Abstract

Aim

Socioeconomic marginalization and inequalities in well-being and health in adults have been shown to be rooted in the early childhood experience. In particular, childhood poverty and parental income may influence children’s well-being in multiple and diverse ways, as it is known that parental poverty impedes cognitive function.

Subjects and methods

The 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort includes a complete census of children born in a single year. The children were followed up from birth until end of 2012 using official registers maintained by the Finnish authorities. Cohort members who survived till the end of follow-up were included in the study (N = 58,818). Path modelling was used to analyze relations of theoretical constructs; parental adaption (PA), parental psychiatric involvement (PPI), family socioeconomic status (SES) as mediator, and child life outcomes (CLO) as outcome. Three models were made; a full model, a mediational model (where PA and PPI only have a direct effect on CLO through SES), and a non-mediational model with only direct effects of PA and PPI on CLO. A multiple group analysis was undertaken by cohort members’ different educational outcomes.

Results

The best-fitting model suggested that as parental psychiatric involvement increases and parental adaptation failures increase, the socio-economic status of the family is compromised; in turn, poverty predicts increased adverse life outcomes for children. The restricted mediational model fits best on the data, and equally well for all educational outcomes. Childhood poverty remains the most significant determinant of early adult outcomes, regardless of school performance.

Conclusion

More policy effort needs to be enacted to reduce childhood poverty and its consequences in Finland.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marginalization can be defined as a cumulative process of social exclusion leading to an entrenched position at the lowest margins of society. Outcomes such as early school leaving, long-term unemployment, and dependence on means-tested welfare services are examples of relevant stages in this process. The integration of individuals into the society begins at birth, and the foundation for well-being is built in childhood. Socio-economic marginalization and inequalities in well-being and health in adults have been shown to be rooted in early childhood experience (Ekblad et al. 2010; Fryers and Brugha 2013; Lahti et al. 2010; Patterson 2007; Räikkönen et al. 2011; Veijola et al. 2008; Weaver 2009). These results suggest that childhood poverty and parental income may influence children’s well-being in multiple and diverse ways. Other research has shown that risk factors for health and welfare problems stem from the pre- and perinatal period, and they include genetic as well as environmental influences (Robinsson et al. 2008; Thompson et al. 2010). Pre- and perinatal factors have been shown to affect childhood and adolescent outcomes such as mortality and morbidity (Xu et al. 1999a; Xu et al. 1999b), behavioral problems (Kelly et al. 2001; Kotimaa et al. 2003; Linnet et al. 2003), delinquent and criminal behavior (Arseneault et al. 2000; Raine et al. 1997; Yliherva et al. 2001), cognitive and motor functioning (Jefferis et al. 2002), and teenage pregnancy (Christoffersen 2003). It is, however, less clear to what extent these effects are sustained through adulthood, and what is the independent role of each of the risk factors. What is evident is that marginalization and inequalities in health, income, and other opportunities in life chances are often interwoven (Ristikari et al. 2016).

Previous longitudinal cohort studies, including the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort study, have shown that problems in education, mental health, criminality, and ability to live an economically independent life accumulate in early adulthood. Problems in wellbeing, such as NEET (Not in employment, education, or training) status, mental health, criminality, and dependence on social assistance recipiency tend to cluster particularly for those persons with only compulsory education (Larja et al. 2016; Paananen et al. 2012; Ristikari et al. 2016). Risk factors for the accumulation of wellbeing problems in early adulthood have been shown to be parental low socioeconomic status and low education, financial hardship, divorce or death, problems in health, and mental health (Paananen et al. 2012; Ristikari et al. 2016).

Theoretical foundation and aims of the study

In social epidemiology, the link between human development and health is best understood by a life-course framework, which is conceptualised as the study of long-term effects of physical and social exposures during gestation, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, and later adult life (Ben-Shlomo and Kuh 2002; Kuh et al. 2003). In this approach, the ‘critical period model’ postulates that for example, in-utero exposures have long-lasting effects on later health which are not modified in any dramatic way by later exposures. The ‘accumulation of risk model’, in turn, recognizes later life exposures as important effect modifiers, acting in an additive way either by forming ‘chains of risk’, or becoming ‘triggers’, the final link in the chain leading to disease. ‘Sensitive periods’ are those phases of life during which an exposure has a stronger effect than it would have at other times.

