Abstract

Natural hazard catalogs provide information on past documented events, often as the most reliable indication to ensure future hazard mitigation performance—influencing both social and economic welfare. For such reasons, knowledge about the completeness is important and allows to define the period for which the historical range of variability of the documented events can be stated. Based on an extensive collection of torrential events in Austria (more than 21,000), a robust completeness analyses is presented, based on historiographic as well as statistical approaches. The analyses are based on a 3 W-standard, “When did it happen?”, “What happened?”, and “Where did it happen?”, for all documented events. Hence, a completeness of the whole torrential event catalog can be assumed, if the yearly number of events is independent of the reporting rate—the number of reported events per year. We further present completeness periods of (i) the documented torrential processes, “floods”, “bedload processes”, and “debris flows” as well as of (ii) the documented event-intensities, “low”, “medium”, “high”, and “extreme”. In a first order analysis, an increase in events for the resulting completion period could not be detected. However, a strong correlation to the total rainfall sum above the 99th percentile seems to be evident.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Alpine regions, human settlements, infrastructures and environmental resources are frequently endangered by flood or bedload transport processes (flood events with high sediment transport rates) and mass movements like debris floods or debris flows. Such torrential processes differ in their formation, procedure as well as dynamic behavior, and thus they are all related to occur in steep headwater catchments often associated with a high density of population. In countries like Austria, people always meet a challenge to find an accurate balance between the imminence of natural hazards and the progress in spatial developments. For this reason, awareness of natural hazards is high, and reports of catastrophic events related to these kind of processes can bedated back to the early middle ages. In Austria, studies about hazard assessment procedures for torrential processes started at the end of the 19th century (Duile 1826; Müller 1857; Landolt 1886; Stiny 1907, 1909), and since then there has been a shift from heuristic hazard reduction strategies to a quantified risk culture. Today, risk culture has many facets in dealing with natural hazards, and risk reduction has become socially relevant (Thaler et al. 2019; Keiler and Fuchs 2016). This is reasoned by a society’s awareness—also on the political level—that a complete protection against natural hazards is not affordable and economically justifiable (Wilhelm 1996; Fuchs and McAlpin 2005; Fuchs et al. 2008), and that the global financial and insurance markets, upon which the global economy depends, are essentially risk-driven Smith and Petley 2009. However, the reliability of modern risk reduction strategies for natural hazardous processes depends on messages from the past, either from event documentations, stratigraphic analysis, or analysis of geomorphological field traces.

In Austria, stratigraphic and detailed geomorphologic analysis are resource and cost intensive and thus provide only selective information of past torrential events (Mayer et al. 2010; Procter et al. 2011; Schraml et al. 2013). For these reasons, more attention was paid to existing event reports. From the early middle ages (544) to present (2017), a total of 21,429 torrential events have been collected and stored in the Austrian event catalog, hosted by the Forest Technical Service of Avalanche and Torrent control, Austria WLK digital event catalog 2018. However, in Austria, a systematic collection of torrential event information was motivated by the introduction of the “flood reports” in the 1970s. The flood reports were a consequence to the paradigm-shifting introduction of the hazard zone mapping and have found their legally foundation in the Austrian Forest Act 1975, and an associated decree Regulation: Hazard Zone Maps 1976. It states that a collection of reasonable information about the frequency and extent of previous damage due to torrents or avalanche must be created, which resulted in event histories, compiled for the watersheds under study. These fragmented, watershed specific event catalogs were collected, digitized, harmonized, and integrated, together with historical and archival information (before 1970), into one central Austrian torrential event catalog during the years 2008 to 2010 (Hübl et al. 2008a-1; Hübl et al. 2009).

Thus, optimistically the last 40 years have been grounded in systematically observed and collected data, and it seems therefore indispensable to discuss some of the possible inherent biases of one of the most extensive collections of torrential events worldwide, which can also be considered as a rich source of information on torrential events in the Eastern European Alps.

In this study, we present the robust completeness analyses of the Austrian torrential event catalog considering both, historiographic as well as statistical approaches. The objective is to find the year from which on the torrential catalog can be assumed complete. The analyses are based on the 3 W-Standard, “When did it happen?”, “What happened?”, and “Where did it happen?”, for all documented events. Beside the completeness period for the whole Austrian torrential event catalog, we further present completeness periods of (i) the documented torrential processes, “floods”, “bedload processes”, and “debris flows” as well as of (ii) the documented event intensities, “low”, “medium”, “high”, and “extreme”. A first order analysis shows no trend on the event frequency for the resulting completion. However, a strong correlation to the Expert Team on Climate Change Detection and Indices (ETCCDI) index R99pTOT—the total precipitation sum above the 99th percentile of precipitation on wet days—seems to be evident.

A catalog of torrential events in Austria since the middle ages

All records in the Austrian torrential event catalog have caused damages and can be roughly classified into (i) events from historical or archival sources and (ii) recent events compiled by scientists of the Austrian Research Centre for Forests (BFW) or reported by engineers of the Forest technical Service of the Austrian Torrent and Avalanche Control (WLV-Austria) in the course of exploratory hazard assessment activities Hübl et al. 2008a, b, 2009, 2010.

One of the historical sources is the “Chronicle of devastations due to floods and torrents, rock avalanches, debris flows and rock falls in Tyrol and Vorarlberg till 1891”, which was compiled by Georg Strele (1861–1950), the director of the Tyrolean provincial headquarter of the Austrian service for torrent and avalanche control from 1904 to 1923. This compilation, referred to as “Strele Chronicle” in the following, consists of natural hazards from the end of the 6th century till the year 1891 for the regions of Tyrol and Vorarlberg. The “Strele chronicle” was digitized by Plank 1995 and integrated into the Austrian torrential event catalog by hubl-ian-2008. Main sources of information were villages, schools or church chronicles, newspaper articles, oral reports, and observations by witnesses as well as experts.

Of similar origin and completing the Austrian torrential event catalog until the beginning of the 20th century is the event chronicle by Stiny 1938. The catalog, referred to as “Stiny chronicle”, contains events especially for the federal states of Salzburg, Upper and Lower Austria, Styria, and Carinthia as reported from the year 792 till the year 1920.

