Abstract

Organizations continuously adapt and innovate their business models to remain competitive. To support the management of business models throughout their lifecycle, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) related to business models play an important role. However, the current research on business model KPIs is dispersed and lacks clarity on how they are defined, concretized, and managed throughout their lifecycle. Therefore, we conducted a systematic literature review to analyze and consolidate the current state of the research on KPIs for business models. We identified 35 relevant publications and classified them in a concept matrix consisting of five categories related to business models and KPI management. In addition, we synthesized the business model KPIs referred to in the literature into a catalog structured by business model dimensions. Based on our review and analysis, we formulate avenues for further research on KPIs for business models. Practitioners can use the overview of available approaches for business model KPI management and the catalog of business model KPIs to effectively manage and define KPIs for their organization’s business models.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

To remain competitive in today’s dynamic business environment, organizations focus on continuously innovating and improving their business models (Foss and Saebi 2017; Wirtz and Daiser 2018). A business model describes how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value (Teece 2010). It functions as a useful concept to understand, communicate, and manage an organization’s business logic (Osterwalder et al. 2005). The management of business models is viewed as a continuous cycle, referred to as the business model management lifecycle (Terrenghi et al. 2017; Wirtz 2020; Globocnik et al. 2020). The business model management lifecycle generally consists of five main phases: design, implementation, operation, adaptation and modification, and control (Wirtz 2020). To support decision-makers in effectively managing their organization’s business models throughout their lifecycle, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) play a crucial role.

KPIs are a set of performance indicators (also called performance measures or performance metrics) that capture the most critical performance aspects for an organization’s current and future success (Parmenter 2020). They enable organizations to operationalize their strategic objectives and assess how well they are performing in relation to these objectives (Domínguez et al. 2019). In the context of business model management, KPIs are essential in guiding the development and evaluation of business models across all phases of their lifecycle (Gilsing et al. 2022). In the design phase, organizations use KPIs to formulate measurable objectives for new business models (Heikkilä et al. 2016; Gilsing et al. 2021b). During implementation, the selected KPIs are further concretized to evaluate and track the performance of the new model (di Valentin et al. 2013; Stalmachova et al. 2022). Once the business model is operationalized, organizations use KPIs to control their business model performance and benchmark against competitors to make timely adaptations (Afuah and Tucci 2003).

Several research contributions toward the definition of business model KPIs have been reported in the academic literature. Existing research mainly consists of KPI lists dedicated toward a specific business model type, such as KPIs for networked organizations (Heikkilä et al. 2016) or e-business models (Dubosson-Torbay et al. 2002). Moreover, several methods and frameworks have been put forward to support the definition of KPIs for business models (e.g., Heikkilä et al. 2014; Montemari et al. 2019). Despite these contributions, the existing knowledge on business model KPIs is fragmented. Currently, researchers lack an overview of which business model KPIs are proposed in the academic literature and how existing research supports organizations in systematically managing their business model KPIs. At the same time, practitioners are still facing challenges in identifying relevant KPIs for their organization’s business models (Terrenghi et al. 2017). Without the right KPIs, a gap might occur between the envisioned business model design and its implementation, resulting in many promising business model ideas failing to reach the market (Frankenberger et al. 2013; Geissdoerfer et al. 2017).

To address this research gap, we aimed to analyze and consolidate the current state of the literature on business model KPIs. Accordingly, we formulated the following research question (RQ) to guide our research:

RQ

Which KPIs related to business models are referred to in the academic literature, and how are they managed?

To answer this question, we conducted a systematic literature review to identify existing studies on business model KPIs. We iteratively classified the existing works in a concept matrix to analyze how they contribute to the management of business model KPIs and to identify key shortcomings in the literature. Moreover, we extracted the business model KPIs mentioned in the selected studies and synthesized them into a catalog structured by business model dimensions.

Our review contributes to business model research by providing a structured overview and critical assessment of the research on business model KPIs. Thereby our research responds to the multiple calls in the literature for investigating KPIs for business models and how they can be managed (Burkhart et al. 2011; Lambert and Montemari 2017; Nielsen et al. 2018). Based on our review and synthesis of the literature, we formulated avenues for further research on business model KPIs and their respective management. We contribute to practice by providing an overview of available approaches for business model KPI management that organizations can adopt to effectively manage their business models across all phases of their lifecycle. Furthermore, organizations can use the KPI catalog to identify and define KPIs for their business models. The catalog provides a comprehensive categorization of business model KPIs that can be tailored to the specific context and needs of the organization.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the background on the key concepts of business model, KPI management, and KPI-based business model evaluation. Next, Sect. 3 describes our research approach and the development of the concept matrix and catalog of KPIs. We present the results of our review and analysis in Sect. 4. In Sect. 5, we discuss the results and outline opportunities for future research. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes our review and discusses its limitations.

2 Background

2.1 The business model concept

In the last two decades, the business model concept has gained importance in several research domains, including information systems (IS), strategic management, and technology and innovation management (Zott et al. 2011; Wirtz et al. 2016; Massa et al. 2017), and more recently, in environmental sustainability and social entrepreneurship (Evans et al. 2017; Geissdoerfer et al. 2018; Pedersen et al. 2021). Over the years, researchers have proposed several business model definitions and interpretations of the concept (Al-Debei and Avison 2010; Zott et al. 2011; Massa et al. 2017). For example, according to Magretta (2002), a business model can be described by a story that explains how an organization operates. According to Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010), business models are made up of strategic choices and the consequences of these choices, and as such, they reflect an organization’s realized strategy. Other researchers have investigated business models as activity systems (Zott and Amit 2010), models (Baden-Fuller and Morgan 2010), and configurational patterns for addressing reoccurring business problems (Gassmann et al. 2014; Taran et al. 2016).

Despite this vast amount of research, researchers have not yet reached an agreement about the definition of a business model (Zott et al. 2011; Foss and Saebi 2018). Nevertheless, according to Foss and Saebi (2017), most definitions in the current literature are consistent with Teece (2010), who defines a business model as “the design or architecture of the value creation, delivery, and capture mechanisms” of an organization (Teece 2010, p. 172). We follow this convergence and adopt Teece’s (2010) definition in this study. A well-designed business model describes what value proposition the organization offers, who the target customer is, what capabilities are needed to support this, and what costs and benefits are associated with this (Gassmann et al. 2014; Turetken et al. 2019).

From an IS perspective, a business model functions as an intermediate conceptual layer between an organization’s business strategy and business processes, including its information technology (IT) systems (Al-Debei and Avison 2010; Veit et al. 2014). One of the main differences between these organizational layers is the nature of the information that each concept provides (Al-Debei and Avison 2010). While a business strategy provides a set of high-level choices of how an organization will compete in a particular industry, the business model depicts the organization’s tactical choices about how it creates value for its customers and captures value from this (Magretta 2002; Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010). In contrast, business processes provide a more detailed description of how an organization’s operations are executed (Gordijn et al. 2000; Turetken et al. 2019). Consequently, the business model has emerged as a distinct unit of analysis and innovation (Zott and Amit 2013; Saebi et al. 2017) that exceeds the scope of other concepts, such as products, services, and business processes (Bucherer et al. 2012; Frankenberger et al. 2013; Lara Machado et al. 2022).

