Abstract

Background

Double disruptions of the superior suspensory shoulder complex, commonly referred to as ‘floating shoulder’ injuries, are ipsilateral midshaft clavicular and scapular neck/body fractures with a loss of bony attachment of the glenoid. The treatment of ‘floating shoulder’ injuries has been debated controversially for many years. The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the clinical and functional outcomes of patients with ‘floating shoulder’ injuries who underwent operative fixation of the clavicle fracture only.

Materials and methods

Between 2002 and 2010, 32 consecutive floating shoulder injuries were identified in skeletally mature patients at a level I trauma center and followed in a single private practice. Thirteen patients met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this retrospective study with a minimum 12-month follow-up. Clavicle and scapular fractures were identified by Current Procedural Technology codes and classified based on Orthopaedic Trauma Association/Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen criteria. ‘Floating shoulder’ injuries were surgically managed with only clavicular reduction and fixation utilizing modern plating techniques. Nonunion, malunion, implant removal, range of motion, need for secondary surgery, pain according to the visual analog scale (VAS), and return to work were measured.

Results

All injuries were the result of high-energy mechanisms. Fracture union of the clavicle was seen after initial surgical fixation in the majority of patients (12; 92.3 %). Final pain was reported as minimal (11 cases; 1–3 VAS), moderate (1 case; 4–6 VAS), and high (1 case; 7–10 VAS) at last follow-up. Excellent range of motion (180° forward flexion and abduction) was observed in the majority of patients (8; 61.5 %). The Herscovici score was 12.9 (range 10–15) at 3 months. Unplanned surgeries included two clavicular implant removals and one nonunion revision. None of the patients required reconstruction for scapula malunion after nonoperative management. Twelve patients returned to previous work without restrictions.

Conclusions

‘Floating shoulder’ injuries with only clavicular fixation return to function despite persistent scapular deformity and some residual pain.

Level of evidence Level IV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Double disruptions of the superior suspensory shoulder complex (SSSC) resulting in ipsilateral midshaft clavicular and scapular body/neck fractures, are commonly referred to as a ‘floating shoulder’ injury, and result in a loss of bony attachment of the glenoid [1, 2]. Floating shoulder injuries are the result of high-energy mechanisms [3–5] with an incidence of approximately 0.10 % of trauma patients [6]. Although much is known about these fractures when they occur in isolation, evidence is lacking in regard to treatment as concomitant fractures are associated with poor cosmesis, reduced strength, and dyskinesia of the shoulder girdle. Ganz and Noesberger [7] originally suggested that the weight of the arm and the muscles at the humerus would cause caudal and anteromedial displacement of the glenoid. Ada and Miller [3] found high numbers of rotator cuff dysfunction in patients with displaced clavicular and scapular fractures, as the normal lever arm of the rotator cuff is lost with glenoid displacement.

The treatment of ‘floating shoulder’ injuries has been debated over many years. Several studies recommend that conservative treatment results in acceptable patient outcomes, especially when fractures are minimally displaced [8–13]. Other studies have reported good to excellent outcomes with only clavicular fixation [6, 14–17]. In floating shoulder injuries with significant displacement, some studies have recommended fixation of both clavicular and scapular fractures [11, 13, 18–20]. Despite cited surgical indications for isolated extra-articular and intra-articular scapular fractures [3, 21–25], validated indications for ‘floating shoulder’ surgical management remain unclear. The purpose of this study was to describe the clinical and functional outcomes of patients with displaced and unstable ‘floating shoulder’ injury following fixation of only the clavicular fracture.

Materials and methods

This Institutional Review Board-approved retrospective exploratory study reviewed operatively treated midshaft clavicular fractures with associated ipsilateral non-operatively treated scapular fractures. The patients were recruited from a private practice office associated with a level I teaching trauma center. Consecutive patients were identified using Current Procedural Technology coding for operatively fixed clavicle fractures (23515) and a scapular injury database from March 1, 2002 to October 1, 2010.