A definite starting point of the systematic collection of more recent torrential events in Austria was the introduction of the “flood reports” in the 1970s. The flood reports have been a framework developed collectively by the Institute of Mountain Risk Engineering (BOKU, Vienna), the WLV-Austria and the BFW, and was used from the year 1972 on to document torrential events. It can be seen as the ancestor of the present Austrian standard as well as international standard in the European Alpine Space for event documentations—defined by the projects DOMODIS “Documentation Of MOuntain DISasters” Hübl et al. 2006 and DIS-Alp “Disaster Information System of ALPine regions” (DIS-Alp) Berger et al. 2007 during the first decade of the 21st century.

The similar data sources of the “Strele Chronicle” and the “Stiny Chronicle” leading to analogical concerns about data quality and biases. Because they are mainly collected in an unsystematic manner and by inexperienced witnesses, uncertainties with regard to the determination of the phenomena and the identification of the process itself are likely. The classification into different process types strongly depends on the specific knowledge of the documenting person, as well on the process itself. While an inexperienced witness maybe able to distinguish between a flood and a debris flow, he may fail in distinguishing between the intermediate processes like bedload transport or debris floods. Other challenges might be changes of meanings for certain terms used for torrential process observations over time, or changes in topographical names. Minor potential biases concern the correct event duration, as events may last for more than 1 day. In this case, the authors used the onset of the event as the event date (Hübl et al. 2008a). Similar uncertainties were encountered concerning the location of the events, reaching from changing village names to information given only at a region wide precision.

However, most concerns of a completeness analyses are uncertainties of the correct timing of the documented events, which result often from the archival nature of the data. For some entries in the chronicles, only the year of the event is given. Other entries only have imprecise information concerning the year like “beginning”, “middle”, or “end” of the decade. In this case, the authors of the compiled Austrian torrential event catalog (Hübl et al. 2009) assigned the first, fifth, or ninth year, e.g., 1921, 1925, 1929 as the event year. Similar vagueness was encountered by the authors concerning the event month, as information on the season, i.e., “spring”, “summer”, “autumn”, or “winter” but not the exact month was available. Here, the authors replaced spring, summer, autumn, and winter by the month of April, August, October, and January (Hübl et al. 2008a).

Completeness analysis

The completeness of an event catalog is equivalent to an unbiased sample and therefore essential for a meaningful analysis. Incompleteness or biased sampling strongly impact the estimated parameters of the assumed models and therefore their interpretation and conclusions.

Problems concerning the completeness of event catalogs were faced in studies in the field of seismology (e.g., Stepp 1972; Nasir et al. 2013; Stucchi et al. 2013) and volcanology (e.g., Wickman 1966; Simkin 1993; Furlan 2010), who studied the number of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. These scientist developed different theories to tackle the problem, which we can utilize for the Austrian catalog of torrential events.

We consider completeness in the context of a torrential event catalog to be given by the reporting rate, which is described as,

with r(t), the reporting rate of year t, \( {\hat{n}}_{\mathrm{t}} \), the number of reported events in year t and nt, the number of actual happened events in year t. A catalog is complete when r(t) = 1, i.e., when all events that actually happened in the year t, have been reported. Although a reporting rate of one is desirable, it is also an unrealistic scenario when compiling torrential processes, especially with respect to the number of small, local events. We therefore define completeness for all possible event sizes by:

A catalog is complete if the yearly number of events is independent of the reporting rate, i.e., that the ratio of the reported events in year t (\( {\hat{n}}_{\mathrm{t}} \)), to the number of all events in year t (nt) is constant for all xtitt and close to one.

Hence, to show that a catalog is complete turns into the equivalent problem of finding the first year τ, for which Eq. (3) permanently holds.

Nevertheless partial completeness, in the sense that r (t) depends on the size of the event, is not an unrealistic assumption—whether for earthquake, volcanic, or torrential event catalogs. Especially high to extreme and to a certain extend medium to low intensity events are likely to be fully reported in modern times, due to an increasing population density (Fuchs et al. 2017), development of standards of documentation schemes (Hübl et al. 2006), technical developments in the realm of remote sensing and an increasing network of monitoring systems (e.g., Hürlimann et al. 2003; Schimmel et al. 2018; Marchi et al. 2002). Additional factors influencing the reporting rate and hence the point in time τ, at which completeness of event catalogs is assumed, are historical events, like the First and the Second World War, the increased public and scientific interest after global economy and ecological changes and the foundation of relevant institutions like the WLV-Austria, the Interpraevent or BFW. The foundation of the WLV-Austria in the year 1884 was a consequence of the widespread devastations in Tyrol and Carinthia in the year 1882. The Interpreavent, an international research society focusing on the protection against floods, debris flows, landslides, rockfall, and avalanches, was founded after the devastating floods and debris flows in Carinthia and Eastern Tyrol in the years 1965 and 1966. The same catastrophe also leads to the foundation of the department concerned with the research on natural hazards at the BFW.

In principle, assessing completeness of historical event catalogs can be divided into two classes, (i) methods based on historical analysis of the information flow from the event itself to the receiver in a dynamic socioeconomic environment (e.g., Stucchi et al. 2009) and (ii) statistical methods which mostly rely on the assumption of stationarity, i.e., assuming that the series of events are produced by a Poisson process (e.g., Stepp 1972; Albarello 2001; Hakimhashemi and Grunthal 2012).

Historical method

Stucchi et al. 2009 uses the appealing dichotomy of “inside” and “outside” of the catalogue to describe the two approaches. In this sense, statistical techniques use internal features of the data while historical methods are concerned with the external factors, factors controlling mainly the quality of the catalogue by influencing the reason, the time and kind of documentation. Historiographical completeness is therefore assessed by the comparison of different historical sources for a given locality, where locality, from this perspective, is interpreted as a “recorder” of events. If the different sources, like chronicles or newspapers, have recorded events of comparable categories like other natural hazards or events of political interest for that locality, it seems unlikely that the hazard under investigation was overlooked—providing the event had a considerable high intensity. On the other hand, if also these other records are missing, an actual data gap seems plausible. The main disadvantages of historical methods, however, are their high resource intensity and their subjectivity, which is considerable lower compared with statistical techniques.