However, as the environmental exposures operate at different levels, these can be well described through systemic theories, such as Bronfenbenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1994) which highlights the importance of studying human development in the context of multiple environments, also known as ecological systems. The ecological systems range from the most intimate home ecological system (‘microsystem’) to the larger school/community system (‘mesosystem’) and the most expansive system (‘macrosystem’), which is society and culture. The ‘chronosystem’ includes a dimension of time, which may be related to, for example, change in family structure, living environment, and parent’s employment status, in addition to immense society changes such as economic cycles.

The current study aims at dissecting the role of parental mental health, education, and socioeconomic factors on the life outcomes of their off-spring in early adulthood. Specifically, we use a path-modeling approach to study the direct and mediated effect of parental risk factors on their off-spring outcomes as operationalized by a combined measure of psychiatric out/inpatient care and social assistance receipt. We study the role of parental risk factors on the off-spring outcomes using a multi-group approach, based on school performance.

The uniquely extensive data set of the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort that we utilize in our analysis allows us to dig into the ecological environment (Bronfenbrenner 1994) in which children develop, thus allowing us to reveal new and important findings about child life outcomes. By combining a large number of indicators of intergenerational wellbeing and health in a path analysis, we are able to show not only the way in which childhood conditions impact later wellbeing but also to show the path through which the process of marginalization is most exacerbated.

Material and methods

The 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort (1987 FBC) is a longitudinal nationwide follow-up data study including a complete census of all infants born in a single year who have subsequently been followed over time until age 25, with detailed forms of documentation of their own and their parents’ health status and social circumstances from the perinatal period into early adulthood. The data were gathered from Finnish national registers, which are shown to be of high quality and appropriate for research purposes (Paananen and Gissler 2011).

The children surviving the perinatal period were included in the study (N = 59,476). During the study period, 658 (1.1%) participants had died by 31 December 2012. These cohort members were included in the study until death. At the end of the follow-up, 58,818 cohort members (98.9%) were still alive and living in Finland.

General conceptual considerations

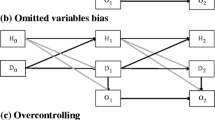

We began this research by considering the two processes by which parental variables impact the life outcomes of children. The child life outcome model is presented in Fig. 1. The model has two exogenous variables; they are parental psychiatric involvement (PPI) and parental adaptation (PA). Each of these constructs is the sum of binary variables as described below. A mediating variable is the socioeconomic status (SES) of the family; this construct was formed by summing the binary variables ‘parents’ social assistance’ and ‘cumulative duration of social assistance’. The model also contains one endogenous construct termed children’s life outcomes (CLO) which was formed by summing the binary variables regarding cohort member’s mental health problems and receiving social assistance. Disturbances were also specified for the family SES and CLO constructs, although they are not presented in Fig. 1. The full model specified in Fig. 1 assumes that parental psychiatric involvement (PPI) and parental adaptation (PA) may be correlated, and the curved line with two arrow heads represents this assumption.

Variable descriptions

The theoretical construct “parental adaptation” (PA) is a sum of binary variables ‘mother less than 20 years’, ‘mother’s education’ and ‘father’s education’ (0/1/2/3). Data on a cohort member’s mother’s age (classified in the analyses as under 20 years vs 20 yrs or more at birth) was obtained from the Medical Birth Register (MBR). The variable “mother less than 20 years” was coded as a binary variable, yes = 1/no = 0. We considered the educational level of both parents separately, and the data on the highest educational level of cohort members’ mother/father during the time the cohort member was aged under 16 years was received from Statistics Finland and classified as binary variable “only primary school” (up to 9 years) = 1, “higher than primary education” (10 years or more) = 0.

