211–217.

Anderson, E. S., Cox, D., & Thorpe, L. N. (2009). Preparation of educators involved in interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional care, 23(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820802565106

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Asanad, K., Zheng, J., Chan-Golston, A., Tam, E., Bhetraratana, M., Lan, C. W., Zhao, M., Abdi, R., Abdi, F., Vasti, E., & Prelip, M. L. (2018). Assessing quality of care through client satisfaction at an interprofessional student-run free clinic. Journal of Interprofessional care, 32(2), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1395827

Beckman, E. M., Mandrusiak, A., Forbes, R., Mitchell, L., Tower, M., Cunningham, B., & Lewis, P. (2022). A student-led, interprofessional care, community-based healthcare service: Student, clinical educator and client perceptions of interprofessional care and education. Focus on Health Professional Education-a Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(1), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.11157/fohpe.v23i1.476

Bird, K., Stothers, K., Armstrong, E., Marika, E. D., Yunupingu, M. D., Brown, L., Witt, S., Campbell, N., & Barker, R. (2022). Marŋgithirri guŋga’Yunarawu Ga guŋga’yunyarawu marŋgithinyarawu learning to connect and connecting to learn: Preparing the rural and remote allied health workforce through a co-created student-implemented service in East Arnhem, Australia. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 30(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12813

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Briggs, L., & Fronek, P. (2020). Student experiences and perceptions of participation in Student-Led Health clinics: A systematic review. Journal of Social work Education, 56(2), 238–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1656575

Broman, P., Tokolahi, E., Wilson, O. W. A., Haggie, M., Andersen, P., & Brownie, S. (2022). Patient outcomes from Student-Run Health Services: An integrative review. J Multidiscip Healthc, 15, 641–665. https://doi.org/10.2147/jmdh.S348411

Brown, J., Lydecker, J. A., Turner, T., Knackstedt, R. W., & O’Neil, P. M. (2015). A novel approach to training students in delivering evidence-based obesity treatment. Family Medicine, 47(5), 378–382.

Brown, S. H., Fisher, E. L., Taylor, A. Q., Neuzil, K. E., Trump, S. W., Sack, D. E., Fricker, G. P., & Miller, R. F. (2021). Influenza vaccine community outreach: Leveraging an interprofessional healthcare student workforce to immunize marginalized populations. Preventive Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106460., 147, N.PAG-N.PAG.

Buckley, E., Vu, T., & Remedios, L. (2014). The REACH project: Implementing interprofessional practice at Australia’s first student-led clinic. Educ Health (Abingdon), 27(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.134360

Burgess, A., & Roberts, C. (2022). Interprofessional student-led clinics: The volunteer patient experience. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03760-6

Busen, N. H. (2014). An interprofessional education project to address the health care needs of women transitioning from prison to community reentry. Journal of Professional Nursing: Official Journal of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 30(4), 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.01.002

Covidence systematic review software Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

Dacey, M., Murphy, J. I., Anderson, D. C., & McCloskey, W. W. (2010). An Interprofessional Service-Learning Course: Uniting students across Educational levels and promoting patient-centered care. Journal of Nursing Education, 49(12), 696–699. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20100831-09

Danhausen, K., Joshi, D., Quirk, S., Miller, R., Fowler, M., & Schorn, M. N. (2015). Facilitating Access to prenatal care through an Interprofessional Student-Run Free Clinic. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 60(3), 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12304

Davis, L. (2021). Utilization of health and non-health major interdisciplinary teams in an undergraduate nursing faculty-student run community wellness clinic setting. Journal of Professional Nursing, 37(1), 108–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.07.002

Felder-Heim, C., & Mader, K. (2020). Quality of diabetes and Hypertension Management at the DAWN (dedicated to Aurora’s Wellness and needs) Student-Run Free Clinic. Cureus, 12(8), e9539. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9539

Forbes, R., Beckman, E., Tower, M., Mandrusiak, A., Mitchell, L. K., Sexton, C. T., Cunningham, B., & Lewis, P. A. (2021). Interprofessional, student-led community health clinic: Expanding service provision and clinical education capacity. Australian Health Review, 45(2), 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH20021

Frakes, K. A., Tyzack, Z., Miller, M., Davies, L., Swanston, A., & Brownie, S. (2011). The Capricornia Project: Developing and implementing an interprofessional student-assisted allied health clinic.