Statistical methods

Statistical methods, although objective, have to assume a generative mechanism for the number of events per year to determinate the year at which the catalog can be assumed complete. The assumption of a generative mechanism, i.e., model, goes hand in hand with a simplification, which is kind of the statistical equivalent to the subjectivity of the historiographic approach.

Cumulative number of events

One widely used assumption is that a number of events per year are generated by a homogeneous Poisson process (e.g., Meyers 2011). Following the statement of a Poisson assumption the cumulative number of events per year shows an linear increase, proportional to the mean of the underlying Poisson distribution Finkelstein 2008 as given in Eq. (4).

with λ(t), the mean number of events after t years and t the number of elapsed years. Breaks in the slope of the cumulative number of events are therefore only possible if λ is changing. Because λ is per definition constant, changes in break must indicate a change in the reporting rate. Nasir et al. 2013, which corresponds to the detection of τ defined by Eq. (3).

Change point detection

The statistical theory on change point detection Truong et al. 2018 for assessing completeness is common in the analysis of volcanic eruption series (e.g., Coles and Sparks 2006; Furlan 2010; Mead and Magill 2014) and is also used for earthquake catalogs (Albarello 2001; Hakimhashemi and Grunthal 2012). The main assumption in change point centered completeness assessment is that the change in the reporting rate is not gradual but abrupt. In general change points are found by using an algorithm to split the event series into non-overlapping periods and a function which characterizes the variability within and between those periods. Albarello-detection-2001 used an exhaustive segmentation and a binomial distributed random variable to characterize the homogeneity within and the heterogeneity between events. Similar, Hakimhashemi-statistical-2012 tested every time point as a possible change point based on the variance of the time between events.

The change point, τ, can then be estimated by means of Bayesian statistics. In this study, we applied three different approaches to test the completeness of the torrential event catalog. The parametric method of Priyadarshana and Sofronov 2012 assumes a negative binomial distribution of the events per year the non-parametric approach follows the proposed methodology described in Haynes et al. 2017, whereas the Bayesian method, based on the natural logarithm of the events per year, follows Chib 1998. For the last method, the threshold of the posterior probability of a true change in mean was set to 0.4.

Standard error

Another quantitative alternative uses the equality of the variance and the mean of a Poisson distributed random variable (Agresti 2007). The maximum likelihood estimate of the mean of a Poisson distributed variable in the context of yearly counts Rychlik and Rydén 2006, is given in Eq. 5.

with λ the mean number of events per year, t1 the first year of observations, tn the last year of observations and nt the number of events in year t. Because of the constant mean per year of a homogeneous Poisson process a similar λ, regardless of the length of the interval T, can be expected. Using this fact, we can estimate the mean for different length intervals T and compare the estimated mean values. In case of stationarity, i.e., the data follows the assumed homogeneous Poisson process; we expect that the means for the different intervals are nearly identical and that the standard error of the mean is inversely proportional to the square root of the length of the interval. The definition of the standard error of the mean, σλ, and using the mentioned equality of the variance and the expectation for the Poisson distribution, lead to Eq. 6.

For different intervals of length T of the catalog, the standard error is then a linear function of Eq. (6), and deviations from the linear function indicate incompleteness of the event catalog (Stepp 1972).

Results

Historiographic results

A purely historiographic threshold for the completeness of the torrential event catalog is difficult to motivate, nevertheless some statements about periods differentiating in number and quality of documentations are possible.

Figure 1 shows the number of actively reporting chronicles (upper panel) and annals (lower panel) in Austria per year from 500 to 1600. The data was compiled from the bayerische-akademie-der-wissenschaften-repertorium-2018, a digital, bibliographic archives of narrative sources provided by the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities. Only annals and chronicles were considered. Especially the years 1100 to 1300 have a great number of reporting annals and chronicles. However, the number of annals decreased in the 13th century, while the number of chronicles, decreased significantly 200 years later.

Actively reporting chronicles (upper panel) and annals (lower pannel) in Austria per year from 500 to 1600. Data is based on Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften 2018

Another equally imported source of historical information is newspapers. The event catalog of the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow, and Landscape Research (WSL), for instance, uses approximately 3000 Swiss newspapers and magazines which are the main source of information on damages caused by floods, debris flows, landslides, and rockfalls (Hilker et al. 2009). However, newspapers can also be an unreliable source because the reporters are, in most cases, not experts on natural hazards. Figure 2 shows the number of actively reporting newspapers and magazines in Austria per year, based on a corpus of 1291 newspapers and magazines published between 1568 and 2018 ANNO/Österreichische Nationalbibliothek 2018. The corpus was reduced to those entries, which mainly reported about events in Austria and operating on a daily or weekly basis. The items were then manually checked if they have at least ten issues, in which articles or reports about torrential processes were published, resulting in a corpus of 164 newspapers and magazines.

Number of actively reporting newspapers and magazines in Austria per year, based on onb-anno/osterreichische-2018. The lower panel shows the distribution of the square root of the deviation of the actual events per year from the mean number of events, estimated for 1800 to 1960. Also shown are the end of the Strele and the Stiny chronicles as well as the establishment of the WLV-Austria, the BFW and start year of the legal obligations for keeping police and school chronicles

The number of daily and weekly published newspapers continuously increases in the middle of the 19th century and reaches a maximum of nearly 80 actively reporting newspapers and magazines at the beginning of the First World War (1914). After the First World War, the number of newspapers and magazines significantly dropped. This is followed by approximately 20 years of an almost stable number of actively reporting newspapers and magazines, after which the number dropped again at the beginning and during the Second World War. After 1945, the number of newspapers and magazines at a daily or weekly publishing cycle stayed nearly constant. For comparison, the end of the Strele and the Stiny chronicles are shown at the top of Fig. (2), as well as the establishment of the WLV-Austria and the BFW. Also shown are the start years of the legal obligations for keeping police and school chronicles. Further, the distribution of the square root of the deviation of the actual events per year from the mean number of events, estimated between 1800 to 1960, is indicated by the lower panel.