The theoretical construct “parental psychiatric involvement” (PPI) is a sum of binary variables ‘mother’s psychiatric in/outpatient care’, ‘father’s psychiatric in/outpatient care’, ‘mother’s psychiatric disability pension’ and ‘father’s psychiatric disability pension’ (0/1/2/3/4). The Finnish Hospital Discharge Register (HDR), maintained by the National Institute for Health and Welfare, includes all inpatient care episodes from all Finnish hospitals since 1969 and all specialized-level outpatient visits in public hospitals since 1998. Data on parental psychiatric care were collected from the HDR, for psychiatric inpatient care between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2008. The variables “mother’s psychiatric in/outpatient care” and “father’s psychiatric in/outpatient care” were coded as binary variables, yes = 1/ no = 0, based on whether one or the other parent had been treated in either inpatient or outpatient psychiatric care during the time the cohort member was aged under 16 years. Persons with an illness or disability that precludes them from earning a reasonable living while aged 16–64 years are entitled to a disability pension payment. Information on parental psychiatric disability pension was received from the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, while the psychiatric disability pension (yes = 1/no = 0) indicated whether the mother or father of a cohort member had been granted disability pension based on psychiatric diagnoses during the time the cohort member was aged under 16 years.

The theoretical construct “family socioeconomic status” (SES) is a sum of binary variables “parents’ social assistance” and “cumulative duration of social assistance” (0/1/2). Recipients of social assistance are registered by the National Institute for Health and Welfare. Social assistance provided by social services to a household from municipal funds when other sources of income are insufficient to ensure that the basic needs of a person or a family are met. Parental social assistance was used as an indicator of family financial hardship, and was classified in the analysis as binary, yes = 1/no = 0. Parental social assistance was registered for the biological mother, biological father, or both parents during the time when the cohort member was under 16 years of age. The cumulative duration of social assistance was registered for the mother, father, or both, and was calculated as a sum of all periods of receiving social assistance during the time when the cohort member was aged under 16 years and was classified as binary variable “no social assistance or less than 5 years” = 0 vs “5 years or more social assistance” = 1.

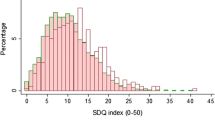

The theoretical construct “children’s life outcomes” (CLO) (0/1/2) is a sum of binary variables “cohort member’s psychiatric in/outpatient care” and “cohort member’s social assistance”. Data on the cohort member’s psychiatric diagnoses were collected from specialized care (inpatient or outpatient care) and reported using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 in 1987 and 1995 (290–319) and ICD-10 since 1996 (F00–99). It was classified as a binary variable yes = 1/no = 0 based on whether the cohort member had been treated in either inpatient or outpatient psychiatric care or not during 1987–2012. Cohort member’s receipt of social assistance was used as an indicator of their poor financial situation (classified in analyses yes = 1/no = 0). Cohort member’s social assistance was registered during 2002–2012.

“School” (0 = good/1 = medium/2 = poorest) is a sum of binary variables ‘early school-leaver’ (yes = 1, no = 0) and ‘grade point average (GPA)’ (4–6 = 1, 7–10 = 0). Information on the highest educational level of a cohort member was received from Statistics Finland; depending on whether the cohort member had completed secondary level education or not, the educational level was classified as binary variable; ‘early school leaver’: yes = 1/no = 0. The information on cohort member’s GPA on the last year of primary level education (from 1st to 9th school year) was received from Finnish National Board of Education. The first known GPA was taken into account during 2003–2012 (from spring 2003 to fall 2012) and was classified as GPA 4–6 = 1/GPA 7–10 = 0.

Statistical methods — hypothesized process mechanisms: full and restricted models

To analyze relations of theoretical constructs, path modelling was used. As specified, the full model acknowledges that CLOs are affected both directly and by a mediational mechanism. That is, there are direct effects of PPI and PA on CLO (parameters b and c respectively in Fig. 1). In addition, the model also specifies a mediational process in which PPI and PA directly affect the family SES (parameters d and e respectively), and that SES affects CLO (parameter f). The restricted non-mediational model assumes that PPI and PA have a direct effect on CLO, and that SES does not mediate the effects of PPI and PA on CLO. Under these assumptions, parameters d, e, and f of Fig. 1 are constrained to zero. The restricted mediational model assumes that the effects of PPI and PA on CLO are mediated by family SES. Under these assumptions, parameters b and c are constrained to zero and only the mediational paths are estimated (i.e., parameters d, e, and f).

These different models were estimated and, when available, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was used to determine which specification best fitted the data. First, a full model was estimated in which all the parameters of the model in Fig. 1 were estimated. Then, constraints were imposed to estimate direct effects of PPI and PA on CLO unmediated by SES (i.e., the restricted non-mediational model). Lastly, a mediational model was specified in which the effects of PPI and PA were fully mediated by SES (i.e., the restricted mediational model). The parameter estimates were computed using AMOS 23.