Fröberg, M., Leanderson, C., Fläckman, B., Hedman-Lagerlöf, E., Björklund, K., Nilsson, G. H., & Stenfors, T. (2018). Experiences of a student-run clinic in primary care: A mixed-method study with students, patients and supervisors. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 36(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02813432.2018.1426143

Fung, M. Y., Lee, Y. H., Lee, Y. T. A., Wong, M. L., Li, J. T. S., Ng, N., E. E., & Lee, V. W. Y. (2022). Feasibility of a telephone-delivered educational intervention for knowledge transfer of COVID-19-related information to older adults in Hong Kong: A pre–post-pilot study. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 8(1), 1–11.

Garavelis, K. N., Hayes, N., Rose, T. A., Maloney, M., Liddle, K., Moritz, K., Gullo, M., Gullo, H. L., McMah, R., Heussler, H., & Reid, N. (2023). Exploring the experience of service users following attendance at a student-led interprofessional neurodevelopmental clinic. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2023.2193430

Gortney, J., Mendez, J., Bowers, C., Appel, J., Blanks, D., & Cheung, W. L. (2018). Patient assessment of engagement with students in an interprofessional student-run free clinic for individuals experiencing homelessness. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 27(1), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2017.1421871

Guitar, N. A., & Connelly, D. M. (2021). A systematic review of the Outcome measures used to Evaluate Interprofessional Learning by Health Care Professional Students during Clinical experiences. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 44(3), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278720978814

Gustafsson, L., Hutchinson, L., Theodoros, D., Williams, K., Copley, A., Fagan, A., & Desha, L. (2016). Healthcare students’ experiences of an interprofessional, student-led neuro-rehabilitation community-based clinic. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(2), 259–261. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1086730

Haggarty, D., & Dalcin, D. (2014). Student-run clinics in Canada: An innovative method of delivering interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional care, 28(6), 570–572. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.916658

Hall, M., McFarlane, L. A., & Mulholland, S. (2012). Positive clinical placements: Perspectives of students and clinical educators in rehabilitation medicine. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 19(10), 549–556. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2012.19.10.549

Hayward, L. M., Meleis, W., Mahanna, J., & Ventura, S. H. (2016). Interprofessional collaboration among physical therapy, Speech-Language Pathology, and Engineering Faculty and students to address Global Pediatric Rehabilitation needs: A Case Report. Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 30(4), 24–34. https://journals.lww.com/jopte/Fulltext/2016/30040/Interprofessional_Collaboration_Among_Physical.5.aspx

Henderson-Kalb, J. R., Berg-Weger, M., Ramel, M., Fitzgerald, J., Hawthorne, K., & Vaughn, A. (2022). A student-led Geriatric Assessment Clinic: Interprofessional education with an older adult population. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2022.2142577

Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., & O’Cathain, A. (2018). The mixed methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291.

Hopkins, S., Bacon, R., & Flynn, A. (2022). Student outcomes for interprofessional education in student led clinics: A rapid review. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 36(2), 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1858767

Horbal, S. R., Grice, B. A., Evans, A., Kaplan, K. W., Wright, L., Bidulescu, A., & Pfeifle, A. L. (2019). Outcomes from a single-intervention trial to improve interprofessional practice behaviors at a student-led free clinic. Journal of Interprofessional Education and Practice, 17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2019.100285

Howell, B. M., Redmond, L. C., & Wanner, S. (2021). I learned that I am loved: Older adults and undergraduate students mutually benefit from an interprofessional service-learning health promotion program. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 42(2), 252–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2020.1791104

Hu, T., & Leung, F. H. (2016). An evaluation of wait-times at an interprofessional student-run free clinic. Journal of Interprofessional care, 30(4), 532–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1181614

Huang, K., Maleki, M., Regehr, G., & McEwen, H. (2021). Examining the Educational Value of Student-Run Clinics for Health Care Students. Academic Medicine, 96(7), 1021–1025. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003922