Besides historical or at least semi-historical written sources like chronicles, annals, or newspapers also narratives like sagas provide information about the frequency of natural hazards. A typical supernatural reinterpretation of torrential events in sagas is dragons (Petzoldt 2002). These beliefs have their roots in the proto-scientific and early scientific work of the 16th and 17th century, were bones of fossils served as evidence for the existence of dragons (Petzoldt 2003, see article about “Drache”). The association between dragons and debris flows is shown in Fig. 3.

Spatial distribution of sagas related to debris flows depicted as or caused by dragons (red dotted circles), dragons related to natural hazards in general (cyan open circles), dragons with no association to natural hazards (gray-filled circles), and debris flows with no association to dragons (red open squares)

It is based on a corpus of nearly 6800 sagas collected from different sources for whole Austrian Sagen.at 2018. The sagas were searched for common terms referring debris flows as, e.g., “Mure”, “Murgang”, or “Murbruch” and terms referring to dragons and dragon-like creatures e.g. “Drache”, “Lindwurm”, or “Schlange”. The resulting matches were manually checked and classified into “dragons associated with natural hazards”, “dragons associated with debris flows”, “dragons in different contexts” and “debris flows not associated with dragons”. The 182 remaining sagas were located based on municipalities. If the municipality was undefined, the next higher political unit was used. The association of dragons and debris flow is common in Tyrol and Vorarlberg, but still dragons or dragon-like creatures are often associated with natural hazards, especially those resulting from mountain torrents, clearly visible in Fig. 3 for the rest of Austria. Beside dragons also witches, demons (e.g., the “Butz” in Dornbirn, Vorarlberg), or lost souls (e.g., “Salige” in Vent, Tyrol which caused the breach of the ice-dammed Rofener lake), or the devil himself were thought to cause debris flow or flood events.

Beside these torrential hazard specific historical influences on the completeness, also general historical events like the First and the Second World War must be considered. An optimistic estimation from a historiographical perspective would therefore result in a year of completeness after the Second World War (1945). However, a pessimistic estimation corresponds to the introduction year of the flood reports (1972)—similar to the geohydrological event catalog of Blahut et al. 2012.

Statistical results

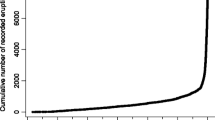

In a first step, the estimation of the beginning year of complete recording, or in other words, the break point τ, is based on a inspection of an abrupt changing in the reporting rate based on the cumulative number of events per years. This leads to a visual break point estimate somewhere between 1940 and 1950 (Fig. 4). It can be further assumed that a linear growth of the report rate is evident since the middle of the 20thcentury.

Estimation of τd by applying the cumulative number of events methodology since the beginning of the event catalog. For the estimation of \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2} \), instationarity of the event distribution left from the related break point is assumed. The x-axis is restricted to the years were approximately linear growth is observed. The upper panel shows the Euclidean distance d (distance of R2 of the linear regressions), indicated by the brown solid line. The distribution of the coefficient of determination for estimating \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2} \) is indicated by the blue dashed line

However, a quantitative estimation of the break point can be derived by successively splitting the catalog into two sub-catalogs. The first split is defined so that at least 3 years of observations are included from the beginning of the catalog. On both sub-catalogs, a linear regression is then fitted to the cumulative number of events per year and the coefficients of determination R2 are calculated. In a further step, the split is shifted 1 year into present and again a linear regression model is fitted against the new disjunctive sub-catalogs. This procedure, splitting, fitting, and shifting, is repeated until the split has reached the years 2015, i.e., 3 years before present. We assume that the break point of the catalog τ is reached when the R2 values of disjunctive sub-catalogs having a minimal Euclidean distance d to the perfect solution.

Figure 4 shows the Euclidean distance d of R2 to r(t) ≈ 1 for the whole torrential event catalog over the reported years in the upper panel. After a phase of fluctuations due a low number of observations, d stabilizes, reaching its minimum at τd = 1925.

If we are assuming in stationarity (c.f. Eq. 4) for the event distribution of the left sub-catalogs, the estimation of the break point of completeness is then based on finding the maximum coefficient of determination for the regressionmodel of the right sub-catalog. Hence, using the maximum R2 of the linear fit for the right half of the sub-catalogs, results in \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2}=1942 \) (see dashed line in the upper panel of Fig. 4).

By applying the quantitative estimation of the break point as described above, we further differentiated between four different intensity classes as well as three torrential process types (shown in Figs. 5 and 6).

Estimated τd and \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2} \), differentiated by intensities. The x-axis are restricted to the years were approximately linear growth is observed. The upper panel shows the Euclidean distance d, indicated by the red solid line. The distribution of the coefficient of determination for estimating \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2} \) is indicated by the cyan-dashed line

Estimated τd and \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2} \), differentiated by torrential processes. The x-axis are restricted to the years were approximately linear growth is observed. The upper panel shows the Euclidean distance d, indicated by the t color cluster 1 red solid line. The distribution of the coefficient of determination for estimating \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2} \) is indicated by the cyan dashed line

Completeness of the event catalog considering only 4910 low intensity events, resulted in \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2}=1933 \). For 6197 medium intensities events, τd = 1921 respectively \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2}=1931 \) could be assumed. Regarding 3154 high intensities events, τd = 1937 as well as \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2}=1929 \) is obtained. Finally, for 1011 events observed in the extreme intensity class, a completeness of the catalog is related to the assumption of τd = 1938 respectively \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2}=1929 \).

Considering solely flood events (8579), a completeness of the torrential catalog could be assumed with τd = 1919 respectively \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2}=1938 \). For 6462 bedload events, completeness analyses resulted in τd = 1926 and \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2}=1947 \), whereas τd = 1925 respectively \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2}=1921 \) for 6386 debris flow events.

