Abstract

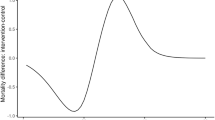

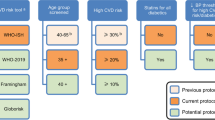

The objective of this article was to assess the cost-effectiveness of screening strategies for cardiovascular diseases (CVD). A decision analytic model was constructed to estimate the costs and benefits of one-off screening strategies differentiated by screening age, sex and the threshold for initiating statin therapy (“uniform” or “age-adjusted”) from the Spanish NHS perspective. The age-adjusted thresholds were configured so that the same number of people at high risk would be treated as under the uniform threshold. Health benefit was measured in quality-adjusted life years (QALY). Transition rates were estimated from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-CVD), a large multicentre nested case-cohort study with 12 years of follow-up. Unit costs of primary care, hospitalizations and CVD care were taken from the Spanish health system. Univariate and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were employed. The comparator was no systematic screening program. The base case model showed that the most efficient one-off strategy is to screen both men and women at 40 years old using a uniform risk threshold for initiating statin treatment (Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio of €3,274/QALY and €6,085/QALY for men and women, respectively). Re-allocating statin treatment towards younger individuals at high risk for their age and sex would not offset the benefit obtained using those same resources to treat older individuals. Results are sensitive to assumptions about CVD incidence rates. To conclude, one-off screening for CVD using a uniform risk threshold appears cost-effective compared with no systematic screening. These results should be evaluated in clinical studies.

Source of data: EPIC-CVD case-cohort study

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sanderson, J.E., Mayosi, B., Yusuf, S., Reddy, S., Hu, S., Chen, Z., et al.: Global burden of cardiovascular disease. Heart (2007). https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2007.131060

Visseren, F.L.J., Mach, F., Smulders, Y.M., Carballo, D., Koskinas, K.C., Bäck, M., et al.: 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484

Department of Health. Putting Prevention First. Vascular Checks: Risk Assessment and Management. http://data.parliament.uk/DepositedPapers/Files/DEP2008-0910/DEP2008-0910.pdf (2008). Accessed 2 Jul 2021

Yebyo, H.G., Aschmann, H.E., Puhan, M.A.: Finding the balance between benefits and harms when using statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a modeling study. Ann. Intern. Med. (2019). https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-1279

Perk, J., De Backer, G., Gohlke, H., Graham, I., Reiner, Ž, Verschuren, W.M.M., et al.: European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (Version 2012). Int. J. Behav. Med. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9242-5

Moons, K.G.M., Kengne, A.P., Woodward, M., Royston, P., Vergouwe, Y., Altman, D.G., et al.: Risk prediction models: I. Development, internal validation, and assessing the incremental value of a new (bio)marker. Heart (2012). https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjn1-2011-301246

Dyakova, M., Shantikumar, S., Colquitt, J.L., Drew, C.M., Sime, M., Maclver, J., et al.: Systematic versus opportunistic risk assessment for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010411.pub2

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181/chapter/implementation-getting-started (2016). Accessed 6 Nov 2020.

Epstein, D., García-Mochón, L., Kaptoge, S., Thompson, S.G.: Modeling the costs and long-term health benefits of screening the general population for risks of cardiovascular disease: a review of methods used in the literature. Eur. J. Heal. Econ. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-015-0753-2

Lagerweij, G.R., de Wit, G.A., Moons, K.G.M., van der Schouw, Y.T., Veschuren, W.M.M., Dorresteijn, J.A.N., et al.: A new selection method to increase the health benefits of CVD prevention strategies. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487317752948

D’Agostino, R.B., Vasan, R.S., Pencina, M.J., Wolf, P.A., Cobain, M., Massaro, J.M., et al.: General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham heart study. Circulation (2008). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579

JBS2: Joint British Societies’ guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. Heart (2005). https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2005.079988

Drummond, M.F., Sculpher, M.J., Claxton, K., Stoddart, G.I., Torrance, G.W.: Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2015)

Pennells, L., Kaptoge, S., Wood, A., Sweeting, M., Zhao, X., White, I., et al.: Equalization of four cardiovascular risk algorithms after systematic recalibration: individual-participant meta-analysis of 86 prospective studies. Eur. Heart J (2019). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy653

The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group: Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N. Engl. J. Med. (1998). https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199811053391902

Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group: Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90566-5

Wang, H., Sun, W., Ji, Y., Shi, J., Xuan, Q., Wang, X., et al.: Trends in age-specific cerebrovascular disease in the european union. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 7(11), 4165–4173 (2014)

Bhatnagar, P., Wickramasinghe, K., Wilkins, E., Townsend, N.: Trends in the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in the UK. Heart (2016). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k934

