Abstract

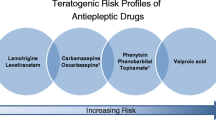

In light of the increased awareness of the teratogenic risks with older-generation antiseizure medications (ASMs) and the introduction of many new drugs, prospective antiepileptic drugs and pregnancy registries were introduced some 25 years ago by various independent research groups. The overall aim of these registries is to compare different treatment alternatives with respect to the risk of major congenital malformations (MCM) in the exposed offspring and thus facilitate rational, evidence-based management of women with epilepsy and childbearing potential. The UK and Ireland Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register, the North American AED Pregnancy Registry, EURAP (The International Antiepileptic Drugs and Pregnancy Registry), the Raoul Wallenberg Australian Pregnancy Register, and the Kerala Registry of Epilepsy and Pregnancy are the most important registries established for assessment of specifically the safety of ASMs. Since it is the largest, and being initially European based, EURAP is the focus of this overview of the contribution of pregnancy registries over the years. EURAP and the other registries have provided important information on pregnancy outcomes with the most frequently used ASMs in monotherapy, thereby identifying higher prevalence of MCMs with valproate and topiramate, whereas the risk appears low with lamotrigine and levetiracetam. Further, for several ASMs the risk appears to be dose-dependent. The registries continue to play an important role in efforts to assess the safety of the newer ASMs and of specific combination therapies. Unlike administrative population-based registries, these specific prospective ASM registries also include important information on the mothers’ epilepsy and seizure control.

Zusammenfassung

Vor etwa 25 Jahren wurden erstmals von unterschiedlichen unabhängigen Forschergruppen prospektive Schwangerschaftsregister eingeführt, da sich das Bewusstsein für ein erhöhtes Fehlbildungsrisiko der älteren Antianfallsmedikamente (AAM) erhöhte und zudem zahlreiche neue Medikamente auf den Markt kamen. Das allgemeine Ziel der einzelnen Schwangerschaftsregister ist es, unterschiedliche Behandlungsalternativen bei einem möglichen Risiko für große kongenitale Fehlbildungen (MCM) bei Neugeboren von Müttern unter AAM zu vergleichen und ein rationales evidenzbasiertes Management bei Frauen mit Epilepsie und Kinderwunsch zu ermöglichen. Ausdrücklich für die Einschätzung der Sicherheit der AAM sind die bedeutendsten Register das UK and Ireland Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register, das North American AED Pregnancy Registry, EURAP (The International Antiepileptic Drugs and Pregnancy Registry), das Raoul Wallenberg Australian Pregnancy Register und das Kerala Registry of Epilepsy and Pregnancy. EURAP, initial lediglich in Europa etabliert, ist mittlerweile das größte Register und bildet den Fokus dieser Übersicht über Beiträge von Schwangerschaftsregistern über die Jahre. EURAP und die anderen Schwangerschaftsregister lieferten bislang wichtige Informationen zu Schwangerschaftsresultaten für die meisten verwendeten AAM in Monotherapie. Es wurde eine höhere Prävalenz für MCM unter Valproat und Topiramat beschrieben, während das Risiko unter Lamotrigin und Levetiracetam niedrig erscheint. Darüber hinaus scheint das erhöhte Risiko einzelner AAM dosisabhängig zu sein. Die Schwangerschaftsregister werden weiterhin eine wichtige Rolle bei den Bemühungen spielen, die Sicherheit von neuen AAM und Kombinationen einschätzen zu können. Im Gegensatz zu administrativen populationsbasierten Registern enthalten diese spezifischen prospektiven AAM-Register auch wichtige Informationen über mütterliche Epilepsien und die Anfallskontrolle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Out of 70 million persons with epilepsy around the world, at least 15 million are women of child-bearing age [1]. Based on 130,000,000 annual live births globally (www.indexmundi.com) and the assumption that women with epilepsy account for 0.5% of these figures, it can be estimated that approximately 650,000 children are born to women with epilepsy every year. Safe pregnancy for women with epilepsy is thus not just a priority for the individual woman with epilepsy but also a major public health issue.