Applying change point detection with all methods (parametric, non-parametric as well as Bayesian), the most present detected change point was assumed to coincidence with the year of completeness. This assumption resulted for the parametric method in τP = 1920, for the non-parametric method in τN = 1948 and for the Bayesian method in τB = 1919.

According to the standard error method described by stepp-analysis-1972 and following Eq. (6), the catalog can be assumed to be complete for the last 35 years, i.e., since τσ = 1984 (Fig. 7).

Standard error of the mean against the length of the record since the year 2017 on a double, decimal logarithmic, i.e., base of 10, scale. If a number of events per interval T are generated by a homogeneous Poisson process, which is assumed to correspond with a complete record, than the standard error should follow the black solid line. This behavior is approximately evident until 35 from 2017, which results in a rather short complete record since 1982

The short period resulting from the standard error is a consequence of its conservative behavior and would mean to lose a considerable amount of data.

Overall completeness results

Overall results of completeness are based on historiographical information, the cumulative number of event methodology and on the change point detection methods. For the later, parametric and non-parametric as well as Bayesian approaches are considered. Because of its instability, results from the standard error method have been excluded.

Figure 8 gives an overview of the estimated years of completeness based on the statistical methods, for the whole catalog and differentiated by intensities and process types.

Overview of the estimated years of completeness based on the statistical methods, for the whole catalogue and differentiated by intensities and process types. A statistical based completeness for the whole dataset refers to 〈τ〉 = 1931 ± 13. Considering the historiographic results within this study, a final year of completeness of the Austrian torrential event catalogue is given with τ* = 1945. The error bars are ± one standard deviation for the different statistical models used

Final year of completeness of the Austrian torrential event catalog is given with τ∗ = 1945. The error bars are ± one standard deviation for the different statistical models used.

Summarizing the results of τd, \( {\tau}_{{\mathrm{R}}^2} \), τP, τN, and τB, a statistical based completeness can be assumed with ⟨τ = 1931 ± 13. Similar results are obtained for different intensity classes with mean years of completeness of low intensities: τ = 1941 ± 7, medium intensities: τ = 1927 ± 11, high intensities: τ = 1917 ± 23 and extreme intensities: τ = 1927 ± 17. Overall completeness of the catalog, differentiated by process types, can be assumed for flood events with τ = 1921 ± 3, for bedload events with ⟨τangle = 1943 ± 12 and for debris flow events with τ = 1934 ± 12.

However in combination with the historiographic analyses (indicating completeness somewhere between 1945 to 1972), we finally propose the year of completeness of the Austrian torrential catalog with τ∗ = 1945.

Above information is based on a constant year of completeness assumption for whole Austria. Figure 9 shows, however, a regional diversity of the completeness for the torrential event catalog, based on a 50 km by 50 km raster.

Spatial distribution of the completeness of the Austrian torrential event catalog based on a 50 km by 50 km raster. Each cell gives the completeness year, averaged from the median results of the cumulative number of events and the change point methods, based on the event series lying within the cell

Here, for each cell the completeness year is averaged from the statistical results of the cumulative number of events as well as the change point methods, based on the event series lying within this cell. It is evident that the mountainous regions like Vorarlberg, western Tyrol, as well as parts of Salzburg, Styria, and Carinthia have the longest, complete series of events, starting with the years 1930 or even 1910. The missing areas, almost entirely on the edge of the Alps, have the shortest complete catalogs with length of 12 to 37 years.

Discussion

The statistical methods agree upon a year of completeness, for the whole catalog, between 1925 to 1985, but most values cluster around 1940, except the value resulting from the method described by stepp-analysis-1972. Similar clustering around the first half of the 20th century is also observed, regardless if the catalog is divided by process or intensities. In contrast, the historiographic approach does not imply completeness before 1945, and hence a dissonance between the both methods exists, which can be explained by the different frames of discernment.

The holistic perspective of the historiographic method assumes social stability as a basic requirement to allocate resources for an event documentation and ignores, unlike the statistical approach, the possibility of individual completeness of certain regions. Completeness of the Austrian torrential event catalog seems therefore to be unplausible during and in between the two world wars.

Hence the year 1945 is a compromise between the suggestions from the statistical as well as historiographic approaches, which results in a 73 year long documentation period and 15,255 torrential events for whole Austria (out of more than 21,000 registered torrential events since year 544).

Documentations before year 1945 can highlight possible catastrophic events in the sense of what can happen in a certain region—reflecting ranges of possibilities. However, these documentations cannot be used to describe the dynamics of the number of events, because of their discrete nature.

Historical information are particularly interesting if they deviate from, or correspond to, a long-term mean within the completeness period, calculated by Eq. 7.

where \( {\tilde{n}}_i \) is the anomaly in year i, ni is the number of events in year i, and <n> is the mean number of events per year, i.e., the arithmetic mean of the number of events per year, estimated according to Eq. (5), with t1 = τ∗ and tn = 2017. The scaled anomalies are the yearly anomalies divided by the standard deviation of the yearly anomalies as given in Eq. (8).

where zi is the scaled anomaly of year i and s is the standard deviation of the yearly number of events estimated as usual. The advantage of the scaled anomalies is that they are dimensionless, but on a scale in terms of multiples of the standard deviation, and therefore are easily compared with other similar treated measurements. Note that the scaled anomalies are equivalent to the standard or z-scores commonly used in statistics Schiller et al. 2011.

Figure 10 shows the scaled yearly anomalies (Eq. 7) on a base 10 logarithmic scale, for all events in the completeness period, 1945 to 2017. Remarkable are the high numbers of events in the years 1959, 1965, 1966, 1991, 2002, 2005, and 2013 exceeding one and a half standard deviations. These high number years are balanced by the low number years 1984, 1988, 2001, 2003, and 2011 with number of events falling below on half standard deviation. A slight trend in time is indicated in by a local polynomial regression line. However, according to the bootstrapped 95% confidence region of the smoother, also stationarity is plausible, which is confirmed by a Mann–Kendal test with a p value of 0.39.