To support the management of business models throughout their lifecycle, several frameworks, methods, and software tools have been put forward in the literature (Bouwman et al. 2012; Schwarz and Legner 2020). The most influential business model framework in both research and practice is the Business Model Canvas (BMC) by Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010). Originally based on the Business Model Ontology (BMO) (Osterwalder 2004), the BMC consists of nine building blocks of business models, namely value propositions, customer segments, customer relationships, channels, key partners, key activities, key resources, cost structure, and revenue streams (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010). It poses as the quasi-standard for analyzing and communicating business models (Massa et al. 2017; Foss and Saebi 2018). Other frequently used business model frameworks and conceptualizations include the unified business model framework (Al-Debei and Avison 2010), STOF model (Bouwman et al. 2008), and Business Model Navigator (Gassmann et al. 2014). These business model tools function as boundary objects that facilitate collaboration and communication about business models between stakeholders (Schwarz and Legner 2020).

In practice, most organizations adopt more than one business model targeting different customer segments or industries (Schwarz et al. 2017). For example, Mercedes-Benz decided to partner up with BMW to complement its traditional car manufacturing business model with a car-sharing business model under the brand "Share Now”(ShareNow 2022). As business models can be vastly different in terms of their target customers, value offerings, and the required resources and activities to realize them, different business models will have different business model KPIs (Heikkilä et al. 2016; Gilsing et al. 2021b). For instance, KPIs relevant for the business model of consumer bank in digital transformation (Stalmachova et al. 2022) will be very different from the KPIs of a smart city business model (Díaz-Díaz et al. 2017).

2.2 Managing key performance indicators

Organizations need to evaluate their activities and systems to determine the extent to which their objectives are being fulfilled. Therefore, they carry out performance measurement activities, for which they make use of metrics known as Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) (Domínguez et al. 2019). KPIs are defined as “those indicators that focus on the aspects of organizational performance that are the most critical for the current and future success of the organization” (Parmenter 2020, p. 6). KPIs are used to measure the impact of change and, thus, are distinct from other performance concepts such as “evaluation criteria” (used to assess whether or not performance has changed) and “success factors” (used to explain the drivers behind performance) (Parmenter 2020). Using KPIs for performance measurement is the most common approach used in practice, surpassing other methods and tools such as performance appraisals, mission and vision statements, and Lean/Six Sigma management, as shown by a global survey by the Advanced Performance Institute (Marr 2012).

KPIs are used to measure performance at different organizational levels. While KPIs at the strategic level are often driven by external stakeholder perspectives, managers at the tactical level (i.e., the level of the business model) use KPIs to allocate resources and evaluate business performance against strategic objectives (Chennell et al. 2000; Gunasekaran et al. 2004). At the operational level, operational performance indicators and metrics are used to evaluate the business processes that support delivering products and services to the customer (Del-Río-Ortega et al. 2013; Van Looy and Shafagatova 2016). While the use of KPIs for measuring business process performance is a well-established concept in research and practice (e.g., Wieland et al. 2015; Van Looy and Shafagatova 2016), little attention has been paid to identifying KPIs relevant to measuring and managing the performance of business models (Nielsen et al. 2018).

Typically, the identification and analysis of relevant KPIs are part of the performance measurement activities suggested by performance measurement methods and frameworks (Nudurupati et al. 2011). These tools help organizations plan and conduct performance measurement activities in many different fields, including strategic management (Kaplan and Norton 1996), business process management (Leyer et al. 2015), enterprise architecture (Schelp and Stutz 2007), and supply chain management (Gunasekaran et al. 2004). One of the most well-known performance measurement frameworks is the Balanced Scorecard (BSC), developed by Kaplan and Norton (1992, 1996). The BSC is used for translating an organization’s strategic objectives into measurable outcomes based on four dimensions of organizational performance: financial, customer, internal business processes, and learning and growth. It is the most frequently used performance measurement framework in both research and practice (Neely et al. 2005; Bain & Company 2018). Other frequently discussed methods and frameworks in the literature include the Performance Pyramid (Cross and Lynch 1988), Performance Measurement Matrix (Keegan et al. 1989), Goal Question Metric approach (Basili et al. 1994), and Performance Prism (Neely et al. 2001).

Business model performance is distinct from firm performance. As in the example of the automotive company Mercedes-Benz, customer satisfaction can be measured as an organizational KPI to evaluate the overall strategy and performance of the firm (Williams and Naumann 2011). However, since Mercedes-Benz is running multiple business models in parallel (i.e., a manufacturing and a car-sharing business model), the organization would also want to measure customer satisfaction separately in different ways for its distinct business models targeted at different customer segments, to manage how they perform. In addition, different business models require different business model KPIs. For instance, the value proposition that Mercedes-Benz offers in its manufacturing business model is different than the value proposition of its car-sharing business model. These two different business models also have a unique revenue model and specific business processes and activities to support it. As such, Mercedes-Benz would want to specify different KPIs for each business model to manage their performance.

2.3 Business model evaluation and key performance indicators

In recent years, there has been a rise in the number of publications related to business model evaluation (Budler et al. 2021; Gilsing et al. 2022). Evaluation of business models takes place during the different phases of the business model management lifecycle. During the early phases (e.g., design), evaluation activities are performed to assess different business model design alternatives and support design decisions (Mateu and Escribá-Esteve 2019; Gilsing et al. 2021a). Subsequently, in later phases of the lifecycle (i.e., during implementation and operation), business model evaluation aids in monitoring operational performance and mitigating risks and uncertainty regarding the newly implemented business model (di Valentin et al. 2013; Terrenghi et al. 2017).

Several approaches for business model evaluation are presented in the literature (Tesch and Brillinger 2017; Gilsing et al. 2022). Evaluation approaches used prior to the implementation of a business model include the assessment of different alternative business model designs and trial-and-error-based testing and prototyping, which are often of qualitative nature (Tesch and Brillinger 2017). Examples of such approaches include SWOT analysis (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010), external driver analysis (de Reuver et al. 2009), and business model roadmapping (de Reuver et al. 2013). As the business model progresses toward implementation and operation, data and information about the business model and its performance become increasingly available and accurate (Gilsing et al. 2021b). Therefore, evaluation approaches used during and after business model implementation often rely on quantitative data and include financial spreadsheets (Gordijn and Akkermans 2001; Daas et al. 2013), decision support systems (di Valentin et al. 2013; Dellermann et al. 2019), and simulation analysis using System Dynamics (Cosenz and Noto 2018; Moellers et al. 2019).

One possible way to evaluate business models is by using KPIs (Heikkilä et al. 2016; Gilsing et al. 2021b). Business model KPIs are used and managed in various ways and are used before, during, and after business model implementation. Before business model implementation, organizations use KPIs to formulate measurable objectives for the expected performance of a newly designed business model (Heikkilä et al. 2014; Montemari et al. 2019; Gilsing et al. 2021b). For example, organizations may be interested in measuring the satisfaction of customer needs, which is an important indicator of business model performance (Wirtz 2020). During and after business model implementation, KPIs are used to monitor and control a business model’s performance, to make timely improvements and adaptations when the model’s performance deflects from its expected performance (di Valentin et al. 2013; Globocnik et al. 2020). Once the business model is implemented and operational, KPIs provide a way to compare alternative business models and benchmark an organization’s business model against those of competitors (Afuah and Tucci 2003; Díaz-Díaz et al. 2017).

In sum, we argue that KPIs are instrumental for business model evaluation, as they can be used to measure, monitor, and compare the performance of business models throughout their lifecycle.