Results

Descriptive statistics of constructs are presented in Table 1. The full model as specified in Fig. 1 is just-identified. This means that given the number of measured constructs, there are sufficient degrees of freedom to estimate all the parameters of the model. As there are no residual degrees of freedom for the model, the chi square measure of model fit will be zero and does not provide an assessment of the adequacy of the model. In addition, the RMSEA was not available. All parameter estimates for the full model were reliably different from zero and are summarized in Table 2. Squared multiple correlations were 0.144 and 0.147 for the SES and CLO constructs respectively. Approximately 14% of the variance in family SES and about 15% of the variance in CLO was explained by the full model. This full model was used as a baseline against which to compare alternative specifications. The RMSEA for the independence model that assumes the values of all parameters are 0 is equal to 0.179 with 90% confidence interval of 0.177 to 0.181 with p value less than 0.001. This showed that the null model did not adequately fit the data.

In the first re-specified model, restricted non-mediational model, the effects of PPI and PA on SES were fixed to zero (parameters d and e respectively) and the effect of SES on CLO (parameter f) was also fixed to zero. Only the direct effects of PPI and PA on CLO (parameters b and c) were estimated. This model specification produced a χ2(3) = 15.82. All parameter estimates were reliably different from zero and are summarized in Table 2. The RMSEA was equal to 0.299 with 90% confidence intervals of 0.296 to 0.303, with the probability of close fit equal to 0. These results showed that the model with only the direct effects of PPI and PA on CLO did not adequately fit the data. The squared multiple correlation for the CLO construct was 0.043, and showed that the direct effects of PPI and PA explained about 4% of the variance in CLO. The results showed that the non-mediational model did not adequately fit the data and was theoretically inadequate.

Both the full model and the restricted non-mediational model produced parameter estimates that were reliably different from zero; the fit of the full model was indeterminate, whereas the fit of the direct effect model was unacceptable. The model was then re-specified by fixing the direct effects of PPI and PA on CLO to zero while estimating parameters d, e, and f of the restricted mediational model. Results of this analysis showed that all parameter estimates were reliably different from zero; they are summarized in Table 2. The RMSEA was equal to 0.054 with a 90% confidence interval of 0.049 to 0.059, with the probability of close fit equal to 0.101. The χ2(2) equaled 340.55, with p < 0.001. The squared multiple correlations for the SES and CLO constructs were 0.144 and 0.142 respectively, and showed that about 14% of the variance in each of these constructs was explained by the model. Overall, the fit of the mediational model was inadequate, as evidenced by the magnitude of the RMSEA and the measures of close fit equal to 0.101.

Multiple group models

We then considered if the full model and the restricted mediational model would fit the data for children with different educational outcomes. Previous research has suggested that educational attainment is perhaps the most significant protective factor for later life outcomes in conditions of childhood adversity (Feinstein et al. 2006). To accomplish this, a multiple groups analysis was undertaken. We found that 41,750 children had good educational outcomes (school group 1), 11,056 had medium educational outcomes (school group 2) and 3826 children had poor educational outcomes (school group 2).

We began by estimating the full model, referred to as the configural model in multiple groups analysis (Byrne 2010), with no constraints across the different educational outcome groups. Consequently, parameter estimates in the configural model were free to vary for each group. The model was just-identified, and therefore the chi-square is equal to zero and is not interpretable. Squared multiple correlations were available for the SES and CLO constructs for each educational group. The results of these analyses are summarized in Table 3.

Among those with good educational outcomes (n = 41,750), all parameter estimates of the model in Fig. 1 were statistically reliable. Approximately 11% and 9% of the variance in SES and CLO were explained by the specified model. Considering the hypothesized causal parameters (i.e., d and e through f), the direct effects of PPI and PA on CLO (i.e., b and c respectively) showed the weakest effects compared to those in the mediational portion of the model (i.e., d, e, and f).

Among those with medium educational outcomes (n = 11,056), five of six parameter estimates of the model in Fig. 1 were statistically reliable. The effect of PA on CLO was not reliable statistically. Approximately 12% and 11% of the variance in SES and CLO respectively were explained by the model. Considering the hypothesized causal parameters (i.e., d and e through f), the direct effects of PPI and PA on CLO (i.e., b and c respectively) showed the weakest effects compared to those in the mediational portion of the model (i.e., d, e and f).