Scaled yearly anomalies (black line), i.e., z-scores (Eq. 7), of the decadic logarithm of the number of events from 1945 to 2017. The decadic logarithm was used to damper the variability in the number of events. A slight trend in time, as indicated by the local polynomial regression (incl. bootstrapped 95% confidence region), is rejected, based on a Mann–Kendal test with a p value of 0.39

Another important, socially relevant topic, is the question of future increase (or decrease) of natural disasters due to predicted climate change. Many authors have suggested changes of the frequency of natural hazard processes in steep headwater catchments such as landslides or debris flows (Wieczorek and Glade 2005; Borgatti and Soldati 2010; Crozier 2010; Stoffel et al. 2014; Youberg et al. 2014), sediment transport (Schneider et al. 2014), or floods (Beniston and Stoffel 2016). However, due to the lack of historical event data, many of those studies rely on modeling event-triggering factors, such as critical precipitation, assuming a strong correlation with the occurrences of torrential events.

If we consider the scaled yearly anomalies for all events in the completeness period, starting in 1945, and compare it with the annual total precipitation observed above the long-term 99th percentile of precipitation on wet days (R99pTOT), we might assume a strong correlation (Fig. 11). To estimate R99pTOT—an ETCCDI index proposed by Karl et al. 1999—precipitation data on a daily basis was used, (i) based on measurements from the “Historical, Instrumental, Climatological, Surface Time Series of the greater ALPine region (HISTALP)” project (Auer et al. 2007) and (ii) based on stations operated by the Hydrographic Services (HD) Austria. All daily observations were transformed into anomalies (Eq. 8) using the mean of the period 1961 to 1990 for the HISTALP and mean of the period 1971 to 2000 for the HD stations. The daily measurements were temporally aggregated into yearly anomalies and spatially into means for whole Austria.

Scaled yearly anomalies (black solid lines) of the decadic logarithm of the number of events from 1945 to 2017 compared with the scaled yearly anomalies of the annual total precipitation observed above the long-term 99th percentile of precipitation on wet days, R99pTOT (blue dashed lines). Calculation of anomalies are based on Eq. (7)

However, the first order analyses, based on the proposed completeness period of the torrential event catalog, suggest further studies to face the challenge in understanding magnitude and frequency of torrential events in a changing environment.

Conclusion

The Austrian torrential event catalog provides useful information on historical events. The completeness analyses, based on a robust investigation, allow future investigations in many fields dealing with natural hazardous processes in torrential catchments. In the case of hazard assessment, magnitude-frequency analyses and evaluation of mitigation measures can be supported. Further, effects of changes in the environmental characteristics of steep headwater catchments can be related to specific periods in the past. Finally, a long period of complete event documentations facilitates risk governance and allows new forms of risk-communication to a broader audience, as an alternative to the concept of return period, which is often prone to misconceptions and misuses (Serinaldi 2015).

References

Agresti A (2007) An introduction to categorical data analysis, 2nd edn. Wiley series in probability and mathematical statistics. Wiley-Interscience, Hoboken

Albarello D (2001) Detection of space and time heterogeneity in the completeness of a seismic catalog by a statistical approach: an application to the Italian area. Bull Seismol Soc Am 91(6):1694–1703. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120000058

ANNO/Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (2018) URL http://anno.onb.ac.at. Accessed 4 Nov 2018

Auer I, Böhm R, Jurkovic A, Lipa W, Orlik A, Potzmann R, Schöner W, Ungersböck M, Matulla C, Briffa K, Jones P, Efthymiadis D, Brunetti M, Nanni T, Maugeri M, Mercalli L, Mestre O, Moisselin JM, Begert M, Müller-Westermeier G, Kveton V, Bochnicek O, Stastny P, Lapin M, Szalai S, Szentimrey T, Cegnar T, Dolinar M, Gajic-Capka M, Zaninovic K, Majstorovic Z, Nieplova E (2007) HISTALP—historical instrumental climatological surface time series of the Greater Alpine Region. Int J Climatol 27(1):17–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1377

Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften (2018) Repertorium Geschichtsquellen des deutschen Mittelalters. URL https://www.geschichtsquellen.de. Accessed 4 Nov 2018

Beniston M, Stoffel M (2016) Rain-on-snow events, floods and climate change in the alps: events may increase with warming up to 4 °C and decrease thereafter. Sci Total Environ 571:228–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.07.146 cited By 12

Berger E, Grisotto S, Hübl J, Kienholz H, Kollarits S, Leber D, Loipsberger A, Marchi L, Mazzorana B, Moser M, Nössinger T, Riedler W, Scheidl C, Schmid F, Schnetzer I, Siegel H, Volk G (2007) DIS-ALP: disaster information system of alpine regions - final report. Tech Rep 101, INTERREG IIIB - Alpine Space, URL http://www.alpine-space.org/2000-2006/dis-alp.html. Accessed 4 Nov 2018

Blahut J, Poretti I, De Amicis M, Sterlacchini S (2012) Database of geo-hydrological disasters for civil protection purposes. Nat Hazards 60(3):1065–1083. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-011-9893-6

Borgatti L, Soldati M (2010) Landslides as a geomorphological proxy for climate change: a record from the Dolomites (northern Italy). Geomorphology 120(1–2):56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.09.015 00058

Chib S (1998) Estimation and comparison of multiple change-point models. J Econ 86(2):221–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(97)00115-2

Coles S, Sparks RSJ (2006) Extreme value methods for modelling historical series of large volcanic magnitudes. In: Mader HM, Coles SG, Connor CB, Connor LJ (eds) Statistics in volcanology, special publications of the IAVCEI, vol 1. Geological Society, London, pp 47–56

Crozier MJ (2010) Deciphering the effect of climate change on landslide activity: a review. Geomorphology 124(3–4):260–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2010.04.009 00100

Duile J (1826) Über Verbauung der Wildbäche in Gebirgsländern, vorzüglich in der Provinz Tirol und Vorarlberg. Innsbruck

Finkelstein M (2008) Failure rate modelling for reliability and risk. Springer series in reliability engineering. Springer, London

Forest Act (1975) Bundesgesetz vom 3. Juli 1975, mit dem das Forstwesen geregelt wird StF: BGBl. Nr. 440/1975 (NR: GP XIII RV 1266 AB 1677 S. 150. BR: 1392 AB 1425 S. 344.)