3 Research approach

The objective of our research is to analyze and consolidate the current state of the literature on business model KPIs. To this end, we conducted a systematic literature review. A systematic literature review is a structured and reproducible method to identify, evaluate, and synthesize the existing body of knowledge (Kitchenham and Charters 2007; Snyder 2019) and to provide a foundation for future research on a particular topic of interest (Webster and Watson 2002). In IS research on business models, systematic literature reviews have been conducted to investigate methods for evaluating business models (Gilsing et al. 2022), dependencies among business model dimensions (Vorbohle et al. 2021), and characteristics of business model portfolios (Schwarz et al. 2017). In this study, we use a systematic literature review to assess existing research on KPIs for business models and to synthesize the KPIs mentioned in existing research into a catalog.

Scholars have proposed various guidelines and approaches for conducting systematic literature reviews in IS research (Vom Brocke et al. 2015). While most approaches offer general guidelines for conducting the review, different studies have different emphases. For example, Levy and Ellis (2006) recommend that researchers build on reputable and peer-reviewed IS journals and conference outlets. Vom Brocke et al. (2009) and Bandara et al. (2011) emphasize the need to rigorously document the literature search process. Other approaches include guidelines for synthesizing and presenting the findings of a literature review in a structured way (Webster and Watson 2002).

In this study, we adopt the guidelines for conducting a standalone systematic literature review by Okoli (2015), because it provides a standardized process with step-by-step guidelines. It is especially suitable for studies in which multiple researchers are involved. Accordingly, our research process comprises four main phases: planning, selection, extraction, and execution (Okoli 2015). The following subsections describe the literature search and selection process (Sect. 3.1), the development of a concept matrix based on the analysis of the selected studies (Sect. 3.2), and the coding and synthesis of the identified business model KPIs in a structured catalog (Sect. 3.3).

3.1 Systematic literature review process

During the planning phase, we identified the purpose of our literature review and drafted the review protocol. The purpose of our review is to analyze the current state of research on KPIs for business models. Based on our review and analysis, we aim to identify the gaps and develop recommendations for future research. Our review is aimed at researchers who study business models and practitioners who are designing and implementing an organization’s business model. Subsequently, we established a review protocol that all authors followed to discover and examine relevant studies, which we describe in more detail below.

In the selection phase, we first conducted pilot searches in the academic library Scopus using different combinations of keywords. Based on this initial search, we specified the following search string: “business model*” AND (“performance indicator*” OR “performance measure*” OR “performance metric*” OR “KPI*”). We included the terms (key) performance indicator, performance measure, and performance metric in our search string since these terms are often used interchangeably in the literature (Lebas and Euske 2007). In this paper, we adopt the term “KPI”, as managers in practice mostly use this term to refer to a carefully selected set of performance indicators with a specific purpose in mind (Hope 2007). After determining the search string, we defined several criteria for including or excluding publications during our review. We decided to include only studies that (1) adopt a definition of business models that is in line with our interpretation of the concept as outlined in Sect. 1, (2) present clearly defined business model KPIs or approaches for business model KPI management, performance indicators, measures, or metrics, (3) are published in academic venues, such as journals, conference proceedings, or academic book chapters (and excluded those that are published as workshop proceedings, book editorials, and case study descriptions), and (4) are written in English. Subsequently, we selected the digital libraries Scopus, Web of Science, and AISeL to identify relevant studies, as their combination covers the venues that are most relevant to the objective of our study (Bandara et al. 2011). We conducted a title, abstract, and keyword search within these libraries using the specified search string, which resulted in an initial set of 879 studies (as of 25 April 2022).

Figure 1 provides an overview of the process we followed in the extraction phase, where we systematically extracted relevant information from selected papers. As some studies were present in more than one of the selected libraries, we first eliminated 236 duplicate studies. Next, we screened the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the remaining 589 studies based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria. To increase the reliability of our research, two authors of this paper evaluated the relevance of each study. The screening of the title, abstract, and keywords resulted in an exclusion of 423 studies. The two authors independently reviewed the full text of the remaining 220 studies. Any conflict of thought on why a publication should be included or excluded was discussed by the authors until an agreement was reached. We excluded publications that did not fit the scope of our study; for instance, publications that investigate the effect of business models on firm performance (Andries and Debackere 2007; König et al. 2019; Haddad et al. 2020) or publications that do not clearly relate the presented KPIs to business models (Guah and Currie 2004; Dangayach et al. 2020; Cavicchi and Vagnoni 2022). Moreover, we found that some authors published multiple studies on developing a single approach (e.g., Wilbik et al. 2020; Gilsing et al. 2021b). In these cases, we selected the most comprehensive study.

Based on the full-text review, we selected 20 studies that we deemed relevant for the scope of our review and that met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Next, we performed a structured snowballing procedure (Wohlin 2014) to discover related works on business model KPIs and KPI management. The snowballing procedure started with the initial set of 20 studies resulting from our search and review of the literature in the selected databases. First, we performed a backward snowballing search by identifying and scanning the publications referenced by the studies in our initial set. To include or exclude new publications, we applied the same criteria as specified in the selection phase of our review. Second, we performed a forward snowballing search on the initial set of studies using the ‘cited by’ feature in Google Scholar, as suggested by Wohlin (2014). We scanned the titles of the citing publications to decide about their relevancy and scanned the abstracts and full texts if we considered the publication potentially relevant. If a new study was included in our sample, we also analyzed its references and the publications it was cited by to discover additional relevant works. We continued these iterations of snowballing back and forth until no new relevant publications were found (Wohlin 2014). The snowballing procedure resulted in the discovery of an additional 15 relevant publications, leading to a final set of 35 selected studies.

Finally, in the execution phase of our literature review, we analyzed and synthesized the findings from the selected papers. To investigate how existing research supports the management of business model KPIs, we analyzed the final set of 35 studies following a concept-centric approach through a concept matrix (Webster and Watson 2002). We describe the development process of the concept matrix in Sect. 3.2. To identify which business model KPIs are referred to in the academic literature, we aimed to extract KPIs related to business models from the selected studies and synthesize them into a catalog of business model KPIs. The iterative coding and synthesis process is described in Sect. 3.3.

3.2 Development of the concept matrix

The categories in the concept matrix and their respective concepts were derived based on the theoretical works on business models and KPI management. They were refined through an iterative process of analyzing the selected studies. The goal of developing a concept matrix is to provide an overview of the existing literature and identify knowledge gaps that can pose opportunities for further research (Vom Brocke et al. 2009).

We derived the following categories from the literature (Fig. 2): the type of approach, the support offered during different KPI management lifecycle phases, the stage at which the KPIs are used, the KPI type, and the context for which the approach is designed. In the following, we describe each category and its related concepts in more detail.

The approaches defined in the identified papers can be considered as design artefacts (Hevner et al. 2004). Accordingly, artefacts can be in the form of a construct (vocabulary, symbols), model (abstractions, representations), method (practices), and instantiation (implementations, prototype systems). In the context of our research, constructs are not a relevant form of approach regarding the management of KPIs. Moreover, we consider KPIs, catalogs of KPIs, and frameworks as types of models, because they provide representations and abstractions (Hevner et al. 2004) that support decision-making about business model KPIs. We interpret KPIs as a central aspect of performance to an organization’s current and future success (Parmenter 2020). While some studies give examples of one or multiple KPIs, others systematically propose catalogs of KPIs. The catalogs presented in the literature are lists or repositories of multiple business model KPIs that are structured based on a set of specific elements, such as business model dimensions (Dubosson-Torbay et al. 2002; Heikkilä et al. 2016) or value chain activities (di Valentin et al. 2012b). Furthermore, several studies have developed a framework from which business model KPIs can be derived. In light of our research, we view frameworks as meta-models (Peffers et al. 2012) that provide a conceptual structure intended to support or guide business model KPI management. Furthermore, we consider methods to be a set of practical guidelines structured in a systematic way (Brinkkemper 1996) that aids in managing business model KPIs. Finally, we view instantiations as the conceptual structure or implementation of models and methods in (part of) a software system (Hevner et al. 2004) that is dedicated to business model KPI management.