The possibility that antiseizure medications (ASMs) may be teratogenic has been a concern ever since the first report more than 50 years ago of six children with hare-lip and cleft palate who had been exposed to different ASMs during pregnancy [2]. Many subsequent studies have confirmed an increased prevalence of major congenital malformations (MCMs) in offspring of women with epilepsy and that this is mainly related to exposure to ASM rather than being associated with the maternal epilepsy [3].

The fact that epilepsy is a serious condition [4], and that most women with active epilepsy need to maintain an effective treatment also during pregnancy, has highlighted the need to identify safer treatment options for women with epilepsy who are of childbearing potential. Studies aiming to assess and compare pregnancy outcomes in relation to exposure to different ASMs face many challenges: First, since randomized studies of teratogenic risks are unethical and not an option, we are restricted to observational studies with inherent risks of confounding. Second, teratogenic outcomes such as MCMs are, fortunately, uncommon. A final challenge is the number of treatment options with more than 25 different ASMs available and countless ASM combinations. In conclusion, studies aimed at comparing the risk of MCMs with different ASM treatments require large cohorts with sufficiently detailed and reliable data to control for possible confounding. To meet these requirements, and in the light of the introduction of several new ASMs, independent groups launched prospective antiepileptic drugs and pregnancy registries in the late 1990s [5].

Types of pregnancy registries

Most of these specific epilepsy and pregnancy registries have similar overall objectives, i.e., to assess the risk of MCMs after prenatal exposure to ASMs. They may differ in the way they enroll pregnant women and in the follow-up time after delivery as well as regarding the definition of MCMs; generally, however, women are included in early pregnancy, before outcome is known, and thereafter followed up prospectively, and the offspring is assessed at birth and during follow-up up to 1 year of age [5].

Some registries, e.g., the International Lamotrigine Pregnancy Registry and the US Levetiracetam Pregnancy Registry, have been set up by pharmaceutical companies and only collect data on the manufacturers’ own product. Although these registries can provide some useful information, their value is severely limited by the lack of a comparator ASM, and both of the aforementioned registries were closed after some years [6, 7].

Independent registries enrolling pregnancies with exposure to any ASM are more informative as they provide comparisons of risks between different treatments. The most important are the UK and Ireland Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register, the North American AED Pregnancy Registry (NAAPR), EURAP (The International Antiepileptic Drugs and Pregnancy Registry), the Raoul Wallenberg Australian Pregnancy Register (APR), and the Kerala Registry of Epilepsy and Pregnancy. As indicated by their names, most of these registries are nation- or region-based, whereas EURAP enrolls pregnancies from different countries in Europe and beyond. EURAP also receives data on pregnancies from APR and Kerala given the similarities between these three registries. Having enrolled more than 29,000 pregnancies with exposure to ASMs (www.eurapinternational.org), EURAP is the largest among these prospective ASM-specific registries and represents the focus of this overview. EURAP was established in the first centers in some European countries and has since then gradually expanded to include more centers and countries, now involving more than 40 countries in Europe, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and Africa (Fig. 1). Women taking ASMs at the time of conception, irrespective of the indication, may be included, but so far the indication for use of ASMs has been epilepsy in 99% of the pregnancies. To avoid selection bias, only pregnancies recorded before fetal outcome is known and within week 16 of gestation are included in the prospective risk assessment. EURAP relies on enrollment through regional and national networks of collaborating physicians who enroll and follow up the pregnant women. These physicians submit regular reports to the central registry in Milan, Italy, each trimester and after delivery, as well as a final report of the outcome of the offspring at 1 year after birth.