Fuchs S, McAlpin MC (2005) The net benefit of public expenditures on avalanche defence structures in the municipality of Davos, Switzerland. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 5(3):319–330. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-5-319-2005

Fuchs S, Kaitna R, Scheidl C, Hübl J (2008) The application of the risk concept to debris flow hazards. Geomechanik und Tunnelbau 1(2):120–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/geot.200800013

Fuchs S, Röthlisberger V, Thaler T, Zischg A, Keiler M (2017) Natural hazard management from a coevolutionary perspective: exposure and policy response in the European Alps. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 107(2):382–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2016.1235494

Furlan C (2010) Extreme value methods for modelling historical series of large volcanic magnitudes. Statistical Modelling: An International Journal 10(2):113–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471082X0801000201

Hakimhashemi AH, Grunthal G (2012) A statistical method for estimating catalog completeness applicable to long-term nonstationary seismicity data. Bull Seismol Soc Am 102(6):2530–2546. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120110309

Haynes K, Fearnhead P, Eckley IA (2017) A computationally efficient nonparametric approach for change point detection. Stat Comput 27(5):1293–1305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11222-016-9687-5

Hilker N, Badoux A, Hegg C (2009) The Swiss flood and landslide damage database 1972-2007. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 9(3):913–925. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-9-913-2009

Hübl J, Kienholz H, Loipersberger A (2006) DOMODIS: Dokumentation alpiner Naturereignisse [Documentation of Mountain Disasters]. Tech. rep., Interpreavent, Klagenfurt, URL http://www.interpraevent.at/. Accessed 4 Nov 2018

Hübl J, Totschnig R, Scheidl C (2008a) IAN Report 111: Historische Ereignisse Band 1 Auswertung von Wildbach Schadereignissen bis 1891 auf Basis der Brixner Chronik. Forschungsbericht 111, Institut für Alpine Naturgefahren, Wien, Österreich, URL https://www.baunat.boku.ac.at/ian/forschung/reports-forschungsberichte/. Accessed 4 Nov 2018

Hübl J, Totschnig R, Sitter F, Mayer B, Schneider A (2008b) IAN Report 111: Historische Ereignisse Band 2 Auswertung von Wildbach Schadereignissen in Westösterreich auf Grundlage der Wildbachaufnahmeblätter. Forschungsbericht 111, Institut für Alpine Naturgefahren, Wien, Österreich, URL https://www.baunat.boku.ac.at/ian/forschung/reports-forschung sberichte/, (accessed 4 November 2018)

Hübl J, Totschnig R, Sitter F, Schneider A, Krawtschuk A, Dusl G, Fischer N, Swoboda P, Neckel N (2009) IAN Report 111: Historische Ereignisse Band 3 Auswertung von Wildbach Schadereignissen in österreich auf Grundlage der Wildbachaufnahmeblätter. Forschungsbericht 111, Institut für Alpine Naturgefahren, Wien, Österreich, URL https://www.baunat.boku.ac.at/ian/forschung/reports-forschungsberichte/, (accessed 4 November 2018)

Hübl J, Totschnig R, Sitter F, Schneider A, Krawtschuk A (2010) IAN Report 111: Historische Ereignisse Band 4 Zusammenstellung und Analyse dokumentierter Ereignisse in österreich bis 2009. Forschungsbericht 111, Institut für Alpine Naturgefahren, Wien, Österreich, URL https://www.baunat.boku.ac.at/ian/forschung/reports-forschung sberichte/, (accessed 4 November 2018)

Hürlimann M, Rickenmann D, Graf C (2003) Field and monitoring data of debris-flow events in the Swiss Alps. Can Geotech J 40(1):161–175. https://doi.org/10.1139/t02-087

Karl TR, Nicholls N, Ghazi A (1999) CLIVAR/GCOS/WMO workshop on indices and indicators for climate extremes workshop summary. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9265-9_2

Keiler M, Fuchs S (2016) Vulnerability and exposure to geomorphic hazards: some insights from the European Alps. In: Meadows ME, Lin JC (eds) Geomorphology and society. Springer Japan, Tokyo, pp 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-56000-5_10

Landolt E (1886) Die Bäche, Schneelawinen und Steinschläge und die Mittel zur Verminderung der Schädigungen durch dieselben. Schweizerischer Forstverein, Zürich

Marchi L, Arattano M, Deganutti AM (2002) Ten years of debris-flow monitoring in the Moscardo Torrent (Italian Alps). Geomorphology 46(1–2):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-555X(01)00162-3

Mayer B, Stoffel M, Bollschweiler M, Hübl J, Rudolf-Miklau F (2010) Frequency and spread of debris floods on fans: a dendrogeomorphic case study from a dolomite catchment in the Austrian Alps. Geomorphology 118(1):199–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.12.019

Mead S, Magill C (2014) Determining change points in data completeness for the Holocene eruption record. Bull Volcanol 76(11). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-014-0874-y

Meyers RA (2011) Extreme environmental events: complexity in forecasting and early warning. Springer reference. Springer, New York

Müller F (1857) Die Gebirgs-Bäche und ihre Verheerungen, wie die Mittel zur Abwendung der Letzteren. Krüll'sche Universitäts-Buchhandlung, Landshut

Nasir A, Lenhardt W, Hintersberger E, Decker K (2013) Assessing the completeness of historical and instrumental earthquake data in Austria and the surrounding areas. Aust J Earth Sci 106(1):90–102

Petzoldt L (2002) Einführung in die Sagenforschung, 3rd edn. No. 2353 in UTB Kulturwissenschaft, UVK-Verl.-Ges, Konstanz

Petzoldt L (2003) Kleines Lexikon der Dämonen und Elementargeister, 3rd edn. No. 427 in Beck’sche Reihe, Beck, München