The existing approaches provide support during the different phases of the KPI management lifecycle. Based on KPI lifecycles and performance measurement phases mentioned in the existing business model literature (Heikkilä et al. 2014; Mourtzis et al. 2018; Montemari et al. 2019), and inspired by the business process KPI lifecycle by Del-Río-Ortega and Resinas (2009) and the KPI management taxonomy by Domínguez et al. (2019), we uncovered five generic phases in the lifecycle of business model KPI management: definition, selection, operationalization, measurement, and reporting. During the definition phase, KPIs are identified and defined to measure the performance of a particular business model. The selection phase involves picking a set of relevant KPIs based on the organization’s strategic objectives. Subsequently, the selected KPIs are gradually concretized during the operationalization phase. In the measurement phase, the values of the concretized KPIs are calculated. To calculate the KPI values, performance data and information about the business model need to be gathered. Lastly, in the reporting phase, the measured KPI values are summarized into a comprehensive report or dashboard, which the responsible decision-maker can monitor.

KPIs are used in two stages: ex-ante realization and ex-post realization. The use of KPIs in ex-ante realization implies that the KPIs are defined and evaluated during the analysis and design phase of a new business model, before the new model is implemented (Heikkilä et al. 2014; Gilsing et al. 2021a). In the early phases of business model management, KPIs and their associated values often take the form of qualitative statements based on the intentions and expectations of the focal organization’s management (Gilsing et al. 2020). These qualitative KPIs are then concretized when the newly designed business model is implemented (Heikkilä et al. 2016). Subsequently, KPIs are used in ex-post realization to monitor and control the performance of the new model based on the concrete KPIs and their expected values (Wirtz et al. 2016; Terrenghi et al. 2017).

We identify two types of KPIs: quantitative and qualitative (Domínguez et al. 2019). Qualitative KPIs are metrics that are not directly measurable (Popova and Sharpanskykh 2010). Examples of such KPIs in the business model context include customer satisfaction, brand image, and service quality (Heikkilä et al. 2016). Qualitative KPIs can be measured by aggregating other metrics or by, for example, conducting survey data analysis (Domínguez et al. 2019). On the other hand, quantitative KPIs are hard performance indicators that are directly measurable (Popova and Sharpanskykh 2010). For business models, examples of quantitative KPIs include the number of unique visitors, number of customer complaints, time to market (in days), and average order size (Heikkilä et al. 2016). If a study provides an approach or KPI of the quantitative type, we classify it as quantitative, and the other way around for qualitative. When publications provide approaches or KPIs for both qualitative and quantitative KPIs, we classify them into both categories.

The context of the approach describes the hierarchical level of the business model for which the approach is designed. Following Osterwalder et al. (2005), we make a distinction between two hierarchical conceptual levels of the business model: (1) approaches that are focused on managing KPIs for a specific type of business model, such as start-ups and governmental organizations, and (2) approaches that are focused on KPIs and their management for business models in general.

3.3 Development of the catalog of business model key performance indicators

To identify KPIs related to business models, we screened the selected sample of studies resulting from the systematic literature review (Sect. 3.1). We performed several coding iterations to synthesize the extracted KPIs from the selected studies into a catalog. Figure 3 shows the catalog development process.

In the first iteration, two authors iteratively screened and coded the KPIs presented in each publication. We found that 31 of the 35 publications in the sample contained some type of KPIs related to business models. In total, we extracted an unstructured set of 951 KPIs from the sample, including duplicates. In this phase, we also kept track of how the KPIs were operationalized, for example, through a qualitative question or mathematical formula. The qualitative questions are expected to be answered by managers in a subjective way to provide an indication of a given performance aspect. On the other hand, mathematical formulas are used to calculate KPIs in an objective way based on quantitative data. We must, however, note that 16 of the 31 selected studies did not provide a concrete operationalization for the presented KPIs.

In the second iteration, we defined the initial conceptual dimensions of the catalog. We selected the nine building blocks of the Business Model Canvas (BMC) (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010) as initial dimensions of the catalog: value propositions, customer relationships, customer segments, channels, key activities, key resources, key partners, revenues streams, and cost structure. We chose the BMC because it is the most widely used framework to represent business models in research and practice (Massa et al. 2017) and because it is a general framework that is not specific to a particular business model context. We favored the BMC over other performance measurement frameworks, such as the Balanced Scorecard (BSC), because it is typically used to evaluate business model performance (e.g., Montemari et al. 2019; Minatogawa et al. 2019; Stalmachova et al. 2022). Thus, in the context of performance measurement, business model dimensions can be used to guide the identification of KPIs that can be measured and compared (Osterwalder et al. 2005; Batocchio et al. 2017).

In addition, we adopted the term ‘business model pillar’ (Osterwalder et al. 2005) to describe the meta-dimensions of the catalog. Accordingly, we categorized the initial nine BMC dimensions into the business model pillars ‘Frontstage’, ‘Backstage’, and ‘Profit Formula’ (Osterwalder et al. 2020). The Frontstage pillar includes KPIs related to the value propositions, customer relationships, customer segments, and channels. The KPIs categorized in the Backstage pillar are concerned with the performance of the business model’s key activities, key resources, and key partners. The third pillar, Profit formula, contains KPIs related to the value capture mechanism of the business model and, thus, includes the revenue stream and cost structure dimensions.

Next, we inductively coded and classified the identified business model KPIs according to the nine dimensions of the BMC. In this phase, we combined similar indicators and rephrased their names into more general terms. For instance, we merged the identified KPIs ‘(Customer) value’ (Afuah and Tucci 2003) and ‘Extent to which the business model is valuable’ (Heikkilä et al. 2016) into the more general KPI ‘Perceived customer benefit’. Moreover, during this iterative process of categorization and synthesis, we discovered that several KPIs presented in the literature were related to profitability, which relates to both the revenue streams and cost structure of business models (Osterwalder 2004). Therefore, we added the new dimension ‘Profitability’ to the Profit Formula pillar to account for profit-related KPIs mentioned in the literature. We added the ‘Context’ pillar to categorize KPIs related to a business model’s ‘contextual logic’ (Lüdeke-Freund et al. 2017), which refers to the broader stakeholder environment in which the business model is embedded. We identified two subcategories of KPIs related to the Context pillar of business models: a market subcategory and a sustainability and society subcategory. The market subcategory includes KPIs related to the market that the business model operates in, such as indicators related to shareholder expectations. The sustainability and society subcategory is concerned with KPIs related to non-economic costs and benefits for the environment and society in which the business model is embedded.

Lastly, we adapted and refined the operationalizations of the KPIs in this phase. If the original authors of a publication provided a suitable description of the operationalization of a KPI, we adopted that description in our catalog. When an operationalization depicted by the original authors did not provide sufficient detail, we discussed and improved it. We tried to define the operationalizations as close as possible to their original definition and context by providing additional insight into how they could be defined. If the operationalization of a KPI was missing, we looked for appropriate definitions in the literature and discussed them to reach a consensus.

After reaching an agreement about the initial catalog, our third and final iteration consisted of reordering and refining it until all authors agreed on its final form. To ensure the robustness and comprehensiveness of the catalog, the authors met multiple times to align on the tentative syntheses and categorization of the KPIs. Therefore, the catalog of business model KPIs resulting from the iterative coding process was subsequently validated through triangulation (Cresswell 1998) between the authors.