Operative criteria for clavicular fixation included significant clavicular shortening (>20 mm on either anterior-posterior [AP], cephalad, or caudal radiographs), associated neurological injury, associated unstable scapular injury (glenoid neck, acromion, coracoid, or intra-articular glenoid fractures), double suspensory shoulder instability, open clavicular fractures, published criteria for displacement, impending skin compromise, or polytrauma [26–30]. Inclusion criteria for this study were skeletally mature (age ≥18 years), ipsilateral middle third clavicular fracture and scapular fracture meeting the definition of a ‘floating shoulder’, clavicle fixation utilizing modern plating techniques [27, 31–33], and a minimum 12-month follow-up. A total of 32 patients were identified during this time period. Nineteen patients were excluded due to initial non-operative treatment of the clavicle fracture with subsequent nonunion (1), incarceration (1), insufficient records or imaging (7), and operative treatment of both clavicle and scapular fractures (10). When initially planning surgical management of these patients, the indications for fixation of the scapular fracture were partly based on the preferences of the senior surgeons as well as the patient’s clinical condition. All patients in this study, with the exception of two, did not meet currently published indications for fixation of the scapular fracture in ‘floating shoulder’ injuries [11]. Thirteen ‘floating shoulder’ injuries in 13 patients formed the basis of this study.

All patients were treated and followed by four fellowship-trained orthopedic trauma surgeons utilizing similar philosophies and techniques. At the time of injury, all patients had computed tomography (CT) scans with three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the scapular fracture to assess deformity which included the glenopolar angle [34] (Fig. 1) and medialization/lateralization [35] (Fig. 2) of the scapular fragments [GE LightSpeed VCT 64-slice CT scanner; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA (1.25-mm slice thickness); 3D reconstruction with TeraRecon Aquarius iNtuition v.4.4.5.49; TeraRecon, Inc, Foster City, CA, USA].

At 1–2 weeks postoperatively, physical therapy-directed passive range of motion (ROM) was instituted in all patients. At 6 weeks postoperatively, physical therapy-directed active ROM and strengthening was started. Patients were evaluated and imaged at regular intervals of 2, 6, and 12 weeks, and ongoing according to clinical necessity including, but not limited to pain, plate irritation, plate prominence, poor ROM, or not achieving complete clinical healing. Cephalad and caudal views of the clavicle were obtained at each interval to determine healing and alignment [36]. Grashey (true shoulder AP), axillary, and scapular Y views of the shoulder were obtained at each interval to determine scapular healing and morphology. Distances and angles were measured using digital software with a picture archiving and communication system or by manual techniques and protractors. Both clavicle and scapular fracture patterns were classified according to Orthopedic Trauma Association/Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (OTA/AO) criteria [37].

Pain according to the visual analog scale (VAS) [38] and ROM using basic clinical measurements were recorded. Outcomes were further measured using the Herscovici scoring system which assigns a numerical value (1–4) for pain, lifestyle, ROM, and muscle strength with a value of 16 being the best possible outcome [6]. Return to previous work was assessed. Follow-up was for a minimum of 12 months with radiographic union and return to previous activities and/or employment being established.

Standard statistical analyses were employed. Descriptive statistics, including means, range, standard deviation, and percentages were calculated using SPSS® 18.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

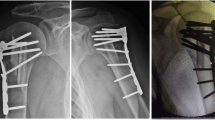

The mean follow-up was 16 months (12–45 months). The mean age at time of injury was 46 years (18–60 years) and 10 patients were male. High-energy mechanisms were the cause of all patient injuries including motorcycle accidents (11; 84.6 %) and all-terrain vehicle accidents (2; 15.4 %). None of the fractures were classified as open. Clavicular fracture classification was recorded as type 15-B1 (5; 38.4 %), type 15-B2 (7; 53.9 %), and type 15-B3 (1; 7.7 %). Scapular fracture classification was recorded as type 14-A3.1 (7; 53.9 %), type 14-A3.2 (5; 38.4 %), and type 14-C1.1 (1; 7.7 %) (Fig. 3). All clavicle fractures were unstable with shortening averaging 14 mm (6–30 mm) and translation averaging 10 mm (2–24 mm). Associated injuries were found in 12 of the 13 patients (92.3 %), which included rib fractures (11; 84.6 %), ipsilateral extremity fractures (6; 46 %), pneumothorax (5; 38.4 %), intracranial hemorrhage (2; 15.4 %), and abdominal hemorrhage/laceration (2; 15.4 %). Injury and fracture data are displayed in Table 1.

Eleven of 13 (85 %) patients reported minimal pain (VAS 1–3) upon final examination. One patient (1; 7.7 %) reported moderate levels of pain (VAS 4–6), which was attributed to overlying skin irritation at the surgical site. One patient (1; 7.7 %) reported high levels of pain (VAS 7–10) which was associated with the development of a nonunion. All patients eventually returned to work, 12 of whom had no restrictions. One patient (case 13) returned to function with restrictions secondary to pain despite complete nonunion resolution and full symmetrical strength and ROM.