Plank J (1995) Chronik der Wildbachschäden in Österreich bis zum Jahre 1891 und umfassende Dokumentation anhand von zwei Beispielen (Enterbach-Inzing, Niedernsiller Mühlbach). Master’s thesis. In: University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences. Wien, Vienna

Priyadarshana M, Sofronov G (2012) A modified cross entropy method for detecting multiple change points in DNA Count Data. In: 2012 IEEE congress on evolutionary computation, IEEE, Brisbane, Australia, pp 1–8. doi https://doi.org/10.1109/CEC.2012.6256470

Procter E, Bollschweiler M, Stoffel M, Neumann M (2011) A regional reconstruction of debris-flow activity in the northern calcareous alps, Austria. Geomorphology 132(1):41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.04.035

Regulation: Hazard Zone Maps (1976) BGBl 436/1976

Rychlik I, Rydén J (2006) Probability and risk analysis: an introduction for engineers. Springer, Berlin

Sagen.at (2018) Traditionelle Sagen aus Österreich. URL http://sagen.at/texte/sagen/oesterreich/sagen_oesterreich.h tm, (accessed 4 November 2018)

Schiller J, Srinivasan R, Spiegel M (2011) Schaums outline of probability and statistics. Schaum’s outline series, McGraw-Hill Education

Schimmel A, Hübl J, McArdell B, Walter F (2018) Automatic identification of alpine mass movements by a combination of seismic and infrasound sensors. Sensors 18(5):1658. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18051658

Schneider J, Redtenbacher M, Harb G, Sass O, Stangl J, Gobiet A, Heinrich G, Tani S (2014) Monitoring of sediment transport processes for determining future trends. In: Schleiss A, De Cesare G, Franca MJ, Pfister M (eds) Proceedings of the international conference on fluvial hydraulics, RIVER FLOW 2014. CRC Press, Balkema, pp 1921–1928. https://doi.org/10.1201/b17133

Schraml K, Kogelnig B, Scheidl C, Stoffel M, Kaitna R (2013) Estimation of debris flood magnitudes based on dendrogeomorphic data and semi-empirical relationships. Geomorphology 201:80–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2013.06.009

Serinaldi F (2015) Dismissing return periods! Stoch Env Res Risk A 29(4):1179–1189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-014-0916-1

Simkin T (1993) Terrestrial volcanism in space and time. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 21(1):427–452. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ea.21.050193.002235

Smith K, Petley DN (2009) Environmental hazards: assessing risk and reducing disaster, 5th edn. Routledge, Milton Park, Abingdon

Stepp JC (1972) Analysis of completeness of earthquake sample in the Puget Sound area and its effect on statistical estimates of earthquake hazard. Tech. Rep. 80302, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Environmental Research Laboratories, Boulder, Colorado

Stiny J (1907) Das Murenphänomen. Mitteilung des deutschen Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereines beider Hochschulen in Graz. Graz

Stiny J (1909) Die Ursachen der vorjährigen Vermurungen im Zillertal. Mitteilung der Geologischen Gesellschaft, Wien

Stiny J (1938) Über die Regelmäßigkeit der Wiederkehr von Rutschungen, Bergstürzen und Hochwasserschäden in österreich. Geologie und Bauwesen (2):10–48

Stoffel M, Mendlik T, Schneuwly-Bollschweiler M, Gobiet A (2014) Possible impacts of climate change on debris-flow activity in the Swiss Alps. Clim Chang 122(1–2):141–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0993-z cited By 35

Stucchi M, Albini P, Mirto M, Rebez A (2009) Assessing the completeness of Italian historical earthquake data. Ann Geophys (2–3). DOI https://doi.org/10.4401/ag-3330

Stucchi M, Rovida A, Gomez Capera AA, Alexandre P, Camelbeeck T, Demircioglu MB, Gasperini P, Kouskouna V, Musson RMW, Radulian M, Sesetyan K, Vilanova S, Baumont D, Bungum H, Fäh W, Lenhardt K, Makropoulos JM, Martinez Solares O, Scotti M, Živčić P, Albini J, Batllo C, Papaioannou R, Tatevossian M, Locati C, Meletti D, Viganò D, Giardini D (2013) The SHARE European Earthquake Catalogue (SHEEC) 1000-1899. J Seismol 17(2):523–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10950-012-9335-2

Thaler T, Attems MS, Bonnefond M, Clarke D, Gatien-Tournat A, Gralepois M, Fournier M, Murphy C, Rauter M, Papathoma-Köhle M, Servain S, Fuchs S (2019) Drivers and barriers of adaptation initiatives - How societal transformation affects natural hazard management and risk mitigation in Europe. Sci Total Environ 650:1073–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.306

Truong C, Oudre L, Vayatis N (2018) A review of change point detection methods. Signal Processing. Under Review.

Wickman FE (1966) Repose-period patterns of volcanoes I-IV. Arkiv fäor Mineralogi och Geologi 4:291–352

Wieczorek GF, Glade T (2005) Climatic factors influencing occurrence of debris flows. In: Debris-flow hazards and related phenomena. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, pp 325–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-27129-5_14

Wilhelm C (1996) Wirtschaftlichkeit im Lawinenschutz: Methodik und Erhebungen zur Beurteilung von Schutzmassnahmen mittels quantitativer Risikoanalyse und ökonomischer Bewertung. PhD thesis, ETH Zurich

WLK digital event catalogue (2018) URL https://naturgefahren.die-wildbach.at, (Accessed 8 November 2018)

Youberg AM, Webb RH, Fenton CR, Pearthree PA (2014) Latest Pleistocene-Holocene debris flow activity, Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona; implications for modern debris-flow hazards under a changing climate. Geomorphology 219:87–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2014.04.034

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU). The authors are grateful to the Agency for Spatial Information of the Forest Technical Service for Avalanche and Torrent Control of Austria, for providing data for this project and the six anonymous reviewers, as well as Jan Blahut for investing their time to significantly improve the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Heiser, M., Hübl, J. & Scheidl, C. Completeness analyses of the Austrian torrential event catalog . Landslides 16, 2115–2126 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-019-01218-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-019-01218-3