4 Results

In the following subsections, first, we discuss the distribution of publications resulting from our literature review in terms of their publication year, type of study, and citation network. Next, we present the concept matrix that was filled in based on the results of the review. Lastly, we describe the catalog of business model KPIs.

4.1 Distribution of publications

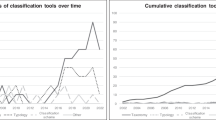

Figure 4 shows the chronological distribution of publications per year (from 2001 to 2022) and publication type (journal articles, conference papers, and book chapters). The distribution over the years shows that since 2016, more studies on business model KPIs have been published, with the highest number of publications in 2017. Concerning the type of publications, the majority of studies are published in journal articles (N = 16), followed by papers in conference proceedings (N = 15) and book chapters (N = 4). The statistics indicate that before the year 2001, no relevant studies were published. In the initial years, between 2001 and 2007, mainly scholars from the domain of information systems contributed to the number of publications on business model KPIs (e.g., Dubosson-Torbay et al. 2002; Bouwman 2003; Bouwman and van den Ham 2004). In the last five years (2017–2022), the diversity of the contributing domains has increased, with contributions by scholars from the domains of strategic management (e.g., Johnson et al. 2008; Wirtz 2020), technology and innovation management (e.g., Díaz-Díaz et al. 2017; Udo and Ishino 2021), and environmental sustainability (e.g., Morioka et al. 2016; Lüdeke-Freund et al. 2017). This diversity of contributing domains might be explained by the fact that business model research has become increasingly popular over the past two decades (Wirtz et al. 2016; Foss and Saebi 2017), and in particular by the increasing attention devoted to the topic of business model evaluation since 2016 (Budler et al. 2021).

We performed a citation network analysis on the selected publications. This analysis helps to understand the extent to which various authors are aware of one another (Jo et al. 2009). A visualization of the citation network of the included publications is shown in Fig. 5. The nodes in the figure represent the selected publications, and the arrows in between the nodes indicate a citation relationship. As can be seen in the figure, 27 of the 35 selected publications are cited by one or more other publications in the network. The book titled Internet Business Models and Strategies by Afuah and Tucci (2003) is cited the most among the selected publications, with 13 citations in total. The second most cited publication is the journal article by Osterwalder et al. (2005), published in the Communications of the Association for Information Systems (CAIS), with 9 citations from the network. The latter publication is considered a seminal work in business model research (Wirtz et al. 2016; Massa et al. 2017) and includes the proposition that “understanding a company’s business model facilitates the identification of the indicators to follow in an executive management system” (Osterwalder et al. 2005, p. 21). The journal article by Heikkilä et al. (2016), published in Information Systems and e-Business Management (ISeB), has the highest number of references to other publications in the network, with a total of 9 citations to other studies. Furthermore, eight publications do not have any citations to or from other studies in the network. These publications primarily focus on a specific type of business models, such as business models for human resource management (Khoshalhan and Kaldi 2007), healthcare (Kriegel et al. 2016), or product-service systems (Kastalli et al. 2013; Mourtzis et al. 2018). These publications might therefore be less embedded in conventional business model research streams in the domains of information systems, strategy, and innovation management (Zott et al. 2011; Wirtz et al. 2016). Overall, the network analysis indicates a tight connection among the selected publications. From the citation network analysis, it is clear that an initial knowledge base on KPIs for business models was established in the early 2000s by the publications of Afuah and Tucci (2003) and Osterwalder et al. (2005). Other research streams on business model KPIs have evolved around studies on performance management of network-based business models by Heikkilä et al. (2014) and the book on business model management by Wirtz (2020). A more recent line of research by Nielsen et al. (2017) and Montemari et al. (2019) focuses on demonstrating and describing how the business model concept can be used as a starting point for identifying relevant KPIs that can be used for analysis, benchmarking, and performance management for business models.

4.2 Categorization according to concept matrix

Table 1 provides an overview of the selected 35 publications that we included in our literature review and how they are categorized according to the categories of the concept matrix; i.e., type of approach, the support offered in the KPI management lifecycle, the stage at which the KPIs are used for evaluation, KPI type, and context of the approach. We position the identified studies in the left column of the matrix and the relevant categories and their corresponding concepts in the remaining columns. In the following subsections, we synthesize and discuss the extant research based on the categories in the concept matrix.

4.2.1 Type of approach

We make a distinction between different types of approaches for business model KPI management: Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), catalogs of KPIs, frameworks (all three of which we classify as models), methods, and instantiations.

We discovered various Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for business models presented in the literature. Examples of KPIs related to business models include customer satisfaction, average delivery time, service availability, number of partners, R&D expenses, and profit margin (Heikkilä et al. 2016; Montemari et al. 2019). Existing studies mainly focus on defining KPIs for a specific context, such as e-business (Dubosson-Torbay et al. 2002; Afuah and Tucci 2003; Yu 2006) or networked business models (Heikkilä et al. 2014, 2016; Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al. 2015), rather than developing generic KPIs for any type of business model. Furthermore, many researchers consider KPIs related to financial aspects to be important indicators of business model performance, such as operational costs, revenue growth, and profit margin (Afuah and Tucci 2003; Kijl and Boersma 2010; Wirtz 2020). Additionally, we observe an increasing interest in defining and measuring non-financial costs and benefits of business models, such as the impact on environmental sustainability and societal benefits (Lüdeke-Freund et al. 2017; Turetken et al. 2019). Section 4.3 provides a more in-depth analysis of the number and types of business model KPIs presented in the literature.

To introduce business model KPIs in a structured way, researchers often present them in the form of a catalog (e.g., Dubosson-Torbay et al. 2002; Kriegel et al. 2016; Heikkilä et al. 2016). To come up with the set of KPIs in the catalog, researchers carry out literature reviews (Heikkilä et al. 2016), expert interviews (di Valentin et al. 2012b), or a combination of both (Kriegel et al. 2016). Two studies also propose digitizing their catalogs in a software-based database (Nielsen et al. 2017; Mourtzis et al. 2018). One study that stands out is the work by Heikkilä et al. (2016), which features an extensive KPI catalog for networked enterprises developed based on the business model and performance measurement literature. The catalog is structured using the elements of the CSOFT business model ontology (Heikkilä et al. 2010): Customer, Service, Technical, Organizational, and Financial, and extended with three additional perspectives specific to networked organizations (Solaimani and Bouwman 2012): Value Exchange, Information exchange, and Process alignment.

Regarding studies that develop frameworks, we found that current research often builds on existing frameworks for developing new ones. We identified nine studies that designed a new framework based on Kaplan and Norton’s (1992, 1996) Balanced Scorecard (BSC) (e.g., Lüdeke-Freund et al. 2017; Yu 2006, 2014). Moreover, 19 studies mentioned or referred to the BSC, which confirms that it is still a prominent framework for managing KPIs, as indicated in Sect. 2.2. Furthermore, 13 publications used the Business Model Canvas (BMC) (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010) or Business Model Ontology (BMO) (Osterwalder 2004) as a basis for developing a framework for KPI management (e.g., Díaz-Díaz et al. 2017; Minatogawa et al. 2019; Stalmachova et al. 2022). This finding is in line with the proposition of the original authors of the BMC, who argue that understanding an organization’s business model makes it easier to identify KPIs (Osterwalder et al. 2005). Other frequently used or cited frameworks in the business model KPI management literature include the CSOFT ontology (Customer-Service-Organization-Finance-Technology) (Heikkilä et al. 2010) and the Performance Prism (Neely et al. 2001).