Isaacson, J. H., Neides, D., Mayer, M., & Nottingham, K. (2014). Patient perceptions of having 1st- and 2nd-year medical students involved in their care. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 26(2), 164–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2014.883988

Janson, S. L., Cooke, M., McGrath, K. W., Kroon, L. A., Robinson, S., & Baron, R. B. (2009). Improving chronic care of type 2 diabetes using teams of interprofessional learners. Academic Medicine, 84(11), 1540–1548. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bb2845

Johnston, D., McInerney, P., & Miot, J. (2019). A Profile of the Health of Homeless at an Inner City Primary Health Care Clinic in South Africa. Journal of Health Care for the Poor & Underserved, 30(4), 1455–1466. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2019.0093

Johnston, D., McInerney, P., & Thurling, H. (2020). Experiences of the homeless accessing an inner-city pharmacy and medical student-run clinic in Johannesburg. Health SA, 25, 1358. https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v25i0.1358

Kahkoska, A. R., Brazeau, N. F., Lynch, K. A., Kirkman, M. S., Largay, J., Young, L. A., & Buse, J. B. (2018). Implementation and evaluation of Shared Medical appointments for type 2 diabetes at a Free, Student-Run Clinic in Alamance County, North Carolina. J Med Educ Train, 2(1).

Kent, F., & Keating, J. (2013). Patient outcomes from a student-led interprofessional clinic in primary care. Journal of Interprofessional care, 27(4), 336–338. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.767226

Kent, F., Drysdale, P., Martin, N., & Keating, J. L. (2014). The mixed-Discipline aged-Care Student Clinic: An authentic Interprofessional Learning Initiative. Journal of Allied Health, 43(1), 51–56. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/mixed-discipline-aged-care-student-clinic/docview/1524323470/se-2

Kent, F., Martin, N., & Keating, L., J (2016). Interprofessional student-led clinics: An innovative approach to the support of older people in the community. Journal of Interprofessional care, 30(1), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1070133

Krout, J. A., Bergman, E., Bianconi, P., Caldwell, K., Dorsey, J., Durnford, S., Erickson, M. A., Lapp, J., Monroe, J. E., Pogorzala, C., & Taves, J. V. (2010). Intergenerational service learning with elders: Multidisciplinary activities and outcomes. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 31(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960903578329

Lawrence, D., Bryant, T. K., Nobel, T. B., Dolansky, M. A., & Singh, M. K. (2015). A comparative evaluation of patient satisfaction outcomes in an interprofessional student-run free clinic. Journal of Interprofessional care, 29(5), 445–450. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2015.1010718

Lee, J. S., Combs, K., & Pasarica, M. (2017). Improving efficiency while improving patient care in a student-run free clinic. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 30(4), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2017.04.170044

Lemon, T. I., & Smith, R. H. (2014). Consultation Content not Consultation length improves patient satisfaction. J Family Med Prim Care, 3(4), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.148102

Lestari, E., Stalmeijer, R. E., Widyandana, D., & Scherpbier, A. (2016). Understanding students’ readiness for interprofessional learning in an Asian context: A mixed-methods study. Bmc Medical Education, 16, 179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0704-3

Leung, L. B., Busch, A. M., Nottage, S. L., Arellano, N., Glieberman, E., Busch, N. J., & Smith, S. R. (2012). Approach to Antihypertensive Adherence: A feasibility study on the Use of Student Health coaches for uninsured hypertensive adults. Behavioral Medicine, 38(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2011.651174

Leung, Y. C. G., Soundararajan, A., Ng, W. Q., Lay, W. Q., Lee, S. M., Chew, B. H., Lim, C. Y. S., Wong, S. F., Lim, K. H. C., Wong, C. H., & Koh, G. C. H. (2016). Tri-generational homecare project: The effect of a student-initiated homecare programme on ageism and interpersonal skills among undergraduate healthcare students. Annals of the Academy of Medicine Singapore, 45(9 Supplement 1), S353. http://www.annals.edu.sg/pdf/45VolNo9Sep2016/SHBC2016.pdf

Leung, Y. C. G., Ng, K. Y. Y., Yow, K. S., Ngiam, N. H. W., Yeo, D. G. D., Tey, A. J. Y., Lim, M. S. R., Tang, A. K. W., Chew, B. H., & Tham, C. (2022). Impact of a longitudinal student-initiated home visit programme on interprofessional education. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 7(4), 1.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 1–9.