Among those with the poorest educational outcomes (n = 3826), five of six parameter estimates of the model in Fig. 1 were statistically reliable. As seen for children with medium outcomes, the effect of PA on CLO was not reliable statistically among those with the poorest outcomes. Approximately 16% and 10% of the variance in SES and CLO, respectively were explained by the specified model. Considering the hypothesized causal parameters (i.e., d and e through f), the direct effects of PPI and PA on CLO (i.e., b and c respectively) showed the weakest effects compared to those in the mediational portion of the model (i.e., d, e, and f).

These results, summarized in Table 3, suggested that constraining the direct effects of PPI and PA on CLO to zero would yield a more parsimonious mediational model. Therefore, a multiple groups analysis (good, medium, and poor educational outcomes) was conducted with the direct effects (i.e., parameters b and c) constrained to zero. We also considered model fit with structural weights constrained and unconstrained across groups.

Multiple groups analysis: restricted model with constrained and unconstrained structural weights

The parameters of restricted model were estimated with the direct effects of PPI and PA on CLO fixed to zero among children with good (n = 41,750), medium (n = 11,056) and the poorest (n = 3826) educational outcomes. The structural weights were constrained to be equal across the three educational outcome groups. Across the three groups (n = 56,632) all parameter estimates of the restricted mediational model were statistically reliable. The estimates that were constrained to be equal across educational outcome groups are presented in Table 4. The unstandardized weights quantifying the effect of PPI and PA on CLO needs to be SES were 0.327 (p = 0.006) and 0.232 (p = 0.004) respectively. The unstandardized weight quantifying the effect of SES on CLO was 0.297 (p = 0.004). The RMSEA for the model with structural weight constrained to equality across groups was 0.018 with 90% confidence interval of 0.016 to 0.020, with p close = 1.00, and χ2(12) = 236.44, p > 0.01. For the educational outcome groups, approximately 9–11% of variance in CLO was explained by the mediational models with structural weights constrained to equality across groups. Also, approximately 9–12% of the variance in SES was explained by the mediational model with structural weights constrained to equality across groups.

When the structural weights of the model were unconstrained across groups, the RMSEA was 0.024 with a 90% confidence interval of 0.021 to 0.027, with p close = 1.00. The unconstrained model had χ2(6) = 202.72. Difference between models where structural weights were constrained and unconstrained was 33.72 (6). It is noteworthy that the confidence intervals for the RMSEA of the constrained and unconstrained models do not overlap; consequently, the model with structural weights constrained to equality across the educational outcome is judged to best fit the data.

Best-fitting model

Based on the estimates produced and the measures of model fit, the mediational model seen in Fig. 2 was judged to best fit the data. All parameter estimates were reliably different from zero. The RMSEA indicated the mediational model with parameter estimates constrained to equality across educational outcome groups fitted best relative to the unconstrained structural estimates. This model suggested that as parental psychiatric involvement increases and parental adaptation failures increase, the socio-economic status of the family is compromised; in turn, poverty predicts increased adverse life outcomes for children.

Discussion

This study pitted two competing conceptual models of the determinants of children’s life outcomes (CLO) to an empirical test. The direct effect model assumed that family socio-economic status does not mediate the effects of parental psychiatric involvement (PPI) and parental involvement (PA) on the life outcomes of a child. Presumably, the vast safety net available in a country like Finland, with readily available social welfare support, would buttress the impact of social class on the life outcomes of children. Alternatively, the mediational model assumed that in spite of the safety net, family socioeconomic status does indeed impact the outcomes in children’s lives. The results of this research show that the mediational model fits the data much better than the direct effect model.

As such, the conclusion that the welfare state can mitigate the effects of family poverty on children’s life outcomes is seemingly false. In other words, simply being in and part of a strong welfare state with universal provision of services and comparatively high benefits compared to other countries does not result in the life chances of the children of poor families increasing relative to the rest of the population. The ecological environment is far more complex than this. The findings of this research suggest therefore that interventions to improve the lives of children should be targeted at mitigating the adverse impact of parental psychiatric involvement and impediments to parental adaptation. This because they both have a direct impact on the financial situation of the family, which in turn is the most important proximate determinant of the life outcomes of children.

Our study operationalized family poverty with a measure of social assistance receipt. In Finland, municipalities provide social assistance as a last-resort benefit for individuals when other forms of income are not enough to guarantee that basic needs of an individual or a family are met. The Nordic welfare state model assumes fairly generous family and other benefits, with the idea that the last resort means-tested safety net would only rarely be needed. This characteristic of the Nordic model was, however, not fully functional in the 1990s when the 1987 Finnish birth cohort grew up, and when a large section of the society was struggling financially as a result of the major Europe-wide recession. Approximately 38% of the cohort member’s parents had to resort to social assistance for some time as a result of widespread unemployment. In order to capture the more serious financial difficulties, our study included in the construct “Family SES” as a measure of an extended period of social assistance receipt. The results of our study therefore indicate that in the context of a Nordic welfare state, at a time of widespread unemployment and failure of the family, together with other benefits to support a basic living standard, particularly for an extended period, the life outcomes of children become jeopardized.

The results of the study also lead us to question the ability of the Finnish educational system to weaken the impact of adverse childhood conditions on later life outcomes. Our analysis showed that low parental income is the most proximate cause of poor later life outcomes, and that the impact was most significant for persons with the poorest educational outcomes. The much acclaimed Finnish school system (Sahlberg 2011) noted for producing excellent educational outcomes, seems, in light of the results of our study, not fully capable of removing the impact of adverse childhood conditions on life outcomes. Previous research has shown that the Finnish school system after its last major reform has been successful in improving the cognitive skills of the students whose parents have only basic education (Pekkarinen et al. 2009); but when looking further into the life course, namely at the early adult outcomes, it appears that childhood poverty remains the most significant hindrance to the fulfilment of one’s capabilities regardless of educational outcomes.

References

Arseneault L, Tremblay RE, Boulerice B, Saucier JF (2000) Minor physical anomalies and family adversity as risk factors for violent delinquency in adolescence. Am J Psychiatry 157:917–923. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.917

Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D (2002) A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epiodemiol 31:285–293

Bronfenbenner U (1994) Ecological models of human development. International encyclopedia of education, 2nd edn. Elsevier, Oxford

Byrne BM (2010) Structural equation modeling with AMOS, 2nd edn. Routledge, New York

Christoffersen M (2003) Motherhood and induced abortion among teenagers: a longitudinal study of all 15–19 year old Danish women born in 1966. Children. Youth and Families Working Paper 2 Copenhagen (Denmark): Danish National Institute of Social Research

Ekblad M, Gissler M, Lehtonen L, Korkeila J (2010) Prenatal smoking exposure and the risk of psychiatric morbidity into young adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67:841–849. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.92

Feinstein L, Sabates R, Anderson TM, Sorhaindo A, Hammond C (2006) 4. What are the effects of education on health?. In Measuring the effects of education on health and civic engagement: Proceedings of the Copenhagen Symposium of the OECD

Fryers T, Brugha T (2013) Childhood determinants of adult psychiatric disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 9:1–50. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901309010001

Jefferis BJ, Power C, Hertzman C (2002) Birth weight, childhood socioeconomic environment, and cognitive development in the 1958 British birth cohort study. BMJ 325:305

Kelly YJ, Nazroo JY, McMunn A, Boreham R, Marmot M (2001) Birthweight and behavioural problems in children: a modifiable effect? Int J Epidemiol 30:88–94

Kotimaa AJ, Moilanen I, Taanila A, Ebeling H, Smalley SL, McGough JJ, Hartikainen AL, Järvelin M-R (2003) Maternal smoking and hyperactivity in 8-year-old children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42:826–833. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CHI.0000046866.56865.A2

Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, Power C (2003) Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health 57:778–783. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.10.778

Lahti M, Räikkönen K, Wahlbeck K, Heinonen K, Forsén T, Kajantie E, Pesonen AK, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Eriksson JG (2010) Prenatal origins of hospitalization for personality disorders: the Helsinki birth cohort study. Psychiatry Res 179:226–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.08.024

Larja L, Törmäkangas L, Merikukka M, Ristikari T, Gissler M, Paananen R (2016) NEET-indikaattori kuvaa nuorten syrjäytymistä (in Finnish) [the NEET-indicator reflects social exclusion of young]. Tieto Trendit 2:20–27