Contribution of epilepsy and pregnancy registries

The epilepsy and pregnancy registries have been operational for some 25 years and have made major contributions to our understanding of the comparative safety of different ASMs and of other related aspects. As already mentioned, the outcome of primary interest in these registries is MCMs, and the prevalence of MCMs after exposure to monotherapy of the eight most frequently used ASMs has been published [8,9,10,11,12]. The absolute risk in terms of prevalence of MCMs with specific ASMs may differ slightly between the registries presumably mainly due to differences in methodologies, but the overall pattern is very similar across registries when it comes to comparisons between ASMs. Valproate is consistently associated with the highest prevalence of MCMs, whereas lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and possibly oxcarbazepine are associated with the lowest risks (Table 1).

The registries have also shown that for some ASMs the risk of MCMs is dose dependent. The EURAP registry reported a higher prevalence of MCMs with increasing doses at the time of conception for valproate, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine [15]. In a subsequent publication, EURAP provided comparisons of MCM risk between different ASMs at different dose levels to assist in the individual risk assessments and evidence-based treatment selection [12].

Being multinational, EURAP has the opportunity to compare ASM use during pregnancy between the participating countries, and an early publication revealed significant differences with regard to proportion using polytherapy as well as using first-generation ASMs [16]. Furthermore, changes in ASM selection over time have been analyzed. Over a 14-year period, the use of valproate and carbamazepine during pregnancy decreased markedly whereas the proportion of treatments with lamotrigine and levetiracetam increased [17]. In parallel with this shift in ASM use, the prevalence of MCMs declined by approximately 25%, indicating the benefits associated with the use of these newer-generation ASMs [17]. Interestingly, there was no indication of a higher rate of pregnancies with uncontrolled tonic–clonic seizures associated with this change in drug selection. However, the impact on seizure control may be different if switches or withdrawals are carried out during pregnancy rather than being completed well in advance of conception. A EURAP analysis of pregnancies where valproate was withdrawn or switched to another ASM during the first trimester showed that, compared with those who continued on valproate, the risk of major convulsive seizures was doubled (33% among withdrawals, 29% among switchers, vs. 16% among those with maintained use of valproate; [18]).

Most of the data from the pregnancy registries are on ASM monotherapies. An analysis of data from NAAPR, the UK Ireland Pregnancy Register, and the International Lamotrigine Pregnancy Registry demonstrated the importance of considering the type of ASMs included in polytherapy rather than just the number of drugs [19]. It appeared from this analysis that it was the inclusion of valproate in the combination therapy that was driving the higher prevalence of MCMs in polytherapy. The risk was much higher when carbamazepine or lamotrigine was combined with valproate compared with a combination of lamotrigine and carbamazepine or lamotrigine with any non-valproate ASM [19]. A more detailed analysis of MCM risks with valproate in monotherapy and in combination with lamotrigine or with other ASMs was carried out based on EURAP data [20]. Whether in monotherapy or combination therapy, the MCM risk increased with the dose of valproate. Interestingly, the prevalence of MCM when valproate at the lowest dose category (< 700 mg/day) was combined with lamotrigine (7.0%) or with any other ASM (5.4%) appeared to be lower than with valproate in monotherapy at a higher dose level (11% at doses 700–1500/day; and 24% at > 1500 mg/day; [20]).

EURAP and some other specific epilepsy and pregnancy registries prospectively collect information on seizures during pregnancy. In a first report [21] of 1956 pregnancies of 1882 women with epilepsy, 58% were seizure-free throughout pregnancy. There were 36 cases of status epilepticus (12 convulsive), which resulted in stillbirth in one case, but no cases of miscarriage or maternal mortality. A subsequent report focused on 3806 pregnancies of 3451 women on ASM monotherapy for their epilepsy [22]. Of all cases, 67% remained seizure-free throughout pregnancy. Generalized tonic–clonic seizures occurred in 15% of the pregnancies. Women with idiopathic generalized epilepsies were more likely to remain seizure-free (74%) than women with localization-related epilepsy (60%). There were 21 cases of status epilepticus (10 convulsive): none with maternal mortality and only one with a subsequent stillbirth.

Contribution of other types of registries

In addition to registries such as EURAP and NAAPR, which have been established specifically for the purpose of assessing the safety of different ASMs during pregnancy, generic administrative healthcare registries have been utilized for similar purposes. Different national health registers from the Nordic countries include data on births, filled prescriptions, and pregnancy outcomes such as malformations in the offspring, and they can be linked for the purpose of assessing associations. The advantages of these registers are that they are nationwide and population-based unlike the specific epilepsy and pregnancy registries that rely on voluntary enrolment of pregnant women. They can also include a comparison group of offspring of healthy mothers and of untreated mothers with epilepsy. Limitations, in comparison with the epilepsy and pregnancy registries, include the lack of reliable information on the mothers’ epilepsy type, no information on seizure control, less detailed information on ASM doses during pregnancy, and possibly also a less meticulous assessment of the offspring.

Nevertheless, these national registries have made important contributions over the years, confirming the increased risk of MCM with exposure to valproate [13, 23] and more recently also with topiramate ([14]; Table 1). In general, the absolute prevalence of MCMs by different ASMs are somewhat lower in these studies compared with the specific epilepsy registries. The fact that the latter include selected patients, possibly with more severe epilepsy and higher ASM doses, and also with a higher vigilance and active search for MCMs, could contribute to the higher reported prevalence.

Limitations of epilepsy and pregnancy registries

The outcome of primary interest in the epilepsy and pregnancy registries is occurrence of MCM. Hence, they are not designed to provide information on the long-term neurodevelopment of the exposed children. For such outcomes, smaller-scale prospective observational studies have been instrumental, demonstrating important dose-dependent adverse effects of valproate exposure during pregnancy on child IQ [24, 25]. But in this regard, the national health registries can also have a role permitting long-term follow-up of exposed children in the various patient registers. Studies based on data from Nordic registries have revealed an increased risk of autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities with exposure to valproate [26, 27] and also with topiramate [27].

Practical conclusion

-

For over 20 years, independent antiepileptic drugs and pregnancy registries have greatly contributed to our understanding of the safety of frequently used ASMs, providing data to facilitate the management of epilepsy in pregnancy.

-

Although complementary information can be obtained from population-based national administrative registers, EURAP and other antiepileptic drugs and pregnancy registries provide the best information on drug doses throughout pregnancy, the women’s types of epilepsy, and their seizure control.

-

So far, the registries have provided meaningful data only for the most frequently used ASMs in monotherapy. Information is still insufficient for many ASMs, especially on recently introduced ASMs and those used in combinations.

-

These registries do not have an end date for completion and closure. Many relevant questions remain unanswered and more will arise with new ASMs. It is thus important that physicians continue to support the registries by reporting pregnancies.

References

Singh A, Trevick S (2016) The epidemiology of global epilepsy. Neurol Clin 34(4):837–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2016.06.015

Meadow SR (1968) Anticonvulsant drugs and congenital abnormalities. Lancet 2(7581):1296. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(68)91781-9

Holmes LB, Harvey EA, Coull BA et al (2001) The teratogenicity of anticonvulsant drugs. N Engl J Med 344(15):1132–1138. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200104123441504

Edey S, Moran N, Nashef L (2014) SUDEP and epilepsy-related mortality in pregnancy. Epilepsia 55(7):e72–e74. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12621

ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies, Tomson T, Battino D, Craig J et al (2010) Pregnancy registries: differences, similarities, and possible harmonization. Epilepsia 51(5):909–915. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02525.x

Cunnington MC, Weil JG, Messenheimer JA et al (2011) Final results from 18 years of the international lamotrigine pregnancy registry. Neurology 76(21):1817–1823. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821ccd18

Scheuerle AE, Holmes LB, Albano JD et al (2019) Levetiracetam pregnancy registry: final results and a review of the impact of registry methodology and definitions on the prevalence of major congenital malformations. Birth Defect Res 111(13):872–887. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdr2.1526

Hernandez-Diaz S, Smith CR, Shen A et al (2012) Comparative safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. Neurology 78:1692–1699

Mawhinney E, Craig J, Morrow J et al (2013) Levetiracetam in pregnancy: results from the UK and Ireland epilepsy and pregnancy registers. Neurology 80:400–405

Campbell E, Kennedy F, Russell A et al (2014) Malformation risks of antiepileptic drug monotherapies in pregnancy: updated results from the UK and Ireland Epilepsy and Pregnancy Registers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 85:1029–1034

Tomson T, Battino D, Perucca E (2019) Teratogenicity of antiepileptic drugs. Curr Opin Neurol 32(2):246–252. https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0000000000000659

EURAP Study Group, Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E et al (2018) Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol 17(6):530–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30107-8

Veiby G, Daltveit AK, Engelsen BA, Gilhus NE (2014) Fetal growth restriction and birth defects with newer and older antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. J Neurol 261:579–588

Cohen JM, Alvestad S, Cesta CE et al (2022) Comparative safety of antiseizure medication monotherapy for major malformations. Ann Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.26561

EURAP study group, Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E et al (2011) Dose-dependent risk of malformations with antiepileptic drugs: an analysis of data from the EURAP epilepsy and pregnancy registry. Lancet Neurol 10(7):609–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70107-7

Eurap Study Group (2009) Utilization of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy: comparative patterns in 38 countries based on data from the EURAP registry. Epilepsia 50(10):2305–2309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02093.x

EURAP Study Group, Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E et al (2019) Declining malformation rates with changed antiepileptic drug prescribing: An observational study. Neurology 93(9):e831–e840. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000008001

EURAP Study Group, Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E et al (2016) Withdrawal of valproic acid treatment during pregnancy and seizure outcome: observations from EURAP. Epilepsia 57(8):e173–e177. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13437

Holmes LB, Mittendorf R, Shen A et al (2011) Fetal effects of anticonvulsant polytherapies: different risks from different drug combinations. Arch Neurol 68(10):1275–1281. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2011.133

EURAP Study Group, Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E et al (2015) Dose-dependent teratogenicity of valproate in mono- and polytherapy: an observational study. Neurology 85(10):866–872. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001772

Eurap Study Group (2006) Seizure control and treatment in pregnancy: observations from the EURAP epilepsy pregnancy registry. Neurology 66:354–360

EURAP Study Group, Battino D, Tomson T, Bonizzoni E et al (2013) Seizure control and treatment changes in pregnancy: observations from the EURAP epilepsy pregnancy registry. Epilepsia 54(9):1621–1627. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12302

Christensen J, Trabjerg BB, Sun Y et al (2021) Prenatal exposure to valproate and risk of congenital malformations-could we have known earlier?—A population-based cohort study. Epilepsia 62(12):2981–2993. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.17085

Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N et al (2013) Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol 12:244–252

Baker GA, Bromley RL, Briggs M et al (2015) IQ at 6 years after in utero exposure to antiepileptic drugs: a controlled cohort study. Neurology 84:382–390

Christensen J, Gronborg TK, Sorensen MJ et al (2013) Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and childhood autism. JAMA 309:1696–1703

Bjørk MH, Zoega H, Leinonen MK et al (2022) Association of prenatal exposure to antiseizure medication with risk of autism and intellectual disability. JAMA Neurol 79(7):672–681. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.1269

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

T. Tomson reports support for EURAP from the following: Angelini, Accord, Bial, EcuPharm, Glenmark, GSK, UCB, Sanofi, Teva, Zentiva, Jazz/GW, SFGroup, and speakers’ honoraria to his institution from Angelini, UCB, GSK and UCB. D. Battino reports no conflicts of interest.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies mentioned were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Additional information

Scan QR code & read article online

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tomson, T., Battino, D. The importance of pregnancy registries for the management of women with epilepsy and childbearing potential: Emphasis on EURAP. Clin Epileptol 36, 192–196 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10309-023-00603-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10309-023-00603-2

Keywords

- Antiseizure medication

- Congenital malformations

- Epileptic seizures

- Abnormalities, drug-induced

- Neurodevelopment