Riboli, E., Hunt, K., Slimani, N., Ferrari, P., Norat, T., Fahey, M., et al.: European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection. Public Health Nutr. (2002). https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2002394

Ricci, C., Wood, A., Muller, D., Gunter, M.J., Agudo, A., Boeing, H., et al.: Alcohol intake in relation to non-fatal and fatal coronary heart disease and stroke: EPIC-CVD case-cohort study. BMJ (2018). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k934

Royston, P., Lambert, P.C.: Flexible Parametric Survival Analysis Using Stata: Beyond the Cox Model. Stata Press, College Station (2011)

Jones, E., Epstein, D., García-Mochón, L.: A procedure for deriving formulas to convert transition rates to probabilities for multistate markov models. Med. Decis. Mak (2017). https://doi.org/10.1177/027298X17696997

Taylor, F., Huffman, M.D., Macedo, A.F., Moore, T.H.M., Burke, M., Smith, G.D., et al.: Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5

Smith, D.W., Davies, E.W., Wissinger, E., Huelin, R., Matza, L.S., Chung, K.: A systematic literature review of cardiovascular event utilities. Expert Rev. Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1586/14737167.2013.841545

Dyer, M.T.D., Goldsmith, K.A., Sharples, L.S., Buxton, M.J.: A review of health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health Qual. Life Outcomes (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-13

Brugts, J.J., Yetgin, T., Hoeks, S.E., Gotto, A.M., Shepherd, J., Westendorp, R.G.J., et al.: The benefits of statins in people without established cardiovascular disease but with cardiovascular risk factors: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ (2009). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2376

Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía n°210. Orden de 14 de octubre de 2005, por la que se fijan los precios públicos de los servicios sanitarios prestados por Centros dependientes del Sistema Sanitario Público de Andalucía. Portal de la Junta de Andalucía. https://juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2005/210/boletin.210.pdf. (2005). Accessed 23 Jul 2020

Petek, D., Petek-Ster, M., Tusek-Bunc, K.: Health behavior and health-related quality of life in patients with a high risk of cardiovascular disease. Zdr. Varst. (2018). https://doi.org/10.2478/sjph-2018-0006

Navarro Moya, F., Carnero Pardo, C., Daponte Codina, A., del Río Urenda, S., Díez de los Ríos Carrasco, A., Domínguez Marmolejo, A., et al.: Proceso Asistencial Integrado. Riesgo vascular. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía. Consejería de Salud (2010)

Alva, M.L., Gray, A., Mihaylova, B., Leal, J., Holman, R.R.: The impact of diabetes-related complications on healthcare costs: New results from the UKPDS (UKPDS 84). Diabet. Med. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12647

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Cálculo de variaciones del Indice de Precios de Consumo. http://www.ine.es/varipc/. Accessed 10 Aug 2016.

BotPlus. https://botplusweb.portalfarma.com/botplus.aspx. Accessed 23 Jul 2021.

Martín Ruiz, E., Olry de Labry, A., Epstein, D.: Prevención primaria de enfermedades cardiovasculares: una revisión de revisiones de intervenciones no farmacológicas. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 41(3), 355–369 (2018)

Lemstra, M., Blackburn, D., Crawley, A., Fung, R.: Proportion and risk indicators of nonadherence to statin therapy: a meta-analysis. Can. J. Cardiol (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2012.05.007

Martin-Ruiz, E., Olry-de-Labry-Lima, A., Ocaña-Riola, R., Epstein, D.: Systematic review of the effect of adherence to statin treatment on critical cardiovascular events and mortality in primary prevention. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/1074248417745357

Ministro de Sanidad. Resultados según la versión 32 de los APR-GRD. Registro de Altas de los Hospitales Generales del Sistema Nacional de Salud. CMBD. Norma Estatal de Años Anteriores. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/cmbdAnteriores.htm (2017). Accessed 20 Dec 2020.

Ara, R., Brazier, J.E.: Using health state utility values from the general population to approximate baselines in decision analytic models when condition-specific data are not available. Value Heal. (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2010.10.029

Epstein, D.: Beyond the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve: The appropriateness of rank probabilities for presenting the results of economic evaluation in multiple technology appraisal. Health Econ. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3884

Vallejo-Torres, L., García-Lorenzo, B., Serrano-Aguilar, P.: Estimating a cost-effectiveness threshold for the Spanish NHS. Health Econ. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3633

Eriksen, C., Rotar, O., Toft, U., Jørgensen, T.: What is the effectiveness of systematic population-level screening programmes for reducing the burden of cardiovascular diseases? Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2021 (WHO Health Evidence Nerwork (HEN) Evidence Synthesis Report 71). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/338530/9789289055376-eng.pdf. Accessed 2 Jan 2021.

Johannesson, M.: At what coronary risk level is it cost-effective to initiate cholesterol lowering drug treatment in primary prevention? Eur. Heart J. (2001). https://doi.org/10.1053/euhj.2000.2484

Damen, J.A., Tajouheshnia, R., Heus, P., Moons, K.G.M., Reitsma, J.B., Scholten, R.J.P.M., et al.: Performance of the Framingham risk models and pooled cohort equations for predicting 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1340-7

Joy, T.R., Hegele, R.A.: Narrative review: statin-related myopathy. Ann. Intern. Med. (2009). https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-12-200906160-00009

Ahmad, Z.: Statin intolerance. Am. J. Cardiol. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.02.033

Wood, F.A., Howard, J.P., Finegold, J.A., Nowbar, A.N., Thompson, D.M., Arnold, A.D., et al.: N-of-1 trial of a statin, placebo, or no treatment to assess side effects. N. Engl. J. Med. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2031173

Martín Ruiz, E., Olry-de-Labry-Lima, A., Epstein, D.: The benefits and risks of statins for primary prevention of mortality and cardiovascular events: umbrella review. Eur J Clin Pharm. 18(5), 335–340 (2016)

Goff, D.C., Lloyd-Jones, D.M., Bennett, G., Coady, S., D’Agostino, R.B., Gibbons, R., et al.: 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American college of cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.005

Kypridemos, C., Allen, K., Hickey, G.L., Guzman-Castillo, M., Bandosz, P., Buchan, I., et al.: Cardiovascular screening to reduce the burden from cardiovascular disease: Microsimulation study to quantify policy options. BMJ (2016). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2793

Patel, R., Barnard, S., Thompson, K., Lagord, C., Clegg, E., Worrall, R., et al.: Evaluation of the uptake and delivery of the NHS Health Check programme in England, using primary care data from 9.5 million people: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open (2020). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042963

Heller, D.J., Coxson, P.G., Penko, J., Pletcher, M.J., Goldman, L., Odden, M.C., et al.: Evaluating the impact and cost- effectiveness of statin use guidelines for primary prevention of coronary heart disease and stroke. Circulation (2017). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027067

Acknowledgements

The national cohorts are supported by: Danish Cancer Society (Denmark); Ligue Contre le Cancer, Institut Gustave Roussy, Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) (France); German Cancer Aid, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbruecke (DIfE), Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (Germany); Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro-AIRC-Italy, Compagnia di SanPaolo and National Research Council (Italy); Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS), Netherlands Cancer Registry (NKR), LK Research Funds, Dutch Prevention Funds, Dutch ZON (Zorg Onderzoek Nederland), World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF), Statistics Netherlands (The Netherlands); Health Research Fund (FIS)—Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Regional Governments of Andalucía, Asturias, Basque Country, Murcia and Navarra, and the Catalan Institute of Oncology—ICO (Spain); Swedish Cancer Society, Swedish Research Council and County Councils of Skåne and Västerbotten (Sweden); Cancer Research UK (14136 to EPIC-Norfolk; C8221/A29017 to EPIC-Oxford), Medical Research Council (1000143 to EPIC-Norfolk; MR/M012190/1 to EPIC-Oxford). (United Kingdom), Hyblean Association for Epidemiological Research, AIRE ONLUS, EPIC-Ragusa (Italy).

Funding

The EPIC-CVD coordinating centre was supported by core funding from the European Commission Framework Programme 7 (HEALTH-F2-2012-279233), European Research Council (268834), Novartis, UK Medical Research Council (G0800270; MR/L003120/1), British Heart Foundation (SP/09/002; RG/13/13/30194; RG/18/13/33946) and NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014). The study was also supported by International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics (School of Public Health, Imperial College London) and the Spanish Association of Health Economics (Research Fellowship on Health Economics and Health Services, 12,000€).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Design of the study: LGM, JE, DE. Data collection: MRB, MJSP, AT, SG, CS, GM, GE, MBS. Estimation of the age-adjusted risk thresholds: SK, LB. Analysis and interpretation of data: ZS, DE, LB, LGM. Drafting the article: ZS, DE. Critical revision of the article: NPB, AT, EW, CS, CSch, SMCY, LK, KGMM, GE, MBS, CMI. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material. The spreadsheets related to this article is available under doi: 10.17632/ysm4yj24xh.1.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Špacírová, Z., Kaptoge, S., García-Mochón, L. et al. The cost-effectiveness of a uniform versus age-based threshold for one-off screening for prevention of cardiovascular disease. Eur J Health Econ 24, 1033–1045 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01533-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01533-y