Compared to the number of models presented in the literature, extant research has paid less attention to developing methods for supporting business model KPI management. Our literature review revealed that there are different ways of applying these methods, for example for analyzing the performance of an existing business model (e.g., Afuah and Tucci 2003), defining KPIs during the early phases of the business model management lifecycle (e.g., Gilsing et al. 2021b), specifying the causal relationships between KPIs (e.g., Minatogawa et al. 2019), and supporting KPI selection (e.g., Mourtzis et al. 2018). Several authors divide their method into steps, with explicit guidelines for the activities to carry out in each step (Heikkilä et al. 2014; Batocchio et al. 2017; Montemari et al. 2019). Moreover, most authors demonstrate their proposed method through an application in one or multiple case studies (e.g., Afuah and Tucci 2003; Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al. 2015; Minatogawa et al. 2019). Furthermore, methods presented in the literature are often catered toward a specific business model context, such as start-ups (Batocchio et al. 2017), smart cities (Díaz-Díaz et al. 2017), or sustainable business models (Lüdeke-Freund et al. 2017; Minatogawa et al. 2019). In addition, a few authors propose methods that support the design of performance measurement systems based on business models (Heikkilä et al. 2010, 2014; Montemari et al. 2019). For instance, Montemari et al. (2019) propose a process that leads from a business model design to the definition of KPIs. The process starts with identifying business model configurations, then identifying relevant value drivers, and ends with defining KPIs to measure the business model’s value drivers. This method provides guidance for both defining KPIs for a certain business model and for analyzing its performance.

We found six studies that developed instantiations to support business model KPI management. A prominent example is the software instantiation developed by Mourtzis et al. (2018), which comprises an integrated software-enabled tool for selecting and assessing KPIs of product-service system (PSS) business models. PSS is a specific business model in which tangible products are combined with intangible services in a single system (Goedkoop et al. 1999). The tool also supports decision-makers in collecting, storing, processing, and visualizing PSS KPIs. Moreover, we identified three studies that present software instantiations to support the monitoring of business model dynamics and the transformation from an existing business model to a new one (di Valentin et al. 2013; Augenstein and Fleig 2018; Schaffer et al. 2020). In these instantiations, data is extracted from an organization’s ERP system and databases, and the changes in business model KPIs are measured and visualized in a dashboard.

4.2.2 Support during KPI management lifecycle phases

Figure 6 provides an overview of the approaches that support decision-making in each phase of the business model KPI management lifecycle (see Sect. 3.2) that we identified in the existing literature. This subsection presents and discusses the identified approaches per lifecycle phase.

All studies in our sample support the definition of business model KPIs. For this phase, we identified four types of approaches in the literature. The most common approach in existing research aims to support the KPI definition by providing a catalog or list of KPIs relevant to business models (Johnson et al. 2008; Kriegel et al. 2016; Heikkilä et al. 2016). The second most used approach is the development of performance measurement frameworks that support the KPI definition. Instead of offering a list of pre-defined KPIs, these studies allow decision-makers to specify KPIs based on the framework’s measurement areas and high-level indicators (Bouwman and van den Ham 2004; Yu 2006; Lüdeke-Freund et al. 2017). Moreover, two studies propose to specify KPIs based on the performance drivers of the organization that are linked to specific configurations of business model elements (Nielsen et al. 2017; Montemari et al. 2019). Lastly, Gilsing et al. (2021b) propose a set of protoforms (i.e., descriptive suggestions) to support the KPI definition for the different actor roles present in service-dominant business models, such as the customer, orchestrator, or other parties in the business network.

While existing research provides various models and methods for KPI definition, we identified only 11 approaches for selecting KPIs. In this phase, the ‘right’ KPIs are selected that best fit with the considered business model and the preferences of the organization. Most studies discussing KPI selection point out that the indicators should be aligned with the organization’s strategic objectives (Heikkilä et al. 2014; Batocchio et al. 2017) and their corresponding performance drivers (Montemari et al. 2019) or critical success factors (Heikkilä et al. 2014). In addition, many authors stress the importance of balancing between financial and non-financial indicators (e.g., Bouwman and van den Ham 2004; Nielsen et al. 2017). Thus, when selecting KPIs for a certain business model, not only KPIs related to value capture should be considered, but also KPIs relevant to value creation and value delivery should be taken into account. These principles are similar to how the BSC is used to determine a balanced set of performance indicators based on the organization’s strategy (Kaplan and Norton 1996). In most of the studies on KPI selection, researchers propose to select KPIs based on discussions with managers of the focal organization responsible for managing the business model (Heikkilä et al. 2016; Batocchio et al. 2017). We identified three studies that propose software-enabled algorithms for selecting relevant KPIs based on weighted criteria (Mourtzis et al. 2018) or the organization’s business model configuration (di Valentin et al. 2013; Nielsen et al. 2017).

Existing research provides different ways to support the operationalization of business model KPIs. A few studies specify qualitative questions for each KPI to reduce complexity and guide decision-makers in assessing their selected indicators (e.g., Afuah and Tucci 2003; Díaz-Díaz et al. 2017; Wirtz 2020). Moreover, six studies provide formulas to express how a particular KPI is calculated (e.g., Kijl and Boersma 2010; Minatogawa et al. 2019; Wirtz 2020). Lastly, four studies propose representing the relationships between KPIs in a conceptual model (Bouwman 2003; Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al. 2015; Morioka et al. 2016; Minatogawa et al. 2019). Relationships between KPIs are modeled to show cause-and-effect relationships (Minatogawa et al. 2019) or represent the links between a KPI and the resources and activities of an organization (Morioka et al. 2016).

Concerning the measurement of business model KPIs, existing research proposes several ways to collect and measure relevant data. The most frequently reported way to collect qualitative data is by organizing workshops and interviews with responsible managers of the focal organization (e.g., Heikkilä et al. 2016; Kijl and Boersma 2010; Montemari et al. 2019). Moreover, some studies propose carrying out surveys among employees, external partners, or customers (e.g., Heikkilä et al. 2014; Kostin et al. 2021). Other methods for data collection include inspecting financial statements (e.g., Bouwman and van den Ham 2004; Morioka et al. 2016) and studying public information (Dubosson-Torbay et al. 2002; Díaz-Díaz et al. 2017; Stalmachova et al. 2022). Furthermore, several authors suggest retrieving data from an organization’s IT systems, for instance, by querying ERP systems and databases (di Valentin et al. 2012b; Augenstein and Fleig 2018) or analyzing a company’s website data (Bouwman and van den Ham 2004; Minatogawa et al. 2019).

To report the measured values of KPIs in a single report, we observe the use of scorecards (Osterwalder et al. 2005; Batocchio et al. 2017), matrix overviews (Kastalli et al. 2013), radar charts (Díaz-Díaz et al. 2017), and line charts (Minatogawa et al. 2019). For the continuous monitoring and reporting of KPIs, four studies provide software prototypes and design principles for dashboards to visualize business model performance data (di Valentin et al. 2013; Augenstein and Fleig 2018; Mourtzis et al. 2018; Schaffer et al. 2020).

4.2.3 Stage of use of the approach

In approaches used in the ex-ante realization stage of the business model, KPIs are defined and evaluated to make predictive analyses and reduce business model risks (Kijl and Boersma 2010; Augenstein and Fleig 2018). Several authors propose to use KPIs to make estimations about business model performance in future scenarios (e.g., Heikkilä et al. 2010; Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al. 2015). Moreover, a few studies propose methods and frameworks that support benchmarking business model alternatives or comparing an organization’s business model with competitors (e.g., Afuah and Tucci 2003; Morioka et al. 2016). Benchmarks of business model performance against competitors or alternative business models can be carried out both in the ex-ante or ex-post realization of a business model.