Liang En, W., Koh, G. C. H., & Lim, V. K. G. (2011). Caring for Underserved patients through Neighborhood Health Screening: Outcomes of a Longitudinal, Interprofessional, Student-Run Home Visit Program in Singapore. Academic Medicine, 86(7), 829–839. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31821d841d

Lie, D. A., Forest, C. P., Kysh, L., & Sinclair, L. (2016). Interprofessional education and practice guide 5: Interprofessional teaching for prequalification students in clinical settings. Journal of Interprofessional care, 30(3), 324–330. https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS &CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med13&AN=27152536.

Martin, P., Hill, A., Ford, M., Barnett, T., Graham, N., & Argus, G. (2022). A Novel Interprofessional Education and Supervision Student Placement Model: Student and Clinical Educator perspectives and experiences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710734

McElfish, P. A., Moore, R., Buron, B., Hudson, J., Long, C. R., Purvis, R. S., Schulz, T. K., Rowland, B., & Warmack, T. S. (2018). Integrating Interprofessional Education and Cultural Competency Training to address Health disparities. Teaching & Learning in Medicine, 30(2), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2017.1365717

Meek, R., Morphet, J., Hood, K., Leech, M., & Sandry, K. (2013). Effect of interprofessional student led beds on emergency department performance indicators. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 25(5), 427–434.

Meuser, T., Cohen Konrad, S., Robnett, R., & Brooks, F. (2022). Telecollaboration in gerontology service learning: Addressing isolation & loneliness in a pandemic. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 43(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2021.1956489

Munn, Z., Pollock, D., Khalil, H., Alexander, L., Mclnerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., Peters, M., & Tricco, A. C. (2022). What are scoping reviews? Providing a formal definition of scoping reviews as a type of evidence synthesis. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 20(4), 950–952.

Ng, E., & Hu, T. (2017). A survey of Canadian interprofessional student-run free clinics. Journal of Interprofessional care, 31(6), 781–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1346590

Ng, K. Y. Y., Leung, G. Y. C., Tey, A. J. Y., Chaung, J. Q., Lee, S. M., Soundararajan, A., Yow, K. S., Ngiam, N. H. W., Lau, T. C., & Wong, S. F. (2020). Bridging the intergenerational gap: The outcomes of a student-initiated, longitudinal, inter-professional, inter-generational home visit program. BMC Medical Education, 20, 1–19.

Ouyang, D., Yuan, N., Sheu, L., Lau, G., Chen, C., & Lai, C. J. (2013). Community Health Education at Student-Run Clinics Leads to sustained improvement in patients’ Hepatitis B Knowledge. Journal of Community Health, 38(3), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-012-9631-3

Palma, M. L., Arthofer, A., Halstead, K. M., Wahba, J. M., & Martinez, D. A. (2020). Service Learning in Health Care for Underserved Communities: University of Iowa Mobile Clinic, 2019. American Journal of Public Health, 110(9), 1304–1307. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305755

Peluso, M. J., Hung, A., Lukasiewicz, A., Chang, H., Ramallo, J., Bartlett, M., Friedland, G., & Ellis, P. (2014). Successful management of latent tuberculosis infection in an Underserved Community by a student-run free clinic. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 25(2), 837–862. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2014.0109

Peters, M. D., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126.