Eight of 13 patients (62 %) had full symmetrical ROM (180° of forward flexion and abduction) at last follow-up. Three patients without complete restoration of ROM showed adequate ROM and function necessary to perform activities of daily living of the shoulder joint (flexion >121°, abduction >128°) [39]. Two patients exhibited suboptimal ROM at last follow-up. One of these patients (case 7) had a traumatic brain injury that impeded formalized therapy and therapy compliance. The mean Herscovici score for all patients was 12.9 at 3-month follow-up (range 10–15). Patient outcome data is categorized in Table 2.

Twelve of 13 (92 %) clavicular fractures initially healed. One infected nonunion successfully healed after debridement, antibiotics, and revision plating. All of the scapular fractures healed with radiographic evidence of malunion without further displacement. None of the scapular fractures required reconstructive surgery to realign the scapular malunion after initial conservative management.

Discussion

Stable, minimally displaced isolated clavicular and scapular fractures heal quickly and predictably with conservative nonoperative treatment [13, 40–42]. These injuries, however, are different from the unstable, displaced ‘floating shoulder’ injuries [1, 2]. ‘Floating shoulder’ injuries are rare with complex fracture patterns. This type of double SSSC injury is usually the result of high-energy trauma and often has associated ipsilateral shoulder and chest trauma.

Previous studies have described clinical outcomes following clavicular fixation of these injuries with varied results (Table 3). Herscovici et al. [6] reported on seven patients who had excellent outcomes with a Herscovici score of 13–16 after surgical fixation of only the clavicle. Two conservatively treated patients had persistent shoulder ‘drooping’, but could not undergo operative treatment due to severe injuries. An alternative randomized study of 25 patients by Yadav et al. [17] reported a significantly greater mean Herscovici score at 3 and 24 months in patients treated with clavicular fixation only compared to conservative management (13.9 vs 10.4 and 14.9 vs 13.0, respectively). Labler et al. [11] reported on 17 patients treated either conservatively, with clavicular fixation only, or with combined clavicular and scapular fixation. In their operative group, five patients showed good to excellent results (Constant–Murley scores 93–100) and four patients showed bad to fair results (Constant–Murley scores 0–86). The high Constant–Murley scores seen in the nonoperative group correlated with minimally displaced clavicular and scapular fractures suggestive of stable patterns. Van Noort et al. [12] reported that only two of seven patients had a corresponding indirect scapular reduction with only clavicular fixation, and persistent caudal displacement of the glenoid was observed in the other five patients. Fourteen of 28 conservatively treated patients showed persistent ‘drooping’ of the shoulder. Hashiguchi and Ito [14] found fracture union of all five clavicular and scapular fractures treated with only clavicular plating. Correspondingly high UCLA shoulder scores were noted. Rikli et al. [15] reported healing of 11 clavicular fractures after plating. Nine of their patients were completely pain free at last follow-up. Four patients changed jobs; however, three of these changes were secondary to concomitant injuries. Oh et al. [18] found improved mean Rowe scores in clavicular fractures treated operatively versus conservative management. Low and Lam [16] reported one good (Rowe score 70–84) and three excellent outcomes (Rowe score 85–100) after only clavicular fixation.

This study also demonstrates that ‘good’ to ‘excellent’ outcomes can be observed with only clavicle fixation in patients with floating shoulder injuries. At 3 months after fixation, we observed a mean Herscovici score of 12.9 consistent with near excellent outcomes. Four patients had good outcomes (9–12) and 9 experienced excellent outcomes (13–16) despite the severity of associated injuries and varying levels of shoulder instability. This does not correspond to the outcomes published by Yadav et al.; however, patients with associated neurovascular injuries or rib fractures requiring intervention were included in this study. We agree with previous studies and the recommendations set forth by Labler et al. that the majority of patients with floating shoulder injuries resulting in minimally displaced scapular fractures that are treated with clavicular plating may return to function despite varying levels of pain and scapular deformity [11]. On the basis of our patient outcomes, we recommend only clavicular fracture fixation for minimally displaced ‘floating shoulder’ injuries.

A weakness of this study is the retrospective design and absence of a standardized functional outcome tool such as the UCLA shoulder score, ASES shoulder scoring scale, Constant–Murley score, and disabilities of arm, shoulder, and hand (DASH) systems. No validated surgical indications for scapular fixation exist in the literature. Without validated surgical indication, surgeon and/or patient preference for nonoperative versus operative management does not exist; therefore, potential patient selection and treatment intervention bias may have occurred. All patterns were complex shoulder girdle injuries with varied stability. The strengths of this study include isolated clavicular fixation of a relatively large number of ‘floating shoulder’ injuries utilizing modern plating techniques. Patients were followed until complete fracture healing and operative site healing became stable.