In the ex-post realization of the business model, KPIs are used to gather insights about current or past business model performance (Batocchio et al. 2017). For this stage, we found several studies that present software instantiations to support the continuous monitoring of business model KPIs and track the dynamics and performance of a business model in operation (e.g., di Valentin et al. 2013; Schaffer et al. 2020). By keeping track of business model KPIs, managers can compare the actual performance of a business model with its expected performance (Globocnik et al. 2020). In case the performance of a business model is observed to deflect, responsible managers may be triggered to create detailed action plans for re-designing the business model, for example, by adapting the business model’s underlying business processes (di Valentin et al. 2012a; Suratno et al. 2018).

4.2.4 Type of key performance indicators

In the literature, two studies introduce approaches that are exclusively focused on qualitative KPIs. Gilsing et al. (2021b) present a method for defining qualitative KPIs for business models using protoforms based on linguistic summarization theory. An example of a protoform that includes a KPI and an expected value is: Most customers use the service easily. These soft-quantified KPIs can gradually be concretized and quantified during later phases when the business model is implemented (Gilsing et al. 2021b). Moreover, Díaz-Díaz et al. (2017) introduce a questionnaire-based evaluation approach, including 29 qualitative questions to assess the business model based on six KPIs. The answers to the questions are translated into quantifiable levels to assess business model performance.

Seven studies provide approaches that focus exclusively on quantitative KPIs. Most of these studies focus on financial KPIs such as product price, operational costs, and return on investment (e.g., Afuah and Tucci 2003). For example, based on expert interviews, Kijl and Boersma (2010) derive the following finance-related KPIs: total turnover, gross margin, profit after tax, margin per e-mail, re-investable profit, and investment portfolio value.

Many studies make use of a combination of both qualitative and quantitative KPIs. In these studies, quantitative KPIs are often measured first to calculate an aggregated qualitative KPI. For instance, Kastalli et al. (2013) propose a “complementarity index” as a critical KPI for manufacturing firms that adopt PSS business models. The value of this index is calculated based on sales numbers (i.e., quantitative KPI) for both products and services. Subsequently, the index can indicate a negative, substitutive, positive, or complementary relationship (i.e., qualitative KPI) between a company’s product and service offering (Kastalli et al. 2013).

4.2.5 Context for which the approach is designed

While some studies provide approaches for managing KPIs in the context of business models in general, most methods and tools in the literature are developed with a focus on a specific type of business model. In total, 24 of the 35 studies are developed for a specific context. Six studies were dedicated to business models of networked organizations (e.g., Bouwman 2003; Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al. 2015; Gilsing et al. 2021b). In this type of business model, multiple organizations collaborate in a networked setting to co-create and deliver value to the customer (Bouwman et al. 2008; Turetken et al. 2019). Next, e-business was the context for which most KPI management approaches were developed. In this context, we identified studies related to internet business models (e.g., Palanisamy 2001) and e-commerce (e.g., Udo and Ishino 2021). Another context comprising multiple studies is the context of PSS business models (Kastalli et al. 2013; Mourtzis et al. 2018). PSS is a specific business model in which tangible products are combined with intangible services in a single system (Goedkoop et al. 1999). Moreover, two studies by di Valentin et al. (2012b, 2013) focus on the context of business models in the software industry. Specific KPIs relevant to software industry business models include the number of service requests, number of bugs, and number of implementation inquiries (di Valentin et al. 2013). We found two publications that provide approaches dedicated to sustainable business models by Lüdeke-Freund et al. (2017) and Morioka et al. (2016). Sustainable business models contribute to the sustainable development of business and society by positioning themselves in an ecologically and socially sound way, for example, through improving their production efficiency or product responsibility (Lüdeke-Freund et al. 2017). Other contexts for which specific KPI management approaches are developed include start-ups (Batocchio et al. 2017), manufacturing (Kostin et al. 2021), human resources (Khoshalhan and Kaldi 2007), healthcare (Kriegel et al. 2016), financial services (Stalmachova et al. 2022), and e-government (Yu 2014).

4.3 Catalog of business model key performance indicators

To identify which business model KPIs are referred to in the literature, we reviewed the selected sample of publications to extract any KPI, performance indicator, measure, or metric related to business models. The final catalog consists of 215 business model KPIs and corresponding operationalization and is presented at https://sites.google.com/view/catalogofkpisforbusinessmodels. The KPIs were categorized along four business model pillars and 12 business model dimensions (Table 2).

Figure 7 presents the number of identified KPIs per business model pillar and dimension. It shows that most KPIs are related to the Profit formula pillar of business models (73 out of 215 indicators). In comparison, the Frontstage pillar (69 indicators) and Backstage pillar (51 indicators) are also covered by many KPIs. On the other hand, we found only 22 indicators related to the Context pillar of business models. These statistics show that most KPIs in the literature are catered toward the three original pillars of the Business Model Canvas: Frontstage, Backstage, and Profit formula (Osterwalder et al. 2020). KPIs related to the Context pillar seem largely overlooked in the current literature on business model KPIs.

The number of identified KPIs highly differs across different business model dimensions. As shown in Fig. 7, the Cost Structure dimension accounts for the highest number, with 31 KPIs. This number might be explained by the fact that costs play a critical role in assessing the business case of new business models (Daas et al. 2013) and controlling the performance of an existing business model (Wirtz 2020). Channel performance is the dimension with the second-highest number of KPIs, with 28 in total, and is part of the Frontstage dimension. These figures align with Wirtz et al. (2016)’s argument that an organization’s customer interface is of great importance for a business model’s success. At the same time, only a few KPIs were extracted related to the business model’s sustainability and societal performance (six KPIs, respectively). Although we observe an increasing interest in evaluating sustainability and societal performance of business models (Lüdeke-Freund et al. 2017; Schoormann et al. 2018; Süß et al. 2021), there are only a few KPIs associated with this business model dimension compared to the other dimensions in the catalog. Finally, we found that the KPIs categorized in the Key Activities dimension are most related to the business processes that enable the operation of a business model. Examples of KPIs in this category include process throughput, process duration, and process lead time.

Table 3 presents the most frequently used or mentioned business model KPIs in the academic literature. The corresponding business model dimension and operationalization are presented for each KPI, including the number of studies in our selected sample that mention or use the KPI. The most used business model KPIs are ‘Product or service quality’ (part of the value propositions dimension) and ‘Customer satisfaction’ (part of the customer relationships dimension), which both appear in 14 studies. The second-most used or referred to KPIs are ‘Perceived customers benefit’ and ‘Satisfaction of customer needs’, which are mentioned in 13 studies.

5 Discussion

This section discusses our studies’ contributions to research and practice, limitations, and possible avenues for future research.

5.1 Contributions to research

The objective of our research was to analyze and consolidate the current state of research on KPIs for business models. For this purpose, we analyzed the 35 selected sources and located a variety of models, methods, and instantiations for managing business model KPIs. We investigated the characteristics of the identified approaches and classified them into a concept matrix consisting of five categories related to business models and KPI management.

Business model researchers should consider our concept matrix as a comprehensive overview of the literature on business model KPIs that can serve as a basis for further research. First, we found that existing approaches for managing business model KPIs are mainly catered toward the definition of KPIs. The methods and tools presented in the literature are often used to define new business model KPIs or monitor the performance of an existing business model in a specific context. However, when compared to the KPI definition, existing research provides limited support for selecting, operationalizing, and reporting business model KPIs. Moreover, while many studies present catalogs and frameworks for business model KPI management, less research has been dedicated to developing structured methods for managing business model KPIs. In addition, we found that only a few studies present software instantiations to support KPI management for business models. Most software tools and prototypes presented in the literature have either been only partially instantiated (e.g., Augenstein and Fleig 2018; Schaffer et al. 2020) or are only suitable for measuring business model performance in established organizations in which certain enterprise systems are in place (di Valentin et al. 2013). The proposed instantiations might therefore be less applicable to start-up organizations and SMEs. Lastly, our research shows that several studies offer an integrated approach for supporting business model KPI management through all phases of the KPI management lifecycle, i.e., defining, selecting, operationalizing, measuring, and reporting. In total, we found three studies that provide methods or tools that address, to a certain extent, all five phases of the KPI lifecycle (Batocchio et al. 2017; Mourtzis et al. 2018; Minatogawa et al. 2019). Our analysis points out several gaps in the existing literature, which may serve as future research opportunities on business model KPIs and how they can be managed (see Sect. 5.4).

To identify which business model KPIs are referred to in the academic literature and synthesize them into a catalog, we analyzed the sampled studies from our literature review that mentioned or used KPIs. Based on an iterative process of categorization and synthesis, we developed a catalog consisting of 215 KPIs related to business models. We categorized them into four business model pillars (Frontstage, Backstage, Profit formula, and Context) and 12 dimensions relevant to business model performance (value proposition performance, customer relationship performance, customer segment performance, channel performance, key activity performance, key resource performance, key partner performance, revenue stream performance, cost structure performance, profitability performance, market performance, and sustainability & society performance). For each KPI in the catalog, we provide an operationalization and the academic publications that mention or use it.

The results of our review give insight into the current body of knowledge on business model KPIs. Our citation analysis indicates that the sampled articles from the literature form a tightly coupled network. Thus, the authors of publications on business model KPIs seem to support and build on the existing body of knowledge. We found several academic studies that present lists or catalogs of KPIs for business models (e.g., Dubosson-Torbay et al. 2002; di Valentin et al. 2013; Heikkilä et al. 2016). However, more than half of the sampled studies did not provide a clear operationalization for part (or all) of the suggested KPIs. Thus, the existing literature lacks in guiding how to measure KPIs concretely. Our research goes beyond the state of the art by providing a catalog of KPIs, including an operationalization for each KPI. The explicit operationalization of the KPIs can be used for measuring the performance of existing or new business models. Thereby our research is a response to the performative research agenda for business models by Nielsen et al. (2018) and the calls for future research on the intersection between business models and performance measurement (Burkhart et al. 2011; Lambert and Montemari 2017).

5.2 Contributions to practice

The concept matrix developed in this study can guide managers in selecting relevant models, methods, and instantiations for specifying KPIs and monitoring the performance of their organization’s business models. Nevertheless, in practice, the specific context of a business model and the needs of an organization still need to be considered when selecting the KPI management approaches identified in this study. Moreover, the catalog of KPIs presented in this study can be used by practitioners who aim to define and concretize KPIs for their organization’s business models. The KPIs depicted in the catalog can be tailored to specific business model contexts. Our catalog explicitly helps in the phases of definition, selection, and operationalization, which have not been studied much in the current literature. As the KPIs in the catalog are categorized based on business model dimensions, the selection of KPIs can be guided much better. Since organizations need to evaluate different dimensions of their business models, managers can use the catalog to select and specify KPIs that fit their organization’s specific business model dimensions.

5.3 Limitations

Despite following a rigorous research approach (Webster and Watson 2002; Wohlin 2014; Okoli 2015), our study is subject to some limitations that should be taken into consideration. First, we initially focused on business model studies that included any type of KPI. We then broadened our results to also encompass approaches related to the management of business model KPIs. Second, the terminology around business model KPIs, performance indicators, measures, and metrics is used in diverse ways, and these terms have multiple definitions in the literature. Since we treated these terms as synonyms in this study, a certain level of subjectivity may have been involved in selecting relevant studies and synthesizing the KPIs into a catalog. To minimize this effect, multiple authors of this paper were involved throughout the entire research process. Third, we use the dimensions of the BMC and related business model pillars to categorize the KPIs identified in the literature. A main limitation of the BMC is that it takes the perspective of a single organization, as opposed to a networked-oriented perspective on business models (e.g., Bouwman et al. 2008; Heikkilä et al. 2010; Turetken et al. 2019). The BMC focuses on the activities and resources under the control of the focal organization and does not differentiate between suppliers, complementary vendors, and other partner organizations in the strict sense of the word. In our catalog, we categorized KPIs related to the performance of the business network in the ‘key partners’ dimension. Although the KPIs in the catalog can be tailored to an organization’s specific needs, in its current form, it might pose challenges for defining specific KPIs for networked business models featuring multiple partners. Therefore, future research can adopt a network-oriented approach to business model performance and focus on identifying and categorizing relevant KPIs for managing network-based business models. Fourth, the KPI catalog developed in this paper is still of conceptual nature. Therefore, future research should focus on empirically validating and applying it in different business contexts to enhance and confirm its validity and utility. Lastly, our study included only academic literature. Future studies should also consider including grey literature (e.g., Gartner 2021) to provide a broader and more extensive view of business model KPI management and related KPIs.

5.4 Avenues for future research

Based on the results and limitations of our study, we outline several avenues for future research.

5.4.1 Future research on business model KPI management

To move beyond the definition of KPIs and to increase the effectiveness of business model KPI management, future research should focus on developing step-by-step methods for managing business model KPIs. In doing so, researchers can build on KPIs and performance measurement models presented in the existing literature. For instance, future studies can focus on developing a structured method to select KPIs from a catalog and tailor them to an organization’s specific needs. Developing new methods for defining, specifying, and measuring business model KPIs can support decision-makers in assessing alternative business models and evaluating the performance of business models that are already in operation (Batocchio et al. 2017; Minatogawa et al. 2019). We recommend using design science research (DSR) (Peffers et al. 2007; Gregor and Hevner 2013) and situational method engineering (SME) approaches (Brinkkemper 1996; Henderson-Sellers and Ralyté 2010) to design and evaluate these new methods.

Second, we call for further research on developing software instantiations to support KPI management for business models. Developing software tools for managing and evaluating business models has been a major topic of interest in information systems research (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2013; Veit et al. 2014; Szopinski et al. 2020). The design principles and requirements in existing studies can provide initial guidelines for further development and implementation of these systems (e.g., Augenstein and Fleig 2018; Gilsing et al. 2021b). The formalization of selection techniques and calculation rules in existing KPI management methods can support the further development of software tools for managing business model KPIs (e.g., Del-Río-Ortega et al. 2013; Mourtzis et al. 2018). Moreover, we argue that existing knowledge from the field of enterprise modeling can inform the development of conceptual models for representing relationships between different business model KPIs, activities, and organizational objectives (e.g., Popova and Sharpanskykh 2010; Strecker et al. 2012).

Third, future research can focus on the design of integrated approaches for other business model contexts that support all phases of the KPI lifecycle. Specifically, we see an opportunity to build on the existing knowledge and experience in the PSS domain (Mourtzis et al. 2018) to develop an integrated method and tool for the general context of business models.

5.4.2 Future research on business model KPIs