Reumerman, M. O., Richir, M. C., Nieuwenhuis, D., Sultan, P. M., Daelmans, R., Springer, H. E. M., Muller, H., van Agtmael, M., M. A., & Tichelaar, J. (2021). The clinical and educational outcomes of an inter-professional student-led medication review team, a pilot study. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 77(1), 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-020-02972-3

Reumerman, M. O., Richir, M. C., Sultan, R., Daelmans, H. E. M., Springer, H., Grijmans, E., Muller, M., van Agtmael, M. A., & Tichelaar, J. (2022). An inter-professional student-run medication review programme. Reducing adverse drug reactions in a memory outpatient clinic: A controlled clinical trial. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2022.2069748

Rock, J. A., Acuña, J. M., Lozano, J. M., Martinez, I. L., Greer, P. J., Brown, D. R., Brewster, L., & Simpson, J. L. (2014). Impact of an academic-community partnership in medical education on community health: Evaluation of a novel student-based home visitation program. Southern Medical Journal, 107(4), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0000000000000080

Rowe, G. C., Congdon, H. B., Pittman, J., Wiseman, R., & Shields, R. (2021). Interprofessional education clinics and improved outcomes for primary care patients with diabetes. Journal of Interprofessional Education and Practice, 24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2021.100441

Sargison, H., Hill, A. E., Anderson, R., Copley, J., & Booth, J. (2021). Allied health students as service providers in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander early childhood education programs: Perceptions of parents and educators. Australian Journal of Clinical Education, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.53300/001c.25670

Sarovich, E., Lowrie, D., Geia, L., Kris, S., & Cairns, A. (2022). Different meanings… what we want in our lives… a qualitative exploration of the experience of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples in a co-designed community rehabilitation service. Disability & Rehabilitation, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2161645

Schmitt, M. H. P. R. N., Gilbert, J. H. V. C. M. P. F., Brandt, B. F. P., & Weinstein, R. S. M. D (2013). The coming of age for Interprofessional Education and Practice. American Journal of Medicine, 126(4), 284–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.10.015

Schutte, T., Tichelaar, J., Dekker, R. S., van Agtmael, M. A., de Vries, T. P., & Richir, M. C. (2015). Learning in student-run clinics: A systematic review. Medical Education, 49(3), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12625

Sealey, R., George, N., Gordon, S., & Simmons, L. (2017). Dual benefits of a student-assisted interprofessional men’s healthy Lifestyle Pilot Program. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(4), 1133–1141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988315601725

Seymour, C. J., & Cannon, S. (2010). Student-facilitated health promotion intervention for chronic disease self-management in at-risk elders: Reflections from the field. Journal of Allied Health, 39(2), 120–128.

Shekar, A., Gross, A., Luebbers, E., & Honsky, J. (2020). Effects of an Interprofessional Student-Led Sexual Education Program on Self-Efficacy and attitudes about sexual violence in youths in Juvenile Detention. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 33(3), 302–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2019.12.005

Sheu, L. C., Toy, B. C., Kwahk, E., Yu, A., Adler, J., & Lai, C. J. (2010). A model for Interprofessional Health Disparities Education: Student-Led Curriculum on Chronic Hepatitis B infection. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25, S140–S145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1234-z

Sick, B., Sheldon, L., Ajer, K., Wang, Q., & Zhang, L. (2014). The student-run free clinic: An ideal site to teach interprofessional education? Journal of Interprofessional care, 28(5), 413–418. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.907779. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/

Sick, B., Zhang, L., & Weber-Main, A. M. (2017). Changes in Health Professional Students’ attitudes toward the Underserved: Impact of extended participation in an Interprofessional Student-Run Free Clinic. Journal of Allied Health, 46(4), 213–219. https://ovidsp.ovid.com.ez.library.latrobe.edu.au/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS &CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed18&AN=623375435.

Simpson, S. A., & Long, J. A. (2007). Medical student-run health clinics: Important contributors to patient care and medical education. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(3), 352–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0073-4

Spencer, J., Woodroffe, J., Cross, M., & Allen, P. (2015). A golden opportunity: Exploring interprofessional learning and practice in rural clinical settings. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29(4), 389–391. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.970250

Stanley, M. (2014). Qualitative descriptive: A very good place to start. Qualitative research methodologies for occupational science and therapy (pp. 21–36). Routledge.

Stephens, D., Ramedani, S., Tupinio, M., Lambert, K., & Artrip, R. (2020). Using time limits to improve patient visits & clinic flow at a student-run free clinic. Journal of Student-Run Clinics, 6(1).