Further research efforts are needed to reliably quantify scapular deformities objectively in order to determine surgical indications and the effectiveness of postoperative reduction of the glenoid following clavicular fixation. Three questions still persist regarding the ‘floating shoulder’. First, does clavicular fixation actually restore the scapula fracture component to its pre-injury anatomy [43, 44]? Secondly, is residual pain related to the combined shoulder girdle injury, clavicular fixation, and/or the scapular malunion? Lastly, would scapular fracture fixation decrease required formal physical therapy, allow patients to return to work earlier, or improve their overhead strength and endurance.

In conclusion, isolated plate fixation of the clavicular fracture in ‘floating shoulder’ injuries results in high rates of both clavicular and scapular fracture healing with good to excellent outcomes. Despite varying persistent shoulder girdle pain and scapular malunion, the majority of patients returned to previous work.

References

Owens BD, Goss TP (2006) The floating shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 88B:1419–1424

Goss T (1993) Double disruptions of the superior shoulder suspensory complex. J Orthop Trauma 7:99–106

Ada JR, Miller ME (1991) Scapular fractures—analysis of 113 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res (269):174–180

Thompson DA, Flynn TC, Miller PW, Fischer RP (1985) The significance of scapular fractures. J Trauma-Injury Infect Crit Care 25:974–977

Imatani RJ (1975) Fractures of scapula—review of 53 fractures. J Trauma-Injury Infect Crit Care 15:473–478

Herscovici D, Fiennes A, Allgower M, Ruedi TP (1992) The floating shoulder—ipsilateral clavicle and scapular neck fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br 74:362–364

Ganz R, Noesberger B (1975) Treatment of scapular fractures. Hefte Unfallheilkd 126:59–62

Edwards SG, Whittle AP, Wood GW (2000) Nonoperative treatment of ipsilateral fractures of the scapula and clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Am 82A:774–780

Ramos L, Mencia R, Alonso A, Ferrandez L (1997) Conservative treatment of ipsilateral fractures of the scapula and clavicle. J Trauma-Injury Infect Crit Care 42:239–242

Egol KA, Connor PM, Karunakar MA, Sims SH, Bosse MJ, Kellam JF (2001) The floating shoulder: clinical and functional results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 83A:1188–1194

Labler L, Platz A, Weishaupt D, Trentz O (2004) Clinical and functional results after floating shoulder injuries. J Trauma-Injury Infect Crit Care 57:595–602

van Noort A, Slaa RLT, Marti RK, van der Werken C (2001) The floating shoulder—a multicentre study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 83B:795–798

Cole PA, Gauger EM, Schroder LK (2012) Management of scapular fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 20:130–141

Hashiguchi H, Ito H (2003) Clinical outcome of the treatment of floating shoulder by osteosynthesis for clavicular fracture alone. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 12:589–591

Rikli D, Regazzoni P, Renner N (1995) The unstable shoulder girdle—early functional treatment utilizing open reduction and internal-fixation. J Orthop Trauma 9:93–97

Low CK, Lam AWM (2000) Results of fixation of clavicle alone in managing floating shoulder. Singapore Med J 41:452–453

Yadav V, Khare G, Singh S, Kumaraswamy V, Sharma N, Rai A, Ramaswamy A, Sharma H (2013) A prospective study comparing conservative with operative treatment in patients with a ‘floating shoulder’ including assessment of the prognostic value of the glenopolar angle. Bone Joint J 95-B:815–819

Oh CW, Jeon IH, Kyung HS, Park BC, Kim PT, Ihn JC (2002) The treatment of double disruption of the superior shoulder suspensory complex. Int Orthop 26:145–149

Leung KS, Lam TP (1993) Open reduction and internal-fixation of ipsilateral fractures of the scapular neck and clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Am 75A:1015–1018

Fleischmann W, Kinzl L (1993) Philosophy of osteosynthesis in shoulder fractures. Orthopedics 16:59–63

Khallaf F, Mikami A, Al-Akkad M (2006) The use of surgery in displaced scapular neck fractures. Med Princ Pract 15:443–448

Herrera DA, Anavian J, Tarkin IS, Armitage BA, Schroder LK, Cole PA (2009) Delayed operative management of fractures of the scapula. J Bone Joint Surg Br 91B:619–626

Jones CB, Cornelius JP, Sietsema DL, Ringler JR, Endres TJ (2009) Modified Judet approach and minifragment fixation of scapular body and glenoid neck fractures. J Orthop Trauma 23:558–564

Mayo KA, Benirschke SK, Mast JW (1998) Displaced fractures of the glenoid fossa—results of open reduction and internal fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res (347):122–130

Kavanagh BF, Bradway JK, Cofield RH (1993) Open reduction and internal-fixation of displaced intraarticular fractures of the glenoid fossa. J Bone Joint Surg Am 75A:479–484

Lazarides S, Zafiropoulos G (2006) Conservative treatment of fractures at the middle third of the clavicle: the relevance of shortening and clinical outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 15:191–194

Zlowodzki M, Zelle BA, Cole PA, Jeray K, McKee MD (2005) Treatment of acute midshaft clavicle fractures: systematic review of 2144 fractures—On behalf of the Evidence-Based Orthopaedic Trauma Working Group. J Orthop Trauma 19:504–507

Potter JM, Jones C, Wild LM, Schemitsch EH, McKee MD (2007) Does delay matter? The restoration of objectively measured shoulder strength and patient-oriented outcome after immediate fixation versus delayed reconstruction of displaced midshaft fractures of the clavicle. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 16:514–518

Kim W, McKee MD (2008) Management of acute clavicle fractures. Orthop Clin North Am 39:491–505

Altamimi SA, McKee MD, Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma S (2008) Nonoperative treatment compared with plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90 Suppl 2 Pt 1:1–8

Jones CB, Sietsema DL, Ringler JR, Endres TJ, Hoffmann MF (2013) Results of anterior-inferior 2.7-mm dynamic compression plate fixation of midshaft clavicular fractures. J Orthop Trauma 27:126–129

Collinge C, Devinney S, Herscovici D, DiPasquale T, Sanders R (2006) Anterior-inferior plate fixation of middle-third fractures and nonunions of the clavicle. J Orthop Trauma 20:680–686

McKee MD, Kreder HJ, Mandel S, McCormack R, Reindl R, Pugh DMW, Sanders D, Buckley R, Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma S (2007) Nonoperative treatment compared with plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures—a multicenter, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89A:1–10

Bestard E, Schvene H (1986) Glenoplasty in the management of recurrent shoulder dislocation. Contemp Orthop 12:47–55

Armitage BM, Wijdicks CA, Tarkin IS, Schroder LK, Marek DJ, Zlowodzki M, Cole PA (2009) Mapping of scapular fractures with three-dimensional computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91A:2222–2228

Sharr JRP, Mohammed KD (2003) Optimizing the radiographic technique in clavicular fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 12:170–172

Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, Broderick JS, Creevey W, DeCoster TA, Prokuski L, Sirkin MS, Ziran B, Henley B, Audige L (2007) Fracture and dislocation classification compendium-2007—Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma 21:S1–S133

Scott J, Huskisson EC (1976) Graphic representation of pain. Pain 2:175–184

Namdari S, Yagnik G, Ebaugh DD, Nagda S, Ramsey ML, Williams GR, Mehta S (2012) Defining functional shoulder range of motion for activities of daily living. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 21:1177–1183

Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, Wakefield AE (2004) Estimating the risk of nonunion following nonoperative treatment of a clavicular fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86-A:1359–1365

Faldini C, Nanni M, Leonetti D, Acri F, Galante C, Luciani D, Giannini S (2010) Nonoperative treatment of closed displaced midshaft clavicle fractures. J Orthop Traumatol: Off J Ital Soc Orthop Traumatol 11:229–236

Jones CB, Sietsema DL (2011) Analysis of operative versus nonoperative treatment of displaced scapular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469:3379–3389

Patterson JMM, Galatz L, Streubel PN, Toman J, Tornetta P, Ricci WM (2012) CT evaluation of extra-articular glenoid neck fractures: does the glenoid medialize or does the scapula lateralize? J Orthop Trauma 26:360–363

Zuckerman SL, Song YN, Obremskey WT (2012) Understanding the concept of medialization in scapula fractures. J Orthop Trauma 26:350–357

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. Terrence Endres, James Ringler, and David Bielema for the contribution of their patients and surgical skill.

Conflict of interest

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article. No funding was received for this study.

Ethical standards

Approval was granted from the Spectrum Health Institutional Review Board. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee. The need for informed consent was waived by the ethical committee since rights and interests of the patients would not be violated and their privacy and anonymity would be assured by this study design. The authors declare that this study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gilde, A.K., Hoffmann, M.F., Sietsema, D.L. et al. Functional outcomes of operative fixation of clavicle fractures in patients with floating shoulder girdle injuries. J Orthopaed Traumatol 16, 221–227 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10195-015-0349-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10195-015-0349-8