Linnet KM, Dalsgaard S, Obel C, Wisborg K, Henriksen TB, Rodriguez A, Kotimaa A, Moilanen I, Thomsen PH, Olsen J, Järvelin M-R (2003) Maternal lifestyle factors in pregnancy risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated behaviors: review of the current evidence. Am J Psychiatry 160:1028–1040. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1028

Paananen R, Gissler M (2011) Cohort profile: the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort. Int J Epidemiol 41:641–945. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr035

Paananen R, Ristikari T, Merikukka M, Rämö A, Gissler M (2012) Children’s and youth’s well-being in light of the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort study. Report 52. National Insitute for Health and Welfare (THL), Helsinki. 46 pp

Patterson PH (2007) Maternal effect on schizophrenia risk. Science 318:576–577. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1150196

Pekkarinen T, Uusitalo R, Kerr S (2009) School tracking and intergenerational income mobility: evidence from the Finnish comprehensive school reform. J Public Econ 93:965–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.04.006

Räikkönen K, Lahti M, Heinonen K, Pesonen AK, Wahlbeck K, Kajantie E, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Eriksson JG (2011) Risk of severe mental disorders in adults separated temporarily from their parents in childhood: the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. J Psychiatr Res 45:332–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.07.003

Raine A, Brennan P, Mednick SA (1997) Interaction between birth complications and early maternal rejection in predisposing individuals to adult violence: specificity to serious, early-onset violence. Am J Psychiatry 154:1265–1271. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.154.9.1265

Ristikari T, Törmäkangas L, Lappi A, Haapakorva P, Kiilakoski T, Merikukka M, Hautakoski A, Pekkarinen E, Gissler M (2016) Suomi nuorten kasvuympäristönä. 25 vuoden seuranta vuonna 1987 Suomessa syntyneistä nuorista aikuisista (in Finnish) [Finland as a growth environment for young people. 25-year follow up of those born in Finland 1987]. Report 9. National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), Helsinki

Robinsson M, Oddy WH, Li J, Kendall GE, de Klerk NH, Silburn SR, Newnham JP, Stanley FJ, Mattes E (2008) Pre- and postnatal influences on preschool mental heatlh: a large-scale cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49:1118–1128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01955.x

Sahlberg P (2011) Finnish lessons. What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? Teachers College Press, New York

Thompson L, Kemp J, Wilson P, Pritchett R, Minnis H, Toms-Whittle L, Puckering C, Law J, Gillberg C (2010) What have birth cohort studies asked genetic, pre- and perinatal exposures and child and adolescent onset mental health outsomes? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 19:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-009-0045-4

Veijola J, Läärä E, Joukamaa M, Isohanni M, Hakko H, Haapea M, Pirkola S, Mäki P (2008) Temporary parental separation at birth and substance use disorder in adulthood. A long-term follow-up of the Finnish Christmas Seal Home Children. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 43:11–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0268-y

Weaver IC (2009) Shaping adult phenotypes through early life environments. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 87:314–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdrc.20164

Xu B, Järvelin M-R, Pekkanen J (1999a) Prenatal factors and occurrence of rhinitis and eczema among offspring. Allergy 54:829–836. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00117.x

Xu B, Pekkanen J, Järvelin M-R, Olsen P, Hartikainen AL (1999b) Maternal infections in pregnancy and the development of asthma among offspring. Int J Epidemiol 28:723–727. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/28.4.723

Yliherva A, Olsen P, Mäki-Torkko E, Koiranen M, Järvelin M-R (2001) Linguistic and motor abilities of low-birthweight children as assessed by parents and teachers at 8 years of age. Acta Paediatr 90:1440–1449

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL). This research was supported in part by RI-INBRE Grant, to the last author, #2P20GM103430 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors, and do not represent the official views of NCRR, NIGMS, or NIH. Academy of Finland grants 308556 (PSYCOHORTS) and 288960 (Time trends in child and youth mental health, service use and wellbeing in different Finnish cohorts) supported the work of Dr. Ristikari and MSc. Merikukka.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study obtained ethics approval of the National Institute for Health and Welfare (Ethical committee §28/2009), and permission to use the register data was obtained from all register keeping organizations.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ristikari, T., Merikukka, M., Savinetti, N.F. et al. Path modeling of children’s life outcomes: the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort. J Public Health (Berl.) 27, 761–769 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-018-0997-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-018-0997-2