Stetten, N. E., Black, E. W., Edwards, M., Schaefer, N., & Blue, A. V. (2019). Interprofessional service learning experiences among health professional students: A systematic search and review of learning outcomes. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 15, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2019.02.002

Stuhlmiller, C. M., & Tolchard, B. (2015). Developing a student-led health and wellbeing clinic in an underserved community: Collaborative learning, health outcomes and cost savings. BMC Nurs, 14, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-015-0083-9

Stuhlmiller, C. M., & Tolchard, B. (2018). Population Health outcomes of a student-led Free Health Clinic for an Underserved Population: A naturalistic study. Journal of Community Health, 43(1), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-017-0402-z

Suen, J., Attrill, S., Thomas, J. M., Smale, M., Delaney, C. L., & Miller, M. D. (2020). Effect of student-led health interventions on patient outcomes for those with cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular disease risk factors: A systematic review. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 20(1), 332. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01602-1

Sultan, R., van den Beukel, T. O., Reumerman, M. O., Daelmans, H. E. M., Springer, H., Grijmans, E., Muller, M., Richir, M. C., van Agtmael, M. A., & Tichelaar, J. (2022). An Interprofessional Student-Run Medication Review Program: The clinical STOPP/START-Based outcomes of a controlled clinical trial in a geriatric outpatient clinic. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 111(4), 931–938. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.2475

Timm, J. R., & Schnepper, L. L. (2021). A mixed-methods evaluation of an interprofessional clinical education model serving students, faculty, and the community. Journal of Interprofessional care, 35(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1710117

Tokolahi, E., Broman, P., Longhurst, G., Pearce, A., Cook, C., Andersen, P., & Brownie, S. (2021). Student-led clinics in Aotearoa New Zealand: A scoping review with Stakeholder Consultation. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 14, 2053–2066. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S308032

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

van Diggele, C., Roberts, C., Burgess, A., & Mellis, C. (2020). Interprofessional education: Tips for design and implementation. BMC Medical Education, 20(2), 455. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02286-z

VanKuiken, D. M., Schaefer, J. K., Hall, F., M., & Browne, F. R. (2016). Integrating interprofessional education into the curriculum: Challenges and solutions for a university without a medical center. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 2, 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2015.12.002

Virtue, S. M., Rotz, M. E., Boyd, M., Lykon, J. L., Waldron, E. M., & Theodorou, J. (2018). Impact of a novel interprofessional dental and pharmacy student tobacco cessation education programme on dental patient outcomes. Journal of Interprofessional care, 32(1), 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1378171

Walker, C., Forbes, R., Osborn, D., Lewis, P. A., Cottrell, N., Peek, S., & Argus, G. (2022). The transformation of a student-led health clinic in rural Australia from a face-to-face service to a telehealth model: Evaluation of student and client experiences during a COVID-19 driven transition. Focus on Health Professional Education-a Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(2), 79–92.

White, M. S., Burns, C., & Conlon, H. A. (2018). The impact of an Aging Population in the Workplace. Workplace Health Saf, 66(10), 493–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079917752191

Wilson, O. W. A., Broman, P., Tokolahi, E., Andersen, P., & Brownie, S. (2023). Learning outcomes from participation in Student-Run Health clinics: A systematic review. J Multidiscip Health, 16, 143–157. https://doi.org/10.2147/jmdh.S385709

World Health Organization (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework-for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative-practice

Wynne, D., & Cooper, K. (2021). Student-led rehabilitation groups and clinics in entry-level health education: A scoping review. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 19(11), 2958–2992. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00340

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Mrs Elizabeth Lawrence and Mrs Annette Messell for their library support, and Ms Claire Thwaites for her assistance with the quality appraisal.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P.V, M.E.M, M.S and L.C. conceptualised the study and analysed the data. J.P.V extracted data and wrote the initial article draft. M.E.M, M.S and L.C reviewed and edited the draft. All authors reviewed and finalised the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declarations

This scoping review was registered in Open Science Framework, registration number osf.io/5vbdz.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions